Abstract

Background and Objectives

Clostridium perfringens is more prevalent type of clostridia genus isolated from the intestinal tract of ostrich (Struthio camelus). Necrotic enteritis (NE) is a potentially fatal gastrointestinal (GI) disease of poultry and other avian species, which produces marked destruction of intestinal lining in digestive tract caused by C. perfringens. Pathogenicity and lesions are correlated with the toxins produced, thus toxin typing of the bacterium has diagnostic and epidemiological significance. The aims of the present study were to determine the biotypes of C. perfringens among ostrich’s farms either diseased and healthy ones and to screen the isolates for major toxin genes (cpa, cpb, etx, and iA, cpb2, and cpe).

Materials and Methods

Thirty isolates of C. perfringens were obtained from NE-positive and NE-negative ostrich flocks in Khorasan-e-Razavi porvince and analyzed by multiplex PCR assay.

Results

All isolates were positive for alpha toxin gene (cpa) and five of those were positive for beta toxin gene (cpb). The presence of cpb2 gene was detected in a high percentage of isolates originating from both healthy (93.3%) and diseased flocks (80%). None of the isolate carried enterotoxin gene (cpe).

Conclusion

The results suggest that types A and C of C. perfringens are the most prevalent types in ostrich in Iran. Due to detection of beta2 toxin gene in isolates from both healthy and diseased birds, it appears that the presence of cpb2 is not considered a risk by itself.

Keywords: Necrotic enteritis, ostrich, Struthio camelus, Clostridium perfringens, toxin genes, Iran

INTRODUCTION

In recent decades, ostrich (Struthio camelus) farms are increased in number in Iran. Enteritis can be a major cause of mortality in intensively reared ostrich chicks, practically never occurring in chicks reared on pasture, and it is influenced by a multiple factors. These can be divided into the following categories: intestinal flora, nutrition, environmental factors and pathogens (1). Some viral agents have been isolated from outbreaks of enteritis in ostrich chicks (2). However, in most cases they were not primary pathogens (1, 2). Bacteria play a more important role than viruses, and those involved in ostrich enteritis comprise the Gram-negative bacteria, Campylobacter jejuni, Erysipelothrix rusioopathiae and clostridia (1). Clostridia produce a myriad of potent toxins that are responsible for severe disease in humans and other animals (3). Clostridial enteritis in ostriches is an acute and severe disease able to cause a high mortality among young and adult birds (1). Clostridium perfringens was more prevalent type of clostridia genus that was isolated from the intestinal tract of ostrich (4). Necrotic enteritis (NE) is a potentially fatal gastrointestinal (GI) disease of poultry and other avian species observed with variable frequency, which produces a marked destruction of intestinal lining in the digestive tract caused by C. perfringens (5, 6 ). NE is characterized by reduced growth performance, decreased feed efficiency, and depression in its mild form and by anorexia, severe morbidity, and significant mortality at its worst. C. perfringens is a Gram-positive spore-forming anaerobic bacterium that is widespread in the environment, commonly found in soil and sewage and in the gastro-intestinal tract of animals and humans as a member of the normal gut microbiota (5). C. perfringens causes histotoxic and enteric infections in humans and animals by virtue of production of a large number of toxins (3). There are at least 17 different toxins known, but each individual C. perfringens strain produces a selection of these toxins (5). The differential production of four major toxins, alpha (CPA), beta (CPB), epsilon (ETX), and iota (Iota) toxin, is the basis for classifying C. perfringens isolates into five types, A to E. Alpha toxin is found in all types, whereas the beta toxin can be detected in types B and C only. Moreover, the epsilon toxin can be found in types B and D; and iota toxin in type E only (5). Pathogenicity and lesions are correlated with the major toxins produced, thus typing of the bacterium has diagnostic and epidemiological significance. Toxin typing of C. perfringens is important since particular toxin types are associated with specific enteric diseases in animals. NE is primarily caused by C. perfringens type A and to a lesser extent type C strains (5, 6). Various aspects of NE have been intensively studied for several decades. Despite considerable research efforts, however, the pathogenesis of this condition in poultry and especially in ostriches is still poorly understood. A good deal of research effort has been devoted to characterizing a definitive toxin that is responsible for causing NE in poultry. In addition to the so-called major toxins, there are other minor toxins or enzymes produced by some strains of C. perfringens, which may play a role in pathogenicity (3). These compounds include beta2, NetB, TpeL, delta, theta, kappa, lambda, mu, nu, gamma, eta, neuraminidase, urease and enterotoxin (3, 7). While the roles of beta, iota, and epsilon toxins in enteritis pathogenesis among animals are well documented, the roles of other toxins, such as alpha, NetB, TpeL and beta2 toxin, in NE pathogenesis are still unclear (7- 10). Toxins such as enterotoxin and beta2 toxin have been proposed to be important for the pathogenesis of intestinal disorders (8, 11). The C. perfringens enterotoxin (CPE) mediated food poisoning ranks among the most common foodborne illnesses worldwide (3, 8). Poultry meat is suspected of being the likely vehicle causing food poisoning due to C. perfringens, which is widely distributed in the intestinal contents of healthy and diseased poultry that contaminate carcasses and meat during dressing in abattoirs or poultry processing plants (12). Understanding of the potential reservoirs and routes of transmission of C. perfringens strains causing food poisoning are necessary. Beta2 toxin have been the subject of numerous studies, and the possible association of cpb2-harbouring C. perfringens isolates and the occurrence of enteric disease in humans and domestic and wild animals have been investigated (11).

