Abstract

Secure messaging (SM) allows patients to communicate with their providers for non-urgent health issues. Like other health information technologies, the design and implementation of SM should account for workflow to avoid suboptimal outcomes. SM may present unique workflow challenges because patients add a layer of complexity, as they are also direct users of the system. This study explores SM implementation at two Veterans Health Administration facilities. We interviewed twenty-nine members of eight primary care teams using semi-structured interviews. Questions addressed staff opinions about the integration of SM with daily practice, and team members’ attitudes and experiences with SM. We describe the clinical workflow for SM, examining complexity and variability. We identified eight workflow issues directly related to efficiency and patient satisfaction, based on an exploration of the technology fit with multilevel factors. These findings inform organizational interventions that will accommodate SM implementation and lead to more patient-centered care.

Introduction

Secure messaging (SM) is increasingly available as a component of patient portals and allows patients to communicate online with their providers about non-urgent issues through a secure website. SM allows healthcare organizations to provide personal service in an effective and efficient manner, and provides patients with an additional communication channel that is complementary to existing channels (i.e. phone calls and walk-in clinics). The use of SM is positively associated with health outcomes1–3, patient satisfaction2,4, perceived improved patient knowledge and self-care5, adherence6, efficiency7 and cost of care1,8. However, there are also various challenges regarding SM. For example, SM adoption rates among patients are still low9.

Integrating SM into existing practice is of widespread interest, given its inclusion in meaningful use criteria (http://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/achieve-meaningful-use/core-measures-2/use-secure-electronic-messaging, Last accessed on 08/03/2014), yet it poses significant challenges for clinicians10,11. Heyworth et al10 reported that providers’ inability to access the SM system easily was an important challenge possibly leading to less enthusiastic system adoption. Wakefield et al.11 developed a seven-step SM implementation framework. A critical step of the framework was integration with workflow. Organizations that implement SM need to determine who will be involved in SM, who will be responsible for responding to patient messages, and what policies should be in place regarding patient access rights and staff responsibilities. These decisions, specific to organizational context, can lead to either better or worse integration of SM in workflow12,13. These decisions can be carefully planned, but they can also result in unintended consequences if there is a lack of fit between the technology and the work being done11.

The importance of the fit between information technologies and workflow has been discussed in the context of a variety of health information technologies such as electronic health records (EHR)14, barcoding15 and computerized provider order entry (CPOE)16. The boundaries of these technologies are limited to clinical settings and the active users are clinicians and staff. However, workflow considerations for SM are more complex because the system boundaries extend into daily living settings, with patients being active users as well. The design of SM systems should consider these broader boundaries and wider range of users. Clinical workflow for SM (i.e., the component of overall workflow occurring in the clinic) should be sensitive to the workflow in the daily living environment.

Conceptual models that address the design and integration of technology for a work system stress the need to assess the fit between the new technology and workflow at multiple levels. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and its variations mainly focus on individual factors such as perceived usefulness and ease of use17. Organizational theories such as sociotechnical systems theory highlight the importance of the joint optimization of social (e.g. policies) and technical systems for effective functioning of organizations18. The broader cultural, political, and economic environment in which organizations operate also affect technology implementation19. SM implementation may also be affected by factors at each of these levels. However, successful implementation is challenged by requiring attention to all factors simultaneously20.

The purpose of this study is to describe clinical workflows associated with the use of SM, and to identify issues (at multiple levels such as individual, task, organizational and environment) that affect clinical efficiency and effectiveness in primary care settings. Although several studies have demonstrated the positive contribution of SM, workflow challenges may limit the full benefit from SM from being achieved, particularly if adoption rates and use increase. This study examined the research question “What challenges arise when integrating SM use with workflows at different organizational levels?”. Based on our data, many challenges were related to technology fit, and we then explored these challenges using a multilevel framework21 to inform system design and organizational interventions that can lead to more effective SM use and more patient centered care.

