Abstract

Subjects with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have elevated brain levels of the selenium transporter selenoprotein P (Sepp1). We investigated if this elevation results from increased release of Sepp1 from the choroid plexus (CP). Sepp1 is significantly increased in CP from AD brains in comparison to non-AD brains. Sepp1 localizes to the trans-Golgi network within CP epithelia, where it is processed for secretion. The cerebrospinal fluid from AD subjects also contains increased levels Sepp1 in comparison to non-AD subjects. These findings suggest that AD pathology induces increased levels of Sepp1 within CP epithelia for release into the cerebrospinal fluid to ultimately increase brain selenium.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, cerebrospinal fluid, choroid plexus, selenium, selenoprotein P, selenoproteins, Sepp1

INTRODUCTION

The choroid plexus (CP), an essential component of the blood-cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) barrier, remains an enigma despite its physiological importance. The epithelial cells influence the composition of and secrete CSF. They filter factors from the blood within closely apposed capillaries and secrete essential growth factors and nutrients into the CSF. However, the transport of these substances remains poorly understood.

Selenoprotein P (Sepp1) transports selenium to the brain and other organs for selenoprotein synthesis. The selenoprotein family is a unique group of proteins (25 in humans) that contain the 21st amino acid, selenocysteine (Sec). The strong reducing properties of selenium are essential for the activity of antioxidant selenoproteins. These include the glutathione peroxidase (Gpx) and thioredoxin reductase (Trnd) families central to the redox and oxidative stress response pathways. Other selenoproteins facilitate the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response [1–3] and regulate ER calcium release [4–7]. Recent studies suggest a preventative role of selenium and selenoproteins in AD and other neurodegenerative disorders [8, 9].

We previously demonstrated an increase in Sepp1 in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) brains and that Sepp1 is present in human CP [10]. The concentration of selenium in brain is highest in CP [11]. CP contains mRNA for most selenoproteins [12]. Recent evidence suggests that Sepp1 enters the brain via the CP [13]. In this study we investigated if increased Sepp1 in AD brains reflects changes in the CP. We report that Sepp1 has elevated levels in AD CP and also in AD CSF. These findings suggest that synthesis and secretion of CP Sepp1 increases in response to excess oxidative stress/inflammation resulting from AD pathology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

HAAS samples

Brain sections of CP and frozen CSF samples were obtained from the Honolulu Asia Aging Study (HAAS). Kuakini Medical Center’s Institutional Review Board approved all studies involving HAAS subjects. Samples were selected from AD subjects with AD pathology (Braak stage 5 or 6) and cognitive impairment (CASI scores below 70) and control subjects of comparable ages that lacked AD pathology and cognitive impairment.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunolabeling was performed as described previously [14]. Samples were de-paraffinized and antigens unmasked by heating in a pressure cooker to 95°C and 15 psi for 20 min in Trilogy alkaline solution with EDTA (Cell Marque), followed by 3min in 90% formic acid. Samples were then blocked in PBS with 5% serum from species that matched the secondary antibody. Tissue was incubated in mouse monoclonal anti-Sepp1 (1:100, AbFrontier clone 37A1) overnight at 4°C in 3% goat serum. The sections were washed then incubated in biotinylated secondary antibody (mouse, 1:200, Vector Laboratories) followed by ABC™ reagent (Vector Laboratories). We applied HRP to the sections and signals were developed with 3, 3-diaminobenzidine hydrochloride (DAB, Vector Laboratories) as per manufacturer’s instructions. The sections were blindly rated from 0 to 3 based on strength of the stain intensity, with 0 indicating an absence of staining and 3 indicating strong staining within the cells.

For immunofluorescence, tissue was incubated in mouse monoclonal anti-Sepp1 (1:100) and rabbit polyclonal anti-TGN38 (1:100, Sigma) overnight at 4°C in 3% goat serum. After several washes, sections were incubated in Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit Alexa 546 and goat anti-mouse 488,1:250, Life Technologies) and imaged with a fluorescent microscope (Zeiss).

Western blot

CSF samples collected at autopsy from a subset of the same subjects and having no signs of hemolysis were analyzed for protein.10 μl of frozen human CSF samples were thawed, mixed with an equal volume of Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad), denatured at 90°C for 10 min, separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Blots were blocked with Odyssey blocking buffer (LiCor Biosciences) for 1 h and then incubated in monoclonal Sepp1 antibody (AbFrontier mouse monoclonal 37A1, 1:100) or goat polyclonal anti-Gpx3 (1:1000, Sigma). After washing with PBS containing 0.1% tween-20 (PBST), the membranes were treated with secondary antibodies labeled with infrared fluorophores (1:5000, LiCor Biosciences) for 45min. After further washes in PBST, blots were imaged with the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LiCor Biosciences). Membranes were later stained with SimplyBlue (Invitrogen), and signals were normalized to the 67 kDa albumin band.

