Abstract:

Background:

It has been previously demonstrated that patients with reflux esophagitis exhibit a significant impairment in the secretion of salivary protective components versus controls. However, the secretion of salivary protective factors in patients with nonerosive reflux disease (NERD) is not explored. The authors therefore studied the secretion of salivary volume, pH, bicarbonate, nonbicarbonate glycoconjugate, protein, epidermal growth factor (EGF), transforming growth factor alpha (TGF-α) and prostaglandin E2 in patients with NERD and compared with the corresponding values in controls (CTRL).

Methods:

Salivary secretion was collected during basal condition, mastication and intraesophageal mechanical (tubing, balloon) and chemical (initial saline, acid, acid/pepsin, final saline) stimulations, respectively, mimicking the natural gastroesophageal reflux.

Results:

Salivary volume, protein and TGF-α outputs in patients with NERD were significantly higher than CTRL during intraesophageal mechanical (P < 0.05) and chemical stimulations (P < 0.05). Salivary bicarbonate was significantly higher in NERD than CTRL group during intraesophageal stimulation with both acid/pepsin (P < 0.05) and saline (P < 0.01). Salivary glycoconjugate secretion was significantly higher in the NERD group than the CTRL group during chewing (P < 0.05), mechanical (P < 0.05) and chemical stimulation (P < 0.01). Salivary EGF secretion was higher in patients with NERD during mechanical stimulation (P < 0.05).

Conclusions:

Patients with NERD demonstrated a significantly stronger salivary secretory response in terms of volume, bicarbonate, glycoconjugate, protein, EGF and TGF-α than asymptomatic controls. This enhanced salivary esophagoprotection is potentially mediating resistance to the development of endoscopic mucosal changes by gastroesophageal reflux.

Key Indexing Terms: Nonerosive reflux disease, Salivary protection, Bicarbonate, Glycoconjugate, Epidermal growth factor

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a highly prevalent disease in the western world and affects approximately up to 20% of adults and nearly 25 million experience heartburn on a daily basis.1–3 Heartburn is elicited by the contact of the esophageal mucosal chemoreceptors with aggressive factors, predominantly acid, pepsin and bile components on the luminal perimeter of the esophageal mucosa during the episodes of gastroesophageal reflux.4 Response within chemoreceptors is subsequently conveyed through the afferent autonomic fibers of the esophagosalivary reflex pathway, resulting in its modulatory impact on the secretory function of salivary glands.5,6 Salivary secretion of water and inorganic components (electrolytes and buffers) is mediated predominantly by parasympathetic pathways whereas secretion of organic components (proteins, glycoconjugates and peptides) by sympathetic pathways.7–10

Salivary secretion combined with a local secretory response within the esophageal submucosal mucous glands defines the quality and the quantity of the esophageal pre-epithelial barrier, which is pivotal in the maintenance of the integrity of the esophageal epithelium.10–14 Therefore, heartburn, although often worrisome for the patient, is a beneficial symptom if it is capable of inducing an adequate salivary secretory response facilitating neutralization and inactivation of the aggressive factors within the esophageal lumen and thus restoring near-neutral pH within the esophageal lumen.12,15,16

The majority of patients with GERD (up to 60%) have no visible erosive abnormalities during standard endoscopic examination, and this subgroup is defined as nonerosive reflux disease (NERD).17,18 NERD is a condition in which typical reflux symptoms, heartburn and regurgitation are defined as troublesome in patients with negative endoscopy. The absence of visible lesions on endoscopy and the presence of troublesome reflux-associated (acidic, weakly acidic or non-acid reflux) symptoms are the 2 key factors for the definition of NERD. This clinical entity also requires abnormal impedance-pH monitoring for its diagnosis.19 It has been demonstrated previously by Rourk that patients with reflux esophagitis (RE) fail to illicit a vigorous secretory response of salivary epidermal growth factor (EGF) during intraesophageal mechanical and chemical stimulations.20 The amount of secretion of salivary protective factors in patients with NERD remains unknown. It is legitimate to surmise that a vigorous and protective salivary secretory response in terms of its major protective factors to an aggressive intraesophageal challenge in patients with NERD may prevent endoscopic mucosal injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

The study was approved by the Human Subject Committee and conducted on 33 asymptomatic volunteers (15 women and 18 men; mean age of 39 years; range, 26–56 years) and 10 white patients (4 women and 6 men; mean age of 40 years; range, 27–64 years) with a history of GERD (heartburn as a predominant symptom) confirmed by 24-hour pH monitoring and grossly normal endoscopy. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. All subjects were not afflicted with any acute illness, did not use tobacco, alcohol or chewing gum, did not receive any medications including acid suppressive therapies and antisecretory medications 14 days before the procedure, and never had any dysfunction of mastication.

