Summary

Background

Supplementation of vitamin A in children aged 6–59 months improves child survival and is implemented as global policy. Studies of the efficacy of supplementation of infants in the neonatal period have inconsistent results. We aimed to assess the efficacy of oral supplementation with vitamin A given to infants in the first 3 days of life to reduce mortality between supplementation and 180 days (6 months).

Methods

We did an individually randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of infants born in the Morogoro and Dar es Salaam regions of Tanzania. Women were identified during antenatal clinic visits or in the labour wards of public health facilities in Dar es Salaam. In Kilombero, Ulanga, and Kilosa districts, women were seen at home as part of the health and demographic surveillance system. Newborn infants were eligible for randomisation if they were able to feed orally and if the family intended to stay in the study area for at least 6 months. We randomly assigned infants to receive one dose of 50 000 IU of vitamin A or placebo in the first 3 days after birth. Infants were randomly assigned in blocks of 20, and investigators, participants’ families, and data analysis teams were masked to treatment assignment. We assessed infants on day 1 and day 3 after dosing, as well as at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after birth. The primary endpoint was mortality at 6 months, assessed by field interviews. The primary analysis included only children who were not lost to follow-up. This trial is registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR), number ACTRN12610000636055.

Findings

Between Aug 26, 2010, and March 3, 2013, 31 999 newborn babies were randomly assigned to receive vitamin A (n=15 995) or placebo (n=16 004; 15 428 and 15 464 included in analysis of mortality at 6 months, respectively). We did not find any evidence for a beneficial effect of vitamin A supplementation on mortality in infants at 6 months (26 deaths per 1000 livebirths in vitamin A vs 24 deaths per 1000 livebirths in placebo group; risk ratio 1·10, 95% CI 0·95–1·26; p=0·193). There was no evidence of a differential effect for vitamin A supplementation on mortality by sex; risk ratio for mortality at 6 months for boys was 1·08 (0·90–1·29) and for girls was 1·12 (0·91–1·39). There was also no evidence of adverse effects of supplementation within 3 days of dosing.

Interpretation

Neonatal vitamin A supplementation did not result in any immediate adverse events, but had no beneficial effect on survival in infants in Tanzania. These results strengthen the evidence against a global policy recommendation for neonatal vitamin A supplementation.

Introduction

Every year, an estimated 6·9 million children die before their fifth birthday. About 44% of deaths of children younger than 5 years occur in the neonatal period, mostly in southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.1 The Millennium Development Goal for child survival will not be achieved without additional investments to address newborn baby deaths. Interest to estimate trends and causes of newborn deaths2 and to reduce mortality with safe and efficacious interventions3 has increased. Vitamin A deficiency is thought to be a major public health issue in low-income countries.4,5 Evidence from a systematic review6 and meta-analyses7,8 of randomised controlled trials indicate a significant benefit of periodic vitamin A supplementation for children aged 6–59 months, reducing all-cause mortality by 23–30%. This body of evidence prompted policy recommendations by WHO9 and catalysed the implementation of large-scale supplementation programmes for children younger than 5 years to improve child survival.9

Results from studies to establish whether vitamin A supplementation can provide similar benefits in children younger than 6 months have conflicting results, ranging from no benefit10 to potential benefit11–13 or possible harm, at least in subsets of children.14,15 This conflicting evidence prompted the development of large trials to generate the necessary evidence to inform global programmes that aim to improve child survival.16

We did a trial in Tanzania to establish the effect on infant mortality of vitamin A supplementation given on the day of birth or within the next 2 days. This is one of three large trials recommended by a technical consultation team convened by WHO in December, 2008, to inform global policy for or against newborn vitamin A supplementation. Two companion studies done in India and Ghana are reported elsewhere.17,18

Methods

Study design and participants

We did a randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in Dar es Salaam and Morogoro regions of Tanzania. The characteristics of the study areas have been described elsewhere.16 In Dar es Salaam, we enrolled mothers and newborn babies from ten large antenatal clinics and labour wards in the catchment areas, and in the Morogoro region, the study was nested within the Ifakara Health Institute’s health and demographic surveillance system (HDSS). The Ifakara HDSS covers about 2400 km2 and is operational in 12 villages in Ulanga and 46 in Kilombero. For the purpose of this study, we extended the surveillance area to include 13 additional villages from an adjacent district of Kilosa. Ifakara HDSS is a member of the INDEPTH Network.19

In Dar es Salaam, we identified pregnant women either during regular antenatal visits or in the labour wards of public health facilities that had delivery services. In Kilombero, Ulanga, and Kilosa districts, pregnant women were seen at home during regular household visits as part of the HDSS rounds and in labour wards. All births that occurred as part of the HDSS or at designated labour wards were eligible for screening. Newborn babies of women who were part of HDSS were reported to dosing supervisors through self-reports, by field interviewers or village-based key informants. Key informants were remunerated for reporting births with a tiered incentive package that encouraged early reporting of births. At least one parent of every livebirth was asked for consent to participate in the study. Those who gave written informed consent were screened to establish whether the infant met the eligibility criteria. Newborn babies were eligible for randomisation if they were able to feed orally, if the family intended to stay in the study area for at least 6 months, and if parents provided written informed consent to participate. Babies who were enrolled in other trials were excluded.

