Abstract

Background

Current data on the pathologic diagnoses of breast biopsy after mammography can inform patients, clinicians, and researchers about important population trends.

Methods

Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium data on 4,020,140 mammograms between 1996 and 2008 were linked to 76,567 pathology specimens. Trends in diagnoses in biopsies by time and risk factors (patient age, breast density, and family history of breast cancer) were examined for screening and diagnostic mammography (performed for a breast symptom or short interval follow-up).

Results

Of the total mammograms, 88.5% were screening and 11.5% diagnostic; 1.2% of screening and 6.8% of diagnostic mammograms were followed by biopsies. The frequency of biopsies over time was stable after screening mammograms, but increased after diagnostic mammograms. For biopsies obtained after screening, frequencies of invasive carcinoma increased over time for women aged 40–49 and 60–69, DCIS increased for 40–69, while benign diagnoses decreased for all ages. No trends in pathology diagnoses were found following diagnostic mammograms. Dense breast tissue was associated with high-risk lesions and DCIS relative to non-dense breast tissue. Family history of breast cancer was associated with DCIS and invasive cancer.

Conclusions

While the frequency of breast biopsy after screening mammography has not changed over time, the percentages of biopsies with DCIS and invasive cancer diagnoses have increased. Among biopsies following mammography, women with dense breasts or family history of breast cancer were more likely to have high-risk lesions or invasive cancer. These findings are relevant to breast cancer screening and diagnostic practices.

Keywords: breast cancer diagnosis, breast biopsy, breast pathology, mammography, false positive, atypia, ductal carcinoma in situ

Introduction

While incidence rates and trends of invasive breast cancer and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) are closely monitored across populations and over time, looking at the frequency of breast biopsy and specific pathology diagnoses rendered (including non-cancer diagnoses) in biopsies following screening can illuminate diagnostic trends and mammography performance in different ways. Many studies have focused on the sensitivity and specificity of mammography in detecting breast cancer, including factors that affect performance,7–11 but very few have characterized the frequency of tissue biopsy following mammography and the respective pathology diagnoses at the population level over time. This information can inform clinicians and researchers about important population trends in the mammographic identification of clinically relevant breast lesions and additional factors associated with specific pathologic diagnoses. It also may provide useful information to patients who have undergone biopsy after mammography about the frequencies of subsequent benign, high risk, in situ and invasive cancer diagnoses.

Previous analysis of data from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC), a large registry of women undergoing mammography in the United States, described the frequencies of breast pathology diagnoses from tissue specimens collected from 1996 to 2001.1 This previous BCSC report revealed that rates of both recommending and performing a tissue sample varied little with patient age, and it detailed the frequencies of the highest order pathology diagnoses found in tissue samples. Unlike other sources, the BCSC data include benign and high-risk lesions, such as atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) and lobular neoplasia (LN), in addition to DCIS and invasive cancer.2,3

The purpose of this analysis is to provide updated population-based estimates from the BCSC of the frequencies of specific benign, high-risk, and malignant pathology diagnoses following screening and diagnostic mammography over a 13-year time period and describe trends over time. This analysis also evaluates differences in diagnoses following screening versus diagnostic mammography and associations between specific pathologic diagnoses and breast density and family history of breast cancer.

Methods

Study Population

The BCSC is a collaborative network of seven mammography registries that link to pathology and/or tumor registries, and is supported by a central Statistical Coordinating Center. Additional details on the BCSC and their data collection methods are available at http://breastscreening.cancer.gov. Data collected include patient demographic and risk factor information, mammographic information (e.g. indication for exam, BI-RADS interpretation,4 breast density), and pathology and tumor characteristics. Five of the seven population-based registries of the BCSC (western Washington, New Hampshire, North Carolina, New Mexico, Vermont) contributed data to the current analyses.2 Each BCSC registry and the SCC, where analyses were performed, received institutional review board approval for either active or passive consenting processes or a waiver of consent to enroll participants, link data, and perform analytic studies. All registries and the SCC follow procedures that are Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliant and have received a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality and other protections for the identities of women, physicians, and facilities.5 Screening and diagnostic mammograms between January 1, 1996 and October 31, 2008 included in this study provided at least fourteen months of pathology follow-up data following the mammogram.

Mammography Data Definitions

Standard BCSC definitions were used to categorize mammograms as screening or diagnostic based on the indication for the exam.2 Screening mammograms obtained on women with a prior diagnosis of breast cancer or breast imaging during the preceding 9 months were excluded, as this sequence suggests the current mammogram is diagnostic in nature.6 Diagnostic mammograms included those obtained for short interval follow-up or evaluation of a breast problem. Diagnostic mammograms obtained for additional evaluation of a recent screening mammogram were not included because a biopsy resulting from this sequence was attributed to the initial screening mammogram and already included in the data set.

