Abstract

Background

Accounting for patient views and context is essential in evaluating and improving patient-centered care initiatives, yet few studies have examined the patient perspective. In the Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System, several VA facilities have transitioned from traditionally disease- or problem-based care to patient-centered care. We used photovoice to explore perceptions and experiences related to patient-centered care among Veterans receiving care in VA facilities that have implemented patient-centered care initiatives.

Design

Participants were provided prompts to facilitate their photography, and were asked to capture salient features in their environment that may describe their experiences and perceptions related to patient-centered care. Follow-up interviews were conducted with each participant to learn more about their photographs and intended meanings. Participant demographic data were also collected.

Results

Twenty-two Veteran patients (n=22) across two VA sites participated in the photovoice protocol. Participants defined patient-centered care broadly as caring for a person as a whole while accommodating for individual needs and concerns. Participant-generated photography and interview data revealed various contextual factors influencing patient-centered care perceptions, including patient-provider communication and relationships, physical and social environments of care, and accessibility of care.

Conclusions

This study contributes to the growing knowledge base around patient views and preferences regarding their care, care quality, and environments of care. Factors that shaped patient-centered care perceptions and the patient experience included communication with providers and staff, décor and signage, accessibility and transportation, programs and services offered, and informational resources. Our findings may be integrated into system redesign innovations and care design strategies that embody what is most meaningful to patients.

1.0 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

Patient-centered care represents comprehensive, high-quality health care tailored around patient needs [1–3]. Cornerstones include engaging patients and families in clinical decisions, respecting patient preferences and needs, enhancing access to health services and improving communication between patients and health care staff [4–5]. Patient-centered care is associated with improved quality of care, patient satisfaction and health outcomes, as well as reductions in health care disparities and costs [6–8].

Studies show that patient-centered care initiatives may be particularly beneficial in meeting the clinical needs and expectations of Veteran patients [9–11]. In the Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System, several VA facilities have transitioned from traditionally disease- or problem-based care, to patient-centered care through implementing innovations that focus on the whole person, not just the disease. Such innovations include providing complementary/alternative therapies, enhancing preferred options for care access and information [12–13] and creating healing environments through noise reduction, music and art.

Effectively implementing patient-centered care requires a thorough evaluation of its impact on patients, including an understanding of patients’ perceptions [14–15]. In an analysis of health care organizations that implemented patient-centered care initiatives, Luxford and colleagues found that going beyond conventional frameworks to engage patients was essential [16]. Evaluations of patient-centered care initiatives are needed that go beyond system levels to consider patients’ unique views. To this end, innovative new approaches need to be used to evaluate the effects of patient-centered care innovations.

Photovoice is a participatory evaluation method that has been used by researchers to understand patient perceptions of chronic illnesses and to promote patient engagement [17–18]. In this method, participants take photographs of meaningful elements in their environment, such as objects, landscapes, and events. The photographs are intended to stimulate dialogue and create a platform for participants to share their unique narrative [19] on a particular topic. Pioneering studies have found this technique beneficial in (1) extracting rich data that identifies participants’ needs and perceptions, and (2) empowering participants to engage in their own health and health care [20–21].

In the VA, True and Fritch found that photovoice was a helpful tool for returning Veterans to share personal narratives and communicate their health care needs [22]. One study to date has used photovoice to explore patients’ perspectives of clinical care processes. The authors explored perceptions of patients with brain injury, and concluded that using photovoice in clinical settings was effective in improving patient-provider communication and patient engagement [23].

Given the importance of patient perceptions and engagement in patient-centered care quality, using photovoice to understand the Veteran patient perspective may be especially useful as the VA transitions to a patient-centered care model.

1.2 Project Objectives

The purpose of this project was to use photovoice to explore perceptions and experiences related to patient-centered care among Veterans receiving care in VA facilities that have implemented patient-centered care initiatives. Specifically, we aimed to:

understand how patients conceptualize patient-centered care;

examine the contextual elements that drive these perspectives; and

assess the benefits of using photovoice to explore perceptions of patient-centered care.

