Abstract

BACKGROUND:

We sought to investigate the degree to which cognitive skills explain associations between health literacy and asthma-related medication use among older adults with asthma.

METHODS:

Patients aged ≥ 60 years receiving care at eight outpatient clinics (primary care, geriatrics, pulmonology, allergy, and immunology) in New York, New York, and Chicago, Illinois, were recruited to participate in structured, in-person interviews as part of the Asthma Beliefs and Literacy in the Elderly (ABLE) study (n = 425). Behaviors related to medication use were investigated, including adherence to prescribed regimens, metered-dose inhaler (MDI) technique, and dry powder inhaler (DPI) technique. Health literacy was measured using the Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults. Cognitive function was assessed in terms of fluid (working memory, processing speed, executive function) and crystallized (verbal) ability.

RESULTS:

The mean age of participants was 68 years; 40% were Hispanic and 30% non-Hispanic black. More than one-third (38%) were adherent to their controller medication, 53% demonstrated proper DPI technique, and 38% demonstrated correct MDI technique. In multivariable analyses, limited literacy was associated with poorer adherence to controller medication (OR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.29-4.08) and incorrect DPI (OR, 3.51; 95% CI, 1.81-6.83) and MDI (OR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.01-2.65) techniques. Fluid and crystallized abilities were independently associated with medication behaviors. However, when fluid abilities were added to the model, literacy associations were reduced.

CONCLUSIONS:

Among older patients with asthma, interventions to promote proper medication use should simplify tasks and patient roles to overcome cognitive load and suboptimal performance in self-care.

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways that requires careful attention to self-care behaviors.1 Inconsistent management can increase symptom severity, leading to adverse outcomes such as preventable exacerbations, hospitalizations, and death.2‐5 Self-management involves the consistent and proper use of daily antiinflammatory controller medications. Less than 60% of patients with asthma adhere to their inhaled corticosteroid regimens,6‐8 and among older patients with asthma, only 9% to 38% consistently use them.9,10 Moreover, when patients with asthma do use their inhaled medications, they often administer the medicine incorrectly due to poor metered-dose and diskus inhaler techniques.11,12

A small body of literature has linked limited health literacy to worse asthma self-care behaviors and worse asthma outcomes.8‐10,13,14 Health literacy is defined as the “degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions”15 and is commonly measured as reading and numeracy. In the past decade, there has been an influx of health literacy interventions, some tailored for patients with asthma.12,16 However, a poor understanding of the underlying components of health literacy has limited the effectiveness of tested strategies, and asthma disparities by health literacy persist.17,18 Additional research is warranted to better understand the mechanisms through which health literacy affects asthma outcomes.

Research has documented associations between health literacy and limited cognitive abilities and has shown that cognitive ability may mediate the relationship between health literacy and health outcomes.19‐23 In a sample of older US adults, Wolf et al24 found that cognitive abilities explain the relationship between health literacy and performance on a range of hypothetical health tasks. These studies highlight the importance of considering cognitive function when seeking to ease the burden of health-care tasks. However, confirmatory analyses are needed among patients performing actual self-management behaviors. The objective of the present study was to investigate the degree to which cognitive skills explain the association between health literacy and asthma medication-related behaviors performed by older patients with asthma.