Various epidemiological and experimental studies of C. perfringens strains from various species of animal and human have been published but very few studies have been published on C. perfringens-induced NE in ostrich and very little knowledge of the C. perfringens genetic profile in ostrich isolate is available. In the present study, for the first time, the collected C. perfringens isolates from healthy and diseased ostrich flocks were analyzed by using a multiplex PCR assay in order to determine the presence of alpha (cpa), beta (cpb), epsilon (etx), iota (iA), beta2 (cpb2), and enterotoxin (cpe) toxin genes.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Bacterial isolation and characterization

The C. perfringens isolates used in this study were isolated from ostriches displaying clinical signs of necrotic enteritis and ostriches dead from other diseases with the exception of enteritis. Samples were obtained from 30 ostrich flocks in Khorasan-e-Rzavi province. Fifteen ostrich flocks were diagnosed as having acute form of NE but fifteen flocks were chosen from apparently healthy flocks. Ostriches from healthy flocks were subjected to the necropsy and isolates of C. perfringens were obtained aseptically with sterile swabs from gut samples of ostriches. In addition, all dead ostriches in diseased flocks were subjected to the necropsy and sampled by scrubbing the intestinal wall of affected birds. Gram stain of tissue specimens from field cases of NE was done, too. Subsequently, 90 intestinal samples were streaked onto blood agar plates containing 7% defibrinated sheep blood and incubated anaerobically at 37°C for 48 hr. Colonies which showed characteristic dual hemolytic zones were picked up and sub-cultured in Tryptose Sulfite Cycloserine agar (TSC) and Tryptose Sulfite Neomycin agar (TSN) for purification. The identity of the isolates was confirmed by their colonial and microscopical morphology, hemolytic pattern and Gram staining. All culture media and additives used in this study were purchased from Merck (Germany). Reference strains of Clostridium perfringens ATCC 13124 (cpa); CIP 106157 (cpa, cpe); CIP 60.61 (cpa, cpb, etx, cpb2) were used as positive controls. All treatments of birds were conducted according to Animal Care Guidelines of the Research Committee, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad.

