ABSTRACT

Enterococcus faecalis is a Gram-positive bacterium that natively colonizes the human gastrointestinal tract and opportunistically causes life-threatening infections. Multidrug-resistant (MDR) E. faecalis strains have emerged, reducing treatment options for these infections. MDR E. faecalis strains have large genomes containing mobile genetic elements (MGEs) that harbor genes for antibiotic resistance and virulence determinants. Bacteria commonly possess genome defense mechanisms to block MGE acquisition, and we hypothesize that these mechanisms have been compromised in MDR E. faecalis. In restriction-modification (R-M) defense, the bacterial genome is methylated at cytosine (C) or adenine (A) residues by a methyltransferase (MTase), such that nonself DNA can be distinguished from self DNA. A cognate restriction endonuclease digests improperly modified nonself DNA. Little is known about R-M in E. faecalis. Here, we use genome resequencing to identify DNA modifications occurring in the oral isolate OG1RF. OG1RF has one of the smallest E. faecalis genomes sequenced to date and possesses few MGEs. Single-molecule real-time (SMRT) and bisulfite sequencing revealed that OG1RF has global 5-methylcytosine (m5C) methylation at 5′-GCWGC-3′ motifs. A type II R-M system confers the m5C modification, and disruption of this system impacts OG1RF electrotransformability and conjugative transfer of an antibiotic resistance plasmid. A second DNA MTase was poorly expressed under laboratory conditions but conferred global N4-methylcytosine (m4C) methylation at 5′-CCGG-3′ motifs when expressed in Escherichia coli. Based on our results, we conclude that R-M can act as a barrier to MGE acquisition and likely influences antibiotic resistance gene dissemination in the E. faecalis species.

IMPORTANCE The horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes among bacteria is a critical public health concern. Enterococcus faecalis is an opportunistic pathogen that causes life-threatening infections in humans. Multidrug resistance acquired by horizontal gene transfer limits treatment options for these infections. In this study, we used innovative DNA sequencing methodologies to investigate how a model strain of E. faecalis discriminates its own DNA from foreign DNA, i.e., self versus nonself discrimination. We also assess the role of an E. faecalis genome modification system in modulating conjugative transfer of an antibiotic resistance plasmid. These results are significant because they demonstrate that differential genome modification impacts horizontal gene transfer frequencies in E. faecalis.

INTRODUCTION

Enterococcus faecalis is a Gram-positive bacterium that natively colonizes the gastrointestinal tracts of humans and other animals (1). It is an opportunistic pathogen that causes life-threatening infections, such as bacteremia and endocarditis in compromised individuals (2). E. faecalis is among the leading causes of hospital-acquired infections in the United States, making it a major public health concern (3). Rising antibiotic resistance in E. faecalis, including resistance to the last-line antibiotic vancomycin, complicates treatment of these infections (2, 4). One way that E. faecalis becomes antibiotic resistant is via the horizontal acquisition of antibiotic resistance genes. These genes are disseminated by mobile genetic elements (MGEs), including integrative conjugative elements, such as Tn916, broad-host-range plasmids, and a group of narrow-host-range plasmids called pheromone-responsive plasmids (5). E. faecalis also acts as a conduit for MGEs harboring antibiotic resistance, transferring them to Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium difficile (6, 7).

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) E. faecalis strains are undergoing genome expansion. E. faecalis OG1RF and V583 are commonly used model strains for Enterococcus studies, and a comparison of their genomes exemplifies this genome expansion. E. faecalis OG1RF is derived from a human caries-associated strain isolated in the early 1970s (8), while the MDR E. faecalis V583 was isolated from the bloodstream of a hospitalized patient in 1987 and was among the first vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus strains identified in the United States (9). The differences in genome sizes and MGE content between OG1RF and V583 are striking: the 3.36-Mb V583 genome possesses 7 prophage and multiple plasmids, transposons, and genomic islands, while the 2.74-Mb OG1RF genome possesses only one Tn916-like element and a prophage that is core to the E. faecalis species (10–12). Among a larger collection of 18 E. faecalis genomes, genome sizes range from 2.74 to 3.36 Mb, with MDR strains enriched for MGE content and having the biggest genomes (13). In general, MDR E. faecalis strains are enriched for horizontally acquired content, including antibiotic resistance genes, virulence factor genes, and metabolic genes potentially important for niche expansion (10, 11, 13–16).

