Abstract

Phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate (PIP2) regulates the activities of many membrane proteins including ion channels through direct interactions. However, the affinity of PIP2 is so high for some channel proteins that its physiological role as a modulator has been questioned. Here we show that PIP2 is an important cofactor for activation of small conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channels (SK) by Ca2+-bound calmodulin (CaM). Removal of the endogenous PIP2 inhibits SK channels. The PIP2-binding site resides at the interface of CaM and the SK C-terminus. We further demonstrate that the affinity of PIP2 for its target proteins can be regulated by cellular signaling. Phosphorylation of CaM T79, located adjacent to the PIP2-binding site, by Casein Kinase 2 reduces the affinity of PIP2 for the CaM-SK channel complex by altering the dynamic interactions among amino acid residues surrounding the PIP2-binding site. This effect of CaM phosphorylation promotes greater channel inhibition by G-protein-mediated hydrolysis of PIP2.

Phosphatidylinositol phosphates (PIPs) are minor acidic phospholipids found in the inner leaflet of the cell plasma membrane (~1% of total phospholipid pool)1. PIPs play a vital role in cellular signaling, by their direct interaction with membrane proteins1–8. In addition, PIP metabolites, such as IP3 and diacylglycerol (DAG), are intracellular second messengers, which activate additional signaling cascades and regulate cellular activities1. Through direct interactions, PIP lipids, particularly PI(4,5)P2, regulate functions of many plasma membrane proteins, including the activities of different ion channels, such as Kv, Kir, KCNQ, and Cav1,3. However, in the field of PIP2 cell biology, an unsettled issue is that the affinity of PIP2 can be so high for some of its target proteins, given the typical levels of PIP2 in the cell plasma membrane, that the physiological role of PIP2 as a modulator has been questioned1,4,9. In such cases, it remains unclear whether cellular signaling can regulate the affinity of PIP2 for its target proteins.

Small- and intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (SK and IK) are widely expressed in excitable tissues, including the central nervous system (CNS) and the cardiovascular system10–14. They play pivotal roles in regulating membrane excitability by Ca2+. In CNS, activation of SK channels generates the afterhyperpolarization (AHP) and dampens firing of action potentials, and thus contributes to Ca2+ regulation of neuronal excitability, dendritic integration, synaptic transmission and plasticity, and learning and memory formation10,12,14–22. The functional importance of SK/IK channels is further demonstrated by their potential involvement in certain diseases23–27. In the SK channel family, four genes have been identified, KCNN1 for KCa2.1 channels (SK1), KCNN2 for KCa2.2 (SK2), KCNN3 for KCa2.3 (SK3) and KCNN4 for KCa3.1 (IK)12,14. Spliced variants exist for each of the four SK genes, such as SK2-b, which is less sensitive to Ca2+ for its activation28.

Structurally, SK channels look similar to voltage-gated K+ channels (Kv), with four subunits forming a tetramer and each subunit having six transmembrane segments (S1 – S6). However, SK channels are activated exclusively by Ca2+-bound calmodulin (CaM)29. CaM, constitutively tethered to the CaM binding domain (CaMBD) at the channel C-terminus, serves as the high-affinity Ca2+ sensor. Our recent structural data show that the channel segment (R396 – M412), which connects S6 to the CaMBD, is an intrinsically disordered fragment (IDF) that plays a unique role in coupling binding of Ca2+ to CaM and opening of SK channels30. SK channels are subjected to regulation by intracellular second messengers. Phosphorylation of CaM, when complexed with the channel, at T79 by Casein Kinase 2 (CK2) inhibits SK channels16,31–33. Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) reverses the effect of CK2. Both CK2 and PP2A interact directly with SK channels and the combined activities of CK2 and PP2A determine the phosphorylation status at T79, and thus the inhibition of SK channels31. It is not clear how phosphorylation of CaM at T79 inhibits SK channels14,16,31,32. Furthermore, it remains unknown whether SK channel activity is regulated directly by PIP2.

Here we report that PIP2 is an important cofactor for Ca2+-dependent activation of SK channels. Removal of the endogenous PIP2 results in inhibition of SK channels, and such inhibition can be reversed by application of synthetic PIP2 derivatives. Using computational and experimental tools, we have identified the PIP2-binding site, which includes amino acids from both CaM and the IDF of SK channels. We have further established that CK2 phosphorylation of CaM T79, which is located in the vicinity of the PIP2-binding site, will weaken the interaction between PIP2 and the CaM-SK channel complex by altering the dynamic interactions among amino acid residues around the PIP2 binding site. The reduced affinity of PIP2 for the CaM-SK channel complex greatly facilitates inhibition of SK channels by Gq-mediated hydrolysis of PIP2.

RESULTS

PIP2 is a cofactor for activation of SK channels by Ca2+

To test whether SK channels are regulated by PIP2, SK2-a channels (WT) together with CaM (WT) were expressed in TsA cells and their currents were recorded using inside-out membrane patches30,34. The patch membrane was exposed to Ca2+ and other reagents sequentially, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1 (Supplementary Results). SK2-a channels were activated by a bath solution containing 2 μM Ca2+, which should produce near-maximal channel open probability29,34. In the presence of 2 μM Ca2+, application of poly-lysine (poly-K), at 900 μg/ml, inhibited the SK2 currents by sequestering the endogenous PIP2 (Supplementary Fig. 1)35. The current amplitude decreased rapidly (Figs. 1a and 1b). Once the endogenous PIP2 was scavenged by poly-K, SK2 currents could not be recovered even when higher Ca2+ concentrations were applied (not shown).

