Abstract

Background

Use of antiretroviral (ARV) drugs during pregnancy has been associated with an increased risk of birth defects, but the evidence remains inconclusive.

Methods

We identified infants born to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected mothers between 1994 and 2009 using Tennessee Medicaid data linked to vital records. Maternal HIV status was based on diagnosis codes, prescriptions for ARVs, and HIV-related laboratory testing. ARV exposure was identified from pharmacy claims. Birth defects diagnoses during the first year of life were identified from maternal and infant claims, and from vital records, and were confirmed through medical record review. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to evaluate associations between first trimester ARV dispensing and birth defects.

Results

Of 806 infants included in the study, 32 (4.0%) had at least 1 major birth defect, most (44%) in the cardiac system. There was no increased risk for infants exposed in the first trimester to ARVs compared to unexposed infants (odds ratio = 1.07; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.50 – 2.31). Of the 20 infants exposed to efavirenz (EFV), none had a birth defect (0%; 95% CI: 0.0 – 13.2).

Conclusions

There was no significant association between first trimester ARV dispensing and the risk of birth defects in this Medicaid cohort of HIV positive women.

Keywords: antiretroviral, birth defects, HIV, Medicaid

More than 3 million human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected women worldwide give birth each year [1], and an increasing number conceive while receiving antiretroviral (ARV) treatment for their own infection or to prevent mother-to-child transmission (MTCT). Yet, the fetal safety of many of the currently approved ARV medications for use in non-pregnant adult populations is largely unknown. ARVs are associated with numerous toxicities in both adults and children [2, 3], and therefore it seems biologically plausible that they would also be toxic to the developing fetus. Until recently, data on the potential teratogenic effect of ARVs had mainly been obtained from animal studies [4], case reports [5, 6], and surveillance data [7]. Nowadays, we do have the results provided by several cohort studies [8–15], but the evidence to date is still limited by differences in the definition and ascertainment of cases across the studies and variations in the selection of control groups. Moreover, some of the studies included a selective sample of relatively healthy participants. Thus, there is a compelling need to have further safety data for the use of ARVs during pregnancy, particularly for disadvantaged populations often neglected by volunteered based research. Large health care utilization databases are an efficient resource for conducting population-based studies with valid reference groups [16–18]. We therefore used data from the Tennessee Medicaid Program (TennCare), linked to vital records and supplemented by in-depth medical chart reviews, to assess the risk of birth defects after in utero exposure to ARVs among infants born to HIV-infected women enrolled in TennCare between 1994 and 2009. Key elements of the database have been validated and these data have been used to conduct several epidemiologic studies of medications in pregnancy [19–22].

METHODS

Study Population

The study source population consisted of all infants, including stillbirths, who were born between January 1, 1994 and December 31, 2009 to HIV-infected women enrolled in TennCare. We classified a woman as being HIV-infected if she had confirmation of HIV infection or ARV use between 365 days prior to her last menstrual period (LMP) and delivery. HIV infection was determined based on an algorithm that required codes for HIV diagnosis, HIV related laboratory testing (CD4 count or HIV viral load), or prescription dispensing for ARVs. We obtained HIV diagnosis codes (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] codes: 042, 043, 044, V08, 795.8 in years prior to 2007 only, 079.53, or 795.71) and laboratory testing codes (Current Procedural Terminology [CPT] codes: 86360, 86361, or 87536) from inpatient and outpatient claims; information on ARV prescription dispensing was obtained from pharmacy records. A comprehensive review of a random sample of medical charts for the women identified as HIV-infected using our algorithm yielded a positive predictive value (PPV) of 94%.

Infants were included in our analysis if their mothers had prescription drug coverage from at least 30 days before their LMP to delivery. In addition, we also required infants to have been enrolled in TennCare within the first 30 days of life and for at least 90 days in order to identify most major birth defects [23]. As shown in a previous study, over 90% of infants enrolled in TennCare meet this requirement [19]. To maximize case ascertainment for major birth defects, we included all claims prior to the first birthday of infants meeting the inclusion criteria. We also included multiple pregnancies for a mother if enrollment requirements were met. In multiple gestations infants were included independently.

