Abstract

Objective

Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders predominantly afflict women, suggesting that estrogen may play a role in the disease process. Defects in mechanical loading-induced TMJ remodeling are believed to be a major etiological factor in TMJ degenerative disease. Previously, we found that, decreased occlusal loading caused a significant decrease in early chondrocyte maturation markers (Sox9 and Col 2) in female, but not male, C57BL/6 wild type mice (1). The goal of this study was to examine the role of Estrogen Receptor (ER) beta in mediating these effects.

Design

21-day-old male (n=24) and female (n=25) ER beta KO mice were exposed to decreased occlusal loading (soft diet administration and incisor trimming) for 4 weeks. At 49 days of age the mice were sacrificed. Proliferation, gene expression, Col 2 immunohistochemistry and micro-CT analysis were performed on the mandibular condyles.

Results

Decreased occlusal loading triggered similar effects in male and female ER beta KO mice; specifically, significant decreases in Col 10 expression, subchondral total volume, bone volume, and trabecular number.

Conclusion

Decreased occlusal loading induced inhibition of chondrocyte maturation markers (Sox9 and Col 2) did not occur in female ER beta deficient mice.

Keywords: mouse, temporomandibular joint, estrogen receptor beta, mechanical loading

1. Introduction

Approximately 35 million people in the United States suffer from TMJ problems at any given time. Thirty to fifty percent of individuals diagnosed with a temporomandibular joint disorder have temporomandibular joint degenerative disease (TMJ-DD) (2). TMJ-DD predominantly afflicts women, with a mean age range of 44-55 years (3, 4). The cause of this sex predilection remains largely unknown. Current theory suggests that TMJ degeneration is the result of excessive altered joint loading surpassing the mechanical loading-induced remodeling capacity of the joint (5, 6).

We have developed a murine model of decreased occlusal loading TMJ remodeling, enabling us to study mechanical loading-induced TMJ remodeling. In this decreased occlusal loading model, the incisors are trimmed at regular intervals (1mm every other day) and the normal hard pellet diet is replaced with a soft-dough diet. We previously found that decreased occlusal loading consistently led to decreased subchondral bone volume and decreased mandibular condylar cartilage thickness (7). In addition, decreased occlusal loading was found to cause sex differences in chondrocyte maturation expression in the temporomandibular joints of C57BL/6 and CD-1 wild type (WT) mice. When compared with normal loading controls, 21-day-old female, but not male, WT mice exposed to 4 weeks of decreased occlusal loading exhibited significant decreases in Sox9 and Collagen type II expression (1). This gender-related disparity suggests that estrogen may play a role in TMJ mechanical loading-induced remodeling.

There are two classic estrogen receptors: alpha and beta. Male and female mice deficient in estrogen receptor alpha express a characteristic skeletal phenotype (8). In contrast, only female mice deficient in estrogen receptor beta display a unique skeletal phenotype (9, 10). It is believed that high estrogen levels are required to activate estrogen receptor beta; therefore, the skeletal phenotype is not expressed in male estrogen receptor beta knockout mice due to insufficient estrogen levels. Characterization of the TMJ from estrogen receptor beta deficient mice, compared with age- and sex-matched WT mice, revealed increased mandibular condylar cartilage thickness in female deficient (KO) mice, due to decreased cartilage turnover (11). The purpose of this study is to examine the role of estrogen receptor beta in mediating the effects of decreased occlusal loading induced TMJ remodeling. Our hypothesis is that ER beta deficiency in C57BL/6 WT mice will prevent sex differences in mandibular chondrocyte maturation that normally occur with decreased occlusal loading. In order to examine this effect, we evaluated male and female ER beta KO mice exposed to decreased occlusal loading.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Animals

ER beta KO mice (homozygous male, heterozygous female, Cat# 004745) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). For the experiments requiring ER beta KO mice, only homozygous females and males were used. 21-day-old male (n=24) and female ER beta KO mice (n=25) were used in this study.