We sought written individual consent to follow women’s pregnancy until delivery. For women who are unable to read and write, a witness was invited to observe and a health worker read the consent and asked the mother to thumb seal upon agreement. Information about household demographics, nutritional status, and pregnancy complications was collected from all mothers. An international data and safety monitoring board reviewed data quarterly and convened twice during the course of the study to complete interim analyses to decide whether to continue the trial on the basis of stopping rules decided a priori.20 The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Harvard School of Public Health, Ifakara Health Institute, Medical Research Coordinating Council of Tanzania, and by the WHO Ethical Review Committee.

Randomisation and masking

We randomly assigned infants to receive either vitamin A or a placebo. The unit of randomisation was the individual infant. Block randomisation was done at WHO (Geneva, Switzerland) in block sizes of 20 (ten infants received vitamin A and ten received placebo). Codes for the experimental regimens were kept with the data and safety monitoring board and broken during the analysis after a cleaned and locked database for the study was submitted to WHO.

Strides Arcolab (Bangalore, India) supplied the capsules for this study and the companion studies in India and Ghana. Each dose contained 50 000 IU of vitamin A (retinol palmitate and minute amounts of vitamin E [9·5–12·6 IU] in soybean oil) or placebo (minute amounts of vitamin E [9·5–12·6 IU] in soybean oil). The vitamin A and placebo capsules were identical in taste and appearance. Capsules were individually packed in blister packs of two capsules each; one for the dose and the second for the backup dose. Labels for the capsules were printed at WHO with country and infant study number in sequential order. Labels were first fixed on blister packs containing vitamin A capsules. The capsules were then packed in sealed boxes and removed from the packing room before the next treatment group was brought in. Investigators had no access to the randomisation list or to any information that would allow them to deduce the allocation. Participants’ families, and trial personnel (including those distributing capsules and collecting, processing, and analysing data) were masked to treatment assignment for the duration of the trial.

Procedures

Nurses or dosing supervisors gave the infants vitamin A or placebo as a single-dose oral capsule either at the babies’ home or in labour wards at least 2 h after birth or within the next 2 days. Study regimen was stored in cool and dry rooms that had temperatures between 15°C and 30°C. Temperatures were measured with a thermometer and recorded daily in a log book by a pharmacist and study personnel who were not part of the trial. They also provided the study coordinators with the capsules that were next in sequence for dosing each time the dosing teams needed replenishment. The study coordinators in turn gave each study nurse and field interviewer packs to give to the next ten eligible infants before receiving another one. The backup dose was given only when there was accidental spillage by the person giving the supplement. Enrolled newborn babies were issued child health cards with the number written on the blister pack containing the dose. Infant’s birthweight was assessed at the facility or home, by study staff at the time of dosing. A wealth index was generated from household ownership of durable assets.21

Trained field interviewers visited enrolled infants at home (or in health facilities for cases in which the mother and child were not discharged after delivery) 1 day and 3 days after dosing to monitor possible adverse events after supplementation. If infants developed any unexpected clinical signs or behaviour changes after supplementation, then study staff advised mothers or caregivers of newborn babies to take their babies to the nearest health facility. Standard care of according to Tanzania Ministry of Health was provided for such cases.

Field interviewers did home visits at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after birth for all enrolled infants to find out vital status and to obtain information about any morbidity that resulted in hospital admission, feeding in the past 24 h, and immunisation records. Medical reports or mothers’ accounts were collected for hospital admission, date of admission, length of hospital stay, and reason for admission. To minimise loss to follow-up, caregivers and children who were absent at the time of visit were called by phone to reschedule an appointment or the home was revisited twice monthly until the visit was completed. In addition to the field interviewers, a network of key informants within HDSS was used to find out vital status and report to the study team. All reported deaths of children were investigated and trained field staff visited the family at least 6 weeks after the date of death to do a verbal autopsy interview.

The three studies17,18 used standard questionnaires with a defined set of core variables. Each core variable had a standard definition, acceptable range limits, and an agreed data format. Research staff were carefully trained to carry out surveillance, interview families, obtain informed consent, administer the study regimen, weigh infants, and collect follow-up information. Data were captured electronically using tablet computers and netbooks and were uploaded to a main server through a cell network or wireless internet. Detailed range and consistency checks were encoded within the electronic data entry platform to ensure data quality. Data were further reviewed by the data management team and queries were resolved by site supervisors or field coordinators. Clean data were uploaded each month to WHO. Site supervisors and field managers called and visited a random sample of mothers each week to confirm the accuracy and quality of data collection completed by field interviewers. Additionally, field interviewers received supervised visits on a rotating basis.

We tested blood specimens for serum retinol and retinol-binding protein in subsamples of infants in vitamin A and placebo treatment groups at age 2 weeks and 3 months to examine the effect of supplementation on mean serum retinol, and in a subsample of mothers at 3 months to ascertain maternal vitamin A status in this population. Written informed consent was sought from the mother before a nurse, physician, or lab technician took 0·5–1·0 mL of heel-prick blood from the infant and venous blood from consenting mothers. To account for spatial and seasonal variation, we randomly sampled across all study areas and seasons.