Compromised genome defense, specifically the lack of clustered, regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR-Cas) defense systems, has been hypothesized to play a role in genome expansion in MDR E. faecalis (10, 17). CRISPR-Cas systems confer defense from MGEs via guide RNAs that direct nucleases to invading MGEs with a complementary sequence, providing a type of adaptive immunity against MGEs (18). Among a collection of 48 E. faecalis strains, CRISPR-Cas systems were absent from vancomycin-resistant strains and strains associated with hospital infections and were rarely present in MDR strains (17). This suggests that CRISPR-Cas defense systems act as barriers to antibiotic resistance gene dissemination in E. faecalis.

Another genome defense mechanism utilized by bacteria, restriction-modification (R-M), functions like an innate immune system. In a simple model of R-M defense, host DNA is modified by a DNA methyltransferase (MTase) at adenine (A) or cytosine (C) residues within a specific motif sequence. A cognate restriction endonuclease (REase) cleaves motif sequences lacking appropriate modification. By this mechanism, the REase recognizes and cleaves nonself DNA attempting to enter the cell. Several broad classes of R-M systems are known (types I to III), with type II systems being most similar to the R-M model described above (19). Type IV REases recognize and cleave methylated motif sequences and do not have cognate MTases (20). Common genome modifications in the prokaryotic world are 6-methyladenine (m6A), 4-methylcytosine (m4C), and 5-methylcytosine (m5C) (21). DNA MTases do not always have cognate REases, and in those cases they are referred to as orphan MTases.

We are interested in barriers to horizontal gene transfer (HGT) in the enterococci and to what extent enterococcal cells have identity, i.e., if and how they distinguish their own genetic material from nonself genetic material during HGT. The dynamic between E. faecalis cells and the narrow-host-range pheromone-responsive plasmids is particularly of interest. Very few studies have experimentally characterized enterococcal R-M enzymes (22–26), and their roles in modulating HGT have not been assessed. However, the New England BioLabs (NEB) Restriction Enzyme Database (REBASE) predicts many R-M enzymes for the genus (27). Here, we used Pacific Biosciences single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing and Illumina bisulfite sequencing to map genome modification sites in E. faecalis OG1RF. We also evaluated the effect of differential genome modification on electrotransformability of OG1RF and conjugative transfer of the model pheromone-responsive plasmid, pCF10. We conclude that differential genome modification has the potential to impact HGT frequencies and the population structure of E. faecalis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and routine molecular biology procedures.

Bacterial strains used in this study are shown in Table 1. E. faecalis strains were routinely cultured in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth or on BHI agar at 37°C unless otherwise stated. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations for E. faecalis: rifampin, 50 μg/ml; fusidic acid, 25 μg/ml; erythromycin, 50 μg/ml; tetracycline, 10 μg/ml; streptomycin, 500 μg/ml; spectinomycin, 250 μg/ml for OG1RF and OG1SSp and 750 μg/ml for V583; chloramphenicol, 15 μg/ml. Escherichia coli strains were used as hosts for plasmid construction and were grown in lysogeny broth at 37°C unless otherwise stated. Antibiotics for E. coli were used at the following concentrations: kanamycin, 30 μg/ml; ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 15 μg/ml; spectinomycin, 100 μg/ml. PCR was routinely performed with Taq polymerase (NEB). Phusion polymerase (Fisher) was used for cloning applications. Primers used in this study are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Routine DNA sequencing was performed by Macrogen (Rockville, MD) or by the Massachusetts General Hospital DNA Core Facility (Boston, MA). REase digestions were performed per the manufacturer's instructions (NEB). Methylation sensitivity data for REases were obtained from the NEB REBASE database. Genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated from E. faecalis overnight cultures in stationary phase by using a modified version of a previously published protocol (28), described further in the supplemental material. Whole-genome amplified (WGA) control gDNA was generated by amplification of native gDNA using the Qiagen REPLI-g kit, per the manufacturer's instructions.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. faecalis strains | ||

| OG1RF (*)a | Rifampin- and fusidic acid-resistant derivative of human oral cavity isolate OG1 | 8 |

| OG1SSp (*) | Spectinomycin- and streptomycin-resistant derivative of human oral cavity isolate OG1 | 8 |

| OG1RF ΔEfaRFI | OG1RF EfaRFI (OG1RF_11622-11621) deletion mutant | This study |

