Abstract

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) have been reported to enhance synaptic plasticity and improve cognitive performance in adult rats. SERMs have also been shown to induce neuroprotection against cerebral ischemia and other CNS insults. In this study, we sought to determine whether acute regulation of neurogenesis and spine remodeling could be a novel mechanism associated with neuroprotection induced by SERMs following cerebral ischemia. Toward this end, ovariectomized adult female rats were either implanted with pellets of 17β-estradiol (estrogen) or tamoxifen, or injected with raloxifene. After one week, cerebral ischemia was induced by the transient middle-cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) method. Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) was injected to label dividing cells in brain. We analyzed neurogenesis and spine density at day-1 and day-5 post MCAO. In agreement with earlier findings, we observed a robust induction of neurogenesis in the ipsilateral subventricular zone (SVZ) of both the intact as well as ovariectomized female rats following MCAO. Interestingly, neurogenesis in the ipsilateral SVZ following ischemia was significantly higher in estrogen and raloxifene-treated animals compared to placebo-treated rats. In contrast, this enhancing effect on neurogenesis was not observed in tamoxifen-treated rats. Finally, both SERMs, as well as estrogen significantly reversed the spine density loss observed in the ischemic cortex at day-5 post ischemia. Taken, together these results reveal a profound structural remodeling potential of SERMs in the brain following cerebral ischemia.

Keywords: Raloxifene, Tamoxifen, Estrogen, Cerebral Cortex, Neurogenesis, Plasticity, Cerebral Ischemia

INTRODUCTION

Selective estrogen receptors modulators (SERMs) are a class of compounds, which act as agonists or antagonists to estrogen receptors (ERs) depending on the tissue types. Two well-studied SERMs are tamoxifen and raloxifene; which were initially designed for the treatment of breast cancer and osteoporosis, respectively. However, a number of studies suggest that tamoxifen and raloxifene can have neuroprotective effects in vitro or in vivo against neurological insults or in neurological disorders [1–11]. Additionally, both tamoxifen and raloxifene have also been shown to enhance memory, cognition, and synaptic plasticity in various experimental studies [12, 13]. However the mechanisms underlying the beneficial neural effects of SERMs are still unclear. Findings from our group and others suggest that tamoxifen can exert neuroprotection by regulating kinase signaling pathways, antioxidant enzymes, and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation [7, 9]. In contrast, the mechanisms of raloxifene neuroprotection have not been studied in detail and are poorly understood. It is known that tamoxifen and raloxifene can recruit different coactivators or corepressors to the ER complex, which may account, in part, for the well known divergent effects of the SERMs in some tissues.

Under various experimental conditions, 17β-estradiol (E2) is known to prevent cell death, promote neuronal survival, and enhance synaptic plasticity in the brain [14–20]. In addition, a number of studies have shown that E2 can enhance neurogenesis, leading to production of new neurons in the affected cerebral hemisphere [21–23]. New neurons are produced from the neural progenitor cells (NPCs) residing along the lateral wall of subventricular zone (SVZ) in the forebrain and the dentate gyrus of hippocampus [24–26]. In the forebrain, a majority of NPCs from the SVZ have been shown to migrate toward the sites of injury, including the cortex and striatum [27–29]. The SVZ-derived NPCs differentiate into mature neurons at the sites of injury and form synapses with neighboring cells [30]. These findings suggest that estradiol plays an important trophic as well as neuroprotective role in the adult brain. However, findings from the Women’ Health Initiative suggested that estrogens, under some circumstances, might actually increase the risk of neurodegeneration [31–33]. While this finding is controversial, it has increased the search for alternative estrogenic compounds that possess minimal negative side effects, while retaining beneficial neural effects.

In the current study, we sought to examine whether clinically relevant SERMs can regulate neurogenesis and spine density in the brain as mechanisms to reduce brain injury and enhance neural repair following focal cerebral ischemia in ovariectomized female rats. For comparison, the effects of estrogen were also examined. Since the SVZ can be a source of new neurons after focal cerebral ischemia [27–29], we examined the effect of clinically relevant doses of the SERMs, tamoxifen and raloxifene (as well as estrogen) on neurogenesis and spine density in the affected cerebral hemisphere following transient and permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) in ovariectomized female rats. The results suggest that estrogen and raloxifene enhance neurogenesis in the ipsilateral SVZ following MCAO. Tamoxifen, on the other hand had no significant effect on neurogenesis in the SVZ. Interestingly, all three compounds significantly reduced ischemia-induced spine density loss in the ipsilateral cortex following MCAO. These findings provide evidence for a potential role of estrogen and SERMs in cortical remodeling following ischemic brain injury.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals and drug treatment

All experiments were conducted in compliance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of experimental animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Sixty-day-old Holtzman Sprague Dawley female rats (Harlan, IN) were used for the study. The animals were housed in individual cages and water and rat chow was provided ad libitum. The animals were bilaterally ovariectomized and implanted subcutaneous (sc) in the mid-upper back region with pellets that contained placebo, E2 (0.025 mg which produces low diestrus [10–15pg/ml] levels of E2) [34] or tamoxifen (15 mg pellets, which releases ~1 mg/kg/d of tamoxifen) [9]. In addition, an additional group of ovariectomized rats were injected intramuscularly with raloxifene at a daily dose of 10 mg/kg. One week later, all animals underwent surgery to induce cerebral ischemia as described below.

Induction of cerebral ischemia

Focal cerebral ischemia was induced using the transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) method as described previously by our laboratory (9). Briefly, rats were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (intramuscular, 60 mg/ml and 8 mg/ml, respectiv ely). A thermal blanket was used to maintain body temperature at 37°C. The skin of the neck was shaved and swabbed with betadine, and an incision was made directly on top of the right common carotid artery region. The fascia was then blunt dissected until the bifurcation of the external common carotid artery and internal common carotid artery was isolated. A small incision was made in the external common carotid artery and then a 4-0 monofilament suture pretreated with poly-l-lysine (18.5–19.5 mm long with a round tip) was threaded into the internal common carotid artery via the external common carotid artery. The suture was then advanced toward the middle cerebral artery to create cerebral ischemia. The suture was removed at 30min post ischemia. Animals were sacrificed at different time intervals after MCAO as described in the figure legends.

BrdU Incorporation

The dividing neural stem cells (NSCs) were labeled using 5-bromo-deoxyuridine (5′-BrdU) at a concentration of 50mg/kg/d of the body weight. BrdU was dissolved in 0.1M NaOH solution followed by dilution in PBS, pH 7.4. BrdU was injected starting one hour before ischemia followed by two injections daily for five days (see scheme in Figure 1A). Animals were sacrificed 24 h after the last BrdU injection. To see the acute effect of estrogen, tamoxifen and raloxifene on the regulation of neurogenesis; five animals from each treatment group were sacrificed after day-5 post ischemia. Some animals from each treatment group were also sacrificed at day-1 post ischemia.

