Abstract

Disease related antigens are of great importance in the clinic. They are used as markers to screen patients for various forms of cancer, to monitor response to therapy, or to serve as therapeutic targets (Chapman et al., Ann Oncol 18(5):868–873, 2007; Soussi et al., Cancer Res 60:1777–1788, 2000; Anderson and LaBaer, J Proteome Res 4:1123–1133, 2005; Levenson, Biochim Biophy Acta 1770:847–856, 2007). In cancer endogenous levels of protein expression may be disrupted or proteins may be expressed in an aberrant fashion resulting in an immune response that bypasses self tolerance (Soussi et al., Cancer Res 60:1777–1788, 2000; Disis et al., J Clin Oncol 15(11):3363–3367, 1997; Molina et al., Breast Cancer Res Treat 51:109–119, 1998). Protein microarrays, which represent a large fraction of the human proteome, have been used to identify antigens in multiple diseases including cancer (Anderson and LaBaer, J Proteome Res 4:1123–1133, 2005; Disis et al., J Clin Oncol 15(11):3363–3367, 1997; Hudson et al., Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104(44):17494–17499, 2007; Beyer et al., J Neuroimmunol 242:26–32, 2012). Typically, arrays are probed with immunoglobulin (Ig) samples from patients as well as healthy controls, then compared to determine which antigens (Ag's) are more reactive within the patient group (Hudson et al., Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104(44):17494–17499).

Keywords: Protein microarray, Detection antibody, Immunoglobulin, Cancer antigen, Serum, Fluorescent dye, Nitrocellulose, Quantile normalization

1 Introduction

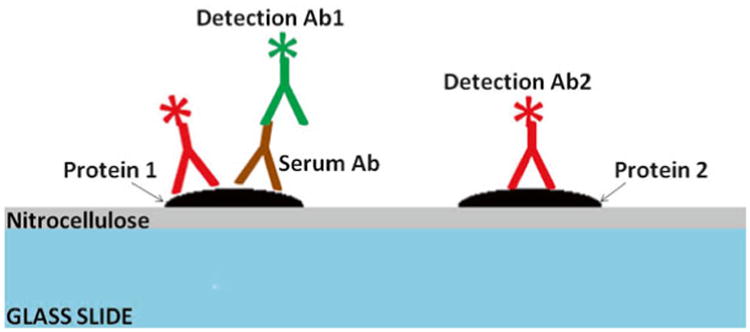

Protein arrays have become a standard method for assaying interactions of biomolecules on a broad scale. Originally developed to screen protein–protein interactions and enzyme activity [1], these arrays have become standard tools for detecting disease specific antibody (Ab)–antigen interactions in various disease states [2, 3, 4, 5]. Other screening methods like SEREX (serological analysis of cDNA expression libraries) or 2-D PAGE require additional steps to identify the antigens and suffer from poor reproducibility [6]. This is not the case with protein microarrays as each spot is individually addressable and hundreds of arrays can be produced in the same lot resulting in high degree of uniformity. Most of these arrays are made by printing individually purified proteins or lysates onto glass slides that have been coated with nitrocellulose (FAST and PATH arrays) (Fig. 1). Other surface chemistries are used and different spotting methods such as NAPPA (nucleic acid programmable protein arrays) have been demonstrated as well [7]. The resolution of these arrays is only limited by the feature size (∼100 μM diameter for spots on printed arrays) and the number of spots that can be printed on them.

Fig. 1.

Cross-sectional diagram of a typical protein array that has been probed with an Ig sample and fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies to the Ig and common epitopes of the arrayed proteins. The glass surface of the array is shown in blue and the nitrocellulose surface coating in gray. Proteins are represented in black. Bound Ig's are depicted in brown, while the anti-Ig detection antibodies are green and the anti-epitope detection antibodies in red. There is a serum response to the protein on the left, while the protein to the right is not reactive with Ig's in the sample. Both proteins are recognized by the anti-epitope detection antibody as both contain the same fusion tag (e.g., GST)

