Abstract

Background

This study examined possible income differences in the impact of a national reimbursement policy for smoking cessation treatment and accompanying media attention in the Netherlands in 2011.

Methods

We used three waves of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Netherlands Survey, a nationally representative longitudinal sample of smokers aged 15 years and older (n=1,912). The main analyses tested trends and income differences in outcome measures (smokers’ quit attempt rates, use of behavioral counseling, use of cessation medications, and quit success) and awareness variables (awareness of reimbursement possibilities, the media campaign, medications advertisements and other media attention) with Generalized Estimating Equations analyses.

Results

In the first half of 2011, there was a significant increase in quit attempts (Odds Ratio (OR) = 2.02, p < 0.001) and quit success (OR = 1.47, p < 0.001). Use of counseling and medications remained stable at 3% of all smokers in this period. Awareness of reimbursement possibilities increased from 11% to 42% (OR = 6.38, p < 0.001). Only awareness of the media campaign was associated with more quit attempts at the follow-up survey (OR = 1.95, p < 0.001). Results were not different according to smokers’ income level.

Conclusions

The Dutch reimbursement policy with accompanying media attention was followed by an increase in quit attempts and quit success, but use of cessation treatment remained stable. The impact of the policy and media attention did not seem to have decreased or increased socioeconomic inequalities in quit attempts, use of cessation treatment, or quit success.

Keywords: Netherlands, public policy, reimbursement, smoking cessation, social class

INTRODUCTION

Smoking tobacco is highly addictive and smoking cessation leads to withdrawal symptoms, making it difficult for smokers to stay tobacco-free (USDHHS 2010). There are various behavioral smoking cessation interventions and medications available on the market to help smokers quit smoking. Despite the availability of treatment, many smokers attempt to quit smoking without the use of assistance (Shiffman et al. 2008, Borland et al. 2012). Reasons for not using treatment include financial barriers (Gross et al. 2008, Willems et al. 2013). Financial barriers can be reduced by reimbursement policies for smoking cessation. Such policies may be more effective among smokers with lower income levels, because the use of cessation treatment is lower in this group (Shiffman et al. 2008) and the price of treatment may be a barrier for them (Giskes et al. 2007). This is important, because smokers with lower income levels smoke more cigarettes per day and have lower quit rates than smokers with higher income levels (Siahpush et al. 2006, Nagelhout, De Korte-de Boer et al. 2012).

A recent review concluded that reimbursing smokers for their use of smoking cessation treatment increased the use of treatment, the number of attempts to quit smoking and the number of successful quit attempts (Reda et al. 2012). However, income differences were not reported. In fact, few original studies have looked at income differences. Tremblay et al. (2009) examined differences in the use of a reimbursement policy in a province of Canada (Quebec). Their findings suggest that the reimbursement policy was more effective in reaching financially disadvantaged smokers, as evidenced by greater use of reimbursed cessation medications by employment assistance recipients than other insured persons. Furthermore, stop smoking services have been successful in reaching financially disadvantaged smokers in the United Kingdom (Bauld et al. 2007, West et al. 2013). However, these services have specifically focused on reaching this group by using targeted media campaigns, basing and promoting smoking cessation services in deprived areas, and offering an exemption from paying the (small) prescription charge for medications for people on low incomes (Bauld et al. 2007, Murray and McNeill 2012, West et al. 2013). It is unclear whether a national reimbursement policy that does not focus on reaching low income smokers could achieve similar effects.

In January 2011, a national reimbursement policy for smoking cessation treatment was implemented in the Netherlands. Behavioral counseling was already reimbursed prior to 2011 and, depending on their particular insurance package, some smokers were already able to get a reimbursement for cessation medications (nicotine replacement therapy and prescription medications) from their supplementary insurance. Because the combination of cessation medications and behavioral counseling is most effective in helping smokers to quit (Hartmann-Boyce et al. 2013), medications were only reimbursed to smokers provided that they also participated in multi-session evidence-based behavioral counseling (face-to-face, group, or telephonic counseling). Once a year, smokers could claim full reimbursement for smoking cessation treatment from their health insurance company. This was paid only after spending the mandatory deductible of 170 Euro per year for any health care costs. This means that smokers were only fully reimbursed when they had completed their deductible.

The implementation of the reimbursement policy was accompanied by a media campaign that ran from December 2010 to January 2011. This campaign explained the reimbursement policy and focused on motivating smokers to quit smoking with the use of behavioral counseling and cessation medications (Willems et al. 2012). There was also an increase in commercial advertisements about cessation medications from the pharmaceutical industry and some of these communicated the new reimbursement possibilities. Finally, there were numerous news stories about the policy on television, on the radio, in newspapers, and on the internet. Media attention that increases the awareness of the reimbursement policy can potentially be important to increase the use of the reimbursement and the level of smoking cessation (Reda et al. 2012). Therefore, it is important to take media attention into account when studying the impact of a reimbursement policy.

The reimbursement policy in the Netherlands was discontinued after one year due to government budget cuts. This provides a unique opportunity to examine the impact of this policy under real-world conditions. In a previous study, we examined the impact of the reimbursement policy with a sample of smokers that was followed until six months after policy implementation (Nagelhout et al. in press). In the current study, we also conducted a survey when the policy was already discontinued. This design has the advantage of functioning as a within-country natural experiment.

The following research questions were examined:

Are there changes in quit attempts, use of behavioral counseling, use of cessation medications, and quit success through time?