Permission to use TennCare data was obtained from the Tennessee Department of Health and the TennCare Bureau. The study was reviewed and approved by Harvard School of Public Health and Vanderbilt University institutional review boards.

ARV Exposure

We identified prescriptions for ARVs from the mothers’ Medicaid pharmacy claims. An infant was considered to have been exposed in utero to a specific ARV or ARV drug class if the mother had at least one prescription dispensing for that ARV from 30 days prior to the LMP through delivery. Trimester exposures were also based on at least one prescription dispensing during the specific trimester. We defined first trimester as LMP to 90 days gestation; second trimester as 91 to 179 days gestation; and third trimester as 180 days to delivery. The LMP date was identified from birth certificate files for 82% of pregnancies in the study cohort. For 17% of the pregnancies the LMP date and gestational age at birth were missing from the birth certificates and we estimated LMP from the birth weight of the infant using a validated algorithm based on the birthweight-for-gestational age distribution in the TennCare population and accounting for calendar year of birth and maternal race [24]. In 1% of pregnancies with missing birth weight, we estimated LMP as delivery date minus 270 days.

All infants were classified according to first trimester maternal ARV use (overall and by ARV class), since this is the most etiologically relevant period for birth defects. We also classified infants according to use in all three trimesters and identified the trimester in which the first ARV prescription occurred (first trimester, second or third trimester, or never exposed).

Identification and Classification of Birth Defects

Our outcome of interest was the presence of a confirmed, major birth defect not related to a chromosomal anomaly or perinatal conditions associated with prematurity [25, 26]. We used a 3-stage process to identify, confirm and classify infants with a birth defect. First we utilized ICD-9-CM codes (740 to 759) for birth defects to identify potential cases from maternal diagnosis claims (delivery through 90 days postpartum), infant diagnosis claims (birth through the first birthday), information from birth certificate checkbox data, fetal death certificate (after 20 weeks of gestation), and death certificate causes of death (for deaths occurring before the first birthday). Second, to verify and confirm each diagnosis, the study research nurses, blinded to ARV exposure, reviewed the medical charts of all potential cases and then copied pertinent information to a standardized chart review abstraction form. Two study physicians, also blinded to ARV exposure, independently reviewed all the potential cases using a standardized outcome adjudication form to determine the final case status and diagnosis of each infant. Case status was classified as either confirmed, or not a case. Any ambiguous cases or disagreements were resolved by the two primary investigators of the study. We considered all potential defects within the same infant. Finally, to classify the confirmed malformations into major versus minor defects, we used the classification system outlined in the Metropolitan Atlanta Congenital Defects Program (MACDP) guidelines [27]. For all other infants who were not identified as potential cases based on ICD-9-CM codes for birth defects, we took a random sample of 50 to also verify and confirm that they were true non-cases and found that 49 (98%) had no evidence of a birth defect in the medical record; one had postaxial polydactyly.

Study Covariates

Study covariates were chosen based on known risk factors for birth defects and potential confounders for their association with ARV use during pregnancy. We obtained information on demographic and lifestyle factors from birth certificate files; clinical information came from Medicaid inpatient and outpatient diagnosis claims; and information on non-ARV prescription dispensing was obtained from Medicaid pharmacy claims.

Statistical Analysis

We compared maternal demographic, reproductive and medical characteristics for infants whose mothers received their first ARV prescription dispensing during the first trimester, to those with first dispensing in the second or third trimester, and those who were never exposed to ARVs in utero. We used the χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon test for continuous variables. Unadjusted logistic regression models were used to assess the potential risk factors for birth defects. All variables with a 2-sided P-value < .10 in the univariable analysis were included in the multivariable logistic regression models. We assessed the risk of birth defects according to first trimester exposure to any ARV or to specific ARV classes versus no exposure in the first trimester, and then also evaluated the risk according to the trimester in which the first ARV prescription dispensing occurred. To control for temporal trends of ARV use, we included the calendar year of delivery in the final regression models. We also adjusted for maternal age and race regardless of whether the variables were significant in the univariable analyses in order to account for their reported association with birth defects in past studies [28, 29]. Unadjusted and adjusted regression models were fit using generalized estimating equations (GEE) to account for clustering of multiple pregnancies in a woman (sibling or multiple gestation births) during the study period. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Sensitivity analysis

Since neither CD4+ cell count nor viral load are recorded in claims data, in order to assess potential differences in maternal HIV disease severity for infants with birth defects compared to those without, we obtained information on CD4+ cell count from the medical charts of all confirmed major cases and the random sample of 50 non-cases; we did not have sufficient information to assess viral load. The laboratory values of CD4+ cell count closest to the LMP date were used to compare mean values among cases versus non-cases.