2.2 Experimental Design

2.2.1 Loading model

At 21 days of age, male and female ER beta KO mice, in a C57BL/6 background, were each divided into two groups: (1) normal loading for 4 weeks, and (2) decreased occlusal loading for 4 weeks (Table 1). The decreased loading groups were fed a soft-dough diet (Transgenic Dough Diet, with the same nutritional composition as the normal-pellet diet; BioServ, Frenchtown, NJ) and their mandibular incisors were trimmed, using an orthodontic light wire clipper, by approximately 1 mm every other day for 4 weeks (the unimpeded eruption rate of mandibular incisors in mice is approximately 0.4 mm per day (12); incisor trimming maintains an anterior open bite of 0.5 to 1.0 mm). After 4 weeks of decreased loading (49 day old), the mice were sacrificed. Three hours prior to euthanasia, the mice were injected, intraperitoneally, with 0.1 mg bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) per gram body weight. The body weight was monitored twice per week. Mice lost more than 20% of body weight were eliminated from the experiment. All experiments were performed in accordance with animal welfare based on an approved IACUC protocol #AAAD0950 from the Columbia University animal care committee.

Table 1.

Number of mice.

| Sex | Total (n) | Treatment | Real Time PCR (n) | Histology/μCT (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 24 | Normal Loading | 6 | 6 |

| Decreased Occlusal Loading | 6 | 6 | ||

| Female | 25 | Normal Loading | 6 | 7 |

| Decreased Occlusal Loading | 6 | 6 |

μCT: micro-computed tomography; n=number of mice.

2.2.2 Histomorphometry

Whole mouse heads were sectioned into two halves, fixed in 10% formalin for 4 days at room temperature and decalcified in 14% EDTA (pH 7.1) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 10 days. Subsequently, the samples were processed through progressive concentrations of ethanol, cleared in xylene and embedded in paraffin. The TMJ was serially sectioned along the sagittal plane at 5-μm thickness, by Microm HM 355s microtome (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA); every fifth section was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Mandibular condylar cartilage thickness was measured in a blinded, nonbiased manner using the BioQuant computerized image analysis system (BioQuant, Nashville, TN, USA). Mandibular condylar cartilage thickness was performed on H&E sagittal sections corresponding to the mid-coronal portion of the mandibular condylar head. The mandibular condylar cartilage area was divided into two layers, non-hypertrophic (cells < 8 μm in height, includes superficial, polymorphic and flattened zones) and hypertrophic (cells >8 μm in height) (Figure 1A). The anterior-posterior region of the mandibular condylar cartilage was restricted to the region that contains multilayer hypertrophic chondrocytes. Three to five sections, corresponding to the same anatomical area (mid-sagittal), were analyzed for each animal and the average of these sections was used for the thickness of this mouse.

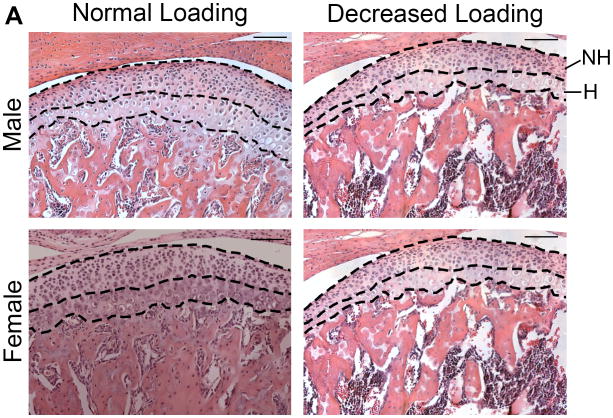

Figure 1.

A. H & E staining of sagittal sections of the TMJ from 49 days old male and female ER beta KO mice exposed to normal or decreased occlusal loading (incisor trimming and soft diet administration) for 4 weeks. The non-hypertrophic (NH) and hypertrophic (H) zones were delineated with black dashed lines. n=6-7 mice for each sex and treatment. Bars=100μm. (10× magnification) B. Thickness of total cartilage, non-hypertrophic zone and hypertrophic zone. Values are the means and SEM. * and ** significant difference between decreased occlusal loading and normal loading: * p<0.05, ** p<0.01.

