Abstract

Metal β-tetrakis(tert-butyl)phthalocyanines are the most commonly used phthalocyanines due to their high solubility, stability, and accessibility. They are commonly used as a mixture of four regioisomers, which arise due to the tert-butyl substituent on the β-position, and to the best of our knowledge, their regioselective synthesis has yet to be reported. Herein, the C4h-selective synthesis of β-tetrakis(tert-butyl)metallophthalocyanines is disclosed. Using tetramerization of α-trialkylsilyl phthalonitriles with metal salts following acid-mediated desilylation, the desired metallophthalocyanines were obtained in good yields. Upon investigation of regioisomer-free zinc β-tetrakis(tert-butyl)phthalocyanine using spectroscopy, the C4h single isomer described here was found to be distinct in the solid state to zinc β-tetrakis(tert-butyl)phthalocyanine obtained by a conventional method.

Keywords: aggregation, phthalocyanines, protecting groups, regioselectivity, silicon, synthesis

Phthalocyanines have gained much attention in recent years due to their potential as organic semiconductors, solar cells, liquid crystals, and medicinal agents.1 Since the first appearance of this macrocycle in 1907,2 a huge number of phthalocyanine derivatives have been synthesized.1 The choice of substituted groups on the peri-positions of phthalocyanines is extremely important to control/alter the fundamental properties of phthalocyanines, such as aggregation states, intense color in the visible range, and thermal and chemical stability.3 Among the variety of substituted phthalocyanines that have been examined, β-tetrakis(tert-butyl)phthalocyanines (1) have been widely investigated because of their chemical robustness, versatility, and high solubility (Figure 1).4 More than 830 papers and patents have been found for 1 by searching for its structure in SciFinder.5a The β-tert-butyl isoindoline moiety has also become a standard A-unit for the synthesis of newly designed unsymmetrical A3B-type phthalocyanines, and more than 1080 compounds have been registered.5b

Figure 1.

β-Tetrakis(tert-butyl)phthalocyanines 1 (mixture) and C4h-1.

Compound 1 can be synthesized by a standard synthetic protocol (Scheme S1 in Supporting Information)6 and is thus obtained as a mixture of four regioisomers, C4h, Cs, D2h and C2v-types (Figure 1). The existence of regioisomers is frequently problematic for spectral characterization and inhibits the formation of a single crystal for X-ray crystallographic analysis. Although these four isomers can be separated by HPLC,7 this task tends to be tedious and sometime even impossible on a practical scale. Consequently, the regoselective synthesis of symmetrical C4h-1 remains one of the longest-standing challenges in phthalocyanine chemistry, despite their very simple structure and ubiquitous usage. Although several approaches for the regioselective synthesis of α-substituted C4h phthalocyanines have been reported,8 reports of the regioselective synthesis of β-substituted phthalocyanines are rare. For example, Leznoff et al. reported that during cyclotetramerizations, the reaction of 3-benzyloxy-phthalonitriles produce the α-substituted C4h phthalocyanines.8g However, the attempt for β-substituted C4h phthalocyanines required a more complex protocol. They achieved the regioselective synthesis of β-substituted 2,9,16,23-tetraneopentoxy-phthalocyanine in 5 % yield by the separation of two regioisomers of the precursor, 1-imino-3-methylthio-6-neopentoxyisoindolenine, following the tetramerization under low reaction temperature at −15 °C for one week.9 Kobayashi et al. achieved the direct D2h selective synthesis of β-substituted phthalocyanine in 2 % yield by using 2,2′-dihydroxy-1L′-binaphthyl linked-phthalonitrile.10

In this context, we hypothesized that sterically demanding C4h β-tetrakis-substituted phthalocyanines should be regioselectively synthesized by assisting the functional group on the α-position. We disclose herein the first regioselective synthesis of metal C4h-tetrakis(tert-butyl)phthalocyanines C4h-1 following the use of α-trialkylsilyl-β-(tert-butyl)phthalonitriles (3) as substrates. The α-trialkylsilyl group effectively controls the regioselective tetramerization of α-trialkylsilyl-β-(tert-butyl)phthalonitriles 3 in the presence of metal ions to corresponding metal C4h phthalocyanines 4,8f and the α-trialkylsilyl moiety on 4 can be easily removed under acid treatment providing C4h-β-tetrakis(tert-butyl)phthalocyanines C4h-1. This approach is found to be general for a range of C4h tetrakis-β-substituted phthalocyanines, including β-methyl and hexyl substituents, and a variety of metal ions such as Zn, Ni, Co and Fe can be accepted as the central metal of phthalocyanines (Scheme 1). The regioisomer-free Zn C4h-β-tetrakis(tert-butyl)phthalocyanine 1 results in very clear 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 1. The UV/Vis and fluorescence spectra of regioisomer-free C4h-1 are disclosed for the first time. These first spectral investigations of C4h-1 have revealed that the UV/Vis spectra of regioisomer-free C4h-1 in solution are as almost the same as the commonly used 1, while these of C4h-1 in the solid state are different from those of conventional 1.