RESULTS

Of the 806 live born infants included in the study, 671 (83%) had maternal ARV prescription dispensing during pregnancy. Of these, 221 (33%) had first dispensing in the first trimester, and 450 (67%) had first dispensing in the second or third trimester; 135 infants (17%) were unexposed throughout pregnancy (Table 1). Infants that were exposed to ARVs in the first trimester, compared to those exposed only in the second or third trimester or not exposed to ARVs in utero, were more likely to have had early maternal prenatal care (defined as prenatal care in the first or second trimester). Furthermore, these infants were more likely to have mothers with the following characteristics during pregnancy: HIV-related illnesses, AIDS diagnosis, cotrimoxazole prescriptions in the first trimester and prescriptions for non-ARV medications.

Table 1.

Characteristics of pregnancies according to maternal timing of earliest ARV prescription dispensing during pregnancy (N= 806 infantsa)

| Characteristic | Timing of the first ARV prescription dispensing

|

P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Trimester (N = 221) | 2nd/3rd Trimester (N = 450) | No ARV (N = 135) | ||

| Year of delivery, no (%) | 0.03 | |||

| 1994 – 1998 | 35 (16%) | 121 (27%) | 38 (28%) | |

| 1999 – 2002 | 76 (34%) | 145 (32%) | 49 (36%) | |

| 2003 – 2006 | 70 (32%) | 110 (24%) | 29 (21%) | |

| 2007 – 2009 | 40 (18%) | 74 (16%) | 19 (14%) | |

| Age, median (range) | 27 (14 – 43) | 25 (15 – 43) | 26 (16 – 40) | <.0001 |

| Race, no (%) | 0.02 | |||

| Black | 169 (76%) | 386 (86%) | 113 (84%) | |

| White | 52 (24%) | 63 (14%) | 22 (22%) | |

| Other | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Education, no (%) | 0.38 | |||

| ≤12 | 184 (83%) | 387 (86%) | 119 (88%) | |

| >12 | 37 (17%) | 61 (14%) | 16 (12%) | |

| Parity, mean (25th – 75th) | 2 (1 – 3) | 2 (1 – 3) | 3 (1 – 4) | 0.0016 |

| Trimester prenatal care began, no (%) | <.0001 | |||

| None | 6 (3%) | 13 (3%) | 28 (22%) | |

| 1st | 141 (67%) | 239 (55%) | 55 (43%) | |

| 2nd | 57 (27%) | 151 (35%) | 31 (24%) | |

| 3rd | 7 (3%) | 32 (7%) | 13 (10%) | |

| Number of prenatal visits among those with at least one visit, median (range) | 10 (1 – 28) | 10 (1– 37) | 10 (1 – 21) | <.0001 |

| Chronic health diagnosis b, no (%) | 62 (28%) | 130 (29%) | 47 (35%) | 0.35 |

| Non-ARV medication use during pregnancy c, no (%) | 106 (48%) | 169 (38%) | 28 (21%) | <.0001 |

| Possibly HIV-related maternal illnesses d, no (%) | 112 (51%) | 199 (44%) | 28 (21%) | <.0001 |

| AIDS diagnosis during pregnancy, no (%) | 141 (64%) | 209 (46%) | 22 (16%) | <.0001 |

| Cotrimoxazole use in the 1st trimester, no (%) | 65 (29%) | 40 (9%) | 5 (4%) | <.0001 |

| Tobacco use, no (%) | 58 (26%) | 106 (24%) | 38 (28%) | 0.49 |

ARV: antiretroviral.