2.2.3 Immunohistochemistry

Tissue sections were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated with decreasing concentrations of ethanol. Following rehydration, the sections were treated with 3% peroxide to block endogenous peroxidase activity and digested for 60 minutes with pepsin for unmasking (Lab Vision, Fremont, CA, USA; Cat# AP-9007-006). All sections were blocked with Protein Block Serum-Free (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA, USA; Code# X0909), and then incubated with Collagen type II primary antibody (Millipore; MAB8887, 1:200 dilution) at room temperature for 30 minutes. Immunohistochemical staining was performed using the LSAB + System-HRP Kit (DakoCytomation; Code# K0690) according to the procedure recommended by the manufacturer.

BrdU immunohistochemical analysis was completed using a BrdU staining kit as per the manufacturer's instructions (Zymed Laboratories-Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Negative controls were prepared by omitting the primary antibody step and incubating with blocking solution. BrdU was quantified by calculating the labeling index (number of BrdU positive cells divided by the total number of cells). Three to five sections, corresponding to the same anatomical area (mid-sagittal), were calculated for each animal and the average of these sections was used as the mean labeling index.

2.2.4 Gene expression

The mandibular condylar heads (left and right), containing both the mandibular condylar cartilage and subchondral bone, were carefully harvested from each mouse and all soft tissues were removed under a dissecting microscope. Total RNA was extracted, from each condylar head, using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) as per the manufacturer's protocol. Total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the ABI High Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) as per the manufacturer's protocol. For quantification of gene expression, real-time PCR was performed in separate wells (single-plex assay) of a 96-well plate with a reaction volume of 20 μL. Gapdh was used as an endogenous control. Three replicates of each sample were amplified using Assays-on-Demand Gene Expression (Applied Biosystems), with predesigned unlabeled gene-specific PCR primers and TaqMan MGB FAM dye-labeled probes, for the particular gene of interest. The PCR reaction mixture (including 2× TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix, 20× Assays-on-Demand Gene Expression Assay Mix, 50 ng of cDNA) was run in an Applied Biosystems ABI Prism 7300 Sequence Detection System instrument utilizing universal thermal cycling parameters. For the genes in which efficiencies of target and endogenous control amplification were approximately equal, relative expression in a test sample was compared with a reference calibrator sample (ΔΔCt method) and used for data analysis. For genes that were not amplified with the same efficiency as the endogenous control the Relative Standard Curve method, in which the target quantity is determined from the standard curve and divided by the target quantity of the calibrator, was used. Gene expression was performed for Parathyroid hormone-related protein (Pthrp), SRY-box containing gene 9 (Sox9), Collagen type II (Col2a1), Indian Hedgehog (Ihh), and Collagen type X (Col10a1).

2.2.5 Micro-CT analysis

The subchondral bones of the mandibular condyles from ERβ KO female mice were analyzed. The three-dimensional morphology of the subchondral bone was evaluated by the micro–computed tomography (μCT) facility at the University of Connecticut Health Center. Analysis included bone volume, total volume, trabecular number, trabecular spacing, and trabecular thickness.

2.3 Statistical analyses

Statistical significance of differences among means was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc comparison of more than two means by the Bonferroni method using GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