2.0 METHODS

2.1 Design

Data collection and participant recruitment took place at two VA health care facilities that were early adopters of patient-centered care innovations. These VA facilities focused on general care and primary care areas and were located in two different states. Data were collected and analyzed in 2013, and may have encompassed various innovations implemented in the VA since 2010. A convenience sample of Veteran participants was recruited via flyers and invitation letters distributed locally at each of the two VA facilities.

This project was conducted as part of a quality improvement effort by VA health care facilities to evaluate and understand patient-centered care using participatory methods that explore patient perspectives.

2.2 Data Collection

Potential participants attended a 30 minute informational orientation session held at their VA facility to learn about the project goals and procedures. Each interested participant received a five megapixel digital camera, a two gigabyte secure digital memory card, ethical training (e.g., no faces in photos) and instructions for participation.

Participants were asked to take 25–30 photographs that capture salient features in their environment using the following prompts:

Take a photograph of what matters most to you, with regard to your health.

Take a photograph of something the VA has done to incorporate or consider your needs and preferences as a patient.

Take a photograph of something that represents an area where the VA has not incorporated or considered your needs and preferences.

Technical training was provided to ensure that participants were comfortable with using a digital camera and taking photographs. Participants had 4 weeks to take the photographs. After the participants took their photographs, they returned the memory card to the evaluation team using VA business reply envelopes.

Participants who took and shared their photographs were invited to partake in a 30 to 60-minute one-on-one follow-up interview at their respective VA facility. These interviews were scheduled approximately 8 weeks from the date of the orientation. A semi-structured interview guide was developed for this project that was guided by the Social Ecological Model to explore individual-, environmental- and system-level factors shaping patients’ perceptions [24].

During the interview, the photovoice researcher and participant used the photographs to stimulate discussion. The researcher probed into the significance of each photograph in order to elicit detailed personal narratives about experiences with and perceptions of patient-centered care. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis.

2.3 Data Analysis

Interview data were entered into Nvivo 8 (QSR International Ltd., 2008) for coding and analysis. An inductive coding approach was used for analysis. Coding was conducted by two qualitative research experts across three rounds to finalize emerging themes. During the first round, the two coders independently reviewed three transcripts to develop a preliminary code list. The coders then collaboratively created a list of codes and coded six transcripts independently and together refined the code definitions. The final list of codes was applied to remaining transcripts. Discrepancies were reconciled through consensus. Coded transcripts were analyzed within and across cases to develop themes.

3.0 RESULTS

Of the 38 Veterans approached for recruitment, twenty-two Veteran patients (n=22) across the two VA sites participated in all phases of the photovoice protocol, representing a 58% participation rate. Median age among participants was 58 years, and 18 participants (81.8%) were male. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient demographic characteristics.

| n = 22 Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Gender | |

| Male | 18 (81.8) |

| Female | 4 (18.2) |

| Age | |

| Mean: 57.7 years | |

| Median: 58 years | |

| Range: 39–71 years | |

| 18–49 years | 3 (13.6) |

| 50–64 years | 14 (63.6) |

| 65+ years | 5 (22.7) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 7 (31.8) |

| African American/Black | 14 (63.6) |

| Asian American | 1 (4.5) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 3 (13.6) |

| Divorced or separated | 9 (40.9) |

| Widowed | 3 (13.6) |

| Never married | 7 (31.8) |

| Health Status | |

| Excellent | 1 (4.5) |

| Very good | 5 (22.7) |

| Good | 8 (36.4) |

| Fair | 7 (31.8) |

| Poor | 1 (4.5) |

| Education Completed | |

| Did not complete elementary school | 0 (0) |

| Elementary (grades 1 through 8) | 0 (0) |

| Some high school (grades 9 through 11) | 3 (13.6) |

| High school graduate (grade 12 or GED) | 6 (27.3) |

| Some college or technical school | 11 (50.0) |

| College graduate (4 years or more) | 2 (9.1) |

In general, participants defined patient-centered care broadly as caring for a person as a whole while accommodating for individual needs and concerns. Most believed that patient-centered care meant receiving the best possible care in a setting where providers and staff are courteous, considerate, and always put the patient first. Data were grouped into three themes that described the key factors influencing participants’ perceptions of patient-centered care.

3.1 People, Places and System-level Factors

3.1.1 People

VA staff, providers and other Veterans played a key role in participants’ perceptions of patient-centered care. Participants believed that these people shaped the quality of their care.

