Abstract

The aim of this study is to estimate the extent to which children and adolescents with hearing impairment (HI) show higher rates of emotional and behavioural difficulties compared to normally hearing children. Studies of emotional and behavioural difficulties in children and adolescents were traced from computerized systematic searches supplemented, where appropriate, by studies referenced in previous narrative reviews. Effect sizes (Hedges’ g) were calculated for all studies. Meta-analyses were conducted on the weighted effect sizes obtained for studies adopting the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) and on the unweighted effect sizes for non-SDQ studies. 33 non-SDQ studies were identified in which emotional and behavioural difficulties in children with HI could be compared to normally hearing children. The unweighted average g for these studies was 0.36. The meta-analysis of the 12 SDQ studies gave estimated effect sizes of 0.23 (95 % CI 0.07, 0.40), 0.34 (95 % CI 0.19, 0.49) and −0.01 (95 % CI −0.32, 0.13) for Parent, Teacher and Self-ratings of Total Difficulties, respectively. The SDQ sub-scale showing consistent differences across raters between groups with HI and those with normal hearing was Peer Problems. Children and adolescents with HI have scores on emotional and behavioural difficulties measures about a quarter to a third of a standard deviation higher than hearing children. Children and adolescents with HI are in need of support to help their social relationships particularly with their peers.

Keywords: Hearing impairment, Emotional difficulties, Behavioural difficulties

Introduction

The mental health of children with hearing impairment (HI) is of potential concern as their social-emotional development may be negatively impacted by difficulties in communication. Co-occurring cognitive and physical impairments are additional risk factors for many children with HI. These mental health risks may also be exacerbated by experiences within families and within the education system [1–3]. For this reason it is important to determine if, and to what extent, their mental health is less good than that of hearing children so that intervention could be targeted at this possibly vulnerable group. Studies on this question have largely adopted questionnaire measures of emotional and behavioural difficulties (EBD) and there is a wide variation between studies in the prevalence of EBD found in children with HI.

A range of mental health problems have been found to be associated with HI including depression, aggression, oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder, and less consistently anxiety, somatization, and delinquency [4]. There is an unresolved issue of whether children with HI show hyperactivity and inattention. It has been suggested that children with HI may be prone to show increased rates of hyperactivity and ADHD symptomatology [5], but this is not a consistent finding across studies. Kelly et al. [6] reported an association between HI and ADHD in acquired HI cases only. Van Eldik [7] found that it was only children with HI and low intelligence that showed attention problems. Finally, the association between HI and ADHD reported by Hindley and Kroll [5] was only significant for school-based hyperactivity, and there was no significant effect relative to the general population on parents’ ratings of hyperactivity. Furthermore, some doubt was cast on the generalizability of this school-based finding by the suggestion that the effect may have arisen from the ratings of just one teacher [5].

In a narrative review of studies on EBD in children with HI, estimates varied between 0 and 77 % in the rates of EBD [8]. There are a number of possible reasons for these discrepancies between studies, including differences in the sampling of children with HI (e.g. age, the extent of other associated impairments, and the nature and severity of hearing loss), differences in the measure used and in the informant on behaviour (i.e. parent, teacher or child). Meta-analysis provides a transparent and replicable method for synthesizing the results of such disparate studies, for discerning the overall mean effect and for identifying studies that do not conform to this general pattern, i.e. outliers [9].

To date there has been no attempt to give a quantitative assessment of the magnitude of differences in the rates of EBD in general, or on specific types of behaviour difficulties, in children with and without HI. This paper will present the results of two quantitative reviews that we have undertaken of studies on EBD in children with HI. One is of studies using a variety of measures of behaviour difficulties. The second is of studies using the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [10]. We have analysed separately those studies that did or did not use the SDQ because the non-SDQ studies have varied widely in the instrument used, which may or may not have included subscales. By contrast the SDQ studies, being all based on the same measure, are more homogeneous and provide well-validated sub-scale scores, with equivalent ratings based on parent, teacher and self-report which can be analysed separately but in parallel. The adoption of this measure in a number of recent investigations allows a more definitive appraisal of not only just the overall extent of EBD in children with HI but also of the type of difficulties shown and whether these are equally apparent to parents and to teachers. There are, in addition, a small number of studies using self-ratings on the SDQ by older children and adolescents.

The comparison of the results of these two separate analyses has to be made circumspectly. There are a wide variety of measures used in the non-SDQ review and pooling of results from disparate measures must be treated with caution. The majority of these non-SDQ measures are nevertheless widely adopted in studies of child behaviour and have been well validated.

Method

Studies not using SDQ

Non-SDQ study inclusion

These were studies of EBD in children and adolescents with HI which did not use the SDQ as a measure. For inclusion, the studies need to provide information from validated questionnaires or interviews on the prevalence of EBD or mean problem scores in children with HI. In addition, data from a control group or norm data from population samples should have been provided. If such comparison data were not provided, studies were still included if such norm data could be obtained subsequently from elsewhere.

Non-SDQ study retrieval

The following databases were searched for studies published between 1970 and June 2014: Science Citation Index Expanded (1970–present), Social Sciences Citation Index (1970–present), Arts & Humanities Citation Index (1975–present), Conference Proceedings Citation Index—Science (1990–present), Conference Proceedings Citation Index—Social Science & Humanities (1990–present), MEDLINE, PUBMED and PSYCHInfo. The search terms were (1) child* or adolescent* AND (2) deaf* or hearing or PCHI or cochlear implant* or hearing aid AND (3) behaviour problems or mental health.

To ensure maximum coverage of this disparate literature, citations in two authoritative earlier reviews [8, 11] and a recently published systematic review [4] were also checked.

Non-SDQ study selection

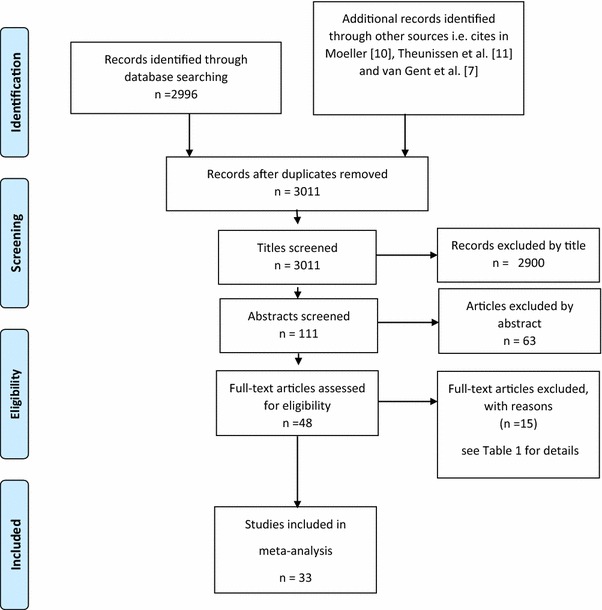

The search identified 48 papers that possibly could have been included but 15 of these studies did not meet the inclusion criteria. These papers and the reason for their exclusion are given in Table 1. From these various sources, there were therefore a total of 33 papers on non-SDQ EBD measures that met the inclusion criteria and details of these papers are given in Table 2. A summary of the selection of the non-SDQ studies is given in Fig. 1 in the form of a PRISMA flow chart [71].

Table 1.

Non-SDQ studies identified in the systematic search but excluded from the meta-analysis

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Aplin [12] | Data not able to be compared with hearing controls |

| Aplin [13] | Data not able to be compared with hearing controls |

| Barker et al. [14] | Data not able to be compared with hearing controls |

| Bat-Chava and Deignan [15] | Data not able to be compared with hearing controls |

| Bat-Chava, Martin and Kosciw [16] | Data not able to be compared with hearing controls |

| Bizjak [17] | Behaviour measured with instrument of uncertain equivalence to those used in other studies |

| Freeman, Malkin, and Hastings [18] | Data not able to be compared with hearing controls |

| Gallaudet research institute [19] | Data not able to be compared with hearing controls |

| Hindley et al. [6] | Data not able to be compared with hearing controls |

| Keilman, Limberger, and Mann [20] | Data not able to be compared with hearing controls |

| Kent [21] | Behaviour measured with instrument of uncertain equivalence to those used in other studies |

| King, Mulhall, and Gullone [22] | Behaviour measured with instrument of uncertain equivalence to those used in other studies |

| Kouwenberg et al. [23] | Behaviour measured with instrument of uncertain equivalence to those used in other studies |

| Maes and Grietens [24] | Data not able to be compared with hearing controls |

| Polat [25] | Data not able to be compared with hearing controls |

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies on EBD of children and adolescents with HI not using the SDQ

| Country | Nature of HI dB loss % Cochlear implant (CI) |

Age in years | Measure | % With mental health problems or Mean and SD on mental health measure |

Hedges’g | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hearing impaired group | Control or norm group | ||||||

| Anderssen et al. [26] | Sweden |

70 % severe or mild hearing loss in both ears 30 % severe or mild hearing loss in one ear |