Blood samples (0·5–1·0 mL for infants and 2·0–5·0 mL for mothers) were collected in vacutainers and were sent to the laboratory for serum separation. Serum aliquots were kept in cryotubes and stored at −80°C in freezers. Blood samples were analysed at Boston Children’s Hospital (MA, USA) for serum retinol, retinol-binding protein, and C-reactive protein concentrations. Vitamin A (retinol) concentrations were measured with high-performance liquid chromatography using a Shimadzu system from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Retinol-binding protein 4 concentrations were measured with an ELISA assay from R&D Systems. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein concentrations were measured with an immunoturbidimetric assay on the Roche P Modular system (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was death between supplementation and 180 days of age (6 months). Secondary outcomes were defined as death between supplementation and 28 days of age, death between supplementation and 365 days of age, and hospital admission in the first 6 months of life, which was defined as admission to hospital as an inpatient as reported by the mother. In the case of more than one hospital admissions, each infant contributed only their first admission to the analysis. Adverse events were defined as any harmful or undesired effect reported by the family within 3 days of supplementation. These included death, presence of bulging fontanelle confirmed by research team through physical examination of the infant, vomiting, fever, diarrhoea, inability to suck or feed, and convulsions.

Statistical analysis

We planned to enrol 32 000 newborn babies to detect a 15% reduction in mortality from enrolment to age 6 months, with 85% power and 5% significance level, assuming infant mortality of 60 per 1000 livebirths and a 10% loss to follow-up. This sample size was also adequate to detect possible effect sizes of 15% in post-enrolment infant mortality and 20% in post-enrolment neonatal mortality (secondary outcome).

Four protocol violations were documented. In two instances, two infants were dosed twice with different capsules. For these infants, we analysed data based on the first capsule given. In two other instances, the infants received the backup doses of other infants who had already been dosed. In these two cases, the infants were analysed according to the dose that they received.

We included only children who were not lost to follow up for the primary analyses, which were done with SAS version 9.2 using a prespecified plan of analysis.16,22 The intention-to-treat analysis is included in the appendix. We used both person-time (infant-years of follow-up) and livebirths as the denominator for the primary and secondary outcomes on mortality. We used risk ratios, risk differences, and their corresponding 95% CIs to estimate the effect of vitamin A. We also presented χ2 or Fisher’s exact test p values (in cases where there were fewer than five observations in a cell). We tested for interactions between intervention and sex for both primary and secondary outcomes and presented p values from the likelihood ratio test comparing the model with and without the interaction term. We also did analyses of all predefined subgroups by sex, birthweight, wealth status, diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus immunisation and maternal vitamin A supplementation.

We compared mean serum retinol and retinol-binding protein in infants given each regimen using Student t test and using multiple linear regression adjusting for C-reactive protein concentrations. We examined the effect of the supplements on vitamin A status by comparing proportions for different cutoffs of vitamin A deficiency severity, defined as mild (<1·05 μmol/L), moderate (<0·7 μmol/L), or severe (<0·35 μmol/L).

The study was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR), number ACTRN12610000636055.

Role of funding source

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation funded the study, with funds supplied to the World Health Organization. The funder did not have any role in the design of the study, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of this report. The corresponding author had full access to the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

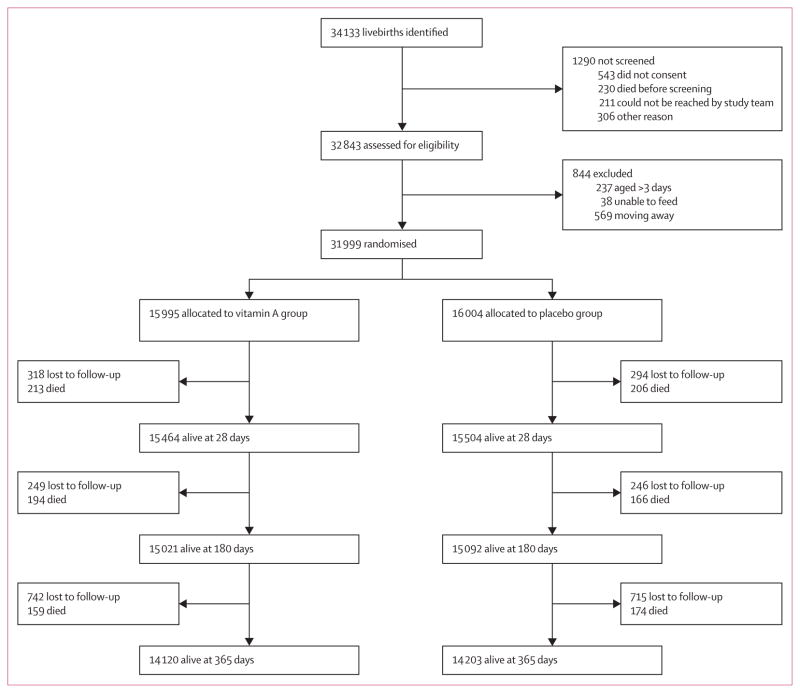

Between Aug 26, 2010, and March 3, 2013, we identified and assessed 34 133 livebirths for eligibility (figure 1). 1290 were not screened because they did not consent, died before screening, or could not be contacted. 844 (3%) newborn infants were excluded (figure 1). We randomly assigned 31 999 newborn babies to receive either vitamin A (n=15 995) or placebo (n=16 004). Most (24 888; 78%) infants received vitamin A or placebo within 24 h (table 1). Maternal and infant characteristics were similar in both groups (table 1). Three-quarters of women received a large dose of vitamin A supplementation within 24 h of birth as part of standard of care.

Figure 1.