Methods

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) began broad enterprise implementation of SM in 2011, after a pilot implementation at several sites. Clinical staff members used an integrated EHR called the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). The SM application is tethered to, but not fully integrated into CPRS. Patients who were in-person authenticated for the VHA’s patient portal and personal health record (My HealtheVet) were able to opt-in to use SM. In the VHA, patients can use SM to contact their primary care providers (and more recently specialists) about non-urgent matters by logging into their My HealtheVet accounts. They are told that a response from the clinical team will occur within three business days. Teams at two study locations, four teams each in New England and the Pacific Northwest, initiated SM use in 2008 as part of a pilot implementation conducted prior to national rollout. While not all providers at these locations participated in SM until the full rollout in 2011, because of their participation as pilot sites, the early adopters had more experience with SM than those at other facilities. This experience allowed us to evaluate how they had incorporated SM into their workflow, defined in this study from an operations perspective, focused on processes and allocated resources. Specifically we defined workflow as a sequence of activities by multiple individuals related to SM utilization22. We conducted twenty-nine individual interviews with the members of eight primary care teams. The eight teams were selected based on variation in the volume of secure messages received during the six months prior to selection for the study and the proportion of messages completed by the provider (physician or nurse practitioner) versus other team members (Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of the study sample

| Team No | Location | Incoming Message Volume in 6 Months | Provider Completion Rate* | Roles of the Interviewees |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | New England | 303 | 0% | Physician, licensed practical nurse (LPN), registered nurse (RN), Pharmacist** |

| 2 | New England | 197 | 0% | Physician, LPN, Pharmacist** |

| 3 | New England | 283 | 20% | Nurse Practitioner, LPN, RN |

| 4 | New England | 329 | 58% | Physician, LPN, RN, Pharmacist |

| 5 | Northwest | 385 | 0% | Physician, LPN, RN, Pharmacist |

| 6 | Northwest | 491 | 0% | Physician, RN, Medical assistant |

| 7 | Northwest | 503 | 73% | Physician, LPN, RN, Social worker |

| 8 | Northwest | 539 | 32% | Physician, LPN, RN, Medical Assistant |

Provider completion rate is the percentage of the secure messages completed by provider (physician or nurse practitioner) by clicking the “Complete” button in the SM system.

The same pharmacist serves both Teams 1 and 2.

Data was collected by MO and BAP from the New England teams in March-June 2013 and by MO, SS, BAP, ES and SW from the Northwest teams in April 2013. Interviews were guided by a semi-structured interview protocol. Interview questions addressed general information about each interviewee’s role on the healthcare team, how SM was used, the integration of SM with daily practice, and team members’ attitudes towards and experiences with SM. Interviews took place in private rooms at each interviewee’s clinic. Each interview lasted approximately 30–45 minutes. All interviews were audiotaped, except for one, and transcribed verbatim. All data collection methods were approved by the VHA Central Institutional Review Board.

Data were qualitatively analyzed in two steps. In the first step, all interviews for a team were read by two of the authors, and each author separately created a summary describing the team’s use of SM. The summary was completed using a semi-structured template, focused around the elements of workflow. The sections of the template included who was interviewed, their roles and responsibilities with respect to secure messages, their impressions of the types of messages received, their description of major process steps in handling secure messages, perceptions of the value of SM, comments about organizational decisions and factors that affected SM workflow, and any technology-related issues that arose. A third author synthesized the other two researchers’ notes to create an overall site summary. In the second step, the authors worked from the site summaries to develop a general workflow diagram. The researchers who analyzed data have backgrounds in medical informatics, industrial engineering, management information systems, health administration, qualitative research and primary care medicine.

