Abstract

Liver disease in pregnancy is rare but pregnancy-related liver diseases may cause threat to fetal and maternal survival. It includes pre-eclampsia; eclampsia; haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets syndrome; acute fatty liver of pregnancy; hyperemesis gravidarum; and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Recent basic researches have shown the various etiologies involved in this disease entity. With these advances, rapid diagnosis is essential for severe cases since the decision of immediate delivery is important for maternal and fetal survival. The other therapeutic options have also been shown in recent reports based on the clinical trials and cooperation and information sharing between hepatologist and gynecologist is important for timely therapeutic intervention. Therefore, correct understandings of diseases and differential diagnosis from the pre-existing and co-incidental liver diseases during the pregnancy will help to achieve better prognosis. Therefore, here we review and summarized recent advances in understanding the etiologies, clinical courses and management of liver disease in pregnancy. This information will contribute to physicians for diagnosis of disease and optimum management of patients.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Liver injury, Low platelets, Haemolysis elevated liver enzymes, Acute fatty liver of pregnancy, Hyperemesis gravidarum, Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

Core tip: Liver disease in pregnancy is rare, however, pregnancy-related liver diseases may cause threat to fetal and maternal survival. It includes pre-eclampsia; eclampsia; haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets syndrome; acute fatty liver of pregnancy; hyperemesis gravidarum; and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. To improve the maternal and fetal outcomes, recent basic research and clinical trials have shown the translational results. The present review aimed to summarize these recent information to improve maternal and fetal outcomes. Better knowledge and understandings of etiologies and potential treatment options for these diseases will help physicians to manage the diseases.

INTRODUCTION

Pregnancy causes significant changes in the hormonal state, leading to physiological and biochemical changes in the body. Maternal cardiac output and heart rate increases, however, the hepatic blood flow remains constant. Gall bladder decreases its motility results in the higher risk of developing gallstones. The blood exams during the normal pregnancy show decrease of albumin and uric acid. Alkaline phosphatase increases due to placental secretion. In addition, no changes in the level of aminotransferases and bilirubin are seen[1]. In addition to the exacerbation or recurrence of a pre-existing or co-incident liver disease during pregnancy, a few diseases are directly related to pregnancy. Commonly, they are classified into two major categories depending on their etiological association with or without hypertension. Hypertension-related liver disease during pregnancy includes pre-eclampsia; eclampsia; haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets (HELLP) syndrome; and acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP). The other category includes hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP). Although the severity of diseases are differ, however since the general conditions and hepatic failure can directly lead to maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality, the accurate diagnosis and decision of prompt delivery are essential for managing these diseases. In addition, the possible risks of developing various hepatobiliary diseases in patients’ later life have been recently reported. Therefore, the rapid diagnosis, therapeutic intervention, and close follow-up are necessary for the management of pregnancy-related liver diseases.

To date, the timing of disease occurrence has been considered as a key diagnostic factor. In addition, recent researches have shown the associations of genetic components to disease occurrence and clinical studies have revealed various therapeutic options for these diseases[1-3]. In this review, information currently available for diseases are summarized for accurate diagnosis and treatment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Classification of pregnancy-related liver disease

| HG | ICP |

Hypertension-related liver diseases and pregnancy |

AFLP | ||

| Pre-eclampsia, Eclampsia | HELLP | ||||

| Time (trimester) | 1 | 2 and 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Frequency (%) | 0.3-2.0 | 0.1-1.5 | 5-10 | 0.2-0.6 | 0.01 |

| Clinical features | Nausea | Pruritis | High BP | High BP | Nausea |

| Vomiting | Mild jaundice | Edema | Edema | Vomiting | |

| Dehydration | Mild elevation of transaminase | Proteinuria | Proteinuria | Hypoglycemia | |

| Elevation of bile acids | Seizure | Seizure | Lactic acidosis | ||

| Mild elevation of transaminases | DIC | Severe elevation of transaminases | |||

| Mild to severe elevation of transaminases | |||||

| Pathogenesis -physiologic | starvation, gastric motility, hormonal factors, psychological factors | Hormonal factors | Capillary thrombi, fibrin deposition, endothelial dysfunction, coagulation activation | Microvascular fatty infiltration | |

| Pathogenesis -molecular components | Genetic mutation of LCHAD, Palmitoyltransferase I deficiency | Genetic mutation of MDR3, BSEP | Vascular remodeling, fatty acid oxidation, and immunological factors | Genetic mutation of LCHAD | |

| Managements | Supportive, Hydration | UDCA | BP control | Prompt delivery | Prompt delivery |

| Plasmapheresis | |||||

| Liver transplantation | |||||

| Recurrence | Often | 50%-70% | rare | rare | higher ratio with genetic mutation in LCHAD |