Figure 1. PIP2 is an essential cofactor for activation of SK2 channels by Ca2+.

a, Representative time course of inhibition of the SK2 channel activity by depletion of the endogenous PIP2 upon application of poly-lysine (poly-K, 900 μg/ml). b, Raw current ramp traces before and after application of poly-lysine. Both traces are from the same patch in panel a (indicated by arrows). c, Restoration of the SK2 channel activity after application of exogenous diC8-PIP2 at the concentrations indicated once the endogenous PIP2 was depleted by poly-K. d, Dose-response curve of channel reactivation by exogenous diC8-PIP2 (n = 6). The bath solutions contained 2 μM Ca2+. Data in panel d represent mean values ± s.e.m.

We next tested whether inhibition of the SK currents by poly-K could be reversed by exogenous PIP2, such as the water soluble synthetic PIP2 derivative, diC8-PIP236. After inhibition of SK2-a channels by poly-K reached the steady state (Supplementary Fig. 1), increasing concentrations of diC8-PIP2 were added to the bath solution (Fig. 1c). Maximal currents were obtained at diC8-PIP2 concentrations between 30 to 100 μM (Fig. 1c). Fitting of the data to a dose-response equation yielded an EC50 of 1.9 ± 0.22 μM (n = 6, Ca2+ = 2 μM, Fig. 1d). The EC50 for activation of SK2 channels by diC8-PIP2 is several-fold higher than that for activation of GIRK channels37. Collectively, results of inhibition of SK2 by poly-K depletion of the endogenous PIP2 and subsequent restoration of the channel activity by application of the exogenous diC8-PIP2 suggested that PIP2 was required for the normal functions of SK channels.

The PIP2-binding site in the CaM-SK2 complex

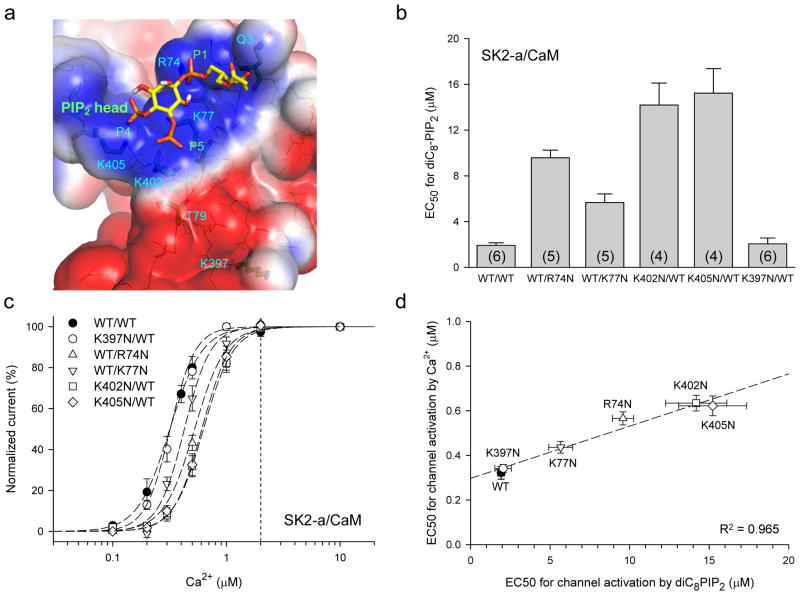

Typically, PIP2-binding sites consist of positively-charged amino acid residues and are located near the channel gating machinery1,38. Analysis of our structural model, which includes both CaM and the SK2 channel fragment30, showed the surface electrostatic potential distribution (Supplementary Fig. 2). While the protein complex surface bore primarily negative charges (red), there were two loci, near the IDF, which showed clusters of positive charges (blue). Molecular docking revealed that the PIP2 head group could fit well into these two positively charged loci, interacting with residues from both proteins, most notably the positively charged residues that interacted with the phosphate groups of PIP2, including K402 and K405 of SK2 and R74 and K77 of CaM (Fig. 2a). K402 and K405 are highly conserved among different members of the SK channel family30. To test whether the putative PIP2-binding site represented the functional PIP2-binding site, we mutated the positively charged residues predicted to interact with the PIP2 head group and examined the effects of mutations on modulation of SK channels by PIP2. K402N, K405N, R74N and K77N, all tested at 2 μM Ca2+, significantly increased the EC50 for activation of SK2 channels by diC8-PIP2 to 14.2 ± 1.93 μM (n = 4, p < 0.001), 15.2 ± 2.14 μM (n = 4, p < 0.001), 9.6 ± 0.66 μM (n = 5, p < 0.001) and 5.7 ± 0.75 μM (n = 5, p < 0.001), respectively (a 3.0 – 8.0-fold increase, Fig. 2b). In contrast, K397N, located outside of the putative PIP2-binding site (Fig. 2a), had little effect (EC50 = 2.0 ± 0.52 μM, n = 6, p = 0.823).

