Abstract

The lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and O-antigen polysaccharide capsule structures of Francisella tularensis play significant roles in helping these highly virulent bacteria avoid detection within a host. We previously created pools of F. tularensis mutants that we screened to identify strains that were not reactive to a monoclonal antibody to the O-antigen capsule. To follow up previously published work, we characterize further seven of the F. tularensis Schu S4 mutant strains identified by our screen. These F. tularensis strains carry the following transposon mutations: FTT0846::Tn5, hemH::Tn5, wbtA::Tn5, wzy::Tn5, FTT0673p/prsA::Tn5, manB::Tn5, or dnaJ::Tn5. Each of these strains displayed sensitivity to human serum, to varying degrees, when compared to wild-type F. tularensis Schu S4. By Western blot, only FTT0846::Tn5, wbtA::Tn5, wzy::Tn5, and manB::Tn5 strains did not react to the capsule and LPS O-antigen antibody 11B7, although the wzy::Tn5 strain did have a single O-antigen reactive band that was detected by the FB11 monoclonal antibody. Of these strains, manB::Tn5 and FTT0846 appear to have LPS core truncations, whereas wbtA::Tn5 and wzy::Tn5 had LPS core structures that are similar to the parent F. tularensis Schu S4. These strains were also shown to have poor growth within human monocyte derived macrophages (MDMs) and bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs). We examined the virulence of these strains in mice, following intranasal challenge, and found that each was attenuated compared to wild type Schu S4. Our results provide additional strong evidence that LPS and/or capsule are F. tularensis virulence factors that most likely function by providing a stealth shield that prevents the host immune system from detecting this potent pathogen.

Keywords: Francisella tularensis, O-antigen, capsule, transposon mutagenesis, innate immunity, intracellular growth, mouse virulence

Introduction

Francisella tularensis is the causative agent of the human disease tularemia. This small Gram negative organism is able to cause disease with as few as 10 colony forming units (CFU) when inhaled, and without treatment, upwards of 60% of those infected may die (Saslaw et al., 1961; Tarnvik and Berglund, 2003; Oyston, 2008). Due to the ease of aerosolization, low infectious dose, and potentially high fatality rates, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has classified F. tularensis has a Tier I select agent (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Although, there are relatively few naturally acquired Francisella infections per year in the United States (Carvalho et al., 2014), a primary concern is that the organism will be used in a bioterrorist attack. This is not an unfounded concern as Francisella species were weaponized by Japan, United States, and the former U.S.S.R., during and after World War II (Oyston et al., 2004; Sjostedt, 2007). These concerns have highlighted the need to develop a vaccine to prevent disease and associated deaths from the potential use of Francisella as a bioterrorist weapon.

Although essential genes for bacterial growth and replication have been identified as important for Francisella to cause productive infection, few other genes have been clearly linked to pathogenesis. Our studies of F. tularensis waaY and waaL mutants have previously demonstrated that LPS associated O-antigen and capsule have significant roles in the pathogenesis of F. tularensis Schu S4 (Lindemann et al., 2011; Rasmussen et al., 2014). These genes function in LPS assembly by participating in the LPS core construction (waaY) and in ligating the tetrasaccharide O-antigen repeats to LPS core (waaL) (Rasmussen et al., 2014). In addition, a number of other labs have shown that strain with mutations in genes that are involved in capsule and LPS biosynthesis have significantly altered virulence properties (Sandstrom et al., 1988; Comstock and Kasper, 2006; McLendon et al., 2006; Barker and Klose, 2007; Su et al., 2007; Weiss et al., 2007; Apicella et al., 2010). Strains carrying mutations in either of these genes enter into human MDMs at elevated levels, are cytotoxic for MDMs at early time points, and are much more sensitive to human serum than the parent Schu S4 strain (Lindemann et al., 2011). These data suggest that one of the significant functions of the O-antigen structures of both the Francisella LPS and capsule are to provide stealth concealment for the organism, allowing it to avoid detection by the host. This is not a novel strategy to avoid host recognition, as it has been described in some detail for other Gram-negative organisms (Comstock and Kasper, 2006). Interestingly, even though the waaY or waaL mutants lack O-antigen and capsule and are hypercytotoxic in MDMs (Lindemann et al., 2011), these strains still disseminate to the livers and spleens of mice during infection but cause death by a different mechanism than wild type F. tularensis (Rasmussen et al., 2014). These data imply that F. tularensis expresses antigens that can induce host inflammation, but that they are obscured by the LPS and capsule in wild type organisms. The virulence still possessed by the F. tularensis O-antigen mutants is unusual since O-antigen mutants in other species of bacteria are typically avirulent (Rietschel, 1984; Iredell et al., 1998; Prior et al., 2003; Ho and Waldor, 2007; Sheng et al., 2008; Post et al., 2012).

An interesting aspect of the F. tularensis capsule is that the polysaccharide repeat structure is exactly the same as the LPS O-antigen (Vinogradov et al., 2002; Thomas et al., 2007; Apicella et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011). While the O-antigen structure is the same, F. tularensis capsule is assembled without core LPS sugars, 2-keto-3-deoxyoctulsonic acid (KDO), or lipid A (Apicella et al., 2010). Due to the identical tetrasaccharide repeat containing acetimido sugars and high molecular weight structure, F. tularensis capsule is considered to be a Group 4 capsule (Whitfield, 2006). Studies of Group 4 capsules in other organisms have revealed distinct LPS and capsule biosynthetic pathways (Whitfield, 2006). To date, however, divergent biosynthetic pathways for F. tularensis LPS and capsule have not been discovered. Although extensive analysis of O-antigen biosynthesis has not been done in Francisella, LVS strains with mutations in the wbt genes do not produce O-antigen (Raynaud et al., 2007). In addition, wbt mutant strains are also more susceptible to complement-mediated lysis than F. tularensis LVS (Li et al., 2007; Clay et al., 2008). Strains carrying either a waaY or waaL mutation display moderate attenuation in an intranasal infection (i.n.) as seen by the 1000-fold and 100-fold increase in the LD50, respectively (Rasmussen et al., 2014), compared to the F. tularensis Schu S4 theoretical LD50 of ~1 CFU (Kim et al., 2012). When infected intraperitoneally (i.p.) the mutants are significantly attenuated (more than a 100,000 fold increase in comparison to the wild type LD100 of ~1 CFU), as would be expected for traditional waa mutants (Rietschel, 1984).

We screened a F. tularensis Schu S4 mutant library of ~7500 mutants by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to identify strains defective for capsule production (Rasmussen et al., 2014). From that screen we identified six strains with mutations in genes FTT0846, FTT1138 (hemH), FTT1236 (waaY), FTT1238c (waaL), FTT1464c (wbtA), and FTT1458c (wzy) that had significantly less capsule compared to the parent strain, as detected by a lack of binding to the anti-capsule mAb (11B7) (Rasmussen et al., 2014). Mutation of these genes also caused decreased binding of the anti-O-antigen mAb (FB11) as detected by ELISA (Rasmussen et al., 2014). In a second screen, we identified three additional mutant strains FTT1447c (manB), FTT1512c (dnaJ) and an intergenic insertion between FTT0673 and FTT0674c (prsA) that also had decreased amounts of detectable capsule.

Although we have previously characterized the F. tularensis waaY and waaL mutants in some detail, this manuscript describes our work characterizing the additional F. tularensis strains with O-antigen defects that map to dnaJ, hemH, manB, wbtA, wzy, FTT0846, and FTT0673p/prsAp::Tn5. We present data on the serum sensitivity of these strains, characteristics of the capsule/O-antigen and LPS core of each strains, the ability to grow in murine bone marrow derived macrophages and human macrophages, and attenuation for virulence in a murine infection model. We have found that mutations in dnaJ, hemH, and the FTT0673p/prsAp::Tn5 strain did not have significant differences in many of the assays performed, whereas the strains with mutations in manB, wzy, wbtA, and FTT0846 display phenotypes similar to those observed for the F. tularensis waaY and waaL mutants.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains, plasmid construction, and growth conditions

F. tularensis subsp. tularensis Schu S4 was routinely cultured on Modified Mueller Hinton (MMH) plates (Acumedia, Lansing, MI) or in MMH broth. Schu S4 mutant strains were grown on MMH plates supplemented with 50 μg/ml of kanamycin as needed. Complementation was performed by cloning the coding sequence of a gene downstream of the constitutive Pgro promoter into pTrc99A. Primers used to amplify functional wzy and manB genes for complementation are respectively, wzy: Forward, 5′-GGATCCGGTACCGTGTACATAAAAAAAGTGTCTTTTAAAATT-3′ and Reverse, 5′-GTCGACAAGGTTTATTATTAAATGTACAAACC-3′. manB: Forward, 5′-GGATCCGGTACCATGAGACAAACTATAATAAAAGAAATAATC-3′ and Reverse, 5′-GTCGACAGAAAGTTAGGGAATATTTTTGACTG-3′. The promoter-gene construct was then cloned into the Francisella shuttle vector, pBB103 (Buchan et al., 2008) and cryotransformed into mutant strains as previously described (Buchan et al., 2008). Complemented strains were grown on MMH plates or in MMH broth supplemented with 50 μg/ml of spectinomycin. All work with F. tularensis Schu S4 was performed within the Carver College of Medicine Biosafety Level 3 (BSL3) Core Facility and experimental protocols were reviewed for safety by the BSL3 Oversight Committee of The University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine. Recombinant DNA work with F. tularensis Schu S4 was reviewed and approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Biosafety Committee.

