Abstract

Colorectal carcinoma (CRC) is the third most common cancer in developed countries. A large fraction of cases are linked to chronic intestinal inflammation, with concomitant increased TNF-α release and elevated Snail1/Snail2 levels. These transcription factors in turn suppress vitamin D receptor (VDR) expression, resulting in loss of responsiveness to the protective anti-proliferative and anti-migratory effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25D). Experimental and epidemiologic evidence support the use of natural products to target CRC. Here we show that the flavonolignan silibinin reverses the TNF-α-induced upregulation of Snail1 and Snail2 in the 1,25D-resistant human colon carcinoma cells HT-29. These silibinin effects are accompanied by an increase in VDR levels; Snail1 overexpression reverses these silibinin effects. Silibinin also restores promoter activity from a vitamin D-response element (VDRE) reporter construct. While 1,25D had no significant effect on HT-29 and SW480-R cell proliferation and migration, co-treatment with silibinin restored 1,25D responsiveness. In addition, co-treatment with silibinin plus 1,25D decreased proliferation and migration at doses where silibinin alone had no effect. These findings demonstrate that this combination may present a novel approach to target CRC in conditions of chronic colonic inflammation.

Keywords: Inflammation, Colon cancer, Snail1, Snail2, Vitamin D receptor

Introduction

Colorectal carcinoma (CRC) is the third most common cancer diagnosed in both men and women globally [1]. Only about 20% of CRC cases have a familial basis [2]. The largest fraction of CRC cases has been linked to risk factors including chronic intestinal inflammation, environmental and food-borne mutagens, and specific intestinal commensals and pathogens [3]. The connection between inflammation and CRC is now well-established, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an important risk factor for the development of CRC, as has been reported in patients with chronic ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease [3–5].

An inverse correlation exists between CRC incidence and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25D) levels [6]. 1,25D decreases cell proliferation and induces cell differentiation and apoptosis [7,8]. Vdr−/− mice show hyper-proliferation and increased mitotic activity in the colon [9]. VDR levels are decreased in the inflamed colon and in CRC, and there is an inverse correlation between VDR levels and epithelial/mesenchymal transition [10,11]. VDR expression is a favorable prognostic indicator in CRC [6,12–14]. Expression of the transcription factors Snail1 and Snail2 are increased in both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, as well as with CRC progression [15,16]. Both Snail1 and Snail 2 decrease VDR levels, leading to failure of therapy with 1,25D analogs [11,16]. To signal, VDR must heterodimerize with a member of the retinoid X receptor (RXR) family [17,18]. Downregulation of both the VDR and RXRα is associated with an early increase in Snail1 and Snail2 expression in a murine model of colitis [18]. Maintaining a positive response to 1,25D would be expected to prove beneficial in conditions of chronic inflammation.

Epidemiological studies strongly support evidence that dietary components can exert protective effects [19–21]. Silibinin, a flavonolignan isolated from milk thistle seeds, decreases Snail1 and Snail 2 levels in prostate cancer cells [22–24]. Silibinin also inhibits azoxymethane-induced aberrant crypt foci formation [25] and xenograft growth of the human colon carcinoma cell line HT-29 in nude mice [26]. Using HT-29 cells, here we asked if suppression of Snail1 and Snail2 expression by silibinin restores responsiveness to 1,25D. HT-29 cells have been widely used to model the physiology and immune function of intestinal epithelial cells [27,28]. We also assessed the effects of silibinin in the 1,25D-resistant colon cancer cell line SW480-R [10].

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) was used to upregulate Snail1 and Snail2 expression. This cytokine, which is expressed at elevated levels in most colon cancers, has been associated with cancer promotion [3]. TNF-α is produced during the initial inflammatory response, and initiates multiple downstream events, including release of other cytokines, chemokines, and endothelial adhesion molecules [3]. TNF-α promotes colorectal and colitis-associated tumor development, and its levels are elevated in patients with Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis and other forms of IBD [29–31]. Patients at increased risk of colorectal adenoma have detectable serum TNF-α levels [32]. The secretion pattern of TNF-α from HT-29 cells in response to invasive bacteria is similar to that of freshly isolated intestinal epithelial cells [27,28].

Materials and methods

Materials

1,25D and silibinin were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). 1,25D was dissolved in ethanol at 10−3M, and silibinin was dissolved in DMSO at 100 mM. TNF-α was purchased from R&D Biosystems (Minneapolis, MN) and was dissolved in PBS containing 0.1% BSA at 10 μg/0.5 ml. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and dialyzed FBS were obtained from Atlanta Biologicals (Norcross, GA). Tissue culture supplies were purchased from Mediatech (Manassas, VA). Antibodies for Western blot analysis were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Cell culture and transfection

HT-29 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and were grown at 37 °C in a humidified 95% air/5% CO2 atmosphere in McCoy’s 5A medium supplemented with 10% FBS and L-glutamine. The SW480-R (SW480-rounded) cell line has been developed by Pálmer et al. [10] and was obtained from Dr. X. Cheng (University of Houston). These cells were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS and L-glutamine.

To determine the effect of 1,25D and silibinin on VDRE-mediated promoter activity, cells were plated onto 24-well plates at 1 × 105 cells/well, then transferred to serum-free medium after 24 h. Cells were transfected with a construct containing the VDRE [33] cloned in the firefly luciferase reporter plasmid pGL-3-Promoter vector (Promega, Madison, WI), or with a construct containing a 677 bp region (−618 to + 59) from the human CYP24A1 promoter [34], cloned in the firefly luciferase reporter plasmid pGL-3-Basic (Promega). Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine Plus (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), per the manufacturer’s specifications. The empty vector was used as control. The cells were co-transfected with a Renilla luciferase construct for standardization purposes. After 4 h, the transfection medium was removed and replaced with fresh medium containing 2.5% FBS plus 1,25D (10−7 M), silibinin (50 μM), or 1,25D + silibinin. Ethanol + DMSO were used as the vehicle control (final volume 0.01% v/v). After 24 h, cell lysates were prepared and promoter activity was assayed using the Dual Luciferase assay kit (Promega). Empty vector control values were subtracted from the respective firefly and Renilla luciferase values. The firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity, and the fold differences were plotted as the firefly/ Renilla ratio.

