Abstract

Introduction

The interpretation of equivocal Papanicolaou (Pap) smear results remains challenging, even with the addition of the high-risk human papillomavirus test (HPV-HR). Recently, methylated zinc finger protein 582 (ZNF582) (ZNF582m) was reported to be highly associated with cervical cancer. In this study, we compared the performance of ZNF582m detection and HPV-HR genotyping in the triage of cervical atypical squamous cell of undetermined significance (ASC-US) and atypical squamous cell - cannot exclude a high-grade lesion (ASC-H).

Case description

Two hundred and forty-two subjects with equivocal papanicolaou smear (Pap smear) results were recruited in this hospital-based and case-controlled study. The residual cervical cells in liquid-based cytological test (LBC) containers were used for genomic DNA extraction and then for ZNF582m and HPV-HR detection. The level of ZNF582m was quantified by real-time methylation-specific PCR after bisulfite conversion. The HPV-HR test was performed by using a nested multiplex PCR (NMPCR) assay that combines degenerate E6/E7 consensus primers and HPV type-specific primers.

Discussion and evaluation

Significant associations were observed between ZNF582m and the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or higher (CIN3+; odds ratio = 15.52, 95% confidence interval (CI): 7.73 to 31.18). The sensitivity and specificity of ZNF582m for women with CIN3+ were 82.43% and 76.79%, respectively. High sensitivity (99.33%) but low specificity (38.76%) was observed for HPV-HR. When combining both positive results of ZNF582m and HPV-HR, the sensitivity and specificity were 82.43% and 81.55%, respectively. The sensitivity and specificity of ZNF582m or HPV-16/18 were 89.19% and 70.24%, respectively. However, the sensitivity and specificity of ZNF582m combined with HPV-16/18 (both ZNF582m and HPV-16/18 positive results) were 59.46% and 94.64%, respectively.

Conclusions

ZNF582m provides a promising triage tool for women with ASC.

To effectively manage ASC patients, a new strategy co-testing for ZNF582m and HPV-16/18 genotyping was proposed. This strategy could reduce the number of patients referred for colposcopic examination and thus provide a feasible follow-up solution in the regions where colposcopy is not readily available. This strategy could also prevent women from experiencing unnecessary anxiety caused by HPV-HR.

Keywords: Biomarker, DNA methylation, HPV-HR, HPV-16/18, Cervical cancer, ZNF582

Background

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer that affects women worldwide. In China, approximately 58,000 new cases and 20,000 deaths were documented in 2005 [1-5]. Screening with the cytological test developed by George Papnicolaou (the Pap test) has led to a significant reduction in the incidence of cervical cancer over the past few decades. However, the optimal treatment regimen for women with atypical squamous cell (ASC) is not well established. In the case of an ASC smear result, a pathologist has to specify the type as either atypical squamous cell of undetermined significance (ASC-US) or cannot exclude a high-grade lesion (ASC-H). ASC-US and ASC-H need to be closely monitored to prevent the development of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL). Hybrid capture 2 human papillomavirus (HC2 HPV) testing has been widely adopted for the triage of patients with ASC-US [6]. The recommendation for ASC-H is colposcopy [7]. The sensitivity of HPV testing is good; however, the high prevalence of transient HPV infections limits the specificity of this approach, resulting in high number of colposcopic referrals and unnecessary anxiety for women. Thus, there is a need for other markers, which have both high sensitivity and specificity [8-10].

The mechanisms of pathogenesis in cervical cancer are not entirely clear. Hypermethylation of CpG sites in promoter regions silences the transcription of tumor suppressor genes and is an early and crucial event in cancer development [11-13]. Inactivation of tumor suppressor genes and activation of oncogenes also play a significant role in carcinogenesis, caused by genetic and epigenetic alterations. Various genome-wide approaches have been used to discover new abnormally methylated genes for many cancers. For example, candidate methylated genes have been selected, including COL25A1 and KATNAL2, which showed increased methylation during progression in high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) lesions, to screen for the early detection of cervical cancer [14,15]. The advanced concept of using DNA methylation as a biomarker for cervical cancer screening is appealing [16-19], and several hypermethylated genes have already been identified [20]. Among them, zinc finger protein 582 (ZNF582) possesses great clinical potential [21]. ZNF582 is located on chromosome 19q13.43, which contains one KRAB-A-B domain and nine zinc-finger motifs. A recent study of acute myeloid leukemia revealed that aberrant methylation of ZNF582 is consistent in different disease subtypes, especially in the promoter region. Although the biological function of ZNF582 is not yet well characterized, a group in Taiwan found similar associations for cervical cancer and adenocarcinoma with ZNF582 using cervical scrapings. Recently, one study also revealed that hypermethylated ZNF582 (methylated ZNF582 (ZNF582m)) performs well as a marker for detecting grade III or higher cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN3+) with 73% sensitivity and 71% specificity for women with low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions [21-23].

