Abstract

Purpose.

The purpose of this project was to study the relationship between conjunctivochalasis (Cch) and ocular signs and symptoms of dry eye.

Methods.

Ninety-six patients with normal eyelid and corneal anatomy were prospectively recruited from a Veterans Administration hospital over 12 months. Symptoms (via the dry eye questionnaire 5 [DEQ5]) and signs of dry eye were assessed along with quality of life implications. Statistical analyses comparing the above metrics among the three groups included χ2, analysis of variance, and linear regression tests.

Results.

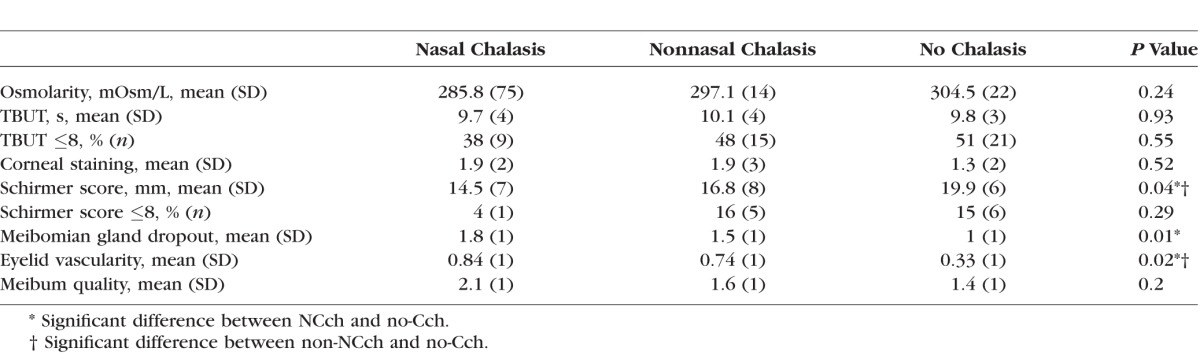

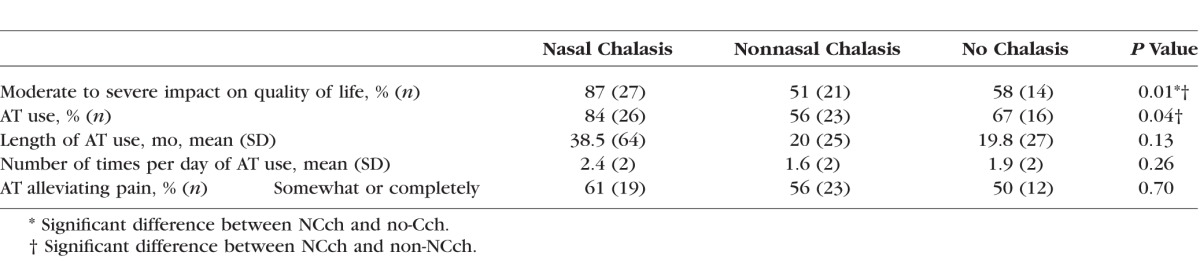

Participants were classified into three groups: nasal conjunctivochalasis (NCch; n = 31); nonnasal conjunctivochalasis (non-NCch; n = 41); and no conjunctivochalasis (no-Cch; n = 24). Patients with NCch had more dry eye symptoms than those with non-NCch (DEQ5: NCch = 13.8 ± 5.0, non-NCch = 10.2 ± 5.0, no-Cch = 11.6 ± 5.8; P = 0.014), and more ocular pain than those with Non-NCch and no-Cch (numerical rating scale [NRS]: NCch = 4.5 ± 3.0, non-NCch = 2.3 ± 2.8, no-Cch = 3.3 ± 2.6; P = 0.008). They also had worse dry eye signs compared to those with no-Cch measured by Schirmer score with anesthesia (NCch = 14.5 ± 6.9, non-NCch = 16.8 ± 8.2, no-Cch = 19.9 ± 6.4; P = 0.039); meibomian gland dropout (NCch 1.8 ± 0.9, non-NCch = 1.4 ± 1.0, no-Cch = 1.0 ± 1.0; P = 0.020); and eyelid vascularity (NCch = 0.84 ± 0.8, non-NCch = 0.74 ± 0.7, no-Cch = 0.33 ± 0.6; P = 0.019). Moreover, those with NCch more frequently reported that dry eye symptoms moderately to severely impacted their quality of life (NCch = 87%, non-NCch = 51%, no-Cch = 58%; P = 0.005).

