Abstract

BACKGROUND

Enzalutamide is an oral androgen-receptor inhibitor that prolongs survival in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer in whom the disease has progressed after chemotherapy. New treatment options are needed for patients with metastatic prostate cancer who have not received chemotherapy, in whom the disease has progressed despite androgen-deprivation therapy.

METHODS

In this double-blind, phase 3 study, we randomly assigned 1717 patients to receive either enzalutamide (at a dose of 160 mg) or placebo once daily. The coprimary end points were radiographic progression-free survival and overall survival.

RESULTS

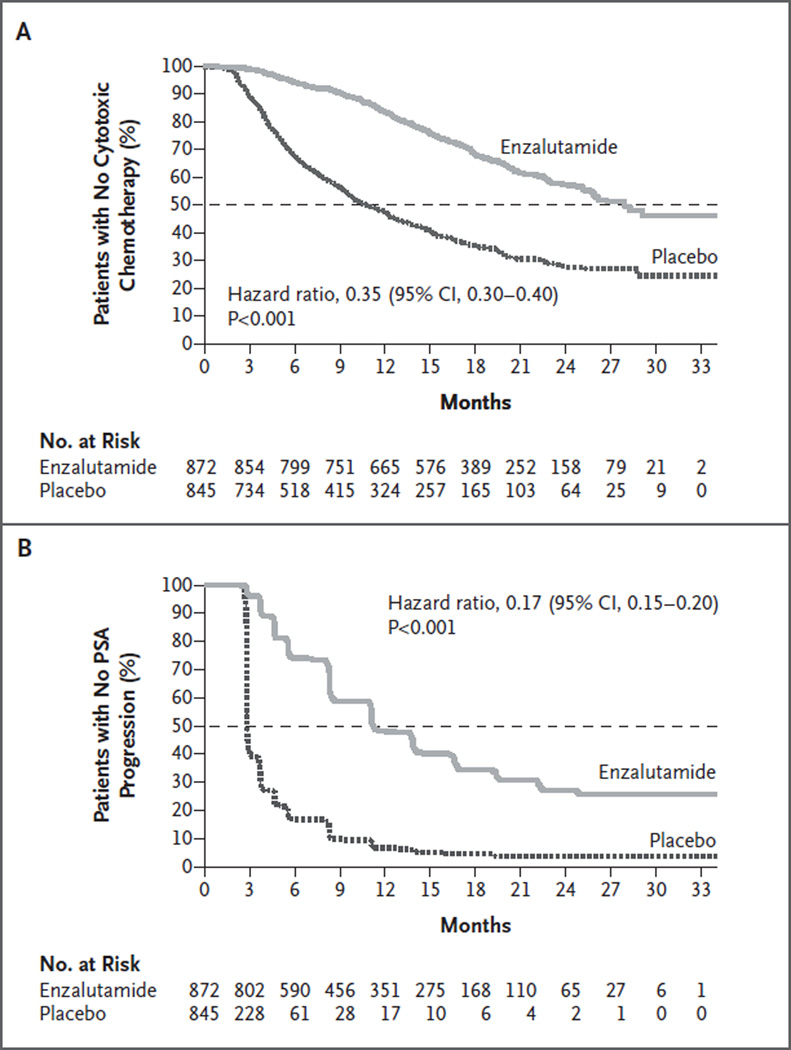

The study was stopped after a planned interim analysis, conducted when 540 deaths had been reported, showed a benefit of the active treatment. The rate of radiographic progression-free survival at 12 months was 65% among patients treated with enzalutamide, as compared with 14% among patients receiving placebo (81% risk reduction; hazard ratio in the enzalutamide group, 0.19; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.15 to 0.23; P<0.001). A total of 626 patients (72%) in the enzalutamide group, as compared with 532 patients (63%) in the placebo group, were alive at the data-cutoff date (29% reduction in the risk of death; hazard ratio, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.60 to 0.84; P<0.001). The benefit of enzalutamide was shown with respect to all secondary end points, including the time until the initiation of cytotoxic chemotherapy (hazard ratio, 0.35), the time until the first skeletal-related event (hazard ratio, 0.72), a complete or partial soft-tissue response (59% vs. 5%), the time until prostate-specific antigen (PSA) progression (hazard ratio, 0.17), and a rate of decline of at least 50% in PSA (78% vs. 3%) (P<0.001 for all comparisons). Fatigue and hypertension were the most common clinically relevant adverse events associated with enzalutamide treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

Enzalutamide significantly decreased the risk of radiographic progression and death and delayed the initiation of chemotherapy in men with metastatic prostate cancer. (Funded by Medivation and Astellas Pharma; PREVAIL ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01212991.)

