Abstract

Melioidosis is a tropical bacterial infection caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei (B. pseudomallei; Bpm), a Gram-negative bacterium. Current therapeutic options are largely limited to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and β-lactam drugs, and the treatment duration is about 4 months. Moreover, resistance has been reported to these drugs. Hence, there is a pressing need to develop new antibiotics for Melioidosis. Inhibition of enoyl-ACP reducatase (FabI), a key enzyme in the fatty acid biosynthesis pathway has shown significant promise for antibacterial drug development. FabI has been identified as the major enoyl-ACP reductase present in B. pseudomallei. In this study, we evaluated AFN-1252, a Staphylococcus aureus FabI inhibitor currently in clinical development, for its potential to bind to BpmFabI enzyme and inhibit B. pseudomallei bacterial growth. AFN-1252 stabilized BpmFabI and inhibited the enzyme activity with an IC50 of 9.6 nM. It showed good antibacterial activity against B. pseudomallei R15 strain, isolated from a melioidosis patient (MIC of 2.35 mg/L). X-ray structure of BpmFabI with AFN-1252 was determined at a resolution of 2.3 Å. Complex of BpmFabI with AFN-1252 formed a symmetrical tetrameric structure with one molecule of AFN-1252 bound to each monomeric subunit. The kinetic and thermal melting studies supported the finding that AFN-1252 can bind to BpmFabI independent of cofactor. The structural and mechanistic insights from these studies might help the rational design and development of new FabI inhibitors.

Keywords: Melioidosis, Burkholderia pseudomallei, FabI, AFN-1252

Introduction

Melioidosis is an infectious disease caused by the Gram-negative organism Burkholderia pseudomallei that affects both humans and animals.1–3 This infection is recognized as an important health problem in southeast Asia and tropical northern Australia.4 Clinical manifestations of naturally occurring melioidosis include pneumonia with or without septicemia or localized infections involving skin and soft tissue organs.5 Chronic disease might also occur; symptoms of which mimic those of tuberculosis, and it is clinically challenging to distinguish these two diseases. Current treatment options include ceftazidime or carbapenem as IV dosing for two weeks during the initial intensive phase of therapy followed by twelve weeks of oral therapy.6,7 Drug resistance has already been reported with current treatment, suggesting that developing an effective treatment for B. pseudomallei infection will be a challenging task.8,9 Moreover, B. pseudomallei is intrinsically resistant to several classes of antibiotics due to expression of resistance determinants such as beta-lactamase and multidrug efflux pumps.10 Hence, there is an urgent need for developing new drugs that function through novel mechanisms of action.

Type II bacterial fatty acid synthesis (FASII) is an essential pathway for both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and offers an attractive target for antibacterial drug development.11,12 However, some bacteria can bypass the FASII inhibition by utilizing external fatty acids.13,14 In FASII system, bacteria utilizes specific enzymes at different stages of the biosynthesis pathway as compared to the multienzyme complex mediated synthesis of fatty acids in FASI.15 The final step in each cycle of Type II bacterial fatty acid synthesis is the 1,4-reduction of an enoyl-ACP to the corresponding acyl-ACP catalyzed by an enoyl-ACP reductase utilizing NAD(P)H as cofactor. Four different isoforms of enoyl-ACP reductase have been discovered, namely FabI, FabK, FabL, and FabV.16 Bacteria uses one or more isoforms for fatty acid biosynthesis. Among these four subtypes, FabI has become an attractive target for antibacterial drug discovery and many compounds have already been identified as inhibitors of this enzyme (from different bacterial species).17,18 FabI, the only isoform present in Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus; Sa) has been the target of intense drug discovery efforts for staphylococcal infections.19,20 Among other isoforms, FabV has also emerged as a potential target.21 B. pseudomallei has three enoyl-ACP reductases- FabI1, FabI2, and FabV. Using knockout and inhibition studies, Cummings et al. showed that FabI1 (referred as FabI in this article) is the major enoyl-ACP reductase present in B. pseudomallei.17