Conclusions.

The presence of NCch associates with dry eye symptoms, abnormal tear parameters, and impacts quality of life compared with non-NCch and no-Cch. Based on these data, it is important for clinicians to look for Cch in patients with symptoms of dry eye.

Keywords: conjunctivochalasis, dry eye symptoms, dry eye signs

The epidemiology of conjunctivochalasis (Cch) has not been well studied in the United States; therefore, we aimed to analyze the association between Cch and dry eye. The presence of nasal Cch commonly associates with dry eye symptoms, abnormal tear parameters, and impacts quality of life.

Conjunctivochalasis (Cch) is described as lax and redundant folds of bulbar conjunctiva between the globe and eyelids. It can occur on the superior and/or inferior eyelid and can be localized to the nasal, middle, and/or temporal portion of the eyelid.1,2 These redundant folds of conjunctiva, specifically those located nasally, have been shown to disrupt tear flow by blocking the inferior nasal punctum.3 This may lead to decreased tear stability, pooling of tears in the eyelid cul-de-sac, and an increased concentration of inflammatory markers on the ocular surface.4,5

There is a debate on whether dry eye encompasses Cch or whether Cch represents a distinct clinical entity. Similar to dry eye, Cch has been found to be more frequent in older individuals6,7 and adversely affects vision-related quality of life.8 In fact, one study in a German population demonstrated that the presence of any Cch was associated with dry eye symptoms.9 Two other studies in Chinese and German populations examined Cch location and found that nasal conjunctivochalasis (NCch) was associated with higher dry eye symptoms compare with nonnasal conjunctivochalasis (non-NCch) and no conjunctivochalasis (no-Cch).8,10 With respect to signs, several studies in Chinese, Japanese, and German populations have demonstrated an association between NCch and bulbar conjunctival hyperemia,10 decreased tear film stability,8 and higher rose Bengal staining scores.5

Despite the abundance of data internationally, the epidemiology of Cch has not been as well studied in the United States. To build on current literature, we studied the epidemiology of Cch in our unique, ethnically mixed (e.g., Hispanic), predominantly male population. Specifically, we aimed to evaluate the relationship between Cch and traditionally assessed symptoms and signs of dry eye. In addition, we also measured novel parameters, including specific symptom complaints and responses to noninvasive treatment with artificial tears (AT).

Methods

Study Population

After approval by the institutional review board and with adherence to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, patients were prospectively recruited from the Miami Veterans Administration Ophthalmology Clinic between October 2013 and October 2014. After explanation of the nature and possible consequences of this study, informed consent was obtained from each patient. Patients underwent a complete ocular surface examination, and those with normal eyelid and corneal anatomy were included (n = 96). Exclusion criteria included contact lenses wear, ocular medications with the exception of artificial tears, active external ocular process, history of refractive or retinal surgery, history of glaucoma, and cataract surgery within the last 6 months. Additionally, patients with human immunodeficiency virus, sarcoidosis, graft-versus-host disease, collagen vascular disease, or other inflammatory conditions were excluded.

Data Collection

Demographic information for each patient was collected, including age, sex, race, ethnicity, and health status (determined by asking patients the following question “How would you describe your current health status”? Answer choices included excellent, good, fair, or poor). Given the positive relationship between cigarette smoking and wrinkles,11 we also evaluated the relationship between smoking status (assessed as current, previous, or never a smoker) and the presence of Cch. Dry eye symptoms were assessed via the Dry Eye Questionnaire Score 5 (DEQ5), which collects patient responses regarding tearing, dryness, and discomfort independent of visual function, and the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI), which includes visual function and questions related to difficulty with daily activities such as reading, using a computer, nighttime driving, and watching television.12,13 Patients were also asked about ocular pain severity (assessed with the numerical rating scale [NRS] scored 0–10), descriptors of eye pain (throbbing, sharpness, gnawing, hot-burning, aching, grittiness, itchiness, and irritation; all scored as present or absent), and other dry eye symptoms including sensitivity to heat, wind, light, and temperature (all scored 0–10). Moreover, the presence of individual symptoms (pain, visual complaints, and/or tearing) was recorded for each patient. This information was examined individually, as a comparison of frequencies of each symptom, and in combination, as a comparison of mean scores where each symptom received a score of 1 if present.

