Abstract

Many current mobile health applications (“apps”) and most previous research have been directed at management of chronic illnesses. However, little is known about patient preferences and design considerations for apps intended to help in a post-acute setting. Our team is developing an mHealth platform to engage patients in wound tracking to identify and manage surgical site infections (SSI) after hospital discharge. Post-discharge SSIs are a major source of morbidity and expense, and occur at a critical care transition when patients are physically and emotionally stressed. Through interviews with surgical patients who experienced SSI, we derived design considerations for such a post-acute care app. Key design qualities include: meeting basic accessibility, usability and security needs; encouraging patient-centeredness; facilitating better, more predictable communication; and supporting personalized management by providers. We illustrate our application of these guiding design considerations and propose a new framework for mHealth design based on illness duration and intensity.

Introduction

Although much mHealth research supports managing chronic illness, relatively little is known about how mHealth could apply to acute conditions. New incentives (e.g., Accountable Care Organizations, bundled payments) will lead hospitals and providers to optimize care across the whole care spectrum, including areas such as post-acute care (i.e., happening after acute hospitalization). Post-acute care mHealth could facilitate care coordination by filling in gaps that occur during this significant transition of care. This coordination could prevent costly readmissions as well as improve patients’ experiences during this often stressful time.1

Improving care coordination among surgical patients after discharge is of critical importance. These patients are at high risk for surgical site infections (SSI), most of which occur after discharge.2,3 SSIs are the leading cause of readmission among surgical patients, which occurs in up to half of patients who experience SSI.2 In our previous work we found that patients were ill equipped to recognize and manage wound complications, and faced many barriers to communicating with their providers after developing a concern. Patients found the concept of an mHealth wound tracking and communication tool highly acceptable and believed it could help address many gaps in the current system.4

In this paper, we extend our previous work by describing design considerations for post-acute care mHealth apps, derived from interviews with surgical patients who experienced wound complications while at home. Many of these patients had extreme experiences, both in terms of their physical and emotional state (e.g., anxiety, disorientation) and their interactions with the health care system (e.g., late night calls to triage nurses, emergency department visits, readmissions). These experiences allowed us to explore a breadth of the post-acute mHealth design space, although not all issues we identified will likely apply to every post-acute care mHealth app. In our discussion, we describe several core themes that emerged related to communication and management that could be applicable to a wider range of acute care apps. We then illustrate how we applied these design considerations to an mHealth app we are developing to engage surgical patients in post-discharge wound tracking. Finally, we introduce a new framework for mHealth design based on illness duration and intensity.

Background

The design space around mHealth for management of chronic conditions is relatively mature, especially for conditions such as cancer5,6 or diabetes7,8. It is unclear whether design considerations for chronic mHealth apps apply as well in a post-acute setting. Apps for management of chronic conditions are characterized by achieving symptom control and long-term behavioral change. In contrast, the purpose of a post-acute care app might be to help avoid escalation around a single, limited duration episode of treatment while a patient is returning to a usual health state.

Some design considerations likely apply across a wide range of mHealth settings. For example, Klasnja et al9 found that the ability for cancer patients to capture and access a variety of care-related information while on the go, in a single application, helped them manage their care and feel more in control of their information and health. Since managing information is a key task for patients in any setting, enabling the organized storage of health information is likely to be a universal mHealth theme. Arsand et al10 found that diabetes patients preferred to have some reward (e.g. education or feedback) at the time of data entry to provide a built-in motivation for use. This finding relates to a broader theme that, in order to continue using apps, patients must find them to have utility—not just in a theoretical sense, but also in an immediate, concrete sense. Liu et al11 found that parents wanted to communicate with providers in different ways to suit their needs, both synchronously (e.g. telephone) or asynchronously (e.g. email). Communication with providers can be critical across a range of chronic and acute conditions, and supportive mHealth applications should facilitate communication using means that are both efficient and acceptable to patients. Kientz et al12 suggest that the act of tracking health measures (e.g. infant development) has the potential to increase anxiety over trends that appear abnormal. Apps that capture patient data will have to carefully consider how to reflect that data back to patients, including whether and how to provide interpretation of that data.