In the present study, we examined the performance of methylated ZNF582 testing (ZNF582m) for the triage of ASC-US and ASC-H cervical scrapings and compared the results with those of HPV DNA testing.

Case description

Patient recruitment

The study was approved by the Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, People’s Republic of China. During the period between December 2011 and April 2013, women referred for a colposcopic examination were invited to participate in the study. The eligible women were sexually active, scheduled to undergo a liquid-based cytology test (LBC) within a week, not pregnant, possessed an intact uterus, and no history of treatment for CIN or cervical cancer. The exclusion criteria included women who had a history of cancer related to the reproductive tract, underwent therapy for cervical lesions, received the HPV vaccination, or were currently pregnant. Standard guidelines for the management and treatment of cervical neoplasia were followed in all subjects [24]. The cytology results were classified according to the 2001 Bethesda System [25].

After signing the informed consent, patients immediately received the colposcopic examination and biopsy. The follow-up clinical information was collected. When the biopsy results revealed moderate to severe dysplasia or worse, patients underwent conization or major surgery. The final diagnosis was based on the results of tissue-proven pathology, rather than on the LBC results. To ensure the quality control of the diagnosis, two expert cytologists and two pathologists independently read or reviewed the cytology and histology slides, respectively. All of the patient recruitment and clinical information collection processes were periodically monitored and good clinical practice (GCP) guidelines were followed.

Specimen collection and DNA preparation

All of the patients had LBC testing before receiving the colposcopic examination. After the informed consent was signed, the LBC containers (Hospitex Diagnostics SRL, Sesto Fiorentino, Italy) were picked up from the Cytology Department, and the residual cervical cells were used for HPV typing and detection of methylated ZNF582. All of the molecular tests were performed at the Institute of Clinical Pharmacology, Hunan Key Laboratory of Pharmacogenetics, China, following GLP guidelines. The cells were centrifuged and stored in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution at −20°C from the day of collection, and the assays were finished within 6 months. Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from the collected cells with a QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A BioSpec-nano spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was used to quantify the amount of extracted DNA.

DNA methylation tests

For the DNA methylation tests, quantitative methylation-specific PCR (QMSP) using TaqMan-based technologies was performed using the Lightcycler LC480 real-time PCR system (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany). Briefly, 500 ng of gDNA was subjected to bisulfite conversion using the EZ DNA Methylation-Gold™ Kit (Zymo Research, CA,USA), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