Trial profile

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Vitamin A group (n=15 995) | Placebo group (n=16 004) | |

|---|---|---|

|

Infant characteristics

| ||

| Boys* | 8443 (52·8%) | 8340 (52·1%) |

| Age at dosing | ||

| <12 h | 7552 (47·2%) | 7663 (47·9%) |

| 12–23 h | 4847 (30·3%) | 4826 (30·2%) |

| 24–47 h | 2876 (18%) | 2791 (17·4%) |

| ≥48 h | 282 (1·8%) | 299 (1·9%) |

| Mean (h) | 15·5 (12) | 15·4 (12) |

| Birthweight | ||

| Mean (kg) | 3·02 (1) | 3·02 (1) |

| Less than 2·5 kg | 1908 (11·9%) | 1974 (12·3%) |

| Twin or triplet | 539 (3·4%) | 569 (3·6%) |

| Breastfed before supplementation* | 15 750 (98·5%) | 15 740 (98·4%) |

| Mean age at breastfeeding initiation (h) | 1·08 (4) | 0·99 (4) |

| Vaccination with first DPT vaccine* | ||

| Yes | 14 281 (89·3%) | 14 345 (89·6%) |

| No | 771 (4·8%) | 773 (4·8%) |

| Mean age at vaccination (days) | 43·7 (20) | 43·8 (19) |

| Number of living children* | ||

| One | 3337 (20·9%) | 3284 (20·5%) |

| Two | 4469 (27·9%) | 4629 (28·9%) |

| Three or more | 7749 (48·4%) | 7638 (47·7%) |

| Number of children who have died* | ||

| First birth | 2912 (18·2%) | 2832 (17·7%) |

| None | 9820 (61·4%) | 9834 (61·4%) |

| One | 1009 (6·3%) | 1075 (6·7%) |

| Two or more | 814 (5·1%) | 844 (5·3%) |

| Born in health facility | 13 921 (87%) | 13 902 (86·9%) |

|

| ||

|

Maternal characteristics

| ||

| Maternal age* | ||

| <20 years | 2274 (14·2%) | 2209 (13·8%) |

| 20–24 years | 4650 (29·1%) | 4652 (29·1%) |

| 25–29 years | 4377 (27·4%) | 4405 (27·5%) |

| ≥30 years | 4235 (26·5%) | 4300 (26·9%) |

| Highest educational level* | ||

| None | 1335 (8·3%) | 1310 (8·2%) |

| Primary | 11 988 (74·9%) | 12 066 (75·4%) |

| Secondary | 1026 (6·4%) | 1018 (6·4%) |

| More than secondary | 465 (2·9%) | 454 (2·8%) |

| Wealth quintile of household* | ||

| First (lowest) | 2894 (18·1%) | 2943 (18%) |

| Second | 2978 (18·6%) | 2879 (18%) |

| Third | 2863 (17·9%) | 2863 (18%) |

| Fourth | 2949 (18·4%) | 2996 (19%) |

| Fifth (highest) | 3290 (20·6%) | 3308 (21%) |

| Received mega-dose of vitamin A* | ||

| Yes | 12 130 (75·8%) | 12 101 (75·6%) |

| No | 3655 (22·9%) | 3677 (23·0%) |

Data are n (%) or mean (SD). DPT=diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus.

The numbers do not add up to 100% because of missing data.

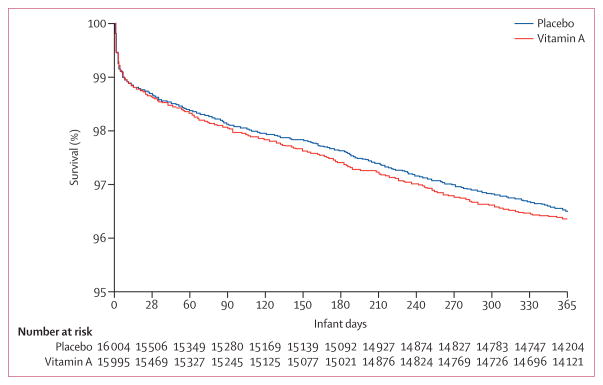

Assessment for infant mortality at age 6 months was based on 15 428 infants allocated to vitamin A and 15 464 allocated to placebo (table 2). We recorded 407 infant deaths and a mortality rate of 26·38 per 1000 livebirths in the vitamin A group and 372 infant deaths and a mortality rate of 24·06 per 1000 livebirths in the placebo group at 6 months. The relative risk was 1·10 (95% CI 0·95–1·26; p=0·193), and risk difference was 2·32 (95% CI −1·17 to 5·82), indicating no effect of supplementation on overall mortality at 6 months. Relative risk for mortality at 28 days was 1·04 (95% CI 0·86–1·25; p=0·714). Similarly, mortality at 12 months (n=29 435) of age was not different between the vitamin A and placebo groups; relative risk 1·04 (95% CI 0·93–1·17; p=0·494). The relative risk for admission at 6 months was 1·10 (95% CI 0·94–1·28; p=0·233). The effects of vitamin A supplementation on primary and secondary endpoints did not differ by sex: interaction with mortality at age 28 days (p=0·594), 6 months (p=0·760), and 12 months (p=0·111), and hospital admission at 6 months of age (p=0·422; table 2; figure 2).

Table 2.