HG: Hyperemesis gravidarum; ICP: Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy; HELLP: Haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets; AFLP: Acute fatty liver of pregnancy; BP: Blood pressure; DIC: Disseminated intravascular coagulation; LCHAD: Long-chain 3-hydroxyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase; MDR3: Multidrug resistance protein; BSEP: Bile salt export protein.

LITERATURE ANALYSIS

A literature search was conducted using PubMed and Ovid, with the term “liver injury”, “pregnancy”, and with each disease classification. The literatures written in English from relevant publications were selected. We summarized the available information on demographics, clinical symptoms, treatment, and the clinical course.

HG

Etiology and clinical features

HG occurs in approximately 0.3%-2.0% of pregnancies during the first trimester[4,5]. It is likely to be multifactorial and starvation, gastric motility, hormonal factors, and psychological factors have been reported to be pathogenesis of HG[5,6]. Relationship of fetal defects of LCHAD[7] and impairment of hepatic carnitine palmitoyltransferase I are involved in genetic pathogenesis of the disease[8]. Risk factors of HG include multiple gestations and fetal anomalies; however, the severity of the symptoms varies in cases and not all women with HG require hospitalization. The clinical symptoms include severe nausea and persistent vomiting during the first trimester of pregnancy. These symptoms lead to dehydration, resulting in weight loss, ketonuria, hypokalemia, hyponatremia, metabolic alkalosis, and erythrocytosis[6]. The liver injury occurs in half of HG patients[2,6] and it has been reported that the severity of clinical symptoms correlate well with the degree of liver enzyme elevation[6,9]. The clinical presentation of HG with liver disease can range from mild aminotransferase elevation to rare severe elevation, with occasional jaundice[6,9]. To date, no specific findings of abdominal ultrasound have been reported with HG.

Management

HG is usually a reversible condition; however, it can recur in subsequent pregnancies with no permanent damage to the liver[9]. The management of HG is supportive that includes bowel rest, intravenous fluid replacement, and possible parenteral nutrition. No therapeutic benefit of corticosteroids has been reported[10].

ICP

Etiology and clinical features

ICP is a reversible cholestatic condition that usually occurs during the third trimester, and although it disappears after delivery, it is well known to recur in subsequent pregnancies. In addition, recent reviews have reported that ICP is related to an increased risk of developing hepatobiliary diseases in later life[11]. Clinical features of ICP include pruritus, jaundice, and increased aminotransferase and bilirubin. In addition, the levels of cytotoxic bile acids such as chenodeoxycholic acid becomes 10-100-times higher than the normal levels. A representative case data is summarized in Table 2. The differential diagnosis from other cholestatic liver diseases such as viral hepatitis and autoimmune liver injuries is essential for the diagnosis. Recently, genetic factors have been reported to be the etiologies of this disease entity. The results of comprehensive analyses of genetic variation in ICP patients have been reported, and common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) around ABCB4 and ABCB11 encoding multidrug resistance protein (MDR3) and bile salt export protein (BSEP), respectively, have been reported as key factors of ICP[2,12-19]. Supporting these studies, combination of these mutations has been reported to be related to severe ICP[20], and a recent report has shown the association of other genetic variations which drive these SNPs[12]. These genetic etiologies result in the significant differences in disease frequency among ethnic groups. For example, we have recently reported the first Japanese case of severe ICP successfully treated with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), preventing fetal death and clinical symptoms. However, much higher rate of 0.1%-1.5% prevalence has been reported in Caucasians[12,13,15,18]. The relation of hormonal factors is another area of interest in ICP research because it occurs during the late phase of pregnancy and resolves after delivery when sex hormone levels return to normal.

Table 2.