Screening and diagnostic mammograms were linked to a tissue sample if the tissue sample was obtained within the 12 months following the index mammogram, and before a second mammogram occurred within the 12 month follow-up period.

Pathology Data

Diagnostic pathology tissue samples included needle core biopsy, excisional biopsy, lumpectomy, partial mastectomy, and total mastectomy. Non-epithelial malignancies (e.g., lymphoma, sarcoma), phyllodes tumors, or diagnoses resulting from nipple or fine needle aspiration, breast reduction, or implant removal were excluded. Diagnoses were classified from most to least severe according to the following hierarchy: invasive carcinoma, ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH: ductal, unspecified, mixed type, or other), lobular in situ neoplasia (LN: lobular carcinoma in situ or atypical lobular hyperplasia), and benign/non-atypical (e.g., fibroadenoma, calcifications, ductal hyperplasia, other benign findings, and normal). The “highest order” pathology diagnosis was defined in the following manner: 1) Individual tissue samples that exhibited more than one pathology diagnosis were classified by the most severe pathology finding; and 2) if multiple tissue samples were found within one year of the index mammogram, the first sample was used unless more severe pathology was found in a specimen within 60 days of the original sample. Because specimen laterality was taken into account, one mammography examination could be linked to as many as three different types of tissue samples (right, left, or bilateral breast samples); the worst diagnosis in each breast was recorded separately. If only one tissue sample was obtained during the 12-month follow-up period and data on breast laterality was missing, the sample was included. Because in 98.3% of tissue samples, the most severe diagnosis was established by the first tissue sample following a mammogram, the term “biopsy” is used throughout the manuscript to refer to the tissue sample on which that diagnosis was established.

Pathology Characteristics of Cancers

Pathologic characteristics of cancer (invasive carcinoma and DCIS), including grade, Estrogen Receptor (ER) status, and HER2 status (invasive carcinoma only) were ascertained from records in the pathology and/or cancer registry files.2

Analysis

Characteristics of patients (age, race/ethnicity, first-degree family history of breast cancer, previous biopsy/aspiration, current use of post-menopausal hormone therapy [HT], and time since last mammogram) and of mammograms (breast density, digital or film) were computed separately for screening and diagnostic mammograms and for mammograms followed by a tissue sample. To determine time trends, mammograms were divided into three similarly sized groups based on the distribution of the total numbers of mammograms over the study period: 1996–1999, 2000–2002, and 2003–2008. The percent of mammograms linked to biopsies within one year was computed for each mammogram-year group and age group. Within each age group, trends between mammogram-year group and presence of a biopsy during follow-up were examined using one-sided p-values from Cochran Armitage tests for trend.7,8

Among biopsies following mammography, overall associations between pathology diagnoses and exam-year group were examined within each age group using general chi-squared tests. If the overall chi-squared test indicated a statistically significant association, further chi-squared tests were used to examine the association between exam year group and each diagnosis separately.

Breast density, defined as dense (heterogeneously dense or extremely dense) and not dense (entirely fatty or scattered densities), was based on the BI-RADS density categories.4 Family history of breast cancer was coded as “yes” if a woman self-reported at least one first-degree relative (mother, daughter, sister) with a history of breast cancer.

Among biopsies following screening mammography, chi-squared tests were used to compare distributions of pathology diagnoses across breast density and family history categories within each age group. If the overall chi-squared test was statistically significant, associations between each diagnosis and breast density/family history of breast cancer status were examined.

All p-values, except those from the trend tests, were two-sided and were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Mammography Examination Data

A total of 4,020,140 mammograms from 1,288,886 women, performed between 1996 and 2008, were included in this analysis. Diagnostic mammography comprised 11.5% of examinations, and 88.5% were screening examinations. The median number of mammograms was two per woman (range 1–16). Diagnostic mammograms were more likely to be performed on women who had one of the following characteristics: younger than 40 years, dense breast tissue (heterogeneously dense or extremely dense), previous breast biopsy or aspiration, or mammogram in the previous 12 months (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics and Breast Biopsy Frequencies for Screening and Diagnostic Mammograms

| Total Mammograms | Screening | Diagnostic | Total followed by a biopsy |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL | N 4020140 |

col % (100.0) |

N 3557318 |

row % (88.5) |

N 462822 |

row % (11.5) |

N 74201 |

row % (1.8) |

| Age at mammogram | ||||||||

| 18–39 | 217007 | (5.4) | 148599 | (68.5) | 68408 | (31.5) | 8178 | (3.8) |

| 40–49 | 1182420 | (29.4) | 1041702 | (88.1) | 140718 | (11.9) | 22451 | (1.9) |