Other design considerations for chronic mHealth apps might be less applicable or introduce new challenges in an acute context, ranging from privacy and self-reflection to automated feedback and engaging social networks. For example, Patel et al5 identified giving breast cancer patients ownership over data (e.g. controlling what data is shared, capturing custom fields) as important to promote engagement in care and capture of sensitive data. Although patients should always have control over what information is shared with others, acute care providers may be concerned about patients sharing too much data that cannot be efficiently reviewed. Mamykina et al7 identified promoting self-reflection as a primary design goal to aid in self-management for people with diabetes. Self-reflection is a critical element in the management of many chronic illnesses that rely on patients to make lasting behavioral changes. However, the importance of self-reflection is unclear given the short time horizons, cognitive impairments (e.g., due to pain medication), and limited control that patients often have over their care outcomes that might be common in the post-acute setting. In addition to self-reflection, Harris et al8 identified automated, programmed responses as a key design requirement for diabetes self-management. Automated responses may support self-reflection and have the benefit of giving immediate feedback and gratification to patients without burdening a clinician, however more urgent or complex assessments associated with acute concerns might not be reliably made without human involvement. Finally, much work has been done using mHealth to help patients engage social networks and online communities for support in their care (e.g., Liu et al11 in the parenting of high-risk infants). However, the utility of online communities is unclear over short durations and highly individualized recovery periods following hospital discharge. In addition, unlike with chronic conditions, acute conditions tend not to have dedicated online communities.

Though the examples above are not exhaustive, and many design considerations for chronic mHealth apps likely apply to acute apps as well, we suggest that the requirements and user experience in acute and chronic settings are sufficiently different to warrant further research. In this paper, we report on our work to explore a design space for apps which improve communication and decision support in the post-acute care setting.

Methods

We conducted semi-structured interviews with patients who experienced surgical wound complications after hospital discharge. The study was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

Participants and setting

We interviewed patients who had post-discharge wound complications after undergoing abdominal surgery at one of two Seattle hospitals: an academic medical center or a county hospital/regional trauma center. We identified English-speaking, adult patients using two different approaches: through clinic nurses at follow-up visits or through flyers placed in surgery clinics.

Data collection

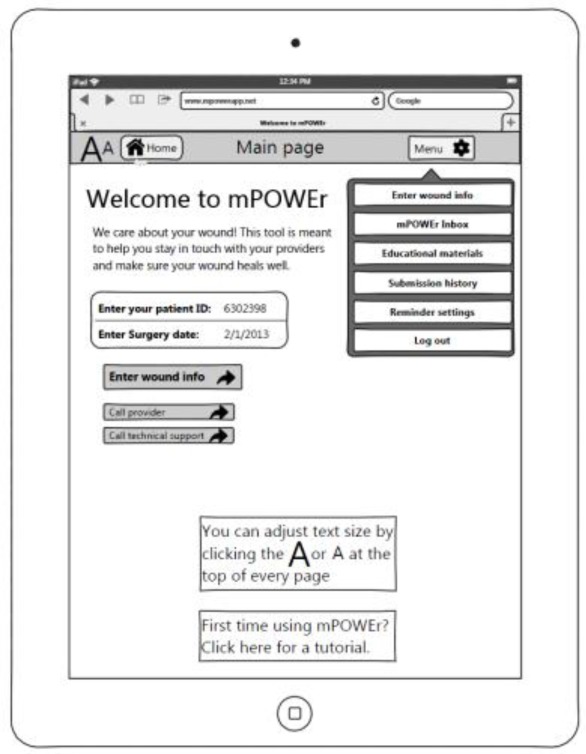

We conducted one-on-one interviews lasting 60–90 minutes in a private setting near the clinics. We began by using the critical incident technique to guide participants in recounting their complication experience.13 Then, grounded in their experience, we used scenarios to provide context to allow participants to walk through paper wireframe mockups (Figure 1) of an mHealth wound tracking application (e.g. “Imagine you are very concerned about your wound. You just clicked ‘submit’ to send your symptom data. What should happen now?”). We showed mockups of multiple versions of potential features such as symptom tracking, wound photography, secure communication, and informational content. Prior to showing mockups of each feature, the interviewer paused to ask the participant to describe how a particular feature might work; only then did the interviewer use the paper mockups to stimulate further discussion. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. We collected data until thematic saturation was achieved.14 We used written surveys to capture demographics and technology experience.