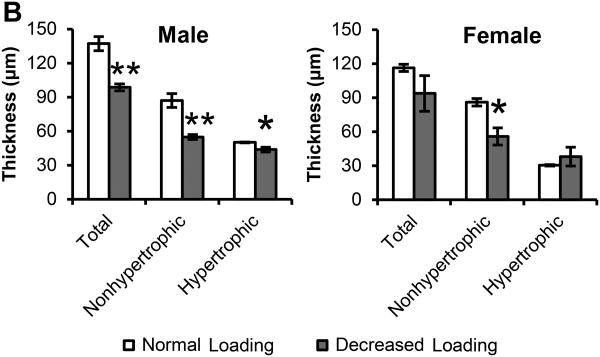

3.1 Cartilage thickness and Cell proliferation

In female ER beta KO mice, decreased occlusal loading caused a significant decrease in non-hypertrophic cartilage thickness (p<0.05). In male ER beta KO mice, decreased occlusal loading caused a significant decrease in total condylar cartilage thickness (p<0.01), non-hypertrophic cartilage thickness (p<0.01) and hypertrophic cartilage thickness (p<0.05) (Figure 1). BrdU labeling revealed that decreased occlusal loading did not cause any significant changes in proliferation in both male and female ER beta KO mice (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proliferation in 21-day old male and female ER beta KO mice exposed to normal, or decreased occlusal loading (incisor trimming and soft diet administration) for 4 weeks. For each mouse, 3-5 sections were analyzed. Mice were injected with BrdU 3 hr prior to euthanasia. The total number of BrdU labeled cells was divided by the total number of cells to calculate the ratio of BrdU label for each mouse. Values are the means and SEM for n=6-7 mice per group.

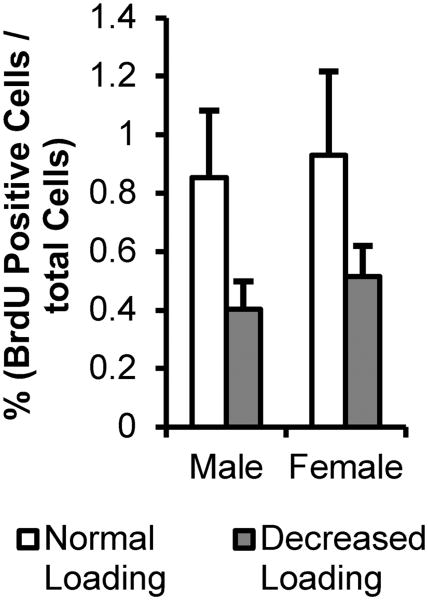

3.2 Decreased occlusal loading induced Gene expression analysis and Immunohistochemistry of the TMJ

In male and female ER beta KO mice, decreased occlusal loading caused a significant decrease in Collagen type X expression (p<0.05) compared with normal loading controls (Figure 3). Only in female ER beta KO mice, Pthrp expression was significantly decreased (p<0.05) by decreased occlusal loading, but not in male ER beta KO mice. There was no significant change on the expression of Ihh, Col 2 and Sox9 in both male and female KO mice with the treatment.

Figure 3.

21-day old female and male ER beta KO mice were exposed to normal and decreased occlusal loading (incisor trimming and soft diet administration) for 4 weeks. Real Time PCR analysis was performed for Parathyroid Hormone Related Protein (Pthrp), SRY-box containing gene 9 (Sox9), Collagen type II (Col 2), Indian Hedgehog (Ihh), and Collagen Type X (Col 10) gene expression from the mandibular condylar head. Values are the means and SEM for n=6 mice per group. *Significant difference between decreased occlusal loading and normal loading (p< 0.05).

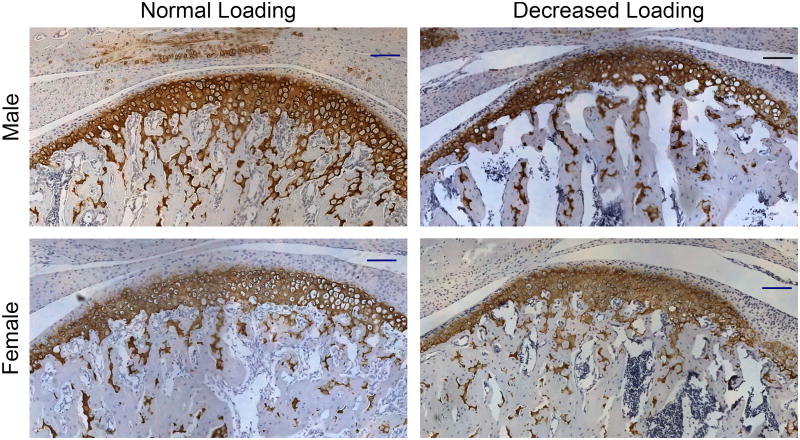

No difference was found in the ratio of Col 2 positive expression area/total condylar cartilage area with decreased occlusal loading, for both male and female ER beta KO mice (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Col 2 Immunohistochemistry was performed on the mandibular condyles of female and male ER beta KO mice exposed to normal and decreased occlusal loading for 4 weeks. The Col 2 positive area was stained brown. Bars = 100μm. (10× magnification)