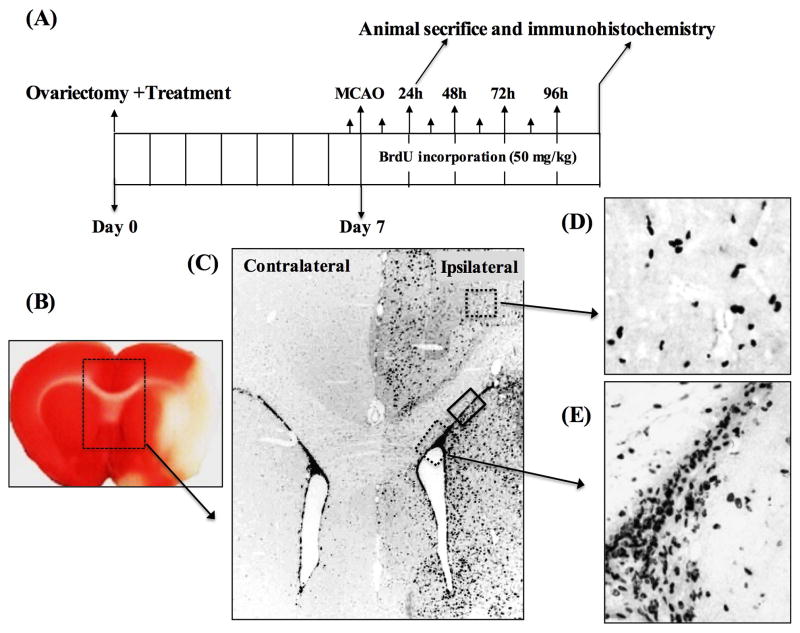

Figure 1. Ischemia induces neurogenesis in the SVZ of ovariectomized female rats.

A) Shows the experimental design for the neurogenesis experiments. Animals were ovariectomized and E2 or SERM treatment initiated immediately. MCAO was performed one week later. BrdU (50 mg/kg, ip) was injected 15 min prior to MCAO followed by two BrdU injections daily for 96 h post MCAO. Animals were sacrificed at day-1 and day-5 post MCAO and processed for immunohistochemistry. B), a TTC stained coronal section of the brain showing the development of infarct at 24h (day-1) post MCAO. The box region illustrates the contralateral and ipsilateral lateral ventricles (SVZ), which was magnified to see the pattern of NPCs proliferation in response to ischemia. C) Shows the DAB staining pattern of BrdU+ cells in the contralateral and ipsilateral SVZ from a placebo-treated animal at day-5 post MCAO. The box regions depict the areas of ipsilateral cortex (upper dashed box) and the ipsilateral ventral SVZ (lower dotted box) and the dorsal SVZ (solid box) of the ipsilateral hemisphere showing the migration of BrdU+ cells following MCAO. D and E) show the larger views of DAB staining pattern of BrdU+ cells detected in ipsilateral cortex and ventral SVZ regions, respectively.

Perfusion and fixation

Animals were deeply anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and transcardially perfused with saline followed by fixation with 300–400 ml ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.4, at a flow rate of 20–25 ml/min. After fixation, brain samples were cut into 5-mm blocks and placed in the fixative overnight at 4°C followed by cryoprotection in 30% sucrose solution in 0.1 M PB, pH 7.4 at 4°C until the brains permeated. Tissue was frozen in OCT (optimum cutting temperature) compound under an atmosphere of nitrogen, and coronal sections (40-μm thickness) were cut on a cryostat microtome (Leica, Germany) through the entire brain and stored in a cryoprotection solution (FD Neurotechnology, Inc., Baltimore, MD) in stereological order.

2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining

To detect the infarct area caused by MCAO, TTC staining was performed at day-1 (24h) post MCAO as described previously by our group [9]. Animals were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and transcardially perfused with PBS. Brains were removed and sectioned coronally at 2-mm intervals using a brain matrix (Braintree Scientific Inc., Braintree, MA). Brain slices were placed in a Petri dish in TTC using a 2% wt/vol solution in PBS. TTC stains the viable brain tissue as red, whereas the infarcted area fails to take up the stain and remains white. The brain slices were then fixed by immersion in 2% paraformaldehyde solution and photographs were taken.

Diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining

For the staining of BrdU+ cells using the DAB method, 40-μm frozen coronal sections were incubated with 1.5N HCl at 37°C for 1h to denature the DNA. Afterward sections were washed with PBS containing 0.04% Triton-100 (PBS-T) and incubated with 10% normal serum for 1h at room temperature to block nonspecific staining. Sections were then incubated with primary mouse monoclonal anti-BrdU antibodies at a 1:1000 dilution in PBS-T for 1–2h at room temperature. Sections were then washed with PBS-T followed by incubation with secondary anti-mouse antibodies (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA) at a dilution of 1:200 in PBS-T for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were then washed with PBS-T, followed by incubation with ABC reagents for 1 h at room temperature in the same buffer. Tissue sections were then washed and incubated with DAB reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Vector Laboratories, Inc.).

Double immunofluorescence staining

For double immunofluorescence staining, 40-μm frozen coronal sections were incubated with 1.5N HCl in water bath at 37°C for 1h to denature the DNA. Afterward, sections were washed with PBS containing 0.04% Triton-100 (PBS-T) and incubated with 10% normal donkey serum for 1h at room temperature to block nonspecific surfaces. Sections were then incubated with a mixture of primary mouse monoclonal anti-BrdU antibodies and rabbit polyclonal anti-Doublecortin (Chemicon), anti-NeuN (Chemicon) or anti-GFAP (Abcam) antibodies at appropriate dilution in PBS-T for 1–2h at room temperature. Afterward, sections were washed with PBS-T followed by incubation with Alexa-Fluor488 donkey anti-mouse IgG and Alexa Fluor594 donkey anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (1:500) for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were washed with PBS-T 3×10 min, followed by 2×5 min with PBS and 2×1 min with water, and then mounted with water-based mounting medium containing anti-fading agents (Biomeda, Fischer Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). A simultaneous examination of negative controls (after blocking the primary antibody with peptide antigen in five to six molar excess or after omitting the primary antibodies) confirmed the absence of nonspecific immunofluorescence staining, cross-immunostaining, or fluorescence bleed through.