For most participants, interactions with VA providers and staff drove their perceptions of their care. Generally, participants felt that VA providers and staff genuinely cared about patients. Participants favored a sense of friendship when interacting with physicians and other providers.

“I like to have that [friend] kind of relationship with whatever doctor I’m with… the doctors here that I have, you know, they’ll sit and talk with you. They show a lot of concern.” (Male, 58)

Many highlighted that communication with providers was essential, and that a need existed for patients to work actively with providers to address patient health concerns. Participants appreciated providers who spent more time with patients, and provided explanations regarding medications, treatment and outcomes.

“They explain everything to you…tell you what the outcome might be [with] the medicine they give you… what kind of reaction you might get from it… they try to be more helpful.” (Male, 55)

One participant described a photograph of his cane (Figure 1) as a representation of his care at the VA.

Fig. 1. Photograph of patient’s walking cane.

“That’s my cane, yep. You know it just kind of symbolizes the little care that was provided for me… For some people it may be nothing, but it’s like one more little thing provided.” (Male, 49)

Shared experiences, social support, and opportunities to socialize with Veterans helped to shape perceptions of patient-centered care. Many participants described feeling a sense of moral support in interacting with other Veterans, and appreciated VA spaces designed for Veterans to socialize. One participant reflected on the Veteran camaraderie:

“We may have not been driving the same car, but we’ve been down the same road.” (Male, 58)

Participants believed that socializing with other Veterans at the VA had a positive impact on their patient experience. One participant noted about his own social involvement with Veterans at the VA:

“It helps with my mental state, it does. It really relaxes me.” (Male, 57)

At an individual level, participants described their own role and a sense of personal responsibility in patient-centered care. Many perceived patient-centered care as a collective effort of patients and providers. One participant commented on the patient’s role in the patient-centered care experience:

“You have to work with them… you can’t expect them to be miracle workers. If you don’t tell them what’s going on with you, they can’t diagnose it. You got to let them know... what problems you’re having, what the symptoms are, and they take care of you.” (Male, 62)

Being an informed and empowered patient was important to participants, some of whom felt that patient-centered care was also about providing patients with tools to enhance their own health care experience. When asked about efforts that participants take to actively improve their own health, Veterans discussed lifestyle changes they had made, including eating healthier, exercising, enrolling in VA health and wellness programs, and following doctors’ recommendations.

3.1.2. Places

The physical environment greatly affected participants’ perceptions of the care they received within the VA system. Participants reported mixed experiences with transportation to and from VA facilities. One participant noted:

“They’re always improving, providing special needs for Vets… like transportation going from one hospital to another, which is great.” (Male, 53)

Veterans living further away from public transport reported challenges in coming to the VA for medical appointments. These participants shared their dissatisfaction with the time it took to reach the VA for routine visits. Several participants also commented on the difficulty in finding parking at their VA facility and the length of time to reach the facility once parked. Participants suggested that VA shuttle buses could be operated more frequently for patient convenience.

Our sample responded positively toward steps that assist with patient navigation within VA facilities. Participants found that the availability of staff members to escort and direct Veterans around the VA was helpful. Additionally, many participants appreciated signage at VA campuses, indicating that conveniently located signs, indoors and outdoors, allowed for a smoother, more efficient process in accessing care.