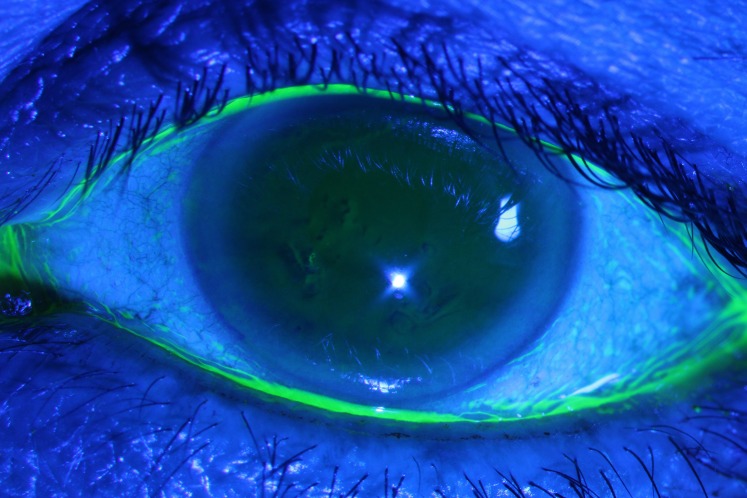

All patients were examined by the same optometrist (ALM). The presence and location of Cch was assessed via slit lamp examination. Fluorescein (5 μL) was pipetted onto the upper bulbar conjunctivae of each eye, and the patient was then instructed to blink softly. The presence of Cch was defined as an absent tear-lake with the replacement of the cul-de-sac with conjunctival tissue. The locations of these conjunctival folds (nasal, middle, or temporal) were recorded (Fig. 1). We defined no-Cch as the presence of tear lake without conjunctival folds. This schema was selected based on prior data that reported NCch to be most closely linked with dry eye symptoms.8,10

Figure 1.

Slit lamp photograph image demonstrating nasal and temporal conjunctivochalasis. There is an absent tear lake with the replacement of the cul-de-sac with conjunctival tissue in the nasal and temporal portions, while the middle portion of conjunctiva has an intact tear lake. Also demonstrated in this picture are central corneal irregularities, commonly seen in dry eye.

Further ocular surface examination, in order of performance, included:

Tear osmolarity (TearLAB, San Diego, CA, USA): measured once in each eye;

Tear breakup time (TBUT): three measurements taken in each eye and averaged;

Corneal staining (National Eye Institute [NEI] scale): five areas of cornea assessed (score 0–3 in each);

Schirmer strips with anesthesia; and

Meibomian gland assessment: drop out, measured via meibography, a technique that uses transillumination to evaluate degree of area loss of glands according to the Meiboscale (degree 0: ≈0%; degree 1: ≤25%, degree 2: 26%–50%; degree 3: 51%–75%; and degree 4: >75%).14

Eyelid vascularity was graded on a scale of 0 to 4 (0 = none; 1 = mild engorgement; 2 = moderate engorgement; 3 = severe engorgement)15 as was meibum quality (0 = clear consistency; 1 = cloudy consistency; 2 = granular consistency; 3 = toothpaste; 4 = no meibum expressed16 using digital pressure).

Additional recorded parameters included artificial tear use (hypromellose 0.4% with preservatives), impact of dry eye symptoms on quality of life (determined by asking patients the following question “How much do your dry eye symptoms affect your quality of life”? Answer choices included none, mild, or moderate to severe), and impact of artificial tear use on ocular pain (determined by asking patients the following question “Does use of artificial tears improve your ocular pain”? Answer choices included not at all or somewhat/completely). The number of patients that chose each of the above responses was totaled and compared in each category.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using a statistical package (SPSS Version 22; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Analyses included χ2 test for nominal variables and analysis of variance and Student's independent t-test for continuous variables. A linear regression analysis was performed to assess the contribution of the ocular surface findings including Cch to dry eye symptomatology. We considered a P-value less than 0.05 statistically significant for all analyses. Our sample size of 96 patients was deemed appropriate to detect differences between means given moderate effect size (f = 0.32) by one-way ANOVA17 with 80% power.