In vitro growth assay

To determine whether F. tularensis mutant strains exhibited growth defects compared to wild type Schu S4, wild type and mutants were grown to saturation with shaking at 37°C and diluted into fresh MMH broth to an OD600 of 0.1. Broth cultures were shaken at 200 rpm at 37°C, and the optical density was determined at intervals. The doubling time (T) was calculated using the formula N = Nkt0e, where T = (ln 2)/k, and growth indices were calculated by taking the same time points in the linear range for comparison (t is time, N is the amount after t, N0 is the initial amount, and k is the constant rate of growth).

Serum sensitivity assay

After obtaining informed consent, human serum was obtained from 15 to 20 individuals with no known history of tularemia and then pooled following the protocol (#200307026) approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) for human subjects of the University of Iowa. Bacteria were grown in MMH broth (with 50 μg/ml of spectinomycin for complemented mutants) for ~18 h at 200 rpm at 37°C. Bacteria were quantitated by measuring the OD600. Bacteria were added to PBS to make a culture of 1 × 107 CFU/ml in 50% pooled normal human serum and incubated with shaking at 37°C for 90 min. Before and after incubation, bacteria were serially diluted in PBS, plated on MMH plates (with spectinomycin as needed), and grown for 2 days at 37°C with 5% CO2. Strains were serially diluted and plated for inputs and also after serum treatment to determine percentage of survivability.

Page, immunoblotting and Emerald green stain of bacterial whole cell lysates

Francisella strains from freshly streaked agar plates were inoculated into MMH broth and grown for 24 h before the OD600 was measured and recorded. One ml broth cultures were centrifuged at 8000x g for 1 min before the pellet was resuspended in Buffer Part A, [6 mM Tris, 10 mM EDTA, and 2% (wt/vol) SDS (pH 6.8)] and heated to 65°C to sterilize cultures. Bacterial lysates were incubated with proteinase K (New England Biolabs, Ipswitch, MA) at 37°C for 24 h before lyophilizing. Approximately 5 μg of bacterial material from each sample was mixed with NuPage (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) sample reducing agent and buffer, boiled for 10 min, and loaded into a 4–12% Bis-Tris NuPage gel and separated by electrophoresis using NuPage MES SDS running buffer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). For immunoblots, samples separated by PAGE were transferred to nitrocellulose using a semi-dry transfer system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The nitrocellulose membrane was blocked in blocking buffer (5% BSA in PBS) and then incubated with either primary mAb 11B7 (Dr. Apicella, University of Iowa, IA) to detect capsule, or mAb FB11 to detect LPS O-antigen (QED Bioscience, San Diego, CA). Bands were visualized using goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) and SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). The ProQ-Emerald 300 stain was used to visualize carbohydrates and the protocol was followed according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA).

Isolation and culture of human and murine macrophages

Venous blood was drawn from healthy adult volunteers using a protocol approved by The University of Iowa Institutional Review Board (IRB) for Human Subjects at the University of Iowa, and all subjects provided informed consent. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated as described previously (Schulert and Allen, 2006). Briefly, PBMCs were isolated from venous blood by centrifugation on Ficoll-Hypaque (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ), washed twice in HEPES-buffered RPMI 1640 with L-glutamine (RPMI) (Lonza, Walkersville, MD), seeded into Teflon jars at 2 × 106 cells/ml, and allowed to differentiate into MDMs for 5 to 7 days in RPMI 1640 plus 20% autologous serum at 37°C with 5% CO2.

To isolate BMDMs, 6–8 week old BALB/c female mice were purchased from Frederick National Cancer Institute (NCI, Frederick, MD) and femurs were harvested and flushed with Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were grown in DMEM with 20% L929 cell-conditioned media, 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and supplemented with 100 μg/ml of streptomycin and 100 U/ml of penicillin. Cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 5–7 days until monolayers of macrophages were detected.

Human and murine intramacrophage growth

To quantify the extent of intracellular replication, MDMs were plated in Costar 24-well dishes (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at a density of 1–2×105 cells/well and allowed to adhere overnight at 37°C. Monolayers were washed with warm PBS twice, and infected in duplicate or triplicate with unopsonized wild-type Schu S4 or mutant strains in RPMI plus 2.5% heat-inactivated (56°C, 30 min) pooled human serum at an MOI of 100:1. After 1 h at 37°C, monolayers were washed three times with PBS to remove extracellular bacteria, and fresh RPMI plus 2.5% heat inactivated normal human serum was added. Wells were lysed in 0.5% saponin at 1, 16, and 24 h post-infection. Lysates were serially diluted in PBS, and viable bacteria were enumerated by plating on MMH agar as described above. BMDM infections using the appropriate media were done similarly to the human MDM infections. BMDMs were plated at a density of 3 × 105 cells/well and infected at an MOI of 100:1.

Confocal microscopy

Macrophages infected with F. tularensis were processed for microscopic analysis as previously described (Allen and Aderem, 1996) with minor modifications. Cells were fixed in 10% formalin, permeabilized by the addition of -20°C acetone and methanol (1:1), and blocked at 4°C for 5 days in PBS plus 0.5 mg/ml sodium azide, 5 mg/ml BSA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and 10% horse serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Parallel samples were lysed and examined for sterility so that experimental samples could be removed from the BSL-3 facility. The rabbit anti-F. tularensis antiserum (BD Diagnostics, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and Dyelight 549-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG F(ab')2 secondary antibody from Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories (West Grove, PA) were used to detect wild type and mutant strains. The late endosome/lysosome-associated membrane protein-1 (lamp-1) was detected using a mouse anti-human lamp-1 monoclonal antibody (H4A3) from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at the University of Iowa (IA, Iowa City) and Dyelight 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG F(ab')2 secondary antibody (Jackson Immuno Research, West Grove, PA). Images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM-510 confocal microscope using Zen software (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY).

Murine infections and organ burden

BALB/c female mice, 6–8 weeks of age, were purchased from NCI for all sets of animal experiments. Groups of five mice were used for evaluation of virulence (determining the LD50) of Francisella strains and groups of six mice were used for experiments in which bacterial growth in murine organs was examined. Mice anesthetized with isoflurane (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) vapor were infected intranasally with 50 μl inocula mixed in PBS and were monitored for up to 26 days post-infection for the virulence studies. Doses ranging from 101 to 105 CFU were estimated from OD600 readings and were confirmed by serial dilution and plating of the bacterial suspension. For determination of bacterial burden in organs, mice were infected as described above, with mutant strains at approximately 5- 20-fold lower than the LD50 dose for each strain. Lungs, livers and spleens were harvested 40 days post-infection. Organs were homogenized using 50 mL tissue grinders (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) in 2 ml of 1% saponin (ACROS, New Jersey). Organ homogenates were serially diluted in PBS and plated to enumerate the bacterial load per organ. All work with F. tularensis Schu S4 was performed within the Carver College of Medicine Biosafety Level 3 (BSL3) Core Facility, and all experimental protocols were reviewed for safety by the BSL3 Oversight Committee of the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine. Recombinant DNA work with F. tularensis Schu S4 was approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee.

Results

Identification of F. tularensis genes involved in capsule and O-antigen synthesis

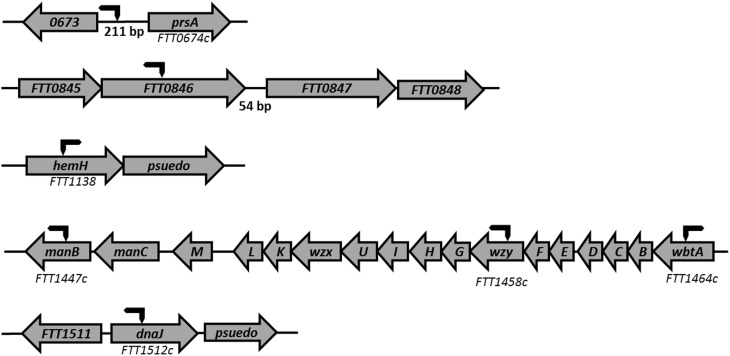

A total of nine strains were identified by screening a Tn5 transposon library of F. tularensis Schu S4 with monoclonal antibodies produced against F. tularensis capsule preparations. The mutations in three strains, FTT0673p/prsA::Tn5, manB, and dnaJ, were identified as important in capsule biosynthesis as the strains displayed reduced binding to the mAb 10E8. In a second screen, using high affinity mAb 11B7, six strains with mutations in FTT0846, hemH, waaY, waaL, wbtA, or wzy were independently identified as having a role in capsule biosynthesis. The chromosomal locations of the genes were identified by rescue cloning of the transposon insertion site and sequencing of the flanking chromosomal DNA (Rasmussen et al., 2014). The sites of the transposon insertions are shown in Figure 1. The FTT0673, prsA, FTT0846, and hemH genes that we have identified here have not been targeted for mutation or identified in previous genetic screens of Francisella. However, the genes waaY (Weiss et al., 2007; Lindemann et al., 2011; Case et al., 2013), waaL (Maier et al., 2007; Weiss et al., 2007; Lindemann et al., 2011), wbtA (Maier et al., 2007; Su et al., 2007), wzy (Lindemann et al., 2011), and manB (Weiss et al., 2007; Lindemann et al., 2011; Case et al., 2013) genes have been previously identified as important for Francisella virulence. Although the dnaJ gene has not been identified previously as important in virulence, its transcription has been reported to increase during F. tularensis intracellular growth (Wehrly et al., 2009). Growth rates were determined for all of the mutant strains and were found to be similar to wild type Schu S4 (Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Chromosomal location of Tn5 insertions. Seven mutant strains that were disrupted in genes important for capsule production, were identified from the screened Schu S4 library using the capsule mAbs 11B7 and 10E8. Rescue cloning was performed and the plasmids obtained were sent to The University of Iowa School of Medicine DNA Core for sequencing. A Tn5 primer was used to sequence the F. tularensis chromosomal DNA flanking the Tn5 transposon insertion. One end of the arrow shows the approximate site of transposon insertion into the chromosome and the arrow to the left or right shows the direction of the transposon element.