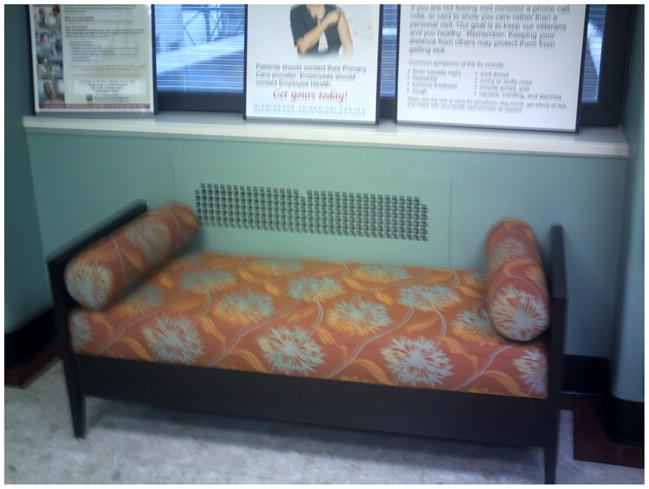

Accessibility around the VA was important to participants. Many preferred to see indications of accessibility at their VA, even if they did not require accessibility support. The availability of wheelchairs was one area of accessibility that participants commented on. Participants discussed the importance of accessible bathrooms, doors, railings and ramps. Participants also commented on places to sit around the VA (Figure 2). Some felt that hallways and other common areas could offer more seating for Veterans; others were mostly satisfied with the availability of chairs. One participant reflected on the presence of handrails and ramps placed around the VA to assist Veterans using canes or wheelchairs (Figure 3).

Fig. 2. Photograph of a bench.

“[The VA] put these [benches] right there by the elevator… which is highly important. Sometimes it takes a minute for the elevator to get there and they’ve got that [bench] on every floor now… couldn’t ask for any better than that.” (Male, 62)

Fig. 3. Picture of ramp and handrails.

“This is a ramp… where [Veterans] can walk, and they have the hand rails… and there are little inserts in there, if you need to stop you can put your cane here, or your wheelchair up against those.” (Female, 66)

Artwork and other displays were commonly photographed and admired by participants. These included exhibits of Veteran honors and medals, VA hospital awards, local artwork and history, flags and patriotic symbols. One participant reflected on his photographs depicting VA displays to recognize deceased Veterans:

“This photograph here is honoring the Vets… that have passed, you know, the heroes… and I really like that.” (Male, 68)

Participants also appreciated health messages posted around the VA, commenting that it was important to use compassion while keeping Veterans informed about important health issues.

Many highlighted the importance of peaceful spaces around their VA. The presence of wellness areas and meditation gardens that create a comforting atmosphere was a significant part of the patient experience. These spaces included aesthetic elements such as plants and photographs of nature, as well as soft music. Participants noted that these places offered a unique space designed for Veterans to take a deep breath and relax (Figure 4).

Fig. 4. Photograph of indoor meditation garden.

“[Veterans] sit down and meditate and you know, a piano plays, so, a lot of times that helps, you know, with stressful situations, to be somewhere where you can go and just… take a deep breath and breathe in, so that’s a positive thing for me.” (Female, 45)

Participants also felt that an ambience of comfort was important in patient waiting areas. Another participant observed:

“[here is] a major waiting room, but very comfortable, I mean it’s like being at home… when you go, you’re like in a more livable, relaxed environment…who wants to be stressed out when they’re sick.” (Male, 53)

3.1.3 System-level Factors

Participants identified various system-level factors that shaped their patient-centered care perceptions. In accessing care, participants reported that a common challenge was dealing with long wait times to see their providers in clinic waiting rooms and in scheduling appointments. Some believed that over-crowding in clinics took up too much of the providers’ time, and resulted in long wait times for patients. One participant stated:

“When you got over-crowding, you’re not getting the care you need.” (Male, 62)

Many felt that pharmacy wait times to collect medications were also long, but appreciated efforts to make the process more efficient.

One participant referred to a TV screen in the pharmacy area indicating if a patient’s prescription was ready for pick-up:

“It’s in a waiting room, and… it posts when your medicines are ready…which is very helpful.” (Male, 53)

Other participants found that a phone-based VA system to order medications useful.

Most participants were involved with and enjoyed VA support programs designed especially for Veterans. These included Veteran peer support groups, social activities, exercise and wellness programs, housing support, substance and alcohol abuse and rehabilitation support groups. While participants valued the availability of such programs, many noted that they often learned about them through other Veterans, instead of VA staff and providers.

“Some of the old timers know a great deal about what’s available to them, and then newcomers… need to be educated. Sometimes they get information from other Veterans, not necessarily from the department.” (Male, 65)

Although information gaps about these programs existed, many Veterans used word-of-mouth communication to disseminate information to others. One participant stated the following about Veterans sharing information about support programs:

“It really helps… and makes [Veterans] feel a lot better because now they know what to do… I pass on the information that was given to me by somebody else.” (Male, 62)

Participants also appreciated VA volunteer service programs that allowed Veterans to serve their own VA community. One participant, an active volunteer, took a photograph of one of her volunteer activities, distributing water to Veterans (Figure 5).