Are there changes in awareness of reimbursement possibilities and awareness of media attention about the reimbursement through time?

Are awareness of reimbursement possibilities and awareness of media attention about the reimbursement associated with quit attempts, use of behavioral counseling, use of cessation medications, and quit success?

Are the findings from research questions 1 to 3 different for low, medium, and high income smokers?

METHODS

Design

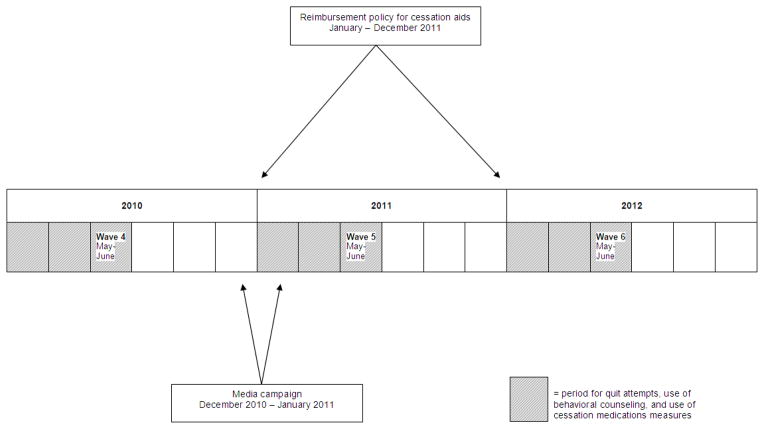

In this study, we used three survey waves of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Netherlands Survey. One wave of the survey was conducted before the implementation of the national reimbursement policy (wave 4 in 2010), one wave was conducted after the policy was implemented (wave 5 in 2011), and one wave was conducted after the policy was discontinued (wave 6 in 2012). Figure 1 shows a timeline with the survey waves, the implementation and discontinuation of the reimbursement policy and the timing of the media campaign. As can be seen in Figure 1, the survey waves were in May and June of each year. Because this does not correspond with the policy timing from January to December, the measures of quit attempts, use of behavioral counseling and use of cessation medications were restricted to the last six months before the survey wave, as highlighted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Timeline of 2010, 2011 and 2012 with the survey waves, the implementation of the reimbursement policy, the timing of the media campaign, and the period for the quit attempts, use of behavioral counseling, and use of cessation medications measures.

Sample

A large probability-based web database from TNS NIPO was used to recruit Dutch smokers aged 15 years and older. More information about the baseline Dutch web survey can be found elsewhere (ITC Project, 2009, Nagelhout et al. 2010). In follow-up surveys of the ITC cohorts, samples are replenished at each wave to maintain a sample size of approximately 2,000 respondents per wave (Thompson et al. 2006).

Of the 1,961 respondents from wave 4, 1,567 (79.9%) participated in wave 5. In wave 5, a replenishment sample of 482 respondents was added. Of the 2,049 respondents from wave 5, 1,736 (84.7%) participated in wave 6. A replenishment sample of 286 respondents was added in wave 6. Respondents who were lost to follow-up were younger, more likely to be female, higher educated, and more likely to be a heavier smoker than respondents who participated in the follow-up surveys (Nagelhout, De Vries et al. 2012).

To answer research questions 1 and 2, all respondents (including the replenishment samples) from wave 4, wave 5 and wave 6 who smoked at the previous wave (e.g. for wave 6, only those who smoked at wave 5) were included in the analyses (between 1,912 and 1,971 smokers per wave). In the multivariate analyses for research questions 1 and 2, only respondents who participated in all three waves, who smoked at the previous wave, and who answered all questions that we used in the analyses were included (n = 845). To answer research question 3, only respondents who participated in wave 5 and 6, who were smokers in wave 5, and who answered all questions that we used in the analyses were included (n = 991).

Measures

Control variables

Multivariate analyses were adjusted for gender, age group, and heaviness of smoking. Age was categorized as 15 to 24, 25 to 39, 40 to 54, and 55 years and older. The Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI) was created as the sum of two categorized measures: number of cigarettes per day and time before smoking the first cigarette of the day (Heatherton et al. 1989). HSI values ranged from 0 to 6 and have been found to be positively associated with nicotine dependence (Heatherton et al. 1989).

Income level

Monthly gross household income was categorized into three levels: low (less than 2,000 Euro), medium (2,000 to 3,000 Euro) and high (more than 3,000 Euro). Respondents who did not answer the income question were recorded in a separate category.

Awareness variables

Awareness of reimbursement possibilities was measured by asking respondents whether they thought they were eligible for reimbursement for the use of cessation medications. This variable was dichotomized as (1) “yes” and (0) “no” or “don’t know”.

Awareness of the media campaign about the reimbursement policy was measured by asking respondents how often they saw the television commercial, heard the radio commercial, saw any of the posters or noticed something on the internet from this specific media campaign. Respondents answered these four separate questions on a 4-point scale from (0) “never” to (3) “often”.

An index was created by computing a mean score of awareness of the four different parts of the campaign for every respondent, ranging from 0 to 3. Awareness of advertisements for cessation medications was measured by asking respondents how often they noticed advertisements for cessation medications. Respondents could answer this on a 4-point scale from (0) “never” to (3) “often”.

Awareness of (other) media attention about the reimbursement policy was measured by asking respondents how often they saw or heard something in the media about health insurance reimbursement of cessation medications. This question also had a 4-point response scale from (0) “never” to (3) “often”.