Results

Secure Messaging Workflow

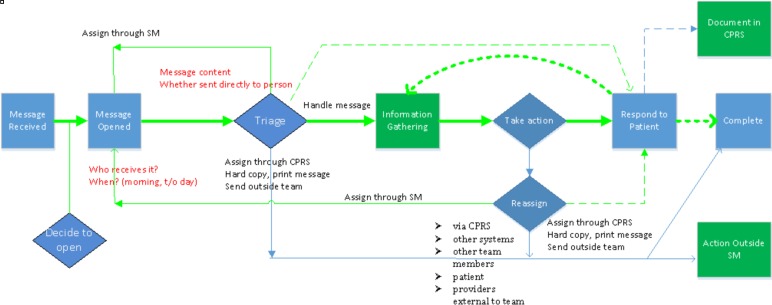

The clinical workflow for SM as described by interviewees and synthesized across the eight teams is illustrated in Figure 1. Figure 1 shows the main activities, the order of these activities and information flow at a high level once a team receives a message from a patient. Messages are usually focused on one request and can be addressed by one staff member. However, some messages included multiple requests and were handled by multiple people.

Figure 1.

Overview of SM workflow across teams

Once a message is opened, the team member reviews the content of the message and identifies the staff member who can best respond to the message based on their scope of practice. The team member who first opened the message often collects additional information (e.g. reviewing patient data in the CPRS system or contacting the patient for further details) and takes necessary action (e.g., request an appointment or refill a prescription). Alternatively, the message might be triaged or assigned through the SM system to another team member. In some cases, the issue was handled outside of SM by notifying another staff in person or via an electronic alert in CPRS.

If a patient requested more than one item for action (e.g. scheduling a new appointment and also providing information about physical therapy resources), then the message was first be handled by one of the team members appropriate to the request (e.g. scheduling clerk) and then reassigned to another team member (e.g. physician).

Once necessary actions were taken, a response was sent to the patient, typically either via SM or by phone. Based on the team member’s judgment, the secure message was copied into CPRS as a clinical note and signed by the team member. All secure messages were required to be completed. This was accomplished by clicking the “Complete” button in the SM system. Replying to a message also automatically generated the option to simultaneously complete the message. Completing a message was designed to signal that the issue raised by the patient was resolved, and the message no longer appeared in the team member’s Inbox. VHA policy requires completing messages within three business days; otherwise, the message is flagged as “Escalated”.

The clinical workflow for SM can be complex because it includes various decision points, requires the cooperation of clinical team members, and exists in tandem with other workflows focused on responding to patients (e.g., telephone calls, walk-ins). On occasion, it was necessary to reach the patient for further information and clarification in order to proceed. If the patient’s question was multifaceted, interviewees noted that it was often more expeditious to follow up with patients directly by phone, although patients were not always available to ensure timely contact. While the SM platform was the same across sites, clinics varied in terms of size, locale, patient demographics, physical layout, and organizational structure. In addition, each clinic and the teams within these clinics made local organizational decisions about how to embed SM into their existing workflows. These differences and decisions led to variability in the clinical workflow for SM across the care delivery teams. Our analysis revealed two major workflow variations across teams. Variations occurred in how team members used the SM system, and how teams communicated with other staff members and patients outside of the SM system.

Differences were found both in how messages were received and how team members responded to messages. Depending on the team and situation, there was significant variation in which team member was responsible for opening messages. For example, on one team an LPN was the first to open all incoming messages. On another, registered nurses and LPNs shared the responsibility of opening messages. In yet other settings, physicians opened messages first. In four of the teams, the providers did not personally use the SM system, relying on team members to relay the information. (Note that these team members were intentionally selected to be interviewed based on their low provider completion rate.) In other teams, physicians acted on and directly responded to patient messages using the SM system.

In part because of differences in how roles and responsibilities were defined with respect to SM, message resolution was handled using a variety of means of communication. For example, providers who did not use the SM application accessed information through in-person consultations with staff, via printed copies of messages, or through CPRS notifications. Other team members called patients to respond to the issues raised in a secure message, rather than replying within the application. Although the use of multiple channels provides convenience and facilitates communication, it can also affect the team’s ability to track message handling via the SM application. For example, if the staff member who opened the message forwards the message verbally and then closes the message, reviewing a secure message thread within the system may not reveal when or whether the issue was actually resolved.