7–12 | Rutter Parent Scalee | |||

| Internalizing | Mean = 1.95 | Mean = 1.84 | 0.16 | ||||

| SD = 0.88 | SD = 0.59 | ||||||

| N = 57 | N = 187 | ||||||

| Externalizing | Mean = 1.73 | Mean = 1.59 | 0.24 | ||||

| SD = 0.75 | SD = 0.52 | ||||||

| N = 57 | N = 187 | ||||||

| Rutter Teacher Scaleb | |||||||

| Internalizing | Mean = 2.04 | Mean = 1.81 | 0.28 | ||||

| SD = 0.89 | SD = 0.80 | ||||||

| N = 48 | N = 208 | ||||||

| Externalizing | Mean = 1.41 | Mean = 1.40 | 0.01 | ||||

| SD = 0.63 | SD = 0.70 | ||||||

| N = 48 | N = 208 | ||||||

| Arnold and Atkins [27] | England | Mean 66.7 dB loss | 4–11 | Bristol Social Adjustment Guidea | 44 % (n = 10/23) | 30 % (n = 7/23) | 0.30 |

| Rutter Teacher Scaleb | 0 % | 0 % | – | ||||

| Brubaker and Szakowski [28] | USA |

8 % 30–44 dB 13 % 45–59 dB 18 % 60–79 dB 61 % 80 + dB |

3–18 | Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory | |||

| Intensity scale | Mean = 104.15 | Mean = 91.43 | 0.52 | ||||

| SD = 25.86 | SD = 22.86 | ||||||

| N = 39 | N = 37 | ||||||

| Problem scale | Mean = 8.05 | Mean = 6.39 | 0.27 | ||||

| SD = 6.54 | SD = 5.90 | ||||||

| N = 39 | N = 37 | ||||||

| Cornes et al. [29] | Australia |

15 % severe 85 % profound |

11–18 | Youth Self Reportn | |||

| Internalizing | 17.9 % (n = 5/28) | 19.6 % (n = 250/1273) | −0.06 | ||||

| Externalizing | 25.0 % (n = 7/21) | 16.4 % (n = 209/1273) | 0.29 | ||||

| Davis et al. [30] | USA |

40 % < 44 dB 37.5 % 45–60 dB 22.5 % > 61 dB |

5–18 | Child Behavior Checklistc | |||

| Internalizing | Mean = 53.0 | Mean = 50.0h | 0.30 | ||||

| SD = 10.1 | SD = 10 | ||||||

| N = 40 | N = 300 | ||||||

| Externalizing | Mean = 54.2 | Mean = 50.0h | 0.42 | ||||

| SD = 10.4 | SD = 10 | ||||||

| N = 40 | N = 300 | ||||||

| Edwards et al. [31] | England | Profound pre-CI | 2–5 | CBCLg | |||

| Internalizing | Mean = 50.5 | Mean = 50.0h | 0.05 | ||||

| SD = 7.2 | SD = 10.0 | ||||||

| N = 17 | N = 300 | ||||||

| Externalizing | Mean = 51.2 | Mean = 50.0h | 0.12 | ||||

| SD = 8.3 | SD = 10.0 | ||||||

| N = 17 | N = 300 | ||||||

| Fundudis et al. [32] | England | Deaf not further specified | 7–10 | Rutter Teacher Scaleb | 44 % (n = 24/54)b | 18 % (n = 18/102)i | 0.72 |

| Furstenberg and Doyal [33] | USA |

80 % Serious or profound hearing loss in both ears |

11–21 | Teacher Report Formd | Average across grades | ||

| Internalizing | Mean = 53.71 | Mean = 50.0j | 0.38 | ||||

| SD = 8.73 | SD = 10 | ||||||

| N = 63 | N = 300 | ||||||

| Externalizing | Mean = 53.16 | Mean = 50.0j | 0.33 | ||||

| SD = 6.95 | SD = 10 | ||||||

| N = 63 | N = 300 | ||||||

| Hindley and Kroll [5] | England | >40 dB | 11–16 |

Rutter Parent Scalee Rutter Teacher Scaleb |

Hyperactive home | Hyperactive home | −0.15 |

| 9.9 % (n = 8/81) | 12.7 % (n = 63/498) | ||||||

| Hyperactive school | Hyperactive school | 0.48 | |||||

| 16.0 % (n = 13/81) | 7.2 % (n = 36/498) | ||||||

| Hyperactive pervasive | Hyperactive pervasive | 0.37 | |||||

| 8.6 % (n = 7/81) | 4.6 % (n = 23/498) | ||||||

| Kammerer [34] | Germany | >20 dB | 10–13 | Rutter Teacher Scaleb | 54 % (n = 99/183)b | 16 %i | 1.00 |

| Kelly et al. [6] | USA |

89 % Severe or greater loss |

4–21 | Conners’ Parent Rating Scalef | Females | Females | |

| Impulsive-hyperactive | Mean = 0.77 | Mean = 0.83 | −0.09 | ||||

| SD = 0.72 | SD = 0.61 | ||||||

| N = 97 | N = 238 | ||||||

| Impulsive-hyperactive | Males | Males | |||||

| Mean = 0.66 | Mean = 0.89 | −0.39 | |||||

| SD = 0.65 | SD = 0.59 | ||||||

| N = 115 | N = 291 | ||||||

| Hyperactivity | Females | Females | |||||

| Mean = 0.52 | Mean = 0.55 | −0.07 | |||||

| SD = 0.55 | SD = 0.39 | ||||||

| N = 97 | N = 238 | ||||||

| Hyperactivity | Males | Males | |||||

| Mean = 0.52 | Mean = 0.65 | −0.29 | |||||

| SD = 0.49 | SD = 0.44 | ||||||

| N = 115 | N = 291 | ||||||

| Konuk et al. [35] | Turkey |

3 % 56–70 db 8 % 71–90 db 89 % > 91 db |

6–18 | Child Behavior Checklistc | |||

| Internalizing | Mean = 57.84 | Mean = 52.11 | 0.50 | ||||

| SD = 11.78 | SD = 10.74 | ||||||

| N = 72 | N = 45 | ||||||

| Externalizing | Mean = 51.98 | Mean = 50.11 | 0.15 | ||||

| SD = 12.02 | SD = 12.24 | ||||||

| N = 72 | N = 45 | ||||||

| Kouwenberg et al. [36] | The Netherlands |

>40 dB 37 % CI |

8–15 | Child Depression Inventoryo | Mean = 1.39 | Mean = 1.33 | 0.29 |

| SD = 0.21 | SD = 0.20 | ||||||

| N = 78 | N = 130 | ||||||

| Li and Prevatt [37] | China | Deaf not further specified | 8–19 | Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scales | Females | Females | |

| Mean = 14.30 | Mean = 10.61 | 0.71 | |||||

| SD = 5.10 | SD = 5.08 | ||||||

| N = 30 | N = 34 | ||||||

| Males | Males | ||||||

| Mean = 15.55 | Mean = 11.18 | 1.08 | |||||

| SD = 3.36 | SD = 4.50 | ||||||

| N = 31 | N = 30 | ||||||

| Mitchell and Quittner [38] | USA |

53 % 70–100 dB 47 % > 100 dB |

6–14 | Child Behavior Checklistc | Mean = 58.0 | Mean = 50.0h | 0.79 |

| SD = 10.5 | SD = 10.0 | ||||||

| N = 39 | N = 300 | ||||||

| Teacher Report Formd | Mean = 56.8 | Mean = 50.0j | 0.71 | ||||

| SD = 5.2 | SD = 10.0 | ||||||

| N = 39 | N = 300 | ||||||

| Prior et al. [39] | Australia |

All aided 30–110 dB |

2–5 | Teacher rating PBQ | |||

| Total score | t = 3.72, df = 50 | 1.05q | |||||

| Quittner et al. [40] | USA | Severe to profound | Under 5 | CBCLn | |||

|

Total score Based on full information Imputed values |

Mean = 24.81 | Mean = 18.73 | 0.27 | ||||

| SD = 21.52 | SD = 14.29 | ||||||

| N = 181 | N = 92 | ||||||

| Remine and Brown [41] | Australia | Deaf not further specified | 6–18 | Child Behavior Checklistc | |||

| Internalizing | 16.9 % (11/65) | 13.3 % (433/3255) | 0.16 | ||||

| Externalizing | 13.8 % (9/65) | 12.7 % (413/3255) | 0.06 | ||||

| Youth Self-Reportn | |||||||

| Internalizing | 11.4 % (4/35) | 16.4 %(209/1273) | −0.23 | ||||

| Externalizing | 8.6 %(3/35) | 19.6 %(249/1273) | −0.53 | ||||

| Rutter, Graham, and Yule [42] | England | At least 40 dB loss | 5–14 | Interview and questionnaires | 15 % (n = 2/13)b | 7 % (n = 153/2189)i | 0.49 |

| Sahli, Arslan, and Belgin [43] | Turkey | 100 % with CI | 6–18 | Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scalet | |||