Representative laboratory data of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

| Hematology | Biochemistry | ||||

| WBC | 10080/μL | TP | 6.8 g/dL | Bile acid | 89.6 μmol/L |

| RBC | 410 × 104 /μL | Alb | 3.7 g/dL | U acid | 0.9 μmol/L |

| Hb | 13.3 g/dL | BUN | 8 mg/dL | C acid | 21.7 μmol/L |

| Ht | 39.8% | Cre | 0.36 mg/dL | C/BA | 0.24 |

| PLT | 25.5 × 104/μL | T-Bil | 6.3 mg/dL | HbA1c | 4.2% |

| D-Bil | 4.0 mg/dL | Serum marker | |||

| Coagulation | AST | 264 IU/L | HBs Ag | (-) | |

| PT% | 121% | ALT | 545 IU/L | Anti-HBs | (-) |

| ALP | 310 IU/L | Anti-HBc | (-) | ||

| LDH | 241 IU/L | Anti-HCV | (-) | ||

| γ-GTP | 14 IU/L | AFP | 36 ng/mL | ||

| ChE | 137 IU/L | AFP-L3 | 32.8% | ||

| TG | 197 mg/dL | PIVKAII | 44 mAU/mL | ||

| TC | 191 mg/dL | ANA | (-) | ||

| IgG | 908 mg/dL | AMA | (-) | ||

| CRP | 0.05 mg/dL | ||||

TG: Triglyceride; TC: Total cholesterol; IgG: Immunoglobulin G; U acid: Ursodeoxycholic acid; C acid: Chenodeoxycholic acid; AFP: Alpha fetal protein; PIVKA: Protein induced by Vitamin K absence or antagonists-II; ANA: Anti-nuclear antibody; AMA: Anti-mitochondrial antibody. Reconstructed from ref [19] with permission.

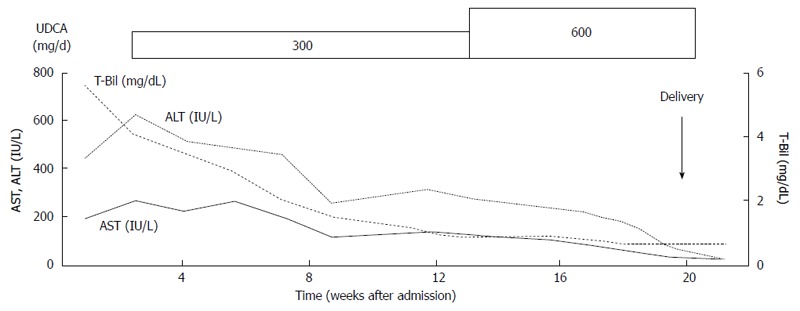

Management

Association of severe ICP with adverse pregnancy outcomes has been reported[21] and recent studies have encouraged the administration of UDCA as a first-line therapy for ICP[22-24]. UDCA is effective by decreasing the levels of serum bile acids, aminotransferase, and bilirubin and for improving pruritus and preventing intrauterine death and meconium passage (Figure 1). ICP usually resolves after delivery and often recurs in subsequent pregnancies (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Clinical course of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. UDCA: Ursodeoxycholic acid; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; T-Bil: Total bilirubin. Reconstructed from ref [19] with permission.

HYPERTENSION-RELATED Liver DISEASES DURING PREGNANCY

Etiology and clinical features

Pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, and HELLP syndrome are related to hypertension during pregnancy. Clinical features of pre-eclampsia include hypertension, proteinuria, and edema and can result in fetal growth retardation. It occurs in 5%-10% of pregnancies during the third trimester[25,26]. Severe pre-eclampsia can be life threatening to the mother and can result in fetal morbidity and mortality. The presence of seizures differentiates eclampsia from pre-eclampsia, and HELLP syndrome is a variant of severe pre-eclampsia characterized by hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet counts, with a frequency of 0.2%-0.6% during pregnancy[27,28]. These three hypertension-related liver diseases share similar clinical presentations, and differentiation is difficult. Serum biochemical analysis shows mild to significant elevations of serum aminotransferases, and no significant increase can be observed in the serum bilirubin concentration. A representative case data is summarized in Table 3. A high level of proteinuria (> 300 mg/d) can also be observed[3]. Capillary thrombi, infarction, fibrin deposition, and red blood cell extravasation, leading to endothelial and hepatic dysfunction, are thought to be pathogenically important[4]. Genetic factors related to vascular remodeling, fatty acid oxidation, and immunological factors have also been implicated as risk factors for these diseases[29-32].

Table 3.