Workflow Issues

Most interviewees believed the SM system was of value to patients, providing an alternate access channel and a potentially richer way to communicate. However, they were more mixed in their assessment of how well the system worked. We examined several workflow issues raised by interviewees and conceptualized the source of these issues as a lack of fit between the technology and multiple levels of work. Karsh et al.21 discussed technology-work misfit at four interrelated levels: user, task, organization and environmental levels. In Table 2, we describe technology-work fit at different levels from Karsh et al.’s model, and identify specific workflow issues from our findings.

Table 2.

Levels of technology fit, description of levels and findings related to workflow issues at different work levels

| Level | Description of the Level from Karsh et al. | Workflow Issues Identified |

|---|---|---|

| User-technology fit | “Fit between technology and user characteristics (e.g., values, attitudes, abilities)” | 1. Use among team members varies due to their abilities, attitudes and values 2. Inappropriate use of messaging by patients |

| Task-technology fit | “Fit between technology and health care task characteristics (e.g., complexity, time constraints) ” | 3. SM was tethered, but not integrated, into the electronic record 4. Technology-related issues (e.g., frequent log offs, time required to log onto second system) |

| Organization-technology fit | “Fit between technology and organizational characteristics (e.g., policies, practices, social climate, resources)” | 5. Need for additional policies (e.g. access by family members, identification of surrogates) 6. Additional workload 7. Despite the significant impact on workload, there was no workload credit for SM. |

| Environment-technology fit | “Fit between technology and the external (e.g. politics, culture) or internal (e.g., lighting, layout, noise) environment” | 8. Patient expectations of early response |

User-technology fit

At the user level, we observed two workflow issues related to technology fit. First, some nurses and providers preferred not to use the SM system while others were enthusiastic users. Some team members were not comfortable with computers, while others found the system burdensome (i.e. using SM required them to log in to another system and to keep several applications open simultaneously). Enthusiastic users often took on a greater role within the SM workflow (e.g. opening all messages), while others used alternative communication channels, such as telephones to respond to patients. Second, several types of messages described by interviewees suggested patients may use the system inappropriately, thereby impacting workflow. We identified two broad areas of inappropriate use by patients: 1. sending a message for an urgent issue such as chest pain, and 2. sending long messages that also included personal information not directly relevant to their health condition and request.

Task-technology fit

At the VHA, SM is not integrated with the primary existing clinical information system, CPRS. Use of the SM system therefore requires opening an additional window in the computer screen and an additional login. Moreover, because SM is not integrated into CPRS, clinicians juggle between windows to locate pertinent information such as test results to copy and paste to the SM screen. This not only is additional work, but also presents potential safety and privacy concerns23,24. Several interviewees also raised the issue of the inconvenience of not being able to send information (e.g. lab results) from CPRS. Other aspects of the technology also interfere with workflow tasks. For example, for privacy and security reasons, the SM software automatically times out when not in use.

Organization-technology fit

Three workflow issues were identified. First, because SM is a new communication channel between patients and providers, new situations arise that require additional policies. For example, SM accounts might be used by family members (i.e., informal caregivers) on behalf of patients. This situation has not been officially addressed by organizational policies, and staff members used their judgment in how to handle confidentiality when they communicated about with family members about patients. Another example was ensuring timely response to SM when a provider was off duty. Although CPRS enables identification of surrogates for CPRS alerts, a duplicate, separate arrangement must be made in the SM system. Second, some organizational practices create additional workload. Some sites had decided that every secure message should be copied by the team user into CPRS – a task requiring manual intervention. Finally, the use of SM was not formally counted as a part of workload credit. Several interviewees saw this as a significant barrier to use, particularly as the volume of messages has grown.

Environment-technology fit

At the level of the environment, we identified one workflow issue. VHA expects clinical teams to respond and complete patient messages within three business days. On the other hand, patients may expect a same-day or faster response. The expectations of patients for quick responses has also been documented in previous studies25. Patients who do not get a response on the same day may be upset, and they may send additional messages or follow up by telephone to repeat their requests and reflect their frustration.