Analysis of Snail1, Snail2, VDR, RXRα, and CYP24A1 mRNA levels

Cells were plated onto 6-well dishes at 1 × 105 cells/well. When they had reached 70–80% confluence (24–48 h), the cells were transferred to serum-free medium. After 16 h, they were treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml), silibinin (60 μM), or TNF-α plus silibinin. The effects of TNF-α and silibinin on RXRα expression were measured both under serum-free conditions and in the presence of 2.5% FBS. In some experiments, cells were transfected with a Snail1 expressing construct [35], and then treated with silibinin (60 μM). Transfections were performed as in section Cell culture and transfection. The cells were harvested after 24 h, and total RNA was extracted using the RNAqueous® isolation kit (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX), per the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentrations were determined by spectrophotometry. RNA (2.0 μg) was then reverse transcribed into cDNA using the Applied Biosystems cDNA synthesis kit. The cDNA was used for real-time PCR, performed using an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System, Sybr green Supermix (Applied Biosystems), and gene-specific forward and reverse primers. The following primers were used: Snail1, forward, TTCTCTAGGCCCTGGCTGC, reverse, TACTTCTTGACATCTGAGTGGGTCTG [36]; Snail2, forward, CTGGGCTGGCCAAACATAAG, reverse, CCTTGTCACAGTATTTACAG CTGAAAG [36]; VDR, forward AGCAGCGCATCATTGCCATA, reverse CAGCATGG AGAGCTGGGACA [37]; RXRα, forward, TTCGCTAAGCTCTTGCTC, reverse, ATAAG GAAGGTGTCAATGGG [38]; CYP24A1, forward, CAAACCGTGGAAGGCTATC, reverse, AGTCTTCCCCTTCCAGGATCA [39], and 18S, forward TCGGAACTGAGGCCATGATT, reverse CCTCCGACTTTCGTTCTTGATT [36]. The threshold cycle (CT) values for each of the target genes were normalized to those of 18S, and the relative expression level for each of these target genes was calculated using the formula: , where ΔCT represents CT (target sample) – CT (control).

Western blot analysis

Cells were grown in 100 mm plates. When they reached 70–80% confluence, the cells were transferred to serum-free medium. After 16 h, they were treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml), silibinin (60 μM), or TNF-α plus silibinin for 24 h. In some experiments, the cells were transfected with a Snail1-expressing construct [35] and then treated with silibinin (60 μM). Cells were washed twice with cold PBS on ice and lysed in RIPA buffer containing a Protease Inhibitor cocktail and Phosphatase Inhibitor cocktails A and B (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Protein concentrations were estimated using the Bio-Rad protein assay. Protein levels were analyzed by Western blot analysis. β-Actin was used as loading control. The signals were detected using the SuperSignal West Pico Substrate kit (Pierce Biotechnology Inc., Rockford, IL). Densitometric analysis was performed using the Alpha Innotech Image Analysis system (Alpha Innotech Corporation, San Leandro, CA).

Cell proliferation

Cells were plated in 96-well dishes (1 × 104 cells/well) in medium containing 10% dialyzed FBS (to reduce 1,25D levels in medium, and thus enhance responsiveness to exogenously-added 1,25D). After 24 h, the cells were treated with 1,25D (10−11–10−7 M), silibinin (1–100 μM) or combinations of the 2 compounds, as indicated. In some experiments, cells were transfected with a Snail1-expressing construct [35] before treating with silibinin. Cell proliferation was measured after 24 h, 48 h, or 72 h using the Quick Cell Proliferation Assay kit (Biovision; Mountain View, CA).

Monolayer scratch assay

Cells were plated in 6-well dishes in medium containing 10% dialyzed FBS. In some experiments, cells were transfected with a Snail1-expressing construct [35] before treating with silibinin. The cell monolayer was wounded as described [40]. Briefly, when the cells had reached confluence, the cell monolayer was scraped with a P200 pipette tip, and then rinsed with PBS to dislodge cellular debris. The cells were then treated with 1,25D, silibinin, or combinations of the 2 compounds. Pictures were taken before wounding, and at 24, 48 and 72 h after wounding. The extent of migration was analyzed using the NIH image software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/Default.html).

Statistics

Numerical data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M). Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey–Kramer multiple comparisons post-test to determine the statistical significance of differences. Statistical analyses were performed using INSTAT Software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

Results

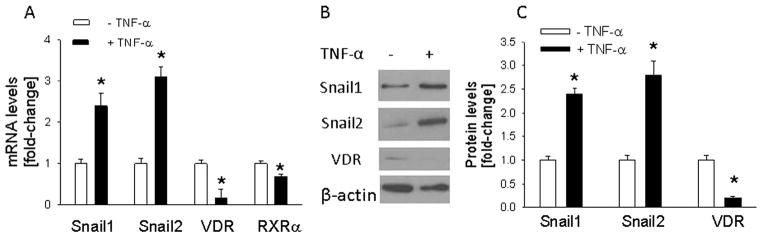

TNF-α regulates Snail1, Snail2, VDR, and RXRα levels in HT-29 cells

Levels of the transcription factors Snail1 and Snail2 are elevated in conditions of chronic inflammation, and are inversely correlated with VDR and RXRα levels [11,16,18]. The pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α is thought to play a role in malignant progression in part through regulation of these pathways [41]. Here we first established an effect of TNF-α on levels of Snail1, Snail2 and the VDR and RXRa in HT-29 cells. Treatment with TNF-α significantly (P < 0.001) increased Snail1 and Snail2 mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 1A–C). Conversely, TNF-α decreased VDR and RXRα mRNA levels (Fig. 1A). The effect on the VDR was more pronounced than that on the RXRα. Thus, when measured in cells cultured in serum-free medium, VDR and RXRα levels after TNF-α treatment were decreased by 85% and 30%, respectively (Fig. 1A). When cells were cultured in 2.5% FBS, TNF-α decreased RXRα mRNA levels by ~50% (data not shown). Western blotting showed low VDR levels which were further decreased by TNF-α (Fig. 1B and C). Since RXRα levels are very low, and the effects of TNF-α on this receptor are modest, protein levels were not measured.

Fig. 1.

Effect of TNF-α on levels of Snail1, Snail2, VDR, and RXRα in HT-29 cells. Cells were stimulated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. (A) mRNA levels were measured by reverse transcription/real-time PCR. (B) Western blot analysis. The figure is representative of data obtained from 3 independent experiments. (C) Densitometric analysis of Western blots. In (A) and (C), values are expressed relative to the –TNF-α control value, set arbitrarily at 1.0. Each bar is the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *Significantly different from the -TNF-α control value (P < 0.001).