Characterization of the LPS and capsule structures of F. tularensis mutants

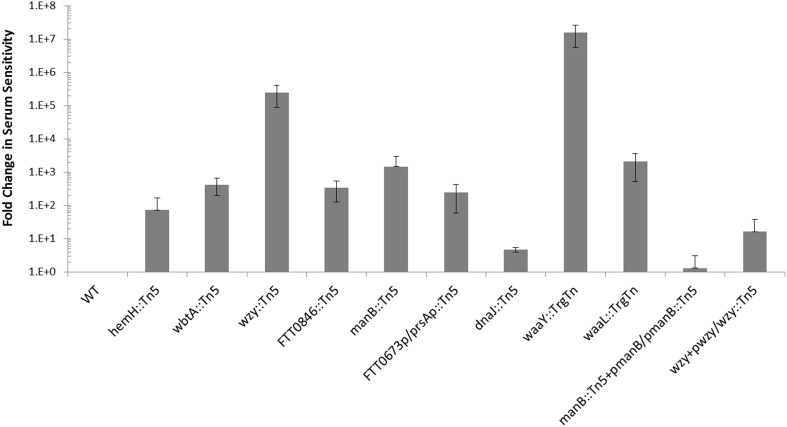

We have shown previously that mutations in some F. tularensis genes important for O-antigen and capsule biosynthesis result in sensitivity to human serum complement (Lindemann et al., 2011). Serum sensitivity was tested for the F. tularensis strains with mutations in dnaJ::Tn5, hemH::Tn5, manB::Tn5, wbtA::Tn5, FTT0846::Tn5, or FTT0673p/prsAp::Tn5 by exposing them to 50% pooled human serum for 90 min at 37°C. Each of the mutants displays some degree of serum sensitivity when compared to wild type (Figure 2). The fold increase in serum sensitivity of each F. tularensis mutant strain, compared to wild type was ~5 for dnaJ1::Tn5, ~70 for hemH::Tn5, ~245 for FTT0673p/prsAp::Tn5, ~330 for FTT0846, ~425 for wbtA::Tn5, ~1.5 × 103 for manB::Tn5, ~2 × 103 for waaL::TrgTn, 2.4 × 104 for wzy::Tn5, and ~1.6 × 107 for waaY::TrgTn. These results provided further evidence that the mutated genes are involved in LPS biosynthesis, capsule biosynthesis, or biosynthesis of an outer membrane component since these structures are known to affect serum sensitivity. An effort was made to complement each of the mutant strains back to a wild type phenotype but we were only able to restore functions in the wzy and manB mutants. Complementation of the wzy or the manB mutation restored serum resistance ~ 500- and ~8.5 × 103-fold, respectively (Figure 2). Difficulty in complementing mutants in Francisella has been reported by several other F. tularensis research groups (Maier et al., 2004; Zogaj and Klose, 2010; de Bruin et al., 2011).

Figure 2.

Comparison of serum sensitivity of mutants to wild type Schu S4. The serum sensitivity of F. tularensis mutants and complemented mutants is compared to wild type and is displayed as fold-change. Data were normalized to wild type. F. tularensis strains were prepared identically, exposed to pooled human serum for 90 min and then serially diluted.

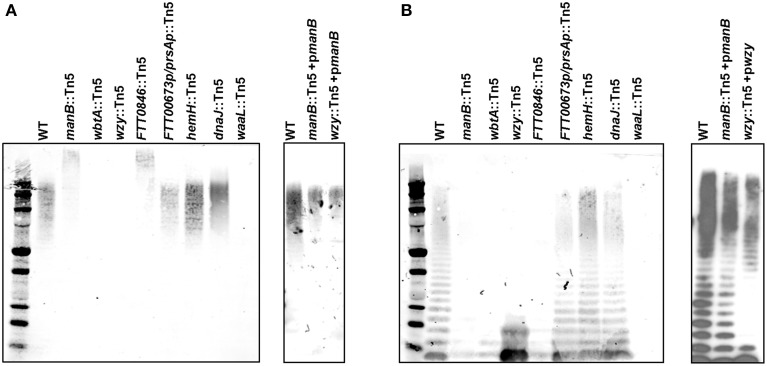

To more thoroughly characterize the LPS and capsule produced by each mutant, whole cell lysates were prepared from each strain and treated with proteinase K. The lysates were run on an SDS-PAGE gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with the anti-O-antigen (FB11) and anti-capsule antibodies (11B7). The anti-capsule immunoblot revealed that both the wbtA and wzy mutants lacked detectable capsule whereas the FTT0846 and manB mutants had altered capsule species that were of higher molecular weight than wild-type Schu S4 capsule. Additionally, the altered capsules were less abundant than that of wild type Schu S4. The dnaJ::Tn5, hemH::Tn5, or FTT0673p/prsAp::Tn5 mutants appeared to produce capsule in similar amounts to the parent strain (Figure 3). The anti-O-antigen immunoblot revealed that the wbtA, FTT0846, and manB mutants did not show LPS O-antigen laddering, whereas the wzy mutant produced a truncated LPS associated O-antigen structure, containing just one or two O-antigen subunits. This latter phenotype has been previously reported for an LVS wzy mutant (Kim et al., 2010). The dnaJ, hemH, and FTT0673/prsA intergenic mutants did not display any detectable difference in O-antigen laddering in comparison to wild type. Restoration of capsule production and LPS O-antigen laddering were observed for both the wzy and manB complemented mutants (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Capsule and LPS O-antigen phenotypes of mutant strains. Bacteria were grown in MMH broth for ~24 h and lysed with Buffer Part A at 65°C. (A) The anti-capsule mAb (11B7) was used to detect capsule in whole cell lysates of wild type F. tularensis, O-antigen mutants, and complemented mutant strains by immunoblotting. (B) To detect LPS in immunoblots of whole cell lysates of wild type, mutants, and complemented mutants using the anti-O-antigen mAb (FB11).

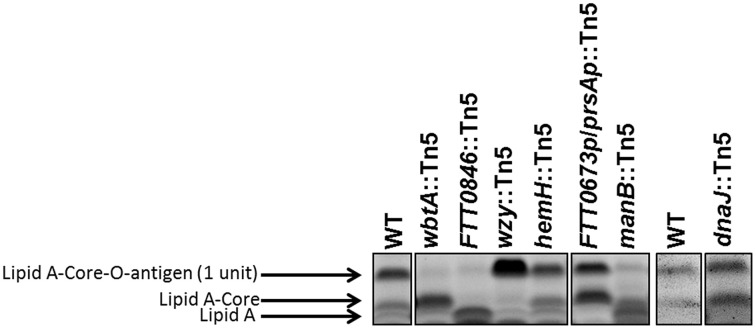

We have shown previously that mutations in the Francisella waaY and waaZ genes result in LPS core truncations, in addition to capsule and O-antigen defects (Rasmussen et al., 2014). Based upon those observations, whole cell lysates from the dnaJ::Tn5, hemH::Tn5, manB::Tn5, wbtA::Tn5, FTT0846::Tn5, and FTT0673p/prsAp::Tn5 mutant strains were stained for the presence of carbohydrates to determine if the strains carried defects in the core of the LPS. Mutants in hemH, dnaJ1, wbtA, and wzy did not appear to have core defects, as the core structures appeared to be the same as the F. tularensis Schu S4 parent, whereas the FTT0846 and manB mutants LPS core structures were either truncated or lacking (Figure 4). If the core structure is lacking for these mutants it is likely that the band observed is free lipid A.

Figure 4.

Lipopolysaccharide core structures of mutant strains. An SDS-PAGE gel was loaded with ~14 μg of dried material per mutant per well. The gel was stained with Emerald green, and is labeled to indicate lipid A—core—O-antigen (one unit), lipid A—core (no O-antigen subunit), or free lipid A (indicated by black arrows).