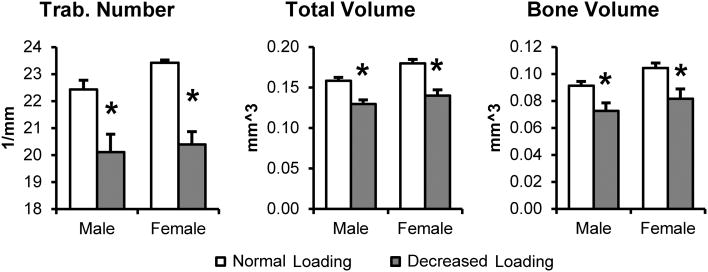

3.3 Subchondral bone analysis

We found that in female ER beta KO mice, decreased occlusal loading caused a significant decrease in total volume (p<0.01), bone volume (p<0.05), and trabecular number (p<0.001) when compared with normal loading controls (Figure 5). We also found similar results in male ER beta KO mice, in which decreased occlusal loading caused a significant decrease in total volume (p<0.01), bone volume (p<0.05), and trabecular number (p<0.05) when compared with normal loading controls (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Micro-CT analysis of the subchondral bone from male and female 21-day old ER beta mice exposed to 4 weeks of normal loading or decreased occlusal loading. Analysis of trabecular number, total volume, and bone volume. Values are the means and SEM for n=6-7 mice per group. Significant difference between decreased occlusal loading and normal loading (p< 0.05).

4. Discussion

Unlike other articular joints, in humans, the TMJ undergoes endochondral ossification and remodels to mechanical and hormonal cues until 18-30 years of age (13, 14). The four zones of the mandibular condylar cartilage (superficial, polymorphic, flattened, and hypertrophic) are highly organized and originate from the progressive differentiation of a finite number of progenitor cells in the polymorphic zone. These progenitor cells then migrate to the flattened zone and later the hypertrophic zone, where they undergo terminal maturation (15). The various zones are marked by differential expression of chondrocyte maturation markers. For example, cells in the superficial zone express Proteoglycan 4 (Prg4); cells in the polymorphic zone express SRY-box containing gene 9 (Sox9), Parathyroid hormone-related protein (Pthrp), and are highly proliferative; cells in the flattened zone express Collagen type II (Col 2); and cells in the hypertrophic zone express Indian Hedgehog (Ihh) and Collagen type X (Col 10) (15). It is difficult to delineate the zones by examination of H&E staining. Therefore, we decided to demarcate the mandibular condylar cartilage by cell size and divide it into non-hypertrophic layer hypertrophic layer as described in Materials and Methods.

In both male and female ER beta KO mice, we found that decrease occlusal loading caused a reduction in the thickness of the non-hypertrophic layer. However, decreased occlusal loading did not cause a corresponding decrease in proliferation. One of the reasons could be due to the way we measured proliferation. In this study we injected BrdU 3 hours prior to sacrifice, whereas in other studies, investigators have injected EdU (thymidine analogue) 24 hours prior to sacrifice (16). Therefore, it maybe possible that decreased occlusal loading only affects cells that are slowly dividing and need a longer exposure to thymidine analogue labeling to be detected. Future studies with longer duration of BrdU or EdU labeling are needed in order to clarify this issue.