Figure 1:

Paper mockups used during participant interviews to stimulate discussion.

Data analysis

We collectively developed a codebook with two team members coding all the interviews using Atlas.ti (Atlas.ti v7, ATLAS.ti GmbH) while other team members spot-coded interviews to inform the codebook and check reliability. The whole team met periodically to resolve coding discrepancies. Cohen’s Kappa between the two primary coders during early and late coding was 0.51 and 0.71, respectively, reflecting moderate to substantial inter-coder reliability.

Results

We interviewed 13 patients ranging from age 21 to 71 (mean 45), of whom 9 were female and 9 were white. Five were college graduates, 6 had some college, 1 graduated from high school and 1 had less than high school education. They self-rated their experience with computers as “some” (n=3), “intermediate” (n=4), “very” (n=4), or “expert” (n=2). Twelve used the internet at least occasionally and 8 owned a smartphone. Patients underwent major abdominal surgery, generally colorectal or ventral hernia repair, and struggled with complications for weeks or months after discharge. Five had one or more emergency department visits or hospital readmissions related to SSI.

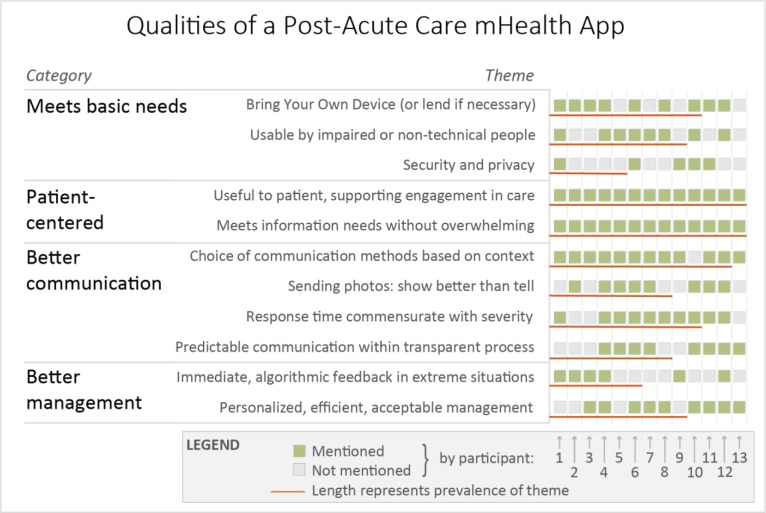

From patient interviews, we identified 11 themes that we organized into 4 categories that describe qualities of a post-acute care mHealth application (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Each green square represents a participant who mentioned the theme during interviews. Length of red lines represents theme prevalence. Themes are organized into 4 major categories, visible on the left side of the figure.

Meets basic needs

One category of design qualities for a supportive mHealth tool expressed by participants revolved around meeting basic needs through accessibility of your own device, usability by impaired or non-technical people, and security to preserve privacy. P#’s following quotes are attributions to that particular participant.

Bring Your Own Device (or lend if necessary)

Participants were concerned about an app being inaccessible on their preferred device or had concern for others who lacked access to a smartphone or computer. Several participants suggested that hospitals could loan patients devices.

What about people that don’t have smart phones? Will you have this on a regular online website with it too? Because my phone is like ten years old. P12

I think it’s a good idea if you have someone who’s technology proficient in something like that. Some of the patients may not even have computer or computer access. But I think for me personally, I mean, because I’m used to computers, I think it’s a great idea. P4

Usability by impaired or non-technical people

Participants had concern for technologically inexperienced users, and did not want to be overwhelmed with information or too many pages/functions. Participants mentioned the challenge of using an app while on pain medication, and wanted simple wording, obvious alerts and clear navigation.