Results

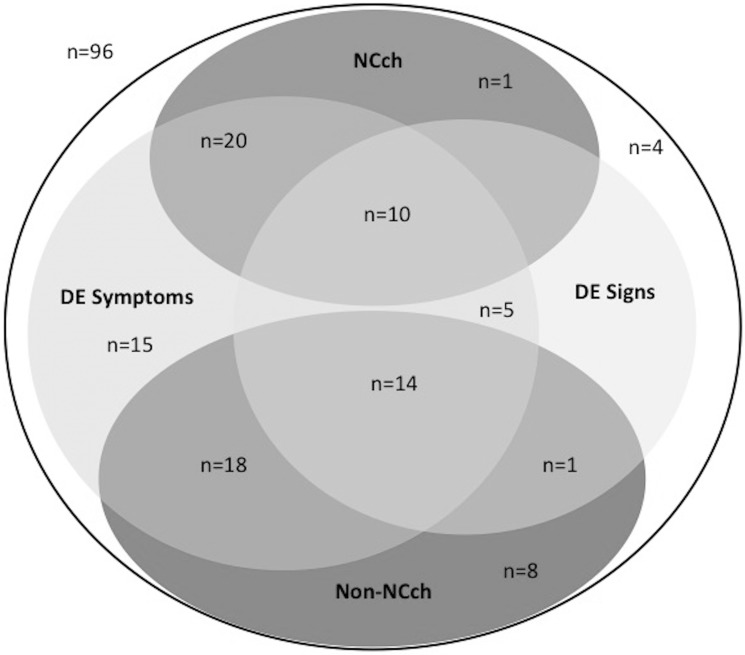

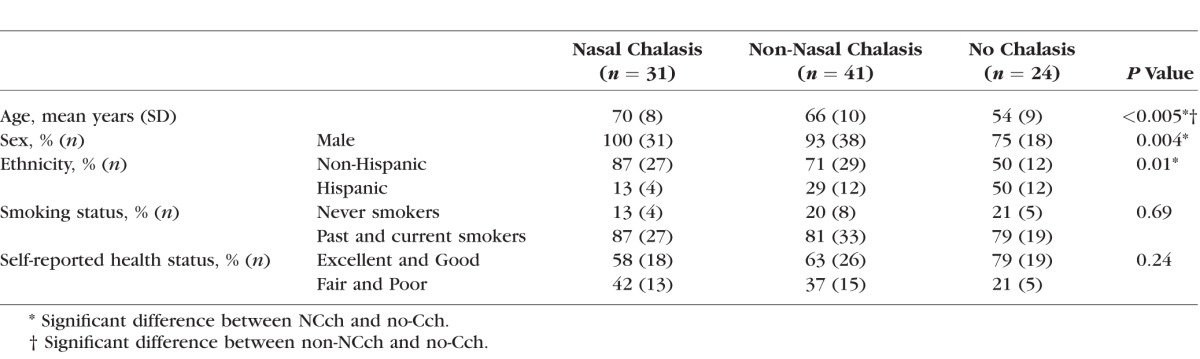

Participants were classified into 3 groups: NCch (n = 31), non-NCch (n = 41), and no-Cch (n = 24; Fig. 2). Greater proportions of patients with NCch were male and of non-Hispanic ethnicity compared with those with no-Cch (Table 1). Patients with NCch were also older than those with non-NCch and no-Cch.

Figure 2.

Venn diagram of study population; 96 total patients, 31 with NCch and 41 with non-NCch. Dry eye symptoms defined as dry eye questionnaire 5 score ≥6 and dry eye signs defined as corneal staining ≥3.

Table 1.