Figure 2. The PIP2-binding site resides at the interface of the CaM-SK complex.

a, Molecular docking reveals that the putative PIP2-binding site includes the CaM linker and the IDF of SK2, with the following positively charged residues interacting with the PIP2 head group: R74 and K77 of CaM and K402 and K405 of the channel. K397 is located outside of the putative PIP2-binding site, ~17 Å from P5 of the PIP2 head group. b, Mutations of the four positively charged residues decrease the sensitivity of SK2 activation by diC8-PIP2 (a 3.0 – 8.0-fold increase in the EC50 for diC8-PIP2). The effects of mutations were measured in the bath solution containing 2 μM Ca2+. The numbers of experiments are shown in the parentheses of the bar graph. c, Mutations of the four positively charged residues have much less direct impact on Ca2+-dependent activation of the SK2 channels (n = 5 – 8, a 1.4 – 2.0-fold increase in the EC50 for Ca2+). At 2 μM Ca2+, the channel open probability is > 0.98 for all mutants (dashed vertical line). d, There exists a clear correlation between the Ca2+ dependent channel activation of SK channels and the apparent PIP2 affinity for the CaM-SK2 complex. Data in panels b, c and d represent mean values ± s.e.m.

While the results indicated that these selective mutants might disrupt the interaction of PIP2 with the CaM-SK2 complex at the putative PIP2-binding site, mutations could inhibit SK channels via allosteric effects due to altered energetics of channel opening. To address the potential allosteric effects by mutations, we measured the Ca2+-depedent channel activation for each mutant. The EC50 for Ca2+ dependent channel activation was increased from 0.32 ± 0.03 μM (WT, n = 8) to 0.63 ± 0.04 μM (K402N, n = 5, p < 0.001), 0.62 ± 0.04 μM (K405N, n = 6, p < 0.001), 0.56 ± 0.03 μM (R74N, n = 5, p < 0.001), and 0.44 ± 0.03 μM (K77N, n = 5, p = 0.019), while the EC50 for K397N remained unchanged (0.34 ± 0.02 μM, n = 5, p = 0.626, Fig. 2c). However, at 2 μM Ca2+, the Ca2+ concentration used to measure the PIP2 effects, the channel open probability was 0.981 – 0.997 for WT as well as the mutants (dashed vertical line, Fig. 2c), demonstrating that both WT and mutants had achieved the maximal channel open probability at 2 μM Ca2+, even though mutations caused a minor shift of the Ca2+-dependent channel activation to the right (a 1.4 – 2.0-fold increase in the EC50, Fig. 2c). Thus, K402N, K405N, R74N and K77N primarily decreased the affinity of PIP2 for the CaM-SK2 complex at 2 μM Ca2+, establishing that K402N, K405N, R74N and K77N were part of the functional PIP2-binding site. Furthermore, there was a strong correlation between Ca2+ dependent channel activation and the apparent PIP2 affinity for the CaM-SK2 complex (Fig. 2d). Collectively, these results demonstrated that the putative PIP2-binding site, identified by our docking simulations, controled the PIP2 activation of SK2 channels and suggested that these interactions serve to modulate the Ca2+-dependence of channel activation. However, at the EC50 of 1.9 μM for diC8-PIP2, the affinity of the endogenous PIP2 for the SK channel complex is likely to be much higher, casting doubts of whether decreases in PIP2 levels by hydrolysis could produce any meaningful modulation of SK channels under physiological conditions1,4,9. In the next series of experiments, we attempted to address whether the affinity of PIP2 for the SK channel complex might be subjected to modulation by cellular signaling.

Phosphorylation boosts inhibition of SK2 by PIP2 removal

Our structural model showed that a unique phosphorylation site, T79 of CaM, known to be phosphorylated by CK2 to inhibit SK channels, was located close to the PIP2-binding site (Fig. 2a). Studies have shown that the phosphorylation status at CaM T79 is determined by the combined activities of CK2 and PP2A determine16,31–33. Accordingly, two channel mutants were created, SK2(K121A), known to prevent activation of CK2, and SK2(AQAA), known to disrupt the interaction between the SK channel and PP2A, thus stopping dephosphorylation by PP2A at T7931. We used these two mutants to ask whether phosphorylation of the CaM-SK complex by CK2 might affect modulation of SK channels by PIP2. Membrane patches of SK(K121A) were exposed to 10 μM TBB, which compromises activation of the endogenous CK2, to render the CaM-SK2 complex in a dephosphorylated state at T79 (dephospho-, Fig. 3), while membrane patches of SK(AQAA) were exposed to the active catalytic domain of CK2 (CK2α) to create a permanently phosphorylated CaM-SK2 complex at T79 (phospho-, Fig. 3). Both mutants then underwent PIP2 depletion by poly-K, followed by application of diC8-PIP2.

Figure 3. Phosphorylation of CaM T79 by CK2 enhances inhibition of SK channels by PIP2.

a, After phosphorylation by the active catalytic domain of CK2 (CK2α), SK2 (AQAA) channels (phospho-) become less responsive to diC8-PIP2, resulting in a shift of the dose-response curve for diC8-PIP2 to the right (n = 6), compared with the SK2 (K121A) channels (dephospho-, n = 5). b, Phosphorylation by CK2α increases the off-rate for dissociation of the endogenous PIP2 from the CaM-SK2 complex. The apparent off-rate was measured from the time course of exposure of SK2 channels to application of poly-K. The numbers of experiments are shown in the parentheses of the bar graph. c and d, In vitro phosphorylation assays, detected by Pro-Q (c) or western blotting (WB) using an antibody against CK2 specific substrate (CK2S-Ab, d), show phosphorylation of CaM by CK2α in different conditions, as indicated. While 200 μM diC8-PIP2 produces moderate inhibition of phosphorylation by CK2α, the presence of Ca2+ virtually inhibits the CK2 activity. Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) staining showed that the same amount of CaM and the SK2 fragment (SK2 Fx) were present in all lanes (panel c). Likewise, CaM Ab blotting showed the same amount of CaM was present in all lanes (panel d). e and f. Quantification of the in vitro phosphorylation assays as shown in c and d. Gel images in c and d were quantified by normalizing the fluorescence intensity to that obtained at 0 Ca2+ without diC8-PIP2. Data in panels a, b, e, and f represent mean values ± s.e.m.