| 50–59 | 1186855 | (29.5) | 1070719 | (90.2) | 116136 | (9.8) | 19440 | (1.6) |

| 60–69 | 767754 | (19.1) | 695256 | (90.6) | 72498 | (9.4) | 12422 | (1.6) |

| 70–79 | 506309 | (12.6) | 458210 | (90.5) | 48099 | (9.5) | 8562 | (1.7) |

| 80+ | 159795 | (4.0) | 142832 | (89.4) | 16963 | (10.6) | 3148 | (2.0) |

| Breast Density | ||||||||

| Dense | 1668256 | (47.6) | 1460225 | (87.5) | 208031 | (12.5) | 33962 | (2.0) |

| Not Dense | 1833505 | (52.4) | 1656969 | (90.4) | 176536 | (9.6) | 25978 | (1.4) |

| Missing | 518379 | . | 440124 | 78255 | 14261 | |||

| Type of mammogram | ||||||||

| Digital | 288967 | (7.9) | 263007 | (91.0) | 25960 | (9.0) | 5946 | (2.1) |

| Film | 3378711 | (92.1) | 2982510 | (88.3) | 396201 | (11.7) | 60731 | (1.8) |

| Missing | 352462 | . | 311801 | 40661 | 7524 | |||

| Race | ||||||||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 3127497 | (83.1) | 2767235 | (88.5) | 360262 | (11.5) | 58575 | (1.9) |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 242555 | (6.4) | 213617 | (88.1) | 28938 | (11.9) | 4541 | (1.9) |

| Hispanic | 256642 | (6.8) | 226359 | (88.2) | 30283 | (11.8) | 4619 | (1.8) |

| Asian, Pacific Islander | 50576 | (1.3) | 43939 | (86.9) | 6637 | (13.1) | 1013 | (2.0) |

| Other | 84818 | (2.3) | 76119 | (89.7) | 8699 | (10.3) | 1523 | (1.8) |

| Missing | 258052 | . | 230049 | 28003 | 3930 | |||

| Family hx of breast cancer | ||||||||

| Yes | 529281 | (15.8) | 463498 | (87.6) | 65783 | (12.4) | 12531 | (2.4) |

| No | 2822978 | (84.2) | 2520308 | (89.3) | 302670 | (10.7) | 51428 | (1.8) |

| Missing | 667881 | . | 573512 | 94369 | 10242 | |||

| Previous biopsy/aspiration | ||||||||

| Yes | 774217 | (26.5) | 604321 | (78.1) | 169896 | (21.9) | 23475 | (3.0) |

| No | 2151523 | (73.5) | 1979712 | (92.0) | 171811 | (8.0) | 31944 | (1.5) |

| Missing | 1094400 | . | 973285 | 121115 | 18782 | |||

| HRT use (current) | ||||||||

| Yes | 799714 | (22.6) | 731267 | (91.4) | 68447 | (8.6) | 12789 | (1.6) |

| No | 2743547 | (77.4) | 2435331 | (88.8) | 308216 | (11.2) | 51258 | (1.9) |

| Missing | 476879 | . | 390720 | 86159 | 10154 | |||

| Time since last mammogram: | ||||||||

| <= 12 months | 300749 | (7.9) | 64147 | (21.3) | 236602 | (78.7) | 14340 | (4.8) |

| 1–2 yrs | 2879975 | (76.0) | 2748187 | (95.4) | 131788 | (4.6) | 36940 | (1.3) |

| 3–4 yrs | 239047 | (6.3) | 222815 | (93.2) | 16232 | (6.8) | 5067 | (2.1) |

| > 5 yrs | 134031 | (3.5) | 121438 | (90.6) | 12593 | (9.4) | 4220 | (3.1) |

| Never | 233794 | (6.2) | 195860 | (83.8) | 37934 | (16.2) | 8630 | (3.7) |

| Missing | 232544 | . | 204871 | 27673 | 5004 | |||

Frequency of Biopsy Following Mammography

Overall, 1.8% of mammograms (N=74,201) were followed by breast biopsy; including 1.2% of screening and 6.8% of diagnostic mammograms (Table 1). A total of 76,567 biopsy or other tissue samples were included: 96.8% of mammograms were linked to one tissue sample, 3.1% to two tissue samples, and 0.04% were linked to three samples. The frequency of tissue biopsy among women undergoing screening mammography was similar across age groups and over time (Figure 1; Supplementary Table A). Biopsy among women with diagnostic mammography (performed for breast symptoms or short interval follow-up of a breast problem) was highest in the 18–39 and 80+ age groups and increased significantly over time for women age 50 years and older (p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Pathology Diagnoses of Breast Biopsies Following Mammography