Outcome measures

Quit attempts were measured with the question: “Have you made any attempts to stop smoking since the last survey?” (Hyland et al. 2006, Kahler et al. 2009). Respondents who answered in the affirmative were asked in which month they started their attempt to quit smoking. A variable was created that categorized whether respondents started a quit attempt since January of the survey year or not.

Use of behavioral counseling was measured by asking respondents whether they received advice or information about quitting smoking from a local stop-smoking service, such as a stop-smoking course, counseling from a nurse or from a specialized nurse practitioner in the last six months (Borland et al. 2012).

Use of cessation medications was measured by asking respondents whether they used any nicotine replacement therapy or prescription medications in the past year (Fix et al. 2011, Borland et al. 2012). Affirmative responses were restricted to respondents who attempted to quit smoking since January of the survey year.

Quit success was assessed by asking respondents who had attempted to quit whether they were back to smoking or still stopped. Respondents who were still stopped, or who were back to smoking but reported smoking less than once a month, were defined as successful quitters. Respondents who did not attempt to quit, or who were back to smoking more than once a month, were defined as smokers (Hyland et al. 2006).

Ethics

The surveys were cleared for ethics by the Research Ethics Board of the University of Waterloo (ORE #19425).

Analyses

All analyses were performed with SPSS version 19.0 and were weighted by age and gender to be representative of the smoker population in the Netherlands (ITC Project, 2009).

Trends and income differences in outcome measures (research question 1) and awareness variables (research question 2) were tested with Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) analyses. This technique extends multivariate regression analysis to allow for longitudinal analysis of repeated measures in which observations from individuals who completed multiple survey waves are correlated. The dependent variables quit attempts, use of behavioral counseling, use of cessation medications, quit success, and awareness of reimbursement possibilities were dichotomous measures and, therefore, the binomial distribution was used and the logit link (Ballinger, 2004). The other awareness variables were measured on a scale from 0 to 3. These analyses used the normal distribution and the identity link (Ballinger, 2004). Survey wave was designated as the repeated measure variable and the variables of interest were income level and (in separate analyses) the interactions between income level and survey wave (research question 4). All GEE analyses were adjusted for the above mentioned control variables. The unstructured correlation structure was used because this closely approximates the true correlation structure in large samples (Jin, 2011). We performed sensitivity analyses with the exchangeable correlation structure and found that this did not change our results (data not shown).

The associations between awareness variables on wave 5 with outcome measures on wave 6 (research question 3) were tested with multivariate logistic regression analyses, while controlling for the above mentioned control variables. Interactions between income level and awareness variables were added to separate regression analyses (four interactions per analysis) to examine whether there were income level differences in the associations between awareness variables and outcome measures (research question 4).

To adjust for multiple comparisons (8 GEE models and 4 regression models), estimates were considered to be significant when the p-value was below 0.004 (0.05/12) (Bland and Altman, 1995).

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Sample characteristics for wave 4, wave 5, and wave 6 are shown in Table 1. Notable is that a relatively large group of respondents (27–28%) did not answer the question about their income. There were no significant differences between the distributions of sample characteristics between waves.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics on wave 4 (n = 1,912), wave 5 (n = 1,971) and wave 6 (n = 1,919) among respondents who smoked at the previous wave.

| 2010 (wave 4) | 2011 (wave 5) | 2012 (wave 6) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male (%) | 52.8 | 53.6 | 54.4 | χ2 = 0.06, p = 0.970 |

| Female (%) | 47.2 | 46.4 | 45.6 | |

| Age group | ||||

| 15–24 years (%) | 15.2 | 25.3 | 16.9 | χ2 = 5.73, p = 0.454 |

| 25–39 years (%) | 27.2 | 30.7 | 26.6 | |

| 40–54 years (%) | 31.9 | 24.1 | 30.0 | |

| 55 years and older (%) | 25.7 | 19.8 | 26.5 | |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Daily smoker (%) | 80.1 | 75.4 | 74.9 | χ2 = 2.55, p = 0.636 |

| Occasional smoker (%) | 8.3 | 6.8 | 6.1 | |

| Ex-smoker (%) | 11.6 | 17.8 | 19.0 | |

| Heaviness of smokinga | F = 2.64, p = 0.072 | |||

| Mean | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.4 | |

| SD | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.5 | |

| Income level | ||||

| Low (%) | 21.8 | 21.3 | 21.6 | χ2 = 0.14, p = 0.999 |

| Medium (%) | 21.7 | 20.1 | 20.5 | |

| High (%) | 29.4 | 30.8 | 30.0 | |

| No answer (%) | 27.1 | 27.9 | 27.9 | |

On a scale from 0 to 6.

Differences in outcome measures

As can be seen in Table 2, the quit attempt rate was 14% in wave 4, 17% in wave 5, and 15% in wave 6. A multivariate GEE analysis (Table 4) confirmed the increase in quit attempts between wave 4 and 5 (Odds Ratio (OR) = 2.02, p < 0.001) and between wave 4 and 6 (OR = 1.67, p < 0.001). An additional analysis in which the reference category for the survey wave was changed to wave 5 (not shown in tables) revealed that the change between wave 5 and 6 was not significant (OR = 0.83, p = 0.087).

Table 2.