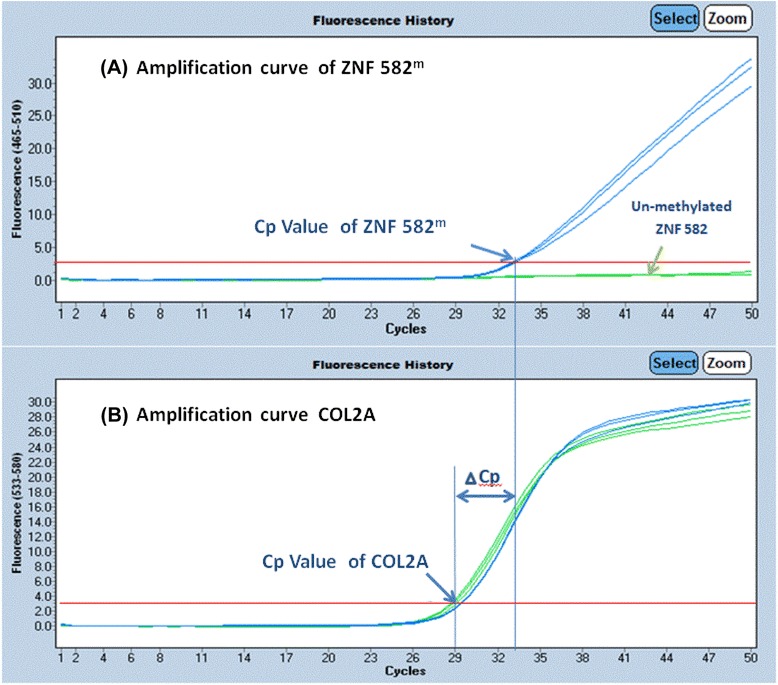

The methylation levels of ZNF582 were then determined using the qPCR kits developed by iStat Biomedical located in Taiwan. The type II collagen gene (COL2A) was designed as the internal reference and tested with each specimen. The crossing point (Cp) value for COL2A, which is also the validity indicator of the test, should not be larger than 35. The PCR cycling conditions consisted of an initial incubation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 50 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 s, and annealing/extension at 60°C for 40 s. Fluorescence data were collected during the annealing/extension step for determination of the Cp. For each sample, two Cp values were obtained: one from the target gene and another from COL2A. The DNA methylation level was subsequently determined from the difference between the two Cp values (delta Cp = CpZNF582 - CpCOL2A). ZNF582 was deemed to be hypermethylated or positive if the delta Cp was smaller than 13 (the cut-off value). The registered CaSki and A375 cancer cell lines were used as the methylation and no-methylation controls to ensure the quality of bisulfite conversion and qPCR processes. Representative positive and negative QMSP results are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Representative positive and negative ZNF582 methylation detection by real-time PCR. For each specimen, ZNF582 m (labeled with FAM) and COL2A (labeled with VIC) were detected simultaneously. Fluorescence data were collected during the annealing/extension step for determination of the crossing point (Cp). The amplification curve for ZNF582 is shown in panel (A) and the control COL2A gene is shown in panel (B). The blue arrow indicates the crossing point, and the x-axis value is the so-called Cp value. The ΔCp is the difference between Cp values for ZNF582 m and COL2A. A smaller ΔCp indicates a higher degree of methylation detected in the testing sample. ZNF582 was deemed to be hypermethylated (or positive) if the ΔCp was smaller than 13 (the cut-off value). The blue arrow is Cp value of ZNF582 m and the green arrow is the un-methylated ZNF582 m in panel (A). ZNF582, zinc finger protein 582; ZNF582 m, methylated ZNF582.

Laboratory methods for HPV DNA amplification and genotyping

High-risk human papillomavirus (HPV-HR) typing was performed using a nested multiplex PCR (NMPCR) assay that combines degenerate E6/E7 consensus primers and type-specific primers. The identification of HPV-HR was achieved by determining the size of the nested PCR amplification product [26].

Statistical analysis

The cut-off values for ZNF582m were generated from the first 100 subjects, including 50 subjects with normal Pap test results and 50 subjects with abnormal Pap test results. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) was calculated for the detection of the CIN3+ lesions.

SAS software (version 9.2) was used for all statistical analyses (SAS Institute, Ltd., Cary, NC, USA). The chi-square test was used to analyze the status of methylated ZNF582 or HPV typing in different combinations. Fisher’s exact test was used for the small number data, for example, age under 30 group analysis. For the final analysis, the sensitivity and specificity with a 95% confidence interval (CI) for grade CIN3 lesions or worse were obtained. All differences were considered two-sided and statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Discussion and evaluation

Establishment of routine Pap screening has resulted in a significant decrease in cervical cancer deaths. In China, ASC, including ASC-US and ASC-H, were reported in approximately 10% of papanicolaou smear (Pap smears) [27]. The large number of ASC patients referred for colposcopic examination and follow-up could be an extra burden. In conjunction with the currently available tests, molecular diagnostic tests that can assist in the diagnosis of cancer and that have both a high sensitivity and high specificity would be useful because they would be more accurate than Pap tests alone. Recent guidelines in the USA recommend that adult women with an ASC-US Pap result either have the Pap test repeated at 6 and 12 months, or have an HPV-HR DNA test. In China, repeated follow-up is impractical and time-consuming because many areas do not have sufficient medical resources to perform additional examinations. Another option is to send ASC patients for colposcopy, but colposcopy may not be available in the areas where patients reside thus prohibiting or delaying the diagnosis. Moreover, colposcopy is more invasive and causes anxiety to many women.

Because of the high sensitivity, triage of ASC-US with HPV-HR has been suggested in the cervical screening guidelines. This strategy provides the advantage of missing fewer cases of the severe disease state [28]. However, the low specificity still leads to approximately 50% of women with ASC-US being referred for colposcopy [29]. A similar trend was observed in the present study. The sensitivity and specificity of HPV-HR for detecting CIN3+ were 99.33% and 38.76%, respectively. Seventy-three percent (177/242) of the women with an ASC-US or ASC-H result were positive for HPV-HR, but 61.3% of them had a histological result of CIN2, CIN1, or normal, which is not indicative of a referral for a colposcopic examination. Thus, the HPV-HR test is limited by its low specificity.

In 2012, the American Cancer Society proposed new screening guidelines that included using age-adjusted screening methodologies as well as cytological and HPV co-testing. HPV 16 and 18 typing has been recommended for HPV-HR-positive women [30]. However, geographic variation in the distribution of HPV genotypes exists. In Asia, in addition to HPV types 16 and 18, types 52 and 58 are frequently observed in patients with invasive cervical cancers [31-33]. Similar trends were also observed in the present study even though the test subjects were only limited to women with ASC. In CIN3+ lesions (N = 74), HPV 16 (55.4%) and HPV 52 (31.1%) were the most common types, followed by HPV 18 (13.5%), HPV 58 (12.2%), and HPV 33 (9.4%). Among the high percentage of HPV 16 and/or 52 in the CIN3 lesions, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy are 74.32%, 73.81%, and 73.97%, respectively. Therefore, the combination of Pap smear and HPV-16/18 typing is not sufficiently accurate for cervical cancer triage in this study.