After depletion of the endogenous PIP2, application of diC8-PIP2 could restore the channel activities for both the dephosphorylated and phosphorylated CaM-SK2 complex (Supplementary Fig. 3). However, the phosphorylated channel complex required much higher diC8-PIP2 concentrations to achieve maximal activation. The EC50 for channel activation by diC8-PIP2 was increased from 1.24 ± 0.30 μM for the dephosphorylated CaM-SK2 (n = 5) to 18.04 ± 0.91 μM for the phosphorylated CaM-SK2 (n = 6), a 14.5-fold increase (p < 0.001, Fig. 3a). Furthermore, phosphorylation by CK2 significantly increased the off-rate for dissociation of the endogenous PIP2 from the CaM-SK2 complex, from 0.11 ± 0.02 s−1 for the dephosphorylated (n = 5) to 0.27 ± 0.03 s−1 for the phosphorylated (n = 7, p = 0.002, Fig. 3b). Such an increase in the off-rate greatly facilitated the inhibition of the phosphorylated SK channels by sequestration of endogenous PIP2 (Supplementary Fig. 4). In vitro phosphorylation assays were performed to confirm that use of CK2α had resulted phosphorylation of the CaM at T79, using purified CaM and the SK2 fragment. The phosphorylated CaM was readily detectable by both Pro-Q (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 5a) and an antibody against the phosphorylated CK2 substrates (CK2S-Ab, Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 5b). We further tested whether phosphorylation of the CaM-SK2 fragment by CK2α could be affected by Ca2+ or PIP2 which activate SK channels. Without Ca2+, the presence of 200 μM diC8-PIP2 produced a moderate inhibition of phosphorylation by CK2α (down to 59.0 ± 3.32% of the control, n = 6, by Pro-Q, Fig. 3e; or 77.1 ± 3.30% of the control, n = 6, by CK2S-Ab, Fig. 3f). Ca2+, on the other hand, dramatically reduced phosphorylation at T79, down to 11.7 ± 1.66% of the control (n = 6, by Pro-Q) or 18.7 ± 3.47% of the control (n = 6, by CK2S-Ab). In the presence of Ca2+, 200 μM diC8-PIP2 did not cause any further reduction of phosphorylation at CaM T79. The effects by Ca2+ are consistent with previous reports31.

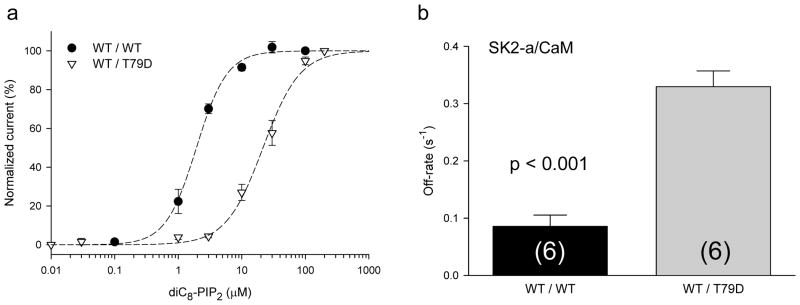

Previous studies have shown that inhibition of SK channels by CK2 can be mimicked by the phosphomimetic CaM mutant, T79D, and blocked by the CaM mutant, T79A, in mammalian cells including neurons16,31,32. The effects of CK2 phosphorylation on modulation of SK channels by PIP2 (Fig. 3) led us to test whether the phosphomimetic CaM mutant T79D could achieve the same effect on modulation of SK channels by PIP2. Coexpressed with CaM(T79D), SK2 became less responsive to diC8-PIP2 for its activation (Supplementary Fig. 6). The dose-response curve for activation of SK2 by diC8-PIP2 was significantly shifted to the right, with an 11.6-fold increase in the EC50 for diC8-PIP2, from 1.9 ± 0.22 μM (n = 6) to 22.1 ± 2.22 μM (n = 4, p < 0.001, Fig. 4a) at 2 μM Ca2+. Consistent with this observation, the apparent off-rate for dissociation of the native PIP2 from the CaM-SK2 complex was significantly increased, from 0.086 ± 0.020 s−1 (n = 6) to 0.33 ± 0.028 s−1 (n = 6, p < 0.001, Fig. 4b). The EC50 for Ca2+-dependent activation was increased as well, from 0.32 ± 0.03 μM (WT, n = 8) to 1.2 ± 0.19 μM (T79D, n = 4, 3.8-fold, p < 0.001)30, with a channel open probability of 0.88 at 2 μM Ca2+. In addition to confirming the effects of CK2 phosphorylation on modulation of SK channels by PIP2, the CaM T79D mutant would be used as an effective tool to mimic phosphorylation for later experiments.

Figure 4. The phosphomimetic CaM mutant T79D mimics the effect of phosphorylation by CK2.

a, The T79D mutant, which mimicks CK2 phosphorylation of the CaM-SK2 complex, increases the EC50 for dose-dependent activation of SK2 by diC8-PIP2 (n = 6 for WT, and n = 4 for T79D). b, T79D significantly accelerates the dissociation of PIP2 from the CaM-SK2 complex. The off-rate, obtained from fitting the time course of depletion of the endogenous PIP2 by poly-K to an exponential function, is significantly increased. The numbers of experiments are shown in the parentheses of the bar graph. Data represent mean values ± s.e.m.