| Depressive emotioning | Mean = 3.02 | Mean = 2.30 | 0.67 | ||||

| SD = 1.68 | SD = 0.53 | ||||||

| N = 30 | N = 60 | ||||||

| Sinkkonen [44] | Finland | Deaf not further specified | 6–16 | Rutter Teacher Scaleb | 21 % (n = 62/294)b | 16 % (n = 37/234)i | 0.19 |

| Tharpe et al. [45] | USA | At least 80 dB loss 32 % with CI | 8–14 | Child Behavior Checklistc | Mean = 47.07k | Mean = 37.20 | 1.11 |

| SD = 6.80 | SD = 11.25 | ||||||

| N = 18 | N = 10 | ||||||

| Teacher Report Formd | Mean = 46.48k | Mean = 46.00 | 0.05 | ||||

| SD = 7.56 | SD = 11.25 | ||||||

| N = 17 | N = 8 | ||||||

| Theunissen et al. [46] | The Netherlands |

24 % 40–60 dB loss 28 % 61–90 dB loss 34 % > 90 dB loss 14 % Not known 33 % CI |

8–16 | Child Depression Inventoryo | Mean = 1.38 | Mean = 1.32 | 0.30 |

| SD = 0.21 | SD = 0.19 | ||||||

| N = 83 | N = 117 | ||||||

| Theunissen et al. [47] | The Netherlands |

26 % 40–60 dB loss 21 % 61–90 dB loss 53 % > 90 dB loss 14 % Not known |

9–16 | Child symptom inventoriesp | |||

| Generalized anxiety disorder | Mean = 1.50 | Mean = 1.36 | 0.35 | ||||

| SD = 0.46 | SD = 0.35 | ||||||

| N = 72 | N = 98 | ||||||

| Theunissen et al. [48] | The Netherlands |

24 % 40–60 dB loss 21 % 61–90 dB loss 49 % > 90 dB loss 7 % Not known |

8–16 | Child symptom inventoriesp | |||

| ADHD | t = 2.84 df = 192 | 0.41q | |||||

| ODD | t = 2.65 df = 192 | 0.38q | |||||

| CD | t = 3.30 df = 192 | 0.48q | |||||

| Topol et al. [49] | USA |

40 % Unilateral or < 40 dB loss 60 % > 40 dB loss |

1.5–2 | Child Behavior Checklist 1.5–5l | Mean = 45.9 | Mean = 43.5 | 0.26 |

| SD = 5.2 | SD = 10.3 | ||||||

| N = 30 | N = 91 | ||||||

| Van Eldik [50] | The Netherlands | +80 dB | 6–11 | CBCLc | |||

| Total score | t = 2.10, df = 493 | 0.19q | |||||

| Van Eldik et al. [7] | The Netherlands | >90 dB | 4–18 | Child Behavior Checklistc | 41 % (n = 98/238) | 16 % (n = 331/2068) | 0.72 |

| Van Eldik [51] | The Netherlands | >25 dB | 11–18 | Youth Self Reportg | 37 % (n = 75/202) | 17 % (n = 173/1016) | 0.58 |

| Van Gent et al. [8] | The Netherlands |

19 % 73–95 dB 81 % > 95 dB |

13–21 | Child Behavior Checklistc | 28 % (n = 16/58) | 16 % | 0.38 |

| Teacher Report Formd | 32 % (n = 22/68) | 17 % | 0.47 | ||||

| Vostanis et al. [2] | England | Severe to profound | 2–18 | Child Behavior Checklistc | 40 % (n = 29/73) | 8 %m | 1.11 |

| Wake et al. [52] | Australia |

22 % 20–40 dB 31 % 41–60 dB 17 % 61–80 dB 29 % > 80 dB |

7–8 | Child Behavior Checklistc | 36 % (n = 36/77) | 12 % (n = 24/198) | 1.02 |

| Teacher Report Formd | 20 % (n = 16/80) | 8 % (n = 7/86) | 0.58 | ||||

| Watt and Davis [53] | USA | >90 dB loss | Mean age = 13.7 years | Beck Depression Inventoryr | Mean = 10.52 | Mean = 6.62 | 0.66 |

| SD = 5.59 | SD = 6.13 | ||||||

| N = 50 | N = 30 | ||||||

aStott [54]

bRutter [55]

cAchenbach and Edelbrock [56]

dAchenbach and Edelbrock [57]

eRutter, Tizard and Whitmore [58]

fGoyette, Conners and Ulrich [59]

gAchenbach [60]

hBased on original standardization of CBCL

iTaken from van Gent et al. [8]

jBased on original standardization of TRF

kAverage of cochlear implant and hearing aid groups

lAchenbach [61]

mEstimated from normal curve distribution percentage with T score greater than 64

nAchenbach and Rescorla [62]

oKovacs [63]

pGadow and Sprakin [64]

q

rBeck et al. [65]

sReynolds and Richmond [66]

tRosenberg [67]

uEyberg and Ross [68]

vBehar and Springfield [69]

wSawyer et al. [70]

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart of selection of non-SDQ studies

Studies using SDQ

SDQ study inclusion

To be included the studies had to provide summary statistics on either a continuous scale (means and SD) or in categorical form (percentage with abnormal scores) for children or adolescents with HI on any of the Parent, Teacher or Self-rated versions of the SDQ. Each of these three versions of the SDQ gives an overall Total Difficulties score and five sub-scale scores for Emotional Symptoms, Conduct Problems, Hyperactivity, Peer Problems and Prosocial Behaviour. A positive effect size indicates lower Prosocial scores for children with HI than hearing controls but higher scores for children with HI on the other SDQ sub-scales and Total Difficulties. These scores could be compared either with a normally hearing control group or with population norms. The search was limited to published papers to ensure a level of methodological adequacy and rigour amongst those included and to avoid the inevitable problems with securing access to a full set of unpublished studies and the bias that this would introduce [72].

SDQ study retrieval

The following databases were searched for studies published between 1995 (when the SDQ was first published) and June 2014: Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Sciences Citation Index, Arts & Humanities Citation Index, Conference Proceedings Citation Index—Science, Conference Proceedings Citation Index—Social Science & Humanities, MEDLINE, PUBMED and PSYCHInfo. The search terms were (1) measure: SDQ or Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, AND (2) Participants: deaf* or Hearing or PCHI or Cochlear implant* or Hearing aid.

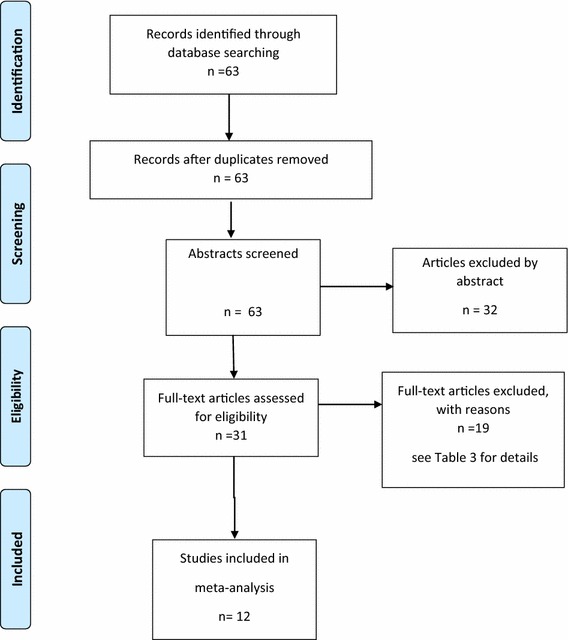

SDQ study selection

The search identified 31 possible studies for inclusion. Of these 19 failed to meet the criteria above for study inclusion. The reasons for exclusion of these 19 studies are summarized in Table 3. The details of the 12 studies included in the analysis are presented in Table 4. The study selection was made independently by two of the authors (JS and HP). In the case of disagreements adjudication was made by a third author (CK). There were two studies where there was uncertainty over their inclusion. One was a study of children with Usher syndrome with complex disabilities in addition to hearing loss [73]. An additional issue with this paper was that SDQ scores were not reported for six children with diagnosed “mental or behavioural disorder”. The second paper [74] studied children with HI associated with a persistent or recurrent history of middle ear disease. It was decided to include both these studies but to conduct a sensitivity analysis to determine if their exclusion modified the results materially. The data extraction was undertaken by JS and the accuracy of data extraction from the papers was determined by a second author (HP) independently checking the summary statistics used to derive the effect sizes for each study. A summary of the selection process for the SDQ studies is given in Fig. 2.

Table 3.

SDQ studies identified in the systematic search but excluded from the meta-analysis

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Fellinger et al. [75] | Sub-set of participants reported in Fellinger et al. [99] |

| Fellinger et al. [76] | Same participants as in Fellinger et al. [99] |

| Fellinger and Holzinger [77] | Not peer reviewed |

| Garg et al. [78] | No report of findings by hearing loss, although neurofibromatosis type 2 is associated with hearing loss |

| Gurney et al. [79] | Did not use the SDQ |

| Hintermair [80] | Duplicate of data in Hintermair [101] |

| Hintermair [81] | Did not provide means and SDs |

| Hutchison and Gordon [82] | Not only children with HI |

| Ketelaar et al. [83] | Non-standard use of sub-set of SDQ items |

| Marret et al. [84] | Not only children with HI |

| McCormack et al. [85] | Not only children with HI |

| Moller [86] | Adults with complex disabilities |

| Muigg, Nekahm-Heis, and Juen [87] | Did not provide means and SDs |

| Rieffe, Ketelaar, and Wiefferink [88] | Not on children with HI |

| Saigal et al. [89] | Not just children with HI |

| St Clair et al. [90] | Not just children with HI |

| Stevenson et al. [1] | Same sample as Stevenson et al. [107] |

| Sumpter et al. [91] | Not just children with HI |

| Watson and Brown [92] | No new data—editorial |

Table 4.