AFN-1252, developed by Affinium Pharmaceuticals is the most advanced FabI inhibitor in clinical development.22–24 Chemical structure of AFN-1252 is given in Figure 1(a). The pro-drug AFN-1720 has now been developed for the IV dosing of this compound. After the acquisition of these molecules from Affinium Pharmaceuticals by DebioPharm, these compounds were named as Debio 1452 and Debio 1450, respectively.25 In 2013, Affinium completed the oral Phase 2 clinical study of AFN-1252 in acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections caused by Staphylococci and successfully demonstrated efficacy and safety in humans. AFN-1252 is reported to have an IC50 of 14 nM for SaFabI and MIC50 in the range 0.002–0.12 mg/L for S. aureus bacterial growth.26 AFN-1252 is potent against drug resistant Staphylococci including methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aereus (MRSA) and methicillin resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE).27,28 AFN-1252 is also known to inhibit FabI from Chlamydia trachomatis (CtFabI) and E. coli.29 Triclosan [Fig. 1(b)] is another well characterized inhibitor of FabI from multiple species including B. pseudomallei.30,31 It has been widely used as a broad spectrum biocide. Binding of Triclosan to FabI has been studied extensively using various biophysical and biochemical methods which lead to the design of more potent Triclosan analogs.32

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of (a) AFN-1252 and (b) Triclosan.

In this study, we evaluated the potential of AFN-1252 for its BpmFabI inhibitory activity. Furthermore, a detailed crystal structure analysis of the BpmFabI:AFN-1252 complex was carried out. The mechanistic and structural information on the binding of AFN-1252 to BpmFabI obtained from this study is expected to be useful in the design of more potent and efficacious BpmFabI inhibitors to treat melioidosis.

Results

AFN-1252 is a potent inhibitor of BpmFabI

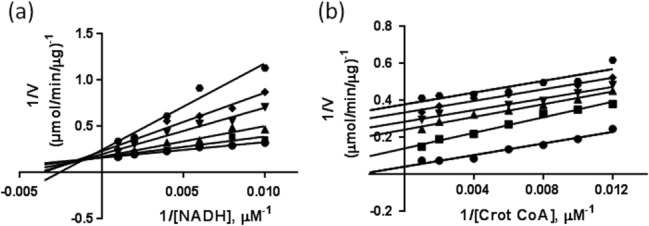

Inhibition of BpmFabI enzyme was studied by determining the activity of the enzyme at different concentrations of AFN-1252. As shown in Figure 2, AFN-1252 inhibited BpmFabI with an IC50 of 9.6 nM. To understand the mechanism of inhibition of BpmFabI by AFN-1252 in the presence of NADH and crotonyl-CoA, Lineweaver–Burk plots were generated at different concentrations of AFN-1252. In these experiments, concentration of either crotonyl-CoA or NADH was varied, keeping the other constant. Figure 3(a) shows the Lineweaver–Burk plot for AFN-1252 binding to BpmFabI at 300 µM crotonyl-CoA and varying concentrations of NADH. Increase in Km with increasing concentrations of AFN-1252, and a corresponding decrease in Vmax suggest mixed inhibition of BpmFabI in which AFN-1252 can bind to enzyme directly, and also compete with NADH bound to BpmFabI. The Lineweaver–Burk plot for AFN-1252 binding to BpmFabI at 375 μM NADH and varying concentrations of crotonyl-CoA is shown in Figure 3(b). Decrease in Km with a corresponding decrease in Vmax suggests that AFN-1252 is uncompetitive with crotonyl-CoA, and its binding to BpmFabI is independent of the substrate. The Michaelis–Menten (M–M) data was also analyzed by fitting it to M-M equation to generate Km and Vmax values. When the concentration of crotonyl-CoA was varied, both Km and Vmax decreased with increasing concentration of AFN-1252. On the other hand, an increase in Km and decrease in Vmax was observed when NADH concentration was varied (Supporting Information data). Similar binding mechanism for AFN-1252 was deduced from both Lineweaver–Burk and Michaelis–Menten equations.

Figure 2.

Dose-response curve for the inhibition of BpmFabI by AFN-1252.

Figure 3.

Mechanism of inhibition of BpmFabI by AFN-1252 (a) at 300 µM crotonyl-CoA and different concentrations of NADH and (b) at 375 µM NADH and different concentrations of crotonyl- CoA. The concentrations of AFN-1252 used were: 0 nM (•), 2.5 nM (▪), 5 nM (▴), 10 nM (▾), 20 nM (♦), and 40 nM ( ) [Fig. 3(a)]; and 0 nM (•), 5 nM (▪), 20 nM (▴), 40 nM (▾), 80 nM (♦), and 160 nM (

) [Fig. 3(a)]; and 0 nM (•), 5 nM (▪), 20 nM (▴), 40 nM (▾), 80 nM (♦), and 160 nM ( ) [Fig. 3(b)].

) [Fig. 3(b)].