Multiplex PCR

A single colony of each strain was suspended in 100 μl distilled water, boiled for 10 min and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatants were collected carefully and used as template DNA for PCR (10). Six pairs of primers were used to determine the presence of cpa, cpb, iA, etx, cpe (13), and cpb2 (14) genes using a multiplex PCR technique for all isolates. The primers and other materials used in PCR reaction were provided by Ampliqon (Odense, Denmark). Amplification reactions were carried out in a 50μl reaction volume containing 5 μl 10 x PCR buffer, 5 mM dNTPs, 25 mM MgCl2, 5U of Taq DNA polymerase, 0.5 mM of each cpa oligo, 0.36 mM of each cpb oligo, 0.36 mM of each cpb2 oligo, 0.52 mM of each iA oligo, 0.44 mM of each etx oligo, 0.34 mM of each cpe oligo, and dH2O. Ten μl of template DNA was added to the mixture. Several bacterial strains as positive and negative controls (described above) were included in all PCR reaction sets. Amplification was programmed in a thermocycler (Techne TC-3000, England) as follows: 95°C for 3 min followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min (13). The amplification products were detected by gel electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gel in 1 x TAE buffer, stained with 0.5 μg/ml EtBr. Amplified bands were visualized and photographed under UV transillumination.

Results

Characterization of bacterial isolates

A total of 30 isolates of C. perfringens were obtained from the intestines of ostriches. Fifteen isolates were isolated from NE-positive and the remainders from ostriches without necrotizing enteritis. Only one isolate from each bird was considered. All bacterial isolates exhibited the characteristic features of C. perfringens. The colonial characters on blood agar showed dew drops, smooth, grayish, and convex colonies with a double zone of haemolysis. Clostridium perfringens formed black colonies in TSC and TSN agar. Microscopic characters revealed Gram positive non motile rods with boxcar-shaped square cells. The Gram stain of tissue specimens from field cases of NE demonstrated that rod-shaped bacteria with typical C. perfringens morphology formed large clumps primarily around the necrotic areas, and only seldom, single colonies of C. perfringens were seen in the vicinity of non-necrotic epithelium.

Multiplex PCR

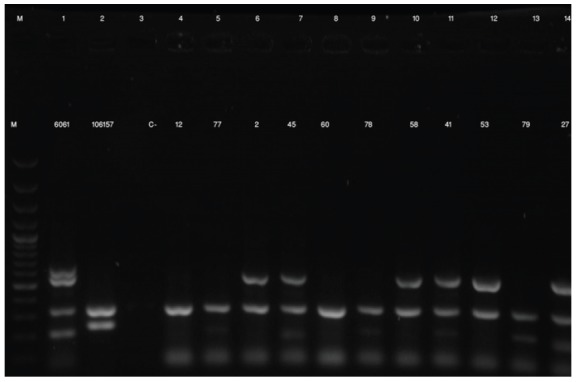

All C. perfringens isolates from NE-positive (No:15) and NE-negative (No:15) ostriches were positive for cpa and negative for etx and iota toxin genes. In addition, 4 isolates (26.6%) from NE-positive and only 1 (6.6%) isolate from NE-negative ostriches were positive for cpb. The results showed that 25 isolates (83.3%) belonged to toxin type A and 5 (16.7%) belonged to toxin type C (Fig. 1). Only one of 5 C types isolates belonged to NE-negative ostriches. All C. perfringens isolates were also negative for cpe gene but 26 out of 30 (86.7%) from diseased and healthy ostrich flocks were positive for cpb2 gene (Fig. 1). Only 1 isolate (3.3%) from NE-negative ostriches was negative for cpb2 gene.

Fig. 1.

Agarose gel (1.5%) electrophoresis of multiplex PCR products of C. perfringens isolates. Lanes M: size marker (GeneRuler 100 bp DNA Ladder, Fermentas); lane 1: Positive control for cpa, cpb, etx and cpb2 (CIP 60.61); lane 2: Positive control for cpa and cpe (CIP 106157); lane 3: Negative control; lanes 5, 9 and 13: field isolates of C. perfringens obtained from healthy and diseased ostriches, that were positive for cpa and cpb (type C); lanes 7, 11 and 14 field isolates of C. perfringens obtained from healthy and diseased ostriches, that were positive for cpa , cpb and cpb2 (type C). lanes 4: field isolates of C. perfringens obtained from healthy ostriches, that were positive for cpa (type A); lanes 6, 10 and 12 field isolates of C. perfringens obtained from healthy and diseased ostriches, that were positive for cpa and cpb2 (type A).