Characteristics of studies on EBD in children and adolescents with HI using the SDQ

| Study | Country | No. of hearing impaired | Nature of HI % Cochlear implant (CI) |

Age HI in years | SDQ ratingsa | Hearing controls | Other comparison used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anmyr et al. [93] | Sweden | 22 |

41-69 dB loss 5 % 70-94 dB loss 14 % >95 dB loss 81 % CI 100 % |

9–15 | P, T, S | None | Meltzer et al. [94] |

| Cornes and Brown [95] | Australia | 54 |

>90 dB CI 18.5 % |

11–18 | P, T, S | None | Used Goodman [96] UK norms |

| Dammeyer [97] | Denmark | 334 |

>80 dB loss 36 %, <80 dB loss 36 %, CI 28 % |

6–19 | T | None | Used Smedje et al. [98]. Swedish hearing sample |

| Dammeyer [73] | Denmark | 17 | Hearing loss confirmed by standard hearing tests completed by a clinical audiologist | 3–17 | T | None | Used Smedje et al. [98] Swedish hearing sample |

| Fellinger et al. [99] | Austria | 99 |

Bilateral hearing loss of at least 40 dB CI 20.9 % |

6:5–16 | P, T | None |

Used norms from Germany Worner, et al. [100] and British SDQ standardization samples Meltzer et al. [94] |

| Hintermair [101] | Germany | 213 |

< 70 dB 38 % 70–90 dB 35 % > 90 dB 27 % CI 23.5 % |

4–12 | P | None | Used existing German norms for the SDQ, Woerner et al. [100] |

| Hogan et al. [102] | Australia |

Cohort B 26 |

“Hearing problems” reported by parents | Cohort B 5.5 yearsb | P |

Cohort B Approx. 4000 normal-hearing children |

Not applicable |

|

Cohort K 93 |

Cohort K 7.5 yearsb | P |

Cohort K Approx. 4000 normal-hearing children |

||||

| Huber and Kipman [103] | Austria | 35 |

“Profound” bilateral hearing loss CI 100 % |

12–17 | P, T, S | 212 normal-hearing adolescent peers (mean age 15.0, ranging from 12.3 to 17.9 years) | Not applicable |

| Mejstad et al. [104] | Sweden | 111 |

Children who had been prescribed hearing aids CI 3.3 % |

11–18 | P, T, Sc | None | The scale means found in comparable Nordic countries such as Norway (Van Roy et al. [105]) and Finland (Koskelainen et al. [106]) |

| Stevenson et al. [107]c | UK | 107 |

Moderate 40–69 dB loss 54 % Severe 70–94 dB loss 24 % Profound > 95 dB loss 22 % CI 13.6 % |

5:5–11:8 | P, Td | Comparison group of 63 children with normal hearing aged 6:4 to 9:10, born at the same hospitals as those with PCHI | Not applicable |

| Timmerman et al. [74] | The Netherlands | 160 |

Children with a disease history of persistent or recurrent middle ear disease and suffering from either upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) and/or otitis media with effusion OME on the day of assessment The average bilateral hearing level found was 20.0 dB (S.D. = 11.5 dB, range 1.3–49.4 dB) CI 0 % |

4–7 | P | None | A community sample of US children participating in the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) conducted by the National Centre for Health Statistics, was used for comparison (Simpson et al. [108]) |

| Vetter et al. [109] | Germany | 57 |

Degree of loss Mild 9 % Moderate 14 % High 40 % Residual hearing 37 % NB dB levels not specified CI 33 % |

6:11–12:7 | Tc | None | None |

a P parent, T teacher, S self

bThis is a longitudinal study with behaviour measured at various waves. The effect sizes were calculated using the average of the adjusted odds ratios across these waves and these ages are the mean of the age ranges concerned

cMeans and SDs were calculated for all participants pooled together

dMeans and SDs were calculated by the authors for all participants using the raw data

Fig. 2.

PRISMA flow chart of selection of SDQ studies

Data for normally hearing comparison groups

The studies may have no controls, their own control group or use a large general population sample for comparison purposes. There is a range of such general population samples that can provide norms for the SDQ. Different studies use different samples for normative comparisons. The use of these general population samples for comparison creates a severe distortion to the standard error of the Hedges’ g estimate. The sample sizes are of the order of 100 times the size of that for the studies using control groups. The random effects meta-analysis consequently gives these studies a much greater weight than those using their own controls. To overcome this distortion and to allow the inclusion of studies presenting no comparison data, the effect sizes for the impact of HI on SDQ scores were calculated using a common population sample to provide comparison data for all the studies. The norms provided by Meltzer et al. [94] were selected as these were based on a large British general population sample with norms available for parents (N = 10,298) and teachers (N = 8208) and for self-ratings for older children (N = 4228). For this sample norms are provided for two age ranges (5–10 years and 11–15 years). This therefore allows a limited adjustment for age effects to be achieved. For each study, the mean and SD for the age group norms closest in age to the hearing impaired sample was used for comparison. For those studies reporting only the percentage extreme scorers in the hearing impaired group, the appropriate percentage in the age-matched normative sample was used. These comparisons between children with HI and the general population sample could be made for Parent, Teacher and Self-ratings on the Total Difficulties score, for each of four problem sub-scales and for the Prosocial sub-scale.

Calculating effect sizes

For both SDQ and non-SDQ studies, the effect size used was Hedges’ g which provides a standardized mean difference in scores between children with HI and those with normal hearing as follows:

where N = N HI + N Controls and

For studies using a categorical scoring, the log odds ratio was calculated and converted to d and then to g using the methods on p. 47 and p. 2 [9]. In all cases, a positive effect size indicates a higher EBD score for children with HI compared to normally hearing children.

The 32 studies not using the SDQ applied a range of methods of measuring behaviour in children with HI (see Table 2). In addition, these studies used various sources for data on the mental health of normally hearing children, i.e. study-specific control groups and population norms. A meta-analysis usually involves averaging the Hedges’ g using a weighting procedure that reflects the confidence in the value of g—studies with a smaller standard error, usually associated with larger N, get greater weight. We did not do this for non-SDQ studies because of concerns over the heterogeneity in the range of measures used in the studies, the variation in control and norm groups used as comparators and because the effect size was based on means in some cases and percentage of extreme scorers in others. Instead the unweighted average value of Hedges’ g is reported (see [110] for a discussion of this approach). In addition to the average effect size for overall behaviour difficulties for these non-SDQ studies, the average effect sizes for internalizing and externalizing behaviours are also presented. The parent-rated child behavior checklist (CBCL) [56] total problem scores were the non-SDQ measure most frequently reported and an average effect size was calculated for these studies also.

In the case of SDQ studies, the above considerations were not relevant and weighted Hedges’ g was used to provide a standardized mean difference between children with and without HI for each study. These values were used to undertake a meta-analysis using the metan command in Stata [111]. The estimate of the overall effect size was obtained using a random effects model, as the effect sizes in these studies were thought unlikely to be functionally equivalent given that different samples were being studied by different research groups in different countries. For the SDQ studies, a test was made to examine whether the magnitude of differences in behaviour between children with HI and controls changed with age. Meta-regressions were conducted using the metareg command in Stata [112] with Hedges’ g as the dependent and age the independent variable.

To provide “a like for like” comparison between SDQ and non-SDQ studies, we also report the unweighted Hedges’ g for SDQ studies.

Results

Studies not using SDQ

The 33 non-SDQ studies provided 57 estimates for the standardized mean difference (g) of EBD scores for children with HI and hearing controls or a norm group (see Table 2). The unweighted mean effect size was 0.36 (95 % CI 0.26, 0.46; range −0.53 to 1.11). There were 31 estimates based on Parent reports of behaviour with a mean value of 0.34 (95 %CI 0.21, 0.47; range −0.39 to 1.11). The 17 Teacher rating-based estimates gave a higher mean value of 0.46 (95 % CI 0.28, 0.64; range 0.01 to 1.05). These estimates were a mix of effect sizes derived from continuous and categorical measures of EBD. The mean effect size for the 21 categorical measures was slightly higher (0.38, 95 % CI 0.21, 0.54; range −0.39 to 1.11) than that for the 36 continuous indicators (0.35, 95 % CI 0.23, 0.47; range −0.39 to 1.11). When estimates for internalizing and externalizing symptoms were available, a higher mean value of g was obtained for internalizing symptoms (0.35, 95 % CI 0.19, 0.51; range −0.23 to 1.08) than for externalizing behaviours (0.12, 95 % CI −0.03, 0.26; range −0.53 to 0.48). The highest effect size was obtained for total behaviour scores (0.58, 95 % CI 0.44, 0.72; range 0.05 to 1.11). Of these effect sizes for total behaviour problems five were obtained from continuous scores on the CBCL rated by parents and provided an effect size of 0.52 (95 % CI 0.13, 0.92). There are four studies in Table 2 that were not published in peer-reviewed journals. When these were excluded the unweighted mean effect size was reduced slightly to 0.34 (95 % CI 0.24, 0.45; range −0.53 to 1.11).