Effect of vitamin A on endpoints

| Vitamin A group | Placebo group | Risk per 1000 in vitamin A group | Risk per 1000 in placebo group | Risk difference per 1000 (95% CI) | Risk ratio (95% CI) | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Events | Newborns | Events | Newborns | ||||||

|

Mortality at 6 months (n=30 892)

| |||||||||

| Overall | 407 | 15 428 | 372 | 15 464 | 26·38 | 24·06 | 2·32 (−1·17 to 5·82) | 1·10 (0·95 to 1·26) | 0·193 |

| Boys | 233 | 8135 | 215 | 8070 | 28·64 | 26·64 | 2·00 (−3·05 to 7·05) | 1·08 (0·90 to 1·29) | 0·438 |

| Girls | 174 | 7291 | 157 | 7392 | 23·87 | 21·24 | 2·63 (−2·18 to 7·43) | 1·12 (0·91 to 1·39) | 0·284 |

| Interaction with sex | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | 0·760 |

|

| |||||||||

|

Neonatal mortality (n=31 387)

| |||||||||

| Overall | 213 | 15 677 | 206 | 15 710 | 13·59 | 13·11 | 0·47 (−2·07 to 3·01) | 1·04 (0·86 to 1·25) | 0·714 |

| Boys | 124 | 8273 | 124 | 8198 | 14·99 | 15·13 | −0·14 (−3·86 to 3·58) | 0·99 (0·77 to 1·27) | 0·942 |

| Girls | 89 | 7402 | 82 | 7510 | 12·02 | 10·92 | 1·11 (−2·31 to 4·52) | 1·10 (0·82 to 1·48) | 0·526 |

| Interaction with sex | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | 0·594 |

|

| |||||||||

|

Mortality at 12 months (n=29 435)

| |||||||||

| Overall | 566 | 14 686 | 546 | 14 749 | 39 | 37 | 1·52 (−2·84 to 5·88) | 1·04 (0·93 to 1·17) | 0·494 |

| Boys | 312 | 7745 | 324 | 7713 | 40 | 42 | −1·72 (−7·99 to 4·54) | 0·96 (0·82 to 1·12) | 0·590 |

| Girls | 254 | 6939 | 222 | 7034 | 37 | 32 | 5·04 (−0·97 to 11·06) | 1·16 (0·97 to 1·38) | 0·100 |

| Interaction with sex | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | 0·111 |

|

| |||||||||

|

Hospital admission up to 6 months (n=30 895)

| |||||||||

| Overall | 332 | 15 429 | 303 | 15 466 | 21·52 | 19·59 | 1·93 (−1·24 to 5·09) | 1·10 (0·94 to 1·28) | 0·233 |

| Boys | 194 | 8135 | 166 | 8072 | 23·85 | 20·56 | 3·28 (−1·25 to 7·82) | 1·16 (0·94 to 1·42) | 0·156 |

| Girls | 138 | 7292 | 137 | 7392 | 18·92 | 18·53 | 0·39 (−3·99 to 4·78) | 1·02 (0·81 to 1·29) | 0·861 |

| Interaction with sex | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | 0·422 |

All event rates given over participants not lost to follow-up before end of risk period.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve up to 12 months

In both vitamin A and placebo groups, more than half of infants at 2 weeks and at 3 months had moderately low vitamin A concentrations (<0·7 μmol/L). At 2 weeks, mean serum retinol concentrations, mean serum retinol-binding protein concentrations, or the proportion of infants with serum retinol concentrations lower than 0·7 μmol/L did not differ between the two groups. However, at age 3 months, infants in the vitamin A group had a significantly higher mean serum retinol concentration than did the placebo group (mean difference between the groups 0·043 [95% CI 0·003–0·083]). Similarly, infants in the vitamin A group were, on average, less likely to have moderate serum retinol concentrations compared with the placebo group at 3 months (relative risk −0·107; 95% CI −0·191 to 0·022). When we compared mothers of infants assigned to each group 3 months after birth, there were no significant differences in mean serum retinol concentrations, mean serum retinol-binding protein concentrations, or proportions of infants with vitamin A deficiency between groups (table 3). Adjustment by C-reactive protein did not substantially change serum retinol or retinol-binding protein concentration results (data not shown).

Table 3.

Serum retinol and retinol-binding protein concentrations in infants and mothers after supplementation

| Vitamin A | Placebo | Mean difference or risk difference (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Infants at age 2 weeks

| ||||

| Number tested | 277 | 284 | ·· | ·· |

| Infants with serum retinol results | 255 (92%) | 265 (93%) | ·· | ·· |

| Mean serum retinol (μmol/L) | 0·69 (0·20) | 0·69 (0·22) | 0 (0–40·03) | 0·930 |

| Serum retinol <1·05 μmol/L | 240 (94%) | 249 (94%) | 0·16 (−3·91 to 4·23) | 0·940 |

| Serum retinol <0·70 μmol/L | 144 (57%) | 142 (54%) | 2·89 (−5·66 to 11·43) | 0·508 |

| Serum retinol <0·35 μmol/L | 4 (2%) | 8 (3%) | −1·45 (−4·01 to 1·11) | 0·383* |

| Infants with serum retinol-binding protein results | 277 (100%) | 284 (100%) | ·· | ·· |

| Mean serum retinol-binding protein in μmol/L | 0·79 (0·20) | 0·80 (0·23) | −0·01 (−0·05 to 0·02) | 0·429 |

| Retinol-binding protein <0·70 μmol/L | 98 (35%) | 91 (32%) | 3·34(−4·48 to 11·16) | 0·403 |

| Retinol-binding protein <0·35 μmol/L | 1 (<1%) | 3 (1%) | −0·70(−2·08 to 0·69) | 0·624* |