Percentage of smokers by income level and wave who attempted to quit smoking, who used behavioral counseling to quit smoking, and who quit smoking successfully.

| 2010 (wave 4) | 2011 (wave 5) | 2012 (wave 6) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All smokers | n = 1,912 | n = 1,971 | n = 1,919 |

| Quit attempt (% yes) | |||

| Low income level | 13.1 | 16.1 | 15.7 |

| Medium income level | 12.7 | 17.6 | 13.5 |

| High income level | 12.6 | 18.2 | 15.1 |

| Total group | 13.9 | 16.8 | 14.5 |

| Use of behavioral counseling (% yes) | |||

| Low income level | 3.1 | 2.9 | 3.9 |

| Medium income level | 5.3 | 4.8 | 2.5 |

| High income level | 1.6 | 4.8 | 2.4 |

| Total group | 2.7 | 3.4 | 2.8 |

| Use of cessation medications (% yes) | |||

| Low income level | 3.3 | 3.6 | 3.6 |

| Medium income level | 2.4 | 4.1 | 1.5 |

| High income level | 1.4 | 1.5 | 4.5 |

| Total group | 2.6 | 2.7 | 3.0 |

| Quit success (% yes) | |||

| Low income level | 9.1 | 12.7 | 15.9 |

| Medium income level | 14.4 | 21.4 | 20.9 |

| High income level | 11.9 | 20.4 | 21.2 |

| Total group | 11.6 | 17.8 | 19.0 |

| All smokers who tried to quit smoking | |||

| Use of behavioral counseling (% yes) | n = 271 | n = 338 | n = 287 |

| Low income level | 5.5 | 9.0 | 6.2 |

| Medium income level | 11.5 | 14.5 | 3.8 |

| High income level | 2.8 | 10.9 | 5.7 |

| Total group | 7.2 | 9.7 | 3.5 |

| Use of cessation medications (% yes) | |||

| Low income level | 25.5 | 22.4 | 23.1 |

| Medium income level | 18.9 | 23.2 | 11.3 |

| High income level | 11.3 | 8.2 | 29.9 |

| Total group | 18.8 | 16.3 | 20.4 |

| Quit success (% yes) | |||

| Low income level | 29.6 | 22.4 | 32.3 |

| Medium income level | 32.1 | 40.6 | 49.1 |

| High income level | 21.1 | 34.5 | 23.0 |

| Total group | 25.2 | 31.2 | 32.9 |

Table 4.

Summary of eight GEE analyses among respondents who smoked at the previous wave in which income level and wave are used as predictors of (1) quit attempts, (2) use of behavioral counseling, (3) use of cessation medications, (4) quit success, and awareness of (5) the reimbursement policy, (6) the campaign, (7) advertisements for cessation medications, and (8) other media attention about the reimbursement policy.

| 1. Quit attempt (n = 845) OR† (95% CI) |

2. Use of behavioral counseling (n = 845) OR (95% CI) |

3. Use of cessation medications (n = 845) OR (95% CI) |

4. Quit success (n = 845) OR (95% CI) |

5. Awareness of reimbursement possibilities (n = 845) OR (95% CI) |

6. Awareness of the campaign about the reimbursement policya (n = 845) Beta (95% CI) |

7. Awareness of advertisements for cessation medications (n = 845) Beta (95% CI) |

8. Awareness of (other) media attention about the reimbursement policy (n = 844) Beta (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income levelb | p = 0.222 | p = 0.335 | p = 0.704 | p = 0.205 | p = 0.523 | p = 0.487 | p < 0.001 | p = 0.059 |

| No answer | 0.82 (0.61 to 1.12) | 0.80 (0.43 to 1.49) | 1.09 (0.58 to 2.05) | 1.06 (0.84 to 1.33) | 0.87 (0.67 to 1.14) | 0.05 (-0.04 to 0.15) | -0.22 (-0.33 to -0.11)* | -0.10 (-0.19 to -0.01) |

| Low | 1.10 (0.80 to 1.52) | 0.94 (0.50 to 1.76) | 1.31 (0.67 to 2.57) | 0.94 (0.72 to 1.23) | 0.97 (0.74 to 1.27) | 0.07 (-0.03 to 0.17) | -0.08 (-0.19 to 0.04) | -0.03 (-0.12 to 0.06) |

| Medium | 1.07 (0.78 to 1.48) | 1.37 (0.78 to 2.39) | 1.44 (0.75 to 2.76) | 1.19 (0.96 to 1.48) | 1.07 (0.82 to 1.41) | 0.07 (-0.04 to 0.17) | 0.02 (-0.08 to 0.12) | 0.03 (-0.06 to 0.12) |

| High | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Wavec | p < 0.001 | p = 0.041 | p = 0.051 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |

| 4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 5 | 2.02 (1.57 to 2.60)* | 1.70 (1.10 to 2.64) | 1.90 (1.10 to 3.27) | 1.47 (1.27 to 1.71)* | 6.83 (5.55 to 8.40)* | - | 0.25 (0.19 to 0.32)* | 1.05 (0.98 to 1.12)* |

| 6 | 1.67 (1.30 to 2.14)* | 1.21 (0.74 to 1.97) | 1.74 (1.04 to 2.92) | 1.84 (1.59 to 2.13)* | 1.37 (1.07 to 1.75) | - | -0.10 (-0.16 to -0.03)* | 0.48 (0.42 to 0.54)* |

|

| ||||||||

| Income * waved | p = 0.696 | p = 0.335 | p = 0.019 | p = 0.615 | p = 0.310 | p = 0.203 | p = 0.023 | |

All GEE coefficients are adjusted for gender, age group, and heaviness of smoking.