Binding of AFN-1252 to BpmFabI was also monitored by thermofluor assay. An increase in melting temperature of ∼12°C with AFN-1252 indicated stabilization of the enzyme by this inhibitor (Fig. 4 and Table1). NADH did not have any effect on the Tm of BpmFabI or BpmFabI: AFN-1252 complex. For comparison, we carried out similar experiments with Triclosan. Interestingly, Triclosan stabilized BpmFabI only in the presence of NADH (ΔTm of ∼9°C); neither NADH nor Triclosan alone stabilized the protein. This data suggests the formation of a ternary complex of BpmFabI-Triclosan-NADH, as reported earlier.33

Figure 4.

Thermal melting curves of BpmFabI alone (▪) and in presence of AFN-1252 (▴) and Triclosan (○).

Table 1.

Stabilization Effect of AFN-1252/Triclosan on BpmFabI

| Ligand | ΔTm (°C) |

|---|---|

| NADH | 0 |

| AFN-1252 | 12.76 ± 1.26 |

| AFN-1252 + NADH | 11.61 ± 0.10 |

| Triclosan | 0 |

| Triclosan + NADH | 8.49 ± 0.32 |

Inhibition of B. pseudomallei bacterial growth by AFN-1252

To determine whether inhibition of BpmFabI translates in to antibacterial activity, we determined MIC of AFN-1252 against B. pseudomallei BpR15 strain. AFN-1252 inhibited the bacterial growth with MIC of 2.33 mg/L. Similar potency was observed with Triclosan (2.35 mg/L). Liu et al. studied the B. pseudomallei inhibition by Triclosan and they reported MIC90 of 30 mg/L for 90% growth inhibition of B. pseudomallei.

Monomer and quaternary structures of the BpmFabI

X-ray structure of BpmFabI-AFN-1252 complex was determined and the coordinates have been deposited in the protein data bank (accession code PDB 4RLH). The final model containing residues 1 to 258 is complete except for residues Ile192 to Ser198 which could not be modeled due to poor electron density. The structural models were generated using Pymol.34 Summary of the data reduction and structure refinement statistics is provided in Table2.

Table 2.

Diffraction Data and Structure Refinement Statistics of BpmFabI: AFN-1252 Complex

| PDB code | 4RLH |

|---|---|

| Space group | C2 |

| Cell parameters (Å) | a = 134.79, b = 63.44, c = 121.84, β = 107.08° |

| Resolution range (Å) | 40–2.26 |

| Total no. reflections | 114,107 |

| Unique reflections | 42,792 |

| Completeness (%) | 93.11 (89.9)a* |

| Rsym | 0.062 (0.157) |

| I/σI | 11.8 (2.6) |

| Multiplicity | 2.7(2.7) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 40–2.26 |

| No. of reflections | 40,619 |

| Completeness (%) | 92.48 (79.28) |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.161/0.250 |

| r.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.015 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.855 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Residues in the most favored region (%) | 96.5 |

| Residues in the allowed region (%) | 3.5 |

a*—Values corresponding to the outermost shell are given within parentheses.

The overall structure of BpmFabI in complex with AFN-1252 is similar to the earlier reported apo-structure of Bpm FabI (PDB:3EK2) and ternary complex structures of Ec (E. coli: PDB:4JQC), and SaFabI (PDB:4FS3) with AFN-1252 and NAD/NADPH.19,35 Multiple attempts to crystallize the ternary complex of BpmFabI with NAD/NADH and AFN-1252 were not successful. The BpmFabI monomer contains a single domain composed of a seven-stranded parallel β-sheet (β1, β2, β3, β4, β5 β6, β7) sandwiched by three α-helices from the top (α1, α2, α3) and three from the bottom (α4, α5, α6). Another helix, α7 is located at the C terminal tail of the protein (Fig. 5). The overall fold is common to dinucleotide-binding FabI enzymes and resembles the typical Rossmann fold. The structural superposition showed an r.m.s. deviation of 1.047, 0.87, and 1.07 Å, respectively, for Bpm (256 Cα atoms; 3EK2), Ec (251 Cα atoms; 4JQC), and SaFabI (242 Cα atoms; 4FS3) crystal structures.

Figure 5.

Ribbon representation of the monomeric structure of BpmFabI (cyan) with the bound ligand AFN-1252 (yellow). The monomer is composed of seven α helices and seven β strands.