Phosphorylation reduces the PIP2 affinity for CaM-SK2

In the next set of experiments, we attempted to address how phosphorylation at CaM T79, located in the vicinity of the PIP2-binding site (Fig. 2a), could facilitate modulation of SK channels by PIP2. First, we examined whether phosphorylation of CaM T79 might have changed the global conformation of the complex of CaM(T79D)-SK2 fragment by X-ray crystallography. CaM(T79D) was co-crystallized with the SK2 channel fragment in the presence of Ca2+ (Supplementary Table 1). Structure determination showed no significant changes in the global structure of the CaM(T79D)-SK2 fragment complex (blue, Fig. 5a) compared to that of the WT complex (salmon), with rmsd of 0.37 Å and 0.30 Å for CaM and the SK2 fragment, respectively. Since the crystallographic structure represents the energetically most stable conformation, we next performed molecular dynamic (MD) simulations, using the PIP2-docked structural model (Fig. 2a), to further explore any potential changes in the dynamic interactions among amino acid residues locally.

Figure 5. Phosphorylation of T79 of CaM disrupts the interaction between PIP2 and its binding site and reduces the apparent affinity of PIP2 for the CaM-SK2 complex.

a, T79D mutation does not alter the global conformation of the CaM-SK channel fragment protein complex. The crystal structure of CaM(T79D)-SK channel fragment complex (blue) was determined in the presence of Ca2+, and compared to that of the WT (salmon). b, In MD simulations, CaM(T79D) increases the distance between K77 of the PIP2-binding site and P5 of the PIP2 head group. The distance distribution histogram shows that T79D significantly increases the mean K77 – P5 distance, from 3.6 Å (WT) to 5.8 and 8.6 Å (T79D). c, T79D increases the distance between K402 of the PIP2-binding site and the P4 of the PIP2 head group. The distance distribution histogram shows that T79D significantly increases the mean K402 – P4 distance, from 3.5 Å (WT) to 8.0 Å (T79D). d and e, Snapshots from the MD simulations showing the interactions of the PIP2 phosphates to K77 of CaM, and K402 and K405 of SK2 (WT, d) and the effect of CaM(T79D) on these interactions (e).

The distance distribution histogram of the MD simulations showed that the T79D mutation reduced the mean K77 – T79 (or D79) distances from 8.5 and 11.5 Å to 2.8 and 8.0 Å, suggesting formation of a new intramolecular salt bridge between D79 and K77, a key residue of the PIP2-binding site (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 7). Further analysis showed that the T79D mutation changed how the PIP2 head group interacted with the PIP2-binding site. For instance, there was an increase in the distance between K77 and P5 of the PIP2 head group, with the mean P5 – K77 distance increased from 3.6 Å (WT) to 5.8 Å and 8.6 Å (T79D, Fig. 5b). Similarly, the distance between K402 and P4 of the PIP2 head group was also increased significantly, from 3.5 Å (WT) to 8.0 Å (T79D, Fig. 5c). Such changes were demonstrated by individual frames of MD simulations which showed that the distances for P5 – K77 and P4 – K402 were increased from 3.8 Å and 3.8 Å (WT, Fig. 5d) to 9.6 Å and 8.3 Å (T79D, Fig. 5e) respectively. Furthermore, the T79D mutation reduced the calculated interaction energy between PIP2 and its binding site in the CaM-SK2 complex from -19.20 kcal/mol (WT) to -14.99 kcal/mol (T79D), consistent with the experimental data (Figs. 3a, 3b, 4a and 4b). Thus, the MD simulation results suggested that phosphorylation of CaM T79 by CK2 could effectively weaken the interaction between PIP2 and the CaM-SK2 complex, a plausible mechanism to explain the experimental data (Figs. 3a, 3b, 4a and 4b).

Phosphorylation enhances Gq-mediated inhibition of SK2

The high apparent affinity of the SK2 channel-CaM complex for PIP2 suggests that it might serve to protect against inhibition from signals that decrease PIP2, such as PIP2 hydrolysis. If this were true, we wondered whether phosphorylation of T79 of CaM would facilitate modulation of SK2 channels by PIP2 hydrolysis stimulated by Gq protein-coupled receptors. We reconstituted the classical phospholipase C (PLC) mediated PIP2 hydrolysis using a cell line stably expressing the human muscarinic receptor (hM1R)39. Cell-attached patches were used, and the intracellular Ca2+ was elevated by application of a Ca2+ ionophore, A23187 (15 μM) in the presence of 5 μM Ca2+ in the bath solution. To eliminate potential phosphorylation of the WT CaM by endogenous CK231, we coexpressed SK2 with CaM(T79C) as the control. We have previously shown that CaM(T79C) does not have any effect on Ca2+ dependent activation of SK2 channels30. Application of acetylcholine (ACh, 10 μM) led to a moderate inhibition of the SK2 current (Fig. 6a, filled circles, and Supplementary Fig. 8a). In contrast, coexpression of CaM(T79D) greatly increased the effectiveness of ACh in its inhibition of the SK2 current under identical conditions used with CaM(T79C) (Fig. 6a, open circles, and Supplementary Fig. 8b). Likewise, coexpression of T79D increased significantly the off-rate for dissociation of the native PIP2 from the CaM-SK2 complex, from 0.019 ± 0.0019 s−1 (n = 5, T79C) to 0.029 ± 0.0038 s−1 (n = 4, T79D, p = 0.002, Fig. 6b). Consequently, the remaining current, after application of ACh, is significantly reduced, from 70.3 ± 5.2% (T79C, n = 5), compared to the current prior to ACh application, to 25.1 ± 2.84% (T79D, n = 4, p < 0.001, Fig. 6c). It is interesting to note that NS309, a positive SK channel modulator40, was able to overcome the inhibitory effect by PIP2 hydrolysis (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6. CaM T79 phosphorylation facilitates modulation of SK2 by PIP2 hydrolysis triggered by stimulation of a G-protein coupled receptor, hMR1.