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the sixth leading cause of cancer-related death among men worldwide.1 Strategies to block androgen-receptor signaling have formed the backbone of prostate-cancer therapy since the first description of the hormonal dependence of this cancer in 1941.2 Advances in endocrine therapies have improved survival in men with high-risk locoregional prostate cancer.3,4 However, new hormonal agents have been shown to extend survival in men with metastatic castration-resistant disease.5–9

In most patients who are treated for advanced recurrent prostate cancer with androgen-deprivation therapy (comprising a luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone [LHRH] analogue or orchiectomy with or without an antiandrogen), disease progression occurs despite effective suppression of serum testosterone. This disease state, called castration-resistant prostate cancer, is almost always associated with increases in levels of serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA), suggesting that the disease continues to be driven by androgen- receptor signaling. Preclinical evidence suggests that androgen-receptor overexpression is sufficient to confer resistance to androgen deprivation in prostate-cancer cell lines10,11 and that levels of intratumoral androgens are often increased in patients with progressive prostate cancer.12 These observations have provided a clear basis for developing more effective methods to treat prostate cancer by further suppressing androgen-receptor signaling.13,14

Enzalutamide (formerly known as MDV3100) is a rationally designed, targeted androgen-receptor inhibitor that competitively binds to the ligand-binding domain of the androgen receptor and inhibits androgen-receptor translocation to the cell nucleus, recruitment of androgen-receptor cofactors, and androgen-receptor binding to DNA.15 In a phase 1–2 trial, enzalutamide was found to have encouraging antitumor activity in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer, with data suggesting a greater benefit in men who had not yet received chemotherapy.16 In a previous phase 3 study, enzalutamide, as compared with placebo, prolonged overall and progression-free survival, improved patient-reported quality of life, and delayed the development of skeletal-related complications in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer who had previously received docetaxel.7 In our study, we evaluated enzalutamide in men in whom hormonal agents are frequently administered (i.e., those who have asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic metastatic disease that has progressed despite the use of androgen-deprivation therapy) and who have not undergone chemotherapy.

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN AND CONDUCT

The PREVAIL study was a multinational, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial of enzalutamide. The study was approved by the independent review board at each participating site and was conducted according to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice Guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonisation. All patients provided written informed consent before participating in the trial. An independent data and safety monitoring committee reviewed safety data at regular intervals and reviewed the prespecified interim analysis conducted by an independent statistical group at the contract clinical research organization where the study database was held.

The study was designed by prostate-cancer experts and employees of the sponsors, Medivation and Astellas Pharma, which are codeveloping enzalutamide. Investigators at the participating centers entered the data into an electronic data-capture system that was verified for source data by monitors from a separate clinical research organization. The data analyses reported here were conducted by the sponsor and were provided to all the authors, who wrote the manuscript and made the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. These authors assume responsibility for the accuracy of the data and adherence to the study protocol, which is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org. A professional writer who was paid by the sponsors assisted in the preparation of the manuscript. All the authors and participating institutions have agreements with the sponsors regarding the confidentiality of the data.

STUDY PARTICIPANTS

Patients were eligible if they had histologically or cytologically confirmed adenocarcinoma of the prostate with documented metastases and had PSA progression, radiographic progression, or both in bone or soft tissue, despite receiving LHRH analogue therapy or undergoing orchiectomy, with a serum testosterone level of 1.73 nmol per liter (50 ng per deciliter) or less. Continued androgen-deprivation therapy was required. Previous antiandrogen therapy and concurrent use of glucocorticoids were permitted but not required. Eligible patients had not received cytotoxic chemotherapy, ketoconazole, or abiraterone acetate, had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status grade of 0 or 1 (no symptoms or ambulatory but restricted in strenuous activities), and were either asymptomatic (score of 0 to 1) or mildly symptomatic (score of 2 to 3), as measured on the Brief Pain Inventory Short Form question 3 (on which scores range from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating a greater severity of pain). Patients with visceral disease, including lung or liver metastases, were eligible, as were patients with New York Heart Association class I or II heart failure. Patients with a history of seizure or a condition that could confer a predisposition to seizure were excluded, although patients taking medications associated with lowering the seizure threshold were eligible.