In this study we found, unlike female WT mice, that decreased occlusal loading in female ER beta KO mice did not cause decreased expression of Sox9 and Collagen type II. We have previously observed that estrogen via the estrogen receptor beta pathway promotes proliferative pool exit and subsequent chondrocyte hypertrophy (11). Therefore, in our working model, we posit that the naturally higher levels of estrogen in females activate the estrogen receptor beta pathway, causing cells to enter hypertrophy. We believe that this estrogen dependent cell transition causes a decrease in Col 2, in female wt mice exposed to decreased occlusal loading (1, 7), but not in male wt, female ER beta KO and male ER beta KO mice. Another explanation might be due to unopposed estrogen receptor alpha signaling. In other tissues ER alpha and ER beta counter each other (17). A similar phenomenon may also occur in the mandibular condylar cartilage. For example, we found that estrogen treatment caused an increase in Col 2 expression in ovariectomized ER beta KO mice but not in ovariectomized WT mice (18). Therefore, lack of decreased occlusal induced inhibition of Col 2 expression in female ER beta KO mice, may also be due to unopposed ER alpha activity. Future studies are needed in clarifying this subject.

We found that in male ER beta KO mice, similar to male WT mice, decreased occlusal loading only caused a decrease in Col 10 expression. The fact that both the male and female WT and ER beta KO mice exhibited a significant decrease in Col 10 expression, following exposure to decreased occlusal loading, implies that an estrogen independent mechanism is involved. Furthermore, the similar response of male WT and ER beta KO mice to decreased loading suggests that, like other growth plate cartilages (19), ER beta deficiency causes a phenotype in the temporomandibular joints of female mice exclusively.

The subchondral bones of both male and female ER beta KO mice were equally affected by decreased occlusal loading; both exhibited decreased subchondral bone volume as a result of decreased trabecular number. In our previous study, similar results were observed in the WT mice exposed to decreased loading, with the exception of a significant increase in trabecular spacing in both the male and female C57BL/6 WT mice (1). The differences observed between the WT and ER beta KO mice may be explained by the fact that ER beta KO mice have fewer osteoclasts compared with WT mice (20).

In conclusion, we found that decreased occlusal loading induced inhibition of early chondrocyte maturation markers in female mice was attenuated by ER beta deficiency. A greater understanding of the role of estrogen in regulating mechanical loading-induced TMJ remodeling is critical in order to explain the sex predilection of TMJ diseases.

Highlights.

We examined TMJ of male and female ER beta KO mice exposed to decreased occlusal loading.

Decreased occlusal loading triggered similar effects in male and female ER beta KO mice, which is different from wild type mice.

ER beta deficiency attenuates sex differences in chondrocyte maturation markers (Sox9 and Col2) caused by decreased occlusal loading.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by 1R01DE020097 (SW) from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institute of Health.

Footnotes

Competing interests: All authors have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: All experiments were performed in accordance with animal welfare based on an approved IACUC protocol #AAAD0950 from the Columbia University animal care committee.

Author contribution: I. Polur, Y. Kamiya, M. Xu, B. Cabri, and M. Alshabeeb were involved in data collection, drafting and approval of the manuscript.

S. Wadhwa and J. Chen were involved in study design, data analysis, drafting and approval of the manuscript.

S. Wadhwa and J. Chen take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Ilona Polur, Email: ip2162@columbia.edu.

Yosuke Kamiya, Email: kamisuke816@gmail.com.

Manshan Xu, Email: mx2137@cumc.columbia.edu.

Bianca S. Cabri, Email: bsc2126@cumc.columbia.edu.

Marwa Alshabeeb, Email: ma3315@columbia.edu.

Sunil Wadhwa, Email: sw2680@cumc.columbia.edu.

Jing Chen, Email: jc3835@cumc.columbia.edu.