Demographics of the Study Population

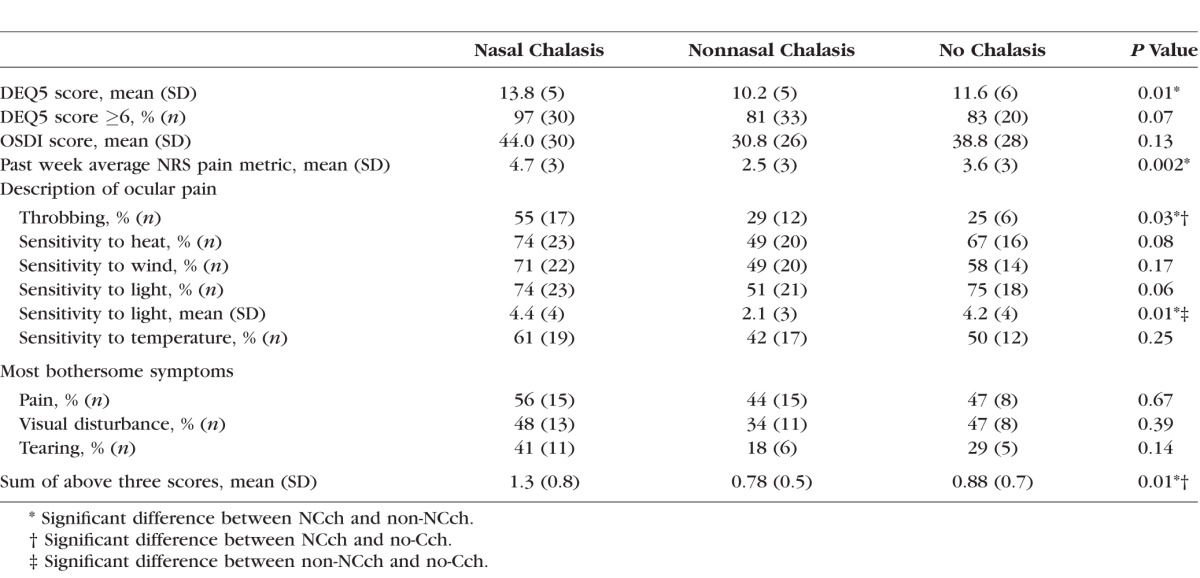

Looking at dry eye symptoms globally, patients with NCch reported higher DEQ5 scores compared with patients with non-NCch, but similar DEQ5 scores compared with patients with no-Cch (Table 2). Regarding dry eye complaints related to ocular pain, patients with NCch rated their ocular pain (averaged over the past week) as having a higher intensity than those with non-NCch. These patients also described their ocular discomfort as more throbbing compared with patients with non-NCch and no-Cch. All other descriptors of eye pain, including sharpness, gnawing, hot-burning, aching, grittiness, itchiness, and irritation were similar between the groups. Moreover, those with NCch reported increased sensitivity to light compared with those with non-NCch, but similar sensitivity to heat, wind, and temperature compared with those with non-NCch and no-Cch. Concerning other dry eye symptom metrics, a similar proportion of patients reported pain, blurry vision and/or tearing in each group. However, when summing these 3 symptoms (range, 0–3), patients with NCch had the highest sum of bothersome symptoms compared to patients with non-NCch and no-Cch.

Table 2.

Ocular Symptoms of the Study Population

With respect to ocular signs, patients with NCch had similar osmolarity, TBUT, corneal staining, and meibum quality compared to patients with non-NCch and no-Cch (Table 3). However, those with NCch had lower Schirmer scores, increased meibomian dropout, and increased eyelid vascularity compared to patients with no-Cch. Patients with non-NCch also had lower Schirmer scores and higher eyelid vascularity than patients with no-Cch.

Table 3.

Ocular Signs of the Study Population

Regarding quality of life, a higher frequency of patients in the NCch group reported that their dry eye symptoms moderately to severely impacted quality of life compared with patients with non-NCch and no-Cch. Patients with NCch also reported more frequent artificial tear use compared with patients with non-NCch. Interestingly, a similar proportion of those with NCch reported improvement (somewhat or completely) in ocular pain than those with non-NCch and no-Cch (Table 4).

Table 4.

Quality of Life and Artificial Tear Use in the Study Population

In a multivariable forward stepwise linear regression model considering demographics, Cch (NCch, non-NCch, no-Cch), dry eye signs, and artificial tear use, corneal staining was the variable most closely related to dry eye symptoms (DEQ5; B = −0.940, P = 0.041). In this model, Cch did not remain significantly associated with symptoms.