Salivary Sample Collection

Subjects expectorated all saliva collected in their mouth every 10 seconds and were instructed not to swallow during the procedure. The salivary samples were sequentially collected on ice during the same time of the day for each subject as follows: (1) basal saliva during the first 10 minutes, (2) saliva produced during stimulation by parafilm chewing (mastication) during the following 5 minutes, (3) saliva produced by tubing following the placement of the intraesophageal catheter during 2 consecutive 1.5-minute intervals, (4) saliva produced following inflation of both intraesophageal balloons during 2 consecutive 1.5-minute intervals and (5) saliva produced during the esophageal perfusion with initial saline (NaCl), hydrochloric acid (HCl), HCl/pepsin and final saline consecutively, 4 samples each totaling 16 consecutive 1.5-minute intervals. The order of perfusions is very important as we go from initial saline, which represents “physiological” neutral pH reflux, followed by HCl where hydrogen ions start diffusing into the mucous barrier quickly initiating response, followed by HCl/pepsin that erodes the mucous barrier injuring the surface epithelium and finally saline, which calms down the reflux episode.

Esophageal Perfusion Catheter

Esophageal perfusion was performed with a specially designed 6-channeled catheter manufactured by Wilson-Cook Company (Chapel Hill, NC), as described in detail by Sarosiek et al.21 Four larger diameter channels were used for infusion and aspiration of the perfusate, gastric juice and incidentally swallowed saliva, which is retained above the upper balloon. Two smaller diameter channels were used for inflation of the upper and lower balloons to compartmentalize the segment of the lower esophagus.7,8,10,20–24

Perfusing Solutions

Esophageal perfusion in all subjects was performed using fresh 10 mL solutions for each 1.5-minute interval: (1) NaCl (0.15 M) that corresponds to 0.9% saline; (2) HCl (0.01 M; pH 2.1), this concentration and pH of HCl was chosen to closely resemble the content of gastroesophageal refluxate25,26; and (3) HCl (0.01 M; pH 2.1) with pepsin, where pepsin (0.5 mg/mL; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in the concentration that corresponds to the average proteolytic activity of human gastric juice.27,28

Esophageal Perfusion Procedure

Subjects were placed in the semirecumbent left-sided position. The nasopharynx was anaesthetized with xylocaine gel, the esophageal catheter was inserted into the esophagus through the nares and the balloons of the catheter were gently insufflated to seal the esophageal lumen. This procedure allows the compartmentalization of 3.75-cm segment of the esophagus between the balloons.14,21,29,30 During each perfusion period of 1.5-minute interval, the entire 10 mL solution of perfusate was circulated within the isolated segment of esophagus for a total duration of 24 minutes for each subject. The final value of each perfusion represents the mean value of 4 consecutive 1.5-minute intervals of perfusions or recirculations.

Analysis of Salivary Secretory Components

Salivary volume was assessed using a sialometer (Proflow Incorporated, Amityville, NY).8,20,22 Salivary pH was monitored using the Expandable Ion Analyzer EA 940 (Orion Res., Boston, MA).

The salivary bicarbonate and nonbicarbonate buffers were analyzed by titration and back-titration methodology using TitraLab 90 (Radiometer America Inc., Chicago, IL).31 Secretions form a thin film on the mucosa and allows the evolution of CO2 formed from acid-base interactions. Therefore, the esophageal bicarbonate buffer value would be equilibrated with CO2 tension of the lumen.31,32 This was the rationale for choosing titration to pH of 4.0 for the assessment of esophageal bicarbonate in an open system (without covering with a layer of liquid paraffin oil) with continuous CO2-free bubbling. The bicarbonate concentration was calculated using the difference in the amount of acid initially required to titrate the sample from its starting pH to pH 4.0 and the amount of base required to back-titrate the sample to its original pH after development of the CO2. The difference between the back-titration from pH 4.0 to its original starting value and the similar run of the buffer-free blank solution was used to calculate nonbicarbonate buffers.31,32 In addition, this methodology was always validated by the titration of known concentrations of bicarbonate and nonbicarbonate in the standard solutions.