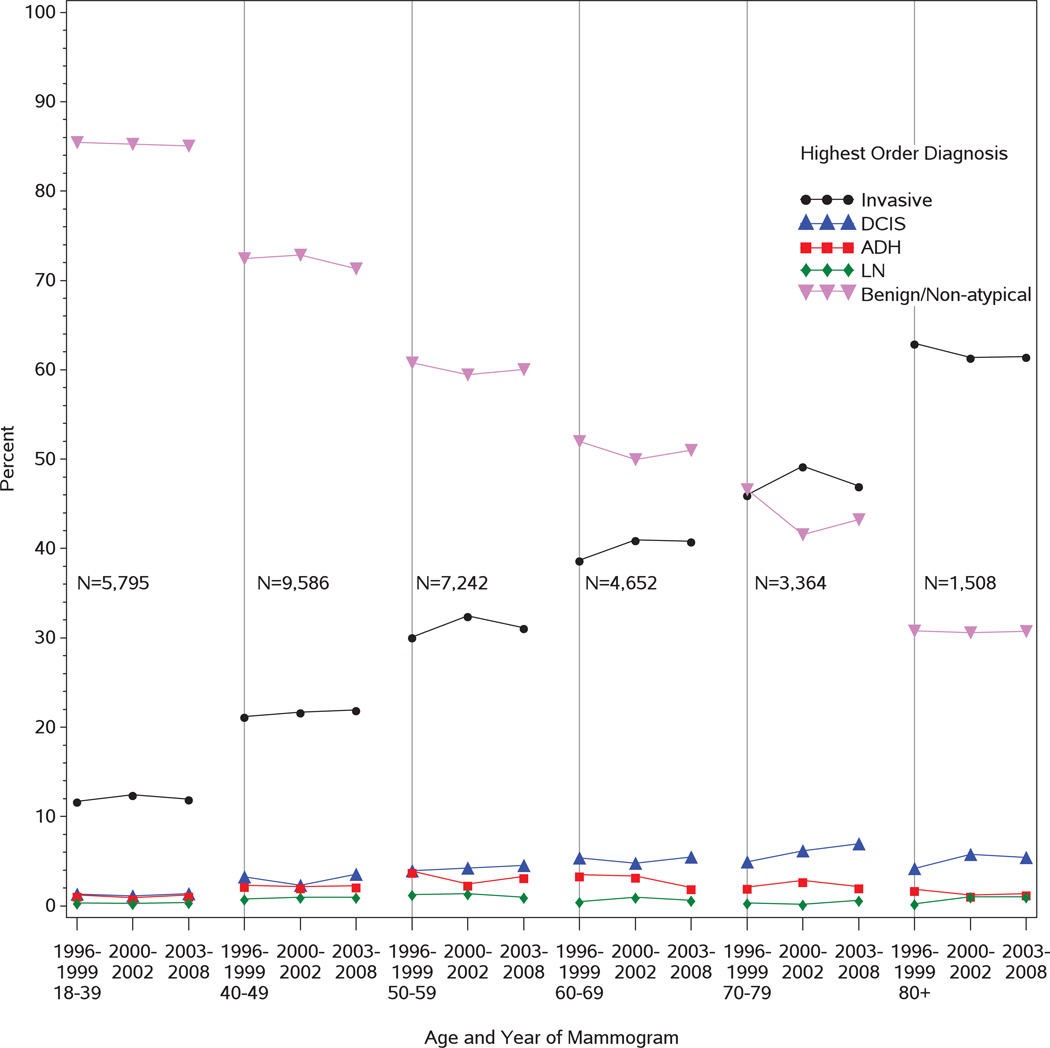

Among biospies after mammography, invasive carcinoma and DCIS frequency increased with age of the patient, while the percentage of samples with benign/non-atypical lesions decreased over time for both screening and diagnostic mammography (Figures 2 and 3; Supplementary Tables B and C). Invasive carcinoma was more frequently diagnosed following diagnostic compared to screening mammography (29.3% vs.19.8%, p< 0.001), while DCIS, high-risk lesions, and benign/non-atypical diagnoses were more frequent following screening mammography.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

For biopsies obtained following screening mammography, time trend analyses indicated significant but mild increases in the frequencies of a highest order diagnosis of invasive carcinoma in the 40–49 and 60–69 age groups (p=0.002 and p=0.006, respectively), and DCIS among women aged 40–69 (p=0.006 for 40–49; p<0.001 for 50–59; p=0.013 for 60–69). High-risk lesions (ADH and LN) had less significant time trends with the exception of a decrease in ADH in the 60–69 age group (p=0.001). However, there were significant decreases in benign diagnoses in all groups over time, including among women aged 40–69 (p<0.001 for 40–49 and 50–59; p=0.009 for 60–69). No significant differences were noted in time trends for pathology diagnoses obtained after diagnostic mammograms.