From September 2010 through September 2012, patients were enrolled at 207 sites globally. All patients were randomly assigned to receive either oral enzalutamide (at a dose of 160 mg) or placebo once daily with or without food. Randomization was stratified according to the study site. Treatment continued until the occurrence of unacceptable side effects or confirmed radiographic progression and the initiation of chemotherapy or an investigational agent. Treatment discontinuation because of an increase in the PSA level alone was discouraged.

STUDY END POINTS

Coprimary end points were radiographic progression-free survival and overall survival. Secondary end points included the time until the initiation of cytotoxic chemotherapy, the time until the first skeletal-related event, the best overall soft-tissue response, the time until PSA progression, and a decline in the PSA level of 50% or more from baseline. Prespecified exploratory end points included quality of life, as measured with the use of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Prostate (FACT-P) scale, and a decline in the PSA level of 90% or more from baseline. End-point definitions are provided in Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org.

Radiographic disease was evaluated with the use of either computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging and with the use of bone scanning. Imaging was performed at the time of screening, at weeks 9, 17, and 25, and every 12 weeks thereafter. Radiologists at a central location who were unaware of the study-group assignments determined whether there was progressive disease on the basis of Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), version 1.1, for soft tissue or on the basis of criteria adapted from the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group 217 for osseous disease (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The planned enrollment was approximately 1680 patients. The coprimary end points were analyzed in the intention-to-treat population at a total type I error rate of 0.05, with an error rate of 0.001 (two-sided) allocated to radiographic progression-free survival and an error rate of 0.049 (two-sided) allocated to overall survival. It was planned that the final analysis of radiographic progression-free survival would be conducted after the occurrence of at least 410 events at the time of the interim analysis of overall survival. The interim analysis of overall survival was to be conducted after the occurrence of approximately 516 deaths, or 67% of the 765 deaths specified for the final analysis. The final analysis of radiographic progression-free survival was performed after the occurrence of 439 events (with data cutoff on May 6, 2012); the interim analysis of overall survival was performed after the occurrence of 540 deaths with the use of a two-sided type I error rate of 0.0147. Holm’s step-down procedure was applied to the analyses of the secondary end points to maintain a two-sided type I error of 5%.18 The results presented here are based on a cutoff date of September 16, 2013, unless otherwise specified. An updated survival analysis was performed with a data-cutoff date of January 15, 2014.

RESULTS

STUDY PATIENTS

A total of 1717 patients were enrolled in the study, with 872 in the enzalutamide group and 845 in the placebo group; 1715 patients received at least one dose of a study drug (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). Baseline demographic and disease characteristics were well balanced between the two groups (Tables S2 and S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). The median time that patients received a study drug was substantially longer in the enzalutamide group than in the placebo group (16.6 months vs. 4.6 months). More patients in the enzalutamide group than in the placebo group received at least 12 months of treatment (68% vs. 18%) and continued to receive treatment as of the data-cutoff date (42% vs. 7%).

COPRIMARY END POINTS

Radiographic Progression-free Survival

At 12 months of follow-up, the rate of radiographic progression-free survival was 65% in the enzalutamide group and 14% in the placebo group. Treatment with enzalutamide, as compared with placebo, resulted in an 81% reduction in the risk of radiographic progression or death (hazard ratio in the enzalutamide group, 0.19; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.15 to 0.23; P<0.001) (Fig. 1A). Fewer patients in the enzalutamide group than in the placebo group had radiographic progression or died (118 of 832 patients [14%] vs. 321 of 801 patients [40%]). The median radiographic progression-free survival was not reached in the enzalutamide group, as compared with 3.9 months in the placebo group. The treatment effect of enzalutamide on radiographic progression-free survival was consistent across all prespecified subgroups (Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Figure 1. Kaplan–Meier Estimates of Radiographic Progression-free Survival and Overall Survival.