Materials and Methods

Settings and Participants

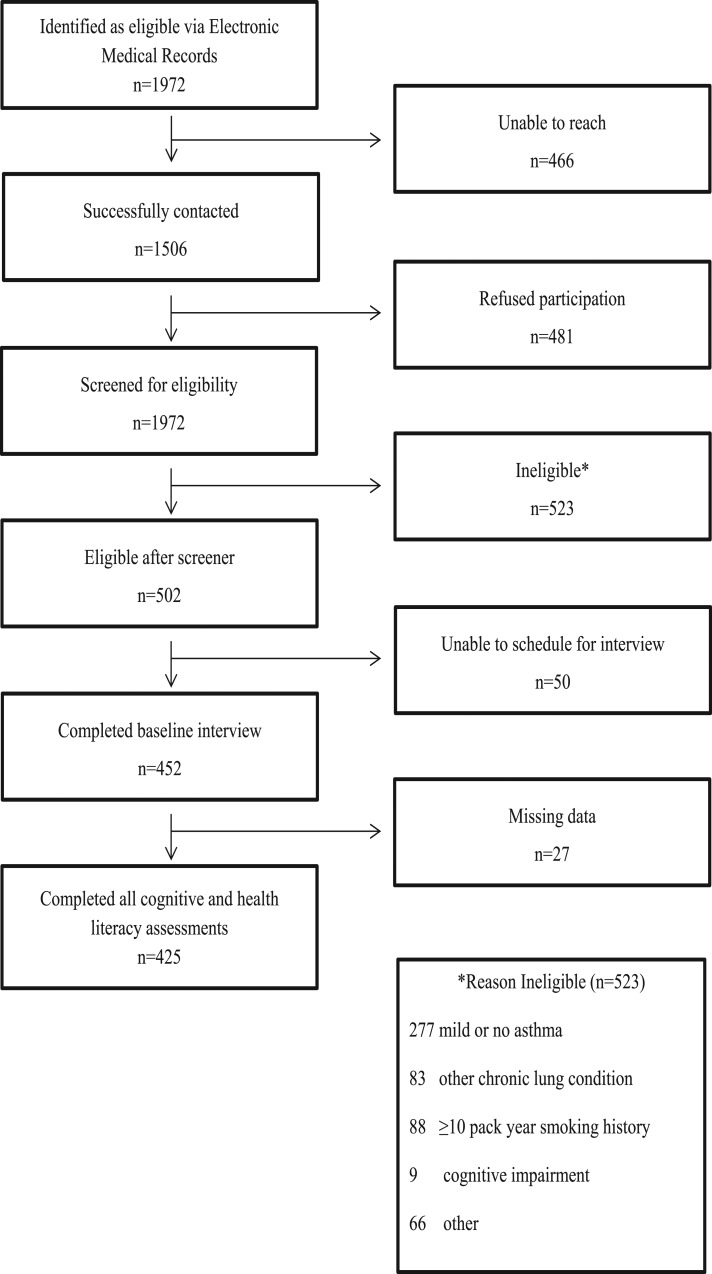

This study used baseline data from the Asthma Beliefs and Literacy in the Elderly (ABLE) study. ABLE is a prospective cohort study of patients with asthma aged ≥ 60 years. Participants were recruited from eight outpatient clinics (primary care, geriatrics, pulmonology, allergy, and immunology) in New York City, New York, and Chicago, Illinois, from December 2009 through May 2012. A full description of the systematic recruitment procedures are published elsewhere.10,14 In brief, we identified 1,972 patients; successfully contacted 1,506; and consented and screened 1,025, of whom 502 were eligible. Of these, 452 completed the baseline interview (Fig 1). All participants provided written consent. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Lutheran Medical Center, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, and Mercy Hospital and Medical Center (e-Appendix 1 (68.7KB, pdf) ).

Figure 1 –

Participant flowchart.

Patients were eligible to participate if they (1) were aged ≥ 60 years; (2) spoke English or Spanish; and (3) had moderate or severe persistent asthma as defined by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Expert Panel on Asthma.1 We excluded individuals with a chart-documented or self-reported diagnosis of COPD or other chronic respiratory illness and those with a self-reported smoking history of ≥ 10 pack-years because they are at increased risk of COPD.

Measures

The primary variables of interest for this study were health literacy; cognitive abilities; and medication-related behaviors, including adherence to prescribed asthma medications and device usage in terms of proper inhaler technique (metered dose or dry powder).

Medication Adherence:

Adherence to asthma controller medications (inhaled corticosteroids and leukotriene receptor inhibitors) was assessed through self-report with the Medication Adherence Reporting Scale (MARS). The MARS is a validated, 10-item measure designed to minimize social desirability bias. It was previously adapted to assess adherence with asthma medications and is correlated with an objective electronic adherence measure.25 Each item is rated on a five-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater adherence. Participants with a MARS score of ≥ 4.5 were classified as having good adherence to controller medications.26,27

Inhaler Technique:

Patients’ ability to administer their asthma controller medication therapies was assessed using a standardized checklist of steps in the proper use of a metered-dose inhaler (MDI) and a dry powder inhaler (DPI). The MDI and DPI assessments address eight and seven steps in the use of the devices, respectively, covering the essential elements of use from preparation of the devices to their actuation and delivery of medications.28‐30 During the interview, the participants were asked to demonstrate use of the placebo devices. The MDI was administered to the entire sample regardless of their current asthma medication use, whereas the DPI was administered only to those who reported having a prescription for a DPI. Trained interviewers observed the patients and documented the number of steps completed correctly. A threshold of > 75% correctly completed steps was set to define adequate inhaler technique.