Studies using SDQ

There were 12 SDQ studies which provided 10 Parent, 9 Teacher and 4 Self-rated estimates of effect size for Total Difficulties. There were 10, 6 and 4 estimates available for the SDQ sub-scales for Parents, Teacher and Self-rated scores, respectively. One study provided data on two cohorts each of which had SDQ assessment by parents on multiple occasions [102]. The average percentage of high scorers across the assessment’s multiple pre-specified time points was entered into the meta-analysis separately for each cohort.

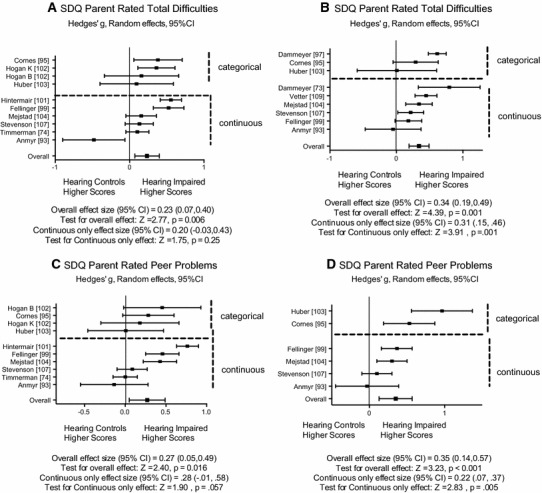

The random effects model estimates of effect size are presented in Table 5. There is a significant effect size for Parent (0.23) and Teacher (0.34) ratings of Total Difficulties but not for Self-rated scores (−0.01), respectively. The heterogeneity indices based on χ 2 are significant for Parent and Teacher ratings. The high values of I 2 suggest that there are systematic rather than random differences between the estimates from the studies. A larger set of studies would be needed to explore the reason for this heterogeneity using meta-regression.

Table 5.

Effect sizes (Hedge’s g) for SDQ sub-scales rated by parents, teachers and self using random effects estimates for the studies overall and for studies with continuous measures

| No. of studies | Overall | Overall heterogeneity | Continuous only | Continuous heterogeneity | Ma | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g | 95 % CI | Z | P | χ 2 | Df | P | I 2 | g | 95 % CI | Z | P | χ 2 | Df | P | I 2 | g | ||

| Total difficulties | ||||||||||||||||||

| Parent | 10 | 0.23 | 0.07, 0.40 | 2.77 | 0.006 | 42.27 | 9 | 0.001 | 78 | 0.20 | −0.03, 0.43 | 1.75 | 0.080 | 40.77 | 5 | 0.001 | 88 | 0.20 |

| Teacher | 9 | 0.34 | 0.19, 0.49 | 4.39 | 0.001 | 28.08 | 8 | 0.001 | 72 | 0.31 | 0.15, 0.46 | 3.91 | 0.001 | 12.50 | 5 | 0.001 | 60 | 0.31 |

| Self-rated | 4 | −0.01 | −0.32, 0.13 | 0.85 | 0.397 | 3.78 | 3 | 0.287 | 21 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | −0.23 |

| Emotional symptoms | ||||||||||||||||||

| Parent | 10 | 0.21 | 0.08, 0.32 | 3.43 | 0.001 | 29.60 | 9 | 0.001 | 70 | 0.22 | 0.07, 0.37 | 2.80 | 0.005 | 27.82 | 5 | 0.001 | 99 | 0.16 |

| Teacher | 6 | 0.14 | −0.03, 0.30 | 1.62 | 0.106 | 14.22 | 5 | 0.014 | 94 | 0.15 | −0.04, 0.34 | 1.49 | 0.135 | 12.76 | 3 | 0.005 | 98 | −0.02 |

| Self | 4 | 0.19 | −0.18, 0.40 | 0.74 | 0.456 | 59.58 | 3 | 0.001 | 95 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.05 |

| Conduct problems | ||||||||||||||||||

| Parent | 10 | 0.16 | −0.03, 0.35 | 1.65 | 0.100 | 61.72 | 9 | 0.001 | 99 | 0.12 | −14, 0.39 | 0.90 | 0.366 | 58.54 | 5 | 0.001 | 92 | 0.14 |

| Teacher | 6 | 0.22 | 0.10, 0.34 | 3.62 | 0.001 | 5.86 | 5 | 0.001 | 94 | 0.23 | 0.11, 0.34 | 3.76 | 0.001 | 3.29 | 3 | 0.349 | 8 | 0.06 |

| Self | 4 | −0.25 | −0.53, 0.03 | 1.74 | 0.082 | 6.66 | 3 | 0.001 | 96 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | −0.25 |

| Hyperactivity | ||||||||||||||||||

| Parent | 10 | 0.05 | −0.06, 0.16 | 0.91 | 0.363 | 16.26 | 9 | 0.062 | 45 | 0.09 | −0.02, 0.20 | 1.56 | 0.119 | 10.14 | 5 | 0.071 | 50 | −0.07 |

| Teacher | 6 | 0.03 | −0.16, 0.22 | 0.34 | 0.735 | 11.58 | 5 | 0.041 | 57 | 0.07 | −0.12, 0.27 | 0.73 | 0.464 | 8.32 | 3 | 0.040 | 64 | −0.17 |

| Self | 4 | −0.21 | −0.38, −0.04 | 2.44 | 0.015 | 1.09 | 3 | 0.780 | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | −0.27 |

| Peer problems | ||||||||||||||||||

| Parent | 10 | 0.27 | 0.05, 0.49 | 2.40 | 0.016 | 72.71 | 9 | 0.001 | 88 | 0.28 | −0.01, 0.58 | 1.90 | 0.057 | 69.83 | 5 | 0.001 | 93 | 0.22 |

| Teacher | 6 | 0.35 | 0.14, 0.57 | 3.23 | 0.001 | 19.09 | 5 | 0.002 | 74 | 0.22 | 0.07, 0.37 | 2.83 | 0.005 | 5.18 | 3 | 0.159 | 42 | 0.37 |

| Self | 4 | 0.41 | 0.24, 0.58 | 4.79 | 0.001 | 0.91 | 3 | 0.823 | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.43 |

| Prosocial behaviour | ||||||||||||||||||

| Parent | 10 | 0.30 | 0.08, 0.52 | 2.61 | 0.009 | 107.41 | 9 | 0.001 | 92 | 0.24 | −0.01, 0.49 | 1.87 | 0.062 | 84.62 | 5 | 0.001 | 85 | 0.25 |

| Teacher | 6 | −0.10 | −0.31, 0.12 | 0.88 | 0.376 | 17.14 | 5 | 0.004 | 71 | −0.07 | −0.34, 0.20 | 0.52 | 0.605 | 15.44 | 3 | 0.001 | 81 | −0.15 |

| Self | 4 | −0.00 | −0.33, 0.33 | 0.01 | 0.990 | 6.82 | 3 | 0.078 | 56 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.04 |

aMean of unweighted effect sizes—Hedge’s g

The results for Self-rated estimates have to be treated cautiously as these are based on just four studies. There is a pattern whereby the children and adolescents rate themselves as having fewer difficulties than those reported by Parents and Teachers. The exception is Peer Problems where the Self-rated score gives the highest effect size of all (0.41).

Forest plots of the effect sizes for Parent and for Teacher Total Difficulties scores are presented in Fig. 3A and B. There are too few studies with self-rated scores to warrant presentation. A somewhat surprising finding is that of Anmyr et al. [93] which is the only study to produce a significant effect size that shows children with HI have lower Total Difficulties score than hearing controls, but this is found for Parent ratings only.

Fig. 3.

Forest plots for SDQ Total Difficulties and Peer Problems rated by Parents and by Teachers differentiating studies using categorical and continuous scoring. Effect sizes are Hedges’ g with 95 % confidence intervals estimated using a random effects model

Only the SDQ Peer Problem sub-scale shows a consistent pattern of more difficulties for children with HI. The estimate is significant for Parent, Teacher and Self-rated scores (effect size of 0.27, 0.35 and 0.41, respectively). The effect sizes for Parent and Teacher scores for Peer Problems for individual studies are shown in Fig. 3C and D.

Meta-regression for age

To test whether the effect size changed with age, meta-regressions were conducted for all scales for all raters. In 14 of these 18 regressions the effect size declined with age but only in the case of Self-ratings on the Emotional Symptoms scale did this reach significance (coefficient = −0.14, SE = 0.02, P < 0.02).