Confocal microscopy and image analysis

Photomicrographs of the brain sections stained by the DAB method were captured on an Axiophot-2 visible/fluorescence microscope using an AxioVision4Ac software system (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). All fluorescent-labeled images were captured on a LSM 510 258 Meta confocal laser microscope using 63X objective lens. An argon/2 laser was used for the excitation of Alexa Fluor488 (EX max: 592 nm) with the emission filters set in the wavelength range of 505–530 nm. A HeNe1 laser was used for the excitation of Alexa Fluor594 (EX max: 550 nm) with the emission filter set in the wavelength range of 568–615 nm. For each section, typically 20–30 Z-stacks (optical slices) were collected at a thickness of 0.5 – 1.0μm using optimum pinhole diameter. The Z-stacks were then converted into 3D projection image using LSM 5 Image Examiner (Carl Zeiss, Germany). The number of double-labeled cells were counted using Volocity 4 software (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, PA).

Spinophilin silver-enhanced nanogold labeling

Spinophilin silver-enhanced nanogold labeling was performed as described previously by our group [18]. Briefly, sections were thoroughly rinsed first in PBS only followed by PBS containing 0.4% Triton- X100. Sections were then incubated in a solution containing 0.1% cold water fish gelatin, 0.5% BSA, and 5% normal donkey serum diluted in PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 at room temperature for 2 h followed by incubation with a well characterized rabbit polyclonal anti-spinophilin antibody (1:10,000; Upstate Biotechnology) for 48 h at 4° C. Sections were washed with PBS containing 0.1% Tri- ton-X100 and incubated with a gold-labeled secondary antibody (1:200; donkey-anti-rabbit IgG, ultra-small; Aurion, Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hartfield, PA) for 3 h at room temperature. Sections were washed with PBS containing 0.1% Triton-X100 and with PBS only, followed by post fixation with 2% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. After post-fixation, sections were washed in PBS followed by water and treated with silver enhancement reagent as recommended by the manufacturer. Sections were dehydrated in graded alcohol, cleared in xylene, mounted, and analyzed for spine density.

Stereology

The quantitative analyses of spine density and the number of BrdU+ cells in the selected groups of animals was performed using a computer-assisted Stereology system equipped with an Olympus microscope, a computer-controlled motorized stage, and the StereoInvestigator morphometry and stereology software (MicroBrightfield, Williston, VT, USA). This procedure provides an unbiased, efficient sampling technique, and thus ultimately estimates the counts of puncta/cell population. Our group [18, 35] and others [36, 37] have used this technique previously to measure cells and spine density in the rodent brain. Identical regions from the penumbra of the ischemic cortex were selected in all the animal groups and the contours were traced at 4X magnification. Optical dissector counting frames were placed in a systematic, random fashion in the delineated regions with constant interval in the x and y-axes. The x and y distances between sampling fraction was (1.5 μm × 1.5 μm)/(100 μm × 150 μm). A 100X oil-immersion objective with 1.5X magnification lens were used for the counting of spinophilin-labeled-puncta, and a 63X oil-immersion objective was used to count the BrdU+ cells. A 2 μm “guard zone” was place at the top surface of the section. Counting was performed with the optical dissector technique through a depth of 10 μm (height of dissector). The total number of cells and spine counts (gold grains) in each region were calculated and used to determine differences between groups.

Statistical analysis

The data was analyzed using Graf pad Prism6 software. Differences between the groups were tested using ANOVA with Kruskal Wallis posttest and the values were reported as means ± SE. For confirmation, paired or unpaired t tests with Mann-Whitney posttest, or Wilcoxon test were also applied when two groups analyzed individually for statistical significance. A P <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Ischemia induces robust neurogenesis in the SVZ

Focal cerebral ischemia has been reported to induce robust proliferation of neural progenitor cells (NPCs) in the ipsilateral SVZ reaching peak at days 5–7 post MCAO. In the current study, we investigated neurogenesis in the SVZ at day-1 and day-5 post MCAO of placebo-treated ovariectomized animals by measuring the density of BrdU+ cells. Figure 1B shows a TTC stained section that demonstrates the development of the cerebral ischemia infarct at day-1 post MCAO. Figure 1C shows the DAB staining pattern of BrdU+ cells in the contralateral and ipsilateral SVZ from a placebo-treated animal at day-5 post MCAO. As shown in Figure 1C, proliferation of NPCs was significantly increased in response to ischemia in the ipsilateral SVZ, but not in the contralateral SVZ. Enhanced proliferation of NPCs in response to ischemia was also observed as early as day-1 post MCAO (data not shown). The box regions in Figure 1C indicate the areas of ipsilateral cortex (upper dashed box), ventral SVZ (lower dotted box) and the dorsal SVZ (solid box) in the ipsilateral hemisphere showing the migration of BrdU+ cells following MCAO. Figure 1D and 1E show the larger views of DAB staining pattern of BrdU+ cells detected in ipsilateral cortex and ventral SVZ regions, respectively.

Figure 2A and 2B show the patterns of BrdU+ cells in the contralateral and ipsilateral dorsal SVZ at day-1 and day-5 post MCAO, respectively. Figure 2C shows the pattern of BrdU+ cells in the ipsilateral cortex at day-1 and day-5 post MCAO. Figure 2D shows the statistical analysis of the number of BrdU+ cells from the contralateral and ipsilateral dorsal SVZ and cortex at day-1 and day-5 post MCAO. As can be seen in Figure 2, at day-1 post MCAO the number of BrdU+ cells was significantly (P<0.0001) increased in the ipsilateral dorsal SVZ (Figure 2A and Figure 2D; grey bar 2) compared to the contralateral dorsal SVZ (Figure 2A and Figure 2D; light bar 1) or sham animals (data not shown). These observations suggest that ischemic brain injury enhances neurogenesis in the SVZ of the ischemic hemisphere only. When examined at day-5 post MCAO, the number of BrdU+ cells was comparable (P= 0.065) in both the ipsilateral dorsal SVZ (Figure 2B and Figure 2D; grey bar 4) and contralateral dorsal SVZ (Figure 2B and Figure 2D; light bar 3), which indicate that the majority of BrdU+ cells may have migrated from ipsilateral SVZ to the nearby injured cortex and striatum. In support of this, a large number of BrdU+ cells were observed in these areas in the ipsilateral hemisphere, but not in the contralateral hemisphere. A statistical analysis of BrdU+ cells from the cortex at day-1 and day-5 post MCAO is presented in Figure 2D (bars 5–8). As shown in Figure 2D, the ipsilateral cortex (Figure 2C and Figure 2D; grey bars 6 and 8), had significantly higher number of BrdU+ cells both at day-1 and day-5 post MCAO as compared to the contralateral cortex (Figure 2D, light bars 5 and 7). Furthermore, the migration of NPCs from the ipsilateral SVZ to the ipsilateral cortex in response to ischemia was progressive because, the density of BrdU+ cells present in the ipsilateral cortex at day-1 (Figure 2C and Figure 2D; grey bar 6) was significantly increased at day-5 post MCAO (Figure 2C and Figure 2D; grey bar 8).