Infants from multiple gestation pregnancies (20 sets of twins) were counted individually even though they share the same pregnancy exposure

Chronic health diagnoses (LMP-180 days through delivery) defined as having at least one of the following conditions: epilepsy, sickle cell disease, asthma, renal disease, neoplastic disease, cardiac disease, hypertension, cystic fibrosis, substance abuse, alcohol abuse, mental health disorders, cerebrovascular disease, obesity, migraine, sexually transmitted infection, or hepatitis

Non-ARV medication use during pregnancy (LMP through delivery) defined as having a prescription for at least one of the following: androgens, ACE inhibitors, non ACEI-antihypertensive, anticoagulants, anticonvulsants, lithium, anti-infectives, estrogens, GI agents, thyroid agents, vitamin A, statins, other drugs, diabetes medications, asthma, neoplastic disease, mental health disorders, or migraine.

Possibly HIV-related illnesses (LMP through delivery) defined as having at least one of the following conditions: pneumocystis pneumonia, tuberculosis, Kaposi’s sarcoma, cytomegalovirus infection, toxoplasmosis, HIV encephalopathy, cryptosporidiosis, isosporiasis, histoplasmosis, coccidiomycosis, lymphoma, weight loss, mycobacterial infection, nephropathy, cardiomyopathy, or diarrhea

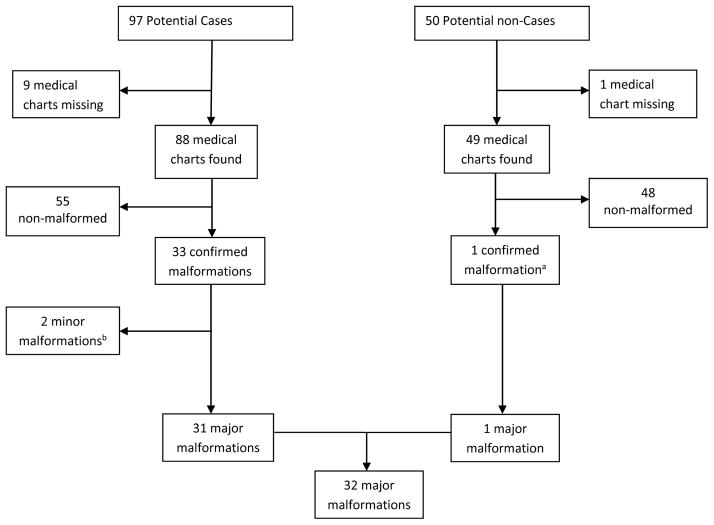

We identified 97 potential cases with ICD-9-CM codes for birth defects. From these infants, 88 (91%) medical charts were found and we confirmed 33 malformations (PPV = 37.5%) [Figure 1]. (It should be noted that the low PPV is due to the unrestrictive definition applied to define “potential cases”, which was used to maximize sensitivity since we were going to conduct a subsequent medical record review to prioritize specificity). For the 9 infants whose charts were not found, we classified them as non-malformed since we would expect approximately 3 confirmed major malformations based on the PPV. In a sensitivity analysis, reclassification of all 9 infants as major cases did not change any of our results. Major birth defects were identified in 31 of the 33 infants confirmed to be true cases and 1 infant from the 50 potential non-cases, resulting in an overall prevalence of 4.0% (95% CI: 2.6 – 5.3). Details of the confirmed major defects for the 32 infants are shown in a Table in the Supplemental Digital Content. The two remaining infants from the 33 confirmed to be true cases only had minor birth defects - congenital ptosis and atrial septal defect [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Validation and Classification of Malformations

aThis was an infant with neonatal intensive care unit admission found to have an extra appendage (ligated in nursery) next to left fifth finger.

bThe 2 minor malformations were: congenital ptosis (1) and atrial septal defect (1)

There were no statistically significant differences in the risk of birth defects for infants exposed to ARVs in the first trimester, overall (OR = 1.07; 95% CI: 0.50 – 2.31) or by drug class, compared to those not exposed in the first trimester (Table 2). The prevalence of birth defects according to the trimester in which the first ARV prescription occurred was lowest among infants who were never exposed in utero (2.2%) compared to those exposed for the first time in the first trimester (4.1%) or second/third trimester (4.4%) (Table 3). The odds ratio for birth defects for first trimester dispensing compared to never exposed in utero was 1.90 (95% CI: 0.49 – 7.30). This odds ratio was similar for infants exposed in the second or third trimester compared to those never exposed.