Shown are data for the coprimary end points of radiographic progression-free survival (Panel A) and overall survival (Panel B). The dashed horizontal lines indicate medians. Hazard ratios are based on unstratified Cox regression models with treatment as the only covariate, with values of less than 1.00 favoring enzalutamide.

Overall Survival

At the planned interim analysis of overall survival, the median duration of follow-up for survival was approximately 22 months. Fewer deaths occurred in the enzalutamide group than in the placebo group (241 of 872 patients [28%] vs. 299 of 845 patients [35%]). Treatment with enzalutamide, as compared with placebo, resulted in a 29% decrease in the risk of death (hazard ratio, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.60 to 0.84; P<0.001) (Fig. 1B). The median overall survival was estimated at 32.4 months in the enzalutamide group and 30.2 months in the placebo group. The treatment effect of enzalutamide on overall survival was consistent across all prespecified subgroups (Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). The risk reductions for both coprimary end points were unaffected by previous exposure to antiandrogens. After review of the interim coprimary efficacy and safety results, the data and safety monitoring committee recommended halting the study and offering enzalutamide to eligible patients receiving placebo. An updated analysis of overall survival with 116 additional deaths showed that 82% of patients in the enzalutamide group and 73% of those in the placebo group were alive at 18 months; the estimated median was not yet reached in the enzalutamide group and was 31.0 months in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.63 to 0.85; P<0.001) (Table S4 in the Supplementary Appendix).

SUBSEQUENT ANTINEOPLASTIC THERAPY

Subsequent antineoplastic treatments associated with a demonstrated survival benefit in metastatic prostate cancer were received by 40% of patients in the enzalutamide group, as compared with 70% of those in the placebo group. The two most common subsequent therapies were docetaxel (received by 33% and 57% of patients, respectively) and abiraterone (received by 21% and 46%, respectively) (Table S5 in the Supplementary Appendix). The use of abiraterone was more common in North America than in other regions. The duration and efficacy of post-progression therapies were not ascertained.

PRESPECIFIED SECONDARY AND EXPLORATORY END POINTS

The superiority of enzalutamide over placebo was shown with respect to all secondary end points. The median time until the initiation of cytotoxic chemotherapy was 28.0 months in the enzalutamide group, as compared with 10.8 months in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.35; P<0.001) (Table 1 and Fig. 2A). Treatment with enzalutamide also resulted in a reduction in the risk of a first skeletal-related event, which occurred in 278 patients (32%) in the enzalutamide group and 309 patients (37%) in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.72; P<0.001) at a median of approximately 31 months in each of the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Secondary and Prespecified Exploratory End Points.*

| End Point | Enzalutamide (N = 872) |

Placebo (N = 845) |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median time until initiation of cytotoxic chemotherapy — mo | 28.0 | 10.8 | 0.35 (0.30–0.40) | <0.001 |

| Median time until decline in the FACT-P global score — mo†‡ | 11.3 | 5.6 | 0.63 (0.54–0.72) | <0.001 |

| Median time until first skeletal-related event — mo§ | 31.1 | 31.3 | 0.72 (0.61–0.84) | <0.001 |

| Median time until PSA progression — mo¶ | 11.2 | 2.8 | 0.17 (0.15–0.20) | <0.001 |

| Confirmed change in PSA‖ | ||||

| Patients with ≥1 post-baseline PSA assessment — no. (%) | 854 (98) | 777 (92) | ||

| PSA decline of ≥50% from baseline — no./total no. (%) | 666/854 (78) | 27/777 (3) | <0.001 | |

| PSA decline of ≥90% from baseline — no./total no. (%)† | 400/854 (47) | 9/777 (1) | <0.001 | |

| Patients with measurable soft-tissue disease — no. (%)** | 396 (45) | 381 (45) | ||

| Objective response | 233 (59) | 19 (5) | <0.001 | |

| Complete response | 78 (20) | 4 (1) | ||

| Partial response | 155 (39) | 15 (4) |

A complete definition of study end points is provided in Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix. CI denotes confidence interval, and PSA prostate-specific antigen.

This category was a prespecified exploratory end point.