RESULTS

Selenoprotein expression in choroid plexus

Postmortem CP samples were provided by the HAAS. Subjects had Braak stages of 3 or less for the non-AD group and 5 or greater for the AD group. Pathological data from these subjects are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study subjects

| Control (n =10) | AD (n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at death (mean ± SEM) | 82.9 ± 1.6 | 85.3 ± 1.7 |

| Median (and Range) Braak stage | 2.5 (1–3) | 6(5–6)*** |

| Median (and Range) NIA-Reagan: | 0 (0–1) | 2(2–3)*** |

| Median (and Range) brain atrophy | 1 (0–1) | 2(1–3)** |

| Average NFTs/mm2 (mean ± SEM) | 0.05 ± 0.04 | 12.2 ± 3.7** |

| Average neuritic plaques/mm2 (mean ± SEM) | 0.05 ± 0.05 | 5.5 ± 1.2*** |

indicates p< 0.005

indicates <0.0001 versus controls, two-tailed Student’s T-test. HAAS subject information obtained via autopsy. Methods were published previously [21]. All decedents were American-born males of Japanese ancestry living in Hawaii.

Sepp1 is increased in Alzheimer’s disease choroid plexus

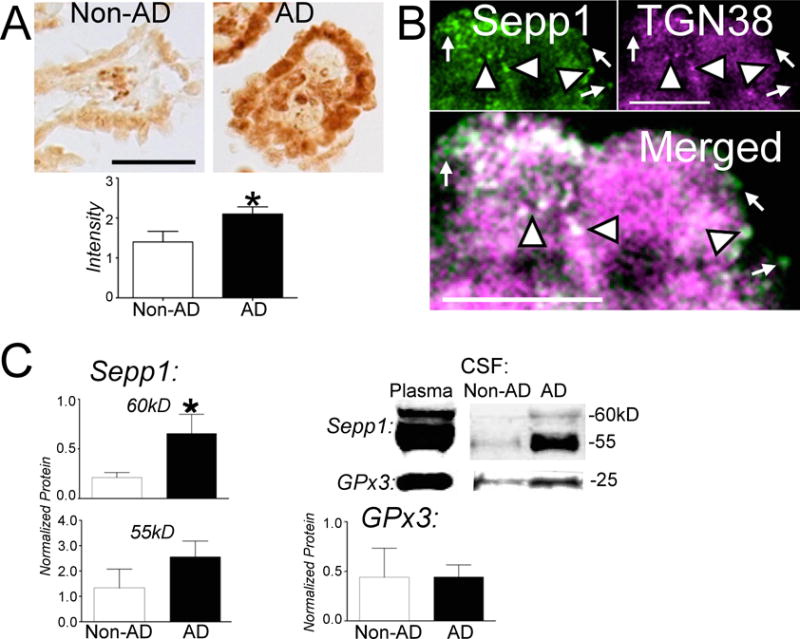

Examination of immunoperoxidase-stained CP sections revealed strong Sepp1 labeling in the epithelial cell layer, with very light staining in connective tissue (Fig. 1A). Sepp1 staining was also present in capillary endothelial cells.

Fig. 1.

A) Immunoperoxidase stain for Sepp1 in non-AD and AD CP. Sections were blindly scored from 0–3 based on stain levels of cells. Graph shows scores for individual subjects with median and interquartile ranges. Sepp1 immunostain had uniform strong staining in AD CP in comparison to non-AD CP (p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test). Scale bar: 50 μM. B) Sepp1 localizes to the trans-Golgi network (TGN). CP was immunolabeled with Sepp1 (green, top left) and TGN38 (magenta, top right). White indicates co-localization. Arrowheads show examples of co-localization of Sepp1 and TGN38, while arrows demonstrate Sepp1 labeling alone. Scale bar: 10 μm. C) Western blot analysis of the two isoforms of Sepp1 and Gpx3 in non-AD and AD CSF normalized to protein concentration. Left: Representative western blots for Sepp1 (above) and Gpx3 (below) in non-AD and AD CSF. Blots of human plasma are shown at left as positive control. Center: Graphs of band densities of Sepp1 60 kDa and 55 kDa isoforms with mean ± SEM. The 60 kDa form represents full-length Sepp1 and is significantly increased in AD CSF in comparison to non-AD CSF (p < 0.05, ANOVA with Bonferonni’s posthoc test). Right: Gpx3 band densities with mean ± SEM.

Sepp1 stained non-AD tissue displayed weak staining of the epithelium with a mean score of 1.9 ± 0.2 (mean ± SEM). In contrast, AD tissue stained for Sepp1 demonstrated uniform strong staining of epithelial cells with a mean score of 2.7 ± 0.2.