Table 2.

Risk of birth defects according to first trimester dispensing of any ARV or specific ARV class (N= 806 Infants)

| Exposure Group | Na | Birth Defect (N = 32) | % Prevalence | Adjusted ORb (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unexposed | ||||

| Any ARV | 585 | 23 | 3.9 | ref |

| Exposed | ||||

| Any ARV | 221 | 9 | 4.1 | 1.07 (0.50, 2.31) |

| NRTIs | 217 | 9 | 4.1 | 1.09 (0.51, 2.34) |

| NNRTIs | 50 | 0 | 0 | --- |

| PIs | 89 | 5 | 5.6 | 1.76 (0.62, 4.94) |

ARV: antiretroviral; NRTIs: nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; NNRTIs: non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; PIs: protease inhibitors; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval

These are non-mutually exclusive groups

Logistic regression models adjusted for calendar year of delivery (categorical), maternal age (continuous) and race (categorical) were utilized.

Table 3.

Risk of birth defects according to trimester in which first ARV prescription dispensing occurred (N= 806 Infants)

| Trimester of Exposure | Prevalence of birth defects

|

Adjusted Model 1b OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted Model 2b OR (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na | % | 95% CI | |||

| 1st trimester | 9/221 | 4.07 | 1.5 – 6.7 | 1.90 (0.49,7.30) | 0.94 (0.43, 2.05) |

| 2nd or 3rd trimester | 20/450 | 4.44 | 2.5 – 6.3 | 2.02 (0.59, 6.85) | ref |

| Never exposed | 3/135 | 2.22 | 0.0 – 4.7 | ref | 0.50 (0.15, 1.69) |

ARV: antiretroviral; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval

Number of births with at least 1 defect/number of infants exposed during the trimester

Logistic regression models adjusted for calendar year of delivery (categorical), maternal age (continuous) and race (categorical) were utilized.

For in utero exposure to specific ARVs during the first trimester, the numbers were small and the estimates unstable (Table 4). Among the 20 infants who were exposed to efavirenz (EFV), none had a birth defect (0%; 95% CI: 0.0–13.2).

Table 4.

Prevalence of birth defects according to ARV prescription dispensing during the first trimester (N= 806 Infants)

| Type of Antiretroviral (ARV) | Total (%) Exposed | Total (%)with Birth Defect

|

Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposed | Unexposed | |||

|

| ||||

| Any Antiretroviral | 221 (27) | 9 (4.1) | 23 (3.9) | 1.07 (0.50, 2.31) |

|

| ||||

| Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTIs) | 217 (27) | 9 (4.2) | 23 (3.9) | 1.10 (0.51, 2.36) |

| Zidovudine (ZDV) b | 156 (19) | 7 (4.5) | 25 (3.9) | 1.23 (0.54, 2.82) |

| Lamivudine (3TC) c | 158 (20) | 8 (5.1) | 24 (3.7) | 1.53 (0.68, 3.41) |

| Stavudine (d4T) | 31 (4) | 0 (0.0) | 32 (4.1) | |

| Emtricitabine (FTC) d | 23 (3) | 1 (4.3) | 31 (4.0) | 0.91 (0.08, 10.19) |

| Tenofovir (TDF) d | 28 (3) | 0 (0.0) | 32 (4.1) | |

| Other NRTIs f | 57 (7) | 4 (7.0) | 28 (3.7) | 2.11 (0.76, 5.86) |

|

| ||||

| Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTIs) | 50 (6) | 0 (0.0) | 32 (4.2) | |

| Nevirapine (NVP) | 34 (4) | 0 (0.0) | 32 (4.2) | |

| Efavirenz (EFV) e | 20 (2) | 0 (0.0) | 32 (4.1) | |

| Other NNRTIs g | 0 (0) | 0 (0.0) | 32 (4.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Protease Inhibitors (PIs) | 89 (11) | 5 (5.6) | 27 (3.8) | 1.76 (0.64, 4.82) |

| Lopinavir/Ritonavir (LPV/RTV) | 12 (1) | 0 (0.0) | 32 (4.0) | |

| Nelfinavir (NFV) | 51 (6) | 3 (5.9) | 29 (3.8) | 1.58 (0.47, 5.31) |

| Other PIs h | 30 (4) | 2 (6.7) | 30 (3.9) | 2.24 (0.55, 9.16) |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval

Logistic regression models adjusted for calendar year of delivery (categorical), maternal age (continuous) and race (categorical) were utilized. Some values for adjusted ORs are missing (e.g. all NNRTIs) because there were no exposed infants with birth defects and therefore ORs could not be calculated.