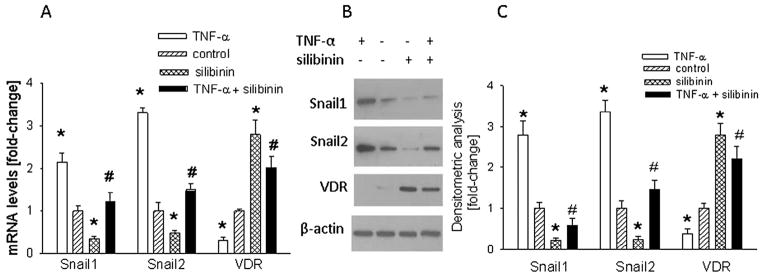

Silibinin attenuates the effects of TNF-α on Snail1, Snail2, and VDR levels

To assess the effects of silibinin on TNF-α-induced regulation of Snail1, Snail2, VDR, and RXRα levels, and hence a potential protective effect of silibinin, HT-29 cells were co-treated with TNF-α + silibinin. Treatment with silibinin alone significantly (P < 0.001) decreased Snail1 and Snail2 mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 2). Silibinin also attenuated the effects of TNF-α on Snail1 and Snail2 levels; there was no significant difference (P > 0.05) in their expression in untreated cells vs. cells co-treated with TNF-α plus silibinin (Fig. 2A and C). Treatment with silibinin significantly (P < 0.001) increased VDR levels and attenuated the TNF-α-induced down-regulation of VDR expression, such that there was no significant difference in VDR levels between TNF-α plus silibinin vs. silibinin alone-treated cells (Fig. 2A and C). Conversely, silibinin had no significant effect (P > 0.05) on RXRα levels (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Effect of silibinin on the TNF-α-mediated regulation of Snail1, Snail2, and VDR levels in HT-29 cells. Cells were co-treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) plus silibinin (60 μM) for 24 h. (A) mRNA levels were measured by reverse transcription/real-time PCR. (B) Western blot analysis. The figure is representative of data obtained from 3 independent experiments. (C) Densitometric analysis of Western blots. In (A) and (C), values are expressed relative to the control value, set arbitrarily at 1.0. Each bar is the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *Significantly different from the control value (P < 0.001); #significantly different from the + TNF-α alone value (P < 0.01).

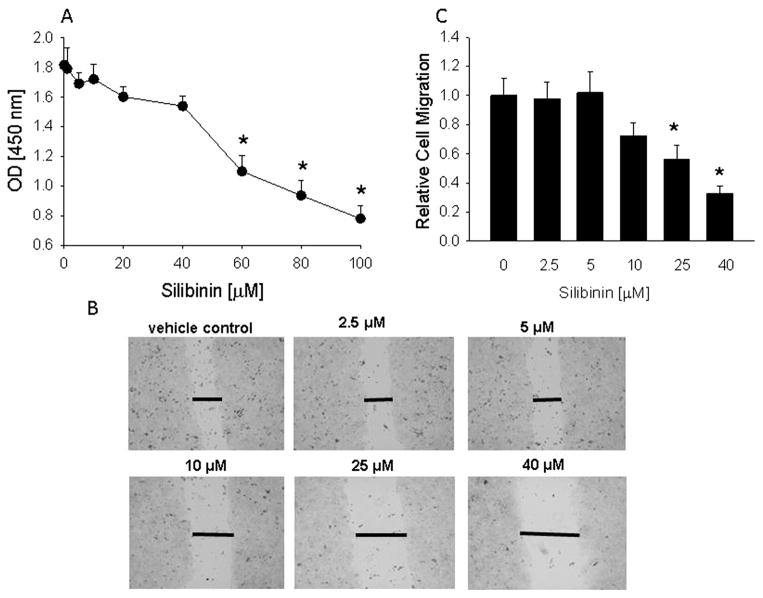

Silibinin, but not 1,25D, decreases HT-29 and SW480-R cell proliferation and migration

Since cancer cells show increased proliferation and migration, here we measured the effect of silibinin on these parameters. Treatment with silibinin for 48 h caused a concentration-dependent decrease in HT-29 cell proliferation. No significant effect (P > 0.05) was observed with concentrations ≤40 μM (Fig. 3A). Similar effects were observed when cells were treated with silibinin for 24 h or 72 h (data not shown). Silibinin also decreased SW480-R cell proliferation. As in HT-29 cells, no significant effect (P > 0.05) was observed with concentrations ≤40 μM, and a concentration of 60 μM decreased SW480-R cell proliferation by ~30% after 48 h treatment (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Effect of silibinin on HT-29 cell proliferation and migration. (A) Cells were treated with the indicated concentration of silibinin for 48 h. Cell proliferation was measured using the Quick Cell Proliferation Assay kit, where optical density (OD) at 450 nm is directly proportional to cell number. (B) Monolayer scratch assay. Images at 48 h after wounding are shown for cells treated with vehicle (control) or the indicated concentrations of silibinin. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. The horizontal lines mark the edges of the monolayer. Magnification, ×10. (C) Quantitation of cell migration. Each bar is the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *Significantly different from (A), 0 time-point and (C), the vehicle control (P < 0.001).

HT-29 cell migration was attenuated by silibinin, as measured using the scratch assay. No significant effect was observed at concentrations ≤5 μM (Fig. 3B and C). An effect was observed at concentrations ≥10 μM (Fig. 3B and C). The maximal effects of silibinin were observed after 48 h of treatment. After 72 h, the vehicle-treated cells had migrated to completely bridge the gap induced by wounding the monolayer. In silibinin-treated cells, the gap was still present after 72 h in cells treated with concentrations of silibinin ≥25 μM (data not shown). Silibinin also decreased SW480-R cell migration. No effect was evident at concentrations ≤20 μM, and 40 μM silibinin decreased migration by ~25% after 24 h (data not shown).

1,25D signaling is associated with decreased proliferation and migration. Treatment with 10−7 M 1,25D for 24–96 h produced an ~20% decrease in HT-29 cell proliferation (P > 0.05) (data not shown). Lower concentrations of 1,25D (10−11–10−8M) produced even smaller effects (data not shown). Similarly, treatment with 1,25D (10−11–10−7M) for 24–96 h had no significant effect on HT-29 cell migration, as measured by the scratch assay (data not shown). These data imply negligible VDR signaling in these cells. As previously reported [10], 1,25D (10−9–10−7 M) for 24–72 h had no significant effect (P > 0.05) on SW480-R cell proliferation (data not shown). The same concentrations of 1,25D also had no effect on SW480-R cell migration (data not shown).