But if you don’t have [a smartphone] you might not know how to work it, so then you’re going to have to get into who’s smarter, the phone or you? You know, somebody’s going to have to show you how to even operate the thing. P10

But it would make a complex website or doing something complex, it would require you to remember several steps. I think [navigating a complex website under influence of drugs] would make it very difficult for a lot of people. P12

Security and Privacy

While this was among the least prevalent themes, participants were most concerned about collection and transmission of particularly sensitive information such as photos of the groin area. Participants expressed concern that transmissions should be secure and go to the right recipients.

Some people might not want to [send pictures of private areas]. Your older generation. P6

As long as [the submissions] made it from point A to point B, it would be good. They didn’t get lost in sending… to a bakery or something. P11

Patient-centered

A second major category of design qualities pointed to the importance of patient-centeredness: being genuinely useful to the patient to support engagement in their own care and meeting their individualized information needs without overwhelming them.

Useful to patient, supporting engagement in care

All participants voiced that the app should be genuinely useful to the patient—having an obvious benefit and not feeling like a burden on them. They felt that the app should allow patients to be engaged in and make decisions about their care, especially about how often and by what means they discuss their concerns with providers. Several expressed that the app should have a “personal feel” that gives the feeling that “we want to take care of you” (P1). Participants also felt that the app should connect them with a provider familiar with their history and with whom they already have a relationship/rapport.

The biggest thing is for me to feel like this is useful, because it’s being sent to my doctor. This is a way of communication to my doctor, not just a survey I’m taking, you know what I mean? P5

[The ability to view past photos/history would be useful] because then you could see – oh, this is what this looked like 3 days ago and this is what it looks like now. This looks really different. P7

Meets information needs without overwhelming

Participants generally did not feel that their information needs were met well during their hospital discharge experience. Every participant saw an opportunity for the app to make up for this deficit by providing a personalized, succinct recap of their discharge instructions. They emphasized that they did not want to be overwhelmed, asking for just the highlights with links to more resources if needed. Most participants wanted to have information on procedures they themselves would be expected to perform after discharge (e.g. how to clean and pack wound) and how to identify problems (e.g. infection). Participants preferred concrete examples through a variety of media over reams of pages (e.g. photos of infected vs normal wound, step-by-step instructions/video of wound care procedure). Several participants were also interested in receiving information about how to optimize their healing (e.g. dietary advice). Participants wanted the app itself to be well-documented with help/tutorials.

Like if you forget how to clean and pack your wound or whatever, or if your wound looks like this, then [it’s infected] - or if your wound looks like this, then [it’s not infected]. That might be helpful… Mainly just in terms of if this happens, don’t freak out. If this happens, do freak out. P7

So if you’re going to do a presentation for somebody coming out of the hospital, you should only have the highlights… [have a] mouseover if they [want] a big explanation. P1

Better communication

A third major category of design qualities pointed to the potential for enhanced communication, whether through more choice of communication methods appropriate to context (e.g., secure text for non-urgent matters), the ability to send photographs, rapid provider response when necessary, and patient control over and transparency about timing and method of provider contact.

Choice of communication methods based on context

Participants wanted to be able to choose the means of communication with their provider. Context was important—if they were very concerned about an issue, participants preferred a telephone call. When participants were not very concerned (e.g. routine check-ins, non-time sensitive care questions), many preferred text or email as it was more convenient for them and less interruptive to their providers than phone calls. Two participants suggested that real-time video conferencing should be incorporated into the app.

[The app should have] an option of how would you best like to be communicated with… Would you like it email, text message, phone call and they can select that, and it can go right in with the message. … Because [grandmother] would pick a phone call, [mother] and I would pick a text message. P6

It depends on the situation, but I don’t know, for me personally, I like to do stuff through email … Unless it’s like super urgent, so obviously phone call is the best way to get [urgent] communication. But I think for this type of stuff, I wouldn’t mind email, as long as I knew that the doctor’s looking at it throughout the day. P4

Sending photos: show is better than tell

Participants were very interested in sending photos to providers. They wanted their provider to really see that status of their wound rather than try to explain solely over the phone. They thought that this additional visual information would facilitate triage and management, be less subjective than patient-assessed symptoms (e.g. amount of redness), and help show trends across time through serial photography. Participants recognized that photos were necessary but not sufficient–some patient-assessed symptoms would be valuable to report (e.g. heat, pain).