Figure 2. Ischemia progressively increases neurogenesis in the ipsilateral hemisphere only.

A and B) show the density of BrdU+ cells in the contralateral and ipsilateral dorsal SVZ at day-1 and day-5 post MCAO, respectively. C) Shows, the density of BrdU+ cells in the ipsilateral cortex at day-1 and day-5 post MCAO. D) Shows the statistical analysis of the number of BrdU+ cells from the contralateral and ipsilateral dorsal SVZ and cortex at day-1 (n=3) and day-5 post MCAO (n=5). At day-1 post MCAO, the number of BrdU+ cells was significantly (P<0.0001) increased in the ipsilateral dorsal SVZ (Figure 2A and 2D) as compared to the contralateral dorsal SVZ. At day-5 post MCAO the number of BrdU+ cells was comparable (P= 0.065) in both the ipsilateral dorsal SVZ (Figure 2B and Figure 2D) and contralateral dorsal SVZ. A statistical analysis of BrdU+ cells from the cortex at day-1 and day-5 post MCAO suggest that compared to contralateral cortex (Figure 2D), ipsilateral cortex (Figure 2C and Figure 2D), had significantly higher number of BrdU+ cells both at day-1 and day-5 post MCAO. The migration of NPCs to the ipsilateral cortex in response to ischemia was progressive because the density of BrdU+ cells present in the ipsilateral cortex at day-1 (Figure 2C and Figure 2D) was greatly increased at day-5 post MCAO.

Estrogen and raloxifene but not tamoxifen enhance neurogenesis following MCAO

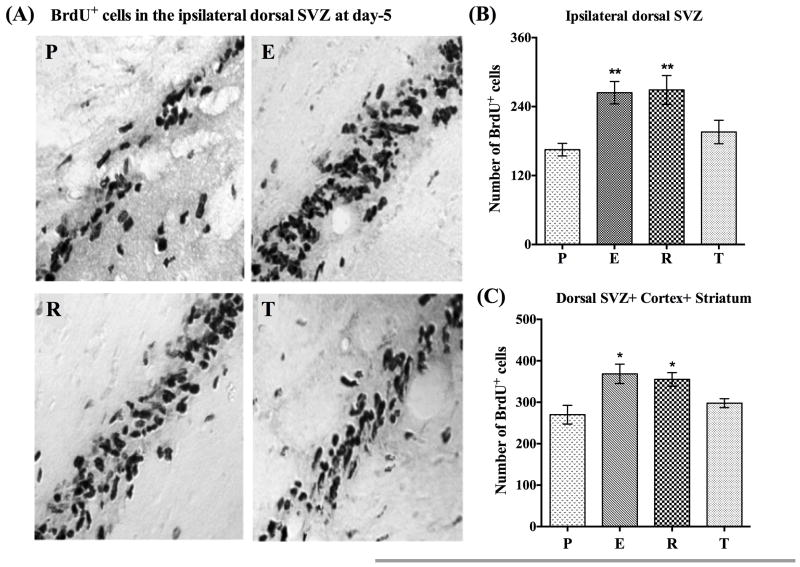

There is growing evidence that estrogen enhances ischemia-induced neurogenesis in the ipsilateral SVZ in ovariectomized female rats. We thus sought to examine whether raloxifene and tamoxifen can likewise regulate neurogenesis following ischemic brain injury in ovariectomized rats. To answer this question we investigated the effects of clinically relevant doses of raloxifene and tamoxifen, along with low dose estrogen on the rate of neurogenesis in the dorsal SVZ of the ipsilateral hemisphere at day-1 and day-5 post MCAO. The dorsal region of SVZ was selected because previous studies have shown that estrogen significantly enhances BrdU+ cells in the most dorsal SVZ after MCAO [22, 23, 38]. Figure 3A, shows light microscopic pictures of BrdU+ cells from the ipsilateral dorsal SVZ of placebo (P)-, estrogen (E)-, raloxifene (R)-, and tamoxifen (T)-treated animals at day-5 post MCAO. As can be seen in Figure 3A, when compared to placebo-treated animals (Figure 3A, panel P), both estrogen (Figure 3A, panel E) and raloxifene (Figure 3A, panel R)-treated animals appeared to have an increased number of BrdU+ cells in the dorsal SVZ, while tamoxifen-treated animals showed little to no increase (Figure 3A, panel T). Further, to determine if significance differences were indeed present, a detailed statistical analysis of BrdU+ cells from the ipsilateral dorsal SVZ from different treatment groups at day-5 post MCAO was conducted, and the results are shown in the Figure 3B. As can be seen from the Figure 3B, when compared to placebo-treated animals (Figure 3B, bar P), estrogen- (Figure 3B, bar E) and raloxifene- (Figure 3B, bar R) treated animals had a significantly (P<0.0001) higher number of BrdU+ cells in the ipsilateral dorsal SVZ. In contrast, there was no significant increase in the number of BrdU+ cells at day-5 post MCAO in tamoxifen-treated animals (Figure 3B, bar T). Additionally, when BrdU+ cells were counted in the contralateral dorsal SVZ at day-5 post MCAO, no significant differences were found between the different treatment groups (data not shown). These results suggest that estrogen and raloxifene positively regulate neurogenesis in the SVZ of the ipsilateral hemisphere.

Figure 3. Estrogen and raloxifene but not tamoxifen enhance neurogenesis following MCAO.

A), shows the light microscopic pictures of BrdU+ cells from the ipsilateral dorsal SVZ of placebo (P), estrogen (E), raloxifene (R) and tamoxifen (T) treated animals at day-5 post MCAO. Pictures clearly indicate that compared to placebo-treated animals (Figure 3A, panel P), both estrogen (Figure 3A, panel E) and raloxifene (Figure 3A, panel R) treated animals had higher number of BrdU+ cells compared to tamoxifen treated animals (Figure 3A, panel T). B) Shows a detailed statistical analysis of BrdU+ cells made from the ipsilateral dorsal SVZ from different treatment groups at day-5 post MCAO. Note that compared to placebo animals (Figure 3B, bar P, n=5), estrogen (Figure 3B, bar E, n=6) and raloxifene (Figure 3B, bar R, n=4) treated animals had significantly (P<0.0001) higher number of BrdU+ cells in the ipsilateral dorsal SVZ, whereas; tamoxifen (Figure 3B, bar T, n=5) treated animals did not shown any significant (P>0.05) increase in the the number of BrdU+ cells at day-5 post MCAO. C) Shows a cumulative statistical analysis of BrdU+ cells from identical regions of ipsilateral dorsal SVZ, cortex and striatum from each animal in different treatment groups. The analysis suggest that compared to placebo (Figure 3C, bar P), estrogen (Figure 3C; bar E) and raloxifene (Figure 3C; bar R) treated animals has significantly (P =0.025–0.009) higher number of BrdU+ positive cells in the ipsilateral hemisphere. Tamoxifen treatment (Figure 3C, bar T) did not have a significant effect (P>0.05).