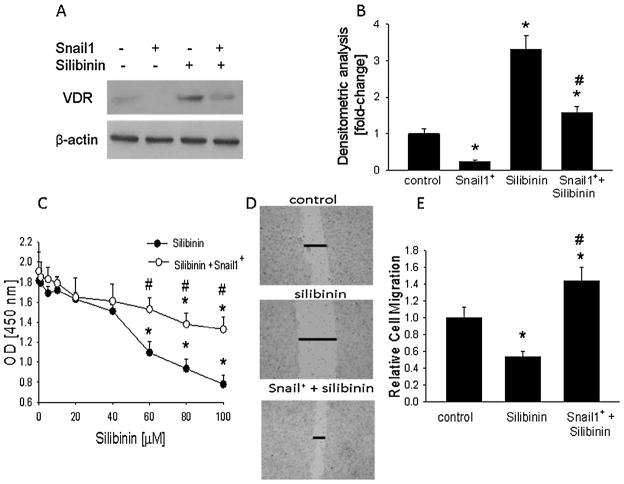

Snail1 overexpression attenuates the effects of silibinin

Treatment with silibinin decreased Snail levels and increased VDR levels (Fig. 2). To assess the role of Snail1 in the silibinin effects on the VDR, levels of the receptor were measured in cells transfected with a Snail1-expressing construct, and then treated with silibinin. Snail1 overexpression was confirmed by Western blotting (data not shown). Overexpressing Snail1 attenuated the upregulatory effects of silibinin on VDR levels, such that VDR levels were significantly lower (P < 0.01) in Snail1-overexpressing cells treated with silibinin vs. control (untransfected) cells treated with silibinin (Fig. 4A and B). Transfection with empty vector had no effect on VDR levels (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Effect of Snail1 overexpression on the silibinin-mediated regulation of VDR expression, and cell proliferation and migration in HT-29 cells. Cells were transfected with a Snail1-expressing construct (Snail+). (A,B) Cells were then treated with silibinin (60 μM) for 24 h. (A) Western blot analysis. The figure is representative of data obtained from 3 independent experiments. (B) Densitometric analysis of Western blots. (C) Cell proliferation. Cells were treated with the indicated concentration of silibinin for 48 h. Proliferation was measured using the Quick Cell Proliferation Assay kit, where optical density (OD) at 450 nm is directly proportional to cell number. (D) Monolayer scratch assay. Images at 48 h after wounding are shown for control cells and cells treated with silibinin (60 μM). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. The horizontal lines mark the edges of the monolayer. Magnification, ×10. (E) Quantitation of cell migration. In (B,C,E), each bar or point is the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *Significantly different from: (B,E) the vehicle control (P < 0.001); (C) the 0 time-point. (B,C,E) #Significantly different from silibinin alone (P < 0.01).

Overexpressing Snail1 attenuated the anti-proliferative effects of silibinin, such that proliferation of silibinin-treated Snail1-overexpressing cells was significantly higher (P < 0.01) than that of untransfected cells treated with silibinin (Fig. 4C). Overexpressing Snail1 also attenuated the anti-migratory effects of silibinin, such that migration of silibinin-treated Snail1-overexpressing cells was significantly higher (P < 0.01) than that of silibinin-treated untransfected cells (Fig. 4D and E). Empty vector alone had no effect on proliferation or migration (data not shown). Any effect of silibinin in Snail1-overexpressing cells may be attributed to Snail1-independent pathways, including those mediated by Snail2.

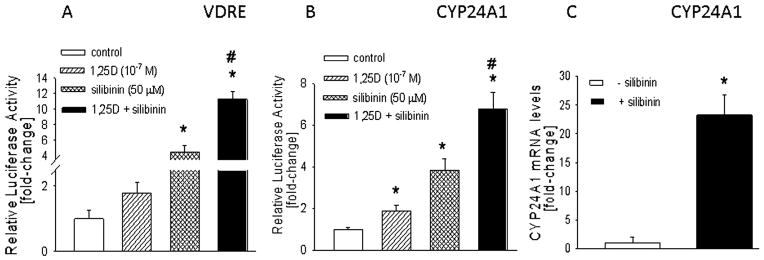

Silibinin restores VDRE-mediated promoter activity

Since 1,25D did not alter HT-29 cell proliferation and migration, we measured promoter activity of a luciferase-VDRE construct in HT-29 cells. As shown in Fig. 5A, VDRE-driven luciferase activity was negligible in control cells (treated with ethanol plus DMSO as vehicle controls). Treatment with 1,25D produced an ~1.5-fold increase (P > 0.05) in luciferase activity, consistent with the presence of low VDR levels in these cells (Fig. 5A). Treatment with vehicle had no effect on promoter activity (data not shown). Silibinin treatment increased VDRE-mediated promoter activity even in the absence of exogenous 1,25D addition (Fig. 5A). We postulate that this response occurs as a result of the silibinin-mediated increase in VDR levels, with the cells responding to the 1,25D contained in FBS present in culture medium. Co-treatment with 1,25D plus silibinin further increased VDRE-driven promoter activity, such that activity was significantly higher (P < 0.001) than that in cells treated with silibinin alone.

Fig. 5.

(A,B) Effect of silibinin on VDRE-mediated promoter activity in HT-29 cells. Cells were co-transfected with a firefly luciferase reporter construct driven by a canonical VDRE (A) or a CYP24A1 promoter region (B), plus a Renilla luciferase construct. After 4 h, cells were treated with 1,25D (10−7M), silibinin (50 μM), or 1,25D + silibinin for 24 h. Control cells were treated with ethanol + DMSO (vehicle controls). Luciferase activity was measured after 24 h. Empty vector control values were subtracted from the respective firefly and Renilla luciferase values. Values were then normalized to Renilla luciferase activity, and are expressed as the firefly/Renilla ratio. The vehicle control value is set arbitrarily at 1.0. (C) Effect of silibinin on CYP24A1 mRNA levels. Cells were treated with silibinin (60 μM) for 24 h. mRNA levels were measured by reverse transcription/real-time PCR. Each bar is the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. In (A–C), *significantly different from the control value (P < 0.001); #significantly different from silibinin or 1,25D alone value (P < 0.01).