Scheme 1.

Regioselective protocols for the synthesis of C4h-symmetric 1.

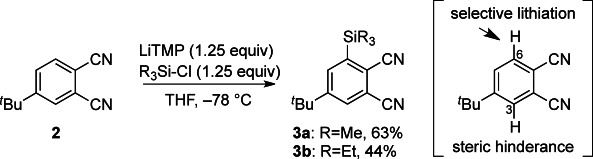

The trialkylsilyl (R3Si) group would be suitable as a sterically demanding α-substituent on the phthalocyanines to control regioselectivity, although its removal should be considered. Thus, the regioselective synthesis of 3 was the first requirement. After optimizing the reaction conditions for the trialkylsilylation of 4-(tert-butyl)phthalonitrile 2, the use of sterically demanding lithium tetramethylpiperidide (LiTMP) was found to be effective for the regioselective ortho-lithiation of 2 followed by silylation with trimethylsilyl chloride or triethylsilyl chloride in tetrahydrofuran at −78 °C, yielding 3 a (63 %) and 3 b (44 %), respectively (Scheme 2). The C6-position was selectively lithiated due to the steric factor between tBu and LiTMP. Other bases such as n-butyllithium and lithium diisopropylamide were not effective for this transformation. Consequently, LiTMP was crucial.

Scheme 2.

Regioselective ortho-lithiation of 2 with LiTMP to provide 3.

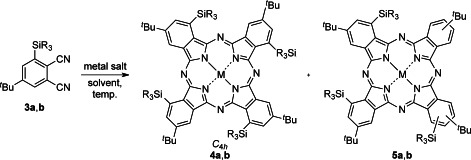

With the key phthalonitriles (3) in hand, the regioselective synthesis of C4h-4 was examined (Table 1). We first attempted the reaction of 3 a under conventional conditions with zinc acetate in N,N-dimethyl-2-aminoethanol (DMAE) at 140 °C. However, a complex mixture of fully to partially desilylated phthalocyanines resulted, due to the desilylation of 3 a into 2 (entry 1, Table 1). The desilylation of 3 a could not be avoided under solvent-free conditions at 230 °C (entry 2, Table 1). Gratifyingly, the use of ethylene glycol as a solvent yielded the desired C4h-4 a (M=Zn) in 29 % yield accompanied with a partially (one) desilylated product, 5 a (M=Zn), in 10 % yield as a mixture of regioisomers (entry 3, Table 1). The C4h-4 a (M=Zn) was also obtained by reaction in 1-chloronaphthalene at 230 °C but the yield decreased to 5.0 % (entry 4, Table 1).

Table 1.

Optimization of reaction conditions for the regioselective synthesis of 4.[a]

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Metal salt | 3 | Solvent | Temp | Yield [%] | |

| [°C] | Compd 4 | Compd 5 | ||||

| 1 | Zn(OAc)2 | 3 a | DMAE | 140 | –[b] | – |

| 2 | Zn(OAc)2 | 3 a | – | 200 | trace | – |

| 3 | Zn(OAc)2 | 3 a | Ethylene glycol | 230 | 29 | 10 |

| 4 | Zn(OAc)2 | 3 a | Chloronaphthalene | 230 | 5 | trace |

| 5 | Ni(OAc)2 | 3 a | Ethylene glycol | 230 | 9.1 | OBc |

| 6 | Ni(OAc)2 | 3 a | Chloronaphthalene | 230 | 1.5 | trace |

| 7 | Co(OAc)2 | 3 a | Ethylene glycol | 230 | –[b] | – |

| 8 | Co(OAc)2 | 3 a | Chloronaphthalene | 230 | 33 | OB[c] |

| 9 | FeCl2 | 3 a | Ethylene glycol | 230 | 11 | 0 |

| 10 | FeCl2 | 3 a | Chloronaphthalene | 230 | trace | – |

| 11 | Cu(OAc)2 | 3 a | Ethylene glycol | 230 | –[b] | – |

| 12 | Cu(OAc)2 | 3 a | Chloronaphthalene | 230 | –[b] | – |

| 13 | Zn(OAc)2 | 3 b | DMAE | 140 | 3.4 | 0 |

| 14 | Zn(OAc)2 | 3 b | – | 200 | 18 | 0 |

| 15 | Zn(OAc)2 | 3 b | Ethylene glycol | 230 | 16 | OB[c] |

| 16 | Zn(OAc)2 | 3 b | Chloronaphthalene | 230 | 1.6 | 0 |

[a] Reagents and conditions: phthalonitrile (1 equiv), metal salt (0.25–0.33 equiv), solvent (0.5–1.0 mL). [b] A mixture of fully to partially desilylated phthalocyanine was observed. [c] OB: 5 b was observed, but it was not fully characterized due to purification difficulties.