Salivary glycoconjugate (predominantly mucin) was measured using the periodic–acid Schiff methodology.14,29,31 Salivary EGF was assessed by radioimmunoassay (RIA) using a commercially available kit (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL).8,20,21,31

Salivary transforming growth factor alpha (TGF-α) was recorded using a commercially available RIA kit based on highly specific sheep anti-human TGF-α antibodies (Biomedical Technologies Inc., Stoughton, MA).31,33 The separation between bound and unbound TGF-α was performed using donkey anti-sheep IgG and polyethylene glycol. Human recombinant TGF-α (BTI) was used for a standard curve. All samples were centrifuged at 4°C and 3,000 rpm for 20 minutes, which are the conditions required to spin down cellular debris, plasma membrane sheets and nuclei.

Salivary prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) was measured using an RIA kit (Amersham).30 This RIA method is based on highly specific antibodies directed to oximated form of PGE2. Salivary protein was monitored by the Lowry methodology.14

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

Data were measured as mean values of salivary collections at basal level, during parafilm chewing, following placement of tubing, following inflation of balloons and during the perfusion intervals. All results were expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis by analysis of variance was performed using Σ-Stat software (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA).

RESULTS

Salivary Inorganic Protective Components

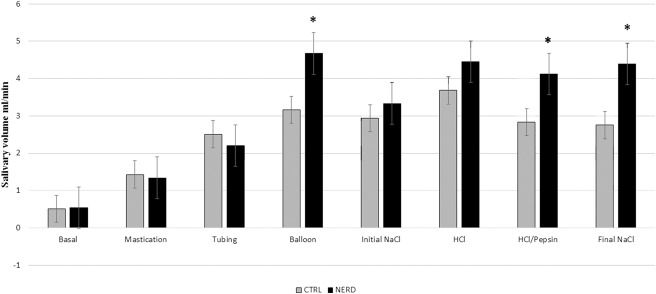

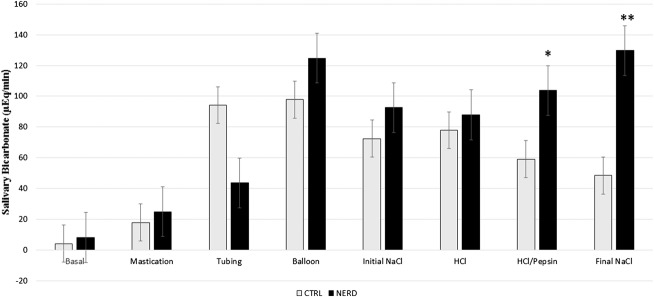

Salivary volume in patients with NERD was significantly higher than control group (CTRL) during mechanical stimulation with balloons (4.67 ± 1.16 mL/min versus 3.16 ± 0.32 mL/min, P < 0.05) and chemical stimulation with HCl/pepsin and final saline (4.12 ± 0.38 mL/min versus 2.83 ± 0.33 mL/min, P < 0.05 and 4.39 ± 0.54 mL/min versus 2.75 ± 0.33 mL/min, P < 0.05, respectively), as shown in Figure 1. The bicarbonate output in the NERD group was significantly higher than the CTRL group during chemical stimulation with HCl/pepsin (103.80 ± 15.30 μEq/min versus 59.00 ± 11.98 μEq/min, P < 0.05) and final saline (129.70 ± 25.40 μEq/min versus 48.40 ± 10.39 μEq/min, P < 0.01), as shown in Figure 2 (Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Salivary volume output in the control group (CTRL) and patients with nonerosive reflux disease (NERD) (*P < 0.05, which is significant). Salivary volume is significantly higher in patients with NERD during mechanical stimulation with balloons and chemical stimulation with HCl/pepsin (acid/pepsin) and final NaCl (final saline).

FIGURE 2.