1,25D increased luciferase activity driven by a CYP24A1 promoter construct by ~2-fold (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5B). Silibinin alone produced an ~4-fold increase (P < 0.01) in promoter activity (Fig. 5B). When cells were co-treated with 1,25D plus silibinin, promoter activity increased by ~7-fold (P < 0.01); the effect with the combination treatment was significantly higher (P < 0.01) than that with either treatment alone (Fig. 5B). This effect of silibinin on CYP24A1 promoter activity was accompanied by an ~20-fold increase in CYP24A1 mRNA levels (Fig. 5C).

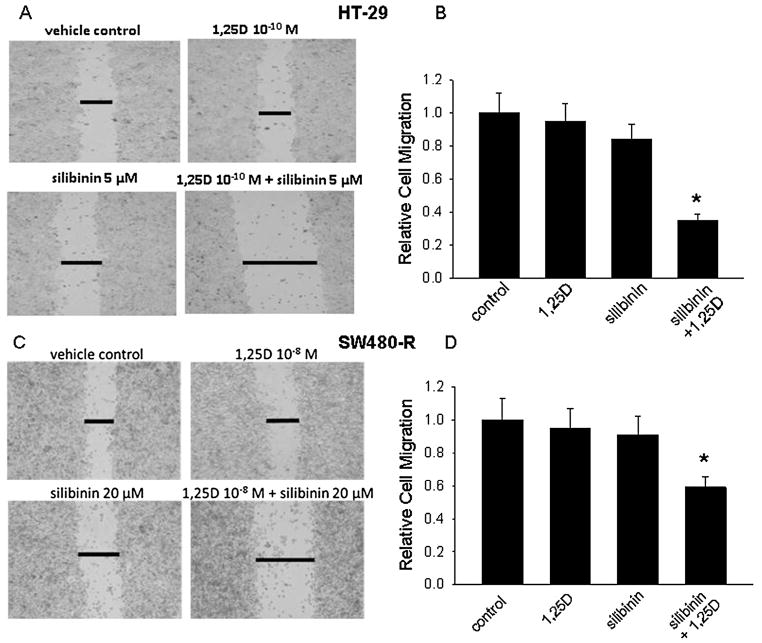

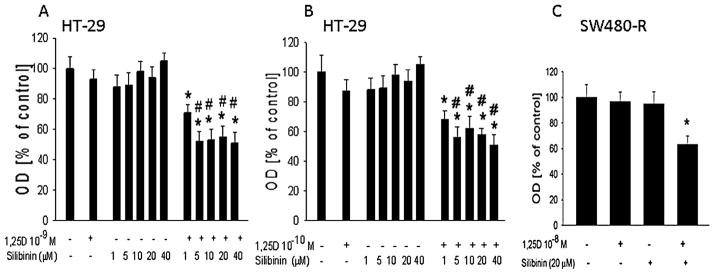

Synergistic effects of silibinin and 1,25D on cell proliferation and migration

Since silibinin restored VDR-mediated promoter activity and increased VDR levels, we asked if it also rendered cells responsive to the anti-proliferative effects of 1,25D. In HT-29 cells, low concentrations of silibinin (1–40 μM) or 1,25D (10−10 M and 10−9 M) alone had no significant effect (P > 0.05) on cell proliferation (Fig. 6A and B). However, co-treatment with silibinin plus 1,25D caused a significant decrease (P < 0.01) in proliferation (Fig. 6A and B). Silibinin also rendered SW480-R cells responsive to the anti-proliferative effects of 1,25D, though these effects were less pronounced than those on HT-29 cells. Thus, treatment with 20 μM silibinin or 10−8 M 1,25D for 48 h had no significant effect on SW480-R cell proliferation, while a combination of silibinin and 1,25D decreased SW480-R cell proliferation by ~35% (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Effect of combination 1,25D plus silibinin on cell proliferation. Cells were treated with the indicated concentration of 1,25D and/or silibinin for 48 h. Cell proliferation was measured using the Quick Cell Proliferation Assay kit, where optical density (OD) at 450 nm is directly proportional to cell number. (A,B) HT-29 cells. (C) SW480-R cells. Each bar is the mean±SEM of three independent experiments. *Significantly different from the vehicle control (P< 0.001); #significantly different from the 1,25D and silibinin alone value (P<0.01).

Similar effects were observed on cell migration. In HT-29 cells, silibinin (5 μM) and 1,25D (10−10M) alone had no significant effect (P > 0.05) on cell migration when compared to vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 7A and B). However, at the same concentrations, the combination silibinin + 1,25D significantly (P< 0.001) decreased cell migration (Fig. 7A and B). The combination treatment also decreased SW480-R cell migration, though again these cells were less responsive than HT-29 cells and higher concentrations of the individual compounds were needed to produce an effect. Thus, while 20 μM silibinin and 10−8M 1,25D alone had no significant effect (P > 0.05), the combination treatment decreased cell migration by ~45% (Fig. 7C and D).

Fig. 7.

Effect of combination 1,25D plus silibinin on cell migration, measured using the monolayer scratch assay. Images at 48 h (HT-29 cells) and 24 h (SW480-R cells) after wounding are shown for cells treated with vehicle (control) or the indicated concentrations of 1,25D and/or silibinin. (A,C)The horizontal lines mark the edges of the monolayer. Magnification, ×10. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B,D) Quantitation of cell migration. Each bar is the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *Significantly different from the vehicle control (P < 0.01).

Discussion

Long-term inflammation of the colon is associated with an increased risk of CRC [3–5]. Multiple observational studies have established that vitamin D exerts a protective effect in the colon through its active metabolite 1,25D [42–45]. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with increased hospitalization and surgery in IBD patients [46]. Vitamin D supplementation prevents relapse via an effect on intestinal permeability and improves muscle strength, fatigue, and quality of life in patients with Crohn’s disease [46]. A correlation exists between serum levels of 25D as a result of nutritional intake and/or exposure to sunlight and incidence of CRC, and higher plasma vitamin D levels are correlated with a reduced risk of CRC [47,48]. However, mixed results have been obtained in several clinical trials addressing the chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic activity of 1,25D analogs [16,47]. Failure of therapy with these 1,25D analogs may be due to loss of VDR expression. In a retrospective study of ulcerative colitis patients, VDR levels were lower in inflamed colonic mucosa vs. normal colon [16]. Additionally, long-term ulcerative colitis patients (≥10 years), who are at a higher risk of developing CRC, have significantly lower VDR levels than short-term patients [48,49]. VDR levels are decreased in low and intermediate grade CRC, compared to normal colon [11]. High grade CRC expresses even lower VDR levels, and there is a reciprocal relationship between VDR levels and epithelial–mesenchymal/transition [10,11]. Here we show that VDR levels are very low in HT-29 cells, and that treatment with TNF-α, a pro-inflammatory mediator that is expressed at elevated levels in most colon cancers and has been associated with cancer promotion [3], further suppresses VDR expression. Low levels of VDR may account for the poor responsiveness of HT-29 cells to the anti-proliferative and anti-migratory effects of 1,25D, as shown in this study.