| OG1RF ΔEfaRFI pAT28 | OG1RF ΔEfaRFI containing shuttle vector pAT28 | This study |

| OG1RF ΔEfaRFI pM.EfaRFI (*) | OG1RF ΔEfaRFI containing pM.EfaRFI | This study |

| OG1RF ΔEfaRFI::EfaRFIrbs | OG1RF ΔEfaRFI with chromosomal integration of OG1RF_11622-11621 between ORFs OG1RF_11778 and OG1RF_11779 | This study |

| OG1RF ΔEfaRFI::EfaRFIpro (*) | ΔEfaRFI::EfaRFIrbs with putative OG1RF_11622 promoter knocked in to OG1RF_11622-11621 integration | This study |

| V583 | Vancomycin-resistant clinical isolate | 9 |

| V583 pM.EfaRFI (*) | V583 containing pM.EfaRFI | This study |

| T11 (*) | Urinary tract infection isolate | 75 |

| CH188 | Liver abscess isolate | 76 |

| E. coli strains | ||

| EC1000 | Cloning host, providing repA in trans | 77 |

| TOP10 | Cloning host | Invitrogen |

| StbL4 | Cloning host | Life Technologies |

| BW25113 | Keio Collection host | 31 |

| JW1944 | Keio Collection dcm mutant | 31 |

| BL21(DE3) | Expression host strain | Novagen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pAT28 | Shuttle vector for E. faecalis; confers spectinomycin resistance | 35 |

| pLT06 | Markerless exchange plasmid; confers chloramphenicol resistance | 33 |

| pGEX-6p-1 | E. coli expression vector | GE Healthcare |

| pET28a | E. coli expression vector | Novagen |

| pCF10 | cCF10-inducible conjugative plasmid | 37 |

| pWH01 | pLT06 containing 2,306-bp XbaI/PstI-digested fragment of OG1RF_11621-2 | This study |

| pWH03 | pLT06 containing 1,998 XbaI/PstI-digested fragment of EF2238-NotI-EF2239 | This study |

| pWH02 | pLT06 containing 1,989-bp BamHI/PstI-digested fragment of EF2239 and OG1RF_11622 with its upstream intergenic region | This study |

| pWH21 | pGEX-6p-1 containing 1,275-bp BamHI/NotI-digested fragment of OG1RF_11823 | This study |

| pWH51 | pET28a containing 1,005-bp NdeI/BamHI-digested fragment of OG1RF_10790 | This study |

| pM.EfaRFI | pAT28 containing 1,543-bp BamHI/EcoRI-digested OG1RF_11622 with its promoter | This study |

| pCom02 | pWH03 containing 2,129-bp NotI-digested fragment of OG1RF_11621-2 with putative OG1RF_11622 ribosome binding site | This study |

Strain names followed by (*) are resistant to ApeKI and TseI digestion (Fig. 4). All E. faecalis strains were tested for ApeKI and TseI sensitivity.

Expression of predicted MTases in E. coli BL21(DE3).

The OG1RF_10790 gene was amplified using primer set 10790_for_NdeI/10790_rev_BamHI. The 1,027-bp fragment was digested with NdeI/BamHI and ligated into pET28a (Novagen), generating pWH51. The OG1RF_11823 gene was amplified using primer set 11823_for_BamHI/11823_rev_NotI. The 1,300-bp fragment was digested with BamHI/NotI and ligated into pGEX-6p-1 (GE Healthcare), generating pWH21. For overexpression of OG1RF_10790, E. coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen) transformed with pWH51 was induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and incubated at 37°C overnight with shaking at 180 rpm. E. coli BL21(DE3) transformed with wild-type pET28a was induced under the same conditions as a control. For overexpression of OG1RF_11823, E. coli BL21(DE3) transformed with pWH21 was induced with 1 mM IPTG and incubated at 25°C overnight with shaking at 180 rpm. After induction of cultures, 30 μl crude cell lysate was prepared and analyzed via 12% bis-acrylamide (Bio-Rad) SDS-PAGE and Western blotting to confirm MTase overexpression (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). For Western blotting of control pET28a and OG1RF_10790 expression strains, a mouse anti-polyhistidine antibody was used (Cell Signaling). For the OG1RF_11823 expression strain, a rabbit anti-glutathione S-transferase antibody was used (Thermo Scientific). Genomic DNA was isolated from induced cultures using the protocol described in the text in the supplemental material.