Sensitivity analyses

The effect sizes presented above are based on both categorical and continuous measures of EBD. A sensitivity analysis was carried out on Parent and Teacher ratings to establish whether restricting the meta-analysis to continuous-only measures changed the pattern of results. This was not possible for Self-rated measures as there were too few values. The effect sizes based on continuous measures alone are presented in Table 5. The pattern of results remains largely unchanged.

The effect of removing the two studies where inclusion was uncertain was that the effect size for Parent Total Difficulties was little changed (0.25) and for Teacher Total Difficulties fell from 0.34 to 0.31 and in both cases the effect remained significant.

Comparing the non-SDQ and SDQ study effect sizes

The methods of summarizing effect sizes described so far for the SDQ studies are different from those reported above for the non-SDQ studies. To allow a more appropriate comparison to be made, Table 5 includes in the final column a value for the unweighted mean effect size; the same summary as was given for the non-SDQ studies in Table 2. As reported above, the unweighted mean for the non-SDQ studies was 0.34 for Parent and 0.46 for Teacher ratings. For the SDQ studies, Total Difficulties means were somewhat lower at 0.20 for Parents and 0.31 for Teachers. This comparison must be treated with caution as the non-SDQ effect sizes are based on pooling of results from a wide variety of measures of EBD.

Discussion

The analyses presented in this paper suggest that children and adolescents up to age 21 years with HI are likely to show an elevated rate of EBD. As rated on the SDQ by Parents and by Teachers (but not by the children themselves), these children and adolescents show an overall EBD score 0.23 of a SD above that of normally hearing children. The effect is more substantial for teacher ratings (0.34). There is an indication that this effect may decline with age but more studies (preferably longitudinal) are needed to adequately test for age-related changes. This pattern of a greater effect in teacher ratings is also found in the non-SDQ studies. In these studies, the effect sizes are slightly larger: namely 0.34 and 0.46 for Parent and Teacher ratings, respectively.

The findings from the SDQ studies suggest that Peer Problems showed the most marked and consistent increased risk of EBD. For Teacher ratings only, a significantly higher mean Conduct Problems score was obtained for children with HI. For Parent ratings only, there was a significant association between HI and elevated Emotional Symptoms. For all raters, there was no evidence that children with HI showed elevated levels of Hyperactivity. Parents report significantly less Prosocial Behaviour in children with HI.

The lower estimate of effect size in the SDQ studies might arise from a number of factors. First, the methods of measuring EBD might have an impact, e.g. in terms of the number and types of behaviour items included. Second, the adoption of a common large general population sample to provide an SDQ behaviour score for hearing children may also have reduced the effect size. In the non-SDQ studies, some of the control group scores are “super-normal”, i.e. unexpectedly low (e.g. [45]) and therefore might inflate the effect size estimate. Third, a number of the non-SDQ studies were published much earlier than the SDQ studies, all of which were published after the year 2000. Consequently, a smaller effect size may reflect improvements in the provision for psychological support for children with HI or changes in educational provision and policy which resulted in fewer difficulties being reported in the later studies. Children in these SDQ studies may also have benefited from early detection and confirmation of hearing loss as a result of universal newborn hearing screening. Since such screening and early confirmation are associated with better language [113] and better language is associated with reduced EBD [1], this could have led to a reduction in EBD in more recent studies. However, a direct test of the effect of early confirmation on later behaviour failed to detect a benefit [107] perhaps because the associated improvement in language was only to a rather low level, e.g. mean aggregate receptive language z score in children with early confirmed hearing impairments remained 1.76 SD below the mean score in the normally hearing comparison group.

The findings of Anmyr et al. [93] are a clear exception to the general pattern of the SDQ results. In that study the children with HI are rated as showing fewer EBD than controls. A distinctive feature of the sample in [93] was that all the children had received cochlear implants. The other study exclusively including children with cochlear implants was that by Huber and Kipman [103]. They too found no difference in parental ratings on the SDQ, although teachers in that study did report significantly more Peer Problems in the cochlear implant group compared to controls. The remainder of the SDQ studies had fewer than 33 % of cases receiving cochlear implants. It remains unclear whether those treated with cochlear implants may have fewer EBD or whether specific cultural factors such as parental expectations about behaviour may have resulted in the anomalous findings reported in [93], as these authors suggest.

Hyperactivity

Our findings suggest no heightened risk for children with HI to present with symptoms of hyperactivity or inattention. This was somewhat surprising considering that there is some evidence for a possible link between HI and ADHD-type symptoms related to underlying cognitive abilities. Specifically, it has been shown that children with HI are more likely to have deficits in executive function and that scores on executive function were significantly related to Total Difficulties scores on the SDQ [81]. As attention and executive abilities are thought to be aspects of the underlying cognitive difficulties experienced by children with ADHD (see [114] and [115], respectively), it might be expected that children with HI would be likely to show a pattern of behaviour similar to ADHD.

However, evidence from studies using visually presented material to examine attention in HI participants is inconsistent. Tharpe et al. [45] found few differences between children with and without HI in visual attention performance. They suggested that the effects are influenced both by age and intelligence and differences between the groups disappeared when these factors were controlled statistically. By contrast, Mitchell and Quittner [38] reported significant attention deficits in children with HI on two of three attention tasks using the continuous performance test (CPT [116]). Performance on the CPT tasks was significantly associated with Parent and Teacher ratings of behaviour difficulties. However, the authors concluded that the attention problems in children with HI were not necessarily related to ADHD. Instead, they suggested that children with HI show a distinct pattern of impaired attention and problem behaviours. Furthermore, Quittner et al. [117] showed how the development of this pattern of impaired attention can be at least partially off-set by cochlear implantation. This was consistent with other evidence [118] which suggested that visual attention improves when children with HI are given cochlear implants.

There is no indication from the SDQ studies reviewed here that children with HI have a specific propensity to develop hyperactivity. Indeed the effect sizes for parent and teacher ratings are non-significant and for Self-ratings are in the opposite direction. This raises the question of why overviews of the earlier studies on children with HI have concluded that hyperactivity was a particularly salient feature of their behaviour.

There is a possibility that the SDQ is a less valid or less sensitive measure of hyperactivity or ADHD as it only relies on five items to assess this pattern of behaviour. However, studies of large general population samples in Europe [119] and in the USA [120] and of clinical samples of children with ADHD [121, 122] have supported the validity of the SDQ as a measure of hyperactivity. A summary of such data is given in a meta-analysis of 48 studies (N = 131,223) on the psychometric properties of the SDQ [123].

It appears then that earlier studies of ADHD-related behaviours in children with HI may have over-estimated such an association possibly as a result of the difficulties that have been noted in the assessment of such behaviour in deaf children, such as failure to follow directions being the consequence of hearing impairment rather than inattention [124].

Mediating and risk factors

It is important to note that the present meta-analysis does not directly examine the possible factors mediating the impact of HI on EBD but these need to be considered in interpreting the findings. It has been suggested that low non-verbal IQ [3, 45] and language impairment may be crucial mediators [5, 6]. The difficulties in language acquisition experienced by children with HI may contribute to the risk of EBD in a number of ways. The first is via a failure to effectively understand or communicate information about needs and wants with others. The second is via deficits in emotional and behavioural regulation that are, in part, dependent on language processing. These are interpersonal and intrapersonal processes respectively and children with HI may have deficits in either or both of these with consequently adverse effects on behaviour [14]. It has also been suggested that the language deficits in children with HI are related to intrapersonal cognitive processes such as attention [125] and executive function [126] that in turn create a vulnerability to poor behavioural regulation.

The optimal method for detecting risk factors, i.e. features that make a child with HI more likely to develop EBD, is via a multiple regression moderator analysis based on the child as the unit of analysis [127]. The present meta-analysis only has the study as the unit of analysis and using a meta-regression tested whether age was a moderator of the effect of HI on EBD. It was not. The approach adopted by Theunissen [4] was to survey whether specific risk and protective factors had been found to relate to EBD within HI samples. Using this approach, age at detection and intervention of hearing loss, the presence of additional disabilities, communication skills, intelligence, type of school, and number of siblings were suggested as possible influences on EBD in children and adolescents with HI.

Peer problems

The review of the studies using the SDQ identifies Peer Problems as the area with the most difficulties for children with HI. Other studies reinforce this notion of peer relationships and friendships as being problematic for children with HI. Henggeler et al. [128] found that the mothers and the fathers of adolescents with HI, but not the adolescents themselves, rated their relationship with friends as showing more aggression than did the parents of hearing adolescents. Parents reported that their deaf children were socially isolated and did not participate in structured activities [2]. This effect was found for otherwise well-functioning children and not just for those with behaviour problems. A school-based study also reported that although not rejected by others, deaf pupils in mainstream schools may feel isolated [129]. As a result, they show lower self-esteem in relation to peer relationships [130]. One factor likely to be contributing to peer relationship difficulties is the delay in acquiring pragmatic language skills shown by children with HI [131].