Salivary bicarbonate output in the control group (CTRL) and patients with nonerosive reflux disease (NERD) (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, which is significant). Salivary bicarbonate secretion is significantly higher in patients with NERD during chemical stimulation with HCl/Pepsin (acid/pepsin) and final NaCl (final saline).

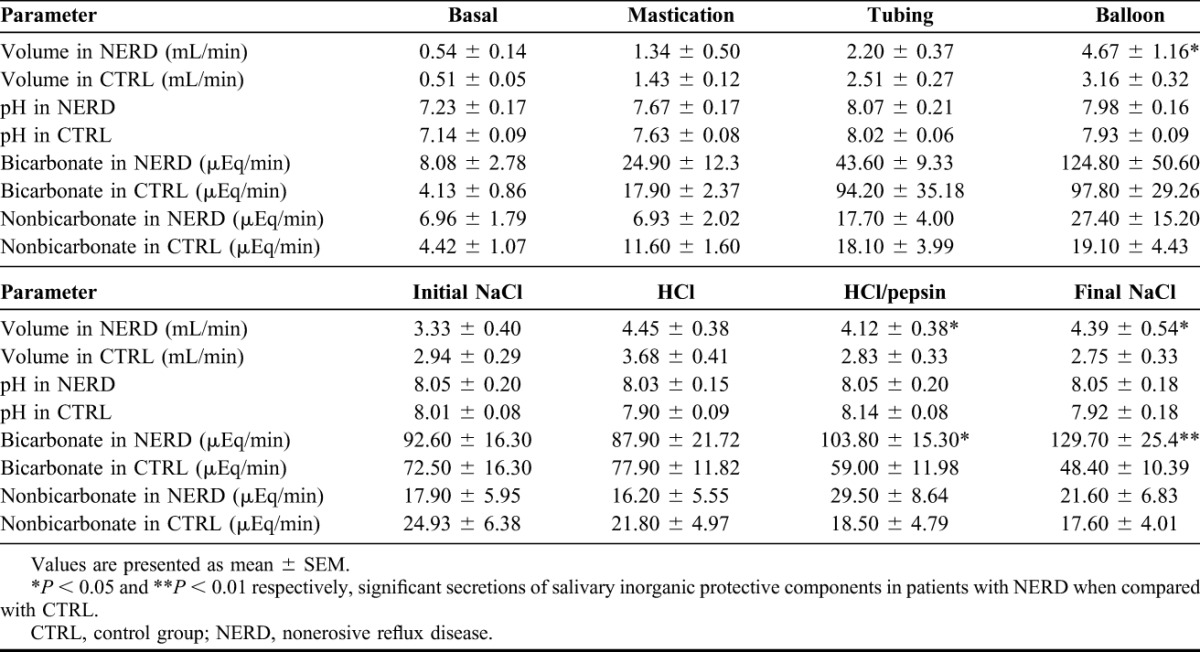

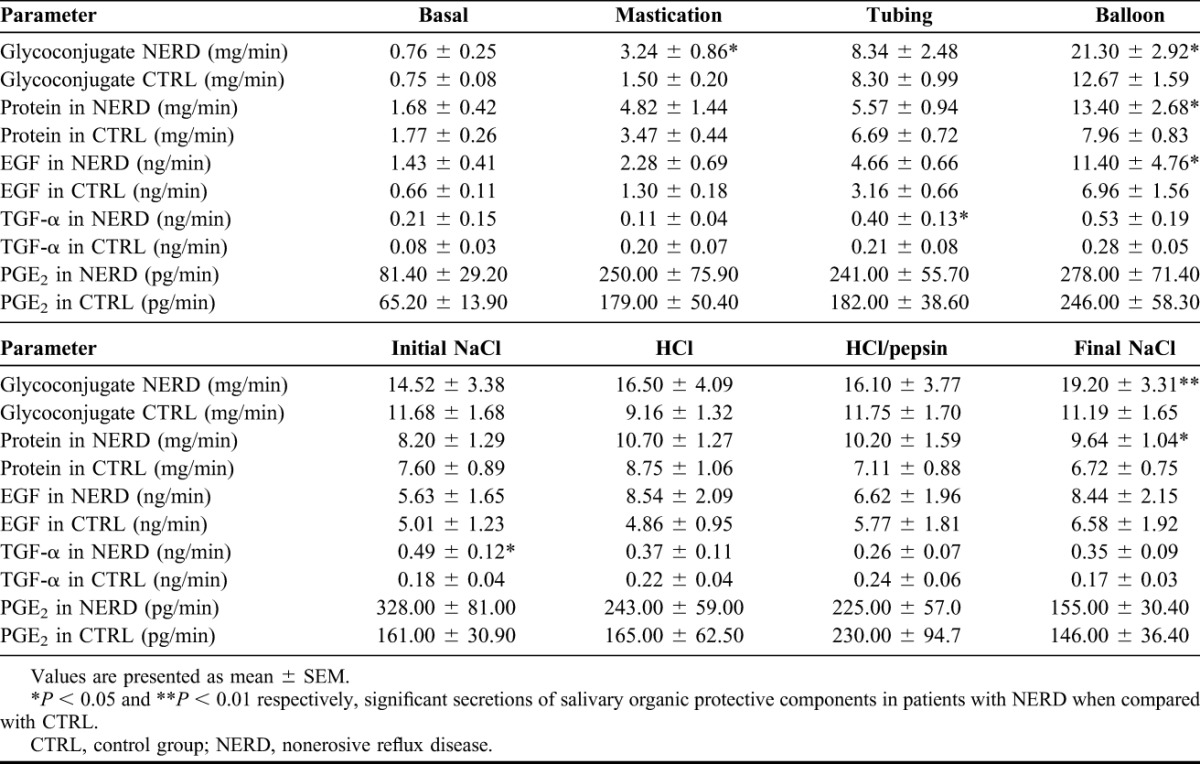

TABLE 1.

Salivary inorganic protective components in patients with NERD and CTRL (mean ± SEM)

Salivary Organic Protective Components

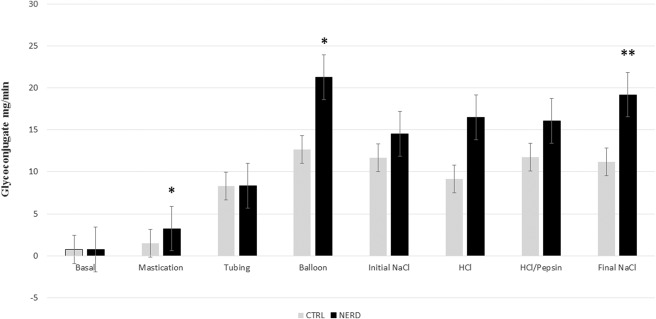

The secretion of salivary glycoconjugate was significantly higher in the NERD group than the CTRL group during mastication (3.24 ± 0.86 mg/min versus 1.50 ± 0.20 mg/min, P < 0.05), mechanical stimulation with balloons (21.30 ± 2.92 mg/min versus 12.67 ± 1.59 mg/min, P < 0.05) and during chemical stimulation with final saline (19.20 ± 3.31 mg/min versus 11.19 ± 1.65 mg/min, P < 0.01), as shown in Figure 3. Mechanical stimulation with balloons significantly increased protein output in the NERD when compared with the CTRL (13.40 ± 2.68 mg/min versus 7.96 ± 0.83 mg/min, P < 0.05). A similar phenomenon was revealed during the chemical stimulation with final saline (9.64 ± 1.04 mg/min versus 6.72 ± 0.75 mg/min, P < 0.05) (Table 2).

FIGURE 3.

Salivary glycoconjugate output in the control group (CTRL) and patients with nonerosive reflux disease (NERD) (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, which is significant). Salivary glycoconjugate secretion is significantly higher in patients with NERD during mastication, mechanical stimulation with balloons and chemical stimulation with final NaCl (final saline).

TABLE 2.