Selenoprotein P colocalizes with trans-Golgi network protein TGN38

We sought to determine if Sepp1 in the CP is released into the CSF. We deduced that Sepp1 must traverse the trans-Golgi network before its exocytosis from the CP epithelial cell. Therefore we examined if Sepp1 co-localized to the protein TGN38, a marker for the trans-Golgi network. Fig. 1B shows punctate labeling of Sepp1 throughout CP epithelial cells with absence of labeling only in the nucleus. Although not as abundant as labeled TGN38, Sepp1 largely co-localized with TGN38. Sepp1 was also localized in some vesicular-like structures near cell surfaces that lacked TGN38. This indicates that Sepp1 crosses CP epithelial cells using the trans-Golgi network before it is released into the CSF.

Selenoproteins in Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid

We examined CSF Sepp1 levels for changes between non-AD and AD brain. Western blot confirmed elevated Sepp1 levels in AD CSF compared to non-AD CSF (Fig. 1C). The 60 kDa isoform of Sepp1 was significantly increased approximately 3-fold in AD CSF compared to non-AD CSF. However, the levels of the 55 kDa isoform of Sepp1 and Gpx3 did not differ significantly between non-AD and AD CSF groups.

In summary, these findings suggest increased Sepp1 in AD CP and CSF in response to stress from AD pathology, results in increased brain Sepp1 and selenium levels.

DISCUSSION

These findings demonstrate an increase in Sepp1 in AD CP and CSF. This suggests Sepp1 upregulation in response to stress and/or inflammation within the brain, which occurs as a consequence of AD. CP has an important role in removal of Aβ from the CSF [15].

Sepp1 transports selenium to the brain and other organs [16]. Two possibilities could explain the increased Sepp1 within the CP epithelia. One is that accumulated systemic Sepp1 transported to CP increases Sepp1 within CP epithelia. The second is that Sepp1 is synthesized locally within the CP epithelial cells. The presence of Sepp1 mRNA within CP epithelia supports the second possibility [12]. Sepp1 from CP epithelia can transport selenium throughout the brain via the CSF [13]. Local oxidative stress or increased cytokines in the CSF as a consequence of AD pathology could possibly induce synthesis of Sepp1.

Sepp1 has metal binding and antioxidant properties that may be important in mitigating AD pathology [16]. Sepp1 binds to the ApoER2 (Lrp8) receptor in brain and testes and also binds to the megalin (Lrp2) receptor in kidney. The megalin receptor is implicated in clearing Aβ from CSF [17, 18]. The interaction between Sepp1 and the megalin receptor may influence Aβ clearance.

Sepp1 is a glycosylated protein, and deglycosylation of Sepp1 results in 45 kDa and 35 kDa isoforms [19]. The larger isoform corresponds to the predicted molecular weight of Sepp1 based on the amino acid sequence, while the smaller isoform corresponds to the N-terminal region of Sepp1. Full length Sepp1 has 10 selenocysteins, while the N-terminal region contains one. Studies suggest that the two native (i.e., glycosylated) forms correspond to full-length and N-terminal Sepp1 [20]. Since the amount of glycosylation may vary for both isoforms, this correspondence may not be absolute as the amount of glycosylation may also vary for both isoforms. However, if the larger 60 kDa band in our study primarily corresponds to full-length Sepp1, the increase of this isoform that we observe in AD CSF may indicate that increased selenium transport for synthesis of neuronal and glial selenoproteins. The antigen for making the Sepp1 antibody was Sepp1 purified from human plasma, and the specific epitope of the antibody is unknown. However, our studies of modified Sepp1 suggest the epitopeis likely to be in the N-terminal domain (unpublished), which would enable the antibody to recognize full-length and N-terminal isoforms of Sepp1.

Recent studies suggests that selenium may be effective in the prevention of AD and other neurodegenerative disorders [8, 9]. Selenium supplementation has shown notable potential for reducing AD pathology in animal and cell culture models [8]. Our findings suggest increased synthesis of Sepp1 in CP that results in elevated CSF levels of the protein that could explain the increased Sepp1 in AD brain [10].

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kristen Ewell and Fernando Liquido for assistance, and Elizabeth Nguyen-Wu, Arjun Raman and Marci Reeves for comments and suggestions. This research was supported by Hawaii Community Foundation Ingeborg v.F. McKee Fund 08PR-43031 (FPB), NIH P20RR016467 (FPB), NIH U01AG019349 (LRW), and NIH G12MD007601 (MJB) which supports the JABSOM histology and imaging core facilities.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (http://www.jalz.com/disclosures/view.php?id=2535).