ZNF582m has been found to possess clinical potential for the detection of cancer. For example, the frequency of methylated ZNF582 detection was 100% in SCC tissue. Clinically, ZNF582m has demonstrated 70% sensitivity and 82% specificity for CIN3+ lesions in a Taiwanese case-control cohort. For triage of LSIL, ZNF582m also has good sensitivity and specificity with values of 73% and 71%, respectively. Moreover, the ZNF582m was reported at a high methylation rate in cervical adenocarcinoma, which has been difficult to diagnose.

In triage of the ASC group, CADM1/MAL, WT1, and other methylation genes have been reported [34]. The present study has proposed a new strategy: co-testing for ZNF582m and HPV-16/18, in which the patients negative for ZNF582m undergo HPV-16/18 genotyping. As mentioned, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of the co-test are 89.19%, 70.24%, and 76.03%, respectively. The colposcopy referral rate of the co-test is 47.9%, which is 25.2% less than that of HPV-HR alone. Although eight cases of CIN3+ (10.81%) were missed, nearly 100% of the women with SCC were successfully diagnosed and treated (Table 1). It is also known that the cumulative actuarial rate of progression from CIN3 (severe dysplasia) to CIS or worse is 12% in 4 to 24 months [35,36]. Thus, for patients with ASC undetected by the co-test, a regular follow-up Pap test would be highly recommended. Thus, the progression of the lesion for the eight women with undetected CIN3 would be closely monitored. This triage model would greatly reduce the cost and increase the accuracy for patients residing in countries with limited resources for colposcopy, such as China.

Table 1.

Number of colposcopies performed using different triage strategies

| Triage tests | Histological results | HPV-HR | ZNF582 m alone | ZNF582 m or HPV-16/18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| = < CIN2 | 168 | 103 (61.3%) | 39 (23.2%) | 50 (29.8%) |

| CIN3+ | 74 | 74 (100.0%) | 61 (82.4%) | 66 (89.2%) |

| SCC | 29 | 29 (100.0%) | 25 (86.2%) | 29 (100.0%) |

| Total colposcopy (referral rate) | 242 | 177 (73.1%) | 100 (41.3%) | 116 (47.9%) |

CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; HPV-HR, high-risk human papillomavirus; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; ZNF582 m, methylated ZNF582.

The subjects were recruited at the colposcopic examination room. As mentioned, women had results of abnormal pap, inflammation syndrome, cervical erosion, bedding syndromes, or suspected cervical cancer, and these women would be referred to have a colposcopic examination. In our cohort, >90% of women had inflammation syndrome with positive HPV-HR, which correlate with high percentage of CIN2+ (~45%) observed. Although it is known that heterogeneous etiology for cancers and the equivocal nature of ASC, the significance of ZNF582m in cancer detection was still being observed.

Characteristics of subjects and colposcopic biopsy results

From November 2011 to March 2013, 242 women were scheduled for colposcopic examinations. The characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 2. Generally, when women received results of an abnormal Pap, cervical erosion, or suspected cervical cancer, they would be referred to colposcopic examination room from the gynecological outpatient department (OPD). There were 199 women who had ASC-US and 43 who had ASC-H based on the LBC test. The histological and cytological results of the 242 women are shown in Table 2. In total, the colposcopy and biopsy results revealed normal histology in 109 (45.04%) patients, CIN1 in 23 (9.50%) patients, CIN2 in 36 (14.87%) patients, CIN3 in 39 (16.11%) patients, carcinoma in situ (CIS) in 6 (2.47%) patients, and invasive carcinoma in 29 (11.98%) patients. Thus, 30.6% (74 of 242) of the total patients had a histological finding of CIN3 or worse (CIN3+). Specifically, 22.1% and 70% of the patients had CIN3+ in the ASC-US and ASC-H groups, respectively.

Table 2.

Characteristics and histological results of the study subjects

| Histological results | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | CIN 1 | CIN 2 | CIN 3/CI | SCC/AC | ||

| Number of subjects | ||||||

| N | 109 | 23 | 36 | 45 | 29 | 242 |

| (%) | (45.04%) | (9.50%) | (14.88%) | (18.60%) | (11.98%) | (100%) |

| Age | 43.1 ± 10.1 (21.8 to 75.0) | |||||

| Mean age | 42.39 | 48.54 | 39.07 | 41.77 | 48.8 | 43.13 |

| (Min to max) | (22.18 to 74.97) | (28.98 to 66.17) | (21.76 to 64.57) | (27.84 to 57.00) | (33.98 to 65.14) | (21.76 to 74.97) |