The crystallographic asymmetric unit consists of four protomers arranged as a tetramer with an approximate 222 symmetry (Fig. 6). The elements involved in the tetramer formation include the β7 strand, helices α4 and α5, and the C-terminal tail which cross over to the neighboring monomer. The helices α4 and α5 from the two monomers interact with each other to create a strong dimer. The β7 strand from the seven stranded β-sheet of each dimer associates to form an extended 14 stranded β-sheet, which facilitate the formation of a stable tetrameric assembly. This larger assembly may represent the biologically active form of BpmFabI. This is further supported by analytical gel filtration experiments which indicated a tetrameric protein in solution (Data not shown).

Figure 6.

Ribbon diagram of BpmFabI tetrameric assembly viewed down the twofold noncrystallographic axis. Each monomer along with the bound AFN-1252 is shown in a different color.

Binding site structure of AFN-1252-BpmFabI binary complex

The electron density for AFN-1252 was clearly visible in the active site cavity in all four subunits. The flexible loop containing protein residues 194 to 204 accommodates the AFN-1252 molecule in the binding pocket. AFN-1252 binding to BpmFabI is mediated through multiple chemical interactions (Fig. 7). The tetrahydronaphthyridone moiety of the molecule makes two hydrogen bonds to the main chain atoms of Ala95. A water mediated interaction is observed between the main chain –NH atom of Arg97 and the –CO group of napthyridinone ring. The amide –CO group of the inhibitor also forms hydrogen bonds with the side chain of Tyr156 and a water mediated interaction with Lys163 side chain. The 3-methylbenzofuran moiety is located in a hydrophobic pocket created by the side chains of Ile100, Tyr146, Tyr156, Pro191, Phe203, and Ile206.

Figure 7.

Active site structure of AFN-1252 bound to BpmFabI. The interacting residues seen within 3.6 Å distance from AFN-1252 are labeled. Hydrogen bonds are represented as dotted lines and water molecules as red spheres.

Comparison of crystal structures of AFN-1252: BpmFabI complex with the apo-BpmFabI (PDB:3EK2) revealed no major conformational changes except in the active site region. Near the active site, the loop containing residues Thr194-Lys199 adopts ordered conformation as a result of AFN-1252 binding, whereas the same loop is highly disordered in the apo structure. Thus, the change in loop conformation appears to have been induced by the AFN-1252 binding. Further, involvement of this flexible loop in the formation of ternary complexes across FabIs is well established (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Cartoon diagram showing the superposed structures of Bpm (magenta), Sa (yellow), and EcFabI (green). The bound NAD/NADP and AFN-1252 ligands are also shown. The flexible loop (residues T194-K199) in BpmFabI was found protruding away from the active site.

Ternary complexes of AFN-1252 and cofactor bound to EcFabI (PDB:4JQC), SaFabI (PDB:4FS3) and CtFabI (PDB:4Q9N) are reported in literature.17,32 Strong hydrogen bonds and π-π contacts were observed between the cofactor and AFN-1252. We have compared the AFN-1252:BpmFabI binary crystal structure against the reported ternary complex structure of AFN-1252:NADPH:SaFabI and AFN-1252:NADH:EcFabI.19,35 In the ternary complexes, 2-hydroxyl and 3-hydroxyl of nicotinamide ribose (of NADPH/NADH) form hydrogen bonds with side chains of Tyr157 and Lys164, respectively. Pyridyl nitrogen and N-acyl hydrogen of the tetrahydronaphthyridone moiety in AFN-1252 make hydrogen bonds with the carbonyl moiety of peptide backbone and amide group of Ala95. The 3-methylbenzofuran group forms an edge-to-face-interaction with the side chain of Phe204. In BpmFabI:AFN1252 complex, we observed water molecules corresponding to 2-hydroxyl and 3-hydroxyl group positions of ribose ring in Ec and SaFabI:AFN1252 ternary complexes. These water molecules mediate interactions between AFN-1252 and the BpmFabI, similar to that mediated by the cofactor in Ec and SaFabI ternary structures. The amino acid side chain of, Lys163, –CO group of Ile92 and side chain of His90 in BpmFabI are involved in these interactions. Therefore, the water mediated interactions between AFN-1252 and BpmFabI may compensate for the lack of cofactor mediated interactions seen in the ternary complex of AFN-1252 bound to Ec and SaFabI.

Comparison of AFN-1252 bound binary (this study) and ternary complex structures revealed no major conformational changes due to the presence of cofactor in the active site (Fig. 8). Thus the BpmFabI binary complex structure establishes that an inhibitor binding is feasible in the absence of the cofactor. This important finding suggests that inhibitors for BpmFabI can be designed by considering interactions solely with protein residues.