A decline on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Prostate (FACT-P) scale was defined as decrease of 10 points or more on the global score, which ranges from 0 to 156, with higher scores indicating a better quality of life.

The hazard ratio is a more accurate measure of treatment effect than are estimates of the median time until the event for late-occurring events in this study.

PSA progression was based on criteria of the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group 2.

Only patients with baseline and post-baseline assessments are included.

Only patients with measurable soft-tissue disease at baseline, as assessed on the basis of the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.1, are included.

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier Estimates for the Times until the Initiation of Cytotoxic Chemotherapy and an Increased Level of Prostate-Specific Antigen.

Shown are secondary efficacy end points that include the time until the initiation of cytotoxic chemotherapy (Panel A) and the time until an increased level of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) (Panel B). The horizontal dashed lines indicate medians. Hazard ratios are based on unstratified Cox regression models with treatment as the only covariate, with values of less than 1.00 favoring enzalutamide. The full definition of PSA progression is provided in Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix.

Among patients with measurable soft-tissue disease at baseline, 59% of the patients in the enzalutamide group, as compared with 5% in the placebo group, had an objective response (P<0.001) (Table 1): complete and partial responses were observed in 20% and 39% of the patients, respectively, in the enzalutamide group, as compared with 1% and 4%, respectively, in the placebo group. Enzalutamide was also superior to placebo with respect to reductions of at least 50% and 90% in the PSA level, the time until PSA progression, and the time until a decline in the quality of life (Table 1 and Fig. 2B). The median time until a quality-of-life deterioration, as measured on the FACT-P scale, was 11.3 months in the enzalutamide group and 5.6 months in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.63; P<0.001).

SAFETY

Adverse events are summarized in Tables 2 and 3 (with events occurring in at least 10% of patients in the enzalutamide group listed in the latter table). The median reporting period for adverse events was 17.1 months in the enzalutamide group and 5.4 months in placebo group, which reflected the longer exposure of patients to enzalutamide. A grade 3 or higher adverse event was reported in 43% of the patients in the enzalutamide group, as compared with 37% in the placebo group; however, the median time until the first event of grade 3 or higher was 22.3 months in the enzalutamide group and 13.3 months in the placebo group (Fig. S4 in the Supplementary Appendix). The most common adverse events leading to death were disease progression and a general deterioration in physical health, with similar incidences in the two groups.

Table 2.

Summary of Adverse Events.

| Variable | Enzalutamide (N = 871) |

Placebo (N = 844) |

|---|---|---|

| Median safety reporting period — mo | 17.1 | 5.4 |

| Any adverse event — no. (%) | 844 (97) | 787 (93) |

| Any grade ≥3 adverse event — no. (%) | 374 (43) | 313 (37) |

| Median time until first grade ≥3 adverse event — mo | 22.3 | 13.3 |

| Any serious adverse event — no. (%) | 279 (32) | 226 (27) |

| Any adverse event leading to treatment discontinuation — no. (%) | 49 (6) | 51 (6) |

| Any adverse event leading to death — no. (%) | 37 (4) | 32 (4) |

Table 3.

Most Common Adverse Events and Events of Special Interest.

| Adverse Events | Enzalutamide (N = 871) |

Placebo (N = 844) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Grades | Grade ≥3 | All Grades | Grade ≥3 | |

| number of patients (percent) | ||||

| Most common adverse events* | ||||

| Fatigue | 310 (36) | 16 (2) | 218 (26) | 16 (2) |

| Back pain | 235 (27) | 22 (3) | 187 (22) | 25 (3) |

| Constipation | 193 (22) | 4 (<1) | 145 (17) | 3 (<1) |

| Arthralgia | 177 (20) | 12 (1) | 135 (16) | 9 (1) |

| Decreased appetite | 158 (18) | 2 (<1) | 136 (16) | 6 (1) |

| Hot flush | 157 (18) | 1 (<1) | 65 (8) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 142 (16) | 2 (<1) | 119 (14) | 3 (<1) |