Representative laboratory data of haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets syndrome

| Hematology | Biochemistry | Serum marker | |||

| WBC | 7100 μL | TP | 6.1 g/dL | HBs Ag | (-) |

| RBC | 452 × 104/μL | Alb | 2.4 g/dL | Anti-HBs | (-) |

| Hb | 14.3 g/dL | BUN | 21 mg/dL | Anti-HBc | (-) |

| Ht | 41.2% | Cre | 1.55 mg/dL | Anti-HCV | (-) |

| PLT | 9.7 × 104/μL | T-Bil | 1.7 mg/dL | ANA | (-) |

| D-Bil | 0.9 mg/dL | AMA | (-) | ||

| Coagulation | AST | 137 IU/L | |||

| PT% | 72% | ALT | 106 IU/L | ||

| ATIII | 15% | ALP | 315 IU/L | ||

| FDP | 23.3 μg/mL | LDH | 639 IU/L | ||

| γ-GTP | 151 IU/L | ||||

| ChE | 143 IU/L | ||||

| CRP | 0.62 mg/dL | ||||

WBC: White blood cells; RBC: Red blood cells; Hb: Hemoglobin; Ht: Hematocrit; PLT: Platelet; PT: Prothrombin time; ATIII: Antithrombin III; FDP: Fibrin degradation product; TP: Total protein; Alb: Albumin; BUN: Blood urea nitrogen; Cre: Creatinine; T-Bil: Total bilirubin; D-Bil: Direct bilirubin; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase; γ-GTP: γ-glutamyltransferase; ChE: Choline esterase; CRP: C-reactive protein; ANA: Anti-nuclear antibody; AMA: Anti-mitochondrial antibody.

Management

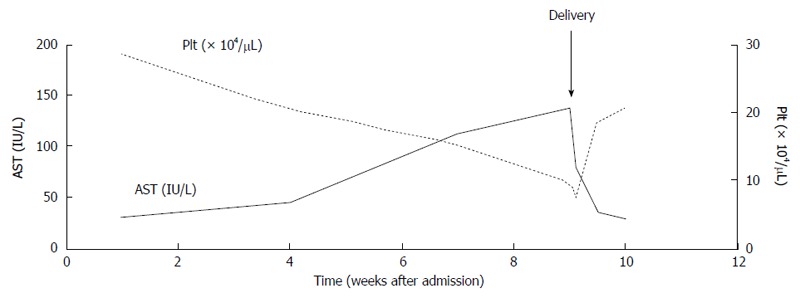

No specific therapy is required for the hepatic involvement of pre-eclampsia, and its only significance is as an indicator of severe disease with a need for immediate delivery to avoid eclampsia, hepatic rupture, or necrosis. The tight control of blood pressure is essential for eclampsia and HELLP syndrome[33], and immediate delivery is necessary in some cases with multi-organ dysfunction, liver infarction or hemorrhage, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), fetal compromise, and others[34-36]. Intravenous administration of magnesium sulfate, and fetal monitoring should be performed to prevent or predict seizures[28]. Effect of corticosteroids is unclear and remains controversial for the patients[37]. The number of platelet and biochemical abnormalities return to normal levels within 2 wk of delivery (Figure 2), however subsequent pregnancies in patients with HELLP syndrome carry a high risk of complications[38].

Figure 2.

Clinical course of haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets syndrome syndrome. AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; PLT: Platelet.

AFLP

Etiology and clinical features

AFLP is a rare but serious condition with an incidence of approximately 1 per 10000 deliveries, and it usually occurs during the third trimester[39-42]. The etiology of this condition has not been fully elucidated; however, abnormal fetal mitochondrial beta oxidation of fatty acids has been reported to be involved as a cause of this condition in the mother[43]. In particular, a fetal defect of long-chain 3-hydroxyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase (LCHAD) due to genetic mutation has been reported to contribute the disease[44]. There are no specific symptoms for the disease, and general fatigue, vomiting, headache, hypoglycemia, and lactic acidosis can be observed. Severe elevation in transaminases, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia, and DIC as well as the signs of renal dysfunction, including elevated blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and proteinuria, can be observed[42,43]. These symptoms are based on the occurrence of microvesicular fat deposition in organs. Liver biopsy is unnecessary for the diagnosis and should be avoided in cases with bleeding tendencies; however, in some cases, it is helpful if it is the early phase of the disease or the symptoms and laboratory data show mild abnormalities. The pathogenesis of the disease includes impaired beta oxidation of fatty acids in hepatic mitochondria, and its fetal defect due to a genetic mutation of LCHAD has been reported to cause either AFLP or HELLP in mothers, with a high frequency of 62%[3,30,31,42]. The histology includes microvesicular steatosis, predominantly in the third zone of the liver, and cytoplasmic ballooning[45].