Includes Combivir and Trizivir

Includes Combivir, Epzicom and Trizivir

Includes Atripla and Truvada

Includes Atripla

Abacavir (includes Trizivir), Epzicom, Didanosine, Zalcitabine

Delavirdine, Etravirine

Amprenavir, Atazanavir, Darunavir, Fosamprenavir, Indinavir, Ritonavir, Saquinavir, Tipranavir

Note 1: 1 infant (with no malformation) was exposed to other ARV class (Maraviroc)

Results from the analysis of the association between HIV disease severity and major birth defects showed no difference in maternal mean CD4+ cell count for infants with major malformations (461 cells/mm3, N=13 infants) compared to those with no malformations (471 cells/mm3, N=27 infants).

DISCUSSION

In this cohort of 806 infants born to HIV-infected women enrolled in Tennessee Medicaid between 1994 and 2009, 32 (4.0%) had at least 1 major malformation. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of any major malformations between infants who were exposed to ARVs in the first trimester compared to those only exposed later in pregnancy or those never exposed throughout pregnancy. We found no statistically significant association for first trimester exposure to ARVs overall or by drug class and the risk of any major malformations.

The prevalence of major malformations in our study population was slightly higher than current estimates from the general United States pediatric population (3%) [30] and findings from studies conducted among HIV-infected pregnant women in the US and Europe [9, 14], including the most recent estimate of 2.9% from the Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry [7]. However, compared to four studies in the US and international cohorts that were published in the past two years, the prevalence of birth defects in our study was slightly lower [10–13]. These four studies reported overall prevalence that ranged from 4.7% to 6.2%, reflecting differences that are likely due to variations in the case definition and ascertainment. For example, in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) International Site Development Initiative (NISDI) Study [11] which reported the highest overall prevalence of 6.2%, both stillbirths and infants with chromosomal abnormalities were included in the case definition, unlike in our study. The Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group protocols 219 and 219C (PACTG 219/219C) study [10] had echocardiograms, per study protocol, for approximately 30% of the children in their cohort. As the study authors noted, this may lead to a prevalence of cardiac defects 5% to 10% higher than that in regular clinical practice. While some studies explicitly differentiated major versus minor birth defects and reported the numbers for each category, others, for example the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group protocol P1025 (IMPAACT P1025) study [12], did not state whether they made this distinction. This information is crucial to compare results across studies. Had our study included both major and minor malformations, the reported prevalence would have been 4.2%. Furthermore, the 3-stage validation process that we employed prioritized specificity and therefore the validity of our relative risk estimates, at the cost of sensitivity. Therefore, our final case number was small and could have slightly underestimate the true prevalence of birth defects in our study population.

The estimated relative risk of birth defects among those with first trimester exposure to any ARVs compared to those unexposed to ARVs during the first trimester in our study (OR= 1.07; 95% CI: 0.50 – 2.31) was similar to that reported in the PACTG 219/219C study (OR= 1.10; 95% CI: 0.72 – 1.67) [10]. These findings suggest no or limited teratogenic effect for ARVs overall. However, a few studies did find an association between exposure to individual ARVs and risk of birth defects [10, 12, 14]. Of note, the PACTG 219/219C [10] and the IMPAACT P1025 [12] were the first population-based studies to find an association between EFV and birth defects, although EFV has been classified as FDA pregnancy category D (positive evidence of risk) since 2005 based on evidence from multiple case reports and results from animal studies [31]. Among the 20 infants with first trimester exposure to EFV in our study, none had a birth defect.