| Hypertension | 117 (13) | 59 (7) | 35 (4) | 19 (2) |

| Asthenia | 113 (13) | 11 (1) | 67 (8) | 8 (1) |

| Fall | 101 (12) | 12 (1) | 45 (5) | 6 (1) |

| Weight loss | 100 (11) | 5 (1) | 71 (8) | 2 (<1) |

| Edema peripheral | 92 (11) | 2 (<1) | 69 (8) | 3 (<1) |

| Headache | 91 (10) | 2 (<1) | 59 (7) | 3 (<1) |

| Specific adverse events | ||||

| Any cardiac adverse event | 88 (10) | 24 (3) | 66 (8) | 18 (2) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 16 (2) | 3 (<1) | 12 (1) | 5 (1) |

| Acute coronary syndromes | 7 (1) | 7 (1) | 4 (<1) | 2 (<1) |

| Acute renal failure | 32 (4) | 12 (1) | 38 (5) | 12 (1) |

| Ischemic or hemorrhagic cerebrovascular event | 12 (1) | 6 (1) | 9 (1) | 3 (<1) |

| Elevation in alanine aminotransferase level | 8 (1) | 2 (<1) | 5 (1) | 1 (<1) |

| Seizure | 1 (<1)† | 1 (<1)† | 1 (<1) | 0 |

Included in this category are adverse events that were reported in at least 10% of patients in the enzalutamide group at a rate that was at least 2 percentage points higher than that in the placebo group.

This seizure occurred after the data-cutoff date.

Adverse events that occurred in 20% or more of patients receiving enzalutamide at a rate that was at least 2 percentage points higher than that in the placebo group were fatigue (Table S6 in the Supplementary Appendix), back pain, constipation, and arthralgia. After adjustment for the length of exposure, events with a higher rate in the enzalutamide group than in the placebo group were hot flush (14 vs. 12 events per 100 patient-years), hypertension (11 vs. 7 events per 100 patient-years), and falls (11 vs. 9 events per 100 patient-years). The most common event of grade 3 or higher in the enzalutamide group was hypertension, which was reported in 7% of the patients. The most common cardiac event was atrial fibrillation, which was reported in 2% of the patients in the enzalutamide group and in 1% of those in the placebo group. One patient in each study group had a seizure. No evidence of hepatotoxicity, as measured by adverse events or laboratory assessments, was observed in the enzalutamide group.

DISCUSSION

In our study involving men with metastatic prostate cancer who had not received previous chemotherapy, enzalutamide extended the time until radiographic progression or death, improved overall survival, and delayed the initiation of chemotherapy by a median of 17 months. The benefit of enzalutamide on radiographic progression-free survival was observed from the first assessment 2 months after randomization and conferred a relative reduction of 81% in the risk of progression or death. Consistent benefit was observed in all prespecified subgroups, including patients with visceral disease, a population with a poorer prognosis that has been excluded from other trials involving men with metastatic prostate cancer who have not received previous chemotherapy.8,19

Enzalutamide significantly reduced the risk of death by 29% over placebo, even though patients in the placebo group had received effective post-progression therapy more frequently and earlier than those in the enzalutamide group. The benefit of enzalutamide was observed as early as 4 months after randomization and was maintained throughout the study, as depicted by the separation in the Kaplan–Meier survival curves (Fig. 1B). At the time the trial was halted, following the interim analysis, the median follow- up for survival was 22 months, approximately 8 to 10 months shorter than the estimated survival medians. Because less than 5% of the patients were at risk when the estimated medians were reached, the hazard ratio, which analyzes the differences in outcome across the entire follow-up period, is a more accurate characterization of the survival benefit and other late-occurring end points than is the estimate of the median time until the event.

Health-related quality-of-life assessments can reinforce and augment objective measures such as overall survival and radiographic progression. In this population of men with metastatic prostate cancer, deterioration in the quality of life was delayed by enzalutamide, a result suggesting that the treatment effects translated into patient-perceived benefits.

The benefit of enzalutamide was achieved with a favorable safety profile. Grade 3 or higher adverse events were more common in enzalutamide- treated patients than in placebo-treated patients (43% vs. 37%), a finding that was probably influenced by the fact that the safety-reporting period for the enzalutamide group was approximately 1 year longer than that for the placebo group. The safety profile is further illustrated by the 9-month delay in the median time until the first adverse event of grade 3 or higher in the enzalutamide group. A similar proportion of patients in each group (6%) discontinued treatment because of an adverse event.