|

| ||||

|

Infants at age 3 months

| ||||

| Number tested | 280 | 266 | ·· | ·· |

| Infants with serum retinol results | 271 (97%) | 255 (96%) | ·· | ·· |

| Mean serum retinol (μmol/L) | 0·72 (0·23) | 0·68 (0·24) | 0·04 (0–0·08) | 0·035 |

| Serum retinol <1·05 μmol/L | 250 (92%) | 238 (93%) | −1·08 (−5·50 to 3·33) | 0·632 |

| Serum retinol <0·70 μmol/L | 138 (51%) | 157 (62%) | −10·65 (−19·08 to 2·22) | 0·014 |

| Serum retinol <0·35 μmol/L | 8 (3%) | 7 (3%) | 0·21 (−2·64 to 3·05) | 0·887 |

| Infants with serum retinol-binding protein results | 280 (100%) | 266 (100%) | ·· | ·· |

| Mean serum retinol-binding protein (μmol/L) | 0·77 (0·20) | 0·74 (0·24) | 0·03 (0–0·07) | 0·075 |

| Retinol-binding protein <0·70 μmol/L | 115 (41%) | 133 (50%) | −8·93 (−17·25 to 0·6) | 0·036 |

| Retinol-binding protein <0·35 μmol/L | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | −0·04 (−1·47 to 1·39) | 1·000* |

|

| ||||

|

Mothers

| ||||

| Number tested | 262 | 253 | ·· | ·· |

| Mothers with serum retinol results | 262 (100%) | 253 (100%) | ·· | ·· |

| Mean serum retinol (μmol/L) | 1·25 (0·42) | 1·22 (0·39) | 0·03 (−0·04 to 0·10) | 0·418 |

| Serum retinol <1·05 μmol/L | 82 (31%) | 90 (36%) | −4·28 (−12·42 to 3·87) | 0·304 |

| Serum retinol <0·70 μmol/L | 13 (5%) | 21 (8%) | −3·34 (−7·64 to 0·96) | 0·127 |

| Serum retinol <0·35 μmol/L | 0 | 2 (1%) | −0·79 (−1·88 to 0·3) | 0·241* |

| Mothers with serum retinol-binding protein results | 262 (100%) | 253 (100%) | ·· | ·· |

| Mean serum retinol-binding protein (μmol/L) | 1·23 (0·39) | 1·21 (0·34) | 0·02 (−0·05 to 0·08) | 0·566 |

| Retinol-binding protein <0·70 μmol/L | 16 (6%) | 12 (5%) | 1·36 (−2·54 to 5·27) | 0·495 |

| Retinol-binding protein <0·35 μmol/L | 0 | 0 | ·· | ·· |

Calculated with Fisher’s exact test p value.

Table 4 shows the number of adverse events within 3 days of supplementation by trial group. 246 infants died within the first 72 h of supplementation—116 (1%) in the vitamin A group and 130 (1%) in the placebo group (relative risk 0·89 [95% CI 0·70–1·15]). We noted no significant differences between the vitamin A and placebo groups in the proportion of infants who had bulging fontanelle, fever, vomiting, diarrhoea, or inability to feed. Bulging fontanelle was observed in 41 children: 21 (<1%) in the vitamin A group and 20 (<1%) in the placebo group. Five (<1%) infants in the placebo group had convulsions compared with none in the vitamin A group.

Table 4.

Adverse events within 3 days

| Vitamin A group | Placebo group | Risk ratio (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

All infants (n=31 627)

| ||||

| Death within 3 days of supplementation | 116 (0·73%) | 130 (0·82%) | 0·89 (0·7–1·15) | 0·378 |

|

| ||||

|

Infants with data for adverse events within 3 days (n=29 041)

| ||||

| Examined bulging fontanelle | 21 (0·14%) | 20 (0·14%) | 1·05 (0·57–1·94) | 0·877 |

| Fever | 174 (1·2%) | 179 (1·23%) | 0·97 (0·79–1·20) | 0·786 |

| Vomiting | 26 (0·18%) | 17 (0·12%) | 1·53 (0·83–2·82) | 0·170 |

| Diarrhoea | 3 (0·02%) | 5 (0·03%) | 0·60 (0·14–2·51) | 0·479 |

| Inability to suck or feed | 30 (0·21%) | 29 (0·2%) | 1·03 (0·62–1·72) | 0·897 |

| Convulsion | 0 (0%) | 5 (0·03%) | ·· | 0·031* |

Fisher’s exact test p value.

In the appendix we include analyses for the effect of vitamin A supplementation on adverse events using all enrolled newborn babies instead of limiting analyses to those who were assessed in the first 3 days of life (appendix). Similarly, we examined the effect of supplementation on mortality at 28 days, 6 months, and 12 months and on hospital admission at age 6 months for all enrolled infants (appendix) and person-time analyses (appendix). In all cases, the results were not substantially different from the analyses presented above. Finally, we presented the effect of neonatal vitamin A on mortality at 6 months within strata of birthweight, wealth, maternal vitamin A supplementation, and receipt of diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus 1 vaccine. There was no evidence of modification of the effect of vitamin A by any of these variables. We will further examine subgroup analyses by pooling data across the three companion trials, in which statistical power will be greater.