Currently, some commercial arrays feature more than 9,000 full length human proteins (approximately one-third of the proteome) and arrays that represent the entire proteome are expected in the near future. Traditionally there have been three categories of protein microarray: (1) functional arrays, (2) lysate arrays, and (3) capture arrays. Functional protein arrays are printed using full-length proteins or large domains of proteins that retain their native functional activity [1]. Lysate arrays contain gross cellular lysates rather than individually expressed and purified proteins. The last category of arrays, capture or antibody arrays, are printed with antibodies that are meant to bind and pull down targeted proteins in a sample that can then be detected using a specific secondary antibody much like an enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) [8]. Proteins that are used in preparation of functional arrays are often produced using a baculovirus system in insect cells (sf9 cells) and include an epitope tag, such as GST, to facilitate purification [2]. One drawback to using proteins expressed in such a system for evaluating human self antigen responses is that they may not display normal levels of posttranslational modifications. Thus, a serum response that is directed against modified residues may be overlooked [9, 2].

Recently, photochemical printing of peptides has caught up to that of their nucleotide microarray counterparts as high throughput sequencing has replaced such arrays and whole proteome arrays can now be produced. Roche is currently developing such an array that will tile the entire proteome at a resolution using overlapping peptides. The resolution is important for epitope mapping (complimentary determining regions of antibodies bind to epitopes of approximately six amino acids). While peptide arrays offer the highest density, there is the disadvantage that some binding interactions that require native protein conformation may not be observed [9, 2, 1].

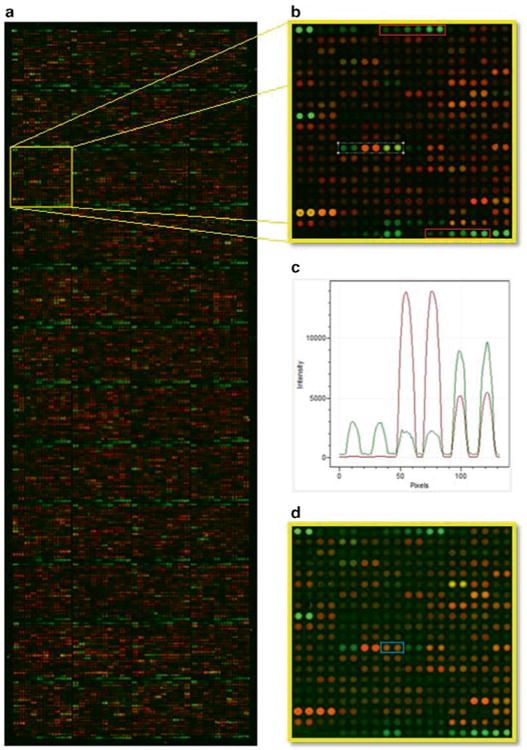

Cancer antigens have demonstrated incredible importance in the clinic for screening and as prognostic indicators [10, 11, 9, 12]. The experimental design for identifying novel antigens using protein arrays often involves probing the arrays with sera or other body fluids (e.g., synovial fluid, cerebrospinal fluid, or sputum) that contain Ig's that may recognize epitopes of antigens spotted or printed on the arrays. Typically, the arrays are incubated with an appropriate dilution of the Ig (empirically determined) from a diseased group as well as from an age/sex-matched healthy donor group. The arrays are then washed to remove unbound Ig and incubated again with a secondary detection antibody that has been conjugated to a fluorescent dye. Image data is then collected by scanning the arrays using a fluorescent scanner (Fig. 2). Differences in antigen reactivity between the patient and control groups can then be determined. However, this oversimplifies the roles that data normalization and analysis play in these studies. Protein microarrays suffer from greater artifacts and increased background compared to nucleic acid microarrays and since many cancer antigens may show only subtle differences in reactivity it is necessary to normalize to account for artifacts that may obscure those antigens [2]. Effective statistical methods have been developed to smooth away regional artifacts and quantile normalization often is conducted prior to statistical comparison of the two groups [2, 13]. It is often desirable to screen a smaller cohort of patients using more costly high density arrays in order to identify candidate self antigens. These markers may then be validated by screening many more patients for reactivity using more focused assays, as this approach can be more cost-effective and higher throughput. Histological methods such as immunohistochemical (IHC) staining are often employed to validate candidate cancer antigens identified in protein array screens [2].

Fig. 2.