Salivary organic protective components in patients with NERD and CTRL

The salivary secretion of EGF in patients with NERD was significantly higher than controls during mechanical stimulation with balloons (11.40 ± 4.76 ng/min versus 6.96 ± 1.56 ng/min, P < 0.05). We observed higher TGF-α output in the NERD than the CTRL group during mechanical stimulation with tubing (0.40 ± 0.13 ng/min versus 0.21 ± 0.08 ng/min, P < 0.05) and chemical stimulation with initial saline (0.49 ± 0.12 ng/min versus 0.18 ± 0.04 ng/min, P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

NERD is a distinct pattern of GERD characterized by reflux-related symptoms in the absence of esophageal mucosal erosions/breaks at conventional endoscopy.34 Patients with NERD can be subdivided as follows based on etiology: (1) NERD pH-positive patients with normal endoscopy and abnormal distal esophageal acid exposure, (2) NERD patients with hypersensitive esophagus with normal endoscopy, normal distal esophageal acid exposure and positive symptom association for either acid (acid hypersensitive esophagus) or non-acid reflux (non-acid hypersensitive esophagus) and (3) patients with functional heart burn patients.35 The pathogenesis of NERD includes microscopic inflammation, visceral hypersensitivity and sustained esophageal contractions. It has been observed that acid exposure disrupts intracellular connections in esophageal mucosa, producing dilated intercellular spaces and increasing esophageal permeability, allowing refluxed acid to penetrate the submucosa and reach chemosensitive nociceptors causing symptoms. Peripheral receptors are shown to be mediating esophageal hypersensitivity because of acid reflux including upregulation of acid sensing ion channels.34

The integrity of the esophageal mucosa depends on an equilibrium between aggressive factors (acid, pepsin and bile components) and defense mechanisms.7,12,14,16,20,23,29,33,36 Esophageal mucosal defense mechanisms operate as 3 complementary barriers: pre-epithelial, epithelial and post-epithelial.10,12,36 It has been demonstrated recently that salivary bicarbonate secretion is significantly higher up to 3-folds when the upper esophageal mucosa was exposed to acid and pepsin, leading to its better protection when compared with salivary secretory response during exposure to acid and pepsin of lower esophageal mucosa.36 Marcinkiewicz et al31 previously demonstrated an increase in esophageal mucosal secretory protective factors in patients with NERD. This study focuses on the salivary secretory components of the pre-epithelial barrier in patients with NERD as a vanguard of mucosal protection.

Current insight shows that the secretion of salivary protective components may be important in prevention of the development of endoscopic mucosal damage. Salivary volume dilutes intraluminal acid and pepsin originating from the gastroesophageal refluxate.17 Glycoconjugate has a protective role by retarding hydrogen ion diffusion through and to provide an architectural framework for the unstirred layer of the mucus bicarbonate barrier.19,37 The EGF and TGF-α bind to the same receptor located on the apical domain of esophageal squamous epithelium, participating in the proliferation and differentiation of the esophageal epithelium.38 EGF is also related to esophageal and gastric mucosal repair of the alimentary tract injury.11

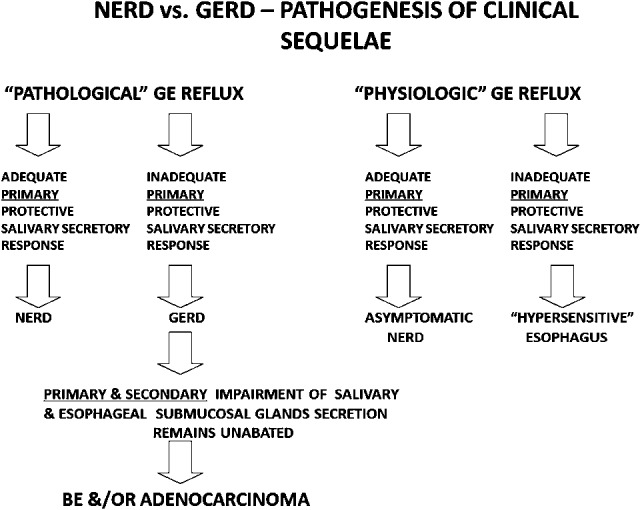

It was demonstrated by Rourk et al20 that patients with RE exhibited a significant impairment not only in the secretion of salivary EGF but also esophageal EGF.39 Namiot et al29 also demonstrated a decline in esophageal mucin secretion in patients with RE. The esophageal mucosal protection is contributed by 2 factors: (1) the secretion of salivary protective factors by salivary glands that flows through esophagus and (2) the local secretion of protective factors by submucosal mucous glands of esophagus itself. Patients with NERD were found to have strong secretions of salivary protective factors demonstrated by this study as well as esophageal protective factors studied previously by Marcinkiewicz et al.31 This double protection in patients with NERD might prevent or delay the progression to Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma (Figure 4). The simple way to help patients is to achieve stronger salivary secretion by chewing a sugarless gum through masticatory stimulation, which suggests its potential value as a therapeutic approach to the treatment of patients with GERD.23

FIGURE 4.