We next examined the synthesis of C4h phthalocyanines using other metal salts (entries 5–12, Table 1). Under the best conditions, the metal salts of Ni, Co and Fe yielded corresponding Ni–, Co– and Fe–4 a in 1.5 to 9.1 % yield (4 a–2, M=Ni; entries 5 and 6, Table 1), 33 % (4 a–3, M=Co; entry 8, Table 1) and 11 % (4 a–4, M=Fe; entry 9, Table 1), respectively, with detectable amounts of fully to partially desilylated 5 a (M=Ni, Co). C4h phthalocyanines having copper as a central metal could not be obtained under the same reaction conditions (entries 11–12, Table 1). Only 1-chloronaphthalene as the solvent was effective for the preparation of C4h Co–phthalocyanine 4 a–3 (entry 8, Table 1).

Compound 3 b was next investigated for the macrocyclization reaction (entries 13–16, Table 1). Interestingly, the desired C4h-4 b (M=Zn) having a triethylsilyl group at the α-position was produced in all cases with 1.6 to 18 % yields. The formation of a partially desilylated product (5 b) was suppressed due to the higher thermal stability of the triethylsilyl group than the trimethylsilyl group, except that the reaction took place in ethylene glycol. It should be noted that in all cases, no detectable amounts of the other possible regioisomers of 4 a,b, that is, Cs, D2h and C2v-types, were formed.

Next, we applied this methodology for the regioselective synthesis of C4h symmetric phthalocyanines having other alkyl groups at the β-position (Scheme 3). At first, 3-(trimethylsilyl)phthalonitriles with a methyl or hexyl group at the β-position 6 a,b were synthesized by regioselective ortho-lithiation of 7 a,b using LiTMP followed by trimethylsilylation in 33 % and 65 % yields, respectively. 6 a,b were treated with zinc acetate in ethylene glycol at 230 °C affording desired C4h-8 a,b in 14 to 15 % yields, respectively. Desilylated analogues 9 a,b were also produced in 12 % yield as a mixture of regioisomers.

Scheme 3.

Regioselective synthesis of other symmetric C4h phthalocyanines.

In order to discuss the high C4h regioselectivity achieved by our methodology, a computation was attempted next. Hanack reported that the regioselectivity of the formation of phthalocyanines depends on the difference in reactivity between two cyano groups of phthalonitrile.8c Hence, the charge distributions of two cyano groups on 3 a and 3 b were calculated (DFT/B3LYP/6-31G*) (Figure 2 a). In 3 a, the charge distribution of the cyano group next to the trimethylsilyl group was almost the same as another cyano group (0.269 (C2) vs 0.256 (C1)), which indicates that their reactivity is similar. On the other hand, the charge distribution of each cyano group in 3 b is rather different (0.405 (C2) versus 0.234 (C1)). These computed results suggest that the regioselectivity of 3 b should be higher than that of 3 a. However, the experimental results of the regioselectivity by 3 a and 3 b are the same. Therefore, the regioselectivity of the observed reaction is presumably caused by the steric effect of the trialkylsilyl group (B≫>B′), while the electronic effect is supplemental (A>A′) (Figure 2 b). The steric repulsion between two neighboring trialkylsilyl units on dimer units is the main role for the selectivity. This should be the main reason for the success of the regioselective tetramerization even under very high reaction temperature, while the methodology by Leznoff requires very low reaction temperature due to the reactivity controlled between two cyano groups.9

Figure 2.

a) Charge distribution of CN groups of 3. b) A proposed reaction mechanism.

The symmetric C4h-4 a (M=Zn) was easily converted into the target C4h-1 (M=Zn) in concentrated sulfuric acid at room temperature in 69 % yield. Desilylation of 5 a was also attempted under the same conditions to afford 1 as a mixture of regioisomers in 70 % yield (Scheme S2 in the Supporting Information).