| Cytology results | ||||||

| ASC-US | 103 | 20 | 32 | 29 | 15 | 199 |

| (%) | (51.75%) | (10.05%) | (16.08%) | (14.57%) | (7.53%) | (100%) |

| ASC-H | 6 | 3 | 4 | 16 | 14 | 43 |

| (%) | (13.95%) | (6.97%) | (9.30%) | (37.20%) | (32.55%) | (100%) |

| ZNF582 m | ||||||

| Number | 18 | 8 | 13 | 36 | 25 | 100 |

| (%) | (16.51%) | (34.78%) | (36.11%) | (80.00%) | (86.20%) | (41.32%) |

| HPV-HR | ||||||

| Number | 57 | 13 | 33 | 45 | 29 | 177 |

| (%) | (52.29%) | (56.52%) | (91.67%) | (100%) | (100%) | (73.14%) |

AC, adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix; ASC-H, atypical squamous cells, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions could not be excluded; ASC-US, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; CIS, carcinoma in situ; HPV-HR, high risk human papillomavirus; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Molecular test results in the detection of CIN3+: ZNF582m and HPV genotyping

The distribution of the molecular tests for different levels of disease severity is listed in Table 2. Table 3 shows the results of the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy for different molecular tests or combinations of molecular tests in different age groups for the detection of CIN3+ lesions. Among the 242 ASC subjects, 41% were positive for ZNF582m. The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of ZNF582m in the identification of CIN3+ lesion were 82.43%, 76.79%, and 78.51%, respectively. However, when the CIN2 or more severe neoplasms were targeted, the sensitivity and accuracy of ZNF582m was decreased to 67.27% and 74.38%, respectively, but the specificity was increased to 80.30%. Among women less than 30 years old with ASC, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of ZNF582m in the identification of a CIN3+ lesion were 75.00%, 81.48%, and 80.65%, respectively. For postmenopausal women with ASC, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were 88.89%, 69.77%, and 75.41%, respectively.

Table 3.

The performance of combinations of ZNF582 m and HPV tests in detecting CIN3+ in ASC

| Tests | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All ages (N = 242) | |||||

| ZNF582 m | 82.43 | 76.79 | 78.52 | 15.52 (7.73 to 31.18) | <0.001 |

| HPV-HR | 99.33 | 38.76 | 57.37 | - | <0.001 |

| HPV-16/18 | 66.22 | 88.10 | 81.41 | 14.50 (7.42 to 28.37) | <0.001 |

| ZNF582 m or HPV-16/18 | 89.19 | 70.24 | 76.03 | 19.47 (8.71 to 43.54) | <0.001 |

| ZNF582 m or HPV-16/18/52/58 | 95.95 | 48.81 | 63.22 | 14.79 (6.39 to 34.19) | <0.001 |

| ZNF582 m or HPV-HR | 99.33 | 34.02 | 54.10 | 76.84 (4.68 to 1262.62) | 0.002 |

| ZNF582 m and HPV-HR | 82.43 | 81.55 | 81.82 | - | <0.001 |

| ZNF582 m and HPV-16/18 | 59.46 | 94.64 | 83.88 | 25.91 (11.45 to 58.61) | <0.001 |

| Age under 30 (N = 31) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| ZNF582 m | 75.00 | 81.48 | 80.65 | 13.20 (1.12 to 154.92) | 0.043 |

| HPV-HR | 90.00 | 41.07 | 48.49 | - | 0.233 |

| HPV-16/18 | 75.00 | 92.59 | 90.33 | 37.50 (2.56 to 548.36) | 0.009 |

| ZNF582 m or HPV-16/18 | 75.00 | 77.78 | 77.42 | 10.50 (0.92 to 120.26) | 0.063 |

| ZNF582 m or HPV-HR | 90.00 | 37.50 | 45.46 | - | 0.274 |

| ZNF582 m and HPV-HR | 75.00 | 85.19 | 83.87 | 17.25 (1.42 to 210.12) | 0.028 |

| ZNF582 m and HPV-16/18 | 75.00 | 96.30 | 93.55 | 78.00 (3.81 to 1595.87) | 0.004 |

| Postmenopausal Women | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| ZNF582 m | 88.89 | 69.77 | 75.41 | 18.46 (3.70 to 92.14) | <0.001 |

| HPV-HR | 97.37 | 48.86 | 63.49 | - | 0.001 |

| HPV-16/18 | 88.89 | 86.05 | 86.89 | 49.33 (8.97 to 271.23) | <0.001 |

| ZNF582 m or HPV-16/18 | 97.37 | 62.50 | 73.02 | - | <0.001 |

| ZNF582 m or HPV-HR | 97.37 | 44.32 | 60.32 | - | 0.001 |

| ZNF582 m and HPV-HR | 88.89 | 74.42 | 78.69 | 23.27 (4.60 to 117.81) | <0.001 |

| ZNF582 m and HPV-16/18 | 77.78 | 93.02 | 88.52 | 46.67 (9.27 to 234.86) | <0.001 |

P values determined by chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test; CI, confidence interval; HPV, human papillomavirus; HPV-HR, high-risk human papillomavirus; OR, odds ratio for CIN3 +; ZNF582 m, methylated ZNF582.