Health Literacy:

Health literacy was measured using the Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (S-TOFHLA).31 The S-TOFHLA is composed of a reading comprehension section and a numeracy exercise. The reading comprehension section includes 36 items that use the cloze procedure where every fifth and seventh word in the passage is omitted and four multiple choice options are provided. The numeracy section includes four items that assess the patient’s ability to read and interpret information typically encountered in a health-care setting. Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating higher health literacy. We dichotomized health literacy as adequate (score ≥ 67) and limited (score < 67). Before conducting the analyses, the research team examined the distribution of the S-TOFHLA scores and determined that few patients scored in the lowest categories. We, therefore, combined the marginal and low literacy groups.10,14,32 The S-TOFHLA has been validated for use in both English and Spanish.33

Cognitive Abilities:

Table 1 presents a summary of the study cognitive battery.34‐37 A mixture of pen-and-paper tasks and interviewer-administered cognitive tests were used. Reading and numeracy skills within these tasks were limited. Interviewers were trained to administer the cognitive battery, and they needed to pass a certification test before undertaking participant interviews. Study staff convened regular meetings to ensure accurate scoring of each assessment.

TABLE 1 ] .

Description of Cognitive Measures

| Trait | Measure | Source | Description |

| Processing speed | Pattern comparison | Salthouse and Babcock34 | Compare pairs of simple line drawings that are the same or different, completing as many trials as one can in a given time period. |

| Working memory | WMS letter-number sequencing | Wechsler35 | Listen to increasingly longer series of numbers and letters, rearrange the information, and repeat it as numbers from least to greatest and letters in alphabetical order. |

| Long-term memory | WMS II story A | Wechsler35 | Read a short story and repeat as much of the story as possible after an approximately 25-min delay. |

| Executive function | Trails A & B | Spreen and Strauss36 | Connect dots on a page scattered with numbers (Trails A) or both numbers and letters (Trails B) in the appropriate sequence. |

| Global cognitive function | Mini-mental state examination | Folstein et al37 | Global measure of cognition that is commonly used in medical settings. |

| Verbal fluency | Animal naming test | Spreen and Strauss36 | Name as many animals of any kind in 1 min. |

Trails A & B = Trail Making Test parts A and B; WMS = Wechsler Memory Scale.

Cognitive abilities were broadly classified as fluid (processing speed, working memory, long-term memory, executive function, and global cognitive function) or crystallized (verbal) ability. Fluid abilities refer to cognitive traits associated with active information processing in which prior knowledge is of relatively little help. A latent trait for fluid ability was derived from these tests.24 Crystallized ability refers to stored information in long-term memory, or general background knowledge, and was measured using the animal naming task. Animal naming is a measure of verbal fluency, which loads highly as a factor of crystallized ability.38

Statistical Analysis

For these analyses, we excluded participants with incomplete cognitive function and health literacy data, resulting in a sample of 425 participants (94%). Descriptive statistics were calculated for each variable. Pearson product moment correlations were used to examine associations between health literacy and cognitive tests. A factor score for fluid ability was created to reduce cognitive skills to one measure and to avoid multicollinearity in subsequent regression models. The factor score was created by forcing a single factor score with maximum likelihood estimation. Crystallized ability was assessed using a single measure, animal naming.

Multivariable logistic regression modeling was conducted to examine the independent associations between health literacy and fluid and crystallized abilities with medication-related behaviors. Self-reported age, sex, race/ethnicity, number of comorbid chronic conditions, and number of years since asthma diagnosis were included in all models as covariates. The final model included all three variables and examined the extent to which the effect of health literacy was attenuated by cognitive abilities. All analyses were performed using Stata 12.1 (StataCorp LP) statistical software.