Discussion

Provision of one dose of vitamin A at birth was thought to be a low-cost intervention that could have significant protective effects on development of the immune system and early infant mortality.23 In this trial we did not show a beneficial effect on survival at age 6 months in infants given vitamin A supplementation within the first 3 days after birth, although the findings do not exclude the possibility of a slight increased risk of death.

Our results are consistent with a companion trial in Ghana (n=22 955),18 which reported a non-significant 12% increased risk in mortality by 6 months after vitamin A supplementation (risk ratio 1·12 [95% CI 0·95–1·33]). The results of these two new large trials are consistent with findings from a trial in Zimbabwe,15 in which the relative risk for neonatal supplementation was 1·12 (95% CI 0·80–1·57). Although the confidence intervals for the findings from our and these two trials were not significant at the conventional 5% level, the findings do not exclude the possibility of harm from neonatal vitamin A supplementation. By contrast, findings from the second companion trial in India (n=44 984)17 indicated that neonatal supplementation resulted in a non-significant reduction in mortality (relative risk 0·90 [95% CI 0·81–1·00]), consistent with findings from two previously trials in India24 and Bangladesh.12 The differences in efficacy between these trials are probably attributable to differences in background characteristics of the study population. A key element might be the prevalence of moderate or severe vitamin A deficiency, which is higher in studies that report beneficial effects.

A notable finding from our trial is that neonatal vitamin A supplementation resulted in improved vitamin A status at 3 months; however, there was no effect on vitamin A status at 2 weeks. At both timepoints, more than 50% of infants in vitamin A and placebo groups still had vitamin A concentrations below the cutoff typically suggestive of moderate deficiency (<0·7 μmol/L). The clinical importance of these findings is not clear since not many data exist about absolute serum vitamin A concentrations in infants and their relation to vitamin A status. Supplementation had little effect on serum retinol concentrations in infants at both timepoints in Ghana.18 It is plausible that the large dose of vitamin A supplementation is not optimally absorbed, possibly leading to poor clinical effect.

We did not find the effects of vitamin A to be different in boys compared with girls, contrary to reports from Guinea-Bissau by Benn and colleagues,14,25,26 who reported excess mortality among girls supplemented with vitamin A. Our results are consistent with the two companion trials17,18 and a meta-analysis.27 However, our overall findings, and the results from Ghana and Zimbabwe, do not exclude the possibility of potential harm from neonatal supplementation. Consistent with the effect of supplementation on mortality by 6 months, the relative risk of hospital admission was 1·10 (95% CI 0·94–1·28) in Tanzania, and 1·11 (95% CI 1·00–1·22) in Ghana. Pooling data across the three companion trials will provide a unique opportunity to examine potential modifiers that identify subgroups of children who might be positively or adversely affected by neonatal supplementation, including birthweight, gestational age at birth, maternal vitamin A status, and vaccine use in early infancy, among others. In our study, vitamin A supplementation in newborn infants did not result in any immediate adverse events. Rates of adverse events at 3 days after supplementation were similar between the vitamin A and placebo groups. Similar findings were reported in a meta-analysis23 and the accompanying trial from Ghana.18 By contrast, the companion trial in India17 showed a small excess risk of transient bulging fontanelle in the vitamin A supplementation group compared with the placebo group.

Panel: Research in context.

Systematic review

We searched all English language articles published in PubMed and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews between Jan 1, 1980, and Dec 31, 2013, using the search terms: “newborn”, “neonatal”, “vitamin A”, “supplementation”, “child mortality”, “individual randomised”, and “cluster randomised trials”. We manually examined the results. We reviewed published clinical trials with mortality at 6 months of age as primary endpoint. We found 39 published randomised controlled trials and meta-analyses, which showed evidence for benefits of vitamin A supplementation in children aged 6–59 months. Evidence to support whether supplementation provided similar benefits in children younger than 6 months had conflicting results, ranging from no benefit, potential benefit, or possible harm in subsets of children.

Interpretation

Supplementation of newborn babies with vitamin A on the day of birth or within the next 2 days of life did not provide a survival benefit in Tanzanian infants at 6 months of age. Vitamin A supplementation was well tolerated, and no differential effects were found between boys and girls. These findings do not support a global policy for newborn vitamin A supplementation. For global policy formulation, assessment should be done of potential modifiers from pooled data and meta-analyses from all other trials to carefully understand safety and efficacy of newborn vitamin A supplementation in subsets of children among whom the intervention might be beneficial.

Although our trial is the largest randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study on this subject in sub-Saharan Africa so far (panel) and it was designed with statistical power to ascertain a 15% effect size, mortality to age 6 months was lower than we had assumed. The most likely explanation for this low mortality is the recent increased spending on health, and improved coverage of childhood interventions (eg, insecticide-treated bednets for malaria prevention, exclusive breastfeeding, high equitable level of child immunisation) in Tanzania.28 Our study had high ascertainment of the outcomes of interest, as shown by the low loss to follow-up rates both at 6 months (3·5%) and at 12 months of age (4·8%), despite many challenges throughout the implementation of the study.