The HPV typing indicated that 177 (73.14%) patients were positive for HPV-HR. The most common types of HPV were HPV 16 (23.14%), HPV 52 (23.14%), HPV 58 (14.88%), HPV 68 (7.85%), HPV 33 (7.44%), and HPV 18 (6.05%). The sensitivity and specificity of HPV-HR in identifying CIN3+ were 99.33% and 38.76%, respectively. The percentage of patients who were positive for HPV-16/18 and who had CIN3+ was 66.22% (49 of 74). The prevalence of HPV-16/18 in patients whose tissue was pathologically normal, CIN1, CIN2, CIN3/CIS, or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) was 7.34%, 17.39%, 22.22%, 55.56%, and 82.76%, respectively.

The results for ZNF582m combined with different HPV genotyping assays are interesting. The sensitivity of ZNF582m combined with HPV-HR, HPV-16/18/52/58, or HPV-16/18 was 99.33%, 95.98%, or 89.19%, respectively, but the specificity was increased with values of 34.02%, 48.81%, and 70.24%, respectively.

Colposcopy referral rate: the performance of ZNF582m and HPV genotyping in the triage of ASC

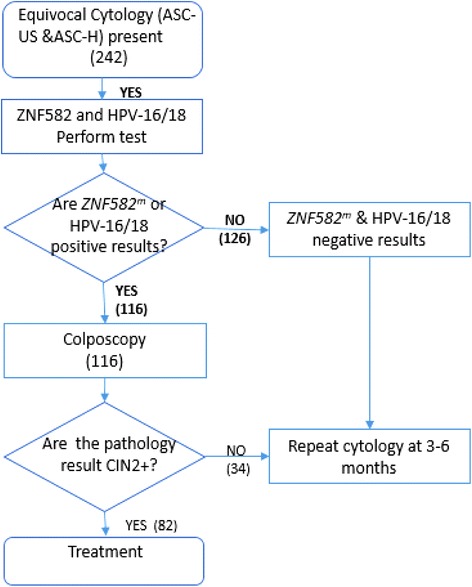

Colposcopy is a diagnostic procedure performed by a physician to examine the cervix, vagina, and vulva carefully for signs of disease. Due to the high cost and insufficient availability of colposcopy, it is desirable to reduce the number of colposcopy referrals while still examining women with severe dysplasia or carcinoma such as CIN3, CIS, or SCC. Our results indicated that the referral rate for colposcopy for ZNF582m alone, HPV-HR alone, and ZNF582m, or HPV-16/18 are 41%, 73.1%, and 47.9% respectively (Table 1). Previous research has recommended triage procedures using HPV-HR followed by gene methylation screening [34]. Using HPV-HR testing as triage identified no CIN3 and SCC results in the study but the referral rate for colposcopy is 73.1%. If triaged using ZNF582m testing alone, the colposcopy referral would therefore reduce 31.8% compared to that of HPV-HR. However, only 61 out of the 74 women with CIN3+ and 4 SCC results would be detected. As a result, no treatment would be given to 17 women, who would be in a severe disease stage, especially the four with SCC. To avoid not detecting the severe cases, we have proposed a new strategy to manage ASC patients (Figure 2). This clinical flowchart has incorporated the ZNF582m and HPV testing into the procedures. Co-testing for ZNF582m and HPV-16/18 would therefore reduce 61 cases (25.21%) from colposcopy referral (when compared with HPV-HR), yet none of the SCC cases would be missed (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The recommended management of abnormal cervical cytology (Pap smear): a flowchart with methylated ZNF582 m. ASC-H, atypical squamous cells cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; ASC-US, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2; HPV, human papillomavirus-16/18; ZNF582, zinc finger protein 582; ZNF582 m, methylated ZNF582.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to discuss the involvement of ZNF582m in the ASC group and to consider using the combination of HPV results and methylation markers in the triage of colposcopic referral. It is also the first to compare HPV genotyping and ZNF582m in the triage of women with ASC Pap smear results. Our results showed that ZNF582m could be a promising triage technique for women with ASC. We have recommended a new management strategy of abnormal cervical cytology (Pap smear) illustrated in a flowchart. The present study did have some limitations. The subjects were recruited at the colposcopic examination room. Other limitations include using a smaller sample sizes and a lack of extensive long-term follow-up information. However, our results suggest that testing for ZNF582m followed by HP-V16/18 testing could help to reduce the number of patients with ASC being referred for colposcopy. This could reduce the logistics of obtaining follow-up care, especially in regions where colposcopy is not easily available, which could have a significant impact on public health.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University. We thank the women who participated in this study and their families. We also thank Chong-Zhen Oin, Pei-Yu Lv, Ying Zhang, Na-Yi Yuan Wu, Meng-Xue Ge, Rui-Jia Li, Chun Zhang, Juan Chen, Yue-Li Zhang, and Xing-Yu for assistance with patient recruitment and the clinical information collection process.