a, Activation of hMR1 inhibits the SK2 channel and such inhibition is significantly enhanced by the phosphomimetic mutation, T79D. Activation of hMR1 by ACh triggers Gq-PLC-mediated hydrolysis of PIP2. T79C was used instead of WT to eliminate potential phosphorylation of WT CaM at T79. NS309, a positive SK channel modulator, or a 0 Ca2+ solution (no activity) were used to ensure that the currents recorded were indeed due to activation of SK channels by Ca2+. b, T79D significantly increases the off-rate, obtained from fitting the time course of reduction of the current amplitudes after application of ACh. c, T79D promotes inhibition of the SK2 channel activity by ACh-induced PIP2-hydrolysis. The remaining current due to ACh-induced inhibition is reduced from 70.3 ± 5.2% (n = 5, T79C) to 25.1 ± 2.84% (n = 4, T79D, p < 0.001). d, T79D facilitates inhibition of SK2 by Ci-VSP-triggered dephosphorylation of PIP2. Activation of Ci-VSP by membrane depolarization (pre-pulse) dephosphorylates PIP2 and inhibits the SK2 channel activity. This inhibitory effect is significantly increased by the T79D mutation, and the remaining current after membrane depolarization is reduced from 88.7 ± 1.6% (n = 4, no VSP) to 68.6 ± 4.7% (n = 10, T79C + VSP) and 23.1 ± 5.0% (n = 5, T79D + VSP). Data in panels b, c and d represent mean values ± s.e.m. and the numbers of experiments are shown in the parentheses of the bar graph.

ACh-induced PIP2 hydrolysis is known to activate the intracellular signaling cascades, such as generation of DAG which activates protein kinase C (PKC)1. To exclude the potential involvement of the PIP2 metabolites in inhibition of SK2 channels in our reconstituted system, we turned to the voltage-sensitive phosphatase (Ci-VSP), which dephosphorylates PI(4,5)P2 to PI(4)P39,41,42. Ci-VSP was coexpressed with CaM and SK2-a, and its activity was elicited by membrane depolarization. Activation of Ci-VSP reduced the remaining current of the T79D containing complex significantly more than the T79C containing complex (from 68.6 ± 4.67%, T79C, n = 10 to 23.1 ± 5.02%, n = 5, p < 0.001, Fig. 6d). The results suggested that the phosphomimetic T79D mutation directly facilitated the inhibition of the SK channel activity by PLC-induced PIP2 depletion. The results also lent further support of our conclusion that PIP2 was required for Ca2+-dependent activation of SK channels.

DISCUSSION

Like many other ion channels1,3, PIP2 is a necessary cofactor for the normal functions of SK channels, such as Ca2+-dependent activation of SK. Removal of PIP2, e.g. by Gq-mediated PIP2 hydrolysis, has led to inhibition of the channel activities (Figs. 1 and 6). Such inhibition is not caused by PI metabolites (Figs. 1 and 6d). Unique to this case is that the PIP2-binding site is located at the interface of the CaM-SK2 complex (Fig. 2a), including R74 and K77 of the CaM linker region and K402 and K405 within the IDF of the SK channel C-terminus. Sequence comparison shows that the amino acid residues that contribute to the PIP2-binding site are highly conserved among all SK channel family members30. IDF, a channel fragment before the CaMBD, is known to couple Ca2+ binding to CaM and channel opening30. Thus, like many other ion channels, the location of the PIP2-binding site in the CaM-SK complex is close to the channel gating machinery1,38.

Our results further show that inhibition of SK channels by PIP2 hydrolysis can be enhanced via phosphorylation of CaM T79 by CK2. CaM T79 is located at the vicinity of the PIP2-binding site (Fig. 2a). Its phosphorylation by CK2, mimicked by the phosphomimetic mutant T79D, can significantly reduce the affinity of PIP2 for its binding site and therefore enhance inhibitory effects via PIP2 hydrolysis (Figs. 3 and 4). While phosphorylation of T79 by CK2 does not produce significant global conformational changes (Fig. 5a), it significantly alters the dynamic interactions among amino acid residues surrounding the PIP2-binding site, such as formation of a new salt bridge, and ultimately weakens the interaction between the PIP2 head group and its binding site (Fig. 5). Proteins are known to exhibit dynamic behaviors, such as small-scale movements at the level of individual amino acid residues and larger-scale movements between domains at different time scales43. Changes in the dynamic interactions among amino acid residues and formation of new salt bridges are the molecular mechanisms for activation of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) upon binding of their ligands44–46.