Determining in vitro growth phenotypes of mutants in human MDMs and murine BMDMs

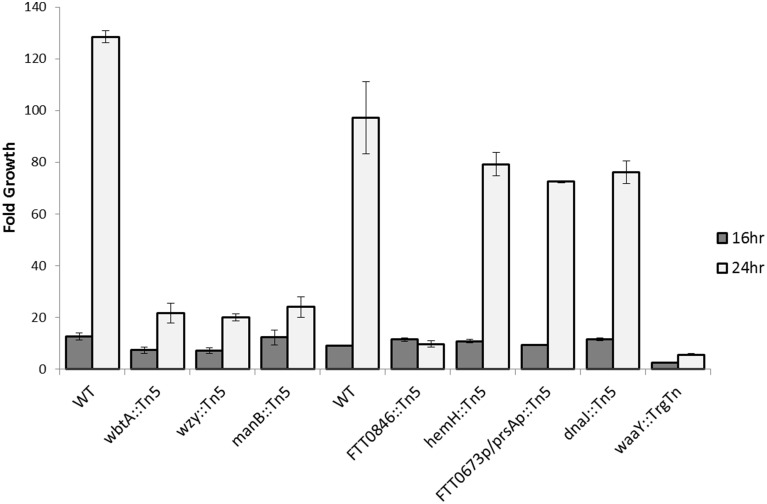

Since our previous work has shown that F. tularensis strains defective in LPS and/or capsule O-antigen biosynthesis have growth defects in human MDMs (Lindemann et al., 2011), we examined whether the strains that are the subject of this work display a similar phenotype in either MDMs or BMDMs. Due to the serum sensitivity of the mutants, a low percentage of heat-inactivated pooled human serum was used in the tissue culture media of the MDMs to prevent serum-induced killing of the bacteria. MDMs were infected at an MOI of 100:1 with wild type Schu S4, wbtA::Tn5, wzy::Tn5, manB::Tn5, FTT0846::Tn5, hemH::Tn5, FTT0673p/prsAp::Tn5, dnaJ::Tn5, and waaY::TrgTn as a negative control. Due to the number of strains being tested, we separated the strains into two separate groups (Group 1—wild type, wbtA::Tn5, wzy::Tn5 and manB::Tn5 and Group 2—wild type, FTT0846::Tn5, hemH::Tn5, FTT0673p/prsAp::Tn5 and dnaJ::Tn5) to perform human MDM infection and growth assays. Time points were taken at 1, 16, and 24 h post-infection to determine how many bacteria were present in the MDM host cells at each time point so that growth within the cells could be calculated. In contrast to the phenotype of waaY, waaZ, and waaL mutants, which exhibit increased uptake into MDMs (although overall growth of these strains was comparable to Schu S4 until 16 h) (Lindemann et al., 2011), the seven new mutants tested did not differ significantly in uptake or in growth rate up to 16 h post-infection (Figure 5). However, at the 24 h time point it was clear that strains with mutations in wbtA, wzy, manB, and FTT0846 did not increase in number compared to the 16 h time point while wild type strain continued to replicate rapidly. This is a similar phenotype to that observed with the waaL, waaY, and waaZ mutants, as growth was limited from 16 to 48 h post-infection (Lindemann et al., 2011). Not surprisingly, the hemH, dnaJ, and the intergenic FTT0673/prsA mutants did not differ considerably from wild type for growth in MDMs, since the LPS, capsule and core sugar properties of these strains were not significantly different from the parent Schu S4 (Figure 5 and Figure S2). Since the hemH, dnaJ, and the intergenic FTT0673/prsA mutants did not have significant differences in LPS, capsule or core sugar properties, or growth in MDMs, we focused our efforts on characterizing the other mutants in more detail.

Figure 5.

Intracellular growth of wbtA, wzy, manB, 0846, hemH, dnaJ, waaY, and 0673/prsA intergenic mutants in MDMs. Triplicate wells containing human macrophages were infected for 1 h with unopsonized Schu S4 or mutant bacteria, washed to remove extracellular organisms, and then lysed with 1% saponin at 1, 16, and 24 h post infection to enumerate viable bacteria. Data presented show fold growth change from 1–16 h post-infection to 1–24 h post-infection. Data are from one experiment representative of three different experiments.

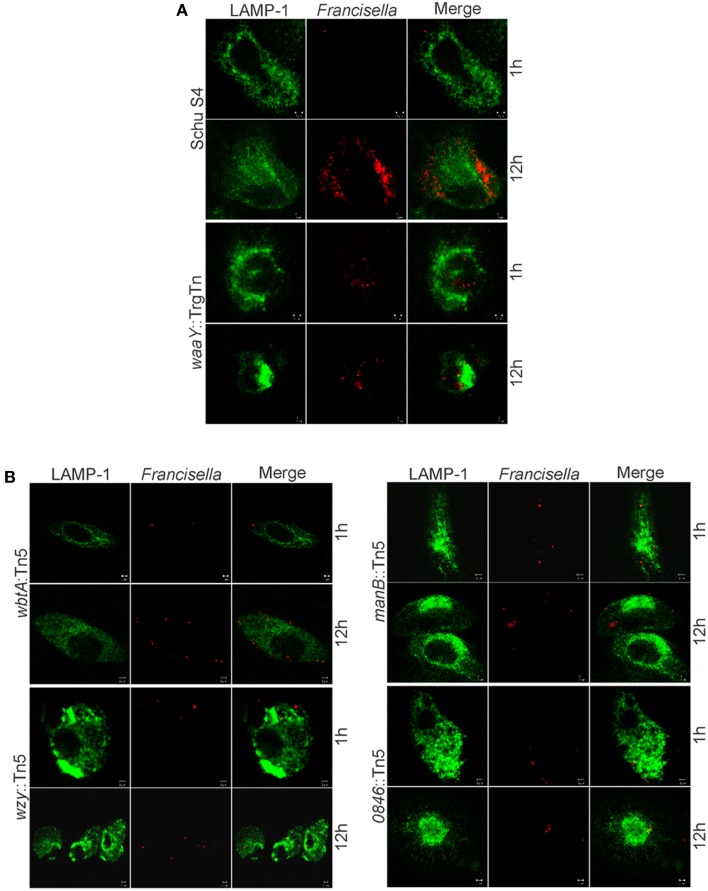

In addition to the intracellular MDM growth assay, mutant strains were also analyzed by confocal microscopy. Macrophages were infected at an MOI of 100:1 with wild type Schu S4 and mutant strains. The confocal microscopy data suggest that wbtA::Tn5, wzy::Tn5, manB::Tn5 and FTT0846::Tn5 strains were phagocytosed to the same extent as wild type, and did not colocalize with the Lamp-1 lysosomal marker, despite diminished intracellular growth at later stages of infection (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Microscopy of infected MDMs with wbtA, wzy, manB, and FTT0846 mutants. Confocal images show Lamp-1 in green and bacteria in red. MDMs were infected with (A) wild type Schu S4 as the positive control, waaY::TrgTn as a negative control, and with (B) wbtA::Tn5, wzy::Tn5, manB::Tn5, or FTT0846::Tn5 strains at an MOI of 100:1. Samples were fixed and processed at 1 and 12 h post infection.

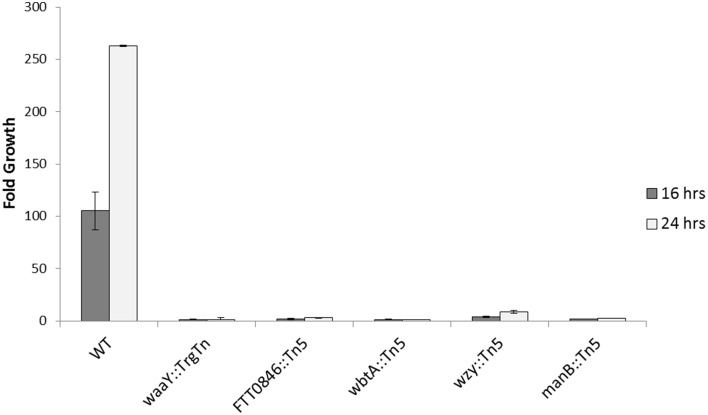

Similar to the human MDM experiments, the BMDMs were infected at an MOI of 100:1, using heat-inactivated serum, and growth data was collected 1, 16, and 24 h post-infection. The data revealed that the FTT0846::Tn5, manB::Tn5, and the negative control, waaY::TrgTn appeared to infect BMDMs slightly better than wild type; whereas, wbtA::Tn5 and wzy::Tn5 appeared to have similar entry levels into murine BMDMs. Regardless of uptake efficiency, none of the F. tularensis mutants was able to replicate within the BMDMs to any significant extent over the course of the 24 h infection (Figure 7 and Figure S3). These data suggest that the internalized organisms were viable but were unable to grow in murine macrophages.

Figure 7.

Intracellular growth of FTT0846, wbtA, wzy, and manB mutants in BMDMs. Murine macrophages were infected for 1 h with unopsonized Schu S4 or mutant bacteria, washed to remove extracellular organisms, and then lysed with 0.5% saponin at 1, 16, and 24 h post infection to enumerate viable bacteria. Data presented shows fold growth change from 1–16 h post infection to 1–24 h post infection. Data are from one experiment that is representative of three experiments.