To adjust for multiple comparisons, estimates are considered significant when the p-value is below 0.004.

Questions about awareness of the campaign were only asked directly after the campaign ran, in wave 5. Therefore, ‘wave’ is not used as a predictor in this GEE analysis.

p-value for overall 3 df test for income

p-value for overall 2 df test for wave

p-value for overall 6 df test for income by wave interaction (separate analyses)

Use of behavioral counseling was somewhat higher in wave 5 than in wave 4, both among all smokers and among smokers who attempted to quit smoking (Table 2). However, this increase was not significant at the p < 0.004 level that we used to adjust for multiple comparisons in the GEE analysis among all smokers (OR = 1.70, p = 0.017) (Table 4). The increase among smokers who attempted to quit smoking was not tested because the sample size was too small (about 300 smokers per wave). For the same reason, this was also not tested for use of cessation medications and quit success.

Use of cessation medications remained stable at 3% of all smokers across waves (Table 2). This was confirmed in the GEE analysis (Table 4), which did not show a significant change between waves.

In wave 4, 12% of all smokers and 25% of smokers who tried to quit smoking reported to have quit successfully (Table 2). In wave 5, this increased to 18% of all smokers and 31% of smokers who tried to quit smoking. The quit success rates increased further in wave 6. A GEE analysis among all smokers (Table 4) confirmed the increased quit success between wave 4 and 5 (OR = 1.47, p < 0.001) and between wave 4 and 6 (OR = 1.84, p < 0.001). An additional analysis (not shown in tables) confirmed the increase between wave 5 and 6 (OR = 1.25, p < 0.001).

There were no significant income differences in quit attempts, use of behavioral counseling, use of cessation medications, or quit success for all waves together (Table 4). Also, there were no significant interactions between income level and survey wave. This means that there were no income differences in the increase in quit attempts and quit success after the implementation of the reimbursement policy.

Differences in awareness variables

Table 3 shows that awareness of reimbursement possibilities, medications advertisements, and other media attention was higher in wave 5 than in waves 4 and 6. This corresponds with the fact that the reimbursement policy was implemented between wave 4 and 5 and reversed between waves 5 and 6. Multivariate GEE analyses (Table 4) confirmed a significant increase between waves 4 and 5 for awareness of reimbursement possibilities (OR = 6.83, p < 0.001), awareness of medications advertisements (Beta = 0.25, p = 0.003), and awareness of other media attention about the reimbursement (Beta = 1.05, p < 0.001). The decrease between waves 5 and 6 (not shown in tables) was significant for awareness of reimbursement possibilities (OR = 0.20, p < 0.001), awareness of medications advertisements (Beta = -0.35, p < 0.001) and awareness of other media attention (Beta = -0.57, p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Percentage of smokers by income level and wave who were aware of the reimbursement possibilities, of the campaign, advertisements for cessation medications, and other media attention.

| 2010 (wave 4) | 2011 (wave 5) | 2012 (wave 6) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of reimbursement possibilities (% yes) | n = 1,912 | n = 1,971 | n = 1,919 |

| Low income level | 9.8 | 44.3 | 13.8 |

| Medium income level | 11.0 | 45.8 | 14.2 |

| High income level | 16.1 | 40.6 | 17.2 |

| Total group | 11.2 | 41.8 | 13.4 |

| Awareness of the campaign about the reimbursement policya,b (mean, SD) | |||

| Low income level | - | 0.6 (0.6) | - |

| Medium income level | - | 0.6 (0.6) | - |

| High income level | - | 0.6 (0.5) | - |

| Total group | - | 0.6 (0.6) | - |

| Awareness of advertisements for cessation medicationsa (mean, SD) | |||

| Low income level | 1.1 (1.0) | 1.3 (1.0) | 0.9 (1.0) |

| Medium income level | 1.1 (0.9) | 1.4 (1.0) | 1.0 (1.0) |

| High income level | 1.2 (1.0) | 1.4 (1.0) | 1.1 (0.9) |

| Total group | 1.1 (0.9) | 1.3 (1.0) | 1.0 (1.0) |

| Awareness of (other) media attention about the reimbursement policya (mean, SD) | |||

| Low income level | 0.3 (0.7) | 1.4 (1.0) | 0.8 (0.9) |

| Medium income level | 0.4 (0.7) | 1.3 (1.0) | 0.8 (0.9) |

| High income level | 0.5 (0.7) | 1.4 (1.0) | 0.8 (0.9) |

| Total group | 0.4 (0.7) | 1.3 (1.0) | 0.8 (0.9) |

On a scale from 0 to 3.

Questions about awareness of the campaign were only asked directly after the campaign ran, in wave 5.

There were significant income differences in awareness of medications advertisements for all waves together (Table 4), but these differences were only present between respondents who did not report their income and respondents with high income. Respondents with low and medium income levels did not differ from the high income group. There were no significant interactions between income level and survey wave for any of the awareness variables (Table 4).

Associations between awareness variables and outcome measures

Multivariate logistic regression analyses (Table 5) revealed that awareness of the campaign about the reimbursement policy at wave 5 was significantly associated with more quit attempts at wave 6 (OR = 1.95, p < 0.001), but the other awareness variables were not. None of the awareness variables were significantly associated with use of behavioral counseling, use of cessation medications, and quit success among all smokers at wave 6. There were no significant interactions between awareness variables and income level.