Nonerosive reflux disease (NERD) versus gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): pathogenesis of clinical sequelae. Despite pathological gastroesophageal (GE) reflux, patients with NERD are protected against mucosal erosive lesions, Barrett's esophagus (BE) and/or esophageal adenocarcinoma because of adequate stronger primary salivary protective components.

As per this study, patients with NERD demonstrated an increase in salivary volume during mechanical and chemical stimulations and bicarbonate during chemical stimulation, mediated by vagovagal neural reflex so-called esophagosalivary reflex. This stronger salivary flow might potentially neutralize acid/pepsin, providing protection. Patients with NERD also showed higher secretions of salivary glycoconjugates (mucin), protein and TGF-α during intraesophageal mechanical and chemical stimulation than controls. It was also found that EGF output during intraesophageal mechanical stimulation by balloons was more than 60% higher in patients with NERD than controls. An important point to note in the current data analysis was that both NERD and CTRL groups showed an increase in the secretions of salivary components during mechanical and chemical stimulations from baseline, but salivary secretions were significantly higher in patients with NERD than controls. Current data provided new evidence that significantly higher secretions of inorganic and organic salivary protective components might quantitatively and qualitatively enhance the protective potential of the mucus/bicarbonate layer covering the esophageal mucosa in patients with NERD.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients with NERD demonstrated a significantly stronger salivary secretory response in terms of volume, bicarbonate, glycoconjugate, protein, EGF and TGF-α than asymptomatic controls. This enhanced salivary esophagoprotection is potentially mediating resistance to the development of endoscopic mucosal changes by gastroesophageal reflux.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank Dr. R. W. McCallum for his support and encouragement.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Camilleri M, Dubois D, Coulie B, et al. Prevalence and socioeconomic impact of upper gastrointestinal disorders in the United States: results of the US Upper Gastrointestinal Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;3:543–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, et al. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut 2005;54:710–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toghanian S, Wahlqvist P, Johnson DA, et al. The burden of disrupting gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a database study in US and European cohorts. Clin Drug Investig 2010;30:167–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mattox HE, III, Richter JE. Prolonged ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring in the evaluation of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Med 1990;89:345–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hightower NC. Salivary secretion. In: Best CH, Taylor NB, editors. The Physiological Basis of Medical Practice. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins Co; 1966. p. 1061–80. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kay RN, Phillipson AT. Responses of the salivary glands to distension of the oesophagus and rumen. J Physiol 1959;148:507–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Namiot Z, Rourk RM, Piascik R, et al. Interrelationship between esophageal challenge with mechanical and chemical stimuli and salivary protective mechanisms. Am J Gastroenterol 1994;89:581–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li L, Yu Z, Piascik R, et al. Effect of esophageal intraluminal mechanical and chemical stressors on salivary epidermal growth factor in humans. Am J Gastroenterol 1993;88:1749–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Namiot Z, Yu ZJ, Piascik R, et al. Modulatory effect of esophageal intraluminal mechanical and chemical stressors on salivary prostaglandin E2 in humans. Am J Med Sci 1997;313:90–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarosiek J, McCallum RW. What role do salivary inorganic components play in health and disease of the esophageal mucosa? Digestion 1995;56(suppl 1):24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarosiek J, Feng T, McCallum RW. The interrelationship between salivary epidermal growth factor and the functional integrity of the esophageal mucosal barrier in the rat. Am J Med Sci 1991;302:359–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarosiek J, McCallum RW. The evolving appreciation of the role of esophageal mucosal protection in the pathophysiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Pract Gastroenterol 1994;18:20J–Q. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarosiek J, Namiot Z, Piascik R, et al. What part do the mucous cells of submucosal mucous glands play in the esophageal pre-epithelial barrier? In: Giuli R, Tytgat GNJ, DeMeester TR, et al., editors. The Esophageal Mucosa. Amsterdam, Lausanne, New York, Oxford, Shannon, Tokyo: Elsevier; 1994. p. 278–90. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Namiot Z, Sarosiek J, Rourk RM, et al. Human esophageal secretion: mucosal response to luminal acid and pepsin. Gastroenterology 1994;106:973–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith JL, Opekun AR, Larkai E, et al. Sensitivity of the esophageal mucosa to pH in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 1989;96:683–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helm JF, Dodds WJ, Pelc LR, et al. Effect of esophageal emptying and saliva on clearance of acid from the esophagus. N Engl J Med 1984;310:284–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zagari RM, Fuccio L, Wallander MA, et al. Gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms, oesophagitis and Barrett's oesophagus in the general population: the Loiano-Monghidoro study. Gut 2008;57:1354–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ronkainen J, Aro P, Storskrubb T, et al. High prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and esophagitis with or without symptoms in the general adult Swedish population: a Kalixanda study report. Scand J Gastroenterol 2005;40:275–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slomiany BL, Sarosiek J, Slomiany A. Gastric mucus and the mucosal barrier. Dig Dis 1987;5:125–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rourk RM, Namiot Z, Sarosiek J, et al. Impairment of salivary epidermal growth factor secretory response to esophageal mechanical and chemical stimulation in patients with reflux esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1994;89:237–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarosiek J, Hetzel DP, Yu Z, et al. Evidence on secretion of epidermal growth factor by the esophageal mucosa in humans. Am J Gastroenterol 1993;88:1081–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarosiek J, Rourk RM, Piascik R, et al. The effect of esophageal mechanical and chemical stimuli on salivary mucin secretion in healthy individuals. Am J Med Sci 1994;308:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarosiek J, Scheurich CJ, Marcinkiewicz M, et al. Enhancement of salivary esophagoprotection: rationale for a physiological approach to gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 1996;110:675–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldin GF, Marcinkiewicz M, Zbroch T, et al. Esophagoprotective potential of cisapride. An additional benefit for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci 1997;42:1362–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson LF. Historical perspectives on esophageal pH monitoring. In: Richter JE, editor. Ambulatory Esophageal pH Monitoring. New York, NY: Igaku-Shoin; 1991. p. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demeester TR, Johnson LF, Joseph GJ, et al. Patterns of gastroesophageal reflux in health and disease. Ann Surg 1976;184:459–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirschowitz BI. A critical analysis, with appropriate controls, of gastric acid and pepsin secretion in clinical esophagitis. Gastroenterology 1991;101:1149–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker V, Taylor WH. Pepsin 1 secretion in chronic peptic ulceration. Gut 1980;21:766–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Namiot Z, Sarosiek J, Marcinkiewicz M, et al. Declined human esophageal mucin secretion in patients with severe reflux esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci 1994;39:2523–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarosiek J, Yu Z, Namiot Z, et al. Impact of acid and pepsin on human esophageal prostaglandins. Am J Gastroenterol 1994;89:588–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marcinkiewicz M, Han K, Zbroch T, et al. The potential role of the esophageal pre-epithelial barrier components in the maintenance of integrity of the esophageal mucosa in patients with endoscopically negative gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:1652–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Izutsu KT. Theory and measurement of the buffer value of bicarbonate in saliva. J Theor Biol 1981;90:397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marcinkiewicz M, Namiot Z, Edmunds MC, et al. Detrimental impact of acid and pepsin on the rate of luminal release of transforming growth factor alpha. Its potential pathogenetic role in the development of reflux esophagitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 1996;23:261–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen CL, Hsu PI. Current advances in the diagnosis and treatment of nonerosive reflux disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2013;2013:653989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giacchino M, Savarino V, Savarino E. Distinction between patients with non-erosive reflux disease and functional heartburn. Ann Gastroenterol 2013;26:283–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skoczylas T, Yandrapu H, Poplawski C, et al. Salivary bicarbonate as a major factor in the prevention of upper esophageal mucosal injury in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci 2014;59:2411–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarosiek J, Slomiany A, Slomiany BL. Retardation of hydrogen ion diffusion by gastric mucus constituents: effect of proteolysis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1983;115:1053–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jankowski J, Murphy S, Coghill G, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptors in the oesophagus. Gut 1992;33:439–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rourk RM, Namiot Z, Edmunds MC, et al. Diminished luminal release of esophageal epidermal growth factor in patients with reflux esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1994;89:1177–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]