Fig. 5. Picture of water with sliced lemon.

“I pass out water [to other Veterans]. It’s relaxing, it’s something to do and, the people appreciate it.” (Female, 51)

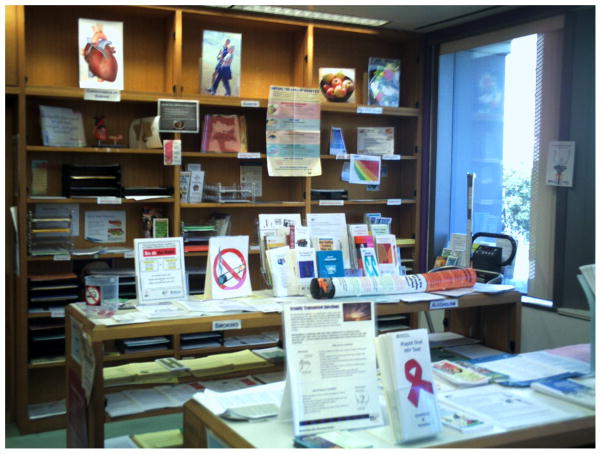

Accessible patient informational materials were also important for participants. Many wanted to be informed about Veterans’ health issues, and appreciated library resources and electronic services to access information and communicate with providers at their VA facility. One participant took a photograph of patient informational resources available at the VA (Figure 6), and commented on the need for accessible patient information. Another participant stated:

“They have computers out there so you’re able to log in. They have a medical website you can log into and get your information or update it. It’s one way of communicating back and forth with the nurse or doctor or something like that. That’s great, because if you need to know something… like far as medical or… something I can find out through them what I need to do.” (male, 53)

Fig. 6. Photograph of informational materials for patients.

“They have all their information out there.” (Male, 53)

3. 2 The Photovoice Experience

Participants responded positively towards using photovoice to describe their perceptions of patient-centered care. Although many participants had little experience with using digital cameras, most were quickly able to operate the camera’s basic functions and capture clear images. One participant commented:

“I didn’t think it was going to be that easy to do but… it was.” (Male, 68)

Several participants indicated that they preferred visually illustrating their own experiences and views related to patient-centered care at their VA facility, instead of describing them through words alone. One participant stated:

“A photograph is worth a thousand words, and it’s easier for me to explain it by showing you a photograph than just say that I like what the VA has to offer.” (Male, 57)

Another participant explained:

“I enjoyed this better, because… when you write, another person might translate it different. But this way, it’s right here, it’s a visual, and I like that we were able to go out and do these visually, and bring back… our concerns.” (Female, 66)

Others noted that they liked engaging in the photovoice method because it was beneficial to reflect on their own perspective, and provided a platform to share their views with other Veterans and the VA community. One participant commented:

“It became interesting to really just be able to reflect on things that I feel like it’s important to me to be able to share with somebody else.” (Female, 45)

Most participants felt that they enjoyed the project and said they would participate again in a similar activity.

4.0 DISCUSSION

Accounting for unique patient needs and engaging patients in their own care and decision-making are essential components of patient-centered care [4, 25]. Yet, few qualitative studies have examined the patient viewpoint in the context of patient-centered care. Use of the photovoice methodology gave us an opportunity to focus on this key area, allowing us to conduct an in-depth, rich exploration of patient perspectives of patient-centered care. Our findings contribute to the growing knowledge base around patient views and preferences, and may be integrated into system redesign innovations and care design strategies that embody what is most meaningful to patients.

Application of participatory methodologies, such as photovoice, to patient-centered care is a new concept [23], and we found it to be useful in multiple ways. First, photovoice provided an innovative platform to broadly understand the Veteran patient perspective related to patient-centered care. Additionally, it was helpful in identifying specific needs, preferences and values that shape patient perceptions. Furthermore, photovoice was valuable in stimulating dialogue and engaging patients in a qualitative evaluation of patient-centered care.