Risk Factors Associated with Pathology Diagnoses After Screening Mammogram

Screening mammograms from women with dense breasts were more likely to be followed by biopsy than from women without dense breasts (1.3% vs. 1.0%, p<0.001) (Table 1). Biopsies from women aged 40–49 with dense breasts had slightly more invasive cancer than biospies from women without dense breasts (10.1% vs. 8.9%, p=0.033). Biopsies from women under 60 years old (18–59) with dense breasts had significantly more DCIS and high-risk lesions (ADH and LN) and less benign/non-atypical findings than those without dense breasts (Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 1).

Table 2.

Association of Breast Density with Pathology Diagnosis For Breast Biopsies Following Screening Mammogram

| Age at mammogram | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Diagnosis | Breast Density | 18–39 N (%) |

40–49 N (%) |

50–59 N (%) |

60–69 N (%) |

70–79 N (%) |

80+ N (%) |

| Invasive | Dense | 69 (5.2) | 730 (10.1) | 1101 (19.0) | 782 (27.4) | 624 (35.5) | 219 (43.3) |

| Not Dense | 41 (5.1) | 337 (8.9) | 850 (18.9) | 1009 (27.8) | 983 (37.5) | 396 (47.9) | |

| DCIS | Dense | 46 (3.5) | 343 (4.8) | 405 (7.0) | 220 (7.7) | 122 (6.9) | 39 (7.7) |

| Not Dense | 10 (1.2) | 122 (3.2) | 255 (5.7) | 264 (7.3) | 195 (7.4) | 64 (7.7) | |

| ADH | Dense | 27 (2.0) | 247 (3.4) | 257 (4.4) | 113 (4.0) | 62 (3.5) | 15 (3.0) |

| Not Dense | 13 (1.6) | 102 (2.7) | 160 (3.6) | 133 (3.7) | 74 (2.8) | 27 (3.3) | |

| Lobular | Dense | 7 (0.5) | 80 (1.1) | 83 (1.4) | 30 (1.1) | 15 (0.9) | 2 (0.4) |

| Not Dense | 1 (0.1) | 21 (0.6) | 43 (1.0) | 20 (0.6) | 11 (0.4) | 6 (0.7) | |

| Benign/Non-atypical | Dense | 1184 (88.8) | 5793 (80.5) | 3940 (68.1) | 1712 (59.9) | 935 (53.2) | 231 (45.7) |

| Not Dense | 740 (91.9) | 3213 (84.7) | 3181 (70.9) | 2198 (60.7) | 1356 (51.8) | 333 (40.3) | |

”Dense” is defined as heterogeneously dense or extremely dense and “Not Dense” is defined as entirely fatty or scattered densities

Note: Percents are with particular diagnosis within each density and age group.

Just under 16% of screening mammograms were in women with a first-degree family history of breast cancer. Screening mammograms from women with a family history were more likely to be followed by biopsy than those from women without a family history (1.6% vs. 1.2%, p<0.001). Women aged 40–59 with a family history had significantly more invasive cancer and DCIS than women without a family history (Table 3 and Supplementary Figure 2). High-risk lesions (ADH and LN) were not associated with family history, and women with a family history had significantly fewer benign/non-atypical findings.

Table 3.

Association of Family History of Breast Cancer with Pathology Diagnosis for Tissue Samples after Screening Mammogram

| Age at mammogram | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Diagnosis | Family Hx of BC | 18–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80+ |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Invasive | Yes | 27 (5.5) | 226 (11.5) | 443 (20.1) | 404 (29.5) | 399 (39.2) | 179 (50.0) |

| No | 71 (4.4) | 914 (9.4) | 1627 (18.2) | 1461 (26.3) | 1261 (35.5) | 487 (44.5) | |

| DCIS | Yes | 20 (4.1) | 124 (6.3) | 178 (8.1) | 109 (8.0) | 85 (8.3) | 33 (9.2) |

| No | 34 (2.1) | 384 (4.0) | 563 (6.3) | 426 (7.7) | 250 (7.0) | 93 (8.5) | |

| ADH | Yes | 10 (2.1) | 65 (3.3) | 93 (4.2) | 57 (4.2) | 34 (3.3) | 8 (2.2) |

| No | 27 (1.7) | 314 (3.2) | 367 (4.1) | 198 (3.6) | 105 (3.0) | 35 (3.2) | |

| Lobular | Yes | 4 (0.8) | 24 (1.2) | 32 (1.5) | 10 (0.7) | 5 (0.5) | 3 (0.8) |

| No | 6 (0.4) | 92 (1.0) | 112 (1.3) | 54 (1.0) | 24 (0.7) | 6 (0.5) | |

| Benign/Non-atypical | Yes | 426 (87.5) | 1526 (77.7) | 1453 (66.1) | 791 (57.7) | 495 (48.6) | 135 (37.7) |

| No | 1483 (91.5) | 7970 (82.4) | 6262 (70.1) | 3417 (61.5) | 1912 (53.8) | 473 (43.2) | |

Family Hx of BC = Family history of breast cancer (self-report of at least one first-degree relative with a history of breast cancer

Note: Percents are with particular diagnosis within each family history group and age group.