DISCUSSION

Traditionally, typing of C. perfringens strains involved sero-neutralisation of culture filtrates in vivo. Mice or guinea pigs were injected with culture supernatants of C. perfringens, along with antitoxin, and death (mice) or dermonecrosis (guinea pigs) was assessed (15). This assay was extremely time-consuming as growth of the organism was required. It was also expensive as two of the toxins, epsilon and iota, required trypsin for activation, but a third toxin, beta toxin, was inactivated by trypsin. Therefore each culture supernatant was assayed numerous times; with and without trypsin, and with and without the five different preparations of neutralizing antisera (16). Multiplex PCR assay is a useful alternative to traditional assays and as a replacement for standard in vivo typing methods (13). In the present study, a total of 30 isolates of C. perfringens were cultured from the intestines of healthy and diseased ostriches. C. perfringens types A (cpa positive) and C (cpa and cpb positive) were identified in the samples but type A was the dominant type (83.3%). This finding was in agreement with previous studies done on poultry (13, 17, 18). From 5 C. perfringens type C isolates in this study, 4 obtained from NE-positive and only 1 isolate from NE-negative ostriches. Very few studies have been published on genotyping of C. perfringens obtained from ostrich. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the second investigation on genotyping of C. perfringens obtained from ostrich. Songer and Meer (1996) conducted the genotyping of 9 C. perfringens isolates from ostrich by multiplex PCR. All isolates were type A and one isolate was cpe positive (18).

Because C. perfringens type A is highly prevalent in the intestines of healthy animals, controversy exists about its real pathogenic role. The intestinal number of C. perfringens in healthy and in NE-affected birds are different. The C. perfringens population is found to be normally less than l02 to 104 colony-forming units (CFU) per g of the intestinal contents in the small intestine of healthy chickens compared to 107-109 CFU/g in diseased birds (7). The presence of C. perfringens in the intestinal tract or inoculation of the animals with high doses of C. perfringens, however, does generally not lead to the development of necrotic enteritis. One or several predisposing factors may be required to elicit the clinical signs and lesions (5). Additionally, it was shown that strains isolated from necrotic enteritis outbreaks did not produce more alpha toxin compared to isolates from the gut of clinically healthy broilers (19).

Alpha toxin is a phospholipase C sphingomyelinase that hydrolyzes phospholipids and promotes membrane disorganization (3). Until recent years; alpha toxin has been proposed as the main virulence factor for NE in poultry. Recently, the role of C. perfringens alpha toxin in NE is disputed (7, 10, 11, 27). Keyburn et al. described a novel pore-forming toxin, NetB, a virulence factor which is involved in the pathogenesis of NE (10). Subsequent studies showed that netB being the only virulence factor to date shown to be essential in producing disease (7). Severity of disease may vary with the presence of other virulence determinants, of which the best implicated accessory toxin is another novel toxin, TpeL, a member of Large Clostridial Toxins (LCT) family (20), which is present in some type A NE isolates (21). There is evidence that netB-positive strains that are also tpeL-positive cause more severe disease than strains that lack tpeL (22). The presence of netB and tpeL genes among C. perfringens isolated in this study was investigated in separate studies (Unpublished data).

Beta toxin is present in C. perfringens type C found in poultry and we isolated 5 cpb-positive C. perfringens in ostrich isolates in the present study. Beta toxin is thought to be pore-forming in nature, causing increased permeability (3). It is a highly trypsin-sensitive protein (3) which is responsible for mucosal necrosis and possibly for central nervous system signs in C. perfringens-induced disease in domestic animals (6). Although this toxin is cytotoxic, its mode of action has not yet been elucidated in pathogenesis of C. perfringens in avian and typical disease cannot be reproduced by this toxin alone (6).