Results

A descriptive summary of study participant characteristics is provided in Table 2. Overall, the mean age of the sample was 67.4 ± 6.8 years. The majority of patients were women (83.5%), nonwhite (Hispanic, 38.1%; non-Hispanic black, 30.8%), and one-half (50.5%) had a high school education or less. Nearly one-fourth (23.0%) preferred speaking Spanish. Individuals had, on average, five chronic conditions (mean, 4.8 ± 2.1). The average length of time with asthma was 31.4 years, and the majority (79.3%) used an asthma controller medication. Approximately one-third (36.1%) had limited health literacy skills.

TABLE 2 ] .

Characteristics of Sample (N = 425)

| Variable | Summary Value |

| Age | 67.4 ± 6.8 |

| Female sex | 83.5 |

| Race | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 30.8 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 22.1 |

| Hispanic | 38.1 |

| Other | 9.0 |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 32.8 |

| High school graduate | 17.7 |

| Some college | 20.2 |

| College graduate | 29.3 |

| Income < $1,350/mo | 53.7 |

| Limited health literacy | 35.8 |

| Number of chronic conditions | 4.8 ± 2.1 |

| Years with asthma | 31.4 ± 20.7 |

| Asthma controller medication use | |

| Any controller medication usea | 79.3 |

| Inhaled corticosteroid use | 73.2 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD or %.

Includes patients taking at least one of the following classes of asthma medications: inhaled corticosteroids, leukotriene inhibitors, long-acting β-adrenergic receptor agonists, and other miscellaneous controller medications, such as theophylline, cromolyn sodium, and prednisone.

The average mini-mental status examination score was 26.0 ± 3.5 of 30 points. Using age and education population-based norms, 27.1% were classified as having cognitive impairment according to their mini-mental status examination score. On average, participants completed 6.5 ± 3.6 of 21 Wechsler Memory Scale Letter-Number Sequencing items and 10.3 ± 4.0 of 30 Pattern Comparison Test items and recalled 8.2 ± 4.5 of 25 Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale story delayed-recall items. Participants took an average of 62.6 ± 34.8 s to complete the Trail Making Test part A and 191.9 ± 96.1 s to complete part B. The average number of animals recalled in 1 min was 15.7 ± 5.5. Health literacy was correlated with all cognitive measures. Fluid abilities were strongly correlated with health literacy (r = 0.84, P < .001), whereas crystallized abilities were moderately correlated (r = 0.51, P < .001).

Only 38.2% of participants were adherent to their asthma controller medication. Additionally, 52.6% demonstrated proper DPI technique, whereas one-third (37.6%) demonstrated correct MDI technique. Compared with participants with adequate health literacy, individuals with limited health literacy were significantly less likely to adhere to their controller medication (22.5% vs 46.4%, P < .001) and demonstrate correct DPI technique (28.7% vs 42.8%, P = .004) and correct MDI technique (35.9% vs 66.4%, P < .001).

In multivariable models, adequate health literacy was a significant independent predictor of adherence to controller medication (OR, 2.30; 95% CI, 1.29-4.08), correct DPI technique (OR, 3.51; 95% CI, 1.81-6.83), and correct MDI technique (OR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.01-2.65) (Table 3). Similarly, fluid ability was significantly associated with adherence (OR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.30-2.75), DPI technique (OR, 2.52; 95% CI, 1.59-3.98), and MDI technique (OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.15-2.14). Crystallized ability was a significant independent predictor of adherence to controller medication (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.00-1.10) and DPI technique (OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.08-1.26) but not MDI technique (OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.99-1.07).

TABLE 3 ] .