Biologic Characteristics of Invasive Carcinoma and DCIS after Screening vs Diagnostic Mammograms

Cancer grade was available for 6,827of 8,505 (80.3%) invasive carcinomas diagnosed after screening mammograms and 7,007 of 9,425 (74.3%) diagnosed after diagnostic mammograms. 30.4% of invasive carcinomas after screening mammograms were Grade 3 versus 45.8% Grade 3 after diagnostic mammograms (p < 0.001) (Table 4). Estrogen receptor status was available on 78.8% of invasive cancers detected after screening mammograms and 71.3% of cancers detected after diagnostic mammograms. The more aggressive, estrogen-receptor negative, breast cancer phenotype accounted for 15.2% of invasive cancers following a screening and 24.7% following a diagnostic mammogram (p < 0.001). HER2 status, which was not collected consistently in earlier years was available in 21% and 19.4% of invasive cancers following a screening or diagnostic mammogram, respectively. HER2 positivity was noted in 15% and 17.7% of invasive cancers following a screening or diagnostic mammogram, respectively.

Table 4.

Characteristics of invasive cancers and DCIS by preceding mammogram indication

| Invasive Cancers | DCIS | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening | Diagnostic | Screening | Diagnostic | ||||||||

| N | % | N | % | p-value** | N | % | N | % | p-value | ||

| Grade* | 1–2 | 4755 | 69.6 | 3798 | 54.2 | < 0.001 | 891 | 50.5 | 375 | 53.5 | 0.1728 |

| 3 | 2072 | 30.4 | 3209 | 45.8 | 875 | 49.5 | 326 | 46.5 | |||

| ER† | Positive | 5680 | 84.8 | 5063 | 75.3 | < 0.001 | 598 | 82.0 | 195 | 77.7 | 0.1312 |

| Negative | 1019 | 15.2 | 1659 | 24.7 | 131 | 18.0 | 56 | 22.3 | |||

| HER2‡ | Positive | 287 | 15.0 | 324 | 17.7 | 0.0257 | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Negative | 1621 | 85.0 | 1502 | 82.3 | -- | -- | -- | -- | |||

Grade is missing for 1678 out of 8505 (19.7%) and 2418 out of 9425 (25.7%) invasive cancers following screening mammograms and diagnostic mammograms respectively; it is missing for 760 out of 2526 (30.1%) and 494 out of 1195 (41.3%) DCIS cancers following screening mammograms and diagnostic mammograms respectively

ER receptor status is missing for 1806 out of 8505 (21.2%) and 2703 out of 9425 (28.7%) invasive cancers following screening mammograms and diagnostic mammograms respectively; it is missing for 1797 out of 2526 (71.1%) and 944 out of 1195 (79.0%) DCIS cancers following screening mammograms and diagnostic mammograms respectively

HER2 status is missing for 6597 out of 8505 (77.6%) and 7599 out of 9425 (80.6%) invasive cancers following screening mammograms and diagnostic mammograms respectively; It was not computed for DCIS cancers.

HER2 status is missing for 6597 out of 8505 (77.6%) and 7599 out of 9425 (80.6%) invasive cancers following screening mammograms and diagnostic mammograms respectively; It was not computed for DCIS cancers.

The percent of DCIS cases that were nuclear grade 3 was similar between those diagnosed following screening and diagnostic mammograms (49.5% vs 46.5% respectively). 18.0% and 22.3% of DCIS diagnoses following a screening or diagnostic mammogram, respectively, were estrogen receptor negative.

DISCUSSION

Our analysis of pathology data, taken from a large, nationally representative population of women after screening and diagnostic mammograms, provides updated information on the frequency and pathology outcomes of breast biopsy in the U.S.. We note that biopsy for women with risk factors such as increased breast density and/or a family history of breast cancer may be more likely to lead to clinically relevant diagnoses of atypia, DCIS and invasive cancer.

We found no statistically significant increases in biopsy rates over time or across age groups after screening mammography; our rates are similar to earlier published data from the BCSC.1 These findings suggest that recommendation and performance of biopsy following mammography screening have been stable over time. However, the frequency of biopsy after diagnostic mammography has increased over time in women aged 50 years or older.