Table 5.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses of associations between awareness variables on wave 5 with quit attempts, use of behavioral counseling, use of cessation medications, and quit success on wave 6.

| Quit attempt (n = 991)

|

Use of behavioral counseling (n = 991)

|

Use of cessation medications (n = 991)

|

Quit success (n = 991)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% confidence interval) | p-value | Odds Ratio (95% confidence interval) | p-value | Odds Ratio (95% confidence interval) | p-value | Odds Ratio (95% confidence interval) | p-value | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 1.02 (0.73 to 1.42) | 0.906 | 0.96 (0.47 to 1.97) | 0.912 | 1.07 (0.53 to 2.14) | 0.847 | 1.55 (1.03 to 2.33) | 0.037 |

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Age group | ||||||||

| 15–24 years | 1.31 (0.73 to 2.37) | 0.362 | 0.14 (0.01 to 2.50) | 0.184 | 0.94 (0.10 to 9.26) | 0.958 | 0.25 (0.10 to 0.58)* | 0.001 |

| 25–39 years | 1.10 (0.69 to 1.75) | 0.693 | 0.42 (0.13 to 1.41) | 0.163 | 4.03 (1.15 to 14.08) | 0.029 | 0.50 (0.30 to 0.84) | 0.008 |

| 40–54 years | 1.19 (0.79 to 1.80) | 0.407 | 1.23 (0.56 to 2.69) | 0.609 | 5.35 (1.69 to 16.98) | 0.004 | 0.28 (0.17 to 0.47)* | <0.001 |

| 55 years and older | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Heaviness of smoking | 1.04 (0.94 to 1.15) | 0.492 | 1.52 (1.17 to 1.97)* | 0.002 | 1.64 (1.27 to 2.12)* | <0.001 | 0.85 (0.76 to 0.96) | 0.008 |

| Income level | ||||||||

| No answer | 0.79 (0.50 to 1.24) | 0.304 | 1.19 (0.43 to 3.33) | 0.736 | 1.30 (0.48 to 3.53) | 0.602 | 0.62 (0.36 to 1.07) | 0.087 |

| Low | 0.75 (0.47 to 1.20) | 0.228 | 1.70 (0.66 to 4.33) | 0.269 | 1.10 (0.39 to 3.15) | 0.856 | 0.59 (0.34 to 1.04) | 0.068 |

| Moderate | 1.16 (0.75 to 1.81) | 0.500 | 1.09 (0.37 to 3.15) | 0.879 | 2.46 (1.00 to 6.04) | 0.050 | 0.66 (0.38 to 1.14) | 0.134 |

| High | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Awareness of reimbursement possibilities | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.21 (0.85 to 1.72) | 0.281 | 1.63 (0.75 to 3.53) | 0.219 | 0.97 (0.47 to 1.99) | 0.929 | 1.05 (0.68 to 1.61) | 0.836 |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Awareness of the campaign about the reimbursement policy | 1.95 (1.40 to 2.71)* | <0.001 | 1.93 (1.00 to 3.74) | 0.051 | 1.35 (0.69 to 2.65) | 0.376 | 1.78 (1.17 to 2.73) | 0.008 |

| Awareness of advertisements for cessation medications | 0.92 (0.76 to 1.11) | 0.388 | 1.00 (0.66 to 1.49) | 0.987 | 1.06 (0.71 to 1.57) | 0.773 | 0.72 (0.57 to 0.91) | 0.006 |

| Awareness of (other) media attention about the reimbursement policy | 0.94 (0.76 to 1.15) | 0.553 | 1.08 (0.69 to 1.71) | 0.734 | 0.90 (0.59 to 1.36) | 0.615 | 0.88 (0.68 to 1.13) | 0.317 |

To adjust for multiple comparisons, estimates are considered significant when the p-value is below 0.004.

In an additional analysis (not shown in tables), we repeated the analysis for quit success and added use of behavioral counseling and use of cessation medications in the past 6 months at wave 6 as predictors in the model. Use of behavioral counseling was not significantly associated with quit success (OR = 0.67, p = 0.577), but use of cessation medications was (OR = 5.49, p < 0.001). Other results remained the same.

DISCUSSION

The Netherlands implemented a national reimbursement policy for smoking cessation treatment in 2011. In this paper, we examined possible income differences in the impact of the reimbursement policy and the accompanying media attention.

The first research question was whether there were changes in quit attempts, use of behavioral counseling, use of cessation medications, and quit success through time. Significant increases in quit attempts and quit success were found in the first half year that the policy was in place. Previous research conducted under controlled conditions found that reimbursing smokers for their use of cessation treatment increased the use of treatment (Reda et al. 2012). In the current real-world study, an increase in use of counseling and medication could not be demonstrated in the first half year that the policy was in place. This is similar to what we found in an earlier study among Dutch smokers that also only examined the first half year (Nagelhout et al. in press). However, other Dutch studies that examined the whole year that the policy was in place, found large increases in calls to the national quitline (Willemsen et al. 2013) and in the number of prescriptions for smoking cessation medications (Verbiest et al. 2013) in the second half of 2011. This can be explained by the fact that smokers may have waited with using smoking cessation treatment until the second half of the year, when they knew they had already spend the mandatory deductible for their health care costs of that year.

The second research question was whether there were changes in awareness of reimbursement possibilities and awareness of media attention about the reimbursement through time. Awareness of reimbursement possibilities increased between the first and second survey and decreased again between the second and third survey. This corresponds with the fact that the reimbursement policy was implemented between the first and second survey and reversed between the second and third survey.