Discussion

Identification of new targets with novel mechanism of action has become imperative for the development of antibiotics with improved potency and to address bacterial resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. As compared to Gram-positive bacteria, development of antibiotics against Gram-negative bacteria has an added challenge due to the presence of an additional membrane in the cell wall that act as a filter for the transport of therapeutic compounds.36 Ability of different antibiotics to traverse through the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria is defined by its lipid and protein composition and also on efflux pump mechanisms in drug transport.

Fatty acid biosynthetic pathway is being actively pursued for the development of antibacterial agents. As FabI catalyzes the last step in fatty acid chain elongation and play a determinant role, it was identified as a specific cellular target for therapeutic intervention. As AFN-1252, the FabI inhibitor, is reported to be selective for Gram-positive S. aureus, it was interesting to see that it was active against Gram-negative B. pseudomallei bacterium. FabI enzymes from Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria have significant sequence and structural similarity. Hence, an understanding of the mechanism of binding of the inhibitors to FabI and the structural insights from FabI-inhibitor complexes will be useful in designing new inhibitors of both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria.

The MIC for the inhibition of B. pseudomallei growth by AFN-1252 is significantly higher than that is expected from its biochemical potency for BpmFabI inhibition. Presence of efflux pump in B. pseudomallei and permeability related drug penetration issues could be major factors responsible for the lower than expected antibacterial activity of the compound. In addition to FabI enzyme, another enoyl reductase, FabV is also known to be present in B. pseudomallei.33 Although the role of this FabV enzyme is not very clear, it is possible that both homologues FabI and FabV have to be inhibited to prevent complete fatty acid synthesis.

Previously reported crystal structures show that Ec, Sa, and CtFabI Enzymes form ternary complexes with AFN-1252 and NADH/NADPH. Similarly, ternary complex is reported for BpmFabI with Triclosan and NADH. However, the data presented in this study shows that AFN-1252 can form a binary complex with BpmFabI, in the absence of the cofactor. Thermal melting studies support this independent binding of AFN-1252 to BpmFabI. Shift of ∼12°C in melting temperature shows significant stabilization of BpmFabI upon AFN-1252 binding. Mixed mode of inhibition observed in kinetic studies suggests that AFN-1252 can either directly bind to the enzyme or compete with NADH for BpmFabI binding site.

Specificity of FabI for the cofactor is important for enzyme activity.37 We tested both NADH and NADPH as cofactors, but activity was seen only with NADH, suggesting that it is a specific cofactor for BpmFabI. In the thermal melting studies, apart from NADH, we determined the stabilization effect of NADPH and NAD+ on BpmFabI. NADPH did not have any effect on BpmFabI, while NAD+ mediated ternary complex formation with Triclosan. Also, binding of AFN-1252 to BpmFabI was independent of NAD+.

In conclusion, our data shows that AFN-1252 is a potent inhibitor of BpmFabI with good antibacterial activity against B. pseudomallei. Co-crystal structure and thermofluor data demonstrated that AFN-1252 forms a stable binary complex with BpmFabI. Kinetic studies showed that AFN-1252 can compete with NADH, but the binding is uncompetitive with crotonyl-CoA. The results of the binding studies and identification of key interactions of AFN-1252 with BpmFabI might be useful in designing and developing more potent BpmFabI inhibitors to treat melioidosis.

Materials and Methods

Expression and purification of BpmFabI isoform 1

Cell pellet from E. coli BL21 (DE3) transformants containing pET21a-BpmFabI 1–263 (amino acids of Isoform 1) was washed with lysis buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl 1 mM PMSF, and 5 mM Imidazole) and treated with 50 μg/mL lysozyme for 30 min.16 The supernatant of cell lysate was bound to Ni-NTA beads pre-equilibrated with 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, and 5 mM imidazole buffer, and eluted with 500 mM imidazole. Fractions containing BpmFabI passed through Superdex-75 column in 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole.