Our study had several limitations. First, we did not have detailed clinical information on maternal HIV disease severity since these are not available in health care utilization databases. However, we obtained information on CD4+ cell count from a sample of medical charts and found no association with birth defects, suggesting there is not substantial confounding by disease severity. Moreover, previous studies with information on maternal viral load, a strong indicator for HIV disease severity, did not observe an association between this marker and the risk of birth defects [11, 12]. Second, we ascertained first trimester ARV exposure based on drug dispensing which could lead to exposure misclassification (i.e., filling a prescription does not guarantee that the medication was actually taken). Third, given our sample of 806 mother-infant pairs and the low frequency of specific malformations (in the order of 1 per 1000 births or lower), we had limited power to evaluate specific birth defects. Moreover, given the infrequent use of specific ARV in the population, we had limited power to study the safety of specific drugs.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to assess the association between in utero ARV exposure and birth defects using electronic health care data, supplemented by in-depth medical chart reviews of all potential cases and a subsample of non-cases. The data reflects real clinical practice in the US, compared to other studies previously conducted in volunteers. While Medicaid recipients represent a disadvantaged, poorer population of the country, the program is the single largest source of health care coverage for people living with HIV [32] and covers medical expenses for over 40% of all births in the Nation [33]. Future studies could combine several similar health care databases, for example Medicaid data from different states, to increase the study sample size and power to better define the safety boundaries for specific ARVs.

In conclusion, our analysis did not detect an increased risk of birth defects associated with first trimester ARV dispensing in a cohort of infants born to HIV-infected women enrolled in Medicaid.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child and Human Development (NICHD) [R01HD056940-01]

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of our research coordinator, Shannon Stratton, together with our study nurses, Patricia Gideon, RN; Leanne Balmer, MSN, RN; Michelle DeRanieri, RN, MSN, as well as the nurses who work at the individual hospitals where the women in our study delivered their babies. We are also grateful to the Tennessee Department of Health and the TennCare Bureau for permitting the use of this data, as well as the institutional review boards at the Harvard School of Public Health and Vanderbilt University.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest

SHD has consulted for Novartis, AstraZeneca and GSK. All other authors do not have any commercial or other association that might pose a conflict of interest

Meetings where the information has been presented

First trimester exposure to antiretroviral therapy and risk of birth defects among infants born to HIV-infected women on Tennessee Medicaid Program. Poster presentation: 4th International Workshop of HIV Pediatrics. July 20–21, 2012; abstract no. P_21. Washington DC, USA

References

- 1.Gray GE, McIntyre JA. HIV and pregnancy. BMJ. 2007;334:950–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39176.674977.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children. [Accessed December 7, 2012];Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/2/pediatric-arv-guidelines/0. [Table 17a – Table 17l]

- 3.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-infected Adults and Adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services; [Accessed December 7, 2012]. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/1/adult-and-adolescent-arv-guidelines/0. [Table 13] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panel on Treatment of HIV-Infected Pregnant Women and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. [Accessed July 26, 2012];Recommendations for Use of Antiretroviral Drugs in Pregnant HIV-1-Infected Women for Maternal Health and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States. 2011 Sep 14;:1–207. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/3/perinatal-guidelines/0.