Management

Early diagnosis and prompt delivery are essential in AFLP. Intensive therapeutic support is necessary for both maternal and fetal survival and plasmapheresis and liver transplantation should be considered in some severe cases[46]. Although AFLP does not have a tendency to recur in subsequent pregnancies in most cases[42], since the recurrence rate is higher in cases with genetic mutation in LCHAD, close follow up is necessary for the groups.

PRE-EXISTING OR CO-INCIDENT LIVER DISEASE DURING PREGNANCY

While pregnancy itself causes significant changes in physiological conditions, effects on pre-existing liver disease and co-incident common liver disease can also be observed in the period[1-3]. The diseases include viral hepatitis[47-52], gallstones[53-55], Budd-Chiari syndrome[56-58], Wilson’s disease[59,60], autoimmune liver diseases[61,62], primary sclerosing cholangitis, primary biliary cirrhosis[63], metabolic disorders, liver tumors[64], and post liver transplantation state[65-67]. For these conditions, there are concerns regarding not only the disease itself but also the toxicity of abovementioned medicines on both mother and fetus. Because of these concerns, the United States Food and Drug Administration classified those medicines into categories A to D for the benefits of usage and the risks of side effects[68,69]. Appropriate therapeutic interventions must be performed on the basis of these datasets. Even with these information however, management of pregnancy with liver cirrhosis is difficult at present.

Viral hepatitis

Hepatitis caused by hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E viruses, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, and Epstein-Barr virus can be observed as exacerbations of chronic hepatitis or acute infection[47-52]. Antiviral treatments can be considered, however, entecavir, lamivudine, adefovir, and interferon are drugs of category C and ribavirin is contraindicated for the pregnancy due to its teratogenicity. If anti-hepatitis B virus treatment is necessary before the delivery, telbivudine and tenofovir should be considered since they are classified into category B.

Gallstones

Increase of cholesterol secretion and decrease of gall bladder motility contribute for the incidence of gallstones. Approximately 10% of patients develop stones or sludge[53-55]. Symptomatic patients should undergo open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy during the second trimester since the outcome is better than medication[55].

Budd-chiari syndrome

Patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome are at high risk of progression of disease during pregnancy because of prothrombotic state[58]. The treatment of anticoagulation is essential at the onset and liver transplantation is necessary in some extreme cases.

Others

Autoimmune liver diseases require continuous management with steroids and immunosuppressive agents. Patients with Wilson’s disease must be treated with penicillamine and require continuous treatment throughout pregnancy to prevent the flare of liver injury[59], however as it is classified into category D and several abnormalities have been reported in children, whose mothers were taking this drug during pregnancy[70,71].

CONCLUSION

Pregnancy-related liver disease is rarer than other liver diseases. However, the clinical importance remains high because it will affect both maternal and fetal clinical courses. Therefore, understanding and knowledge of these disorders are important for physicians to manage patients leading to their benefits.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest: The authors declare that they have no current financial arrangement or affiliation with any organization that may have a direct influence on their work.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: January 22, 2015