I have a smart phone so I used that to take the picture. I thought that was very good to be able to send them an actual picture of what was happening so that way, you know, a little more hands on than “okay - this is… ” - trying to describe it over the phone… The nurse commented about how good that was too to have a picture to look at. P6

So if you had it where you could take a picture of it… [the provider] might have said “oh boy, you need to go into the hospital” [or] they could say “hey – no, it’s doing what it’s supposed to do, just let it be.” P10

Response time commensurate with severity

Participants wanted faster response times based on their level of concern and/or the apparent severity of their wound problem—in other words, the app should facilitate triage to enable provider feedback faster based on urgency. Many participants made comparisons to the main alternative to using the app—a phone call—saying that response times should be comparable (e.g. call back within 30 minutes). Participants voiced worries that waiting for even an hour might be too long for an acute concern and that if responses are too delayed, their condition could deteriorate. Of those who specified how quickly they would expect a response, 2 said under 30 minutes, 1 said within an hour, 2 said within 4 hours, and 4 said within 24 hours. Participants were willing to wait longer for a response if they had confidence in the system–that their responses were being monitored regularly and not falling into a “black hole” (P4).

I think that if it would have been really hurting, I would want a quicker response time for it. So I think based on the level of pain that somebody was having as to what the response - or felt they were having, the response time back would be quicker. P6

When you pick up the phone you’re getting a response. If you’re using a tool and you’re not getting anything back, then there’s no reason to use it because the whole reason is to get communications. P1

Predictable communication within a transparent process

Participants wanted a definite timeframe for a provider response, i.e. a shared expectation between patients and providers. Generally they expected the provider to set this parameter but several wanted to select a time and/or be able to “escalate” to request a faster response. Participants wanted the process to be transparent – to know when their data was received, viewed, and acted upon. They also wanted to be able to set the contact method so they would know what to expect (e.g. wouldn’t have to wait around at their computer in case of email response).

Some type of timeframe. So it’s not just kind of like sitting out there and you just submit it to a black hole, you know, when someone’s going to get back to you. P4

[After clicking submit, the app should say] ‘please watch your email during the next three hours or something for a response’. Or whatever you guys decide the response time should be. And/or choose a phone call back. In other words, to know on here before I log off what I can expect next… P12

Better management

A final major category of design qualities pointed to the potential for better, faster, more personalized and more acceptable (to the patient) management. Participants saw many potential benefits including earlier identification and treatment of problems, and the possibility of more efficient care through reduction in unnecessary visits.

Immediate, algorithmic feedback in extreme situations

Participants found the idea of algorithmic (i.e. immediate, app-generated) feedback most acceptable at the extremes—i.e. their situation appears very good or very bad. In less clear-cut cases, most favored the judgment of their health care provider. Participants thought algorithmic feedback was good if it was based on existing practices (e.g. algorithms used by triage nurses). Participants noted that algorithms could benefit both the patient (e.g. advise to go to emergency department immediately if reporting chest pain) and the provider (e.g. flag most concerning patients to review quickly). In general, most participants did not fully trust the computer to make unsupervised management decisions, noting that the quality of the patient input is critical; misjudgments about symptoms could lead patients to unnecessary emergency room visits.

I think yeah, that’s all right for the extremes. But I still would feel more comfortable with the doctor responding. P4

It’s the same judgment that you would get if you called a nurse, well, it’s probably the same thing you were told outright – if you see this, call the nurse or come into the emergency room. So if the app is just reinforcing that, it seems perfectly natural. P3

Personalized, efficient, acceptable (to the patient) management

Almost universally, patients saw the potential for an app to facilitate better triage. For example, the app could help the patient answer the anxiety-ridden question, “What do I do? Come in or stay home?” (P8). Through better triaging, patients expected a variety of potential benefits. If they were healing normally, for example, the app could save time and unnecessary clinic/emergency room visits, which is especially important for distant patients, as well as alleviate stress and provide reassurance. If their wound was not healing normally, the app could facilitate earlier problem identification and quicker/easier re-admission than the current management process patients experienced. Patients liked the idea of giving their provider more data (especially photos) to track their progress, and would be more willing to accept providers’ management decisions based on that more complete, standardized, and personalized data. For example, they would be more willing to go to ER if advised to do so.