Pacific Biosciences SMRT sequencing.

SMRT sequencing of native and WGA E. faecalis OG1RF gDNA was performed at the University of California San Diego BIOGEM core facility. SMRT sequencing reads were assembled to the E. faecalis OG1RF reference sequence (GenBank accession number NC_017316) and analyzed using the RS modification and motif detection protocol in SMRT portal v1.3.3. SMRT sequencing of E. coli BL21(DE3) gDNA after overexpression of predicted MTases was performed at the University of Michigan sequencing core facility. SMRT sequencing reads were assembled to the E. coli BL21(DE3) reference sequence (GenBank accession number CP001509.3) and analyzed using the RS modification and motif detection protocol in SMRT portal v2.3.0. The interpulse duration (IPD) is the time elapsed between incorporation of adjacent nucleotides by DNA polymerase, and the IPD ratio refers to the ratio of IPD values between native and control templates for a given nucleotide position. The significance of the IPD ratio was evaluated using Welch's t test, with the resulting P value further transformed into a quality value (QV; QV = −log10 P; details can be found by accessing PacificBiosciences/kineticsTools on github, the Web-based Git repository hosting service). SMRT sequencing analysis is described further in the supplemental material. Additional analyses of motif enrichment were performed with MEME (29).

Targeted bisulfite sequencing.

Methylated DNA was generated by PCR using E. faecalis OG1RF gDNA as the template, primers targeting clpX, and m5CTP, m4CTP, or CTP (Fermentas) as nucleotide substrates. PCR products were bisulfite converted by using the EpiTect bisulfite kit (Qiagen) per the manufacturer's instructions, reamplified by PCR with dCTP, and sequenced. To evaluate modification at 5′-GCWGC-3′ motifs, OG1RF gDNA was bisulfite converted as described above and used as the template in standard PCRs with primers targeting bisulfite-converted OG1RF_11844 sequence. Products were sequenced to evaluate the methylation state of the two OG1RF_11844 5′-GCWGC-3′ motifs. To evaluate modification at 5′-CCGG-3′ motifs in E. coli BL21(DE3) expressing OG1RF_11823, E. coli gDNA was bisulfite converted as described above and used as the template in standard PCRs with primers targeting bisulfite-converted ECD_00002 sequence (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Primers targeting bisulfite-converted DNA were designed using MethPrimer (30).

Illumina MiSeq whole-genome bisulfite sequencing.

Bisulfite-converted Illumina sequencing libraries were constructed using the Illumina TruSeq sample prep (LT) kit and the Qiagen EpiTect bisulfite kit, described further in the supplemental material. E. coli strains BW25113 and JW1944 (dcm deficient) (31) were used as positive and negative controls for bisulfite conversion, based on the well-characterized Dcm methylation system. OG1RF WGA control DNA was also used as negative control. Illumina sequence reads were mapped to the OG1RF reference sequence or the E. coli K-12 MG1655 reference sequence (GenBank accession number NC_000913) by using Bismark (32) with paired-end read mapping. The bisulfite conversion rate for individual reads was calculated by dividing the number of C-to-T conversions in each mapped read by the total number of Cs in the corresponding reference sequence. For determination of methylation ratios, only reads with a ≥80% bisulfite conversion rate were used. A sequencing depth threshold of ≥7 was further applied to reduce bias generated by low coverage. The methylation ratio for each C position in the reference genome was calculated by dividing the number of mapped Cs by the total coverage at that position. The significance of the methylation ratio was calculated using empirical modeling, with OG1RF WGA or dcm-deficient DNA as the background (negative control) (described further in the supplemental material).

Generation of an E. faecalis ΔEfaRFI mutant.

Approximate 1-kb regions up- and downstream of OG1RF_11622-11621 were amplified using primer sets 1F_BamHI/1R_XbaI and 2F_PstI/2R_BamHI (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Products were digested with REases and ligated with Xbal/PstI-digested pLT06 (33) by using T4 DNA ligase (NEB). The ligation product was transformed into E. coli EC1000 for propagation and sequence confirmation. The deletion construct, pWH01, was introduced into OG1RF by electroporation (34). The OG1RF ΔEfaRFI strain lacking OG1RF_11622-11621 was generated by temperature shifts and p-chlorophenylalanine counterselection, as previously described (33). Deletion of OG1RF_11622-11621 was confirmed by sequencing of the engineered region.