All isolates tested in this study were cpe-negative. C. perfringens enterotoxin (CPE) is the most important virulence factor when type A isolates cause human GI diseases, although less than 5% of type A isolates produce this toxin (12, 23). In contrast to the well-established role of this toxin in human GI disease, the data implicating CPE in animal disease remains more ambiguous (8). Animals with diarrhea are rarely tested for the presence of CPE in their feces and diagnostic criteria for establishing CPE-mediated animal disease are lacking (8).

Biological activity of beta2 toxin was similar to that of the beta toxin, although it may possess weaker cytotoxic activity. A possible pore formation or other mechanisms leading to cell membrane disruption appear to be its most plausible function (3). CPB2 toxin can be produced by all types of C. perfringens. In this study, we have reported a high percentage of cpb2 gene positive isolates obtained from both healthy (93.3%) and diseased (80%) ostrich flocks. The prevalence of the cpb2 gene in avian isolates is varied among descriptions in the literature (8, 11). The highest (42 out of 43) and lowest (0 out of 41) prevalence of the cpb2 gene among diseased birds were reported in prior studies (17, 24). Several epidemiological studies have shown a wide distribution of β2-toxigenic C. perfringens strains among various healthy and diseased humans, domestic and wildlife animals (11). According to epidemiological data, CPB2- toxin strains are mainly involved in piglet necrotic enteritis and in horse typhlocolitis (3, 8, 11), but previous studies have suggested that the beta2 toxin does not play an important role in necrotic enteritis in birds (3, 11). β2-toxigenic C. perfringens strains were isolated from various species of birds such as chicken, turkey, quail and psittacine (11). To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first investigation on β2-toxigenic C. perfringens isolates from ostrich. In addition, all of the β2-toxigenic C. perfringens isolates obtained from various species of birds were type A and we have reported the first β2-toxigenic C. perfringens type C in birds.

The presence of such genes is, therefore, not considered a risk by itself and there are some predisposing factors that have been associated with the selection of toxigenic C. perfringens and, consequently, the development of disease. However, when interpreting the results it has to be kept in mind that the presence of the gene of a toxin does not necessarily mean, that the toxin is produced, as it was shown for NetB toxin (25) or CPB2 (26).

In conclusion, multiplex PCR provides a simple and rapid assay for genotyping of C. perfringens isolates. This study showed that type A and to a lesser extent type C strains of C. perfringens are the most prevalent types in ostrich in Iran. It also revealed the presence of cpb2 in majority of both healthy and diseased ostriches.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a grant (No. 16142) from the Research Council of the Ferdowsi University of Mashhad. We would like to thank Mr. A. Kargar for his assistance in laboratory works and Dr. Shojadoost from University of Tehran, Iran, for the gift of reference strains.