The third research question was whether awareness of reimbursement possibilities and awareness of media attention about the reimbursement was associated with quit attempts, use of behavioral counseling, use of cessation medications, and quit success. Only awareness of the media campaign was associated with more quit attempts at the follow-up survey. Our findings thus suggest that the media campaign about the reimbursement was responsible for some of the increase in smoking cessation attempts. The campaign message was that it is possible to ‘really’ quit smoking if you use cessation treatment and that this is now reimbursed. It is possible that this positive message has, for example, increased smokers’ self-efficacy expectations or their perception of social support. Interesting is that our results imply that the Dutch media campaign had a long-term impact on smoking cessation attempts, while the campaign lasted only a few months.

The fourth research question was whether the findings from the first three research questions differed for low, medium, and high income smokers. We did not find income differences in our study, which is in contrast with beliefs suggesting that a reimbursement policy may be more effective among smokers with lower income levels (Giskes et al. 2007). A possible explanation is that smoking cessation treatment was only reimbursed after smokers completed their mandatory deductible of 170 Euro per year for any health care costs. Therefore, the treatment was not truly free of charge, which may have been a barrier especially for low income smokers. Also notable is that there appeared to be no income differences in the association between awareness of the media campaign and quit attempts. A recent review about smoking cessation media campaigns reported that there is some evidence that campaigns about how to quit smoking may increase socioeconomic inequalities in smoking (Durkin et al. 2012). However, this was not found in our study.

Limitations

In this study, we did not have a control region where the policy was not implemented. Changes in outcome measures could thus also have been caused by influences other than the policy or the media attention. Another limitation of our study was that respondents lost to follow-up between survey waves were younger, more likely to be female, higher educated, and more likely to be a heavier smokers than respondents who participated in the follow-up surveys. This could mean that our results are not fully generalizable to the population of Dutch smokers. Also, quit success is measured by asking those who attempted to quit smoking whether they are back to smoking or still stopped in the ITC Surveys (Hyland et al. 2006). Some of these respondents may turn out not to be successful in quitting smoking after the survey. It should also be noted that our findings may have been different if the surveys had been conducted at a later time in the year. Finally, we examined income differences in the impact of the policy because the price of cessation treatment may be a barrier especially for low income smokers. Income is often used as an indicator of socioeconomic status (SES) (Schaap and Kunst, 2009), but other indicators of SES were not taken into account in this study. Also, more than a quarter of respondents did not report their income. In sensitivity analyses, we found that our findings were very similar when using education instead of income in the analyses.

Conclusion

This study aimed to examine possible income differences in the impact of the national reimbursement policy for smoking cessation treatment and accompanying media attention in the Netherlands. An increase in attempts to quit smoking and quit success was found after the implementation of the reimbursement policy. Our findings suggest that the media campaign about the reimbursement policy was responsible for some of the increase in quit attempts. No change in use of behavioral counseling and medications was found. These findings are all similar to what was found in another study that examined the Dutch reimbursement policy with a different dataset (Nagelhout et al. in press). A new finding is that the Dutch reimbursement policy with accompanying media attention did not seem to decrease income inequalities in smoking. However, because it also did not seem to have increased inequalities and it did increase smoking cessation, we recommend implementing reimbursement policies together with media campaigns that stimulate quitting.

Acknowledgments

ROLE OF FUNDING SOURCE

The ITC Netherlands surveys were supported by grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw). Geoffrey Fong is supported by a Senior Investigator Award from the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research and a Prevention Scientist Award from the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute. The SILNE Project is funded by the European Commission through FP7 HEALTH-F3-2011-278273. The funders had no involvement in the design of the study, the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, the writing of the paper, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Several members of the ITC Project team at the University of Waterloo have assisted in all stages of conducting the ITC Netherlands surveys, which we gratefully acknowledge. In particular, we thank Thomas Agar, Project Manager of ITC Europe, and Mary Thompson and Christian Boudreau for their advice on the statistical analyses presented in this paper. This paper is a deliverable within the SILNE Project ‘Tackling socio-economic inequalities in smoking: Learning from natural experiments by time trend analyses and cross-national comparisons’.

Footnotes

CONTRIBUTORS

GEN conducted the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. She is the guarantor of the paper. KH managed the literature search and summarized previous related work. MCW and BvdP contributed to the design of the study and to the statistical analyses. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict declared.

References

- Ballinger GA. Using generalized estimating equations for longitudinal data analysis. Organ Res Methods. 2004;7:127–150. [Google Scholar]