Multivariable Models of Health Literacy, Cognitive Abilities, and Asthma Self-Management Behaviors

| Equation and Variable | HL | FA | CA | HL + FA | HL + CA | HL + CA + FA |

| Adherent to asthma controller | ||||||

| Adequate HL | 2.30a (1.29-4.08) | … | … | 1.45 (0.70-2.98) | 2.06b (1.13-3.76) | 1.44 (0.70-2.97) |

| FA | … | 1.89c (1.30-2.75) | … | 1.63b (1.02-2.62) | … | 1.57 (0.94-2.60) |

| CA | … | … | 1.05b (1.00-1.10) | … | 1.03 (0.98-1.08) | 1.01 (0.96-1.07) |

| DPI > 75% steps correct | ||||||

| Adequate HL | 3.51c (1.81-6.83) | … | … | 1.89 (0.82-4.39) | 2.52a (1.26-5.07) | 1.95 (0.83-4.60) |

| FA | … | 2.52c (1.59-3.98) | … | 1.94b (1.10-3.42) | … | 1.37 (0.74-2.55) |

| CA | … | … | 1.17c (1.08-1.26) | … | 1.14a (1.05-1.23) | 1.12a (1.03-1.22) |

| MDI > 75% steps correct | ||||||

| Adequate HL | 1.64b (1.01-2.65) | … | … | 1.09 (0.59-2.02) | 1.55 (0.94-2.57) | 1.09 (0.59-2.02) |

| FA | … | 1.57a (1.15-2.14) | … | 1.52b (1.02-2.24) | … | 1.54b (1.00-2.37) |

| CA | … | … | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) | … | 1.02 (0.97-1.06) | 1.00 (0.95-1.04) |

Data are presented as OR (95% CI). All models are controlled for age, sex, race/ethnicity, number of chronic conditions, and number of years since asthma diagnosis. CA = crystallized ability; DPI = dry power inhaler; FA = fluid ability; HL = health literacy; MDI = metered-dose inhaler.

P < .01.

P < .05.

P < .001.

The addition of fluid ability to the model that included health literacy reduced the magnitude of the association between health literacy and all outcomes (Table 3). The relationship between health literacy and medication adherence was attenuated by 37% and was no longer statistically significant (OR, 1.45; 95% CI, 0.70-2.98). Similar changes were observed for DPI technique (46% attenuation; OR, 1.89; 95% CI, 0.82-4.39) and MDI technique (34% attenuation; OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.59-2.02). Fluid abilities remained an independent predictor of adherence (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.02-2.62), DPI technique (OR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.10-3.42), and MDI technique (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.02-2.24).

Crystallized ability also attenuated the association of health literacy with adherence and inhaler technique (Table 3). In these models, health literacy maintained its significant association with adherence and MDI technique but not with DPI technique. Additionally, crystallized ability remained an independent predictor of DPI technique (OR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.05-1.23) but not of adherence (OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.98-1.08) or MDI technique (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.97-1.06).

The inclusion of both fluid and crystallized abilities in the multivariable models rendered the associations of health literacy with adherence and inhaler technique not statistically significant. In these models, fluid ability remained an independent predictor of MDI technique (OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.00-2.37) but not adherence (OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 0.94-2.60) or DPI technique (OR, 1.37; 95% CI, 0.74-2.55). Crystallized ability remained an independent predictor of DPI technique (OR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.03-1.22) but not adherence (OR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.96-1.07) or MDI technique (OR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.95-1.04).

Discussion

In this study of older adult patients with asthma, fluid abilities were strongly related to health literacy and explained a large portion of the relationship between health literacy and asthma medication behaviors. This is not surprising when considering the tasks faced by older patients with asthma to manage their health condition. Asthma medication behaviors include recall of physicians’ instructions, the use of multiple devices, understanding when to use each type of device (maintenance vs emergency), and following a range of steps in an action plan. Although reading and numeracy are involved in all of these activities, these tasks rely on many other components of cognition too, including memory, reasoning, and the ability to multitask and avoid distraction.

Fluid abilities that reflect one’s aptitude to actively learn new concepts and procedures were independently associated with both MDI and DPI techniques and attenuated health literacy associations with both outcomes. Crystallized abilities that capture one’s background knowledge and prior experience were independently associated with DPI but not MDI technique and only moderately attenuated the association of health literacy with DPI outcome. This discordance between DPI and MDI technique is likely to be a spurious finding possibly attributed to the greater percentage of participants able to correctly complete the DPI technique (53%) vs the MDI technique (38%). Administering an MDI involves greater physical coordination and dexterity than a DPI, which may be more challenging for elderly patients with asthma.39,40 Our models did not consider physical function as an explanatory factor, but future research considering the impact of physical function may help to explain the discrepancies in these findings. Regardless, the stronger and more consistent findings between fluid and crystallized abilities for DPI and MDI techniques were not surprising; previous research has shown that crystallized abilities are less predictive of health performance and outcomes than fluid skills.23,24 Clinicians should continue to be mindful of their patients’ cognitive abilities when prescribing inhalers and addressing overall health.