To determine if estrogen and raloxifene also enhance the number of BrdU+ cells in the ipsilateral cortex and striatum, we made a statistical analysis of the number of BrdU+ cells from the identical neocortical and striatal regions from different treatment groups at day-5 post MCAO. While the density of BrdU+ cells in these regions appeared to be higher in estrogen- and raloxifene-treated animals, the effect was not statistically significant. We therefore made a cumulative statistical analysis by summing up the number of BrdU+ cells from identical regions of dorsal SVZ, cortex and striatum from each animal in different treatment groups. As can be seen in Figure 3C, when compared to placebo- (Figure 3C, bar P), estrogen- (Figure 3C; bar E) and raloxifene- (Figure 3C; bar R) treated animals show a significantly higher number of BrdU+ positive cells in the ipsilateral hemisphere (P =0.025–0.009). In contrast, there was no significant increase in tamoxifen-treated animals (Figure 3C; bar T) as compared to placebo-treated animals (Figure 3C; bar P). Furthermore, a detailed statistical analysis of BrdU+ cells from the ipsilateral dorsal SVZ at day-1 post MCAO did not reveal any significant difference between different treatment groups (data not shown). The above neurogenesis-enhancing potential of estrogen and raloxifene was also confirmed in the permanent MCAO (pMCAO) model as well (data not shown), which suggest that irrespective of the severity of ischemic brain injury, the neurogenesis-enhancing potential of estrogen and raloxifene is preserved.

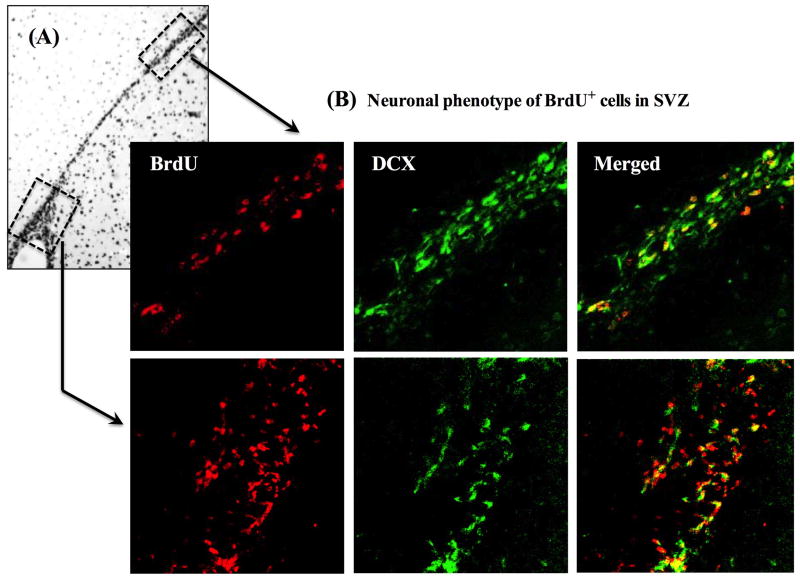

Neuronal phenotypes of NPCs during migration in the SVZ

We next analyzed whether the migrating NPCs after MCAO display a neuronal phenotype by assessing whether BrdU+ cells express doublecortin (DCX), a microtubule-associated protein that is expressed in immature and migrating neurons. Figure 4A shows a representative light microscopic photo of BrdU+ cells migrating from ventral SVZ (lower box) to the dorsal SVZ (upper box) in the ipsilateral hemisphere at day-5 post MCAO. Figure 4B shows confocal images of BrdU co-localization with DCX in the SVZ of a placebo-treated animal at day-5 post MCAO. First, the entire SVZ was traced at low magnification, and then the ventral and dorsal regions of SVZ were magnified using 63X objective lens. As shown in Figure 4B (lower panel), there is low colocalization (20–30%) of BrdU+ cells with DCX in the ventral SVZ and the intensity of DCX expression is also low. In contrast, >90% of the BrdU+ cells in the dorsal SVZ show DCX co-localization, and the intensity of DCX expression is also much higher than in the ventral SVZ (Figure 4B). Altogether, these results suggest that the DCX expression gradually increases in the BrdU+ NPCs migrating from ventral to the dorsal SVZ, and support earlier findings on the expression specificity of DCX in immature migrating neurons.

Figure 4. Neural progenitor cells (NPCs) show neuronal phenotypes during migration in the SVZ.

A) Shows a representative light microscopic picture of BrdU+ cells migrating from ventral SVZ (lower box) to the dorsal SVZ (upper box) in the ipsilateral hemisphere at day-5 post MCAO. B) Shows 3D confocal images of BrdU co-localization with doublecortin (DCX) in the SVZ of a placebo-treated animal at day-5 post MCAO. As can be seen from the lower panel, in the ventral SVZ nearly 20–30% BrdU+ cells show co-localization with DCX and the intensity of DCX expression is also low. But in the dorsal SVZ (upper panel) >90% BrdU+ cells show DCX co-localization and the intensity of DCX expression is also increased.