Discussion

This study analyzed the relationship between Cch and symptoms and signs of dry eye. We found that the presence of redundant conjunctival folds seen in patients with Cch correlated with some dry eye symptoms, with NCch associating with the most severe symptoms. Patients with NCch also had a more abnormal tear film seen by decreased Schirmer scores, increased meibomian gland dropout, and increased eyelid vascularity.

This paper is the first to assess the epidemiology of Cch and dry eye in a large American predominantly male population. Studies with Chinese and German populations demonstrated that patients with NCch had increased dry eye symptoms (measured with OSDI scores) compared with those with non-NCch and no-Cch.8,10 Similarly, we found patients with NCch had increased dry eye symptoms (measured with DEQ5) compared with those with non-NCch; however patients with NCch had similar DEQ5 scores compared with patients with no-Cch. Regarding specific dry eye symptoms, our study uniquely details symptoms experienced by patients with Cch. Those with NCch experienced more throbbing and sensitivity to light than those with non-NCch. These are clinical descriptors that ophthalmologist should be aware of when patients present with Cch.

Regarding ocular signs, similar to our study, a previous report of 45 eyes from Japan showed abnormal meibomian gland secretions and increased dropout in patients with NCch compared to those with no-Cch.5 While both our study and the literatures support an association between Cch and meibomian gland dysfunction,2,18 with increased age being a risk factor for both,19 it is not known whether or how meibomian gland dysfunction is causatively linked to Cch. Interestingly, the above study from Japan also showed an increase in inflammatory cytokines IL-1b, IL-6, and IL-10 in NCch compared with non-NCch and no-Cch, measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for tears.5 This suggests that inflammation may play a role in Cch, either in its original pathogenesis or in its subsequent effects on the ocular surface. From the above studies, we surmise that noted associations between NCch and unhealthy dry eye signs could be due to NCch blocking the inferior punctum, causing a cascade effect of altered distribution, composition, and stability of tears. As seen in our study, such secondary effects may include changes in basal tear secretion, meibomian gland health, and ocular surface health.

With respect to treatment, a large proportion of patients with NCch reported using artificial tears to treat symptoms and many responded. As such, it is a reasonable first-line therapy in these patients. Furthermore, given an association between Cch and inflammation, anti-inflammatory medications are also recommended and similarly have been shown to improve dry eye signs and symptoms in patients who suffer from dry eye syndrome.5,20–22 Finally, removal of redundant conjunctival folds, either with surgical or nonsurgical techniques (such as thermal cauterization or electrocoagulation) can improve symptoms and tear film stability.23–27

As with all studies, our findings must be considered along with the limitations of this study. First, our study was conducted at a Veterans Affairs hospital and therefore our population consists of predominantly older males. While the results of our study may not therefore extrapolate to women, men are an understudied population when it comes to dry eye; therefore, symptoms, signs, and anatomic disturbances in this population of patients are important to characterize. Second, we included many but not all clinical tests that assess the ocular surface; tests not included were a quantitative assessment of tear clearance, anterior segment ocular coherence tomography, and rose Bengal staining. Furthermore, we defined Cch as the presence or absence of a tear lake in each segment, as we believe this is a fast and practical way for clinicians to study Cch. However, we did not further grade the severity of Cch in each quadrant. As such, these specific tests and methodologies may have given us different information on the interaction between Cch and the ocular surface. Third, our study was cross-sectional in design and therefore the duration and stability of Cch in our population is unknown as is its temporal relationship to the symptoms and signs of dry eye.

Despite these limitations, this study provides clinicians with a broad description of the signs and symptoms associated with Cch, with emphasis on the importance of the location of Cch. The importance lies in the fact that this disease affects not only ocular health, but patients affected also reported an increased negative impact on quality of life. Based on this data, it is important for clinicians to look for conjunctivochalasis in patients with dry eye.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Clinical Sciences Research and Development's Career Development Award CDA-2-024-10S (AG); NIH Center Core Grant P30EY014801; and Research to Prevent Blindness Unrestricted Grant, Department of Defense (DOD; Grant No. W81XWH-09-1-0675 and Grant No. W81XWH-13-1-0048 ONOVA; institutional).