These findings can inform clinical practice and interventions that seek to improve acquisition and retention of necessary disease and treatment-specific knowledge and skills in patients with asthma. This is especially relevant in the context of aging because fluid abilities associated with active learning processes decline with age, whereas crystallized abilities remain mostly intact.41,42 Older patients not only have to deal with cognitive decline but also multiple other chronic conditions associated with aging that require careful management.

To account for varying levels of cognitive ability, physicians should periodically confirm and correct inhaler technique as necessary during patient visits, especially among their elderly patients.1 When teaching or correcting inhaler technique, health-care professionals should be mindful that instructions for inhalers typically include several steps. Individuals generally have the capacity to process four to seven new concepts or instructions at a time.41 Devices with multiple steps (like an MDI), therefore, may always be challenging for the elderly patient. “Chunking” similar information into several small sections is a recommended practice to overcome this issue.43 For example, inhaler technique could be chunked into three sections: (1) get your inhaler READY: shake the inhaler, remove the cap, and put the open end in the spacer; (2) SET your mouth to use your inhaler: breathe out slowly and put your lips around the mouthpiece; and (3) GO: push down on the inhaler and breathe in slowly.16,44 To further promote inhaler technique, a goal of industry and human factors research should be to eliminate unnecessary steps by designing easier-to-use inhalers.

An additional communication strategy could include the teach-to-goal technique, which teaches patients self-care skills, repeating as necessary until they reach desired behaviors.45 Press et al46 found that a brief teach-to-goal intervention on MDI and DPI technique reduced misuse of the inhaler. An example teach-to-goal encounter to promote inhaler technique could involve first a health-care provider demonstrating correct use of the device followed by an assessment of the patient’s technique. This cycle would be repeated until the patient demonstrated all steps correctly.46 While communicating with patients, health-care providers should be mindful to limit the amount of information provided in one educational session. This can create layers of information that offer what educational researchers refer to as “scaffolds,” which are highly beneficial in practically every learning situation.47,48

Broadly, the present findings are directly aligned with other studies that support the idea that health literacy encompasses a vast range of capabilities, spanning one’s ability to learn, retain, and actively apply information pertinent to his or her health.20,23,24,49 Health literacy measures that solely focus on reading and numeracy fail to capture the additional cognitive factors required for patients to manage their health. Researchers should continue to refine health literacy’s conceptual model by incorporating cognitive measures within research protocols.

This study had limitations. The findings may not be generalizable to younger patients with asthma or patients residing outside urban areas. We also recognize that these analyses are specific to asthma medication behaviors, and older adults often manage complex medication regimens for multiple comorbidities. The effects of cognitive abilities may be more pronounced among patients managing multiple chronic conditions. Additionally, the self-reported outcome data may be subject to social desirability bias. These were also cross-sectional data, limiting the ability to make statements about causality. Adherence was measured using a common, although general self-report assessment. Inhaler technique was only observed once by one interviewer, and thus, we were unable to assess interrater reliability and test-retest reliability. Clinical outcomes were also not examined in this investigation.

In conclusion, accounting for cognition sharply reduces the association of health literacy with asthma medication self-management among older adults. This observation supports a growing body of evidence that cognition explains the impact of health literacy on health behaviors and needs to be more carefully considered in interventions designed to improve illness self-management. Interventions that seek to improve asthma self-care behaviors among older patients with asthma should seek to decrease the cognitive burden of many tasks. This can be done by deconstructing the behaviors patients with asthma are asked to perform and seeking solutions that simplify these unnecessarily complex tasks.