There is some evidence that social skill training can have an enduring beneficial effect on peer relationships in deaf children [132]. Replication and extension of these findings on intervention are clearly needed as the findings in this review suggest that peer relationship problems may be a real risk for children with HI. Further research is necessary to illuminate the processes by which children with HI become more socially isolated; in particular into the role, difficulties in language ability are likely to play as a mediator in this association. The clinical and service implications of social and mental health problems in deaf children and adults have been recently reviewed [133].

Limitations on the study

As discussed above a major feature of the studies being reviewed was their heterogeneity in terms of factors such as age, severity of hearing loss, numbers of children with cochlear implants and types of control/comparison groups employed. There were also a wide range of methods used to measure EBD. This in part was addressed by separating studies applying the SDQ from those using other questionnaires. It is feature of all the studies reported here that they were reliant on partner, teacher or self-ratings on questionnaires to obtain assessment of EBD. It is uncertain what affect the absence of more clinically sensitive methods this might have on the level of EBD found in children with HI [134].

Conclusions

The analyses presented here confirm that children with HI are more likely to show EBD than other children. The effect may be less marked than earlier studies suggested. The ratings of EBD by teachers show the largest effect. There is no indication that HI is related to hyperactivity or ADHD-related behaviours. It is in the area of peer relationships that the most marked behaviour difficulties for children with HI are found.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Maria Huber and Dr. Florian Juen for answering queries concerning their studies. We gratefully acknowledge the support of The Wellcome Trust that made this study possible. We thank also members of the Hearing Outcomes in Teenagers steering group for their advice; Hazel Blythe, Merle Mahon, Janet Peacock, Steve Powers, Emmanouela Terlektsi, Brian Yuen. The work reported here was undertaken as part of a study supported by The Wellcome Trust Grant Number 089251/Z/09/Z.