Abbreviations

- ASC-H

Atypical squamous cells cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions

- ASC-US

Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance

- AUC

Area under the curve

- CI

Confidence interval

- CIN

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

- CIS

Carcinoma in situ

- HPV-HR

High-risk human papillomavirus

- LBC

Liquid-based cytological test

- Pap smear

Papanicolaou smear

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- SCC

Squamous cell carcinoma

- ZNF582

Zinc finger protein 582

- ZNF582m

Methylated ZNF582

Footnotes

Competing interests

iStat Co., Ltd provided the testing kits for the project. Yu-Ligh Liou is the PhD student of Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, China and an employee of iStat Biomedical Co., Ltd., Taiwan. Huei-Jen Wang and Chi-Feng Chang are employees of iStat Co., Ltd. The other authors declare that they have no potential competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YLL contributed to the writing of this manuscript, and the coordination of the clinical trial and all of the molecular tests. YLL, YuZ, CFC, TYC, YL and HHZ contributed to the conception, design, and final approval of the submitted version. YZ, LC, CZQ, and YiZ contributed to the clinical data evaluation and selection. HJW and TLZ contributed to the assay for the results. YLL and SYL contributed to the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Yu-Ligh Liou, Email: pedro.liou@gmail.com.

Yu Zhang, Email: cszhangyu@126.com.

Yingzi Liu, Email: yzliu2005@163.com.

Lanqin Cao, Email: caolanqin@163.com.

Chong-Zhen Qin, Email: 15973121956@126.com.

Tao-Lan Zhang, Email: ztl19870622@163.com.

Chi-Feng Chang, Email: cfchang@istatbio.com.

Huei-Jen Wang, Email: jen@istatbio.com.

Shu-Yi Lin, Email: crystal.miracle.yi@gmail.com.

Tang-Yuan Chu, Email: hidrchu@gmail.com.

Yi Zhang, Email: zhangyi5588@aliyun.com.

Hong-Hao Zhou, Email: hhzhou2003@163.com.