That’s pretty much what the triage nurse tells you anyway. You have to come in [to the emergency room]. But if you have a picture of it, and it’s nothing, then that would make it so that you wouldn’t have to go in necessarily… It would be more advantageous and you wouldn’t have to sit there for five hours (laughs) in the ER. P10

But it would have been really helpful, especially the first time that it started getting infected, I could have sent them a picture or whatever and then if a day later - because it did, it got a lot worse. It was itching, it was bleeding and stuff - then I could have sent another picture and said it’s a lot worse and they could have seen right then you need to come in now. Instead of waiting until it got really bad. P7

Discussion

Our findings illustrate the large potential benefits that patients see in post-acute care mHealth apps. Indeed, such apps are probably inevitable, but the key question is: will they be embraced by patients? Due to the hectic and stressful time during care transitions after acute illness, it is critical that apps be immediately usable and obviously useful to patients or they will not be used. Both patients and clinicians will lose out if patients reject this powerful method to facilitate data gathering and communication in favor of the highly usable yet limiting alternative—the telephone. However, it is challenging to design for short-term post-acute episodes for a number of reasons. First, there are a large number of possible use cases, and acute problems do not necessarily follow a predictable disease course. Second, related to user-centered design, it is challenging to engage patients in the moment, while they are actually sick, and due to the short-term nature of acute conditions, patients may lack the expertise about managing their condition that patients with chronic illness may have. Finally, it is unclear whether prior work on mHealth for chronic illness management is applicable in a post-acute context.

Although many themes voiced by our participants were common across mHealth, several appeared novel, reflecting the specific needs of patients in a particular post-acute setting (Table 1).

Table 1:

Common themes across mHealth vs new themes for post-acute care mHealth. Key themes identified from patient interviews have been categorized based on whether they are already known in the mHealth literature or appear novel to a post-acute setting.

| Support for known themes across mHealth | New themes specific to post-acute setting |

| • Bring your own device/loans • Security and privacy • Useful to the patient, supporting engagement • Algorithmic feedback when appropriate • Choice of communication methods based on context • Photos (or other sensor-based data): show is better than tell • Meeting information needs without overwhelming |

• Response time commensurate with severity • Predictable patient-provider communication within a transparent process • Personalized, more efficient, more acceptable treatment plan based on patient-reported data • Usability while in a cognitively or physically impaired state |

The most important insights about patient expectations for acute care mHealth apps relate to patient-provider communication and resulting management of care concerns. This prioritization likely reflects the challenges and frustrations participants faced when managing their post-discharge complications. For example, after developing a wound concern, participants described a lack of control over their situation. Related to communication, they could not easily or quickly reach a familiar provider. Related to management, they often felt unnecessarily directed to the emergency department as the default option. Through an mHealth application, patients wanted to be empowered to choose how and when they would be contacted, and wanted to be satisfied that the provider managing their care made a personalized recommendation based on all available information (e.g. through review of serial symptom logs and wound photos). Because issues of patient-provider communication and management are essential to addressing many acute concern, future work could explore the generalizability of these themes across a variety of acute and post-acute conditions.

Although our findings are limited to patient views, one of the key differentiating elements of acute mHealth is the relative importance of other stakeholders, most notably providers. Acute mHealth apps must be designed to satisfy two very different user groups who almost certainly have competing priorities. In our previous work, a needs assessment of providers for a post-discharge wound tracking app15, providers expressed concern over additional time requirements, workflow disruption, issues surrounding receipt of photos (e.g. liability, poor quality), and EMR integration. Patient and provider expectations differed on such things as frequency of and trigger for wound tracking: patients expected to track their wound routinely even in the absence of an obvious problem, while providers envisioned less frequent use, generally only if a problem was suspected. Similarly, many of the key patient expectations identified in this paper are subject to provider buy-in and will have to be negotiated between patients and providers. Acute care mHealth apps might ultimately be disruptive, catalyzing a shift from provider-driven to patient-centered care processes.