References

- 1.Ye Y, Shibata Y, Yun C, Ron D, Rapoport TA. A membrane protein complex mediates retro-translocation from the ER lumen into the cytosol. Nature. 2004;429:841–847. doi: 10.1038/nature02656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Labunskyy VM, Yoo MH, Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN. Sep15, a thioredoxin-like selenoprotein, is involved in the unfolded protein response and differentially regulated by adaptive and acute ER stresses. Biochemistry. 2009;48:8458–8465. doi: 10.1021/bi900717p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du S, Zhou J, Jia Y, Huang K. SelK is a novel ER stress-regulated protein and protects HepG2 cells from ER stress agent-induced apoptosis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;502:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grumolato L, Ghzili H, Montero-Hadjadje M, Gasman S, Lesage J, Tanguy Y, Galas L, Ait-Ali D, Leprince J, Guerineau NC, Elkahloun AG, Fournier A, Vieau D, Vaudry H, Anouar Y. Selenoprotein T is a PACAP-regulated gene involved in intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and neuroendocrine secretion. FASEB J. 2008;22:1756–1768. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-075820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lescure A, Rederstorff M, Krol A, Guicheney P, Allamand V. Selenoprotein function and muscle disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:1569–1574. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reeves MA, Bellinger FP, Berry MJ. The neuroprotective functions of selenoprotein M and its role in cytosolic calcium regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:809–818. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffmann FW, Hashimoto AC, Shafer LA, Dow S, Berry MJ, Hoffmann PR. Dietary selenium modulates activation and differentiation of CD4+ T cells in mice through a mechanism involving cellular free thiols. J Nutr. 2010;140:1155–1161. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.120725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pillai R, Uyehara-Lock JH, Bellinger FP. Selenium and selenoprotein function in brain disorders. IUBMB Life. 2014;66:229–239. doi: 10.1002/iub.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellinger FP, Weeber EJ. Selenium in Alzheimer’s disease. In: Hatfield DL, Berry MJ, Gladyshev VN, editors. Selenium: Its Molecular Biology and Role in Human Health. 3. Springer Science+Business Media, LLC; New York: 2012. pp. 433–442. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bellinger FP, He QP, Bellinger MT, Lin YL, Raman AV, White LR, Berry MJ. Association of selenoprotein P with Alzheimer’s pathology in human cortex. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;15:465–472. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-15313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuhbacher M, Bartel J, Hoppe B, Alber D, Bukalis G, Brauer AU, Behne D, Kyriakopoulos A. The brain selenoproteome: Priorities in the hierarchy and different levels of selenium homeostasis in the brain of selenium-deficient rats. J Neurochem. 2009;110:133–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, Zhou Y, Schweizer U, Savaskan NE, Hua D, Kipnis J, Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN. Comparative analysis of selenocysteine machinery and selenoproteome gene expression in mouse brain identifies neurons as key functional sites of selenium in mammals. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2427–2438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burk RF, Hill KE, Motley AK, Winfrey VP, Kurokawa S, Mitchell SL, Zhang W. Selenoprotein P and apolipoprotein E receptor-2 interact at the blood-brain barrier and also within the brain to maintain an essential selenium pool that protects against neurodegeneration. FASEB J. 2014;28:3579–3588. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-252874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bellinger FP, He QP, Bellinger MT, Lin Y, Raman AV, White LR, Berry MJ. Association of selenoprotein p with Alzheimer’s pathology in human cortex. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;15:465–472. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-15313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alvira-Botero X, Carro EM. Clearance of amyloid-beta peptide across the choroid plexusinAlzheimer’sdisease. Curr Aging Sci. 2010;3:219–229. doi: 10.2174/1874609811003030219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burk RF, Hill KE. Selenoprotein P-Expression, functions, and roles in mammals. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:1441–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carro E, Spuch C, Trejo JL, Antequera D, Torres-Aleman I. Choroid plexus megalin is involved in neuroprotection by serum insulin-like growth factor I. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10884–10893. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2909-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alvira-Botero X, Perez-Gonzalez R, Spuch C, Vargas T, Antequera D, Garzon M, Bermejo-Pareja F, Carro E. Megalin interacts with APP and the intracellular adapter protein FE65 in neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2010;45:306–315. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steinbrenner H, Alili L, Stuhlmann D, Sies H, Brenneisen P. Post-translational processing of selenoprotein P: Implications of glycosylation for its utilisation by target cells. Biol Chem. 2007;388:1043–1051. doi: 10.1515/BC.2007.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meplan C, Nicol F, Burtle BT, Crosley LK, Arthur JR, Mathers JC, Hesketh JE. Relative abundance of selenoprotein P isoforms in human plasma depends on genotype, se intake, and cancer status. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:2631–2640. doi: 10.1089/ARS.2009.2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White L, Petrovitch H, Ross GW, Masaki KH, Abbott RD, Teng EL, Rodriguez BL, Blanchette PL, Havlik RJ, Wergowske G, Chiu D, Foley DJ, Murdaugh C, Curb JD. Prevalence of dementia in older Japanese-American men in Hawaii: The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. JAMA. 1996;276:955–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]