BpmFabI enzyme inhibition assay for AFN-1252

AFN-1252 was synthesized in-house using a published synthetic scheme.38 The potency of AFN-1252 to inhibit BpmFabI was evaluated in a spectrophotometric assay by monitoring the oxidation of the cofactor NADH.33 Buffer used for the assay was 30 mM PIPES, pH 6.8, containing 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA. 175 nM BpmFabI enzyme was used in the assay. Michaelis–Menton constant (Km) and Kcat were determined from the enzyme activity at increasing concentrations of crotonyl-CoA. The values of Km (257 µM) and Kcat (307 min−1) were slightly higher than the reported values (188 µM and 215 min−1, respectively). To determine the IC50, AFN-1252 was preincubated with BpmFabI for 30 min and the reaction was started by adding substrate mix containing crotonyl-CoA (300 µM) and NADH (375 µM). The oxidation of NADH was monitored by following the decrease of absorbance at 340 nm. IC50 value was determined by fitting the dose-response data to sigmoidal dose response (variable slope) curve using Graphpad Prism software V4. To determine the mechanism of binding, kinetic studies were carried out at different concentrations of inhibitor and varying the concentration of NADH at a fixed concentration of crotonoyl-CoA (300 µM) and also by varying the concentrations of crotonoyl-CoA keeping NADH concentration fixed at 375 µM. Lineweaver–Burk plots were subsequently generated to determine the mechanism of binding of AFN-1252 to BpmFabI.

Thermofluor assay

Melting temperature of BpmFabI protein in presence and absence of inhibitors were determined with ABI Prism 7500 instrument (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad) in the presence of 5× SYPRO Orange dye. 2 µM BpmFabI in 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole with/without 50 µM NADH was incubated with 20 µM AFN-1252/Triclosan for 1 h followed by the addition of SYPRO Orange dye. Melting temperatures were determined with Boltzmann equation using Protein thermal shift™ software version 1.1.

Minimum inhibitory concentration determination assay

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determination was carried out using the microdilution technique described by Wiegand et al. with some modifications.39 A twofold serial dilution of the compound was prepared in Brain Heart infusion broth (BHIB) and dispensed into 96-well plate. An inoculum of 1 × 108 cfu/mL of BpR15 was added into each well and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Growth control (bacterial inoculum only), sterility control (broth only) and positive control (bacterial inoculum with Triclosan) wells were prepared and incubated simultaneously. The MIC, defined as the lowest concentration of AFN-1252 that inhibited visible growth of BpR15, was recorded. The MIC results are average of n = 2.

Bacterial isolate and sample preparation

Burkholderia pseudomallei strain R15 (herein referred to as BpR15) was isolated from an individual who succumbed to melioidosis at the Kuala Lumpur Hospital in Malaysia.40 BpR15 was routinely cultured on Ashdown agar at 37°C and overnight bacterial cultures were prepared in BHIB. AFN-1252 was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at −20°C until use.

Crystallization of BpmFabI isoform 1

Co-crystals of BpmFabI with AFN-1252 were obtained using hanging drop vapor diffusion technique. Concentrated protein (15 mg/mL) was incubated overnight with 0.5 mM AFN-1252 and 1 mM NADH in a reservoir buffer containing 0.1M MES pH 5.0, 0.1M NaCl, 10% PEG 3350.

X-ray data collection and structure determination

Co-crystals of BpmFabI with AFN-1252 were flash frozen at 100 K using 20% glycerol as cryoprotectant. The diffraction data was collected using in-house Rigaku RU300 X-ray generator with R-AXIS IV ++ detector (Texas) to a maximum resolution of 2.26 Å. Data indexing, integration and scaling were performed using DENZO and SCALEPACK.41 Structure was solved by molecular replacement (MR) method using the search model with PDB Code; 3EK2. Alternate cycles of restrained refinement and manual rebuilding were performed with the programs REFMAC 5.2.0001 42 and Coot,43 respectively. Five percent of the reflections were randomly excluded from the refinement to monitor the free residual-factor (Rfree).

Acknowledgments

Rohana Yusof and Noorsaadah Abd. Rahman like to acknowledge the support from the University of Malaya, Malaysia. The authors are thankful to Prakrith, V N of Aurigene Discovery Technologies Ltd for providing support during the research work. All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare relevant to this study.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Supplementary Information