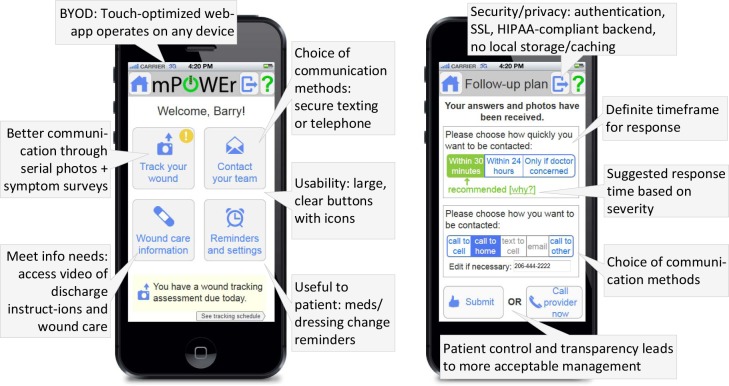

Figure 3 depicts one such mHealth app we are developing to facilitate wound-tracking and patient-provider communication by surgical patients after hospital discharge. We demonstrate how the 11 guiding design considerations have informed the most recent prototype. This prototype is an interactive mockup currently undergoing heuristic evaluation and user testing; concurrently, we are using agile techniques for development of the patient-facing app and provider-facing dashboard.

Figure 3:

Application of design considerations to a wound tracking app. Each callout represents one of the 11 guiding themes that emerged from interviews with patients who experienced post-discharge complications.

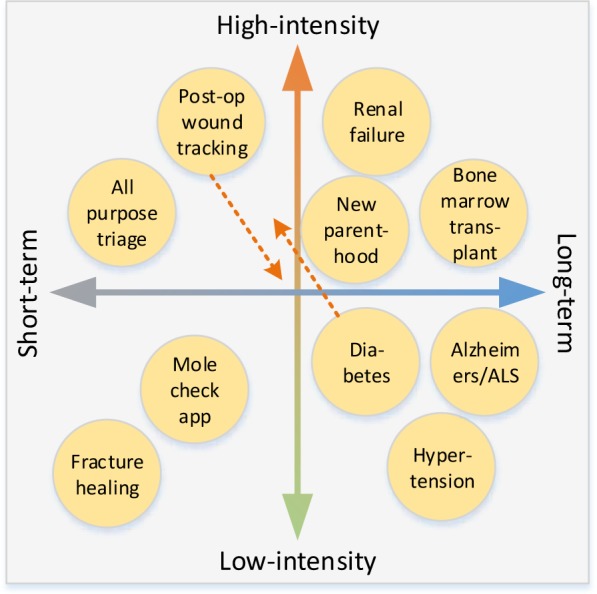

Though the chronic vs. acute distinction is widely used, it may be more useful in generalizing mHealth design considerations to distinguish health conditions along two axes: short-term vs long-term and high-intensity vs low-intensity usage (Figure 4). Typical chronic illnesses tend to be long-term and low intensity while acute concerns tend to be short-term and high intensity, but other conditions (occupying the adjacent quadrants) can have elements of both chronic and acute conditions. Some conditions may even shift around, e.g. short-term, high-intensity surgical wound monitoring may shift to long-term, low-intensity chronic wound monitoring, or stable diabetes may become uncontrolled, shifting toward higher intensity. In designing apps for individual conditions or groups of conditions, it makes sense to consider both intensity and duration, and how these change over time. For example, short-term use may require simplicity and easy learnability, whereas long-term use may allow the possibility of more complexity and customization; high intensity use will require consideration of how to facilitate timely patient-provider communication, whereas low intensity use may not require provider involvement, using algorithmic feedback to patients instead.

Figure 4:

Example mHealth apps by duration and intensity. Dotted orange lines indicate possible shifts based on disease course or progression.

Our research has a number of strengths, including identification of new themes relevant to post-acute mHealth and affirmation of other themes that have been previously reported in the context of chronic illness mHealth. Our findings provide a sound basis for a patient-centered approach to software development, uncommon in the health domain, yet key to developing applications that patients will actually use.