Panel a shows a protein microarray with 9,000+ full length GST tagged human proteins spotted in duplicate that was probed with sera from a patient with multiple myeloma. Human IgG signals were detected with an Alexa Fluor 555 anti-human IgG secondary antibody and GST-protein content was detected with an Alexa Fluor 647 anti-GST antibody. IgG signal is shown in green and GST in red. The yellow highlighted block is shown in panel b. IgG and GST reactive protein antigens are visible and dilution series of human IgG and anti- human IgG capture antibodies are shown in red blocks. Reactivity profiles of the antigens in the white block are shown in panel c. Spot reactivity is shown in order from left to right. Panel d shows the same block from a corresponding array that was probed with sera from a healthy individual. An antigen that shows differential reactivity from the myeloma serum probing is shown in the blue block

2 Materials

All buffers are prepared using molecular biology grade H2O. Arrays are typically probed in batches of 20 per day over a period of 4–6 days (80–120 arrays are usually printed in a lot). A 10 % excess of each buffer is prepared and cooled to 4 °C at the start of the procedure each day. If probing a different number of arrays, the buffer volumes that are prepared may be scaled accordingly.

Blocking buffer: using a graduated cylinder prepare 110 mL to a final concentration of 50 mM HEPES, 200 mM NaCl, 0.08 % Triton X-100, 25 % glycerol, 20 mM glutathione (reduced), and 1× synthetic block (Life Technologies Inc. catalogue # PA017) (see Note 1). Then adjust the pH to 7.5 using a 4 M NaOH solution and add water to a final volume of 110 mL (see Note 2). Finally, add DTT to 1 mM just prior to blocking the arrays.

Wash buffer: prepare by making a 1× PBS (pH = 7.4), 1× synthetic block, and 0.1 % Tween-20 solution in a final volume of 1,500 mL using a graduated cylinder (see Note 3).

Patient samples: store human plasma/serum at −80 °C and avoid multiple freeze–thaw cycles. Prepare dilutions on ice with wash buffer within 2 h of probing the arrays.

Secondary detection reagents: Alexa Fluor-555 coupled highly anti-human IgG may be purchased commercially. Alexa Fluor 647 coupled anti-GST is also commercially available (see Note 4).

3 Methods

Always be cautious when working with human plasma or sera, take appropriate precautions and wear personal protective equipment (e.g., lab coat, latex gloves, and goggles). Be sure to become trained in laboratory safety involving bloodborne pathogens as well as general personal safety protocol. This protocol is adapted from our original Protometrix protocols and Invitrogen's Protoarray IRBP protocol and is appropriate for immune response profiling using all FAST/PATH based protein microarrays (i.e., nitrocellulose coated glass slide based arrays).

Thaw arrays: Remove arrays from freezer and place in a 4 °C cold room (remainder of protocol up to the water rinse step will be carried out at 4 °C). Allow the arrays to equilibrate for up to 30 min (see Note 5). Then remove the arrays using forceps or tweezers. Place the arrays into a four-well slide culture tray (see Note 6).

Incubate the arrays with blocking buffer: Add 5 mL of blocking buffer to each well. Gently tilt the trays back and forth until the blocking buffer covers the entire surface of each array. Incubate with gentle shaking (<100 rpm) on a circular shaker for 1 h (see Note 7). Remove the blocking buffer completely. Quickly proceed to the next step to avoid drying of the array surface (see Note 8).

Rinse the arrays with wash buffer: Add 5 mL of washing buffer to each well. Incubate with shaking as above. After 5 min remove the buffer completely and proceed immediately to the next step (see Note 9).

Serum incubation: Thaw all serum samples on ice. Clarify the serum samples by spinning in a microcentrifuge at 20,000 × g (or maximum speed) for 10 min at 4 °C. Dilute serum into 5 mL of wash buffer. Dispense 5 mL of diluted serum into each well (one negative control slide may be incubated with 5 mL of wash buffer without serum). Incubate for 1.5 h with shaking as before (see Note 10).

Wash the arrays: Aspirate the samples from each well. Add 5 mL of wash buffer to the wells and incubate for 5 min with shaking. Repeat the wash four more times (see Note 11).

Incubate the arrays with secondary detection antibodies: Dilute fluorescently labeled anti-human Ig secondary detection antibody in wash buffer. Add 5 mL of the diluted antibody to each well. Incubate arrays with the detection antibody for 1.5 h with rocking at 4 °C in the dark (see Note 12).

Wash the arrays: Aspirate the samples from each well. Add 5 mL of wash buffer to the wells and incubate for 5 min with shaking. Repeat the wash step four more times (see Note 13). Do not aspirate the buffer after the final wash.