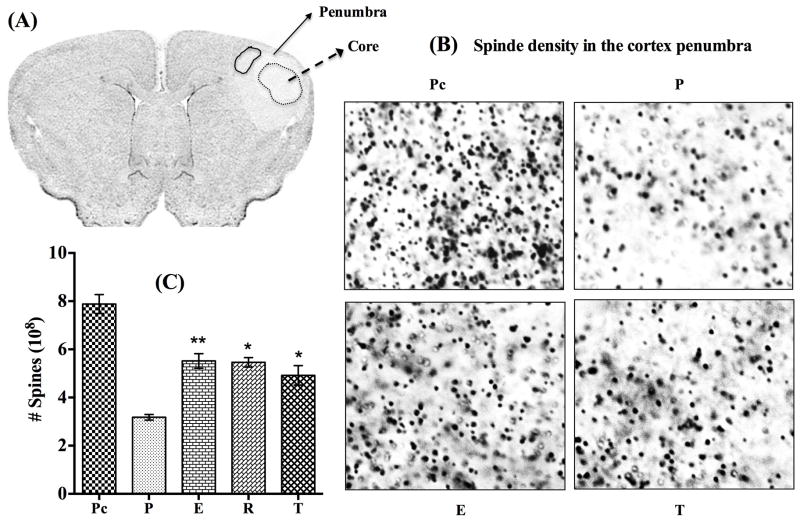

Estrogen, raloxifene and tamoxifen regulate spine density in the ischemic cortex

In clinical practice, findings in stroke patients suggest that a gradual behavioral recovery may be attributed to the anatomical and functional recovery of the penumbra region. Furthermore, behavioral recovery after cortical infarction in animal studies has been associated with neuronal sprouting followed by synaptogenesis [39, 40]. We therefore examined whether tamoxifen and raloxifene can promote brain structural plasticity in the ipsilateral cortex following MCAO. The effect of low dose estrogen was also examined. To accomplish this goal, we utilized spinophilin immunogold labeling, a widely used method to measure spine density [18, 19, 41]. Spine density changes were analyzed in the ischemic penumbra region around the core in the ipsilateral cortex at day-5 post MCAO. Figure 5A shows a coronal section illustrating the regions of core (broken circle) and penumbra in the ipsilateral hemisphere. The solid circle in the penumbra indicates the regions where the spine density was measured in all the animals. Photomicrographs shown in Figure 5B represent spinophilin labeling density from the sham (not shown) or contralateral cortex of placebo (Figure 5B; panel Pc), and the ipsilateral penumbra cortex of placebo- (Figure 5B; panel P), estrogen- (Figure 5B; panel E), and tamoxifen- (Figure 5B; panel T) treated animals at day-5 post MCAO. Stereological analysis of the number of spines from the delineated penumbra cortex of the treatment groups is presented in Figure 5C. There was a drastic reduction (P<0.0001) in the spine density in the ipsilateral penumbra of placebo-treated animals compared to that on the contralateral cortex (Figure 5B; panel P and Figure 5C; bar P) at day-5 post MCAO. Further, the spine density was significantly (P<0.022–0.01) increased in the estrogen- (Figure 5B; panel E and Figure 5C; bar E), raloxifene- (Figure 5C; bar R), and tamoxifen- (Figure 5B; panel T and Figure 5C; bar T) treated animals at day-5 post MCAO. These results demonstrate that raloxifene and tamoxifen along with estrogen may potentially restore spine density losses in the ischemic penumbra cortex following MCAO.

Figure 5. Estrogen, raloxifene and tamoxifen preserve spine density in the cortex after cerebral ischemia.

A) Shows a coronal section illustrating the probable regions of core (broken circle) and penumbra, the region around the core in the ipsilateral hemisphere. The solid circle in the penumbra (Figure 5A) indicates the regions where the spine density was measured in all the animals. B) Show photomicrographs of spinophilin density from the contralateral cortex of placebo (Figure 5B; panel Pc), and the ipsilateral penumbra cortex of placebo (Figure 5B; panel P), estrogen (Figure 5B; panel E), and tamoxifen (Figure 5B; panel T) treated animals at day-5 post MCAO. C) Shows stereological analysis of the number of spines from the delineated penumbra cortex of different treatment groups. Stereological results suggest that compared to the contralateral cortex of placebo animals (Figure 5B; panel Pc, and Figure 5C; bar Pc, n=5) there was a drastic reduction (P<0.0001) in the spine density in the ipsilateral penumbra of placebo-treated animals (Figure 5B; panel P and Figure 5C; bar P, n=5) at day-5 post MCAO. The spine density was significantly (P<0.022–0.01) increased (preserved) in the estrogen (Figure 5B; panel E and Figure 5C; bar E, n=4), raloxifene (Figure 5C; bar R, n=4), and tamoxifen (Figure 5B; panel T and Figure 5C; bar T, n=5)-treated animals at day-5 post MCAO.

DISCUSSION

Estrogen and SERM Regulation of Neurogenesis after Stroke

To our knowledge, this is the first report on the regulation of neurogenesis and spine density by raloxifene and tamoxifen following MCAO-induced brain injury. Raloxifene, but not tamoxifen was found to enhance neurogenesis in the ipsilateral SVZ following MCAO. Low dose estrogen treatment also induced a significant enhancement of neurogenesis in the ipsilateral SVZ at day 5 after MCAO, which is in agreement with previous reports that estrogen increases neurogenesis in the ipsilateral SVZ at 4–7 days, and persists up to 14 days post MCAO [21–23]. It is currently unclear as to why raloxifene, but not tamoxifen, was able to enhance neurogenesis in the SVZ after MCAO. The dose of tamoxifen used in our study (1 mg/kg/day) yields a therapeutically relevant level of tamoxifen, and we previously demonstrated this dose to be neuroprotective against MCAO [9]. However, it is possible that a higher dose of tamoxifen may be needed to modulate neurogenesis. It is also possible that different recruitment of coactivators and/or corepressors to the ER complex by raloxifene and tamoxifen could underlie the divergent neurogenic effects of the SERMs. Another, potential explanation could be the expression of estrogen receptors (ERs) in the SVZ cells. Findings from previous studies suggest that both ERα and ERβ are expressed in SVZ cells [42]. Of the two ERs, ERα expression was reported to be much higher in the proliferating SVZ cells as compared to ERβ. Since, compared to tamoxifen, raloxifene has higher affinity for ERα than ERβ, this could also potentially explain why raloxifene, but not tamoxifen increased neurogenesis after MCAO. Further studies are needed to explore this issue.

It is well known that neural progenitor cells (NPCs) are self-renewing cells with the potential to generate, neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. Furthermore, the majority of the cells in the SVZ are NPCs, as evidenced by their lack of colocalization with mature neuron-specific and astrocyte-specific markers, and colocalization of doublecortin, a marker of migrating immature neurons [24, 25, 43]. In our double immunofluorescence studies, ~20–30% of BrdU+ cells co-localized doublecortin in the lower or ventral SVZ, whereas; >90% BrdU+ cells co-localized doublecortin in the most dorsal region of SVZ. This suggests that the majority of migrating NPCs progressively acquire a neuronal phenotype before leaving the proliferating zone. Evidence also exists that the newly formed cells can migrate to areas of injury such as striatum and cortex, and become functional neurons [27–29]. We also observed a robust migration of NPCs to the injured regions, as evidenced by the finding that at both day-1 and day-5 post MCAO a large number of BrdU+ cells were present in the cortex and striatum of the ischemic ipsilateral hemisphere, as compared to very few or no BrdU+ cells seen in the non-ischemic or contralateral hemisphere. Furthermore, in the ipsilateral hemisphere, we observed a progressive migration of NPCs to the injured cortex and striatum, as the density of BrdU+ cells in these regions at day-5 post MCAO was much higher compared to the density of BrdU+ cells observed at day-1 post MCAO. Furthermore, E2 and raloxifene treatment enhanced the number of BrdU+ cells in the ipsilateral hemisphere at 5 days after MCAO.