Supplementary Material

Online Supplement

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: R. O. had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. R. O. contributed to the data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content, and final approval of the manuscript; M. S. W., M. S., J. P. W., and A. D. F. contributed to the study design, data analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content, and final approval of the manuscript; S. G. S. contributed to the data analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content, and final approval of the manuscript; and M. M. and D. P. V. contributed to the data acquisition, critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content, and final approval of the manuscript.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following conflicts of interest: Dr Sano is a consultant for Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, sanofi-aventis US LLC, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Medpace, and Targacept Inc Company. Dr Wisnivesky is a member of the research board of EHE International; has received consulting fees from Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp, UBS, and IMS Health Incorporated; and was awarded a research grant from GlaxoSmithKline plc to conduct a COPD study. Mss O’Conor and Martynenko and Drs Wolf, Smith, Vicencio, and Federman have reported that no potential conflicts of interest exist with any companies/organizations whose products or services may be discussed in this article.

Role of sponsors: The sponsors had no role in the design of the study, the collection of data, the data analysis, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Additional information: The e-Appendix can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

ABBREVIATIONS

- DPI

dry powder inhaler

- MARS

Medication Adherence Reporting Scale

- MDI

metered-dose inhaler

- S-TOFHLA

Short Test of Functional Health Literacy Assessment

Footnotes

FOR EDITORIAL COMMENT SEE PAGE 1204

Part of this article was presented in abstract form at the 5th Annual Health Literacy Research Conference, October 28-29, 2013, Washington, DC.

FUNDING/SUPPORT: Funding was provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [5R01HL096612-04].

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians. See online for more details.