Discussion

We studied the implementation of SM in eight primary care delivery teams within the VHA. The complexity of the clinical workflow for SM, shown in Figure 1, makes it challenging to develop a SM system that fits with existing work at all levels, across many sites. Across sites, variation occurred at the user, task, organization, and environmental levels, both before and in response to implementation. Based on our data, we examined the issue of fit between the technology and four levels of work, and categorized workflow issues described by interviewees in terms of these levels. A limitation of our work is that it is based on a single organization, and a study sample of eight teams, which may limit the range of workflow challenges.

The value of using a multi-level framework to examine technology fit is that it underscores the need for strategies to mitigate issues in both the technical and organizational spheres, and at different organizational levels. Design and implementation strategies for health information technologies should recognize these levels, and the relationships between them.

Implementation strategies should seek to determine where lack of fit between technology and workflow is occurring, then develop responses to improve the fit. Responses can include both changes in technology design as well as organizational practices. In terms of technology design, in the context of this study, several refinements to the SM system would improve task-technology fit, eliminating what interviewees’ perceived as difficulties or time-wasting workarounds. For example, a key improvement from the interviewees’ perspective would be integrating the SM system with existing information systems. Such a change might increase the engagement of providers with the system, reduce total workload in the clinic and potentially reduce variability across sites. In terms of user-technology fit focused on patients, systems might be developed that flag key words in messages – such as chest pain – that direct the patient to call rather than to send a secure message.

To increase fit, implementation can also address organizational practices at multiple levels. For example, in our context, user-technology fit might be improved by more effective training of clinicians and patients. Effective training may increase adoption among staff members and decrease inappropriate use of the SM by patients. Organization-technology fit can be improved by developing policies or guidance to address areas of uncertainty, such as when a secure message should be copied to the EHR or who will open messages first. As the number of patients using SM and message volume increase, a policy to address workload is particularly important. Environment-technology fit can be improved by providing guidance to patients about the best use of the system, with personalized training to patients when needed.

Conclusion

The clinical workflow for SM is complex and includes variations as an SM system is implemented in different clinic settings. The direct involvement of patients as users also contributes to its complexity. Based on interview data, we identified eight workflow issues that emerged in an SM implementation, and used a multi-level technology-fit framework to examine them. To improve fit, design and implementation strategies should encompass both technical improvements and organizational practices, and be sufficiently comprehensive to address workflow issues at different levels. While this study was based on data from a single organization and SM system, which influenced to some extent the issues identified, the multi-level framework and analysis of fit are applicable for any system and organization. With the emphasis on SM in meaningful use criteria, which is likely to increase the number of patients using SM and the overall volume of messages, organizations need insights about how to implement SM systems to ensure that SM increases access to providers, improves communication and eventually leads to more effective, timely, patient centered and safe care.

Workflow issues have been explored in other technology studies (e.g. EHR, CPOE), but SM workflow differs because patients are also active users. We identified two workflow issues related to patient use, including inappropriate use of messaging by patients and patients’ expectation of quick (often 24 hour or sooner) response. Both issues relate directly to patient satisfaction and influenced staff workflow. Because the study design focused on staff interviews, our results emphasize the importance of effective communication between patients and staff, to provide relevant information without requiring additional rounds of messages or phone calls. Our future research includes an analysis of messages between the patients and clinics to better understand communication patterns. From a system design perspective, templates that can structure patient interactions have been shown to be effective26. Examining SM use from the patients’ perspective, in daily living environments, is also likely to be a fruitful area for additional research.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Veterans Health Administration (QUERI RRP 11–409, PI: Woods), with additional support from the New England Veterans Engineering Resource Center. We would like to thank the members of the eight PACT teams who agreed to be interviewed.