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Stevenson J, McCann D, Watkin P, Worsfold S, Kennedy C, Hearing Outcomes Study Team The relationship between language development and behaviour problems in children with hearing loss. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51:77–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vostanis P, Hayes M, Du Feu M, Warren J. Detection of behavioural and emotional problems in deaf children and adolescents: comparison of two rating scales. Child Care Health Dev. 1997;23:233–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.1997.tb00966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hindley PA, Hill PD, McGuigan S, Kitson N. Psychiatric disorder in deaf and hearing impaired children and young people: a prevalence study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1994;35:917–9344. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb02302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Theunissen SCPM, et al. Psychopathology and its risk and protective factors in hearing-impaired children and adolescents a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:170–177. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.3974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hindley P, Kroll L. Theoretical and epidemiological aspects of attention deficit and overactivity in deaf children. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 1998;3:64–72. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.deafed.a014341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly D, Kelly B, Jones M, Moulton N, Verhulst S, Bell S. Attention deficits in children and adolescents with hearing loss. Am J Dis Child. 1993;147:737–741. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1993.02160310039014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Eldik TT, Treffers PDA, Veerman JW, Verhulst FC. Mental health problems of deaf Dutch children as indicated by parents’ responses to the child behavior checklist. Am Ann Deaf. 2004;148:390–395. doi: 10.1353/aad.2004.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Gent T, Goedhart AW, Hindley PA, Treffers PDA. Prevalence and correlates of psychopathology in a sample of deaf adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:950–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38:581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moeller MP. Current state of knowledge: psychosocial development in children with hearing impairment. Ear Hear. 2007;28:729–739. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e318157f033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aplin DY. Social and emotional adjustments of hearing-impaired children in special schools. J Br Assoc Teach Deaf. 1985;9:84–94. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aplin DY. Social and emotional adjustments of hearing-impaired children in ordinary and special schools. Educ Res. 1987;29:56–64. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barker DH, et al. Predicting behavior problems in deaf and hearing children: the influences of language, attention, and parent–child communication. Dev Psychopathol. 2009;21:373–392. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bat-Chava Y, Deignan E. Peer relationships of children with cochlear implants. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2001;6:186–199. doi: 10.1093/deafed/6.3.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bat-Chava Y, Martin D, Kosciw JG. Longitudinal improvements in communication and socialization of deaf children with cochlear implants and hearing aids: evidence from parental reports. J Child Psychol Psychiaty. 2005;46:1287–1296. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bizjak MC. Understanding emotional health and psychological adjustment in students with or without a specific hearing deficiency. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2009;21:213–224. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freeman RD, Malkin SF, Hastings JO. Psychosocial problems of deaf children and their families: a comparative study. Am Ann Deaf. 1975;120:275–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallaudet Research Institute . Regional and national summary report of data from the 2007–08 Annual Survey of Deaf and Hard of Hearing Children and Youth. Washington, DC: Gallaudet Research Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keilmann A, Limberger A, Mann WJ. Psychological and physical well-being in hearing-impaired children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71:1747–1752. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kent BA. Identity issues for hard-of-hearing adolescents aged 11, 13, and 15 in mainstream setting. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2003;8:315–324. doi: 10.1093/deafed/eng017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King NJ, Mulhall J, Gullone E. Fears in hearing-impaired and normally hearing children and adolescents. Behav Res Ther. 1989;27:577–580. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(89)90094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kouwenberg M, Rieffe C, Theunissen SCPM, Oosterveld P. Pathways underlying somatic complaints in children and adolescents who are deaf or hard of hearing. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2012;17:319–332. doi: 10.1093/deafed/enr050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maes B, Grietens H. Parent-reported problem behaviour among children with sensory disabilities attending elementary regular schools. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2004;16:361–375. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polat F. Factors affecting psychosocial adjustment of deaf students. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2003;8:325–339. doi: 10.1093/deafed/eng018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andersson G, Olsson E, Rydell A-M, Larsen HC. Social competence and behaviour problems in children with hearing impairment. Audiology. 2000;39:88–92. doi: 10.3109/00206090009073058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnold P, Atkins J. The social and emotional adjustment of primary hearing-impaired children integrated in primary schools. Educ Res. 1991;33:223–228. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brubaker RG, Szakowski A. Parenting practices and behavior problems among deaf children. Child Fam Behav Ther. 2000;22:13–28. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cornes A, Rohan MJ, Napier J, Rey JM. Reading the signs: impact of signed versus written questionnaires on the prevalence of psychopathology among deaf adolescents. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40:665–673. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis JM, Elfenbein J, Schum R, Bentler R. Effects of mild and moderate hearing impairments on language, educational and psychosocial behavior of children. J Speech Hear Disord. 1986;51:53–62. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5101.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edwards L, Khan S, Broxholme C, Langdon D. Exploration of the cognitive and behavioural consequences of paediatric cochlear implantation. Cochlear Implants Int. 2006;7:61–76. doi: 10.1179/146701006807508070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fundudis T, Kolvin I, Garside R. Speech retarded and deaf children: their psychological development. London: Academic Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Furstenberg K, Doyal G. The relationship between emotional-behavioral functioning and personal characteristics on performance outcomes of hearing impaired students. Am Ann Deaf. 1994;139:410–414. doi: 10.1353/aad.2012.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kammerer E. Kinderpsychiatrische Aspekte der schweren Hörschädigung [Child psychiatric aspects of severe hearing impairment] Stuttgart: Ferdinand Enke Verlag; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Konuk N, Erdogan A, Atik L, Ugur MB, Simsekyilmaz O. Evaluation of behavioral and emotional problems in deaf children by using the child behavior checklist. Neurol Psychiatry Brain Res. 2006;13:59–64. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kouwenberg M, Rieffe C, Theunissen CPM. Intrapersonal and interpersonal factors related to self reported symptoms of depression in DHH youth. Int J Mental Health Deaf. 2011;1:46–57. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li H, Prevatt F. Deaf and hard of hearing children and adolescents in China: their fears and anxieties. Am Ann Deaf. 2010;155:458–466. doi: 10.1353/aad.2010.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mitchell TV, Quittner AL. Multimethod study of attention and behaviour problems in hearing-impaired children. J Clin Child Psychol. 1996;25:83–96. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prior MR, Glazner J, Sanson A, Debelle G. Research note: temperament and behavioural adjustment in hearing impaired children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1988;29:209–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1988.tb00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quittner AL, Barker DH, Cruz I, Snell C, Grimley ME, Botteri M, The CDaCI Investigative Team Parenting stress among parents of deaf and hearing children: associations with language delays and behavior problems. Parent Sci Pract. 2010;10:136–155. doi: 10.1080/15295190903212851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Remine MD, Brown PM. Comparison of the prevalence of mental health problems in deaf and hearing children and adolescents in Australia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44:351–357. doi: 10.3109/00048670903489866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rutter M, Graham P, Yule W. A neuropsychiatric study in childhood. Clinics in developmental medicine Nos. 35/36. London: Spastics International Medical Publications; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sahli S, Arslan U, Belgin E. Depressive emotioning in adolescents with cochlear implant and normal hearing. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:1774–1779. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sinkkonen J. Hearing impairment, communication and personality development. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Helsinki: University of Helsinki; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tharpe AM, Ashmead DH, Rothpletz AM. Visual attention in children with normal hearing, children with hearing aids, and children with cochlear implants. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2002;45:403–413. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/032). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Theunissen SCPM, Rieffe C, Kouwenberg M, Soede W, Briaire JJ, Frijns JHM. Depression in hearing-impaired children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;75:1313–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Theunissen SCPM, et al. Anxiety in children with hearing aids or cochlear implants compared to normally hearing controls. Laryngoscope. 2012;12:654–659. doi: 10.1002/lary.22502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Theunissen SCPM, et al. Behavioral problems in school-aged hearing-impaired children: the influence of sociodemographic, linguistic, and medical factors. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23:187–196. doi: 10.1007/s00787-013-0444-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Topol D, Girard N, St Pierre L, Tucker R, Vohr B. The effects of maternal stress and child language ability on behavioral outcomes of children with congenital hearing loss at 18–24 months. Early Hum Dev. 2011;87:807–811. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Eldik TT. Behavior problems with deaf Dutch boys. Am Ann Deaf. 1994;139:394–399. doi: 10.1353/aad.2012.0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Eldik TT. Mental health problems of Dutch youth with hearing loss as shown on the Youth Self-Report. Am Ann Deaf. 2005;150:11–16. doi: 10.1353/aad.2005.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wake M, Hughes EK, Poulakis Z, Collins C, Rickards FW. Outcomes of children with mild-profound congenital hearing loss at 7–8 years: a population study. Ear Hear. 2004;25:1–8. doi: 10.1097/01.AUD.0000111262.12219.2F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watt JD, Davis FE. The prevalence of boredom proneness and depression among profoundly deaf residential school adolescents. Am Ann Deaf. 1991;136:409–413. doi: 10.1353/aad.2012.0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stott DH. The social adjustment of children: manual of the Bristol Social Adjustment Guides. 5. London: Hodder and Stoughton; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rutter M. A children’s behaviour questionnaire for completion by teachers: preliminary findings. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1967;8:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1967.tb02175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C. Manual for the teacher’s report form and teacher version of the child behavior profile. Burlington: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rutter M, Tizard J, Whitmore K, editors. Education, health and behaviour. London: Longmans; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goyette CH, Conners CK, Ulrich RF. Normative data on revised Conners parent and teacher rating scales. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1978;6:221–236. doi: 10.1007/BF00919127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Achenbach TM. Manual for the YSR and 1991 profile. Burlington: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Achenbach TM. Child Behavior Checklist 1.5–5. Burlington: ASEBA; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth and Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kovacs M. The Childrens’ Depression Inventory (CDI) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1985;21:995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gadow K, Sprafkin J. Child Symptom Inventories. Checkmate plus. NY: Stony Brook; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BE, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eyberg S, Ross AW. Assessment of child behavior problems: the validation of a new inventory. J Clin Child Psychol. 1978;7:113–116. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Behar L, Stringfield SA. Behaviour rating scale for the preschool child. Dev Psychol. 1974;10:601–610. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sawyer M, Arney F, Baghurst P, et al. The mental health of young people in Australia: key findings from the child and adolescent component of the national survey of mental health and wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35:806–814. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000097. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.van Driel ML, De Sutter A, De Maeseneer J, Christiaens T. Searching for unpublished trials in Cochrane reviews may not be worth the effort. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:838–844. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dammeyer J. Children with Usher syndrome: mental and behavioural disorders. Behav Brain Funct. 2012;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Timmerman A, Meesters C, Anteunis L, Chenault M. Level of psychosocial adaptation in young school children with otitis media. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71:1843–1848. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fellinger J, Holzinger D, Beitel C, Laucht M, Goldberg DP. The impact of language skills on mental health in teenagers with hearing impairments. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;120:153–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fellinger J, Holzinger D, Sattel H, Laucht M, Goldberg D. Correlates of mental health disorders among children with hearing impairments. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009;51:635–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fellinger J, Holzinger D. Enhancing resilience to mental health disorders in deaf school children. In: Zand DH, Pierce KJ, editors. Resilience in deaf children: adaptation through emerging adulthood. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 230–257. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Garg S, et al. Autism and other psychiatric comorbidity in neurofibromatosis type 1: evidence from a population-based study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55:139–145. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gurney JG, Tersak JM, Ness KK, Landier W, Matthay KK, Schmidt ML. Hearing loss, quality of life, and academic problems in long-term neuroblastoma survivors: report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatrics. 2007;120:E1229–E1236. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hintermair M. Socio-emotional problems among hearing-impaired children—initial results of the German version of the Strenghts and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ-D) Z Kinde Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2006;34:49–61. doi: 10.1024/1422-4917.34.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hintermair M. Executive functions and behavioral problems in deaf and hard-of-hearing students at general and special schools. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2013;18:344–359. doi: 10.1093/deafed/ent003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hutchison T, Gordon D. Ascertaining the prevalence of childhood disability. Child Care Health Dev. 2005;31:99–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2005.00462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ketelaar L, Rieffe C, Wiefferink CH, Frijns JHM. Social competence and empathy in young children with cochlear implants and with normal hearing. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:518–523. doi: 10.1002/lary.23544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Marret S, et al. Special outpatient services at 5 and 8 years in very-preterm children in the EPIPAGE study. Arch Pediatr. 2009;16:S17–S27. doi: 10.1016/S0929-693X(09)75297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McCormack J, Harrison LJ, McLeod S, McAllister L. A nationally representative study of the association between communication impairment at 4–5 years and children’s life activities at 7–9 years. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2011;54:1328–1348. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2011/10-0155). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Moller K. Deaf blindness: a challenge for assessment—is the ICF a useful tool? Int J Audiol. 2003;42:S140–S142. doi: 10.3109/14992020309074635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Muigg F, Nekahm-Heis D, Juen F. Hearing impaired children in regular schools—self-concept, integration experience, psycho-social aspects and educational frameworks. Sprache-Stimme-Gehor. 2010;34:237–242. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rieffe C, Ketelaar L, Wiefferink CH. Assessing empathy in young children: construction and validation of an Empathy Questionnaire (EmQue) Pers Individ Diff. 2010;49:362–367. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Saigal S, et al. Comparison of current health, functional limitations, and health care use of young adults who were born with extremely low birth weight and normal birth weight. Pediatrics. 2007;119:E562–E573. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.St Clair MC, Pickles A, Durkin K, Conti-Ramsden G. A longitudinal study of behavioral, emotional and social difficulties in individuals with a history of specific language impairment (SLI) J Commun Disord. 2011;44:186–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sumpter R, Brunklaus A, McWilliam R, Dorris L. Health-related quality-of-life and behavioural outcome in survivors of childhood meningitis. Brain Inj. 2011;25:1288–1295. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2011.613090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Watson L, Brown PM. Editorial. Deaf Educ Int. 2012;14:121. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Anmyr L, Larsson K, Olsson M, Freijd A. Strengths and difficulties in children with cochlear implants—comparing self-reports with reports from parents and teachers. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;76:1107–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Meltzer H, Gatward R, Goodman R, Ford F. Mental health of children and adolescents in Great Britain. London: The Stationery Office; 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cornes AJ, Brown PM. Mental health of Australian deaf adolescents: an investigation using an Auslan version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Deaf Educ Int. 2012;14:161–175. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Goodman R. Psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1337–1345. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dammeyer J. Psychosocial development in a Danish population of children with cochlear implants and deaf and hard-of-hearing children. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2010;15:50–58. doi: 10.1093/deafed/enp024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Smedje H, Broman JE, Hetta J, von Knorring AL. Psychometric properties of a Swedish version of the ‘‘Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaires’’. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;8:63–70. doi: 10.1007/s007870050086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fellinger J, Holzinger D, Sattel H, Laucht M. Mental health and quality of life in deaf pupils. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;17:414–423. doi: 10.1007/s00787-008-0683-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Woerner W, Becker A, Rothenberge A. Normative data and scale properties of the German parent SDQ. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;13 (Suppl 2)(2):3–10. doi: 10.1007/s00787-004-2002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hintermair M. Prevalence of socioemotional problems in deaf and hard of hearing children in Germany. Am Ann Deaf. 2007;152:320–330. doi: 10.1353/aad.2007.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hogan A, Phillips RL, Howard D, Yienprugsawan V. Psychosocial outcomes of children with ear infections and hearing problems: a longitudinal study. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:65–73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Huber M, Kipman U. The mental health of deaf adolescents with cochlear implants compared to their hearing peers. Int J Audiol. 2011;50:146–154. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2010.533704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mejstad L, Heiling K, Svedin CG. Mental health and self-image among deaf and hard of hearing children. Am Ann Deaf. 2009;153:504–515. doi: 10.1353/aad.0.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Van Roy B, Grøholt B, Heyerdahl S, Clench-Aas J. Self-reported strengths and difficulties in a large Norwegian population 10–19 years: age- and gender-specific results of the extended SDQ questionnaire. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15:189–198. doi: 10.1007/s00787-005-0521-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Koskelainen M, Sourander A, Vauras M. Self-reported strengths and difficulties in a community sample of Finnish adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;10:180–185. doi: 10.1007/s007870170024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Stevenson J, et al. The effect of early confirmation of hearing loss on the behaviour in middle childhood of children with bilateral hearing impairment. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53:269–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03839.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]