CK2 and PP2A are known to form a signaling complex with SK channels and regulate the channel activity through phosphorylation and/or dephosphorylation31. Before this study it was unknown how phosphorylation of CaM at T79 inhibited SK channels16,31,32, although our recent work demonstrated that the phosphomimetic T79D mutation did not affect the Ca2+ sensitivity for formation of the CaM-CaMBD complex29. Based on the results of this study, we propose that the primary consequence of phosphorylation of CaM T79 by CK2 is to reduce the affinity of PIP2 for the CaM-SK channel complex and promote the inhibitory effects by PIP2 hydrolysis (Fig. 6). SK channels are known to be inhibited by activation of Gq-coupled GPCPs, such as cholinergic and adrenergic receptors15–17,33. Inhibition of SK channels in neurons by such a mechanism contributes to regulation of synaptic plasticity and memory formation15–18,47,48,49 . The results of our study provide a prime example of how physiological stimuli, such as protein phosphorylation, can directly modulate the affinity of PIP2 for its target proteins, such as ion channels, and make them more susceptible to modulation by stimuli that deplete PIP2.

METHODS

Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of this paper.

Supplementary information is available in the online version of the paper.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. John Adelman, Spike Horn, Irwin Levitan, and Steven Siegelbaum for their helpful discussions and comments on this work. We thank Dr. Masumi Eto for advice on the in vitro phosphorylation assay. We thank Dr. James P. Bennett Jr. and Ms. Laura O’Brien for sharing their mammalian cell patch clamp setup. We are grateful to Heikki Vaananen for technical assistance. We thank Dr. I. Scott Ramsey for the HEK-293 stably transfected cell line with the muscarinic M1 receptor, the structural facility of the Kimmel Cancer Center of Thomas Jefferson University for access of equipment in initial protein crystal screening and initial in-house X-ray diffraction; staff at the Beamline facility (X6A) of the Brookhaven National labs for assistance with collection of X-ray diffraction data. Use of the National Synchrotron Light Source, Brookhaven National Laboratory, was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-98CH10886. The coordinates of the CaM(T79D)-SK2 fragment complex have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with the accession code 4QNH. This work was partly supported by grants 13SDG16150007 from AHA to M.Z., S10RR027411 from NIH to M.C., HL059949 and HL090882 from NIH to D. E. L., R01MH073060 and R01NS39355 from NIH to J.F.Z.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

M.Z., D.E.L., and J.F.Z. designed the experiments. M.Z. performed electrophysiology and biochemistry experiments. carried them out. X-Y.M. and M.C. performed the docking and MD simulations. M.Z., J.F.Z., and J.M.P. performed experiments of X-ray crystallography. M.Z. and J.F.Z. analyzed the data, made figures and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All the authors participated in revising the first draft into its final form.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Supplementary information is available in the online version of the paper. Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://www.nature.com/reprints/index.html. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to D.E.L. and J.F.Z.