Determination of virulence and organ dissemination in murine infections

In an effort to extend these observations and test the effects of the mutations on mouse virulence, mice were infected intranasally with F. tularensis Schu S4 (23 CFU), or with F. tularensis mutant strains, dnaJ::Tn5, hemH::Tn5, manB::Tn5, wbtA::Tn5, wzy::Tn5, FTT0673p/prsAp::Tn5, and FTT0846::Tn5 with doses ranging from 101 to 105 CFU. As was observed before during murine infections with the waaY and waaL mutants (Rasmussen et al., 2014), mice infected with manB, wbtA, wzy, or FTT0846 mutants displayed piloerection (ruffled fur) and lethargy as early as 24 h post-infection regardless of dose. These observations are in contrast to what was observed with mice infected with wild type, dnaJ::Tn5, hemH::Tn5, or FTT0673p/prsAp::Tn5. Those mice did not appear sick until 72–96 h post-infection. Mice infected with the intergenic FTT0673/prsA, dnaJ, or hemH mutants did not survive any of the doses tested (Table 1), indicating that these strains retain virulence similar to parent F. tularensis Schu S4, as mutant-infected mice died on a similar time frame as wild type. Using the Muench and Reed calculation method (Reed and Muench, 1938), we determined the i.n. LD50 values to be 5 × 103 for manB::Tn5, 2.6 × 102 for wbtA::Tn5, 1.2 × 104 for wzy::Tn5, and 1.5 × 103 CFU for FTT0846::Tn5 (Table 1 and Figure S4).

Table 1.

Murine virulence studies and experimentally determined intranasal LD50 values for F. tularensis Schu S4 and capsule and/or LPS mutants.

| Strain | Infection dose (CFU) | Survival ratio | Mean TTD | Calc LD50 (CFU) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INTRANASAL | ||||

| WT | 23 | 0/5 | 5 | <23 |

| dnaJ::Tn5 | 1.0 × 102 | 0/5 | 4.8 | <100 |

| dnaJ::Tn5 | 1.0 × 1.03 | 0/5 | 4.8 | |

| dnaJ::Tn5 | 1.0 × 104 | 0/5 | 4.4 | |

| dnaJ::Tn5 | 1.0 × 105 | 0/5 | 4 | |

| hemH::Tn5 | 1.1 × 102 | 0/5 | 6 | <110 |

| hemH::Tn5 | 1.1 × 103 | 0/5 | 5 | |

| hemH::Tn5 | 1.1 × 104 | 0/5 | 4.2 | |

| hemH::Tn5 | 1.1 × 105 | 0/5 | 4 | |

| manB::Tn5 | 1.0 × 102 | 5/5 | >27 | 5 × 103 |

| manB::Tn5 | 1.0 × 103 | 5/5 | >27 | |

| manB::Tn5 | 1.0 × 104 | 0/5 | 7.6 | |

| manB::Tn5 | 1.0 × 105 | 0/5 | 6.6 | |

| wbtA::Tn5 | 1.8 × 101 | 4/4 | >27 | 2.6 × 102 |

| wbtA::Tn5 | 1.8 × 102 | 3/5 | >27 | |

| wbtA::Tn5 | 1.8 × 103 | 0/5 | 17.6 | |

| wbtA::Tn5 | 1.8 × 104 | 0/5 | 7.6 | |

| wzy::Tn5 | 1.2 × 102 | 5/5 | >27 | 1.2 × 104 |

| wzy::Tn5 | 1.2 × 103 | 4/5 | 8, >27 | |

| wzy::Tn5 | 1.2 × 104 | 3/5 | 8, >27 | |

| wzy::Tn5 | 1.2 × 105 | 0/5 | 5.8 | |

| FTT0673plprsAp::Tn5 | 1.4 × 102 | 0/5 | 5.8 | <140 |

| FTT0673plprsAp::Tn5 | 1.4 × 103 | 0/5 | 5 | |

| FTT0673p/prsAp::Tn5 | 1.4 × 104 | 0/5 | 4.8 | |

| FTT0673plprsAp::Tn5 | 1.4 × 105 | 0/5 | 4.2 | |

| FTTOB46::Tn5 | 6.5 × 101 | 5/5 | >27 | 1.5 × 103 |

| FTTOB46::Tn5 | 6.5 × 102 | 4/5 | 25, >27 | |

| FTTOB46::Tn5 | 6.5 × 103 | 0/5 | 17 | |

| FTTOB46::Tn5 | 6.5 × 104 | 0/5 | 12 | |

Discussion

In this work, we identify F. tularensis strains that are defective in capsule and/or LPS biosynthesis by using ELISA to screen a F. tularensis Schu S4 transposon mutant library (7500 individual mutants) (Rasmussen et al., 2014). We identified insertions in six different genes [waaY (2 unique insertions), waaL (3 unique insertions), wzy, wbtA, hemH, and FTT0846] that we subsequently demonstrated were important in capsule biosynthesis (Rasmussen et al., 2014). The waaY and waaL genes were also identified previously in our lab from a TraSH screen in human MDMs (Lindemann et al., 2011). Re-identifying mutants in the waaL and waaY genes provided a strong level of confidence that the other mutant strains identified by ELISA were altered in capsule and/or LPS biogenesis. Since our group has previously identified and characterized the roles of waaY and waaL in capsule and LPS biosynthesis, we have used these strains as controls for the characterization of the new mutants. Consistent with involvement in capsule and LPS biosynthesis, we found that mutation of each of these genes rendered the strains more sensitive to human pooled serum (from 5-fold to 2.4 × 104-fold) than the parent F. tularensis Schu S4. These results are similar to what is observed in other organisms when capsule and/or LPS genes are mutated (Cryz et al., 1984; Rietschel, 1984; Stawski et al., 1990; Dasgupta et al., 1994). Examination of the hemH::Tn5, dnaJ::Tn5, and FTT0673p/prsAp::Tn5 strains revealed that they did not have defects in capsule or LPS that could detected by the assays used, nor did these three mutant strains display attenuated macrophage growth defects or in vivo virulence defects. While these strains were observed to have varying levels of sensitivity to human serum, the amount of serum present in the pooled human serum sensitivity assay is significantly more than in the in vitro cell infection assay. This likely explains why no intramacrophage growth defect was observed with these three strains. Although it is not clear why hemH::Tn5, dnaJ::Tn5, and FTT0673p/prsAp::Tn5 were identified from the ELISA screen, it may have been that the growth conditions employed for the initial ELISA screen maximized differences in expression of capsule and/or LPS production between these strains and the wild type positive control. Besides identifying these three mutant strains of low interest, the ELISA screens identified six mutant strains of high interest that are altered in capsule and/or LPS production, of which four (wzy::Tn5, wbtA:Tn5, manB::Tn5, and FTT0846::Tn5) are characterized further here. Complementation of the defects in these strains was attempted several times with different vector constructs, including with a vector driving expression of the genes with the Pgro promoter. Thus, we conclude that for the FTT0846::Tn5 and wbtA::Tn5 mutant strains that the phenotypes observed are either due to disruption of the gene in which the transposon is inserted or to downstream polar effects.

In examining the annotated functions of wzy, wbtA, manB and FTT0846, it is unclear how the annotated function of the FTT0846 gene product is relevant to LPS and/or capsule biosynthesis. FTT0846 is predicted to encode a deoxyribodipyrimidine photolyase, a class of proteins that are involved in sensing blue light to repair DNA damage. However, it has been postulated that bacterial photolyases can be involved in virulence by regulating the transcription of genes either directly or indirectly (Gaidenko et al., 2006; Purcell et al., 2007; Swartz et al., 2007; Purcell and Crosson, 2008; Cahoon et al., 2011). It is possible that protein produced by FTT0846 is involved in some way in the regulation of LPS core assembly or synthesis, due to the degree of serum sensitivity, a MDM growth defect, and the truncated core observed in the FTT0846 mutant. Future work will be aimed at exploring these possibilities in detail.

For the three other mutants identified from the screens, wbtA::Tn5, wzy::Tn5, and manB::Tn5, there are clear connections to capsule and LPS synthesis. WbtA is a dTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase and has been shown in LVS (Raynaud et al., 2007; Sebastian et al., 2007) and other pathogenic organisms such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bordetella pertussis, and Yersinia enterocolitica to be essential for complete LPS biosynthesis (Creuzenet and Lam, 2001). Specifically, WbtA orthologs are involved in the formation of 6-deoxy sugars (Creuzenet et al., 2000; Creuzenet and Lam, 2001), and the first sugar in the tetrasaccharide repeat of F. tularensis is a 6-deoxy sugar, QuiNAc (Vinogradov et al., 2002). We have presented wbtA mutant data that is consistent with the presumed function of this gene in F. tularensis, as the serum sensitivity of the mutant is increased and a complete LPS core is present, but capsule and LPS-associated O-antigens are not produced as we could not detect these structures in our assays. Interestingly, the glycosylated proteins that we have reported to be present in a waaY mutant strain (Jones et al., 2014), are not present in the wbtA mutant, providing further support for the idea that the wbtA gene product is important for producing complete O-antigen subunits (data not shown).