Among breast biopsies following screening mammography, we found a slight increase in the diagnosis of DCIS and invasive cancer over time in many age groups and a concurrent decrease in benign/non-atypical findings over the study time period. Increasing rates of DCIS have been noted since the advent of screening mammography, although more recent data suggest a decline, possibly related to reduced use of menopausal hormone therapy after the publication of data on breast cancer risk related to its use.9,10–13 While our data reflect frequencies of diagnoses amongst tissue biopsies (not rates per woman or per mammogram), these slight increases in DCIS and invasive cancers with concurrent decreases in benign/non-atypical diagnoses may indicate reduced sampling of non-atypical lesions (e.g., fewer “false positive” imaging findings). This may suggest an important trend in radiologic practice with better recognition of cancer verses benign findings on screening mammography. Alternatively, there may have been pathologist “diagnostic drift,” with a lowering of the threshold used to diagnose DCIS or invasive cancer over time or increased sensitivity of pathologist techniques for detecting smaller cancers in tissue samples (e.g. more frequent use of additional levels or special stains). Given that the same trends were not noted in biopsies following diagnostic mammograms for breast symptoms, these potential influences may be specific to the often more subtle presentation of smaller cancers identified in biospies following screening mammography. These trends, while possibly reducing “false positive” benign biopsies after screening mammography, may also contribute to “over-diagnosis” or increased detection of smaller, less aggressive breast cancers that were unlikely to be life-threatening.

Studies examining atypical hyperplasia (including ADH and LN) in screened populations suggest that the overall rates of high-risk lesions are very low (<1% of screens result in a biopsy with atypia).14 However, frequencies in biopsy samples are higher, ranging from 2–14%.15 Our study indicates that the frequency of atypical hyperplasia varies slightly by age but remained steady over time. These results suggest that the detection and diagnosis of high-risk lesions have not been subjected to either increased detection or diagnostic drift.16

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the frequency and pathology outcomes of biopsy following screening verses diagnostic mammography in a large population sample. The higher frequency of biopsy and of invasive cancer and DCIS diagnoses following diagnostic versus screening mammography is likely due to the higher frequency of clinically evident disease compared to the more subtle findings that tend to occur with screening mammography. However, explaining the time trend increase in the frequency of biopsy following diagnostic mammography is more challenging. Radiologists may be getting better at selecting which patients to send for diagnostic mammograms. Alternatively, there may be an increase in patient-driven requests for biopsy of identified abnormalities or radiologist-driven concerns about potential litigation regarding unsampled abnormalities. In either case, pathologists do not become involved until a biopsy has occurred; thus, the drivers of obtaining biopsy are more likely to be the woman, the radiologists, or perhaps a surgeon or primary care physician.

Dense breast tissue and first-degree family history have both been associated with higher risk of breast cancer.17–19 The presence of either of these factors in our study was significantly associated with increased biopsy rates and clinically significant pathology findings following screening mammography. However, the patterns of diagnoses associated with these two risk factors were slightly different. Biopsies from women with dense breasts had proportionally more high-risk and DCIS lesions, while biopsies from women with a family history had proportionally more DCIS and invasive cancers and proportionally fewer high-risk lesions.

The prior BCSC analysis found that the proportion of lymph node negative invasive breast cancers was lower in a population of patients from SEER (66.1%) compared with the BCSC sample of screened women (78.2%), suggesting that in screened populations, cancers are more frequently diagnosed at an earlier stage.1 Our expanded analyses with additional data indicate that cancers following screening mammography also have more favorable biologic characteristics than those discovered after diagnostic mammography, including lower grade and positive ER status. While our data do not compare screened with unscreened populations directly, others have found that mammographically screened women are more likely to be diagnosed with favorable biology cancers.20,21 While there is concern that some of these screen-detected cancers are “over-diagnosed/over-detected”, in our available BCSC dataset, aggressive phenotypes of breast cancer still account for a significant proportion of cancers following screening examinations, with nearly 30% of invasive cancers classified high grade, 15% ER negative, and almost half of DCIS classified high grade. Given the difficulty in predicting which biologic type of breast cancer may be detected after suspicious findings are identified on screening mammography in a given patient, more significant differences in how we treat and communicate the risks of these different cancer types is another approach to dealing with the issue of “over-diagnosis/over-detection.”

The strengths of our analysis include utilization of a large well-annotated sample that allowed for evaluation of time trends and characteristics associated with outcomes. Limitations included missing data, especially for the biologic characteristics of the cancers.