Disclosure: P. Chhadva, None; A. Alexander, None; A.L. McClellan, None; K.T. McManus, None; B. Seiden, None; A. Galor, None

References

- 1.Hughes WL.Conjunctivochalasis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1942; 25: 48–51. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meller D, Tseng SC.Conjunctivochalasis: literature review and possible pathophysiology. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998; 43;225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosniak SL, Smith BC.Conjunctivochalasis. Adv Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984; 3: 153–155.4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu D.Conjunctivochalasis. A cause of tearing and its management. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986; 2: 25–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Dogru M,, Matsumoto Y, et al. The impact of nasal conjunctivochalasis on tear functions and ocular surface findings. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007; 144: 930–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gumus K,, Pflugfelder SC.Increasing prevalence and severity of conjunctivochalasis with aging detected by anterior segment optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013; 155: 238–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X, Li Q,, Zou H, et al. Assessing the severity of conjunctivochalasis in a senile population: a community-based epidemiology study in Shanghai, China. BMC Public Health. 2011; 11: 198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le Q,, Cui X, Xiang J,, et al. Impact of conjunctivochalasis on visual quality of life: a community population survey. PLoS One. 2014; 9: e110821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoh H, Schirra F,, Kienecker C, et al. Lid-parallel conjunctival folds are a sure diagnostic sign of dry eye. Ophthalmology. 1995; 92: 802–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pult H,, Purslow C, Murphy PJ.The relationship between clinical signs and dry eye symptoms. Eye (Lond). 2011; 25: 502–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ernster VL, Grady D,, Miike R, et al. Facial wrinkling in men and women, by smoking status. Am J Public Health. 1995; 85: 78–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Begley CG, Caffery B Chalmers RL, Mitchell GL; . Dry Eye Investigation (DREI) Study Group. Use of the dry eye questionnaire to measure symptoms of ocular irritation in patients with aqueous tear deficient dry eye. Cornea. 2002; 21: 664–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schiffman RM, Christianson MD,, Jacobsen G, et al. Reliability and Validity of the Ocular Surface Disease Index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000; 118: 615–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pult H.Meiboscale. Dr Heiko Pult - Optometry & Vision Research. Available at: http://www.heiko-pult.de/media/9b33036c74e3ec71ffff8016fffffff2.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2015.

- 15.Foulks GN, Bron AJ.Meibomian gland dysfunction: a clinical scheme for description, diagnosis, classification, and grading. Ocul Surf. 2003; 1: 107–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomlinson A, Bron AJ,, Korb DR, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the clinical trials subcommittee. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 2006–2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen J.Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates;1988. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Pascuale MA, Espana EM,, Kawakita T, et al. Clinical characteristics of conjunctivochalasis with or without aqueous tear deficiency. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004; 88: 388–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uchino M,, Dogru M, Yagi Y,, et al. The features of dry eye disease in a Japanese elderly population. Optom Vis Sci. 2006; 83: 797–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erdogan-Poyraz C, Mocan MC,, Bozkurt B, et al. Elevated tear interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 levels in patients with conjunctivochalasis. Cornea. 2009; 28: 189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Acera A,, Suarez T, Rodriguez-Agirretxe I,, et al. Changes in tear protein profile in patients with conjunctivochalasis. Cornea. 2011; 30: 42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson SE, Perry HD.Long-term resolution of chronic dry eye symptoms and signs after topical cyclosporine treatment. Ophthalmology. 2007; 114: 76–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hara S, Kojima T,, Ishida R, et al. Evaluation of tear stability after surgery for conjunctivochalasis. Optom Vis Sci. 2011; 88: 1112–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kashima T,, Akiyama H, Miura F,, et al. Improved subjective symptoms of conjunctivochalasis using bipolar diathermy method for conjunctival shrinkage. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011; 5: 1391–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang XR, Zhang ZY,, Hoffman MR.Electrocoagulative surgical procedure for treatment of conjunctivochalasis. Int J Surg. 2012; 97: 90–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otaka I, Kyu NA.New surgical technique for management of conjunctivochalasis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000; 129: 385–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meller D, Maskin SL,, Pires RT,, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation for symptomatic conjunctivochalasis refractory to medical treatments. Cornea. 2000; 19: 796–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]