The Wzy protein is annotated as an O-antigen polymerase and this function was confirmed by Kim et al. (2010) in LVS. The LVS wzy mutant has normal LPS core, but has only one O-antigen tetrasaccharide repeat attached to core (Kim et al., 2010). From our data, the Schu S4 wzy mutant was observed to have a similar phenotype (intact core with only one O-antigen tetrasaccharide repeat). In addition, we observed that this strain lacked O-antigen reactive capsule and displayed an increase in sensitivity to serum.

ManB is a phosphomannose mutase that has been shown in F. novicida to be important for LPS core production (Lai et al., 2010). The Schu S4 manB::Tn5 has a phenotype similar to the F. novicida manB mutant. Experiments to visualize LPS laddering in the Schu S4 manB mutant revealed that it was absent. Surprisingly, we observed that both the FTT0846 and manB mutants produced higher than normal molecular weight capsules albeit in reduced amounts. An unanticipated result from this work has been that mutants with defects in the F. tularensis core sugar assembly pathway do not produce normal LPS O-antigen laddering, yet they still produce capsule which appears larger in size than its wild-type counterpart. An exception to this observation is the F. tularensis waaY::TrgTn mutant strain that does not produce LPS O-antigen laddering or capsule. However, it should be noted that this strain has a polar insertion which also disrupts the downstream gene, waaZ. A goal of the work by our group is to understand this phenomenon in more detail.

When the manB, wzy, wbtA and FTT0846 mutants were used to infect MDMs, no observable differences in intracellular growth were detected at 1 h post–infection or at 16 h post–infection compared to the parent F. tularensis Schu S4. However, by 24 h post–infection there were substantial differences in growth between the mutant strains and the wild type strain, indicating that replication of the mutants in MDMs at later stages of infection is impaired. These phenotypes are similar to those we reported previously for the F. tularensis Schu S4 waaY, waaZ, and waaY O-antigen and capsule mutants (Lindemann et al., 2011). The mutants are even less able to grow within murine macrophages as the manB, wzy, wbtA, and FTT0846 mutants displayed almost no growth in bone marrow derived macrophages during the 24 h infection experiment.

In addition to in vitro experiments, virulence studies were performed by intranasally infecting mice with the manB, wzy, wbtA or FTT0846 mutants, and their respective LD50 values were calculated to be 5.0 × 103-fold, 1.2 × 104-fold, 260-fold, and 1.5 × 103-fold more than the previously published wild type theoretical LD50 of ~1 CFU (Kim et al., 2012). Mice that were infected with manB::Tn5, wbtA::Tn5, wzy::Tn5 or FTT0846::Tn5 displayed ruffled fur (piloerection) within 24–48 h post-infection, suggestive of a gross inflammatory response, similar to what we observed for mice infected with the waaY::TrgTn or waaL::TrgTn strains (Rasmussen et al., 2014). These data are consistent with the in vitro cell growth results in human MDMs and murine BMDMs, in that these mutations impair intracellular growth when compared to Schu S4 over 24 h. In contrast, the hemH::Tn5, dnaJ::Tn5, and FTT0673p/prsAp::Tn5 strains did not have a growth phenotype in macrophages, did not elicit gross inflammatory responses in mice, and did not show an increase in their LD50 values for mice compared to wild type.

As mentioned previously, work has been done with F. tularensis LVS wzy and wbtA mutants. Although our data are in agreement with the O-antigen defects, serum sensitivity, and intramacrophage growth defect reported by other groups with LVS mutants (Raynaud et al., 2007; Sebastian et al., 2007; Thomas et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2010), we observed significantly less diminution of virulence in our i.n. infection experiments using the Schu S4 mutant strains. Sebastian et al. (2007) and Kim et al. (2012) showed that mice infected with either a LVS wbtA or wzy mutant survived a 107 CFU i.n. infection, which is a 20,000-fold increase in the LVS LD50. However, we observed 26-fold and 1200-fold increase in the LD50 values, respectively, for the Schu S4 wbtA and Schu S4 wzy mutants intranasally infected into mice. These data highlight the importance of considering strain background in understanding the role and contribution to virulence of different Francisella factors.

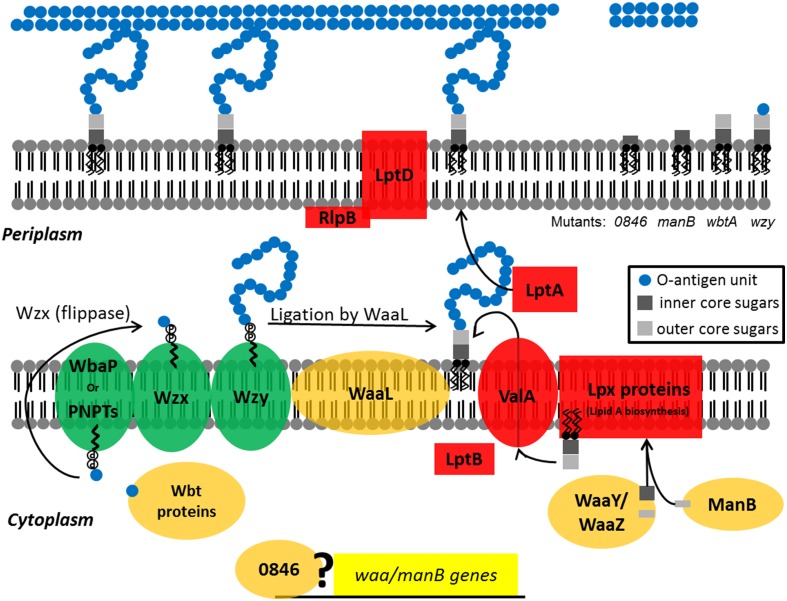

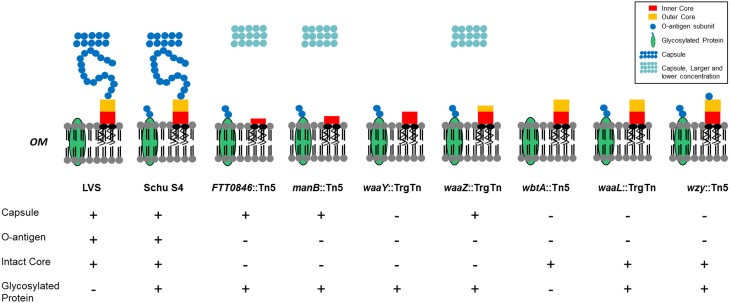

In summary, we present further evidence that the LPS and capsule structures of F. tularensis are essential components of its virulence strategy. Mutations in wzy, wbtA, manB, and FTT0846 affect capsule production, or LPS core and O-antigen structures (Figure 8). In general, mutants with defects in LPS or capsule are sensitive to serum, do not show robust growth after 16 h within human macrophages nor do they grow in murine macrophages, and are attenuated in a murine infection model. In total, our research group has identified seven mutant strains that display varying differences in LPS core structure, LPS-associated O-antigen, capsule, and O-antigen glycosylated proteins in comparison to Schu S4 (Figure 9). These strains are of interest as they grow poorly in macrophages or mouse in an infection model which demonstrates that they are attenuated for virulence. We believe that our data demonstrate that these mutant strains are being detected by the host, which may be a critical first step toward development of a vaccine to an immunologically invisible pathogen. Future studies will focus on what pathway(s) are activated and the degree to which each mutant stimulates a response. The loss of capsule/O-antigen structures allows some level of host recognition of the pathogen, but clearly does not render the strains avirulent. As such, these strains may be reasonable models for genetic dissection of other components of Francisella virulence. In addition, we believe that these strains may be an appropriate place to begin development of a viable, defined vaccine for tularemia.

Figure 8.

Diagram depicting the activities of the F. tularensis WaaY, WaaZ, WaaL, ManB, 0846, Wzy, and WbtA proteins in LPS biosynthesis. LPS is synthesized as two separate components, which are (1) lipid A-core sugars and (2) polymers of O-antigen subunits. O-antigen sugars are synthesized in part by WbtA in the cytoplasm and assembled onto a lipid carrier, the undecaprenol pyrophosphate that is associated with WbaP or PNPT, polyisoprenyl-phosphate hexose-1-phosphate transferase and N-acetylhexosamine-1-phosphate transferase, respectively. The Wzx protein flips the charged lipid carrier, with the assembled O-antigen unit, through the inner membrane from the cytoplasm to the periplasmic space. Repeating O-antigen subunits are polymerized on the lipid carrier by the Wzy protein. The lipid A portion of LPS is synthesized by a number of Lpt and Lpx proteins at the inner leaflet of the inner bacterial membrane. WaaY, WaaZ, and ManB proteins modify or transfer core sugars to the lipid A molecule as they help assemble the core structure of LPS. ValA and LptB transports the lipid A-core sugars to the outer leaflet of the inner membrane where O-antigen subunits are added by the O-antigen ligase, WaaL, and the mature molecule is chaperoned to the outer membrane by LptA and LptD/RlpB (Kim et al., 2010). Possibly the FTT0846 protein is involved in regulation of core sugar genes. F. tularensis mutants that are disrupted in FTT0846 or manB production are depicted with truncated cores whereas the lipid-core sugar structure of the wbtA mutant has a complete core, but no O-antigen. The wzy mutant has a complete core and a single O-antigen tetrasaccharide unit.