Water rinse: Prepare a beaker with a sufficient volume of molecular biology grade H2O to fully submerge the full length of the arrays. Gently submerge the arrays in the water bath (see Note 14). This step should be performed at room temperature. Proceed immediately to drying of the arrays.

Drying of the arrays: Dry the arrays by placing them into a light block slide box and spinning them at 200 × g for 2 min in a swinging bucket type centrifuge with plate adaptor at room temperature (see Note 15). Allow the slides to stay at room temperature in the slide boxes overnight before scanning (see Note 16).

Data collection: Scanning of the arrays should be performed within 24 h of probing. Scanner should be properly calibrated prior to scanning. All scanner settings should remain the same while scanning the arrays (see Note 17).

Data processing and analysis may be conducted using standard techniques (see Note 18).

4 Notes

Life Technologies offers a premade blocking buffer that can also be used when working with PATH based arrays. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) or Hammerstein casein, at a final concentration of 10 mg/mL, may be substituted for the synthetic blocking agent. Filter the solution using a 500 mL, 0.2 μm vacuum filter unit. This helps to reduce debris that can bind to the arrays increasing background. Take care to avoid foaming of the buffer during filtration (adding the Triton X-100 after filtering can help). It is convenient to prepare a 10 % solution of triton X-100 for use in making the buffer. If the arrays are to be printed in house, or if it is desirable to include additional antigens, purified or commercially purchased antigens may be mixed 50/50 volume/volume with blocking buffer (minus reduced glutathione, blocking agent, and DTT) and spotted onto the array's surface using a manual or automated slide printer.

The need to adjust the pH manually may be avoided by using commercial stock solutions of HEPES that has already been pH adjusted. If adjusting pH manually, care should be taken when near the desired pH not to surpass it by switching to a 1 M NaOH solution.

A 10× PBS stock solution that is already adjusted to pH = 7.4 may be purchased from many commercial vendors. A 10 % Tween-20 solution should be prepared in advance. Again, other blocking agents (i.e., BSA or casein) may be substituted for the synthetic block. A synthetic blocking reagent has the advantage of a known composition resulting in improved reproducibility. This buffer may be filtered using a 0.2 μm vacuum filter unit.

Secondary antibodies should be polyclonal and Alexa Fluor dyes are preferable to Cy dyes as the latter are more sensitive to photodamage.

While transporting arrays, keep the containers they are in on ice. Arrays should be kept in sealed slide boxes or slide mailers to avoid exposure to air or moisture until they reach ambient temperature in the cold room. It is important not to remove the arrays from their containers until they are the same temperature as the surrounding air to avoid precipitation from forming on the array surface.

Avoid touching the protein containing regions of the array. It is best to handle the arrays from the barcoded end (or the end furthest from the proteins). It is also critical that the arrays be oriented such that the side containing the spotted proteins is facing up in the trays.

This step serves to block nonspecific interactions and reduces background (similar to blocking a membrane with blotto in western blotting). Blocking buffer should be dispensed against the sides or corners of the wells, not directly onto the surface of the arrays as this may disrupt or damage the protein spots. The trays may be stacked on top of each other during rocking steps to assure that all of the arrays are shaken at the same speed and orientation.

It is preferable to vacuum aspirate the buffer using a pipette tip (it may be necessary to clip the tip or use a tip with a wide bore as the blocking buffer contains glycerol and is highly viscous). To effectively remove the buffer it helps to slightly tilt the trays.

This step serves to remove any remaining blocking buffer. If the amount of sample available will not be enough for performing the incubations in 5 mL after dilution in wash buffer, then the slides may be removed from the trays and incubated using other means that are compatible with small volumes. Slides may be removed to new four-well incubation trays by gently prying up the slide using the tips of the tweezers. Only lift the slides from the barcoded end or the end furthest from the protein content.

Serum is usually diluted between 1:150 and 1:500. It is helpful to prepare the diluted serum in advance during the blocking step by dispensing 5 mL of wash buffer for each sample into a 14 mL Falcon tube on ice and diluting the sera into these tubes. Cap each tube and mix by inverting the tubes several times. Care should be taken when adding the samples to the wells and during shaking so as not to cross contaminate the adjacent wells.