Currently, the molecular mechanisms underlying raloxifene and estrogen regulation of neurogenesis in the SVZ after cerebral ischemia remain poorly understood. It is possible that these effects involve regulation of growth factors, which have been implicated in the control of neurogenesis. However, studies to explore this possibility are currently lacking, and more studies are clearly needed to gain molecular insights into the neurogenic effects of estrogen and raloxifene. Studies are also needed to determine whether the neurogenesis enhancing effect of raloxifene translates into improved functional outcome after stroke. While this has already been shown to be the case for estrogen, comparative behavioral outcome studies for raloxifene are lacking. However, a raloxifene analogue, LY353381.HCl, has been shown to be neuroprotective against MCAO in the rat [44], and thus raloxifene or its analogues could potentially enhance functional outcome similar to estrogen. Further studies are needed to address this issue.

Estrogen and SERM Regulation of Spine Density in the Brain after Stroke

Another important observation of this study was that raloxifene, tamoxifen and estrogen were all capable of significantly reversing the ischemia-induced spine density loss that occurred in the cerebral cortex after MCAO. It is well known that many neurons in the penumbra lose their dendritic spines in an attempt to survive after cerebral ischemia [45, 46]. Along these lines, dendritic arbor shortening has been reported in the ischemic penumbra in the first weeks following MCAO with further loss of dendritic branches after the first month in cortical pyramidal cells [47]. Another study showed that synaptic density steadily decreased up to one week following global cerebral ischemia [48]. In agreement with these studies, we also observed a significant reduction in spine density in the ischemic cortex of placebo-treated animals at day-5 post MCAO. Interestingly, estrogen-, tamoxifen- and raloxifene-treated animals displayed significantly higher (preserved) spine density in the ischemic penumbra cortex as compared to placebo-treated animals at day-5 post MCAO. To our knowledge, this is the first report that SERMs can enhance spine density in the ipsilateral cortex after focal cerebral ischemia. While functional outcomes were not addressed in the current study, the findings nevertheless suggest that SERMs may have the capacity to enhance structural and behavioral recovery following ischemic brain injury. In support of this possibility, both raloxifene and tamoxifen have been reported to acutely enhance spine density in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex of normal non-ischemic male rats, an effect that was correlated with enhanced allocentric working memory [12, 13]. The molecular mechanisms underlying raloxifene and tamoxifen regulation of sine density in the cerebral cortex is currently unclear. However, in a previous study, we found that estrogen enhanced excitatory synapse formation in cortical neurons via a rapid extranuclear ER-mediated signaling mechanism that involves up-regulation of AMPA receptor GluR1 subunit and mediation by Akt and ERK signaling pathways [18]. It is thus possible that raloxifene and tamoxifen may use a similar mechanism to enhance plasticity in the brain after cerebral ischemia. Further studies are needed on this issue.

In conclusion, the current study demonstrates that estrogen and SERMs have significant reparative and structural preserving potential in the brain following ischemic injury. These findings provide further support that SERMs may have potential efficacy for treatment of neurological disorders, and thus are worthy of continued study.

Highlights.

Estradiol and Raloxifene enhanced neurogenesis in the subventricular zone after focal cerebral ischemia

Tamoxifen did not enhance neurogenesis after focal cerebral ischemia

Estradiol, Raloxifene and Tamoxifen all enhanced spine density in the cerebral cortex after focal cerebral ischemia

The study demonstrates a profound structural remodeling potential of estradiol and SERMs in the brain following cerebral ischemia

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Research Grant (NS050730) from the National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, USA.