References

- Hayden HS, Lim R, Brittnacher MJ, Sims EH, Ramage ER, Fong C, Wu Z, Crist E, Chang J, Zhou Y, Radey M, Rohmer L, Haugen E, Gillett W, Wuthiekanun V, Peacock SJ, Kaul R, Miller SI, Manoil C, Jacobs MA. Evolution of Burkholderia pseudomallei in Recurrent Melioidosis. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36507, 1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limmathurotsakul D, Thammasart S, Warrasuth N, Thapanagulsak P, Jatapai A, Pengreungrojanachai V, Anun S, Joraka W, Thongkamkoon P, Saiyen P, Wongratanacheewin S, Day NP, Peacock SJ. Melioidosis in animals, Thailand, 2006–2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18(2):325–327. doi: 10.3201/eid1802.111347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiersinga WJ, Currie BJ, Peacock SJ. Melioidosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(11):1035–1044. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1204699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limmathurotsakul D, Peacock SJ. Melioidosis: a clinical overview. Br Med Bull. 2011;99:125–139. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldr007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng AC, Currie BJ, Dance DA, Funnell SG, Limmathurotsakul D, Simpson AJ, Peacock SJ. Clinical definitions of melioidosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88(3):411–413. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dance D. Treatment and prophylaxis of melioidosis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014;43(4):310–318. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes DM, Dow SW, Schweizer HP, Torres AG. Present and future therapeutic strategies for melioidosis and glanders. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2010;8(3):325–338. doi: 10.1586/eri.10.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer HP. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in Burkholderia pseudomallei: implications for treatment of melioidosis. Future Microbiol. 2012;7(12):1389–1399. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarovich DS, Price EP, Limmathurotsakul D, Cook JM, Von Schulze AT, Wolken SR, Keim P, Peacock SJ, Pearson T. Development of ceftazidime resistance in an acute Burkholderia pseudomallei infection. Infect Drug Resist. 2012;5:129–132. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S35529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RA, DeShazer D, Reckseidler S, Weissman A, Woods DE. Efflux-mediated aminoglycoside and macrolide resistance in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43(3):465–470. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.3.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JW, Cronan JE., Jr Bacterial fatty acid biosynthesis: targets for antibacterial drug discovery. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:305–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JB, Rock CO. Is bacterial fatty acid synthesis a valid target for antibacterial drug discovery? Curr Opin Microbiol. 2011;14:544–549. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinster S, Lamberet G, Staels B, Trieu-Cuot P, Gruss A, Poyart C. Type II fatty acid synthesis is not a suitable antibiotic target for Gram-positive pathogens. Nature. 2009;458(7234):83–86. doi: 10.1038/nature07772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JB, Frank MW, Subramanian C, Saenkham P, Rock CO. Metabolic basis for the differential susceptibility of Gram-positive pathogens to fatty acid synthesis inhibitors Proc Natl. Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(37):15378–15383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109208108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Ma S. Recent advances in inhibitors of bacterial fatty acid synthesis type II (FASII) system enzymes as potential antibacterial agents. Chem Med Chem. 2013;8(10):1589–1608. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201300209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JE, Kingry LC, Rholl DA, Schweizer HP, Tonge PJ, Slayden RA. The Burkholderia pseudomallei enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase FabI1 is essential for in vivo growth and is the target of a novel chemotherapeutic with efficacy. Antimicrob Agents and Chemother. 2014;58(2):931–935. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00176-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Tonge PJ. Inhibitors of FabI, an enzyme drug target in the bacterial fatty acid biosynthesis pathway. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41(1):11–20. doi: 10.1021/ar700156e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath RJ, Yu Y, Shapiro MA, Olson E, Rock CO. Broad spectrum antimicrobial biocides target the FabI component of fatty acid synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30316–30320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takhi M, Sreenivas K, Reddy CK, Munikumar M, Praveena K, Sudheer P, Rao BN, Ramakanth G, Sivaranjani J, Mulik S, Reddy YR, Narasimha Rao K, Pallavi R, Lakshminarasimhan A, Panigrahi SK, Antony T, Abdullah I, Lee YK, Ramachandra M, Yusof R, Rahman NA, Subramanya H. Discovery of azetidine based ene-amides as potent bacterial enoyl-ACP reductase (FabI) inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2014;84:382–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WH, Seefeld MA, Newlander KA, Uzinskas IN, Burgess WJ, Heerding DA, Yuan CC, Head MS, Payne DJ, Rittenhouse SF, Moore TD, Pearson SC, Berry V, DeWolf WE, Jr, Keller PM, Polizzi BJ, Qiu X, Janson CA, Huffman WF. Discovery of aminopyridine-based inhibitors of bacterial enoyl-ACP reductase (FabI) J Med Chem. 2002;45:3246–3256. doi: 10.1021/jm020050+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji BT, Harigaya Y, Lesse AJ, Forrest A, Ngo D. Mechanism and inhibition of the FabV enoyl-ACP reductase from Burkholderia Malle. Biochemistry. 2010;49:1281–1289. doi: 10.1021/bi902001a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji BT, Harigaya Y, Lesse AJ, Forrest A, Ngo D. Activity of AFN-1252 -a novel FabI inhibitor, against Staphylococcus aureus in an in vitro pharmacodynamic model simulating human pharmacokinetics. J Chemother. 2013;25(1):32–35. doi: 10.1179/1973947812Y.0000000060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar K, Chopra S. New drugs for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an update. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(7):1465–1470. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan N, Garner C, Hafkin B. AFN-1252 in vitro absorption studies and pharmacokinetics following microdosing in healthy subjects. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2013;50(3–4):440–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2013.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan N, Hafkin B. Preclinical Pharmacokinetics and Efficacy of Debio 1450 (Previously AFN-1720), a Prodrug of the Staphylococcal-specific Antibiotic Debio 1452 (Previously AFN-1252) ECCMID 2014. Barcelona, Spain: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan N, Albert M, Awrey D, Bardouniotis E, Berman J, Clarke T, Dorsey M, Hafkin B, Ramnauth J, Romanov V, Schmid MB, Thalakada R, Yethon J, Pauls HW. Mode of action, in vitro activity and in vivo efficacy of AFN-1252, a selective antistaphylococcal FabI inhibitor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:5865–5874. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01411-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlowsky JA, Kaplan N, Hafkin B, Hoban DJ, Zhanel GG. AFN-1252, a FabI inhibitor, demonstrates a staphylococcus-specific spectrum of activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3544–3548. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00400-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J, Maxwell JB, Rock CO. Resistance to AFN-1252 arises from enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase (FabI) missense mutations in Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:36261–36271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.512905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J. Abdelrahman YM, Robertson RM, Cox JV, Belland RJ, White SW, Rock CO. Type II fatty acid synthesis is essential for the replication of Chlamydia trachomatis. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(32):22365–22376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.584185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escalada MG, Harwood JL, Maillard JY, Ochs D. Triclosan inhibition of fatty acid synthesis and its effect on growth of Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55:879–882. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath RJ, Rubin JR, Holland DR, Zhang E, Snow ME, Rock CO. Mechanism of triclosan inhibition of bacterial fatty acid synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11110–11114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerusz V, Denis A, Faivre F, Bonvin Y, Oxoby M, Briet S, LeFralliec G, Oliveira C, Desroy N, Raymond C, Peltier L, Moreau F, Escaich S, Vongsouthi V, Floquet S, Drocourt E, Walton A, Prouvensier L, Saccomani M, Durant L, Genevard JM, Sam-Sambo V, Soulama-Mouze C. From triclosan toward the clinic: discovery of nonbiocidal, potent FabI inhibitors for the treatment of resistant bacteria. J Med Chem. 2012;55:9914–9928. doi: 10.1021/jm301113w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Cummings JE, England K, Slayden RA, Tonge PJ. Mechanism and inhibition of the FabI enoyl-ACP reductase from Burkholderia pseudomallei. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:564–573. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano WL. 2002. ) The PyMOL molecular graphics system on World Wide Web. Version 1.5.0.4 Schrodinger LLC. Accession date 2013. Available at: http://www.pymol.org.