In conclusion, our analysis of 76,567 breast pathology specimens indicated that the frequency of biopsy after screening mammography did not significantly differ over 13 years or across age groups, but increased over time after diagnostic mammography. The frequency of diagnoses of DCIS and invasive cancer increased over time while benign/non-atypical findings decreased after screening mammography. Women with dense breasts were more likely to have high-risk and DCIS lesions, while those with family histories of breast cancer were more likely to have DCIS and invasive cancer. In addition, cancers following screening mammography were more likely to be lower grade and have positive ER status than those following diagnostic mammography. These findings may help inform breast cancer screening and diagnostic practices and choices for clinicians and patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01 CA140560 and KO5 CA104699 and by the National Cancer Institute-funded Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (HHSN261201100031C). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health. The collection of cancer and vital status data used in this study was supported in part by several state public health departments and cancer registries throughout the U.S. For a full description of these sources, please see: http://www.breastscreening.cancer.gov/work/acknowledgement.html. We thank the BCSC investigators, participating women, mammography facilities, and radiologists for the data they have provided for this study. A list of the BCSC investigators and procedures for requesting BCSC data for research purposes are provided at: http://breastscreening.cancer.gov/.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: All authors have no financial disclosures.

References

- 1.Weaver DL, Rosenberg RD, Barlow WE, et al. Pathologic findings from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium: population-based outcomes in women undergoing biopsy after screening mammography. Cancer. 2006 Feb 15;106(4):732–742. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballard-Barbash R, Taplin SH, Yankaskas BC, et al. Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium: a national mammography screening and outcomes database. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997 Oct;169(4):1001–1008. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.4.9308451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. [Accessed July 24th, 2013];National Cancer Institute, Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) 2013 http://seer.cancer.gov.

- 4.Breast imaging reporting and data system (BI-RADS) Reston, VA: Amercian College of Radiology; 2013. Radiology ACo. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carney PA, Geller BM, Moffett H, et al. Current Medico-legal and Confidentiality Issues in Large Multi-center Research Programs. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2000;152(4):371–378. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hubbard RA, Kerlikowske K, Flowers CI, Yankaskas BC, Zhu W, Miglioretti DL. Cumulative probability of false-positive recall or biopsy recommendation after 10 years of screening mammography: a cohort study. Annals of internal medicine. 2011 Oct 18;155(8):481–492. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cochran WG. Some methods for strengthening the common chi-squared tests. Biometrics. 1954;10(4):417–451. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armitage P. Tests for Linear Trends in Proportions and Frequencies. Biometrics. 1955;11(3):375–386. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Virnig BA, Tuttle TM, Shamliyan T, Kane RL. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a systematic review of incidence, treatment, and outcomes. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2010 Feb 3;102(3):170–178. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bluekens AM, Holland R, Karssemeijer N, Broeders MJ, den Heeten GJ. Comparison of digital screening mammography and screen-film mammography in the early detection of clinically relevant cancers: a multicenter study. Radiology. 2012 Dec;265(3):707–714. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pisano ED, Gatsonis C, Hendrick E, et al. Diagnostic performance of digital versus film mammography for breast-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2005 Oct 27;353(17):1773–1783. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karssemeijer N, Bluekens AM, Beijerinck D, et al. Breast cancer screening results 5 years after introduction of digital mammography in a population-based screening program. Radiology. 2009 Nov;253(2):353–358. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2532090225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerlikowske K, Hubbard RA, Miglioretti DL, et al. Comparative effectiveness of digital vs. film-screen mammography in community practice in the United States: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):493–502. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Picouleau E, Denis M, Lavoue V, et al. Atypical hyperplasia of the breast: the black hole of routine breast cancer screening. Anticancer research. 2012 Dec;32(12):5441–5446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eby PR, Ochsner JE, DeMartini WB, Allison KH, Peacock S, Lehman CD. Frequency and upgrade rates of atypical ductal hyperplasia diagnosed at stereotactic vacuum-assisted breast biopsy: 9-versus 11-gauge. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2009 Jan;192(1):229–234. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bailar JC., 3rd Diagnostic drift in the reporting of cancer incidence. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1998 Jun 3;90(11):863–864. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.11.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerlikowske K, Cook AJ, Buist DS, et al. Breast cancer risk by breast density, menopause, and postmenopausal hormone therapy use. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010 Aug 20;28(24):3830–3837. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.4770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson HD, Zakher B, Cantor A, et al. Risk factors for breast cancer for women aged 40 to 49 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of internal medicine. 2012 May 1;156(9):635–648. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-9-201205010-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yaghjyan L, Colditz GA, Rosner B, Tamimi RM. Mammographic breast density and breast cancer risk by menopausal status, postmenopausal hormone use and a family history of breast cancer. Cancer causes & control : CCC. 2012 May;23(5):785–790. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9936-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu S, Ying Y, Lurdes YT, Munsell MF, Miller AB, Berry DA. Role of detection method in predicting breast cancer survival: Analysis of randomized screening trials. JNCI. 2005 doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehtimaki T, Lundin M, Linder N, et al. Long-term prognosis of breast cancer detected by mammography screening or other methods. Breast cancer research : BCR. 2011;13(6):R134. doi: 10.1186/bcr3080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.