Prior research shows that patient participation in medical care is a function of personal, provider-level, and system-level factors [26–27]. Our findings indicate that patients view patient-centered care as a team effort to provide individualized health care. Many participants believed that, to obtain high-quality care, patients had a responsibility to actively participate in their own care and work closely with providers. These participants reported accessing health information frequently, sharing decision making and feeling a sense of partnership with providers. Such attributes are particularly important for patient-centered care, and are aligned with patient competencies needed for implementation [28–29].

Participant-generated photography and interview data revealed various contextual factors influencing patient-centered care perceptions. Patient-provider communication and relationships were closely tied to overall perceptions of quality of care. This is corroborated by previous literature indicating that clear communication with providers and a sense of trust and respect is vital for patient satisfaction [14, 30–32]. Consistent with prior studies [3, 5], we found that environments of care, both physical and social, and accessibility of care were also important aspects of the patient experience.

We noted one area where participants developed a strategy to overcome an obstacle to accessing care. Participants highlighted a lack of knowledge among patients regarding their medical care and VA benefits. In response, many resolved to use word-of-mouth communication to disseminate information among other Veterans. Coupled with the importance of Veteran camaraderie among VA patients, this type of peer-level support and information sharing represents a valuable resource for health care organizations to harness in delivering better care.

Photovoice and the follow-up narrative methodology elicited in-depth and real-time practical findings that may be useful to leadership and health care providers. The value of these data can be realized in direct, actionable results that address patient needs and preferences. As discussed by patients in the evaluated sites, these may include improved accessibility within VA facilities, additional resources for transportation, more spaces that create a comforting atmosphere for patients, and enhanced dissemination of information regarding VA programs and services offered. These changes to the patient experience and environment of care surroundings can be replicated within VA facilities seeking to deliver patient-centered innovations that that resonate most among patients. Furthermore, these findings can be used in conjunction with additional quality improvement efforts to advance health care quality and patient-centered care.

Several limitations should be noted. Our findings, based on a relatively small sample size, may not be representative of the greater Veteran population. Additionally, patient perceptions were explored at a single point of time using a cross-sectional design; changes in perceptions over time were not examined. Limitations associated with photovoice may also have been introduced [19, 33]. Specifically, training instructions given at orientation may have influenced or biased participants’ photography. Further, data collection took place across two months, and participants were unable to comment on their own pictures for several weeks after taking them. Thus, some participants may have been unable to accurately recall or convey the intended meaning of their photographs during subsequent interviews.

Patients’ active involvement is needed at every stage of design and implementation to achieve patient-centered care [16, 29]. Further qualitative studies are needed that transcend traditional methods to engage patients in evaluation and improvement of patient-centered care delivery and quality. Such partnerships with patients capture the essence of patient-centered care and present an innovative strategy for health care organizations to advance care quality.

5.0 CONCLUSION

Photovoice deepened our understanding of VA patients’ perceptions of patient-centered care. We identified three categories of attributes that were relevant to the patient experience at the VA, (1) people, including communication with providers and staff, (2) places, including décor and signage, accessibility and transportation, and (3) system-level factors, including programs and services offered and informational resources. Photovoice was beneficial in engaging patients in a discussion around patient-centered care and building a foundation for improved patient-centered initiatives.

KEY POINTS FOR DECISION MAKERS.

Photovoice is an innovative tool to understand the patient perspective related to their care and engages patients in a qualitative evaluation of patient-centered care.

Findings highlight patient preferences and perceptions around patient-centered care, quality and environments of care.

Findings may be integrated into patient-centered innovations and care design strategies that embody what is most meaningful to patients.

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation and the Office of Research and Development Health Services Research and Development, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative.

Sherri LaVela and Salva Balbale contributed to the study concept, design and data collection. Megan Morris and Salva Balbale contributed to data analysis and interpretation. All authors, Sherri LaVela, Megan Morris, and Salva Balbale, contributed to the manuscript preparation and review. Salva Balbale will act as the overall guarantor of this manuscript.

Footnotes

None of the authors (Salva N. Balbale, Megan A. Morris and Sherri L. LaVela) have financial disclosures or any conflicts of interests.