Neonatal vitamin A supplementation was not associated with any immediate adverse events. Further more, findings from this trial do not support survival benefit in infants at 6 months of age. Although the trials from Tanzania and Ghana indicate no overall benefit and some plausible risk for supplementation, for formulation of global policy, analyses of pooled data from the three large companion trials and meta-analyses of all other trials will be important to carefully understand the safety and efficacy of vitamin A supplementation in subsets of children in whom the intervention might be beneficial.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to WHO. We thank the following the health authorities in the three municipals of Ilala, Kinondoni, and Temeke in Dar es Salaam, and in Kilombero, Ulanga, and Kilosa districts in the Morogoro region; and the communities and families who participated in the trial. We thank the coordinators, supervisors, research assistants, field supervisors, field interviewers, and health and demographic surveillance system staff at Ifakara Health Institute for their commitment during the implementation of the study. Finally, we thank the ethics committees at Ifakara Health Institute, National Institute for Medical Research, Harvard School of Public Health, and members of the data safety and monitoring board (Reynaldo Martorell, chair; and Beth Akumatey, Allan Donner, Esther Mwaikambo, and Vinod Paul) for their stewardship.

Footnotes

Contributors

HM, ERS, and WWF drafted the Article, with contributions from all authors. HM, JM, RB, and WWF designed the trial. All authors participated in field implementation. ERS, PK, SY, RB, HM, and WWF contributed to statistical analyses. All authors read and approved the final version of the paper.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.UNICEF, WHO, The World Bank, UN. Levels & Trends in Child Mortality: Estimates Developed by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oestergaard MZ, Inoue M, Yoshida S, et al. Neonatal mortality levels for 193 countries in 2009 with trends since 1990: a systematic analysis of progress, projections, and priorities. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Black RE, et al. What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. Lancet. 2008;371:417–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61693-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. A global agenda for combating malnutrition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. Nutrition for Health and Development. [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. WHO global database on vitamin A deficiency. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Global prevalence of vitamin A deficiency in populations at risk 1995–2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imdad A, Herzer K, My Y, Za B. Vitamin A supplementation for preventing morbidity and mortality in children from 6 months to 5 years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;12:CD008524. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008524.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fawzi WW, Chalmers TC, Herrera MG, Mosteller F. Vitamin A supplementation and child mortality. A meta-analysis. JAMA. 1993;269:898–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glasziou PP, Mackerras DE. Vitamin A supplementation in infectious diseases: a meta-analysis. BMJ. 1993;306:366–70. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6874.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO/UNICEF/VACG Task Force. A guide to their use in the treatment and prevention of vitamin A deficiency and xerophthalmia. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. Vitamin A supplements. [Google Scholar]

- 10.West KP, Katz J, Shrestha SR, et al. Mortality of infants <6 mo of age supplemented with vitamin A: a randomized, double-masked trial in Nepal. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;62:143–48. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/62.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahmathullah L, Tielsch JM, Thulasiraj RD, et al. Impact of supplementing newborn infants with vitamin A on early infant mortality: community based randomised trial in southern India. BMJ. 2003;327:254. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7409.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klemm RDW, Labrique AB, Christian P, et al. Newborn vitamin A supplementation reduced infant mortality in rural Bangladesh. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e242–50. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Humphrey JH, Agoestina T, Wu L, et al. Impact of neonatal vitamin A supplementation on infant morbidity and mortality. J Pediatr. 1996;128:489–96. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70359-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benn CS, Fisker AB, Napirna BM, et al. Vitamin A supplementation and BCG vaccination at birth in low birthweight neonates: two by two factorial randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1101. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malaba LC, Iliff PJ, Nathoo KJ, et al. Effect of postpartum maternal or neonatal vitamin A supplementation on infant mortality among infants born to HIV-negative mothers in Zimbabwe. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:454–60. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.81.2.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bahl R, Bhandari N, Dube B, et al. Efficacy of early neonatal vitamin A supplementation in reducing mortality during infancy in Ghana, India and Tanzania: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13:22. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazumder S, Taneja S, Bhatia K, et al. for the Neovita India Study Group. Efficacy of early neonatal supplementation with vitamin A to reduce mortality in infancy in Haryana, India (Neovita): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60891-6. published online Dec 11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60891-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Edmond KM, Newton S, Shannon C, et al. Effect of early neonatal vitamin A supplementation on mortality during infancy in Ghana (Neovita): a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60880-1. published online Dec 11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60880-1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.INDEPTH, Network. Population, health, and survival at INDEPTH sites. Vol. 1. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre; 2002. Population and health in developing countries. [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Brien PC, Fleming TR. A multiple testing procedure for clinical trials. Biometrics. 1979;35:549–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data—or tears: an application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography. 2001;38:115–32. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:e1–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gogia S, Sachdev HS. Vitamin A supplementation for the prevention of morbidity and mortality in infants six months of age or less. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;10:CD007480. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007480.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahmathullah L, Tielsch JM, Thulasiraj RD, et al. Impact of supplementing newborn infants with vitamin A on early infant mortality: community based randomised trial in southern India. BMJ. 2003;327:254. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7409.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benn CS, Diness BR, Roth A, et al. Effect of 50 000 IU vitamin A given with BCG vaccine on mortality in infants in Guinea-Bissau: randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;336:1416–20. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39542.509444.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benn CS, Fisker AB, Napirna BM, et al. Vitamin A supplementation and BCG vaccination at birth in low birthweight neonates: two by two factorial randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2003;327:254. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirkwood B, Humphrey J, Moulton L, Martines J. Neonatal vitamin A supplementation and infant survival. Lancet. 2010;376:1643–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61895-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masanja H, de Savigny D, Smithson P, et al. Child survival gains in Tanzania: analysis of data from demographic and health surveys. Lancet. 2008;371:1276–83. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60562-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.