References

- 1.Zhou YY, Kanter MH, Wang JJ, Garrido T. Improved quality at Kaiser Permanente through e-mail between physicians and patients. Health Aff. 2010 Jul;29(7):1370–5. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wade-Vuturo AE, Mayberry LS, Osborn CY. Secure messaging and diabetes management: experiences and perspectives of patient portal users. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013 May 1;20(3):519–25. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris LT, Koepsell TD, Haneuse SJ, Martin DP, Ralston JD. Glycemic control associated with secure patient-provider messaging within a shared electronic medical record: a longitudinal analysis. Diabetes Care. 2013 Sep;36(9):2726–33. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin C-T, Wittevrongel L, Moore L, Beaty BL, Ross SE. An Internet-based patient-provider communication system: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7:e47. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.4.e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woods SS, Schwartz E, Tuepker A, Press NA, Nazi KM, Turvey CL, et al. Patient experiences with full electronic access to health records and clinical notes through the My HealtheVet Personal Health Record Pilot: qualitative study. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e65. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muller D, Logan J, Dorr D, Mosen D. The effectiveness of a secure email reminder system for colorectal cancer screening. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2009;2009:457–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liederman EM, Morefield CS. Web Messaging: A New Tool for Patient-Physician Communication. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2003;10:260–70. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reid RJ, Fishman PA, Yu O, Ross TR, Tufano JT, Soman MP, et al. Patient-centered medical home demonstration: a prospective, quasi-experimental, before and after evaluation. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:e71–e87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimada SL, Hogan TP, Rao SR, Allison JJ, Quill AL, Feng H, et al. Patient-provider secure messaging in VA: variations in adoption and association with urgent care utilization. Med Care. 2013 Mar;51(3 Suppl 1):S21–8. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182780917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heyworth L, Clark J, Marcello TB, Paquin AM, Stewart M, Archambeault C, et al. Aligning medication reconciliation and secure messaging: qualitative study of primary care providers’ perspectives. J Med Internet Res. 2013 Jan;15(12):e264. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wakefield DS, Mehr D, Keplinger L, Canfield S, Gopidi R, Wakefield BJ, et al. Issues and questions to consider in implementing secure electronic patient-provider web portal communications systems. Int J Med Inform. 2010 Jul;79(7):469–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ancker JS, Kern LM, Abramson E, Kaushal R. The Triangle Model for evaluating the effect of health information technology on healthcare quality and safety. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 19(1):61–5. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bohmer RMJ. The Four Habits of High-Value Health Care Organizations. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2045–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1111087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ash JS, Bates DW. Factors and forces affecting EHR system adoption: report of a 2004 ACMI discussion. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12(1):8–12. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patterson ES, Cook RI, Render ML. Improving patient safety by identifying side effects from introducing bar coding in medication administration. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2002;9(5):540–53. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ash JS, Sittig DF, Poon EG, Guappone K, Campbell E, Dykstra RH. The extent and importance of unintended consequences related to computerized provider order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14(4):415–23. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, Davis FD. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003;27(3):425–78. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasmore WA. Designing Effective Organizations: The Sociotechnical Systems Perspective. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blumenthal D. Stimulating the adoption of health information technology. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1477–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0901592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holden RJ, Karsh B-T. A Review of Medical Error Reporting System Design Considerations and a Proposed Cross-Level Systems Research Framework. Hum Factors J Hum Factors Ergon Soc. 2007 Apr 1;49(2):257–76. doi: 10.1518/001872007X312487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karsh B-T, Escoto KH, Beasley JW, Holden RJ. Toward a theoretical approach to medical error reporting system research and design. Appl Ergon. 2006 May;37(3):283–95. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ozkaynak M, Brennan PF, Hanauer Da, Johnson S, Aarts J, Zheng K, et al. Patient-centered care requires a patient-oriented workflow model. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(e1):e14–6. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-001633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thielke S, Hammond K, Helbig S. Copying and pasting of examinations within the electronic medical record. Int J Med Inform. 2007 Jun;76(Suppl 1):S122–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siegler EL, Adelman R. Copy and paste: a remediable hazard of electronic health records. Am J Med. 2009 Jun;122(6):495–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Couchman GR, Forjuoh SN, Rascoe TG, Reis MD, Koehler B, Van Walsum KL. E-mail communications in primary care: what are patients’ expectations for specific test results? Int J Med Inform. 2005 Jan;74(1):21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leventhal T, Taliaferro JP, Wong K, Hughes C, Mun S. The patient-centered medical home and health information technology. Telemed J E Health. 2012 Mar;18(2):145–9. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2011.0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]