First decision: February 10, 2015

Article in press: March 27, 2015

P- Reviewer: Grattagliano I, Kakizaki S, Vezali E S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Joshi D, James A, Quaglia A, Westbrook RH, Heneghan MA. Liver disease in pregnancy. Lancet. 2010;375:594–605. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61495-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed KT, Almashhrawi AA, Rahman RN, Hammoud GM, Ibdah JA. Liver diseases in pregnancy: diseases unique to pregnancy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:7639–7646. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i43.7639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hay JE. Liver disease in pregnancy. Hepatology. 2008;47:1067–1076. doi: 10.1002/hep.22130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weigel MM, Weigel RM. Nausea and vomiting of early pregnancy and pregnancy outcome. An epidemiological study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;96:1304–1311. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1989.tb03228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fell DB, Dodds L, Joseph KS, Allen VM, Butler B. Risk factors for hyperemesis gravidarum requiring hospital admission during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:277–284. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000195059.82029.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abell TL, Riely CA. Hyperemesis gravidarum. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1992;21:835–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Outlaw WM, Ibdah JA. Impaired fatty acid oxidation as a cause of liver disease associated with hyperemesis gravidarum. Med Hypotheses. 2005;65:1150–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Innes AM, Seargeant LE, Balachandra K, Roe CR, Wanders RJ, Ruiter JP, Casiro O, Grewar DA, Greenberg CR. Hepatic carnitine palmitoyltransferase I deficiency presenting as maternal illness in pregnancy. Pediatr Res. 2000;47:43–45. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200001000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conchillo JM, Pijnenborg JM, Peeters P, Stockbrügger RW, Fevery J, Koek GH. Liver enzyme elevation induced by hyperemesis gravidarum: aetiology, diagnosis and treatment. Neth J Med. 2002;60:374–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yost NP, McIntire DD, Wians FH, Ramin SM, Balko JA, Leveno KJ. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of corticosteroids for hyperemesis due to pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:1250–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.obstetgynecol.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marschall HU, Wikström Shemer E, Ludvigsson JF, Stephansson O. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and associated hepatobiliary disease: a population-based cohort study. Hepatology. 2013;58:1385–1391. doi: 10.1002/hep.26444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon PH, Wadsworth CA, Chambers J, Donnelly J, Cooley S, Buckley R, Mannino R, Jarvis S, Syngelaki A, Geenes V, et al. A comprehensive analysis of common genetic variation around six candidate loci for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:76–84. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider G, Paus TC, Kullak-Ublick GA, Meier PJ, Wienker TF, Lang T, van de Vondel P, Sauerbruch T, Reichel C. Linkage between a new splicing site mutation in the MDR3 alias ABCB4 gene and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Hepatology. 2007;45:150–158. doi: 10.1002/hep.21500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Floreani A, Carderi I, Paternoster D, Soardo G, Azzaroli F, Esposito W, Montagnani M, Marchesoni D, Variola A, Rosa Rizzotto E, et al. Hepatobiliary phospholipid transporter ABCB4, MDR3 gene variants in a large cohort of Italian women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:366–370. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trauner M, Fickert P, Wagner M. MDR3 (ABCB4) defects: a paradigm for the genetics of adult cholestatic syndromes. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:77–98. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Floreani A, Carderi I, Paternoster D, Soardo G, Azzaroli F, Esposito W, Variola A, Tommasi AM, Marchesoni D, Braghin C, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: three novel MDR3 gene mutations. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1649–1653. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pauli-Magnus C, Lang T, Meier Y, Zodan-Marin T, Jung D, Breymann C, Zimmermann R, Kenngott S, Beuers U, Reichel C, et al. Sequence analysis of bile salt export pump (ABCB11) and multidrug resistance p-glycoprotein 3 (ABCB4, MDR3) in patients with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Pharmacogenetics. 2004;14:91–102. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200402000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dixon PH, van Mil SW, Chambers J, Strautnieks S, Thompson RJ, Lammert F, Kubitz R, Keitel V, Glantz A, Mattsson LA, et al. Contribution of variant alleles of ABCB11 to susceptibility to intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Gut. 2009;58:537–544. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.159541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamimura K, Abe H, Kamimura N, Yamaguchi M, Mamizu M, Ogi K, Takahashi Y, Mizuno K, Kamimura H, Kobayashi Y, et al. Successful management of severe intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: report of a first Japanese case. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:160. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-14-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keitel V, Vogt C, Häussinger D, Kubitz R. Combined mutations of canalicular transporter proteins cause severe intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:624–629. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geenes V, Chappell LC, Seed PT, Steer PJ, Knight M, Williamson C. Association of severe intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with adverse pregnancy outcomes: a prospective population-based case-control study. Hepatology. 2014;59:1482–1491. doi: 10.1002/hep.26617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chappell LC, Gurung V, Seed PT, Chambers J, Williamson C, Thornton JG. Ursodeoxycholic acid versus placebo, and early term delivery versus expectant management, in women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: semifactorial randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2012;344:e3799. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bacq Y, Sentilhes L, Reyes HB, Glantz A, Kondrackiene J, Binder T, Nicastri PL, Locatelli A, Floreani A, Hernandez I, et al. Efficacy of ursodeoxycholic acid in treating intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1492–1501. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glantz A, Reilly SJ, Benthin L, Lammert F, Mattsson LA, Marschall HU. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: Amelioration of pruritus by UDCA is associated with decreased progesterone disulphates in urine. Hepatology. 2008;47:544–551. doi: 10.1002/hep.21987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sibai BM. Diagnosis and management of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:181–192. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00475-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:S1–S22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baxter JK, Weinstein L. HELLP syndrome: the state of the art. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2004;59:838–845. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000146948.19308.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barton JR, Sibai BM. Diagnosis and management of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets syndrome. Clin Perinatol. 2004;31:807–833, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arias F, Mancilla-Jimenez R. Hepatic fibrinogen deposits in pre-eclampsia. Immunofluorescent evidence. N Engl J Med. 1976;295:578–582. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197609092951102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pollitt RJ. Disorders of mitochondrial long-chain fatty acid oxidation. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1995;18:473–490. doi: 10.1007/BF00710058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilcken B, Leung KC, Hammond J, Kamath R, Leonard JV. Pregnancy and fetal long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency. Lancet. 1993;341:407–408. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92993-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou Y, McMaster M, Woo K, Janatpour M, Perry J, Karpanen T, Alitalo K, Damsky C, Fisher SJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor ligands and receptors that regulate human cytotrophoblast survival are dysregulated in severe preeclampsia and hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets syndrome. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1405–1423. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62567-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barton JR, Sibai BM. Gastrointestinal complications of pre-eclampsia. Semin Perinatol. 2009;33:179–188. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sibai BM, Ramadan MK, Usta I, Salama M, Mercer BM, Friedman SA. Maternal morbidity and mortality in 442 pregnancies with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets (HELLP syndrome) Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:1000–1006. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90043-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sibai BM. Diagnosis, controversies, and management of the syndrome of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:981–991. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000126245.35811.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haddad B, Barton JR, Livingston JC, Chahine R, Sibai BM. Risk factors for adverse maternal outcomes among women with HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count) syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:444–448. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.105915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Varol F, Aydin T, Gücer F. HELLP syndrome and postpartum corticosteroids. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;73:157–159. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(00)00371-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sibai BM, Ramadan MK, Chari RS, Friedman SA. Pregnancies complicated by HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets): subsequent pregnancy outcome and long-term prognosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:125–129. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reyes H, Sandoval L, Wainstein A, Ribalta J, Donoso S, Smok G, Rosenberg H, Meneses M. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy: a clinical study of 12 episodes in 11 patients. Gut. 1994;35:101–106. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Browning MF, Levy HL, Wilkins-Haug LE, Larson C, Shih VE. Fetal fatty acid oxidation defects and maternal liver disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:115–120. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000191297.47183.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knox TA, Olans LB. Liver disease in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:569–576. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608223350807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ibdah JA. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy: an update on pathogenesis and clinical implications. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7397–7404. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i46.7397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ibdah JA, Bennett MJ, Rinaldo P, Zhao Y, Gibson B, Sims HF, Strauss AW. A fetal fatty-acid oxidation disorder as a cause of liver disease in pregnant women. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1723–1731. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906033402204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ong SS, Baker PN, Mayhew TM, Dunn WR. No difference in structure between omental small arteries isolated from women with preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, and normal pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:606–610. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.124287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Minakami H, Takahashi T, Tamada T. Should routine liver biopsy be done for the definite diagnosis of acute fatty liver of pregnancy? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:1690–1691. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)91465-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seyyed Majidi MR, Vafaeimanesh J. Plasmapheresis in acute Fatty liver of pregnancy: an effective treatment. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:615975. doi: 10.1155/2013/615975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee C, Gong Y, Brok J, Boxall EH, Gluud C. Hepatitis B immunisation for newborn infants of hepatitis B surface antigen-positive mothers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD004790. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004790.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schaefer E, Koeppen H, Wirth S. Low level virus replication in infants with vertically transmitted fulminant hepatitis and their anti-HBe positive mothers. Eur J Pediatr. 1993;152:581–584. doi: 10.1007/BF01954085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang J, Zhu Q, Zhang X. Effect of delivery mode on maternal-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus by immunoprophylaxis. Chin Med J (Engl) 2002;115:1510–1512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhattacharya S, O’Donnell K, Dudley T, Kennefick A, Osman H, Boxall E, Mutimer D. Ante-natal screening and post-natal follow-up of hepatitis B in the West Midlands of England. QJM. 2008;101:307–312. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcn007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sookoian S. Effect of pregnancy on pre-existing liver disease: chronic viral hepatitis. Ann Hepatol. 2006;5:190–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khuroo MS, Kamili S. Aetiology, clinical course and outcome of sporadic acute viral hepatitis in pregnancy. J Viral Hepat. 2003;10:61–69. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ko CW, Beresford SA, Schulte SJ, Matsumoto AM, Lee SP. Incidence, natural history, and risk factors for biliary sludge and stones during pregnancy. Hepatology. 2005;41:359–365. doi: 10.1002/hep.20534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu EJ, Curet MJ, El-Sayed YY, Kirkwood KS. Medical versus surgical management of biliary tract disease in pregnancy. Am J Surg. 2004;188:755–759. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rollins MD, Chan KJ, Price RR. Laparoscopy for appendicitis and cholelithiasis during pregnancy: a new standard of care. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:237–241. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8811-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Khuroo MS, Datta DV. Budd-Chiari syndrome following pregnancy. Report of 16 cases, with roentgenologic, hemodynamic and histologic studies of the hepatic outflow tract. Am J Med. 1980;68:113–121. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lim W, Eikelboom JW, Ginsberg JS. Inherited thrombophilia and pregnancy associated venous thromboembolism. BMJ. 2007;334:1318–1321. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39205.484572.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rautou PE, Plessier A, Bernuau J, Denninger MH, Moucari R, Valla D. Pregnancy: a risk factor for Budd-Chiari syndrome? Gut. 2009;58:606–608. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.167577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scheinberg IH, Jaffe ME, Sternlieb I. The use of trientine in preventing the effects of interrupting penicillamine therapy in Wilson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:209–213. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198707233170405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brewer GJ, Johnson VD, Dick RD, Hedera P, Fink JK, Kluin KJ. Treatment of Wilson’s disease with zinc. XVII: treatment during pregnancy. Hepatology. 2000;31:364–370. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schramm C, Herkel J, Beuers U, Kanzler S, Galle PR, Lohse AW. Pregnancy in autoimmune hepatitis: outcome and risk factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:556–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Heneghan MA, Norris SM, O’Grady JG, Harrison PM, McFarlane IG. Management and outcome of pregnancy in autoimmune hepatitis. Gut. 2001;48:97–102. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Poupon R, Chrétien Y, Chazouillères O, Poupon RE. Pregnancy in women with ursodeoxycholic acid-treated primary biliary cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2005;42:418–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Russell P, Sanjay P, Dirkzwager I, Chau K, Johnston P. Hepatocellular carcinoma during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. N Z Med J. 2012;125:141–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Christopher V, Al-Chalabi T, Richardson PD, Muiesan P, Rela M, Heaton ND, O’Grady JG, Heneghan MA. Pregnancy outcome after liver transplantation: a single-center experience of 71 pregnancies in 45 recipients. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:1138–1143. doi: 10.1002/lt.20810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Armenti VT, Radomski JS, Moritz MJ, Gaughan WJ, Gulati R, McGrory CH, Coscia LA. Report from the National Transplantation Pregnancy Registry (NTPR): outcomes of pregnancy after transplantation. Clin Transpl. 2005:69–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nagy S, Bush MC, Berkowitz R, Fishbein TM, Gomez-Lobo V. Pregnancy outcome in liver transplant recipients. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:121–128. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00369-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mahadevan U, Kane S. American gastroenterological association institute technical review on the use of gastrointestinal medications in pregnancy. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:283–311. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mahadevan U, Kane S. American gastroenterological association institute medical position statement on the use of gastrointestinal medications in pregnancy. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:278–282. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yalaz M, Aydogdu S, Ozgenc F, Akisu M, Kultursay N, Yagci RV. Transient fetal myelosuppressive effect of D-penicillamine when used in pregnancy. Minerva Pediatr. 2003;55:625–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hanukoglu A, Curiel B, Berkowitz D, Levine A, Sack J, Lorberboym M. Hypothyroidism and dyshormonogenesis induced by D-penicillamine in children with Wilson’s disease and healthy infants born to a mother with Wilson’s disease. J Pediatr. 2008;153:864–866. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]