As expected, the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of C4h-1 were very different from those of the authentic sample of 1 synthesized by a conventional method. The assignable peaks of 1H and 13C NMR spectra of C4h-1 are expectedly simple, while those of conventional 1 are complicated (Figure S1 in Supporting Information). The UV/Vis and fluorescence spectra of C4h zinc β-tetrakis(tert-butyl)phthalocyanine 1 were compared with those of 1 prepared by a conventional method in dichloromethane. They appear similar, independent of the regioisomers. These spectra show that the position of the tert-butyl group on phthalocyanine does not influence the optical properties of 1 in solution (Figure 3).7a On the other hand, using a different method such as optical waveguide spectroscopy, the UV/Vis attenuated total reflection (ATR) spectra of C4h-1 thin films were found to be different from those of conventional 1 thin films (Figure 4). Q-Bands of conventional 1 as thin films are 8 nm red-shifted from those of solution state, and bands of C4h-1 are 11 nm red-shifted from those of solution state (1: 678 nm in CH2Cl2; 686 nm in thin film; C4h-1: 678 nm in CH2Cl2; 689 nm in thin film).

Figure 3.

a) Comparisons between UV/Vis spectra of C4h-1 (green: 1.0×10−5 m) and conventional 1 (purple: 1.0×10−5 m) in dichloromethane. b) Comparison of fluorescence spectra of C4h-1 (green) and conventional 1 (purple) in dichloromethane.

Figure 4.

Comparisons between UV/Vis attenuated total reflection (ATR) spectra of C4h-1 of thin film (green: s-polarized light; light green: p-polarized light), conventional 1 of thin film (blue: s-polarized light; light blue: p-polarized light) and C4h-1 in dichloromethane (red: 1.0×10−5 m).

This phenomena could be induced by their J-aggregation, although these shifts are not significant.11 Namely, 1 and C4h-1 are aggregation-free in solvents, however, they are J-aggregated as solid states. As can be seen in the red-shifted length, C4h-1 seems to be more aggregated than 1. The spectrum of C4h-1 is much broader than that of conventional 1, besides, both of them are blue-shifted by comparison with their solution spectra. In particular, the absorption band of C4h-1 around 630 nm is stronger and broader than that of 1, which is highly related to the vertical interaction in C4h-1. These observations should indicate H-aggregation, and C4h-1 aggregates more strongly than conventional 1, which is a mixture of regioisomers.12 More interestingly, the differences in UV/Vis ATR spectra of conventional 1, obtained using p-polarized light and s-polarized light, are greater than those of C4h-1. This fact indicates that the aggregation state of conventional 1 on the surface is consistent (i.e., J-aggregation), while that of C4h-1 is rather random (i.e., J and H-aggregation).13 These aggregation differences in solid states can be explained as follows: C4h-1 is a single isomer and the vertical interaction of C4h-1 via π–π stacking is allowable, while the same interactions in conventional 1 are rather difficult due to the steric repulsion of regioisomers. Consequently, both J-aggregation and H-aggregation are allowed in the surface of C4h-1, while conventional 1 predominantly exists in J-aggregation.

In conclusion, we have achieved the regioselective synthesis of C4h-tetrakis(tert-butyl)metallophthalocyanines for the first time. The key for this transformation is the dual use of steric effects of the trialkylsilyl group in regioselective ortho-lithiation/silylation and tetramerization. The trialkylsilyl group can be removed by acid treatment in good yield. The NMR spectra of C4h-1 revealed its high symmetry. It should be mentioned that the UV/Vis ATR spectra of C4h-1 and conventional 1 in solution are almost the same, and they are even superimposable, while in the thin film, they are different and far from superimposable. In solution, both C4h-1 and conventional 1 exist as nonaggregates. In thin films, C4h-1 has a tendency towards random orientation with H- and J-aggregation, while conventional 1 seems to indicate only J-aggregation. Although there might be other interpretations of these spectral differences in a film state, the work reported here represents the first synthesis and spectral investigation of regioisomer-free C4h-tetrakis(tert-butyl)metallophthalocyanines 1. Since tetrakis(tert-butyl)metallophthalocyanines 1 are among the most popular phthalocyanines, C4h-1 should be useful for their precise characterization of the aggregation state, and the design of novel materials such as dye-sensitized solar cells. An extension of this methodology for the synthesis of a variety of β-functionalized phthalocyanines is under way.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported in part by the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) through their Platform for Drug Discovery, Informatics, & Structural Life Science, and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) through their Scientific Research (B) grant 25288045 and Exploratory Research grant 25670055. N.I. thanks the Hori Science and Arts Foundation (Japan) for support.