The safety profile was generally consistent with that previously reported for enzalutamide in patients who had received previous chemotherapy, with a few exceptions.7 Seizure, which was previously observed in the enzalutamide group among patients who had received chemotherapy, occurred in a single patient (0.1%) in each group in our study. Both patients had a history of seizure that was unknown to investigators at the time of enrollment. Hypertension was more commonly observed in the enzalutamide group than in the placebo group (13% vs. 4%) and occurred more often in patients with a medical history of hypertension. These events were not associated with symptoms of mineralo-corticoid excess or an increased risk of cardiovascular or renal sequelae and generally were managed with the use of standard therapies. In contrast to other antiandrogens, enzalutamide was not associated with hepatotoxicity. Other adverse events that were reported more frequently in the enzalutamide group than in the placebo group included fatigue or asthenia, back pain, hot flush, and falls.

Although chemotherapy has been shown to improve overall and progression-free survival in men with metastatic prostate cancer,20,21 many patients do not receive such therapy primarily because of preexisting medical conditions or associated toxic effects.22–24 Thus, there is a need for effective, convenient, and less toxic therapies. Sipuleucel-T showed an overall survival advantage in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic men, most of whom had not received chemotherapy, but did not induce tumor responses or delay disease progression or deterioration in quality of life.19 Radium-223 was recently shown to extend survival in men with symptomatic castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases.25 Abiraterone plus prednisone, which was recently compared with prednisone in patients with metastatic prostate cancer8 who had not received chemotherapy, improved progression- free survival, lengthened the time until a quality-of-life deterioration, delayed chemotherapy use, and was associated with a trend in favor of an overall survival benefit that did not reach statistical significance. Treatment with abiraterone requires concomitant use of prednisone to ameliorate symptoms of mineralocorticoid excess, including fluid overload, hypokalemia, and hypertension.8,9

Multiple agents are now reported to improve survival for patients with metastatic prostate cancer that has progressed after androgen-deprivation therapy. The most effective use of these therapies (order of administration, duration of treatment, and efficacy of combinations) has not yet been defined.

In conclusion, in men with minimally symptomatic or asymptomatic metastatic prostate cancer who had not received chemotherapy, enzalutamide, an oral therapy with an excellent side-effect profile, significantly delayed radiographic disease progression or death, the need for cytotoxic chemotherapy, and the deterioration in quality of life and significantly improved overall survival.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by Medivation and Astellas Pharma, which also funded editorial support.

We thank the patients who volunteered to participate in this study for their dedication and the study-site staff who cared for them.

APPENDIX

The authors are as follows: Tomasz M. Beer, M.D., Andrew J. Armstrong, M.D., Sc.M., Dana E. Rathkopf, M.D., Yohann Loriot, M.D., Cora N. Sternberg, M.D., Celestia S. Higano, M.D., Peter Iversen, M.D., Suman Bhattacharya, Ph.D., Joan Carles, M.D., Ph.D., Simon Chowdhury, M.D., Ph.D., Ian D. Davis, M.B., B.S., Ph.D., Johann S. de Bono, M.B., Ch.B., Ph.D., Christopher P. Evans, M.D., Karim Fizazi, M.D., Ph.D., Anthony M. Joshua, M.B., B.S., Ph.D., Choung-Soo Kim, M.D., Ph.D., Go Kimura, M.D., Ph.D., Paul Mainwaring, M.B., B.S., M.D., Harry Mansbach, M.D., Kurt Miller, M.D., Sarah B. Noonberg, M.D., Ph.D., Frank Perabo, M.D., Ph.D., De Phung, B.S., Fred Saad, M.D., Howard I. Scher, M.D., Mary-Ellen Taplin, M.D., Peter M. Venner, M.D., and Bertrand Tombal, M.D., Ph.D.