- Schiebel J, Chang A, Shah S, Lu Y, Liu L, Pan P, Hirschbeck MW, Tareilus M, Eltschkner S, Yu W, Cummings JE, Knudson SE, Bommineni GR, Walker SG, Slayden RA, Sotriffer CA, Tonge PJ, Kisker C. Rational design of broad-spectrum antibacterial activity based on a clinically relevant enoyl-ACP reductase inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(23):15987–16005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.532804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge TJ. Structures of gram-negative cell walls and their derived membrane vesicles. J Bacteriol. 1999;181(16):4725–4733. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.16.4725-4733.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmut B, Sandra F, Gregor H, Friederike T. The enoyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] reductase (FabI) of Escherichia coli, which catalyzes a key regulatory step in fatty acid biosynthesis, accepts NADH and NADPH as cofactors and is inhibited by palmitoyl-CoA. Eur J Biochem. 1996;24:689–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0689r.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauls H, Ramnauth J. 2013. ) Salts, prodrugs and polymorphs of FabI inhibitors. WO 2008098374 A1.

- Wiegand I, Hilpert K, Hancock RE. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nature Protoc. 2008;3(2):163–175. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Chong CE, Lim BS, Chai SJ, Sam KK, Mohamed R, Nathan S. Burkholderia pseudomallei animal and human isolates from Malaysia exhibit different phenotypic characteristics. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;58(3):263–70. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Methods in enzymology. Macromolecular crystallography, Part B. Vol. 276. New York: Academic Press; 1997. pp. 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Lokhamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information