References

- 1.Suh BC, Hille B. PIP2 is a necessary cofactor for ion channel function: How and Why? Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:175–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delmas P, Brown DA. Pathways modulating neural KCNQ/M (Kv7) potassium channels. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:850–862. doi: 10.1038/nrn1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Logothetis D, Petrou V, Adney S, Mahajan R. Channelopathies linked to plasma membrane phosphoinositides. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol. 2010;460:321–341. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0828-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tucker SJ, Baukrowitz T. How highly charged anionic lipids bind and regulate ion channels. J Gen Physiol. 2008;131:431–438. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michailidis IE, et al. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate regulates epidermal growth factor receptor activation. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol. 2011;461:387–397. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0904-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernandez CC, Zaika O, Tolstykh GP, Shapiro MS. Regulation of neural KCNQ channels: signalling pathways, structural motifs and functional implications. J Physiol. 2008;586:1811–1821. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.148304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts-Crowley ML, Mitra-Ganguli T, Liu L, Rittenhouse AR. Regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels by lipids. Cell Calcium. 2009;45:589–601. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenhouse-Dantsker A, Logothetis D. Molecular characteristics of phosphoinositide binding. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol. 2007;455:45–53. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0291-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kruse M, Hammond GR, Hille B. Regulation of voltage-gated potassium channels by PI(4,5)P2. J Gen Physiol. 2012;140:189–205. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201210806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohler M, et al. Small-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channels from mammalian brain. Science. 1996;273:1709–1714. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5282.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faber ESL, Sah P. Functions of SK channels in central neurons. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34:1077–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stocker M. Ca2+-activated K+ channels: molecular determinants and function of the SK family. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:758–770. doi: 10.1038/nrn1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Y, et al. Molecular identification and functional roles of a Ca2+-activated K+ channel in human and mouse hearts. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49085–49094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307508200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adelman JP, Maylie J, Sah P. Small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels: Form and function. Annu Rev Physiol. 2012;74:245–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giessel AJ, Sabatini BL. M1 muscarinic receptors boost synaptic potentials and calcium influx in dendritic spines by inhibiting postsynaptic SK channels. Neuron. 2010;68:936–947. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maingret F, et al. Neurotransmitter modulation of small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels by regulation of Ca2+ gating. Neuron. 2008;59:439–449. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchanan KA, Petrovic MM, Chamberlain SEL, Marrion NV, Mellor JR. Facilitation of long-term potentiation by muscarinic M1 receptors is mediated by inhibition of SK channels. Neuron. 2010;68:948–963. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faber ESL. Functional interplay between NMDA receptors, SK channels and voltage-gated Ca2+ channels regulates synaptic excitability in the medial prefrontal cortex. J Physiol. 2010;588:1281–1292. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.185645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mpari B, Sreng L, Manrique C, Mourre C. KCa2 channels transiently downregulated during spatial learning and memory in rats. Hippocampus. 2010;20:352–363. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kramár EA, et al. A novel mechanism for the facilitation of theta-induced long-term potentiation by brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5151–5161. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0800-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stackman RW, et al. Small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels modulate synaptic plasticity and memory encoding. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10163–10171. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10163.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKay BM, Oh MM, Disterhoft JF. Learning increases intrinsic excitability of hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci. 2013;33:5499–5506. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4068-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garland CJ. Compromised vascular endothelial cell SKCa activity: a fundamental aspect of hypertension? Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:833–835. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00692.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Köhler R. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in vascular Ca2+ activated K+-channel genes and cardiovascular disease. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol. 2010;460:343–351. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0768-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.SK2 channels are neuroprotective for ischemia-induced neuronal cell death. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:2302–2312. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chou CC, Lunn CA, Murgolo NJ. KCa3.1: target and marker for cancer, autoimmune disorder and vascular inflammation? Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2008;8:179–187. doi: 10.1586/14737159.8.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kasumu AW, et al. Selective positive modulator of calcium-activated potassium channels exerts beneficial effects in a mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 2. Chem Biol. 2012;19:1340–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang M, et al. Structural basis for calmodulin as a dynamic calcium sensor. Structure. 2012;20:911–923. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xia XM, et al. Mechanism of calcium gating in small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Nature. 1998;395:503–507. doi: 10.1038/26758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang M, Pascal JM, Zhang JF. Unstructured to structured transition of an intrinsically disordered protein peptide in coupling Ca2+-sensing and SK channel activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:4828–4833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220253110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allen D, Fakler B, Maylie J, Adelman JP. Organization and regulation of small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel multiprotein complexes. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2369–2376. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3565-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bildl W, et al. Protein kinase CK2 Is coassembled with small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels and regulates channel gating. Neuron. 2004;43:847–858. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagner EJ, Rønnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. The noradrenergic inhibition of an apamin-sensitive, small-conductance Ca2+ -activated K+ channel in hypothalamic γ-aminobutyric acid neurons: Pharmacology, estrogen sensitivity, and relevance to the control of the reproductive axis. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 2001;299:21–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang M, Pascal JM, Schumann M, Armen RS, Zhang JF. Identification of the functional binding pocket for compounds targeting small-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channels. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1021. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang H, et al. PIP(2) activates KCNQ channels, and its hydrolysis underlies receptor-mediated inhibition of M currents. Neuron. 2003;37:963–975. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rohács T, et al. Specificity of activation by phosphoinositides determines lipid regulation of Kir channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:745–750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0236364100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenhouse-Dantsker A, et al. A sodium-mediated structural switch that controls the sensitivity of Kir channels to PtdIns(4,5)P2. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:624–631. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hansen SB, Tao X, MacKinnon R. Structural basis of PIP2 activation of the classical inward rectifier K+ channel Kir2.2. Nature. 2011;477:495–498. doi: 10.1038/nature10370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murata Y, Iwasaki H, Sasaki M, Inaba K, Okamura Y. Phosphoinositide phosphatase activity coupled to an intrinsic voltage sensor. Nature. 2005;435:1239–1243. doi: 10.1038/nature03650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pedarzani P, et al. Specific Enhancement of SK Channel Activity Selectively Potentiates the Afterhyperpolarizing Current IAHP and Modulates the Firing Properties of Hippocampal Pyramidal Neurons. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41404–41411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509610200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horn R. Electrifying Phosphatases. Sci STKE. 2005;2005:pe50. doi: 10.1126/stke.3072005pe50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iwasaki H, et al. A voltage-sensing phosphatase, Ci-VSP, which shares sequence identity with PTEN, dephosphorylates phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7970–7975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803936105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Henzler-Wildman K, Kern D. Dynamic personalities of proteins. Nature. 2007;450:964–972. doi: 10.1038/nature06522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kobilka BK. Structural insights into adrenergic receptor function and pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011;32:213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenbaum DM, Rasmussen SGF, Kobilka BK. The structure and function of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 2009;459:356–363. doi: 10.1038/nature08144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nygaard R, et al. The Dynamic Process of β2-Adrenergic Receptor Activation. Cell. 2013;152:532–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martina M, Turcotte MEB, Halman S, Bergeron R. The sigma-1 receptor modulates NMDA receptor synaptic transmission and plasticity via SK channels in rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2007;578:143–157. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.116178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hammond RS, et al. Small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel type 2 (SK2) modulates hippocampal learning, memory, and synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1844– 1853. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4106-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blank T, Nijholt I, Kye MJ, Radulovic J, Spiess J. Small-conductance, Ca2+-activated K+ channel SK3 generates age-related memory and LTP deficits. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:911–912. doi: 10.1038/nn1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Collaborative Computational Project N. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallographica Section D. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peralta EG, Ashkenazi A, Winslow JW, Ramachandran J, Capon DJ. Differential regulation of PI hydrolysis and adenylyl cyclase by muscarinic receptor subtypes. Nature. 1988;334:434–437. doi: 10.1038/334434a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morris GM, et al. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J Comput Chem. 1998;19:1639–1662. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Breneman CM, Wiberg KB. Determining atom-centered monopoles from molecular electrostatic potentials-The need for high sampling density in formamide conformational analysis. J Comp Chem. 1990;11:361–373. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frisch MJ, et al. Gaussian 98. Gaussian, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meng XY, Zhang HX, Logothetis Diomedes E, Cui M. The Molecular Mechanism by which PIP2 Opens the Intracellular G-Loop Gate of a Kir3.1 Channel. Biophysi J. 2012;102:2049–2059. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.03.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bowers KJ, et al. Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE Conference on Supercomputing (SC06); 2006. pp. 11–17. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.