Despite these strengths, this study has several limitations. First, we only interviewed surgical patients. Patients affected by other conditions may have different needs and preferences. We believe ours is a good initial test population due to the challenging and often eventful post-discharge experience following major surgery. Second, we only interviewed patients who experienced post-discharge complications. We believe that patients who experienced problems are the most likely users of the app and have the most insight into current system failings. Lastly, we interviewed a relatively small number of patients from two very different, but related, hospital settings. As is customary in qualitative research, the sample size was based on reaching saturation. In the future we will address some of these issues through user-centered development of our wound-tracking mHealth platform and examine its impact on patient satisfaction, quality of life, clinical outcomes, and healthcare utilization.

Conclusion

Through interviews with patients who experienced post-discharge complications, we explored the design space of a post-acute care mHealth app. Patients described lack of information at discharge, lack of control over communication and mistrust about management decisions made by providers about their care. In response, they envisioned design qualities of an mHealth app that could empower patients through meeting information needs and facilitating predictable communication, and empower their providers with information to make the best decisions about their care. We present a set of design considerations for post-acute care apps and propose a new model for differentiating mHealth apps by the intensity and duration of illness. These contributions incorporate key patient preferences to expand the mHealth landscape with apps that patients will embrace.

Acknowledgments

We thank our participants, the iMed research group, Sarah Han, Cheryl Armstrong, and Mary Ko for their significant contributions. This work was supported by the University of Washington Department of Surgery, the University of Washington AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Research Award (K12 HS019482) and University of Washington NCATS Translational Science Training Grant (TL1 TR000422).

References

- 1.Rhodes KV. Completing the play or dropping the ball? the case for comprehensive patient-centered discharge planning. 2013:24–25. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.7854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibson A, Tevis S, Kennedy G. Readmission after delayed diagnosis of surgical site infection: a focus on prevention using the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Am J Surg. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kazaure HS, Roman SA, Sosa JA. Association of postdischarge complications with reoperation and mortality in general surgery. Arch Surg. 2012;147(11):1000–7. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamasurg.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanger P, Hartzler A, Han SM, Lober WB, Evans HL. Patient Perspectives on Post-Discharge Surgical Site Infections: Towards a Patient-Centered mHealth Solution. 2014. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Patel RA, Klasnja P, Hartzler A, Unruh KT, Pratt W. Probing the benefits of real-time tracking during cancer care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2012;2012:1340–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayes G, Abowd G, Davis J. Opportunities for pervasive computing in chronic cancer care; Pervasive ’08 Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Pervasive Computing; 2008. pp. 262–279. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mamykina L, Mynatt E, Davidson P, Greenblatt D. MAHI: investigation of social scaffolding for reflective thinking in diabetes management; Proceeding of the twenty-sixth annual CHI conference on Human factors in computing systems - CHI ’08; New York. ACM Press: New York, USA; 2008. p. 477. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris LT, Tufano J, Le T, et al. Designing mobile support for glycemic control in patients with diabetes. J Biomed Inform. 2010;43(5 Suppl):S37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klasnja P, Hartzler A, Powell C, Pratt W. Supporting cancer patients’ unanchored health information management with mobile technology. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011;2011:732–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arsand E, Tufano JT, Ralston JD, Hjortdahl P. Designing mobile dietary management support technologies for people with diabetes. J Telemed Telecare. 2008;14(7):329–32. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2008.007001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu LS, Hirano SH, Tentori M, et al. Improving communication and social support for caregivers of high-risk infants through mobile technologies; Proc ACM 2011 Conf Comput Support Coop Work - CSCW ’11; 2011. p. 475. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kientz JA, Arriaga RI, Abowd GD. Baby steps: evaluation of a system to support record-keeping for parents of young children; Proceedings of the 27th international conference on Human factors in computing systems -CHI 09; New York. New York, USA: ACM Press; 2009. p. 1713. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chell E. Critical Incident Technique. In: Symon G, Cassell C, editors. Qualitative Methods and Analysis in Organizational Research: A Practical Guide. London: Sage Publications; 1998. pp. 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory— procedures and techniques. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanger P, Hartzler A, Lober WB, Evans HL. Provider needs assessment for mPOWEr: a Mobile tool for PostOperative Wound Evaluation; Proc. AMIA.; 2013. [Google Scholar]