Abbreviations

- BrdU

5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine

- CNS

central nervous system

- DCX

doublecortin

- E2

17β-Estradiol

- ER

estrogen receptor

- MCAO

middle cerebral artery occlusion

- NPCs

neural progenitor cells

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- SERM

selective estrogen receptor modulator

- SVZ

subventricular zone

- TTC

3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kokiko ON, Murashov AK, Hoane MR. Administration of raloxifene reduces sensorimotor and working memory deficits following traumatic brain injury. Behav Brain Res. 2006;170:233–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morissette M, Al Sweidi S, Callier S, Di Paolo T. Estrogen and SERM neuroprotection in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;290:60–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biewenga E, Cabell L, Audesirk T. Estradiol and raloxifene protect cultured SN4741 neurons against oxidative stress. Neuroscience letters. 2005;373:179–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Neill K, Chen S, Brinton RD. Impact of the selective estrogen receptor modulator, raloxifene, on neuronal survival and outgrowth following toxic insults associated with aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2004;185:63–80. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciriza I, Carrero P, Azcoitia I, Lundeen SG, Garcia-Segura LM. Selective estrogen receptor modulators protect hippocampal neurons from kainic acid excitotoxicity: differences with the effect of estradiol. J Neurobiol. 2004;61:209–21. doi: 10.1002/neu.20043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callier S, Morissette M, Grandbois M, Pelaprat D, Di Paolo T. Neuroprotective properties of 17beta-estradiol, progesterone, and raloxifene in MPTP C57Bl/6 mice. Synapse. 2001;41:131–8. doi: 10.1002/syn.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee ES, Yin Z, Milatovic D, Jiang H, Aschner M. Estrogen and tamoxifen protect against Mn-induced toxicity in rat cortical primary cultures of neurons and astrocytes. Toxicol Sci. 2009;110:156–67. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma K, Mehra RD. Long-term administration of estrogen or tamoxifen to ovariectomized rats affords neuroprotection to hippocampal neurons by modulating the expression of Bcl-2 and Bax. Brain research. 2008;1204:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.01.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wakade C, Khan MM, De Sevilla LM, Zhang QG, Mahesh VB, Brann DW. Tamoxifen neuroprotection in cerebral ischemia involves attenuation of kinase activation and superoxide production and potentiation of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase. Endocrinology. 2008;149:367–79. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Jin Y, Behr MJ, Feustel PJ, Morrison JP, Kimelberg HK. Behavioral and histological neuroprotection by tamoxifen after reversible focal cerebral ischemia. Exp Neurol. 2005;196:41–6. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arevalo MA, Santos-Galindo M, Lagunas N, Azcoitia I, Garcia-Segura LM. Selective estrogen receptor modulators as brain therapeutic agents. Journal of molecular endocrinology. 2011;46:R1–9. doi: 10.1677/JME-10-0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Velazquez-Zamora DA, Garcia-Segura LM, Gonzalez-Burgos I. Effects of selective estrogen receptor modulators on allocentric working memory performance and on dendritic spines in medial prefrontal cortex pyramidal neurons of ovariectomized rats. Horm Behav. 2012;61:512–7. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez-Burgos I, Rivera-Cervantes MC, Velazquez-Zamora DA, Feria-Velasco A, Garcia-Segura LM. Selective estrogen receptor modulators regulate dendritic spine plasticity in the hippocampus of male rats. Neural Plast. 2012;2012:309494. doi: 10.1155/2012/309494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott E, Zhang QG, Wang R, Vadlamudi R, Brann D. Estrogen neuroprotection and the critical period hypothesis. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology. 2012;33:85–104. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brann DW, Dhandapani K, Wakade C, Mahesh VB, Khan MM. Neurotrophic and neuroprotective actions of estrogen: basic mechanisms and clinical implications. Steroids. 2007;72:381–405. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simpkins JW, Singh M, Brock C, Etgen AM. Neuroprotection and estrogen receptors. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;96:119–30. doi: 10.1159/000338409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubal DB, Kashon ML, Pettigrew LC, Ren JM, Finklestein SP, Rau SW, et al. Estradiol protects against ischemic injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:1253–8. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199811000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan MM, Dhandapani KM, Zhang QG, Brann DW. Estrogen regulation of spine density and excitatory synapses in rat prefrontal and somatosensory cerebral cortex. Steroids. 2013;78:614–23. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang Y, Janssen WG, Hao J, Roberts JA, McKay H, Lasley B, et al. Estrogen replacement increases spinophilin-immunoreactive spine number in the prefrontal cortex of female rhesus monkeys. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:215–23. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy DD, Segal M. Regulation of dendritic spine density in cultured rat hippocampal neurons by steroid hormones. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:4059–68. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-13-04059.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown CM, Suzuki S, Jelks KA, Wise PM. Estradiol is a potent protective, restorative, and trophic factor after brain injury. Seminars in reproductive medicine. 2009;27:240–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1216277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J, Siegel M, Yuan M, Zeng Z, Finnucan L, Persky R, et al. Estrogen enhances neurogenesis and behavioral recovery after stroke. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism. 2011;31:413–25. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki S, Gerhold LM, Bottner M, Rau SW, Dela Cruz C, Yang E, et al. Estradiol enhances neurogenesis following ischemic stroke through estrogen receptors alpha and beta. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2007;500:1064–75. doi: 10.1002/cne.21240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gross CG. Neurogenesis in the adult brain: death of a dogma. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2000;1:67–73. doi: 10.1038/35036235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gage FH. Neurogenesis in the adult brain. Journal of neuroscience. 2002;22:612–3. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00612.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alvarez-Buylla A, Garcia-Verdugo JM. Neurogenesis in adult subventricular zone. The Journal of neuroscience. 2002;22:629–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00629.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arvidsson A, Collin T, Kirik D, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O. Neuronal replacement from endogenous precursors in the adult brain after stroke. Nat Med. 2002;8:963–70. doi: 10.1038/nm747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin K, Sun Y, Xie L, Peel A, Mao XO, Batteur S, et al. Directed migration of neuronal precursors into the ischemic cerebral cortex and striatum. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;24:171–89. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goings GE, Sahni V, Szele FG. Migration patterns of subventricular zone cells in adult mice change after cerebral cortex injury. Brain research. 2004;996:213–26. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamashita T, Ninomiya M, Hernandez Acosta P, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Sunabori T, Sakaguchi M, et al. Subventricular zone-derived neuroblasts migrate and differentiate into mature neurons in the post-stroke adult striatum. The Journal of neuroscience. 2006;26:6627–36. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0149-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shumaker SA, Legault C, Rapp SR, Thal L, Wallace RB, Ockene JK, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2651–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.20.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wassertheil-Smoller S, Hendrix SL, Limacher M, Heiss G, Kooperberg C, Baird A, et al. Effect of estrogen plus progestin on stroke in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2673–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.20.2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rapp SR, Espeland MA, Shumaker SA, Henderson VW, Brunner RL, Manson JE, et al. Effect of estrogen plus progestin on global cognitive function in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2663–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.20.2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang QG, Han D, Wang RM, Dong Y, Yang F, Vadlamudi RK, et al. C terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein (CHIP)-mediated degradation of hippocampal estrogen receptor-alpha and the critical period hypothesis of estrogen neuroprotection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:E617–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104391108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang QG, Laird MD, Han D, Nguyen K, Scott E, Dong Y, et al. Critical role of NADPH oxidase in neuronal oxidative damage and microglia activation following traumatic brain injury. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacobsen JS, Wu CC, Redwine JM, Comery TA, Arias R, Bowlby M, et al. Early-onset behavioral and synaptic deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:5161–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600948103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Praag H, Kempermann G, Gage FH. Running increases cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:266–70. doi: 10.1038/6368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng J, Zhang P, Li X, Lei S, Li W, He X, et al. Post-stroke estradiol treatment enhances neurogenesis in the subventricular zone of rats after permanent focal cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience. 2013;231:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun MK, Hongpaisan J, Nelson TJ, Alkon DL. Poststroke neuronal rescue and synaptogenesis mediated in vivo by protein kinase C in adult brains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:13620–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805952105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang ZG, Chopp M. Neurorestorative therapies for stroke: underlying mechanisms and translation to the clinic. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:491–500. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70061-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allen PB, Ouimet CC, Greengard P. Spinophilin, a novel protein phosphatase 1 binding protein localized to dendritic spines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:9956–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Isgor C, Watson SJ. Estrogen receptor alpha and beta mRNA expressions by proliferating and differentiating cells in the adult rat dentate gyrus and subventricular zone. Neuroscience. 2005;134:847–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Couillard-Despres S, Winner B, Schaubeck S, Aigner R, Vroemen M, Weidner N, et al. Doublecortin expression levels in adult brain reflect neurogenesis. The European journal of neuroscience. 2005;21:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rossberg MI, Murphy SJ, Traystman RJ, Hurn PD. LY353381.HCl, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, and experimental stroke. Stroke. 2000;31:3041–6. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.12.3041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benowitz LI, Carmichael ST. Promoting axonal rewiring to improve outcome after stroke. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;37:259–66. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown CE, Wong C, Murphy TH. Rapid morphologic plasticity of peri-infarct dendritic spines after focal ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2008;39:1286–91. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.498238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mostany R, Portera-Cailliau C. Absence of large-scale dendritic plasticity of layer 5 pyramidal neurons in peri-infarct cortex. The Journal of neuroscience. 2011;31:1734–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4386-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sulkowski G, Struzynska L, Lenkiewicz A, Rafalowska U. Changes of cytoskeletal proteins in ischaemic brain under cardiac arrest and reperfusion conditions. Folia Neuropathol. 2006;44:133–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]