References

- 1.Chen J, Sobue T, Utreja A, Kalajzic Z, Xu M, Kilts T, Young M, Wadhwa S. Sex differences in chondrocyte maturation in the mandibular condyle from a decreased occlusal loading model. Calcif Tissue Int. 2011;89(2):123–9. doi: 10.1007/s00223-011-9498-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manfredini D, Guarda-Nardini L, Winocur E, Piccotti F, Ahlberg J, Lobbezoo F. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review of axis I epidemiologic findings. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112(4):453–62. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manfredini D, Arveda N, Guarda-Nardini L, Segu M, Collesano V. Distribution of diagnoses in a population of patients with temporomandibular disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114(5):e35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manfredini D, Piccotti F, Ferronato G, Guarda-Nardini L. Age peaks of different RDC/TMD diagnoses in a patient population. J Dent. 2010;38(5):392–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanaka E, Detamore MS, Mercuri LG. Degenerative disorders of the temporomandibular joint: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Journal of dental research. 2008;87(4):296–307. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milam SB. Pathogenesis of degenerative temporomandibular joint arthritides. Odontology. 2005;93(1):7–15. doi: 10.1007/s10266-005-0056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen J, Sorensen KP, Gupta T, Kilts T, Young M, Wadhwa S. Altered functional loading causes differential effects in the subchondral bone and condylar cartilage in the temporomandibular joint from young mice. Osteoarthritis and cartilage/OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2009;17(3):354–61. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borjesson AE, Lagerquist MK, Windahl SH, Ohlsson C. The role of estrogen receptor alpha in the regulation of bone and growth plate cartilage. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70(21):4023–37. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1317-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chagin AS, Lindberg MK, Andersson N, Moverare S, Gustafsson JA, Savendahl L, Ohlsson C. Estrogen receptor-beta inhibits skeletal growth and has the capacity to mediate growth plate fusion in female mice. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2004;19(1):72–7. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.0301203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chagin AS, Savendahl L. Oestrogen receptors and linear bone growth. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96(9):1275–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamiya Y, Chen J, Xu M, Utreja A, Choi T, Drissi H, Wadhwa S. Increased mandibular condylar growth in mice with estrogen receptor beta deficiency. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2013;28(5):1127–34. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ness AR. Eruption rates of impeded and unimpeded mandibular incisors of the adult laboratory mouse. Arch Oral Biol. 1965;10(3):439–51. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(65)90109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luder HU. Articular degeneration and remodeling in human temporomandibular joints with normal and abnormal disc position. Journal of orofacial pain. 1993;7(4):391–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luder HU. Age changes in the articular tissue of human mandibular condyles from adolescence to old age: a semiquantitative light microscopic study. Anat Rec. 1998;251(4):439–47. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199808)251:4<439::AID-AR3>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shibukawa Y, Young B, Wu C, Yamada S, Long F, Pacifici M, et al. Temporomandibular joint formation and condyle growth require Indian hedgehog signaling. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2007;236(2):426–34. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koyama E, Saunders C, Salhab I, Decker RS, Chen I, Um H, et al. Lubricin is Required for the Structural Integrity and Post-natal Maintenance of TMJ. Journal of dental research. 2014;93(7):663–70. doi: 10.1177/0022034514535807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindberg MK, Moverare S, Skrtic S, Gao H, Dahlman-Wright K, Gustafsson JA, et al. Estrogen receptor (ER)-beta reduces ERalpha-regulated gene transcription, supporting a “ying yang” relationship between ERalpha and ERbeta in mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17(2):203–8. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J, Kamiya Y, Polur I, Xu M, Choi T, Kalajzic Z, Drissi H, Wadhwa S. Estrogen via estrogen receptor beta partially inhibits mandibular condylar cartilage growth. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.07.003. Epub 2014 Jul 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Windahl SH, Hollberg K, Vidal O, Gustafsson JA, Ohlsson C, Andersson G. Female estrogen receptor beta-/- mice are partially protected against age-related trabecular bone loss. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2001;16(8):1388–98. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.8.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Windahl SH, Vidal O, Andersson G, Gustafsson JA, Ohlsson C. Increased cortical bone mineral content but unchanged trabecular bone mineral density in female ERbeta (-/-) mice. J Clin Invest. 1999;104(7):895–901. doi: 10.1172/JCI6730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]