The pipette tip should be changed each time when aspirating the samples before the first wash step to avoid cross contamination. After this the same tip may be used to aspirate wash buffer. Do not tilt the trays to aspirate the samples from the wells as this could result in cross contamination of wells.

It is important to shield the secondary antibodies from light to prevent photodamage to the fluorescent labels. If the lights in the cold room cannot be turned off during the 90 min incubation step, the trays may be covered with tinfoil. Fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies to various Ig isotypes (e.g., IgG, IgM, and IgA) are commercially available. Also, Molecular Probes carries a number of kits for labeling secondary Ab's with Alexa Fluor dyes if there is no commercially available secondary Ab to a particular isotype or species of interest. It may be useful to include an additional secondary detection antibody that has a different excitation and emission spectra than the first as a control. This antibody may recognize an epitope tag on the arrayed proteins to aid in data collection and analysis. For example, Alexa Fluor 647 anti-human IgG may be combined with Alexa Fluor 555 anti-GST if the proteins on the array were GST purified. Secondary detection antibodies are usually diluted 1:2,000 in wash buffer. Secondary antibodies must be prepared fresh each day. It is convenient to dilute the detection antibodies during step 5 above. After dilution secondary Ab's should be kept in the dark.

It is not necessary to change pipette tips during this wash cycle.

This step improves the signal to noise ratio by removing background caused by compounds in the buffer (e.g., salts and detergent) and unbound secondary antibody. Arrays may be submerged two to four times each (be consistent in the treatment of each array). It is convenient and more consistent to submerge all of the arrays that have been probed in a batch at the same time by placing them into a slide rack and submerging the entire rack.

This step helps to remove H2O that would otherwise dry on the array surface leaving areas of high background. The slide boxes should be lined with filter paper or Kimwipes to absorb excess moisture.

The overnight incubation is important to assure that there is no additional moisture on the arrays prior to scanning. The arrays may be placed at 4 °C after scanning for storage if it is important to rescan the arrays (Alexa Fluor dyes remain stable for over multiple scans).

Molecular devices' scanners are commonly used for scanning FAST/PATH based arrays. PMT settings should be determined by scanning one randomly selected array. Settings must be chosen such that the images display a dynamic range of high and low signals and the same settings should be used for scanning all of the arrays that will be compared. If two secondary antibodies were used, ratio data may also be collected. This is much like array co-genome hybridization (CGH) with nucleic acid arrays.

Normalization and statistical comparison methods that have been used for nucleotide based microarrays are often employed for analyzing protein arrays data. Common statistical methods of comparison include Mann–Whitney U-test, Student's T-test, and M-statistic, in order to determine which antigens are statistically differentially reactive between the two groups [2].

References

- 1.Ptacek J, et al. Global analysis of protein phosphorylation in yeast. Nature. 2005;438(7068):679–684. doi: 10.1038/nature04187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hudson M, et al. Identification of differentially expressed proteins in ovarian cancer using high-density protein microarrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(44):17494–17499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708572104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beyer N, et al. Investigation of autoantibody profiles for cerebrospinal fluid biomarker discovery in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2012;242:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen R, et al. Personalized omics profiling reveals dynamic molecular and medical phenotypes. Cell. 2012;148:1293–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu H, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome diagnostics using a coronavirus protein array. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(11):4011–4016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510921103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scanlan M, et al. Humoral immunity to human breast cancer: antigen definition and quantitative analysis of mRNA expression. Cancer Immun. 2001;1:4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qiu J, et al. Nucleic acid programmable protein array a just-in-time multiplexed protein expression and purification platform. Methods Enzymol. 2011;500:151–163. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385118-5.00009-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlsson A, et al. Serum proteome profiling of metastatic breast cancer using recombinant antibody microarrays. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:472–480. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molina R, et al. c-erbB2 oncoprotein, CEA, and CA 15.3 in patients with breast cancer: prognostic value. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998;51:109–119. doi: 10.1023/a:1005734429304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levenson V. Biomarkers for early detection of breast cancer: what, when, and where? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1770:847–856. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Disis M, et al. High-titer HER-2/neu protein-specific antibody can be detected in patients with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(11):3363–3367. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.11.3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho W. Contribution of oncoproteomics to cancer biomarker discovery. Mol Cancer. 2007;6(25):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu X, et al. ProCat: a data analysis approach for protein microarrays. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R110. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-11-r110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]