References

- 1.Li J, Kang LN, Qiao YL. Review of the cervical cancer disease burden in mainland China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1149–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao P, Dai M, Chen W, Li N. Cancer trends in China. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:281–5. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi JF, Canfell K, Lew JB, Qiao YL. The burden of cervical cancer in China: synthesis of the evidence. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:641–52. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan QJ, Hu SY, Guo HQ, Zhang WH, Zhang X, Chen W, et al. Liquid-based cytology and human papillomavirus testing: a pooled analysis using the data from 13 population-based cervical cancer screening studies from China. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133:172–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melnikow J, Nuovo J, Willan AR, Chan BK, Howell LP. Natural history of cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:727–35. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(98)00245-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arbyn M, Roelens J, Cuschieri K, Cuzick J, Szarewski A, Ratnam S, et al. The APTIMA HPV assay versus the Hybrid Capture 2 test in triage of women with ASC-US or LSIL cervical cytology: a meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:101–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barreth D, Schepansky A, Capstick V, Johnson G, Steed H, Faught W. Atypical squamous cells - cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (ASC-H): a result not to be ignored. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2006;28:1095–8. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)32330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saavedra KP, Brebi PM, Roa JC. Epigenetic alterations in preneoplastic and neoplastic lesions of the cervix. Clin Epigenetics. 2012;4:13. doi: 10.1186/1868-7083-4-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuzick J, Szarewski A, Cubie H, Hulman G, Kitchener H, Luesley D, et al. Management of women who test positive for high-risk types of human papillomavirus: the HART study. Lancet. 2003;362:1871–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14955-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Apgar BS, Brotzman G. Management of cervical cytologic abnormalities. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:1905–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lai HC, Lin YW, Huang RL, Chung MT, Wang HC, Liao YP, et al. Quantitative DNA methylation analysis detects cervical intraepithelial neoplasms type 3 and worse. Cancer. 2010;116:4266–74. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin CJ, Lai HC, Wang KH, Hsiung CA, Liu HW, Ding DC, et al. Testing for methylated PCDH10 or WT1 is superior to the HPV test in detecting severe neoplasms (CIN3 or greater) in the triage of ASC-US smear results. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:21e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sobti RC, Singh N, Hussain S, Suri V, Nijhawan R, Bharti AC, et al. Aberrant promoter methylation and loss of suppressor of cytokine signalling-1 gene expression in the development of uterine cervical carcinogenesis. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2011;34:533–43. doi: 10.1007/s13402-011-0056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farkas SA, Milutin-Gasperov N, Grce M, Nilsson TK. Genome-wide DNA methylation assay reveals novel candidate biomarker genes in cervical cancer. Epigenetics. 2013;8:1213–25. doi: 10.4161/epi.26346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lendvai A, Johannes F, Grimm C, Eijsink JJ, Wardenaar R, Volders HH, et al. Genome-wide methylation profiling identifies hypermethylated biomarkers in high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia. Epigenetics. 2012;7:1268–78. doi: 10.4161/epi.22301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wentzensen N, Sherman ME, Schiffman M, Wang SS. Utility of methylation markers in cervical cancer early detection: appraisal of the state-of-the-science. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:293–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Meide WF, Snellenberg S, Meijer CJ, Baalbergen A, Helmerhorst TJ, van der Sluis WB, et al. Promoter methylation analysis of WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway regulators to detect adenocarcinoma or its precursor lesion of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123:116–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai HC, Lin YW, Huang TH, Yan P, Huang RL, Wang HC, et al. Identification of novel DNA methylation markers in cervical cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:161–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eijsink JJ, Lendvai A, Deregowski V, Klip HG, Verpooten G, Dehaspe L, et al. A four-gene methylation marker panel as triage test in high-risk human papillomavirus positive patients. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:1861–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steenbergen RD, Snijders PJ, Heideman DA, Meijer CJ. Clinical implications of (epi) genetic changes in HPV-induced cervical precancerous lesions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:395–405. doi: 10.1038/nrc3728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang RL, Chang CC, Su PH, Chen YC, Liao YP, Wang HC, et al. Methylomic analysis identifies frequent DNA methylation of zinc finger protein 582 (ZNF582) in cervical neoplasms. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e41060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin H, Chen TC, Chang TC, Cheng YM, Chen CH, Chu TY, et al. Methylated ZNF582 gene as a marker for triage of women with Pap smear reporting low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions - a Taiwanese Gynecologic Oncology Group (TGOG) study. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;135:64–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang CC, Huang RL, Wang HC, Liao YP, Yu MH, Lai HC. High methylation rate of LMX1A, NKX6-1, PAX1, PTPRR, SOX1, and ZNF582 genes in cervical adenocarcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24:201–9. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ngan HY, Garland SM, Bhatla N, Pagliusi SR, Chan KK, Cheung AN, et al. Asia Oceania guidelines for the implementation of programs for cervical cancer prevention and control. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/794861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, Moriarty A, O’Connor D, Prey M, et al. The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA. 2002;287:2114–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin H, Moh JS, Ou YC, Shen SY, Tsai YM, ChangChien CC, et al. A simple method for the detection and genotyping of high-risk human papillomavirus using seminested polymerase chain reaction and reverse hybridization. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan QJ, Hu SY, Zhang X, Ci PW, Zhang WH, Guo HQ, et al. Pooled analysis of the performance of liquid-based cytology in population-based cervical cancer screening studies in China. Cancer Cytopathol. 2013;121:473–82. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schiffman M, Solomon D. Findings to date from the ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study (ALTS) Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:946–9. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-946-FTDFTA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study (ALTS) Group Results of a randomized trial on the management of cytology interpretations of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1383–92. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(03)00418-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, Killackey M, Kulasingam SL, Cain J, et al. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;137:516–42. doi: 10.1309/AJCPTGD94EVRSJCG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H, Zhang J, Chen Z, Zhou B, Tan Y. Prevalence of human papillomavirus genotypes among women in Hunan province, China. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;170:202–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quek SC, Lim BK, Domingo E, Soon R, Park JS, Vu TN, et al. Human papillomavirus type distribution in invasive cervical cancer and high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia across 5 countries in Asia. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23:148–56. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31827670fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen CA, Liu CY, Chou HH, Chou CY, Ho CM, Twu NF, et al. The distribution and differential risks of human papillomavirus genotypes in cervical preinvasive lesions: a Taiwan cooperative oncologic group study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:1801–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Strooper LM, Hesselink AT, Berkhof J, Meijer CJ, Snijders PJ, Steenbergen RD, et al. Combined CADM1/MAL methylation and cytology testing for colposcopy triage of high-risk HPV-positive women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:1933–7. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holowaty P, Miller AB, Rohan T, To T. Natural history of dysplasia of the uterine cervix. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:252–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.3.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCaffery K, Waller J, Forrest S, Cadman L, Szarewski A, Wardle J. Testing positive for human papillomavirus in routine cervical screening: examination of psychosocial impact. BJOG. 2004;111:1437–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]