Figure 9.

Phenotypes of capsule and/or O-antigen mutants. Properties of the F. tularensis mutants include the presence or absence of capsule, O-antigen, intact core, or O-antigen associated glycosylated proteins (Jones et al., 2014). FTT0846::Tn5, manB::Tn5, and waaZ::TrgTn are shown with a capsule structure that is higher in molecular weight but reduced in concentration when compared to wild type.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for use of the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine Biosafety Level 3 Core Facility as well as the DNA Core and Central Microscopy Research Core for instruction, analysis and provision of reagents. We also thank Dana Ries for her skilled assistance in meeting the regulations of the BSL3. Financial support for this work was provided by NIH grants 2P01 AI044642 (BJ and LA, projects 1 and 3, respectively) and 2U54 AI057160, Research Project 9 of the Midwest Regional Center of Excellence (MRCE) for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Disease Research to BJ and LA. Additional financial support for this work was provided by Predoctoral Training Program in Genetics 5 T32 GM008629 for JF.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2015.00338/abstract

Growth curves of F. tularensis Schu S4 and each of the mutants. Every 2 h samples were taken from each of the cultures and the OD600 was determined.

Intracellular growth of wbtA, wzy, manB, 0846, hemH, dnaJ, waaY, and 0673/prsA intergenic mutants in MDMs. Triplicate wells containing human macrophages were infected for 1 h with unopsonized Schu S4 or mutant bacteria, washed to remove extracellular organisms, and then lysed with 1% saponin at 1, 16, and 24 h post infection to enumerate viable bacteria. Data presented show the average number of bacteria recovered for each strain at 1, 16, and 24 h post-infection. Data are from one experiment representative of three different experiments. (A) Data for the wild type, manB::Tn5, wzy::Tn5, wbtA::Tn5 F. tularensis strains. (B) Data for the wild type, FTT0846::Tn5, hemH::Tn5, FTT0673p/prsAp::Tn5, dnaJ::Tn5, waaY::Tn5 F. tularensis strains.

Intracellular growth of FTT0846, wbtA, wzy, and manB mutants in BMDMs. Murine macrophages were infected for 1 h with unopsonized Schu S4 or mutant bacteria, washed to remove extracellular organisms, and then lysed with 0.5% saponin at 1, 16, and 24 h post-infection to enumerate viable bacteria. Data presented shows the average number of bacteria recovered for each strain at 1, 16, and 24 h post-infection. Data are from one experiment that is representative of three experiments.

Survival curves of BALB/c mice infected with F. tularensis Schu S4 wild type or mutant strains carrying transposon insertions in dnaJ, hemH, manB, wzy, wbtA, FTT0846 and between FTT0673 and the prsA gene. Mice were infected with 23 cfu of F. tularensis Schu S4 as a positive control for virulence. Four groups of mice were infected for each of the indicated F. tularensis mutant strain at four different doses that increased 10-fold. Mice were examined daily and the number of mice that were alive each day from each group was recorded and is shown on the graph. Mice infected with strains with mutations that did not significantly alter virulence were typically dead at day 5 or day 6. Mice infected with attenuated strains were followed up to 40 days post-infection depending upon signs of illness such as piloerection, hunching and lethargy. Some infected groups of mice became ill at significantly delayed time points and those groups of mice were followed for extended periods of time. Ultimately all mice were sacrificed according to protocol and disposed of in accordance with BSL-3 regulations.

References

- Allen L. A., Aderem A. (1996). Molecular definition of distinct cytoskeletal structures involved in complement- and Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 184, 627–637. 10.1084/jem.184.2.627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apicella M. A., Post D. M., Fowler A. C., Jones B. D., Rasmussen J. A., Hunt J. R., et al. (2010). Identification, characterization and immunogenicity of an O-antigen capsular polysaccharide of Francisella tularensis. PLoS ONE 5:e11060. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker J. R., Klose K. E. (2007). Molecular and genetic basis of pathogenesis in Francisella tularensis. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1105, 138–159. 10.1196/annals.1409.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan B. W., McLendon M. K., Jones B. D. (2008). Identification of differentially regulated Francisella tularensis genes by use of a newly developed Tn5-based transposon delivery system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 2637–2645. 10.1128/AEM.02882-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahoon L. A., Stohl E. A., Seifert H. S. (2011). The Neisseria gonorrhoeae photolyase orthologue phrB is required for proper DNA supercoiling but does not function in photo-reactivation. Mol. Microbiol. 79, 729–742. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07481.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho C. L., Lopes de Carvalho I., Ze-Ze L., Nuncio M. S., Duarte E. L. (2014). Tularaemia: a challenging zoonosis. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 37, 85–96. 10.1016/j.cimid.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case E. D., Chong A., Wehrly T. D., Hansen B., Child R., Hwang S., et al. (2013). The Francisella O-antigen mediates survival in the macrophage cytosol via autophagy avoidance. Cell. Microbiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Tularemia - United States, 2001-2010. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 62, 963–966. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay C. D., Soni S., Gunn J. S., Schlesinger L. S. (2008). Evasion of complement-mediated lysis and complement C3 deposition are regulated by Francisella tularensis lipopolysaccharide O antigen. J. Immunol. 181, 5568–5578. 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comstock L. E., Kasper D. L. (2006). Bacterial glycans: key mediators of diverse host immune responses. Cell 126, 847–850. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creuzenet C., Lam J. S. (2001). Topological and functional characterization of WbpM, an inner membrane UDP-GlcNAc C6 dehydratase essential for lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 41, 1295–1310. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02589.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creuzenet C., Schur M. J., Li J., Wakarchuk W. W., Lam J. S. (2000). FlaA1, a new bifunctional UDP-GlcNAc C6 Dehydratase/ C4 reductase from Helicobacter pylori. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 34873–34880. 10.1074/jbc.M006369200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryz S. J., Jr., Pitt T. L., Furer E., Germanier R. (1984). Role of lipopolysaccharide in virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 44, 508–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta T., de Kievit T. R., Masoud H., Altman E., Richards J. C., Sadovskaya I., et al. (1994). Characterization of lipopolysaccharide-deficient mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa derived from serotypes O3, O5, and O6. Infect. Immun. 62, 809–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin O. M., Duplantis B. N., Ludu J. S., Hare R. F., Nix E. B., Schmerk C. L., et al. (2011). The biochemical properties of the Francisella pathogenicity island (FPI)-encoded proteins IglA, IglB, IglC, PdpB and DotU suggest roles in type VI secretion. Microbiology 157, 3483–3491. 10.1099/mic.0.052308-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaidenko T. A., Kim T. J., Weigel A. L., Brody M. S., Price C. W. (2006). The blue-light receptor YtvA acts in the environmental stress signaling pathway of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 188, 6387–6395. 10.1128/JB.00691-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho T. D., Waldor M. K. (2007). Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 gal mutants are sensitive to bacteriophage P1 and defective in intestinal colonization. Infect. Immun. 75, 1661–1666. 10.1128/IAI.01342-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iredell J. R., Stroeher U. H., Ward H. M., Manning P. A. (1998). Lipopolysaccharide O-antigen expression and the effect of its absence on virulence in rfb mutants of Vibrio cholerae O1. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 20, 45–54. 10.1016/S0928-8244(97)00106-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B. D., Faron M., Rasmussen J. A., Fletcher J. R. (2014). Uncovering the components of the Francisella tularensis virulence stealth strategy. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 4:32. 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T. H., Pinkham J. T., Heninger S. J., Chalabaev S., Kasper D. L. (2012). Genetic modification of the O-polysaccharide of Francisella tularensis results in an avirulent live attenuated vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 205, 1056–1065. 10.1093/infdis/jir620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T. H., Sebastian S., Pinkham J. T., Ross R. A., Blalock L. T., Kasper D. L. (2010). Characterization of the O-antigen polymerase (Wzy) of Francisella tularensis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 27839–27849. 10.1074/jbc.M110.143859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai X. H., Shirley R. L., Crosa L., Kanistanon D., Tempel R., Ernst R. K., et al. (2010). Mutations of Francisella novicida that alter the mechanism of its phagocytosis by murine macrophages. PLoS ONE 5:e11857. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Ryder C., Mandal M., Ahmed F., Azadi P., Snyder D. S., et al. (2007). Attenuation and protective efficacy of an O-antigen-deficient mutant of Francisella tularensis LVS. Microbiology 153, 3141–3153. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/006460-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann S. R., Peng K., Long M. E., Hunt J. R., Apicella M. A., Monack D. M., et al. (2011). Francisella tularensis Schu S4 O-antigen and capsule biosynthesis gene mutants induce early cell death in human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 79, 581–594. 10.1128/IAI.00863-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier T. M., Casey M. S., Becker R. H., Dorsey C. W., Glass E. M., Maltsev N., et al. (2007). Identification of Francisella tularensis Himar1-based transposon mutants defective for replication in macrophages. Infect. Immun. 75, 5376–5389. 10.1128/IAI.00238-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier T. M., Havig A., Casey M., Nano F. E., Frank D. W., Zahrt T. C. (2004). Construction and characterization of a highly efficient Francisella shuttle plasmid. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 7511–7519. 10.1128/AEM.70.12.7511-7519.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLendon M. K., Apicella M. A., Allen L. A. (2006). Francisella tularensis: taxonomy, genetics, and Immunopathogenesis of a potential agent of biowarfare. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 60, 167–185. 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyston P. C. (2008). Francisella tularensis: unravelling the secrets of an intracellular pathogen. J. Med. Microbiol. 57, 921–930. 10.1099/jmm.0.2008/000653-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyston P. C., Sjostedt A., Titball R. W. (2004). Tularaemia: bioterrorism defence renews interest in Francisella tularensis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 967–978. 10.1038/nrmicro1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post D. M., Yu L., Krasity B. C., Choudhury B., Mandel M. J., Brennan C. A., et al. (2012). O-antigen and core carbohydrate of Vibrio fischeri lipopolysaccharide: composition and analysis of their role in Euprymna scolopes light organ colonization. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 8515–8530. 10.1074/jbc.M111.324012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior J. L., Prior R. G., Hitchen P. G., Diaper H., Griffin K. F., Morris H. R., et al. (2003). Characterization of the O antigen gene cluster and structural analysis of the O antigen of Francisella tularensis subsp. tularensis. J. Med. Microbiol. 52, 845–851. 10.1099/jmm.0.05184-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell E. B., Crosson S. (2008). Photoregulation in prokaryotes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11, 168–178. 10.1016/j.mib.2008.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell E. B., Siegal-Gaskins D., Rawling D. C., Fiebig A., Crosson S. (2007). A photosensory two-component system regulates bacterial cell attachment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 18241–18246. 10.1073/pnas.0705887104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen J. A., Post D. M., Gibson B. W., Lindemann S. R., Apicella M. A., Meyerholz D. K., et al. (2014). Francisella tularensis Schu S4 LPS core sugar and O-antigen mutants are attenuated in a mouse model of Tularemia. Infect. Immun. 82, 1523–1539. 10.1128/IAI.01640-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raynaud C., Meibom K. L., Lety M. A., Dubail I., Candela T., Frapy E., et al. (2007). Role of the wbt locus of Francisella tularensis in lipopolysaccharide O-antigen biogenesis and pathogenicity. Infect. Immun. 75, 536–541. 10.1128/IAI.01429-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed L. J., Muench H. (1938). A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am. J. Epidemiol. 27, 493–497. 15955576 [Google Scholar]