- 5.Fundaro C, Genovese O, Rendeli C, Tamburrini E, Salvaggio E. Myelomeningocele in a child with intrauterine exposure to efavirenz. AIDS. 2002;16:299–300. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200201250-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Santis M, Carducci B, De Santis L, Cavaliere AF, Straface G. Periconceptional exposure to efavirenz and neural tube defects. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:355. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry Steering Committee. Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry International Interim Report for 1 January 1989 through 31 January 2012. Wilmington, NC: Registry Coordinating Center; 2012. [Accessed July 23, 2012]. www.APRegistry.com. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bera E, McCausland K, Nonkwelo R, Mgudlwa B, Chacko S, Majeke B. Birth defects following exposure to efavirenz-based antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy: a study at a regional South African hospital. AIDS. 2010;24:283–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328333af32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Townsend CL, Willey BA, Cortina-Borja M, Peckham CS, Tookey PA. Antiretroviral therapy and congenital abnormalities in infants born to HIV-infected women in the UK and Ireland, 1990–2007. AIDS. 2009;23:519–24. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328326ca8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brogly SB, Abzug MJ, Watts DH, et al. Birth defects among children born to human immunodeficiency virus-infected women: pediatric AIDS clinical trials protocols 219 and 219C. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:721–7. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181e74a2f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joao EC, Calvet GA, Krauss MR, et al. Maternal antiretroviral use during pregnancy and infant congenital anomalies: the NISDI perinatal study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:176–85. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c5c81f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knapp KM, Brogly SB, Muenz DG, et al. Prevalence of congenital anomalies in infants with in utero exposure to antiretrovirals. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:164–70. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318235c7aa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watts DH, Huang S, Culnane M, et al. Birth defects among a cohort of infants born to HIV-infected women on antiretroviral medication. J Perinat Med. 2011;39:163–70. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2010.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watts DH, Li D, Handelsman E, et al. Assessment of birth defects according to maternal therapy among infants in the Women and Infants Transmission Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:299–305. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802e2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel D, Thorne C, Fiore S, Newell ML European Collaborative Study. Does highly active antiretroviral therapy increase the risk of congenital abnormalities in HIV-infected women? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40:116–8. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000156854.99769.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ray WA, Griffin MR. Use of Medicaid data for pharmacoepidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:837–49. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ray WA. Population-based studies of adverse drug effects. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1592–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp038145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneeweiss S. Understanding secondary databases: a commentary on “Sources of bias for health state characteristics in secondary databases”. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:648–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper WO, Hernandez-Diaz S, Arbogast PG, et al. Major congenital malformations after first-trimester exposure to ACE inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2443–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper WO, Hernandez-Diaz S, Arbogast PG, et al. Antibiotics potentially used in response to bioterrorism and the risk of major congenital malformations. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2009;23:18–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.00978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper WO, Willy ME, Pont SJ, Ray WA. Increasing use of antidepressants in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:544.e1–544.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper WO, Hernandez-Diaz S, Gideon P, et al. Positive predictive value of computerized records for major congenital malformations. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17:455–60. doi: 10.1002/pds.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erickson JD. Risk factors for birth defects: data from the Atlanta Birth Defects Case-Control Study. Teratology. 1991;43:41–51. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420430106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piper JM, Ray WA, Griffin MR, Fought R, Daughtery JR, Mitchel E., Jr Methodological issues in evaluating expanded Medicaid coverage for pregnant women. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:561–71. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holmes LB, Westgate MN. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for malformations in newborn infants exposed to potential teratogens. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2011;91:807–12. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Birth Defects Prevention Network. NBDPN Guidelines for Conducting Birth Defects Surveillance. Appendix 3.4. [Accessed July 24, 2012];Conditions Related to Prematurity in Infants Born at Less Than 36 Weeks Gestation. http://www.nbdpn.org/birth_defects_surveillance_gui.php.

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Metropolitan Atlanta Congenital Defects Program. [Accessed July 24, 2012];Birth defects and genetic diseases branch 6-digit code for reportable congenital anomalies. http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/documents/MACDPcode0807.pdf.

- 28.Reefhuis J, Honein MA. Maternal age and non-chromosomal birth defects, Atlanta--1968–2000: teenager or thirty-something, who is at risk? Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2004;70:572–9. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kucik JE, Alverson CJ, Gilboa SM, Correa A. Racial/ethnic variations in the prevalence of selected major birth defects, metropolitan Atlanta, 1994–2005. Public Health Rep. 2012;127:52–61. doi: 10.1177/003335491212700106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. [Accessed July 23, 2012];Metropolitan Atlanta Congenital Defects Program (MACDP): Data & Statistics. http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/MACDP.html.

- 31.Mofenson LM. Efavirenz reclassified as FDA pregnancy category D. AIDS Clin Care. 2005;17:17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaiser Family Foundation Fact Sheet. HIV/AIDS Policy. [Accessed December 7, 2012];Medicaid and HIV/AIDS. 2009 Feb; http://www.kff.org/hivaids/upload/7172_04.pdf.

- 33.Maternal and Child Health Update. [Accessed December 7, 2012];Table 6: Medicaid Births as a Percentage of Total Births by State, 2005–2009. 2010 http://www.nga.org/files/live/sites/NGA/files/pdf/MCHUPDATE2010.PDF.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.