The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.Epstein RM, Street RL. The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:100–103. doi: 10.1370/afm.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kellerman R, Kirk L. Principles of the patient-centered medical home. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:774–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lorig K. Patient-centered care depends on the point of view. Health Educ Behav. 2012;39:523–525. doi: 10.1177/1090198112455175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaller D. Commonwealth Fund. 2007. Patient-centered care: what does it take? [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiner SJ, Schwartz A, Sharma G, et al. Patient-centered decision making and health care outcomes: an observational study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:573–579. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-8-201304160-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;70:351–379. doi: 10.1177/1077558712465774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epstein RM, Fiscella K, Lesser CS, et al. Why the nation needs a policy push on patient- centered health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:1489–1495. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blaum C, Tremblay A, Forman J, et al. Improving chronic illness care for veterans within the framework of the patient-centered medical home: experiences from the Ann Arbor patient-aligned care team laboratory. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1:615–623. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0065-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hinojosa R, Hinojosa MS, Nelson K, et al. Veteran family reintegration, primary care needs, and the benefit of the patient-centered medical home model. The J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23:770–774. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2010.06.100094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meterko M, Wright S, Lin H, et al. Mortality among patients with acute myocardial infarction: the influences of patient–centered care and evidence–based medicine. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:1188–1204. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01138.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LaVela SL, Schectman G, Gering J, et al. Understanding health care communication preferences of Veteran primary care users. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LaVela SL, Gering J, Schectman G, et al. Optimizing primary care telephone access and patient satisfaction. Eval Health Prof. 2012;35:77–86. doi: 10.1177/0163278711411479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerteis M, Edgman-Levitan S, Daley J, et al. Through the patient's eyes: understanding and promoting patient-centered care. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bechtel C, Ness DL. If you build it, will they come? Designing truly patient-centered health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:914–920. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luxford K, Safran DG, Delbanco T. Promoting patient-centered care: a qualitative study of facilitators and barriers in healthcare organizations with a reputation for improving the patient experience. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011;23:510–515. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzr024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker TA, Wang CC. Photovoice: use of a participatory action research method to explore the chronic pain experience in older adults. Qual Health Res. 2006;16:1405–1413. doi: 10.1177/1049732306294118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Catalani C, Minkler M. Photovoice: A review of the literature in health and public health. Health Educ Behav. 2010;37:424–451. doi: 10.1177/1090198109342084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang C, Burris M. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:369–387. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang CC, Yi WK, Tao ZW, et al. Photovoice as a participatory health promotion strategy. Health Promot Int. 1998;13:75–86. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamasaki J. Picturing late life in focus. Health Communication. 2010;25:290–292. doi: 10.1080/10410231003698978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.True J, Fritch E. Understanding and addressing barriers to care for veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan: insights from a community-engaged research project. Poster presented at AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting; Baltimore, MD. 2013, June. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lorenz LS, Chilingerian JA. Using visual and narrative methods to achieve fair process in clinical care. J Vis Exp. 2011;16:2342–2348. doi: 10.3791/2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stokols D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. Am J Health Promot. 1996;10:282–298. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis K, Schoenbaum SC, Audet AM. A 2020 vision of patient–centered primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:953–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arora NK, McHorney CA. Patient preferences for medical decision making: who really wants to participate? Med Care. 2005;38:335–341. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200003000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Street RL, Jr, Gordon HS, Ward MM, et al. Patient participation in medical consultations: why some patients are more involved than others. Med Care. 2005;43:960–969. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000178172.40344.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernabeo E, Holmboe ES. Patients, providers, and systems need to acquire a specific set of competencies to achieve truly patient-centered care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:250–258. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hibbard JH. Engaging health care consumers to improve the quality of care. Med Care. 2003;41:I61–I70. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200301001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferguson LM, Ward H, Card S, et al. Putting the ‘patient’ back into patient-centered care: an education perspective. Nurse Educ Prac. 2013;13:283–287. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2013.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moreau A, Carol L, Dedianne MC, et al. What perceptions do patients have of decision making (DM)? Toward an integrative patient-centered care model. A qualitative study using focus-group interviews. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87:206–211. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zandbelt LC, Smets EM, Oort FJ, et al. Medical specialists' patient-centered communication and patient-reported outcomes. Med Care. 2007;45:330–339. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000250482.07970.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang C, Burris M. Empowerment through photo novella: portraits of participation. Health Educ Behav. 1994;21:171–186. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]