- Bauld L, Judge K, Platt S. Assessing the impact of smoking cessation services on reducing health inequalities in England: Observational study. Tob Control. 2007;16:400–404. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.021626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland J, Altman D. Multiple significance tests: The Bonferroni method. BMJ. 1995;310:170. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6973.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland R, Li L, Driezen P, Wilson N, Hammond D, Thompson ME, Fong GT, Mons U, Willemsen MC, McNeill A, Thrasher JF, Cummings KM. Cessation assistance reported by smokers in 15 countries participating in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) policy evaluation surveys. Addiction. 2012;107:197–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03636.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkin S, Brennan E, Wakefield M. Mass media campaigns to promote smoking cessation among adults: An integrative review. Tob Control. 2012;21:127–138. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fix BV, Hyland A, Rivard C, McNeill A, Fong GT, Borland R, Hammond D, Cummings KM. Usage patterns of stop smoking medications in Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States: Findings from the 2006–2008 International Tobacco Control (ITC) four country survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8:222–233. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8010222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giskes K, Kunst AE, Ariza C, Benach J, Borrell C, Helmert U, Judge K, Lahemla E, Moussa K, Ostergren PO, Patja K, Platt S, Prattala R, Willemsen MC, Mackenbach JP. Applying an equity lens to tobacco-control policies and their uptake in six Western-European countries. J Public Health Policy. 2007;28:261–280. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross B, Brose L, Schumann A, Ulbricht S, Meyer C, Volzke H, Rumpf H-J, John U. Reasons for not using smoking cessation aids. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:129. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann-Boyce J, Stead LF, Cahill K, Lancaster T. Efficacy of interventions to combat tobacco addiction: Cochrane update of 2012 reviews. Addiction. 2013;108:1711–1721. doi: 10.1111/add.12291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Rickert W, Robinson J. Measuring the Heaviness of Smoking: Using self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. Br J Addict. 1989;84:791–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland A, Borland R, Li Q, Yong H-H, McNeill A, Fong GT, O’Connor RJ, Cummings KM. Individual-level predictors of cessation behaviours among participants in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl 3):83–94. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITC Project. Technical Report. Waterloo, Ontario, Canada: 2009. ITC Netherlands Survey Waves 1–3 (2008–2009) Available online at http://itc.media-doc.com/files/Report_Publications/Technical_Report/nl_w13_techreport_july62010rev.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Jin JM. PhD dissertation. University of Iowa; 2011. Working correlation selection in generalized estimating equations. [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Borland R, Hyland A, McKee SA, Thompson ME, Cummings KM. Alcohol consumption and quitting smoking in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;100:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray RL, McNeill A. Reducing the social gradient in smoking: Initiatives in the United Kingdom. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2012;31:693–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagelhout GE, De Korte-de Boer D, Kunst AE, Van der Meer R, De Vries H, Van Gelder B, Willemsen MC. Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in smoking prevalence, consumption, initiation, and cessation between 2001 and 2008 in the Netherlands. Findings from a national population survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:303. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagelhout GE, De Vries H, Fong GT, Candel MJJM, Thrasher JF, Van den Putte B, Thompson ME, Cummings KM, Willemsen MC. Pathways of change explaining the effect of smoke-free legislation on smoking cessation in the Netherlands. An application of the International Tobacco Control Conceptual Model. Nic Tob Res. 2012;14:1474–1482. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagelhout GE, Willemsen MC, Thompson ME, Fong GT, Van den Putte B, De Vries H. Is web interviewing a good alternative to telephone interviewing? Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Netherlands Survey. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:351. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagelhout GE, Willemsen MC, Van den Putte B, De Vries H, Willems RA, Segaar D. Effectiveness of a national reimbursement policy and accompanying media attention on use of cessation treatment and on smoking cessation: A real-world study in the Netherlands. Tobacco Control. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051430. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reda AA, Kotz D, Evers SMAA, Van Schayck CP. Healthcare financing systems for increasing the use of tobacco dependence treatment. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;6:Art. No.: CD004305. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004305.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaap MM, Kunst AE. Monitoring of socio-economic inequalities in smoking: Learning from the experiences of recent scientific studies. Public Health. 2009;123:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Brockwell SE, Pillitteri JL, Gitchell JG. Individual differences in adoption of treatment for smoking cessation: Demographic and smoking history characteristics. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siahpush M, McNeill A, Borland R, Fong GT. Socioeconomic variations in nicotine dependence, self-efficacy, and intention to quit across four countries: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl 3):71–75. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson ME, Fong GT, Hammond DT, Boudreau C, Driezen P, Hyland A, Borland R, Cummings KM, Hastings GB, Siahpush M, Mackintosh A, Laux F. Methods of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl 3):12–18. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay M, Payette Y, Montreuil A. Use and reimbursement costs of smoking cessation medication under the Quebec public drug insurance plan. Can J Public Health. 2009;100:417–420. doi: 10.1007/BF03404336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDHHS. How tobacco smoke causes disease: The biology and behavioral basis for smoking-attributable disease: A report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbiest MEA, Chavannes NH, Crone MR, Nielen MMJ, Segaar D, Korevaar JC, Assendelft WJJ. An increase in primary care prescriptions of stop-smoking medication as a result of health insurance coverage in the Netherlands: Population based study. Addiction. 2013;108:2183–2192. doi: 10.1111/add.12289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R, May S, West M, Croghan E, McEwen A. Performance of English stop smoking services in first 10 years: Analysis of service monitoring data. BMJ. 2013;347:f4921. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems RA, Willemsen MC, Nagelhout GE, De Vries H. Understanding smokers’ motivations to use evidence-based smoking cessation aids. Nic Tob Res. 2013;15:167–176. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems RA, Willemsen MC, Nagelhout GE, Smit ES, Janssen E, Van den Putte B, De Vries H. Evaluatie van de ‘Echt stoppen met roken kan met de juiste hulp’ campagne [Evaluation of the ‘Really quitting smoking can be done with the right help’ campaign] Maastricht University; Maastricht: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Willemsen MC, Segaar D, Van Schayck CP. Population impact of reimbursement for smoking cessation: A natural experiment in the Netherlands. Addiction. 2013;108:602–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]