Levels of Snail1 and Snail2 are elevated in conditions of long-term chronic inflammation and in cancer in response to pro-inflammatory cytokine release [3]. Here we show that TNF-α increases Snail 1 and Snail2 levels in HT-29 cells. Snail1 and Snail2 suppress VDR expression via a transcriptional pathway, causing loss of responsiveness to 1,25D [11,50]. Thus, since the TNF-α-mediated decrease in VDR expression may be secondary to induction of Snail1 and Snail2, suppressing expression/activity of these transcription factors could re-establish VDR expression and responsiveness to 1,25D analogs. VDR heterodimerizes with RXR, and RXRα levels are also downregulated in human CRC [51]. We show that TNF-α suppresses RXRα expression in HT-29 cells. Using the azoxymethane/dextran sodium sulfate mouse model of colitis, Knackstedt et al. [18] showed that VDR was downregulated early in the onset of colitis, while RXRα was downregulated only when colitis became chronic and developed into colitis-associated cancer. These studies underscore the importance of VDR/RXRα signaling in chronic inflammation and CRC.

The flavonolignan silibinin inhibits Snail1 and Snail2 expression in prostate cancer cells [22], and downregulates a number of mitogenic and cell survival signaling pathways in prostate, breast and skin cancer cells, among others [52–54]. Silibinin regulates gene expression and translation initiation of target genes [55–57], and regulates epigenetic pathways through histone deacetylase (HDAC) and DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) [58–60]. Silibinin signals via multiple cell signaling pathways, including ERK1/2, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), NF-κB, and multiple cyclins [52,61–64]. Moreover, silibinin renders human prostate cancer cells sensitive to TNF-α-induced apoptosis [52]. The effects of silibinin on cell proliferation and VDRE transactivation appear to be cell type-specific, and may involve regulation of RXRα [65]. In this study, we show down-regulation of Snail1 and Snail2 levels by silibinin in colon cancer cells. This effect is accompanied by an increase in VDR levels and restoration of VDRE-mediated promoter activity. However, silibinin had no effect on RXRα levels in our system, indicating that the decrease in VDRE-mediated promoter activity by silibinin may predominantly occur via an effect on the VDR. Future studies will address the pathways via which silibinin regulates levels of these and other target genes. Notably, co-treatment with silibinin significantly increased the anti-proliferative and anti-migratory effects of 1,25D. Based on these data, we postulate that re-establishment of VDR expression by silibinin plays a major role in the beneficial anti-proliferative and anti-migratory effects of silibinin. Silibinin exhibits little or no systemic toxicity after acute and chronic administration in animals and humans [66]. However, one of its drawbacks is achieving high enough concentrations to elicit a pharmacological response due to poor bioavailability [67]. In a pilot study, Hoh et al. [68] showed that administration of 360–1440 mg silibinin daily for 7 days to colorectal adenocarcinoma patients achieved plasma silibinin levels in the 0.3–4 μM range and colorectal tissue concentrations in the 20–141 nmol/g range. While silibinin failed to regulate the IGF-I/IGFBP-3 axis in this human study, possibly because it was only administered for 7 days, the doses administered are in the range of those used in our study (≤5 μM) in combination with 1,25D analogs that elicited a biological effect in HT-29 cells (decreased cell proliferation and migration). Future studies will assess the effect of this combination in a murine model of colitis. Further studies will also ask whether this regimen can be utilized for chemopreventive purposes in normal inflamed tissue or cancers that have not undergone EMT. Several non-hypercalcemic analogs have been developed that exert beneficial effects comparable to 1,25D [69–71]. Combination of 1,25D analogs with silibinin would be expected to increase the likelihood of achieving such a favorable response at lower concentrations of either compound alone.

In conclusion, these studies link silibinin, a dietary component, with restoration of 1,25D signaling in colon cancer cells, resulting in restoration of the anti-proliferative and anti-migratory effects of 1,25D. These effects of silibinin are accompanied by a decrease in Snail1 and Snail2 levels, and a concomitant increase in VDR levels. These results demonstrate that this combination may present a new approach for chemotherapeutic intervention targeting CRC.

Highlights.

HT-29 cells were used as a model system for the intestinal epithelial.

TNF-α increased Snail1 and Slug levels, and decreased vitamin D receptor levels.

The TNF-α effects were reversed by the flavonolignan silibinin.

HT-29 cells are resistant to 1,25D’s anti-proliferative and anti-migratory effects.

Co-treatment with silibinin rendered HT-29 cells responsive to 1,25D.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant CA176738. We thank Dr. Xiaodong Cheng (University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston) for the SW480-R cells and Dr. Binhua P. Zhou (University of Kentucky Lexington) for the Snail1-expressing construct.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

None.

References

- 1.http://www.wcrf.org/int/cancer-facts-figures/worldwide-data.

- 2.http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/genetics/colorectal/HealthProfessional/page1.

- 3.Terzic J, Grivennikov S, Karin E, Karin M. Inflammation and colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2101–2114. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson L, Evers BM. Chronic inflammation and pathogenesis of GI and pancreatic cancers. Cancer Treat Res. 2006;130:39–65. doi: 10.1007/0-387-26283-0_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng K, Wolpin BM, Meyerhardt JA, Wu K, Chan AT, Hollis BW, et al. Prospective study of predictors of vitamin D status and survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:916–923. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pereira F, Larriba MJ, Muñoz A. Vitamin D and colon cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2012;19:R51–R71. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verlinden L, Verstuyf A, Convents R, Marcelis S, VanCamp M, Bouillon R. Action of 1,25(OH)2D3 on the cell cycle genes, cyclin D1, p21 and p27 in MCF-7 cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1998;142:57–65. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kallay E, Pietschmann P, Toyokuni S, Bajna E, Hahn P, Mazzucco K, et al. Characterization of a vitamin D receptor knockout mouse as a model of colorectal hyperproliferation and DNA damage. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1429–1435. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.9.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pálmer HG, González-Sancho J, Espada J, Berciano MT, Puig I, Baulida J, et al. Vitamin D3 promotes the differentiation of colon carcinoma cells by the induction of E-cadherin and the inhibition of β-catenin signaling. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:369–387. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200102028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pálmer HG, Larriba MJ, García JM, Ordóñez-Morán P, Peña C, Peiró S, et al. The transcription factor SNAIL represses vitamin D receptor expression and responsiveness in human colon cancer. Nat Med. 2004;10:917–919. doi: 10.1038/nm1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cross HS, Bajna E, Bises G, Genser D, Kallay E, Pötzi R, et al. Vitamin D receptor and cytokeratin expression may be progression indicators in human colon cancer. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:2333–2337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans SRT, Noll J, Hanfelt J, Shabahang M, Nauta RJ, Shchepotin IB. Vitamin D receptor expression as a predictive marker of biological behaviour in human colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:1591–1595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cross HS, Bareis P, Hofer H, Bischof MG, Bajna E, Kriwanek S, et al. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3-1α-hydroxylase and vitamin D receptor gene expression in human colonic mucosa is elevated during early carcinogenesis. Steroids. 2001;66:287–292. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(00)00153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bezdekova M, Brychtova S, Sedlakova E, Langova K, Brychta T, Belej K. Analysis of Snail-1, E-Cadherin and Claudin-1 expression in colorectal adenomas and carcinomas. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:1632–1643. doi: 10.3390/ijms13021632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larriba MJ, Muñoz A. SNAIL vs vitamin D receptor expression in colon cancer: therapeutics implications. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:985–989. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mangelsdorf DJ, Evans RM. The RXR heterodimers and orphan receptors. Cell. 1995;83:841–850. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knackstedt RW, Moseley VR, Sun S, Wargovich MJ. Vitamin D receptor and retinoid X receptor α status and vitamin D insufficiency in models of murine colitis. Cancer Prev Res. 2013;6:585–593. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrari P, Day NE, Boshuizen HC, Roddam A, Hoffmann K, Thiébaut A, et al. The evaluation of the diet/disease relation in the EPIC study: considerations for the calibration and the disease models. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:368–378. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehta RG, Murillo G, Naithani R, Peng X. Cancer chemoprevention by natural products: how far have we come? Pharm Res. 2010;27:950–961. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0085-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brenner DE. Multiagent chemopreventive agent combinations. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 2000;34:121–124. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(2000)77:34+<121::aid-jcb19>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raina K, Rajamanickam S, Singh RP, Deep G, Chittezhath M, Agarwal R. Stage-specific inhibitory effects and associated mechanisms of silibinin on tumor progression and metastasis in transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate model. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6822–6830. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh RP, Raina K, Sharma G, Agarwal R. Silibinin inhibits established prostate tumor growth, progression, invasion, and metastasis and suppresses tumor angiogenesis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate model mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7773–7780. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deep G, Gangar SC, Agarwal C, Agarwal R. Role of E-cadherin in anti-migratory and anti-invasive efficacy of silibinin in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Prev Res. 2011;4:1222–1232. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Velmurugan B, Singh RP, Tyagi A, Agarwal R. Inhibition of azoxymethane-induced colonic aberrant crypt foci formation by silibinin in male Fisher 344 rats. Cancer Prev Res. 2008;5:376–384. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh RP, Gu M, Agarwal R. Silibinin inhibits colorectal cancer growth by inhibiting tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2008a;68:2043–2050. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jung HC, Eckmann L, Yang SK, Panja A, Fierer J, Morzycka-Wroblewska E, et al. A distinct array of proinflammatory cytokines is expressed in human colon epithelial cells in response to bacterial invasion. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:55–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI117676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruno MEC, Kaetzel CS. Long-term exposure of the HT-29 human intestinal epithelial cell line to TNF causes sustained up-regulation of the polymeric Ig receptor and proinflammatory genes through transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms. J Immunol. 2005;174:7278–7284. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang S, Liu Z, Wang L, Zhang X. NF-kappaB signaling pathway, inflammation and colorectal cancer. Cell Mol Immunol. 2009;6:327–334. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2009.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Popivanova BK, Kitamura K, Wu Y, Kondo T, Kagaya T, Kaneko S, et al. Blocking TNF-alpha in mice reduces colorectal carcinogenesis associated with chronic colitis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:560–570. doi: 10.1172/JCI32453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kollias G. Modeling the function of tumor necrosis factor in immune pathophysiology. Autoimmun Rev. 2004;3(Suppl 1):S24–S25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim S, Keku TO, Martin C, Galanko J, Woosley JT, Schroeder JC, et al. Circulating levels of inflammatory cytokines and risk of colorectal adenomas. Cancer Res. 2008;68:323–328. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maestro B, Dávila N, Carranza MC, Calle C. Identification of a vitamin D response element in the human insulin receptor gene promoter. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;84:223–230. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roff A, Wilson RT. A novel SNP in a vitamin D response element of the CYP24A1 promoter reduces protein binding, transactivation, and gene expression. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;112:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou BP, Deng J, Xia W, Xu J, Li YM, Gunduz M, et al. Dual regulation of Snail by GSK-3β-mediated phosphorylation in control of epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:931–940. doi: 10.1038/ncb1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fenouille N, Tichet M, Dufies M, Pottier A, Mogha A, Soo JK, et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) regulatory factor SLUG (SNAI2) is a downstream target of SPARC and AKT in promoting melanoma cell invasion. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e40378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pascussi JM, Robert A, Nguyen M, Walrant-Debray O, Garabedian M, Martin P, et al. Possible involvement of pregnane X receptor-enhanced CYP24 expression in drug-induced osteomalacia. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:177–186. doi: 10.1172/JCI21867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kimura Y, Suzuki T, Kaneko C, Darnel AD, Moriya T, Suzuki S, et al. Retinoid receptors in the developing human lung. Clin Sci. 2002;103:613–621. doi: 10.1042/cs1030613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Horváth HC, Lakatos P, Kósa JP, Bácsi K, Borka K, Bises G, et al. The candidate oncogene CYP24A1: a potential biomarker for colorectal tumorigenesis. J Histochem Cytochem. 2010;58:277–285. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2009.954339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhatia V, Saini MK, Shen X, Bi LX, Qiu S, Weigel NL, et al. EB1089 inhibits the PTHrP-enhanced bone metastasis and xenograft growth of human prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:1787–1798. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klampfer L. Cytokines, inflammation and colon cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2011;11:451–464. doi: 10.2174/156800911795538066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fleet JC, DeSmet M, Johnson R, Li Y. Vitamin D and cancer: a review of molecular mechanisms. Biochem J. 2012;441:61–76. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giardina C, Madigan JP, Godman Tierney CA, Brenner BM, Rosenberg DW. Vitamin D resistance and colon cancer prevention. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:475–482. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Byers SW, Rowlands T, Beildeck M, Bong YS. Mechanism of action of vitamin D and the vitamin D receptor in colorectal cancer prevention and treatment. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2012;13:31–38. doi: 10.1007/s11154-011-9196-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yee YK, Chintalacharuvu SR, Lu J, Nagpal S. Vitamin D receptor modulators for inflammation and cancer. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2005;5:761–778. doi: 10.2174/1389557054553785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raftery T, O’Sullivan M. Optimal vitamin D levels in Crohn’s disease: a review. Proc Nutr Soc. 2014;11:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0029665114001591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Welsh J. Cellular and molecular effects of vitamin D on carcinogenesis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;523:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cross HS, Nittke T, Kallay E. Colonic vitamin D metabolism: implications for the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;347:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kong J, Zhang Z, Musch MW, Ning G, Sun J, Hart J, et al. Novel role of the vitamin D receptor in maintaining the integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G208–G216. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00398.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Larriba MJ, Martín-Villar E, García JM, Pereira F, Peña C, García de Herreros A, et al. Snail2 cooperates with Snail1 in the repression of vitamin D receptor in colon cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1459–1468. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang F, Meng F, Li H, Dong Y, Yang W, Han A. Suppression of retinoid X receptor alpha and aberrant β-catenin expression significantly associates with progression of colorectal carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2060–2067. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dhanalakshmi S, Singh RP, Agarwal C, Agarwal R. Silibinin inhibits constitutive and TNFα-induced activation of NF-kB and sensitizes human prostate carcinoma DU145 cells to TNFα-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 2002;21:1759–1767. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deep G, Agarwal R. Antimetastatic efficacy of silibinin: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential against cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:447–463. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9237-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ahmad N, Gali H, Javed S, Agarwal R. Skin cancer chemopreventive effects of a flavonoid antioxidant silymarin are mediated via impairment of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and perturbation in cell cycle progression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;247:294–301. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bobilev I, Novik V, Levi I, Shpilberg O, Levy J, Sharoni Y, et al. The Nrf2 transcription factor is a positive regulator of myeloid differentiation of acute myeloid leukemia cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;11:317–329. doi: 10.4161/cbt.11.3.14098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim KD, Lee HJ, Lim SP, Sikder MA, Lee SY, Lee CJ. Silibinin regulates gene expression, production and secretion of mucin from cultured airway epithelial cells. Phytother Res. 2012;26:1301–1307. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lin CJ, Sukarieh R, Pelletier J. Silibinin inhibits translation initiation: implications for anticancer therapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:1606–1612. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kauntz H, Bousserouel S, Gossé F, Raul F. Epigenetic effects of the natural flavonolignan silibinin on colon adenocarcinoma cells and their derived metastatic cells. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:1273–1277. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mateen S, Raina K, Jain AK, Agarwal C, Chan D, Agarwal R. Epigenetic modifications and p21-cyclin B1 nexus in anticancer effect of histone deacetylase inhibitors in combination with silibinin on non-small cell lung cancer cells. Epigenetics. 2012;7:1161–1172. doi: 10.4161/epi.22070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mateen S, Raina K, Agarwal C, Chan D, Agarwal R. Silibinin synergizes with histone deacetylase and DNA methyltransferase inhibitors in upregulating E-cadherin expression together with inhibition of migration and invasion of human non-small cell lung cancer cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;345:206–214. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.203471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sharma Y, Agarwal C, Singh AK, Agarwal R. Inhibitory effect of silibinin on ligand binding to erbB1 and associated mitogenic signaling, growth, and DNA synthesis in advanced human prostate carcinoma cells. Mol Carcinog. 2001;30:224–236. doi: 10.1002/mc.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zi X, Zhang J, Agarwal R, Pollak M. Silibinin upregulates insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 expression and inhibits proliferation of androgen independent prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5617–5620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tyagi A, Agarwal C, Agarwal R. The cancer preventive flavonoid silibinin causes hypophosphorylation of Rb/p107 and Rb2/p130 via modulation of cell cycle regulators in human prostate carcinoma DU145 cells. Cell Cycle. 2002;1:137–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tyagi A, Agarwal C, Agarwal R. Inhibition of retinoblastoma protein (Rb) phosphorylation at serine sites and an increase in Rb-E2F complex formation by silibinin in androgen-dependent human prostate carcinoma LNCaP cells: role in prostate cancer prevention. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:525–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wasserman R, Novik V, Danilenko M. Cell-type-specific effects of silibinin on vitamin D-induced differentiation of acute myeloid leukemia cells are associated with differential modulation of RXRα levels. Leuk Res Treat. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/401784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hahn G, Lehmann HD, Kürten M, Uebel H, Vogel G. Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn. Arzneimittelforschung. 1968;18:698–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Klempner SL, Bubley G. Complementary and alternative medicines in prostate cancer: from bench to bedside? Oncologist. 2012;17:830–837. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hoh C, Boocock D, Marczylo T, Singh R, Berry DP, Dennison AR, et al. Pilot study of oral silibinin, a putative chemopreventive agent, in colorectal cancer patients: silibinin levels in plasma, colorectum, and liver and their pharmacodynamic consequences. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2944–2950. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hansen CM, Hamberg KJ, Binderup E, Binderup L. Seocalcitol (EB 1089): a vitamin D analogue of anti-cancer potential. Background, design, synthesis, preclinical and clinical evaluation. Curr Pharm Des. 2000;6:803–828. doi: 10.2174/1381612003400371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bischof MG, Redlich K, Schiller C, Chirayath MV, Uskokovic M, Peterlik M, et al. Growth inhibitory effects on human colon adenocarcinoma-derived Caco-2 cells and calcemic potential of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 analogs: structure-function relationships. J Pharm Exp Ther. 1995;275:1254–1260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Harris DM, Go VLW. Vitamin D and colon carcinogenesis. International Research Conference on Food, Nutrition and Cancer. J Nutr. 2004;134:3463S–3471S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.12.3463S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]