References

- 1.Huchzermeyer FW. Disease of ostriches and other ratites. Agricultural Research Council, Onderstepoort Veterinary Institute; Pretoria: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Els HJ, Josling D. Viruses and virus-like particles identified in ostrich gut contents. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1998;69:74–80. doi: 10.4102/jsava.v69i3.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Popoff MR, Bouvet P. Clostridial toxins. Future Microbiol. 2009;4:1021–1064. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zandi E, Mohammadabadi MR, Ezatkhah M, Alimolaei M. Identification of Clostridium Isolated from the intestinal tract of ostrich. In: the 13th Iranian and the 2th International Congress of Microbiology. Ardabil University of Medical Sciences. 2012:279. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper KK, Songer JG. Necrotic enteritis in chickens: a paradigm of enteric infection by Clostridium perfringens type A. Anaerobe. 2009;15:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Songer JG. Clostridial enteric diseases of domestic animals. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:216–234. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.2.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shojadoost B, Vince AR, Prescott JF. The successful experimental induction of necrotic enteritis in chickens by Clostridium perfringens: a critical review. Vet Res. 2012;43:74. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-43-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uzal FA, Vidal JE, McClane BA, Gurjar AA. Clostridium perfringens Toxins Involved in Mammalian Veterinary Diseases. The Open Toxinology Journal. 2010;3:24–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Immerseel F, Rood JI, Moore RJ, Titball RW. Rethinking our understanding of the pathogenesis of necrotic enteritis in chickens. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17:32–36. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keyburn AL, Boyce JD, Vaz P, Bannam TL, Bannam TL, Ford ME, Parker D, et al. NetB, a new toxin that is associated with avian necrotic enteritis caused by Clostridium perfringens. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e26. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Asten AJAM, Nikolaou GN, Gröne A. The occurrence of cpb2-toxigenic Clostridium perfringens and the possible role of the β2-toxin in enteric disease of domestic animals, wild animals and humans. Vet J. 2010;183:135. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Songer JG. Clostridia as agents of zoonotic disease. Vet Microbiol. 2010;140:399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meer RR, Songer JG. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction assay for genotyping Clostridium perfringens. Am J Vet Res. 1997;58:702–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bueschel DM, Jost BH, Billington SJ, Trinh HT, Songer JG. Prevalence of cpb2, encoding beta2 toxin, in Clostridium perfringens field isolates: correlation of genotype with phenotype. Vet Microbiol. 2003;94:121–129. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(03)00081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterne M, Batty I. Pathogenic Clostridia. Butterworths; London: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatheway CL. Toxigenic clostridia. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:66–98. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.1.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engström BE, Fermer C, Lindberg A, Saarinen E, Baverud V, Gunnarsson A. Molecular typing of isolates of Clostridium perfringens from healthy and diseased poultry. Vet Microbiol. 2003;94:225–235. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(03)00106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Songer JG, Meer RR. Genotyping of Clostridium perfringens by polymerase chain reaction is a useful adjunct to diagnosis of clostridial enteric disease in animals. Anaerobe. 1996;2:197–203. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gholamiandekhordi AR, Ducatelle R, Heyndrickx M, Haesebrouck F, Van Immerseel F. Molecular and phenotypical characterization of Clostridium perfringens isolates from poultry flocks with different disease status. Vet Microbiol. 2006;113:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amimoto K, Noro T, Oishi E, Shimizu M. A novel toxin homologous to large clostridial cytotoxins found in culture supernatant of Clostridium perfringens type C. Microbiol. 2007;153:1198–1206. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/002287-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chalmers G, Bruce HL, Hunter DB, Parreira VR, Kulkarni RR, Jiang YF, et al. Multilocus sequence typing analysis of Clostridium perfringens isolates from necrotic enteritis outbreaks in broiler chicken populations. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:3957–3964. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01548-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coursodon CF, Glock RD, Moore KL, Cooper KK, Songer JG. TpeL-producing strains of Clostridium perfringens type A are highly virulent for broiler chicks. Anaerobe. 2012;18:117–121. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heikinheimo A, Lindström M, Korkeala H. Enumeration and isolation of cpe-positive Clostridium perfringens spores from feces. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:3992–3997. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.9.3992-3997.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tolooe A, Shojadoost B, Peighambari SM. Molecular detection and characterization of cpb2 gene in Clostridium perfringens isolates from healthy and diseased chickens. J Venom Anim Toxins incl Trop Dis. 2011;17:59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abildgaard, Sondergaard TE, Engberg RM, Schramm A, Højberg O. In vitro production of necrotic enteritis toxin B, NetB, by netB-positive and netB-negative Clostridium perfringens originating from healthy and diseased broiler chickens. Vet Microbiol. 2010;144:231–235. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crespo R, Fisher DJ, Shivaprasad HL, Fernández-Miyakawa ME, Uzal FA. Toxinotypes of Clostridium perfringens isolated from sick and healthy avian species. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2007;19:329–333. doi: 10.1177/104063870701900321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]