Supporting Information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re-organized for online delivery, but are not copy-edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

References

- 1a.Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R, editors. Handbook of Porphyrine Science, Vol. 30–35. New York: Academic Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 1b.Sorokin AB. Chem. Rev. 2013;113:8152–8191. doi: 10.1021/cr4000072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1c.Bottari G, de La Torre G, Guldi DM, Torres T. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:6768–6816. doi: 10.1021/cr900254z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1d.de La Torre G, Claessens CG, Torres T. Chem. Commun. 2007:2000–2015. doi: 10.1039/b614234f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braun A, Tcherniac J. Chem. Ber. 1907;40:2709–2714. [Google Scholar]

- 3a.Kobayashi N, Ogata H, Nonaka N, Luk′yanets EA. Chem. Eur. J. 2003;9:5123–5134. doi: 10.1002/chem.200304834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3b.Leznoff CC, Lever ABP, editors. Phthalocyanines: Properties and Applications, Vol. 1. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 1989. pp. 27–54. [Google Scholar]

- 4a.Perry JW, Mansour K, Lee I-YS, Wu X-L, Bedworth PV, Chen C-T, Ng D, Marder SR, Miles P, Wada T, Tian M, Sasabe H. Science. 1996;273:1533–1536. [Google Scholar]

- 4b.Palomares E, Martínez-Díaz MV, Haque SA, Torres T, Durrant JR. Chem. Commun. 2004:2112–2113. doi: 10.1039/b407860h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4c.Lim B, Margulis GY, Yum J-H, Unger EL, Hardin BE. Org. Lett. 2013;15:784–787. doi: 10.1021/ol303436q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a. A result by SciFinder substructure search (search type: “substructure”) using 2,9,16,23-tetrakis(tert-butyl)phthalocyanine;

- 5b. A result by SciFinder substructure search using 2,9,16-tris(tert-butyl)phthalocyanine.

- 6.de La Torre G, Claessens CG, Torres T. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2000:2821–2830. [Google Scholar]

- 7a.Sommerauer M, Rager C, Hanack M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:10085–10093. [Google Scholar]

- 7b.Görlach B, Dachtler M, Glaser T, Albert K, Hanack M. Chem. Eur. J. 2001;7:2459–2465. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20010601)7:11<2459::aid-chem24590>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8a.Leznoff CC, Hu M, Nolan KJM. Chem. Commun. 1996:1245–1246. [Google Scholar]

- 8b.Kasuga K, Asano K, Lin L, Sugimori T, Handa M, Abe K, Kikkawa T, Fujiwara T. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1997;70:1859–1865. [Google Scholar]

- 8c.Rager C, Schmid G, Hanack M. Chem. Eur. J. 1999;5:280–288. [Google Scholar]

- 8d.Kasuga K, Kawashima M, Asano K, Sugimori T, Abe K, Kikkawa T, Fujiwara T. Chem. Lett. 1996;25:867–868. [Google Scholar]

- 8e.Sugimori T, Okamoto S, Kotoh N, Handa M, Kasuga K. Chem. Lett. 2000;29:1200–1201. [Google Scholar]

- 8f.Chen MJ, Rathke JW, Sinclair S, Slocum DW. J. Macromol. Sci., Part A: Pure Appl. Chem. 1990;27:1415–1430. [Google Scholar]

- 8g.Hu M, Brasseur N, Yildiz SZ, van Lier JE, Leznoff CC. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:1789–1802. doi: 10.1021/jm970336s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenberg S, Lever ABP, Leznoff CC. Can. J. Chem. 1988;66:1059–1064. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi N, Kobayashi Y, Osa T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:10994–10995. [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Kasha M, Rawls HR, Ashraf El-Bayoumi M. Pure Appl. Chem. 1965;11:371–392. [Google Scholar]

- 11b.Isago H. Chem. Commun. 2003:1864–1865. doi: 10.1039/b304089e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11c.Okada S, Segawa H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:2792–2796. doi: 10.1021/ja017768j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12a.Kobayashi N, Lever ABP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:7433–7441. [Google Scholar]

- 12b.Nevin WA, Liu W, Lever ABP. Can. J. Chem. 1987;65:855–858. [Google Scholar]

- 12c.Isago H, Leznoff CC, Ryan MF, Metcalfe RA, Davids R, Lever ABP. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1998;71:1039–1047. [Google Scholar]

- 13a.Eguchi M, Tachibana H, Takagi S, Tryk DA, Inoue H. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2007;80:1350–1356. [Google Scholar]

- 13b.Eguchi M, Watanabe Y, Shimada T, Takagi S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014;55:2662–2666. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary