Abstract

Peroxiredoxin-6 (PRDX6) is an unusual member of the peroxiredoxin family of antioxidant enzymes that has only one evolutionarily conserved cysteine. It reduces oxidized lipids and ROS by oxidation of the active site cysteine (Cys-47) to a sulfenic acid, but the mechanism for conversion back to a sulfhydryl is not completely understood. Moreover, it has a phospholipase A2 activity in addition to its peroxidase activity. Interestingly, some biochemical data are inconsistent with a known high-resolution crystal structure of the catalytic intermediate of the protein, and biophysical data indicate the protein undergoes conformational changes that affect enzyme activity. In order to further elucidate the solution structure of this important enzyme, we used chemical cross-linking coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry (CX-MS), with an emphasis on zero-length cross-links. Distance constraints from high confidence cross-links were used in homology modeling experiments to determine a solution structure of the reduced form of the protein. This structure was further evaluated using chemical cross-links produced by several homo-bifunctional amine-reactive cross-linking reagents, which helped confirm the solution structure. The results show that several regions of the reduced version of human PRDX6 are in a substantially different conformation from that shown for the crystal structure of the peroxidase catalytic intermediate. The differences between these two structures are likely to reflect catalysis-related conformational changes. These studies also demonstrate that CX-MS using zero-length cross-linking is a powerful strategy for probing protein conformational changes that is complementary to alternative methods such as crystallographic, NMR, and biophysical studies.

Regulation of oxidative stress is an important problem in the maintenance of cellular homeostasis. The presence of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and their by-products can have multiple deleterious effects on cells. The lung is particularly vulnerable to these effects, due to its continual exposure to oxidants via ambient air as well as its extensive capillary networks [1]. Oxidative damage has been notably associated with various disease states in the lung, ranging from acute lung injury (ALI) to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [2, 3]. In order to protect against oxidative injury, eukaryotic cells express a number of anti-oxidative stress proteins. Among these is a family of proteins known as peroxiredoxins. Peroxiredoxins differ from others involved in similar functions by working in conjunction with thiol-containing electron donor molecules, as opposed to using redox cofactors or prosthetic groups [4, 5]. Most peroxiredoxins employ two conserved Cys residues in a disulfide bond as their electron donor group in the presence of a reductant, typically thioredoxin. This is known as a 2-Cys mechanism [4,5].

Peroxiredoxin-6 (PRDX6) is a unique case in the peroxiredoxin family. It is a homo-dimeric enzyme found in mammals, particularly mammalian lungs [6], that features at least two distinct enzymatic activities – the reducing property common to all peroxiredoxins, as well as phospholipase A2 (PLA2) via a conserved catalytic triad (His-26, Ser-32, Asp-140) [7, 8], It is also the only peroxiredoxin with the reported ability to reduce phospholipid hydroperoxides [9]. Moreover, PRDX6 does not feature the two canonical Cys residues that are the hallmark of most members of the peroxiredoxin family. Only one cysteine, Cys-47, is conserved across species, and its peroxidase activity is therefore described as a 1-Cys mechanism that involves oxidation of Cys-47 to a sulfenic acid as a peroxidase catalytic intermediate. The enzymatic cycle is completed by reduction of the active site back to a sulfhydryl by glutathione in conjunction with glutathione S-transferase [10, 11]. PRDX6’s PLA2 activity is regulated by phosphorylation of a Thr-177 residue, indicating that activation of the PLA2 activity involves a conformational change [12, 13]. Both the PLA2 as well as the phospholipid hydroperoxide activities require conformational specificity in the binding of the enzyme to the phospholipid substrate [14].

A high-resolution crystal structure for human PRDX6 has been reported (PDB ID: 1PRX), but in order to obtain this structure it was apparently necessary to mutate a non-conserved cysteine (Cys-91) and oxidize the active site cysteine to the sulfenic form [15]. Perhaps because the active site is in the catalytic intermediate state, the crystal structure does not appear to accurately reflect the solution structure of the reduced form of the protein. For example, a recent study showed that Thr-177, which is totally buried in the crystal structure, can be phosphorylated, indicating solvent exposure under conditions that should include the conformation in solution of the protein with Cys-47 in the reduced state [12, 13]. This phosphorylation induces a further conformational change that increases PLA2 activity and affinity for liposomes. Other biochemical data indicate that the protein undergoes conformational changes that can modulate enzyme activity, such as the conformational change that results in protein activation when binding with glutathione-S-transferase (GST) [11] and the one that occurs upon binding to the phospholipid head group [8]. Considering the substantial conformational flexibility of the protein and importance of conformational changes on both enzyme activities, elucidation of the solution structure of the reduced form of the enzyme is needed.

We combined chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry (CX-MS) in order to determine distance restraints for testing and refinement of homology models of PRDX6. CX-MS has been shown to be a powerful method to distinguish between alternative predicted conformations of a protein and to refine predicted structures to highly accurate levels when using homology modeling [16]. The utility of this approach has been demonstrated in many studies including recent analyses of diverse macromolecular systems [17–19].

Our group has recently optimized the use of cross-linkers with no spacer arms between the cross-link reactive sites (also known as zero-length cross-linkers) because such cross-links define the most stringent distance constraints [20–23] Typically, these reactions use the zero-length cross-linking reagent 1-ethyl-3-(-3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC), which is used in conjunction with sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinimide (sulfo-NHS). Cross-links are formed between carboxylic acids (Asp and Glu side chains and the protein C-terminus) and primary amines (Lys side chains and the protein N-terminus). Because no extra atoms are contributed by the cross- linking reagents, the atoms that contribute to the cross-link need to be within salt bridge distance. [24] Zero-length cross-linked peptides can be especially difficult to identify because incorporation of stable isotope tags into the cross-link, a strategy frequently used with longer cross-linking reagents, is not feasible.

In this study, we probed the solution structure of recombinant PRDX6 using chemical cross-linking combined with mass spectrometry (CX-MS). A substantial number of high-confidence zero-length cross-links clearly indicated differences between the solution structure of the enzyme in its reduced state and the previously reported crystal structure of the catalytic intermediate. The distance constraints defined by these cross-links were used in homology modeling experiments using the MODELLER program [25] to determine the solution structure of the reduced form of PRDX6. Comparison of the solution structure of the reduced form of PRDX6 determined using CX-MS and the crystal structure of the catalytic intermediate provides insights into conformational changes associated with the catalytic activity of this 1-Cys peroxiredoxin.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Expression and Purification of human PRDX6

A plasmid expressing human Prdx6 that had been codon optimized for E coli was purchased from DNA 2.0 (Menlo Park, CA). The codon optimized sequence of human Prdx6 was inserted into the plasmid pJExpress414 between an NdeI site and an XhoI site. The protein was then expressed as described previously [8, 10]. and purified using ion-exchange chromatography, resulting in a homogeneous product as determined by SDS-PAGE [6, 8, 10],

Sedimentation Equilibrium

The oligomeric state of human PRDX6 was determined using sedimentation equilibrium in an Optima XLI analytical ultracentrifuge. Immediately before the sedimentation experiment, samples were gel filtered in 20 mM Tris, 130 mM sodium chloride, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol pH 7.4 using 2 Superdex75 (GE Healthcare) columns connected in series and maintained at 4°C to remove any aggregates. For each experiment, a minimum of three different initial sample concentrations and two rotor speeds were analyzed. In some cases samples were analyzed at both 4°C and 30°C. Sample volumes of 110 μl were loaded into Epon double sector centerpieces. A water blank scan was acquired immediately prior to sample analysis and was used to correct for window distortion in the fringe displacement data [26]. Fringe displacement data were collected every 4 hours until equilibrium was obtained as determined from comparison of successive scans using the WinMatch v 0.99 program. The blank scan correction was edited using the WinReed v0.999 program. Global data analysis was performed using the WinNonlin v0.99 program. The programs WinMatch, WinReed and WinNonlin are available from the www.rasmb.org website.

Cross-linking Reactions

Cross-linking reactions were performed using previously described methods [20, 22]. Briefly, zero-length cross-linking reactions involving EDC and sulfo-NHS were performed at 0°C and 37°C, with final reagent concentrations of 20 mM and 10 mM, respectively, at 0°C and 2.5 mM and 1.25 mM, respectively, at 37°C. Aliquots of each reaction were removed and quenched at 15, 30, and 60 minutes for reactions performed at 0°C, and 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes for reactions performed at 37°C. Reactions involving disuccinimidyl glutarate (DSG) and disuccinimidyl suberate (DSS) were performed with a 1:1 ratio of deuterium vs. hydrogen-labeled cross-linkers, specifically DSG-D6/H6 and DSS-D12/H12, and final reagent concentrations of 0.125 mM for reactions at 37°C and 1 mM for reactions at 0°C. Aliquots of each reaction were quenched at 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes.

SDS-PAGE and Trypsin Digestion

The SDS-PAGE and trypsin digestion methods have been previously described [21]. Briefly, samples for the reactions described above were run in SDS-PAGE gels and bands of interest were excised and digested with trypsin.

MS Analysis and Identification of Cross-linked Peptides

For identification of zero-length cross-links, the cross-linked and control human PRDX6 tryptic digests were analyzed and cross-linked sites were identified as previously described using an LTQ-Orbitrap XL™ mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) [22]. Briefly, cross-linked and control samples were analyzed in parallel using LC-MS/MS and a label-free comparison was used to identify ions specific to the cross-linked samples. Data analysis and cross-linked peptide identification was performed using the ZXMiner program [22]. Cross-links for DSG and DSS were analyzed in a similar fashion using xQuest/xProphet [27].

Homology Modeling

The PRDX6 protein sequence and the 1PRX crystal structure were submitted to MODELLER 9v11 [25] to generate and refine human PRDX6 solution structures. All modeling experiments were run as 50-model trials using the “very slow” refinement algorithm and discrete optimized protein energy (DOPE) score as an output. Homology modeling and refinement were performed simultaneously by including known intra- and inter-subunit cross-links as distance restraints between α-carbons imposed at 11.0 +/− 0.1 Å. Each model was subject to 1,000 iterations and 10 optimization repeats. The completed models were then analyzed according to their DOPE score, and the highest-scoring model under this criterion was chosen for further analysis. Molecular graphics were illustrated using Open-Source PyMOL Version 1.3 [28], which also was used to calculate distances between α-carbons of cross-linked glutamate, aspartate, and lysine. No cross-links were observed involving the N-terminal amine group.

RESULTS

Human PRDX6 is in the reduced state

The recombinant human PRDX6 used in this study was shown to be in the reduced state by MS analysis. That is, neither Cys-47 nor C-91 were significantly oxidized to the sulfenic or higher oxidation states when the reported purification method [13] was used. Oxidation state was assessed by two independent methods. First, LC-MS/MS was used to analyze tryptic digests of representative purified preparations of the protein. Data were analyzed by considering all possible oxidation states of Cys in the database search and all identified forms of Cys-containing peptides were quantitated by integrating peak areas after extracting ion chromatographs for pertinent precursor ions. Potential oxidation was also assessed by analyzing the intact protein by ESI-MS analysis. In all cases, oxidation of the cysteines to sulfenic acid or higher oxidation states was less than 5%, unless the samples were deliberately oxidized or were stored for extended periods of time in solution at 0–4°C.

Human PRDX6 is a high affinity homodimer

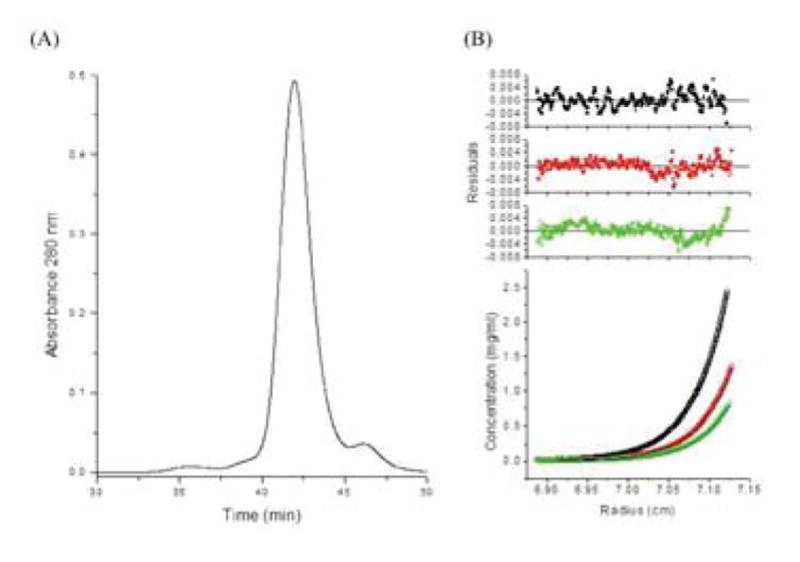

Separation of human PRDX6 by HPLC gel filtration showed a single prominent peak with an apparent mass of 45 kDa based upon comparison to a standard curve using globular proteins (Fig. 1A). This Stokes’ radius is within reasonable error of the molecular weight expected of a dimeric PRDX6 protein. The oligomeric state of the recombinant PRDX6 was evaluated by sedimentation equilibrium. These experiments were conducted by parallel analysis of three protein concentrations (0.2 mg/ml, 0.4 mg/ml, and 0.8 mg/ml). After equilibrium was reached, the resulting protein concentration curves were globally fit to various oligomeric models. As shown in Fig. 1B, the data best fit a dimeric model with no evidence of significant monomer, indicating that PRDX6 forms high affinity homodimers in solution with a Kd <20 nM.

FIGURE 1.

Oligomer states and conformations of human PRDX6 protein preparations. (A) HPLC gel filtration of recombinant human PRDX6. (B) Sedimentation equilibrium of the human PRDX6 peak at three different initial loading concentrations (0.8 mg/ml in black, 0.4 mg/ml in red, and 0.2 mg/ml in green) at 26,200 rpm and 30°C. All samples were prepared and analyzed in 20 mM Tris, 130 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol pH 7.4.

Zero-length CX-MS indicates that the solution structure diverges significantly from the crystal structure

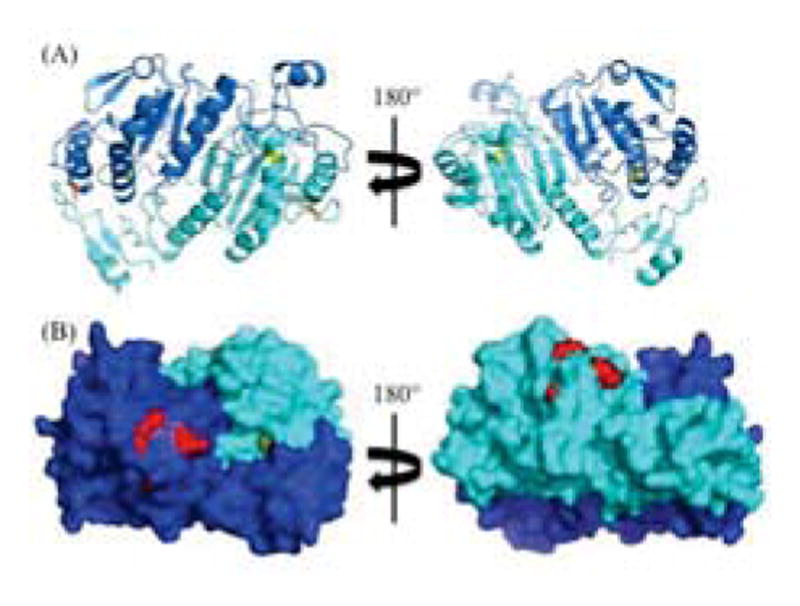

Fig. 2 shows the locations of the peroxidase and PLA2 active sites in the crystal structure of human PRDX6, which as noted above was prepared using a protein preparation where Cys 91 was mutated to a Ser and Cys-47 was oxidized to a sulfenic acid (PDB ID: 1PRX) [15]. In this structure of the peroxidase catalytic intermediate, the active site residues for PLA2 activity are on the surface, and the oxidized Cys-47 residue is solvent-accessible at the bottom of a deep hydrophobic cavity. However, Thr177, which can be phosphorylated and modulates PLA2 activity [12], is not solvent exposed in this structure. Chemical cross-linking was used to determine whether the solution structure of the reduced form of PRDX6 matched the crystal structure. Zero-length cross-linking was chosen for initial studies because these most precise distance constraints are the most valuable for evaluating and refining protein structures [16].

FIGURE 2.

Crystal structure of human PRDX6 (PDB ID: 1PRX). Subunit A in blue; Subunit B in cyan. (A) Cartoon representation of the dimer. Cys-47 in yellow sticks; Cys-91 in orange sticks. (B) Solid surface representation of the dimer. Phospholipase catalytic triad (Ser-26, His-32, Asp-140) in red spheres; Cys-47 in yellow spheres.

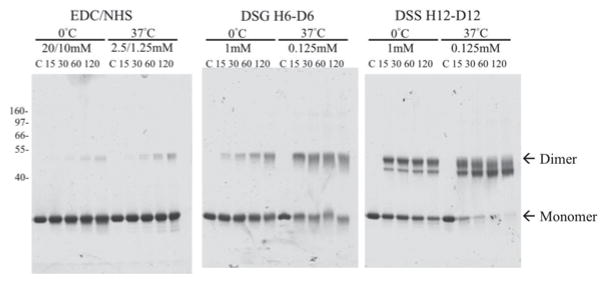

The protein was cross-linked at either 0°C or 37°C and reagent concentrations were adjusted to roughly compensate for the increased reaction rate of the higher temperature. Aliquots from each reaction were quenched over a range of time points to monitor for potential conformational distortion that could result from over-cross-linking (Fig. 3). Moderate yields of cross-linked dimers were observed at longer reaction times, consistent with a high affinity homodimer oligomeric state, as indicated by sedimentation equilibrium. No higher-order oligomers were detected. In addition, cross-linking of standard proteins confirmed that incidental cross-linking of molecules due to random collisions of non-associated molecules was not detectable with the conditions use here. For MS analysis, larger protein loads and multiple lanes of each reaction condition were separated on gels and the monomer and dimer bands across all EDC/NHS reaction time points were excised and digested with trypsin.

FIGURE 3.

Chemical cross-linking of the codon optimized human PRDX6. SDS-PAGE of the human PRDX6 after incubation with the indicated chemical cross-linkers. Control (C) and time points (minutes) are indicated above each lane. The position of molecular weight markers are shown on the left, and the migration of monomer and dimer bands are indicated.

Discovery MS analyses were performed by parallel LC-MS/MS analysis of the control sample (uncross-linked) and all timepoints of cross-linked monomer and dimer bands. The LC-MS patterns for the control and cross-linked sample were compared in a label-free mode to identify MS precursor ions unique to the cross-linked sample that were putative cross-linked peptides. Targeted LC-MS/MS was then conducted on the longest timepoint using a list of m/z and retention times for the putative cross-linked precursors. The longest timepoint was used because it was expected to have the highest yield of most cross-linked peptides. This targeted LC-MS/MS reanalysis was used to obtain high resolution, high mass accuracy spectra for both MS1 and MS2.

As part of the cross-link identification process, the final output obtained from the ZXMiner program [22] was examined, and only positively identified cross-links with a quality score (geometric mean or GM) higher than that of the highest-scoring false positive cross-link were considered as high confidence cross-links. Only high confidence cross-links were used in order to ensure that the dataset had a false discovery rate (FDR) of 0%. Finally, any ambiguities between multiple possible cross-linkable sites on identified cross-linked peptide complexes were evaluated using ZXMiner.

PyMOL was used to visualize zero-length cross-links on the crystal structure and determine distances between cross-linked residues. EDC cross-links are formed between amine and carboxyl groups that are within salt bridge distance [24], and these groups are primarily lysine and aspartate or glutamate side chains. However, α-carbon distances are typically used to evaluate cross-links because locations of protein backbones are better defined and less variable than side chains in either crystal structures, predicted models, or actual structures in solution. Considering side chain lengths and uncertainty of structures, most zero-length cross-links involve residues with α-carbons within 12Å. However, we previously showed that a few cross-links in well-characterized proteins have α-carbon distances up to about 16Å, particularly for cross-links involving coil regions or subunit-subunit linkages [22]. As such, we considered 12Å as the typical α-carbon limit for cross-linked residue distances with an upper limit of 16Å.

High confidence cross-links were assigned as intra-subunit, inter-subunit or ambiguous using several criteria. Cross-links confidently identified in the monomer band were considered to be intra-subunit. Cross-links observed in the dimer band were considered as either intra-subunit or inter-subunit and both distances were calculated. A difference between these two distances of more than 11Å resulted in assignment to the shorter distance possibility. Finally, for all ambiguous assignments, the crystal structure was visually examined using PyMOL for the presence of any major intervening structural elements, such as critical dimer interface contacts or an intervening helix. Using these criteria, at least 12 of 15 high confidence zero-length cross-links could be assigned as either intra-subunit or inter-subunit. Surprisingly, 8 of these 12 observed distances were substantially larger than the expected 12Å or 16Å limits (Table 1). This indicated that the solution structure of the reduced form of the enzyme deviated substantially from the crystal structure.

Table 1.

Human PRDX6 cross-links identified using EDC.

| Cross-link Group | z* | MH+ (Da)† | Mass Error (ppm) | Sequence-A‡ | Sequence-B‡ | Distance (Å)§ | Crosslinked Residues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter-Chain Cross-links | |||||||

| E01 | 4 | 1656.93474 | 4.6 | AA[K]LAPEFAK | [E]LPSGK | 19.8 | 56-210 |

| E02 | 3 | 2640.42255 | 4.1 | [E]LAILLGM#LDPAEKDEK | ELPSG[K]K | 27.5 | 109-215 |

| E03 | 3 | 2726.30843 | 5.7 | DINAYNC(EE)PTEK | GVFT[K]ELPSGK | 15.8 | 92/93-209 |

| E04 | 5 | 3040.64670 | 5.3 | LIALSIDSV[E]DHLAWSK | GVFT[K]ELPSGK | 22.4 | 77-209 |

| E05 | 4, 5 | 3044.62645 | 2.9 | [E]LAILLGM#LDPAEKDEK | GVFT[K]ELPSGK | 33.0 | 109-209 |

| E06 | 4 | 3238.80547 | 4.2 | ELAILLGM#LDPAEK[D]EK | VVISLQLTAE[K]R | 28.4 | 123-173 |

| E07 | 3, 4 | 3727.85644 | 1.8 | ELAILLGM#LDPAE[K]DEK | (D)G(D)SVM#VLPTIPEEEAK | 37.9 | 122-183/185 |

| Intra-Chain Cross-links | |||||||

| E08 | 3 | 1243.74389 | 6.2 | [K]LFPK | [E]LPSGK | 21.0 | 200-210 |

| E09 | 3 | 1748.92572 | 5.0 | GVFT[K]ELPSGK | YTPQ[P] | 18.9 | 209-224 |

| E10 | 4 | 1750.99291 | 4.9 | [K]LFPKGVFTK | YTPQ[P] | 12.6 | 200-224 |

| E11 | 3 | 1943.10067 | 4.8 | VVISLQLTAE[K]R | YTPQ[P] | 7.0 | 173-224 |

| E12 | 3, 4 | 2609.26208 | 4.5 | AA[K]LAPEFAK | DINAYNC(EE)PTEK | 10.3 | 56-92/93 |

| Ambiguous Cross-links|| | |||||||

| E13 | 3 | 2514.39782 | 5.5 | [E]LAILLGM#LDPAEKDEK | [K]LFPK | 49.9 | 40.0 | 109-200 |

| E14 | 5 | 2770.40894 | 1.3 | FHDFLG[D]SWGILFSHPR | ELPSG[K]K | 39.3 | 38.9 | 31-215 |

| E15 | 4 | 2872.47512 | 5.2 | AA[K]LAPEFAK | (D)G(D)SVMVLPTIPEEEAK | 20.3 | 26.3 | 56-183/185 |

Observed charge states of the cross-linked peptide.

Observed monoisotopic mass of observed peptide.

[]: cross-linked residue; (): potential cross-linked residue (ambiguous location); #: methionine oxidation.

All distances are between alpha-carbons of cross-linked residues in the human PRDX6 crystal structure (PDB ID: 1PRX).

Ambiguous cross-links are cross-links that could not be definitively assigned as inter- or intra-molecular; both distances are described in the table entry, separated by a slash. The inter-chain distance is before the slash, and the intra-chain distance is after the slash.

Determination of a solution structure for human PRDX6

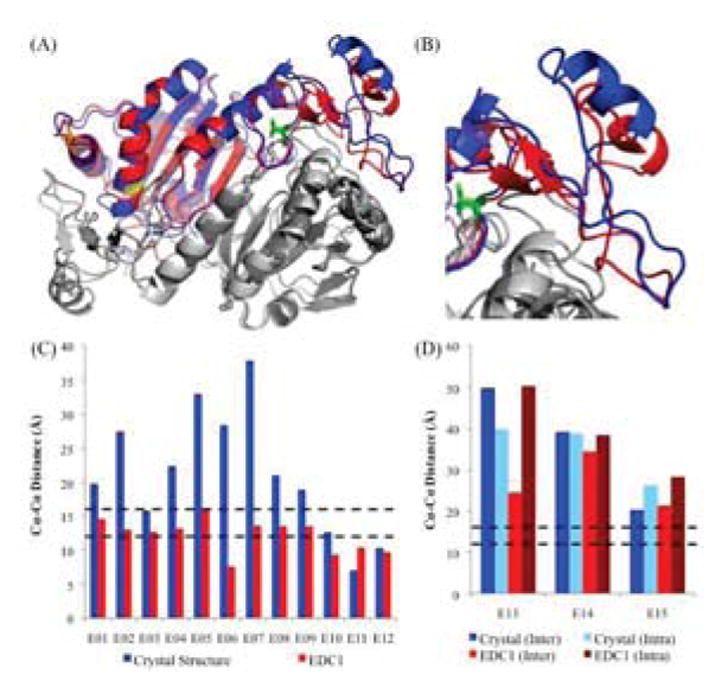

MODELLER was used to refine the 1PRX crystal structure by imposing α-carbon distance constraints for the 12 unambiguously assigned cross-links. The resulting preliminary model, hereafter referred to as the EDC1 model, was then compared to the crystal structure via a superposition (Fig. 4A), which showed that most major structural features in the PRDX6 homodimer remained unchanged, with an overall RMSD of 1.4 Å. Moreover, an analysis of the Ramachandran angles using Coot [29] for this model also revealed that over 90% were found in preferred or allowed conformations, reinforcing the validity of the model. The top 5 models generated, as ranked by discrete orbital proximal energy (DOPE) score, were also very similar to one another, indicating convergence on a best model.

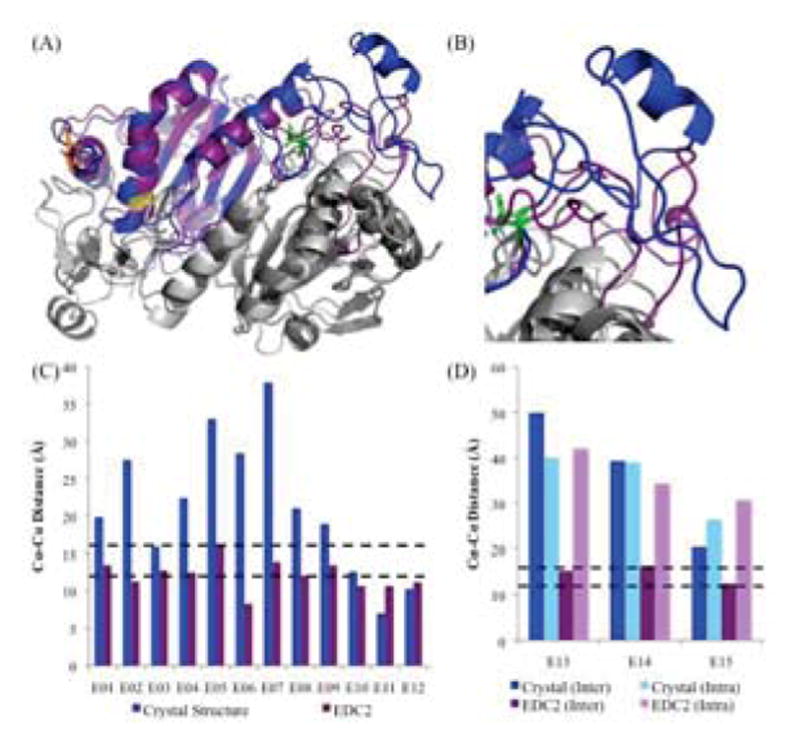

FIGURE 4.

Initial Molecular Model of human PRDX6 using EDC Cross-links. (A) Superposition of the crystal structure (blue) and EDC1 model (red) (RMSD: 1.4Å). For simplicity, only the A chain on both dimers is highlighted; both B chains are in gray. Cys-47 is shown in yellow sticks, Cys-91 is shown in orange sticks, and Thr-177 is shown in light green sticks. (B) Close-up of the C-terminal region on chain A, which shows the largest difference relative to the crystal structure (residues 190–224). (C) α-carbon distances between residues identified using EDC cross-links for the crystal structure and EDC1 model. Expected distance cutoffs are 12Å for well-ordered regions (lower black dashed line), and 16Å for disordered regions (upper black dashed line). (D) α-carbon distances between residues with ambiguous assignments as to whether they are inter-chain or intra-chain.

This model also pinpointed the area of maximum variability between the two structures as involving residues 190–224 (Fig. 4B), with an RMSD of 2.1 Å. The distances for the cross-links used as distance restraints were all below the 16Å cutoff point (Fig. 4C). In addition, the α-carbon distances for the three ambiguous cross-links that were not used in this structural refinement showed smaller inter-chain distances compared with the intra-chain distances in the EDC1 model (Fig. 4D). This trend coupled with the observation that all three cross-links had impeding intervening structures between their side chains for a putative intra-chain cross-link enabled us to assign them as inter-chain cross-links. However, they remained larger than the expected 16Å cutoff, indicating further refinement was needed.

A second model, hereafter referred to as the EDC2 model, was produced using MODELLER to refine the 1PRX crystal structure by imposing expected α-carbon distance constraints for all 15 EDC cross-links. Similar to the EDC1 model, most major structural features in the PRDX6 homodimer remained unchanged relative to the crystal structure with an overall RMSD of 1.7 Å (Fig. 5A) and the area of maximum variability between the two structures was residues 190–224 with an RMSD of 2.9 Å (Fig. 5B). This model was also analyzed via Ramachandran plot and found to have over 90% of its bond angles in allowed or preferred conformations. As before, the top 5 models by DOPE score were also structurally convergent. In this model, all 15 EDC cross-links were now within the 16Å maximum distance (Fig. 5C, 5D) indicating that all zero-length cross-link data supported this structure.

FIGURE 5.

Molecular Model of human PRDX6 using all EDC Cross-links. (A) Superposition of the crystal structure (blue) and EDC2 model (purple) (RMSD: 1.7Å). For details on color schemes and highlighted residues, see Fig. 4. (B) Close-up of the C-terminal region on chain A, which shows the largest difference relative to the crystal structure (residues 190–224). (C) α-carbon distances between residues identified using EDC cross-links for the crystal structure and EDC2 model. Expected distance cutoffs are 12Å for well-ordered regions (lower black dashed line), and 16Å for disordered regions (upper black dashed line). (D) α-carbon distances between residues with initially ambiguous assignments as to whether they are inter-chain or intra-chain.

Independent evaluation of the PRDX6 solution structure using homo-bifunctional cross-linkers

We performed independent CX-MS experiments on human PRDX6 using the homo-bifunctional cross-linkers DSG (H6/D6 mixture; 7.7 Å linker) and DSS (H12/D12 mixture; 11.4 Å linker) to further evaluate the PRDX6 solution structure (Fig. 3). As with the EDC experiments, the monomer and cross-linked dimer bands were excised, digested with trypsin, and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. These cross-linked peptides were identified using xQuest/xProphet [27]. The resulting high confidence cross-links (Tables 2 and 3) were mapped onto both the crystal structure and the EDC2 structure (Fig. 6A, 6B). Due to the lengths of the spacer arms between the reactive groups of these cross-linkers [24], maximum α-carbon distances of 22Å for DSG and 26Å for DSS were used, consistent with previous studies using these cross-linkers [21]. When the crystal structure was analyzed, 4 of 10 DSG cross-links exceeded the maximum expected distance threshold, further confirming that the solution structure of the reduced protein significantly differed from that of the catalytic intermediate. However, 3 of these 4 cross-links were within expected limits when the EDC2 model was considered. For DSS, which has an even longer spacer arm, none of the cross-links exceeded the threshold for that cross-linker on any of the structures, indicating the inability of this longer cross-link to distinguish between alternative conformations. The single DSG cross-link (D10) that continued to exceed the expected distance threshold in the EDC2 structure was further evaluated. Interestingly, this cross-link involved Lys204, which is located within the most variable region of the protein as described above. This cross-link (Table 2) was also notable because its assignment as an inter-chain or intra-chain cross-link was ambiguous when compared to the 1PRX crystal structure due to α-carbon distances of 30.3Å and 36.3Å for inter-chain and intra-chain interactions, respectively. There also were intervening structural elements for both possible types of cross-link. However, this controversy was resolved when the EDC2 model was examined, as the inter-chain interaction no longer had major intervening structural elements and displayed an α-carbon distance of 26.1Å, as opposed to 42.5Å for the intra-chain interaction.

Table 2.

Human PRDX6 cross-links identified using DSG.

| Cross-link Group | z* | MH+ (Da)† | Mass Error (ppm) | Sequence-A‡ | Sequence-B‡ | Cross-linked Residues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter-Chain Cross-links | ||||||

| D01 | 4 | 1898.042 | −4.8 | AA[K]LAPEFAK | ELPSG[K]K | 56-215 |

| D02§ | 4 | 1955.988 | −5.2 | DE[K]GMPVTAR | ELPSG[K]K | 125-215 |

| D03 | 4 | 2302.258 | 0.5 | GVFT[K]ELPSGK | AA[K]LAPEFAK | 209-56 |

| D04 | 4 | 2376.195 | −1.9 | GVFT[K]ELPSGK | DE[K]GM#PVTAR | 209-125 |

| D05 | 4 | 2570.369 | −1.5 | VVISLQLTAE[K]R | DE[K]GM#PVTAR | 173-125 |

| Intra-Chain Cross-links | ||||||

| D06 | 4 | 2630.409 | −0.1 | L[K]LSILYPATTGR | DE[K]GMPVTAR | 144-125 |

| D07 | 4 | 2826.431 | 3.8 | DGDSVM#VLPTIPEEEA[K]K | ELPSG[K]K | 199-215 |

| D08 | 3 | 2883.675 | −1.5 | L[K]LSILYPATTGR | VVISLQLTAE[K]R | 144-173 |

| D09 | 5 | 3263.753 | −0.6 | NV[K]LIALSIDSVEDHLAWSK | LAPEFA[K]R | 67-63 |

| Ambiguous Cross-links | ||||||

| D10 | 4 | 2176.226 | −1.4 | AA[K]LAPEFAK | LFP[K]GVFTK | 56-204 |

Observed charge states of the cross-linked peptide.

Observed monoisotopic mass of observed peptide.

[]: cross-linked residue; (): potential cross-linked residue (ambiguous location); #: methionine oxidation.

Multiple variants of this cross-link have been identified in this dataset.

Table 3.

Human PRDX6 cross-links identified using DSS.

| Cross-link Group | z* | MH+ (Da)† | Mass Error (ppm) | Sequence-A‡ | Sequence-B‡ | Cross-linked Residues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter-Chain Cross-links | ||||||

| S01§ | 4 | 1940.09 | −4.2 | AA[K]LAPEFAK | ELPSG[K]K | 56-215 |

| S02§ | 4 | 1998.038 | −3.7 | DE[K]GMPVTAR | ELPSG[K]K | 125-215 |

| S03§ | 4 | 2344.296 | −3.6 | GVFT[K]ELPSGK | AA[K]LAPEFAK | 209-56 |

| S04§ | 4 | 3469.896 | −0.8 | ELAILLGM#LDPAE[K]DEK | L[K]LSILYPATTGR | 122-144 |

| S05 | 5 | 3523.839 | −3.7 | ELAILLGM#LDPAE[K]DEKGM#PVTAR | ELPSG[K]K | 122-215 |

| Intra-Chain Cross-links | ||||||

| S06§ | 4 | 2688.448 | −1.6 | L[K]LSILYPATTGR | DE[K]GM#PVTAR | 144-125 |

| S07 | 4 | 2925.727 | 0 | L[K]LSILYPATTGR | VVISLQLTAE[K]R | 144-173 |

| S08 | 4 | 3830.905 | −0.8 | DINAYNCEEPTE[K]LPFPIIDDR | AA[K]LAPEFAK | 97-56 |

Observed charge states of the cross-linked peptide.

Observed monoisotopic mass of observed peptide.

[]: cross-linked residue; (): potential cross-linked residue (ambiguous location); #: methionine oxidation.

Multiple variants of this cross-link have been identified in this dataset.

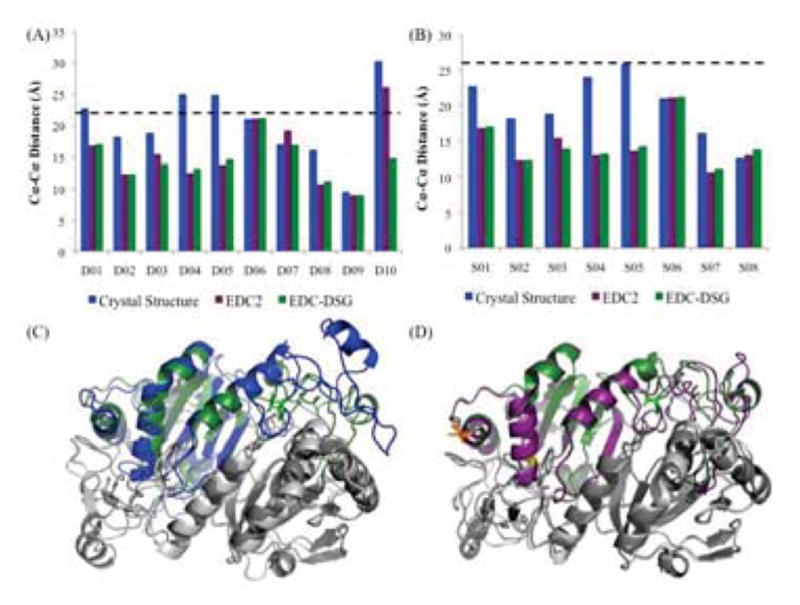

FIGURE 6.

Evaluation of Solution Structure Using Non-Zero-Length Cross-linkers. (A) Histogram analysis of α-carbon distances between residues identified using DSG cross-links for the crystal structure (blue), EDC2 model (purple), and Final model (forest green). Expected distance cutoff is 22Å (dashed black line). (B) Histogram analysis of α-carbon distances between residues identified using DSS cross-links for the crystal structure, EDC2 model, and Final model. Expected distance cutoff is 26Å. (C) Superimposition of the crystal structure (blue) and Final model (forest green) (RMSD: 1.6Å). For details on color schemes and highlighted residues, see Fig. 4. (D) Superimposition of the EDC2 model (purple) and Final model (forest green) (RMSD: 0.7Å).

In order to further explore the impact of the D10 DSG cross-link on the protein structure, we generated a final solution structure using MODELLER to refine the 1PRX crystal structure by imposing expected α-carbon distance constraints for all 15 EDC cross-links plus the D10 distance constraint. All DSG and DSS cross-links were within expected limits in this model (Fig. 6A, 6B). We then compared the final structure to the crystal structure (Fig. 6C). As with the above models, overall backbone structure was similar with an RMSD of 1.6 Å and the RMSD of the C-terminal tail (residues 190–224) was 2.4 Å, which indicated that this region was actually slightly closer to the crystal structure than in the EDC2 model. This model was also analyzed via Ramachandran plot, and once again we found that over 90% of its bond angles were in preferred or allowed regions. The top 5 models by DOPE score also converged structurally. The final model was also directly compared to the EDC2 model (Fig. 6D). As expected, the differences between the EDC2 model and the final solution structure were minor with an overall RMSD of 0.74Å and an RMSD of 1.0 for the C-terminal region. Their distributions of Ramachandran bond angles were quite similar overall.

DISCUSSION

We utilized CX-MS and structural refinement with cross-link distance constraints to determine an experimentally validated solution structure of the reduced form of PRDX6. The final structure fits distance constraints of all high confidence cross-links using reagents with three different cross-link spacer arms (0, 7.7 and 11.4 Å). Consistent with prior studies, the zero-length cross-links were the most useful for identifying conformational differences between the solution structure of the reduced protein and the crystal structure of the catalytic intermediate. In contrast, the longest cross-linker was too imprecise and could not unambiguously identify any discrepancies between the solution structure and the crystal structure. The differences between the solution structure and crystal structure were mostly, but not entirely, located within the C-terminal tail of the protein (residues 190–224). This region is primarily comprised of coil, which probably contributes to its plasticity. However, the fact that all 33 distance constraints can be satisfied by a single structure suggests, but does not prove, that the solution structure of the protein as isolated herein is primarily a single conformation rather than an ensemble of inter-converting structures.

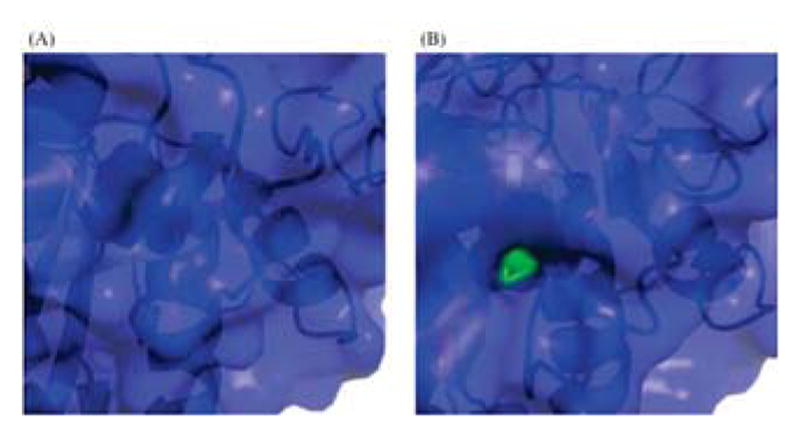

Importantly, significant changes in protein structure are not limited to residues 190–224. Another functionally important change is the solvent accessibility of Thr-177. As noted above, this residue is phosphorylated in response to certain stimuli and increases PLA2 activity and affinity for liposomes [12], but it is completely buried in the crystal structure. In contrast, this residue is substantially solvent exposed in our EDC2 model and the final solution structure (Fig. 7). Taken together, these data suggest that the reduced form, but not the oxidized form of the enzyme, should be capable of being phosphorylated.

FIGURE 7.

Surface Accessibility of Thr-177 in PRDX6 Crystal and Solution Structures. Closeup of protein surface display for Thr-177 (green spheres) in (A) 1PRX crystal structure, and (B) EDC2 solution structure.

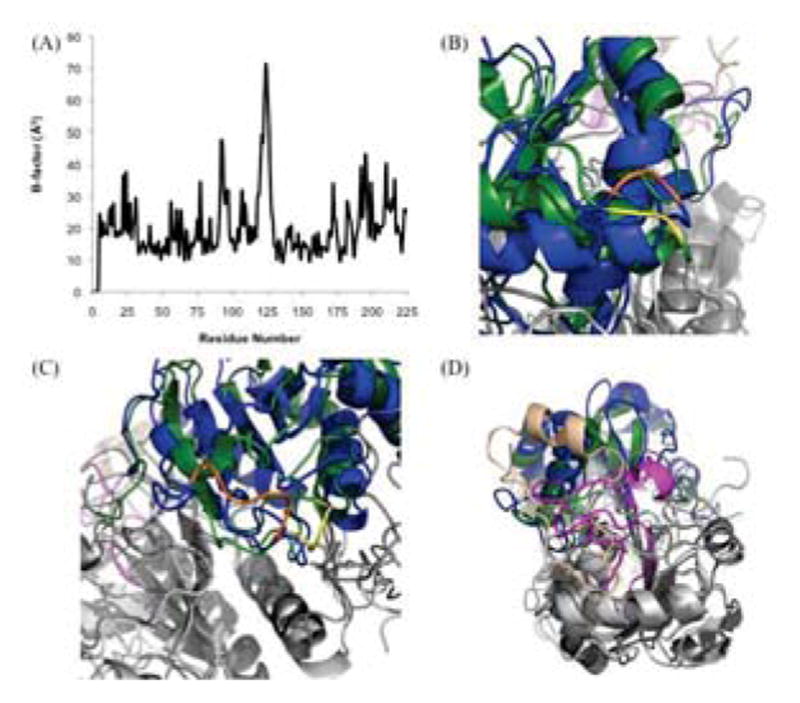

We also evaluated whether the conformational differences between the solution and crystal structures correlated with the most flexible regions in the crystal structure. An analysis of the Debye-Waller temperature factors (B-factors) in the crystal structure (Fig. 8A), shows that residues 92–93 and 121–126 exhibited the highest B-factors. The remainder of the protein had B-factors less than 40, which are indicative of relatively rigid structures. Comparison of residues 92–93 in the crystal structure and the final solution structure show that this coil region is not any more variable than its flanking regions (Fig. 8B). Residues 121–126 encompass another coil region that also does not exhibit substantially greater variability between structures than other adjacent coil regions. Interestingly, however, this region is significantly more compact in the final solution model compared with the crystal structure (Fig. 8C). Finally, as noted above, the C-terminal region encompassed by residues 190–224 shows the largest variation between the two structures (Fig. 8D) but this region does not have high B-factors. Interestingly, an analogous region in 2-Cys peroxiredoxins also exhibits conformational change as part of the catalysis process [4]. However, there is one key difference in that the 2-Cys C-terminal region experiences localized unfolding in response to the breaking of a disulfide bond, whereas the analogous region in PRDX6 becomes more compact. Overall, there does not appear to be a strong correlation between regions of high flexibility in the crystal structure and regions involved in conformational changes associated with transition from the reduced form to the peroxidase catalytic intermediate form of the enzyme. This suggests that these conformational changes play an important role in the catalytic mechanism and do not simply reflect variations in intrinsically mobile regions of the protein. It also suggests that these conformational changes associated with the peroxidase mechanism could help regulate PLA2 activity. That is, when the enzyme is in the reduced form, but not the catalytic intermediate state, Thr-177 is solvent exposed and can be phosphorylated thereby increasing PLA2 activity and affinity for liposomes.

FIGURE 8.

Relationship of B-factors and Variations Between the PRDX6 Crystal and Solution Structures. (A) Analysis of B-factors for 1PRX crystal structure. (B) Superposition of 1PRX crystal structure (blue) and Final model (forest green) highlighting residues Glu-92 and Glu-93 (orange and yellow for 1PRX and Final, respectively). (C) Superposition of 1PRX crystal structure (blue) and Final model (forest green) highlighting residues Glu-92 and Glu-93 (orange and yellow for 1PRX and Final, respectively). (D) Superposition of 1PRX crystal structure (blue) and Final model (forest green) highlighting residues 190–224 (wheat and magenta for 1PRX and Final, respectively).

This study highlights the advantages of using zero-length cross-linkers for probing fairly subtle but biologically important conformational changes. Zero-length cross-links have been previously shown to be the most useful type of cross-link for refining protein structures and experimentally verifying homology models [16]. However, this approach has been under-utilized, due to the increased difficulty of identifying such cross-links. These difficulties are due to the fact that stable isotope tags or other features that aid in mass spectrometry-based identification of cross-linked peptides cannot be exploited with a cross-linker that does not incorporate external atoms into the cross-link bridge. This hurdle has recently been addressed by development of an analysis strategy using label-free LC-MS comparisons, targeted acquisition of high mass accuracy MS/MS spectra of putative cross-links, and development of the ZXMiner software that has been optimized for in-depth identification of zero-length cross-links [22]. The power of this approach for in-depth analysis was previously demonstrated by comparing alternative programs on the same dataset [21]. It is further demonstrated here by the identification of a greater number of high-confidence cross-links EDC (15 unique cross-link sites) when compared to DSG (10 cross-link sites) or DSS (8 cross-link sites). This larger number of zero-length cross-links was identified despite less extensive overall apparent cross-linking relative to the DSG and DSS reactions as indicated by the less extensive formation of covalently linked homodimers on SDS gels (Fig. 3). More importantly, EDC cross-linking represented the most sensitive test for conformational changes. When observed cross-links were compared to the crystal structure, 8 of 12 EDC cross-links (67%) involved residues that were further apart than the maximum likely distance, whereas only 4 of 10 DSG (40%) and 0 of 8 DSS (0%) cross-links were outside expected maximum distances.

In-depth identification of substoichiometric levels of cross-links is important for structural studies because extensive chemical modification of a protein may perturb its structure. To minimize the risk of this complication, cross-link reaction time courses were always analyzed (Fig. 3), and evidence of precursor ions corresponding to identified cross-linked complexes was required at the early timepoints as previously described [23]. Also, it is likely that zero-length cross-linking may be less sensitive to over-cross-linking and conformational perturbation because the reaction is reversible and dead end products are typically not formed. In contrast, amine-specific homo-bifunctional cross-linkers like DSG and DSS will readily modify most or all solvent-exposed surface amines, resulting in a large change of net surface charge. In addition, if the second site on the reagent does not react with another amine on the protein, a dead end product is formed. This irreversible reactivity of most exposed amines makes over-reaction and conformational perturbation a substantial concern for such cross-linkers.

In summary, the solution structure of the reduced form of PRDX6 is of particular interest because multiple biochemical studies have identified conformational changes of the protein that are associated with changes in enzyme activity and the only reported high resolution crystal structure is of the peroxidase catalytic intermediate form of the protein [15]. Our development of an experimentally supported solution structure is consistent with multiple biochemical studies that indicate PRDX6 is a protein with substantial plasticity that can affect both known enzyme activities of this protein. It also yields novel insights regarding the nature of the changes that occur during the peroxidase catalysis and the likely interplay between regulation of the two enzyme activities as indicated by the solvent accessibility of Thr-177. The reported structure also provides an important structural reference for this protein, as the reduced form of PRDX6 is much more commonly encountered than the peroxidase catalytic intermediate. These insights combine to give us a greater understanding of this important antioxidant enzyme.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the Wistar Institute Proteomics Core and the expert assistance of Peter Hembach and Elena Sorokina.

Footnotes

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health grants HL10216 (to A. B. F.), CA10815 (NCI core grant to the Wistar institute), and T32 GM008275 (to R. R. S.).

References

- 1.Fisher AB, Forman HJ, Glass M. Mechanisms of pulmonary oxygen toxicity. Lung. 1984;162:255–259. doi: 10.1007/BF02715655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lang JD, McArdle PJ, O’Reilly PJ, Matalon S. Oxidant-antioxidant balance in acute lung injury. Chest. 2002;122:314S–320S. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.6_suppl.314s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahman I, Adcock IM. Oxidative stress and redox regulation of lung inflammation in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:219–242. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00053805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wood ZA, Schroder E, Robin Harris J, Poole LB. Structure, mechanism and regulation of peroxiredoxins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:32–40. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhee SG, Chae HZ, Kim K. Peroxiredoxins: a historical overview and speculative preview of novel mechanisms and emerging concepts in cell signaling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:1543–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manevich Y, Fisher AB. Peroxiredoxin 6, a 1-Cys peroxiredoxin, functions in antioxidant defense and lung phospholipid metabolism. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:1422–1432. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang SW, Baines IC, Rhee SG. Characterization of a mammalian peroxiredoxin that contains one conserved cysteine. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6303–6311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manevich Y, Reddy KS, Shuvaeva T, Feinstein SI, Fisher AB. Structure and phospholipase function of peroxiredoxin 6: identification of the catalytic triad and its role in phospholipid substrate binding. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:2306–2318. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700299-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisher AB, Dodia C, Manevich Y, Chen JW, Feinstein SI. Phospholipid hydroperoxides are substrates for non-selenium glutathione peroxidase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21326–21334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.30.21326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen JW, Dodia C, Feinstein SI, Jain MK, Fisher AB. 1-Cys peroxiredoxin, a bifunctional enzyme with glutathione peroxidase and phospholipase A2 activities. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28421–28427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005073200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ralat LA, Manevich Y, Fisher AB, Colman RF. Direct evidence for the formation of a complex between 1-cysteine peroxiredoxin and glutathione S-transferase pi with activity changes in both enzymes. Biochemistry. 2006;45:360–372. doi: 10.1021/bi0520737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Y, Feinstein SI, Manevich Y, Chowdhury I, Pak JH, Kazi A, Dodia C, Speicher DW, Fisher AB. Mitogen-activated protein kinase-mediated phosphorylation of peroxiredoxin 6 regulates its phospholipase A(2) activity. Biochem J. 2009;419:669–679. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rahaman H, Zhou S, Dodia C, Feinstein SI, Huang S, Speicher D, Fisher AB. Increased phospholipase A2 activity with phosphorylation of peroxiredoxin 6 requires a conformational change in the protein. Biochemistry. 2012;51:5521–5530. doi: 10.1021/bi300380h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manevich Y, Shuvaeva T, Dodia C, Kazi A, Feinstein SI, Fisher AB. Binding of peroxiredoxin 6 to substrate determines differential phospholipid hydroperoxide peroxidase and phospholipase A(2) activities. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;485:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi HJ, Kang SW, Yang CH, Rhee SG, Ryu SE. Crystal structure of a novel human peroxidase enzyme at 2.0 A resolution. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:400–406. doi: 10.1038/nsb0598-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leitner A, Walzthoeni T, Kahraman A, Herzog F, Rinner O, Beck M, Aebersold R. Probing native protein structures by chemical cross-linking, mass spectrometry, and bioinformatics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:1634–1649. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R000001-MCP201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greber BJ, Boehringer D, Leibundgut M, Bieri P, Leitner A, Schmitz N, Aebersold R, Ban N. The complete structure of the large subunit of the mammalian mitochondrial ribosome. Nature. 2014;515:283–286. doi: 10.1038/nature13895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaake RM, Wang X, Burke A, Yu C, Kandur W, Yang Y, Novtisky EJ, Second T, Duan J, Kao A, Guan S, Vellucci D, Rychnovsky SD, Huang L. A new in vivo cross-linking mass spectrometry platform to define protein-protein interactions in living cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13:3533–3543. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.042630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olson AL, Tucker AT, Bobay BG, Soderblom EJ, Moseley MA, Thompson RJ, Cavanagh J. Structure and DNA-binding traits of the transition state regulator AbrB. Structure. 2014;22:1650–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li D, Harper SL, Tang HY, Maksimova Y, Gallagher PG, Speicher DW. A comprehensive model of the spectrin divalent tetramer binding region deduced using homology modeling and chemical cross-linking of a mini-spectrin. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:29535–29545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.145573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sriswasdi S, Harper SL, Tang HY, Gallagher PG, Speicher DW. Probing large conformational rearrangements in wild-type and mutant spectrin using structural mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:1801–1806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317620111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sriswasdi S, Harper SL, Tang HY, Speicher DW. Enhanced identification of zero-length chemical cross-links using label-free quantitation and high-resolution fragment ion spectra. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:898–914. doi: 10.1021/pr400953w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harper SL, Sriswasdi S, Tang HY, Gaetani M, Gallagher PG, Speicher DW. The common hereditary elliptocytosis-associated alpha-spectrin L260P mutation perturbs erythrocyte membranes by stabilizing spectrin in the closed dimer conformation. Blood. 2013;122:3045–3053. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-487702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paramelle D, Miralles G, Subra G, Martinez J. Chemical cross-linkers for protein structure studies by mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2013;13:438–456. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sali A, Blundell TL. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yphantis D. Equilibrium centrifugation of dilute solutions. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1964;3:297–317. doi: 10.1021/bi00891a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rinner O, Seebacher J, Walzthoeni T, Mueller LN, Beck M, Schmidt A, Mueller M, Aebersold R. Identification of cross-linked peptides from large sequence databases. Nat Methods. 2008;5:315–318. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schrödinger L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.5.0.4. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]