References

- 1.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert panel report 3 (EPR-3): guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma-summary report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(suppl 5):S94-S138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ordoñez GA, Phelan PD, Olinsky A, Robertson CF. Preventable factors in hospital admissions for asthma. Arch Dis Child. 1998;78(2):143-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dales RE, Kerr PE, Schweitzer I, Reesor K, Gougeon L, Dickinson G. Asthma management preceding an emergency department visit. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152(10):2041-2044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dales RE, Schweitzer I, Kerr P, Gougeon L, Rivington R, Draper J. Risk factors for recurrent emergency department visits for asthma. Thorax. 1995;50(5):520-524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halterman JS, Aligne CA, Auinger P, McBride JT, Szilagyi PG. Inadequate therapy for asthma among children in the United States. Pediatrics. 2000;105(1 pt 3)(suppl 2):272-276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Apter AJ, Reisine ST, Affleck G, Barrows E, ZuWallack RL. Adherence with twice-daily dosing of inhaled steroids. Socioeconomic and health-belief differences. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(6):1810-1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Apter AJ, Boston RC, George M, et al. Modifiable barriers to adherence to inhaled steroids among adults with asthma: it’s not just black and white. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(6):1219-1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apter AJ, Wan F, Reisine S, et al. The association of health literacy with adherence and outcomes in moderate-severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(2):321-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bozek A, Jarzab J. Adherence to asthma therapy in elderly patients. J Asthma. 2010;47(2):162-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Federman AD, Wolf MS, Sofianou A, et al. Self-management behaviors in older adults with asthma: associations with health literacy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(5):872-879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Press VG, Arora VM, Shah LM, et al. Misuse of respiratory inhalers in hospitalized patients with asthma or COPD [published correction appears in J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(4):458]. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(6):635-642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paasche-Orlow MK, Riekert KA, Bilderback A, et al. Tailored education may reduce health literacy disparities in asthma self-management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(8):980-986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams MV, Baker DW, Honig EG, Lee TM, Nowlan A. Inadequate literacy is a barrier to asthma knowledge and self-care. Chest. 1998;114(4):1008-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Federman AD, Wolf MS, Sofianou A, et al. Asthma outcomes are poor among older adults with low health literacy. J Asthma. 2014;51(2):162-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sobel RM, Paasche-Orlow MK, Waite KR, Rittner SS, Wilson EA, Wolf MS. Asthma 1-2-3: a low literacy multimedia tool to educate African American adults about asthma. J Community Health. 2009;34(4):321-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. Health literacy interventions and outcomes: an updated systematic review. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2011;(199):1-941. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosas-Salazar C, Apter AJ, Canino G, Celedón JC. Health literacy and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(4):935-942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker DW, Wolf MS, Feinglass J, Thompson JA. Health literacy, cognitive abilities, and mortality among elderly persons. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(6):723-726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Federman AD, Sano M, Wolf MS, Siu AL, Halm EA. Health literacy and cognitive performance in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1475-1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolf MS, Wilson EAH, Rapp DN, et al. Literacy and learning in health care. Pediatrics. 2009;124(suppl 3):S275-S281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen HT, Kirk JK, Arcury TA, et al. Cognitive function is a risk for health literacy in older adults with diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;101(2):141-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serper M, Patzer RE, Curtis LM, et al. Health literacy, cognitive ability, and functional health status among older adults. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(4):1249-1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolf MS, Curtis LM, Wilson EAH, et al. Literacy, cognitive function, and health: results of the LitCog study. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1300-1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen JL, Mann DM, Wisnivesky JP, et al. Assessing the validity of self-reported medication adherence among inner-city asthmatic adults: the Medication Adherence Report Scale for Asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;103(4):325-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wisnivesky JP, Kattan M, Evans D, et al. Assessing the relationship between language proficiency and asthma morbidity among inner-city asthmatics. Med Care. 2009;47(2):243-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roy A, Lurslurchachai L, Halm EA, Li XM, Leventhal H, Wisnivesky JP. Use of herbal remedies and adherence to inhaled corticosteroids among inner-city asthmatic patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;104(2):132-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manzella BA, Brooks CM, Richards JM, Jr, Windsor RA, Soong S, Bailey WC. Assessing the use of metered dose inhalers by adults with asthma. J Asthma. 1989;26(4):223-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Interiano B, Guntupalli KK. Metered-dose inhalers. Do health care providers know what to teach? Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(1):81-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Beerendonk I, Mesters I, Mudde AN, Tan TD. Assessment of the inhalation technique in outpatients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using a metered-dose inhaler or dry powder device. J Asthma. 1998;35(3):273-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nurss JR, Parker RM, Williams MV, Baker DW. TOFHLA. Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults. Snow Camp, NC: Peppercorn Books and Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Federman AD, Wolf M, Sofianou A, et al. The association of health literacy with illness and medication beliefs among older adults with asthma. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(2):273-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nurss J. Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;38(1):33-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salthouse TA, Babcock RL. Decomposing adult age differences in working memory. Dev Psychol. 1991;27(5):763-776. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wechsler D. WMS-III: Wechsler Memory Scale Administration and Scoring Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spreen O, Strauss E. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests: Administration, Norms, and Commentary. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prince MJ, Macdonald AM, Sham PC, Richards M, Quraishi S, Horn I. The development and initial validation of a telephone-administered cognitive test battery (TACT). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1999;8(1):49-57. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gibson PG, McDonald VM, Marks GB. Asthma in older adults. Lancet. 2010;376(9743):803-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. NAEPP Working Group Report: Considerations for Diagnosing and Managing Asthma in the Elderly (NHLBI 1996). Bethesda, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; National Institutes of Health; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 1996. NIH publication 96-3662. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson EAH, Wolf MS. Working memory and the design of health materials: a cognitive factors perspective. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(3):318-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park DC, Lautenschlager G, Hedden T, Davidson NS, Smith AD, Smith PK. Models of visuospatial and verbal memory across the adult life span. Psychol Aging. 2002;17(2):299-320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching Patients With Low Literacy Skills. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott & Company; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson EA, Park DC, Curtis LM, et al. Media and memory: the efficacy of video and print materials for promoting patient education about asthma. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80(3):393-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baker DW, DeWalt DA, Schillinger D, et al. “Teach to goal”: theory and design principles of an intervention to improve heart failure self-management skills of patients with low health literacy. J Health Commun. 2011;16(suppl 3):73-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Press VG, Arora VM, Shah LM, et al. Teaching the use of respiratory inhalers to hospitalized patients with asthma or COPD: a randomized trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1317-1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Borzekowski DL. Considering children and health literacy: a theoretical approach. Pediatrics. 2009;124(suppl 3):S282-S288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gutiérrez KD, Rogoff B. Cultural ways of learning: individual traits or repertoires of practice. Educ Res. 2003;32(5):19-25. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morrow D, Clark D, Tu W, et al. Correlates of health literacy in patients with chronic heart failure. Gerontologist. 2006;46(5):669-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Online Supplement