The authors’ affiliations are as follows: OHSU Knight Cancer Institute, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland (T.M.B.); Duke Cancer Institute Divisions of Medical Oncology and Urology, Duke University, Durham, NC (A.J.A.); Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and Weill Cornell Medical College, New York (D.E.R., H.I.S.); Institut Gustave Roussy, University of Paris Sud, Villejuif, France (Y.L., K.F.); San Camillo and Forlanini Hospitals, Rome (C.N.S.); Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, University of Washington, Seattle (C.S.H.); Rigshospitalet at the University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen (P.I.); Medivation, San Francisco (S.B., H.M., S.B.N.); Department of Medical Oncology, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, and Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology, Barcelona (J.C.); Guy’s Hospital (S.C.) and Royal Marsden Hospital and Institute of Cancer Research (J.S.B.) — both in London; Monash University and Eastern Health, Clayton, VIC (I.D.D.), and Icon Cancer Care, South Brisbane, QLD (P.M.) — both in Australia; University of California, Davis, Comprehensive Cancer Center, Sacramento (C.P.E.); Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Toronto (A.M.J.), Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal, Montreal (F.S.), and Cross Cancer Institute and University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB (P.M.V.) — all in Canada; Asan Medical Center, Seoul, South Korea (C.-S.K.); Nippon Medical School, Tokyo (G.K.); Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin (K.M.); Astellas Pharma Global Development, Northbrook, IL (F.P., D.P.); Dana–Farber Cancer Institute, Boston (M.-E.T.); and Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc, Brussels (B.T.).

Footnotes

Presented in part at the American Society of Clinical Oncology Genitourinary Cancers Symposium, San Francisco, January 31–February 4, 2014.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [Erratum, CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:134.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huggins C, Hodges CV. Studies on prostatic cancer. I. The effect of castration, of estrogen and of androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate. Cancer Res. 1941;1:293–297. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.22.4.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolla M, Gonzalez D, Warde P, et al. Improved survival in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy and goserelin. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:295–300. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199707313370502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Messing EM, Manola J, Yao J, et al. Immediate versus deferred androgen deprivation treatment in patients with node-positive prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:472–479. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70700-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nair B, Wilt T, MacDonald R, Rutks I. Early versus deferred androgen suppression in the treatment of advanced prostatic cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;1:CD003506. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Studer UE, Whelan P, Wimpissinger F, et al. Differences in time to disease progression do not predict for cancer-specific survival in patients receiving immediate or deferred androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: final results of EORTC randomized trial 30891 with 12 years of follow-up. Eur Urol. 2013 Jul 24; doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.07.024. (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1187–1197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryan CJ, Smith MR, de Bono JS, et al. Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:138–148. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209096. [Erratum, N Engl J Med 2013;368:584.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, et al. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1995–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen CD, Welsbie DS, Tran C, et al. Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat Med. 2004;10:33–39. doi: 10.1038/nm972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knudsen KE, Scher HI. Starving the addiction: new opportunities for durable suppression of AR signaling in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4792–4798. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montgomery RB, Mostaghel EA, Vessella R, et al. Maintenance of intratumoral androgens in metastatic prostate cancer: a mechanism for castration-resistant tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4447–4454. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Attard G, de Bono JS. Translating scientific advancement into clinical benefit for castration-resistant prostate cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:3867–3875. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Massard C, Fizazi K. Targeting continued androgen receptor signaling in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:3876–3883. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tran C, Ouk S, Clegg NJ, et al. Development of a second-generation antiandrogen for treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Science. 2009;324:787–790. doi: 10.1126/science.1168175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scher HI, Beer TM, Higano CS, et al. Antitumour activity of MDV3100 in castration- resistant prostate cancer: a phase 1–2 study. Lancet. 2010;375:1437–1446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60172-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scher HI, Halabi S, Tannock I, et al. Design and end points of clinical trials for patients with progressive prostate cancer and castrate levels of testosterone: recommendations of the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1148–1159. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration- resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:411–422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1502–1512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1147–1154. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61389-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris V, Lloyd K, Forsey S, Rogers P, Roche M, Parker C. A population-based study of prostate cancer chemotherapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2011;23:706–708. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engel-Nitz NM, Alemayehu B, Parry D, Nathan F. Differences in treatment patterns among patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer treated by oncologists versus urologists in a US managed care population. Cancer Manag Res. 2011;3:233–245. doi: 10.2147/CMR.S21033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lissbrant IF, Garmo H, Widmark A, Stattin P. Population-based study on use of chemotherapy in men with castration resistant prostate cancer. Acta Oncol. 2013;52:1593–1601. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.770164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, et al. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:213–223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.