- Rietschel E. T. (1984). Chemistry of Endotoxin. New York, NY: Elsevier; Sole distributor for the USA and Canada, Elsevier Science Pub. Co., Amsterdam; New York. [Google Scholar]

- Sandstrom G., Lofgren S., Tarnvik A. (1988). A capsule-deficient mutant of Francisella tularensis LVS exhibits enhanced sensitivity to killing by serum but diminished sensitivity to killing by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Infect. Immun. 56, 1194–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saslaw S., Eigelsbach H. T., Prior J. A., Wilson H. E., Carhart S. (1961). Tularemia vaccine study. II. Respiratory challenge. Arch. Intern. Med. 107, 702–714. 10.1001/archinte.1961.03620050068007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulert G. S., Allen L. A. (2006). Differential infection of mononuclear phagocytes by Francisella tularensis: role of the macrophage mannose receptor. J. Leukoc. Biol. 80, 563–571. 10.1189/jlb.0306219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian S., Dillon S. T., Lynch J. G., Blalock L. T., Balon E., Lee K. T., et al. (2007). A defined O-antigen polysaccharide mutant of Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain has attenuated virulence while retaining its protective capacity. Infect. Immun. 75, 2591–2602. 10.1128/IAI.01789-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng H., Lim J. Y., Watkins M. K., Minnich S. A., Hovde C. J. (2008). Characterization of an Escherichia coli O157:H7 O-antigen deletion mutant and effect of the deletion on bacterial persistence in the mouse intestine and colonization at the bovine terminal rectal mucosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 5015–5022. 10.1128/AEM.00743-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjostedt A. (2007). Tularemia: history, epidemiology, pathogen physiology, and clinical manifestations. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1105, 1–29. 10.1196/annals.1409.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stawski G., Nielsen L., Orskov F., Orskov I. (1990). Serum sensitivity of a diversity of Escherichia coli antigenic reference strains. Correlation with an LPS variation phenomenon. APMIS 98, 828–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su J., Yang J., Zhao D., Kawula T. H., Banas J. A., Zhang J. R. (2007). Genome-wide identification of Francisella tularensis virulence determinants. Infect. Immun. 75, 3089–3101. 10.1128/IAI.01865-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz T. E., Tseng T. S., Frederickson M. A., Paris G., Comerci D. J., Rajashekara G., et al. (2007). Blue-light-activated histidine kinases: two-component sensors in bacteria. Science 317, 1090–1093. 10.1126/science.1144306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarnvik A., Berglund L. (2003). Tularaemia. Eur. Respir. J. 21, 361–373. 10.1183/09031936.03.00088903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R. M., Titball R. W., Oyston P. C., Griffin K., Waters E., Hitchen P. G., et al. (2007). The immunologically distinct O antigens from Francisella tularensis subspecies tularensis and Francisella novicida are both virulence determinants and protective antigens. Infect. Immun. 75, 371–378. 10.1128/IAI.01241-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradov E., Perry M. B., Conlan J. W. (2002). Structural analysis of Francisella tularensis lipopolysaccharide. Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 6112–6118. 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03321.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Shi X., Leymarie N., Madico G., Sharon J., Costello C. E., et al. (2011). A typical preparation of Francisella tularensis O-antigen yields a mixture of three types of saccharides. Biochemistry 50, 10941–10950. 10.1021/bi201450v [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrly T. D., Chong A., Virtaneva K., Sturdevant D. E., Child R., Edwards J. A., et al. (2009). Intracellular biology and virulence determinants of Francisella tularensis revealed by transcriptional profiling inside macrophages. Cell. Microbiol. 11, 1128–1150. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01316.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss D. S., Brotcke A., Henry T., Margolis J. J., Chan K., Monack D. M. (2007). In vivo negative selection screen identifies genes required for Francisella virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 6037–6042. 10.1073/pnas.0609675104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield C. (2006). Biosynthesis and assembly of capsular polysaccharides in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75, 39–68. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zogaj X., Klose K. E. (2010). Genetic manipulation of Francisella tularensis. Front. Microbiol. 1:142. 10.3389/fmicb.2010.00142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Growth curves of F. tularensis Schu S4 and each of the mutants. Every 2 h samples were taken from each of the cultures and the OD600 was determined.

Intracellular growth of wbtA, wzy, manB, 0846, hemH, dnaJ, waaY, and 0673/prsA intergenic mutants in MDMs. Triplicate wells containing human macrophages were infected for 1 h with unopsonized Schu S4 or mutant bacteria, washed to remove extracellular organisms, and then lysed with 1% saponin at 1, 16, and 24 h post infection to enumerate viable bacteria. Data presented show the average number of bacteria recovered for each strain at 1, 16, and 24 h post-infection. Data are from one experiment representative of three different experiments. (A) Data for the wild type, manB::Tn5, wzy::Tn5, wbtA::Tn5 F. tularensis strains. (B) Data for the wild type, FTT0846::Tn5, hemH::Tn5, FTT0673p/prsAp::Tn5, dnaJ::Tn5, waaY::Tn5 F. tularensis strains.

Intracellular growth of FTT0846, wbtA, wzy, and manB mutants in BMDMs. Murine macrophages were infected for 1 h with unopsonized Schu S4 or mutant bacteria, washed to remove extracellular organisms, and then lysed with 0.5% saponin at 1, 16, and 24 h post-infection to enumerate viable bacteria. Data presented shows the average number of bacteria recovered for each strain at 1, 16, and 24 h post-infection. Data are from one experiment that is representative of three experiments.

Survival curves of BALB/c mice infected with F. tularensis Schu S4 wild type or mutant strains carrying transposon insertions in dnaJ, hemH, manB, wzy, wbtA, FTT0846 and between FTT0673 and the prsA gene. Mice were infected with 23 cfu of F. tularensis Schu S4 as a positive control for virulence. Four groups of mice were infected for each of the indicated F. tularensis mutant strain at four different doses that increased 10-fold. Mice were examined daily and the number of mice that were alive each day from each group was recorded and is shown on the graph. Mice infected with strains with mutations that did not significantly alter virulence were typically dead at day 5 or day 6. Mice infected with attenuated strains were followed up to 40 days post-infection depending upon signs of illness such as piloerection, hunching and lethargy. Some infected groups of mice became ill at significantly delayed time points and those groups of mice were followed for extended periods of time. Ultimately all mice were sacrificed according to protocol and disposed of in accordance with BSL-3 regulations.