OG1RF ΔEfaRFI complementation.

In one complementation strategy, OG1RF_11622 was provided in trans on the multicopy shuttle vector pAT28 (35). OG1RF_11622 with 386 bp of upstream sequence was amplified using the primer set M1_F_EcoRI/M1_R_BamHI. Products were digested with REases, ligated with EcoRI/BamHI-digested pAT28, and transformed into E. coli Top10 (Invitrogen) for propagation and sequence confirmation. The complementation construct, pM.EfaRFI, was introduced into OG1RF ΔEfaRFI by electroporation to generate the strain OG1RF ΔEfaRFI pM.EfaRFI and into V583 to generate the strain V583 pM.EfaRFI.

In a second complementation strategy, the OG1RF_11622-11621 genes were incorporated into the OG1RF ΔEfaRFI chromosome at a neutral site. An E. faecalis genomic insertion site for expression (GISE) was previously identified (36). This site occurs in the intergenic region between the V583 genes EF2238 and EF2239, which are orthologues of OG1RF_11778 and OG1RF_11779. We refer to these genes by their V583 ORF IDs here. Debroy et al. (36) developed pRV1, a plasmid conferring erythromycin resistance that can be used to knock in genes at the E. faecalis GISE. We used this information to develop pWH03, a pLT06 derivative conferring chloramphenicol resistance that can be used for gene knock-ins at the GISE. To generate pWH03, EF2238 and EF2239 orthologues were amplified from OG1RF gDNA using previously published primer sets with modified restriction sites (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) (36). Overlap extension PCR using the first-round products and primers EF2238_F_PstI/EF2239_R_XbaI introduced a NotI site between the two genes, resulting in a PstI-EF2238-NotI-EF2239-XbaI fragment. The REase-digested fragment was ligated into PstI/XbaI-digested pLT06 and propagated in E. coli EC1000, generating pWH03.

To complement the OG1RF ΔEfaRFI mutant, the OG1RF_11622-11621 genes with 33 bp of upstream sequence were amplified using the primer set RBS_R_NotI/ORF_F_NotI. The NotI-digested fragment and NotI-digested pWH03 were ligated and electroporated into E. coli StbL4 competent cells (Life Technologies), generating pCom02. pCom02 was electroporated into OG1RF ΔEfaRFI, and temperature shifts and counterselection were used to generate the strain OG1RF ΔEfaRFI::EfaRFIrbs. The promoter region upstream of OG1RF_11622-11621 was separately knocked into OG1RF ΔEfaRFI::EfaRFIrbs. Sequence 331 bp upstream of OG1RF_11622 and 775 bp of the OG1RF_11622 coding region were amplified using the primer pair M2_1F_PstI/M2_1R. A second round of PCR combined this PCR product with an EF2239 PCR product, generating a PstI-OG1RF_11622-promoter-EF2239-BamHI fragment. This was digested with PstI/BamHI, ligated to PstI/BamHI-digested pLT06, and transformed into E. coli EC1000 for propagation, resulting in pWH02. The construct was electroporated into OG1RF ΔEfaRFI::EfaRFIrbs, and temperature shifts and counterselection were used to obtain OG1RF ΔEfaRFI::EfaRFIpro.

RT-qPCR.

Exponentially growing E. faecalis broth cultures were diluted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.005 in prewarmed BHI broth, and growth was monitored by spectrophotometry. At four time points (when OD600 values were 0.05, 0.35, 1.0, and 2 to 2.2), cultures were harvested with two volumes RNAProtect bacteria reagent (Qiagen). RNA was isolated from cell pellets by using RNA Bee reagent (Tel-Test), treated with DNase I (Roche) for 2 h at 37°C, and repurified using RNA Bee. The absence of gDNA contamination was confirmed by PCR using 1 μg of RNA as the template and primers targeting a 16S rRNA gene (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). RNA integrity was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis. cDNA was generated using SuperScript II (Life Technologies) with 100 ng RNA template and random hexamers. RNase H (NEB) was added to synthesized cDNA to remove RNA, and cDNA was purified with the Qiaquick PCR purification kit. Primers for reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) were designed using NCBI Primer-BLAST (34). RT-qPCR was carried out using a Cepheid Smart Cycler with SYBR green I (Sigma). Threshold cycle (CT) values for clpX reactions were compared to those for MTase reactions. Expression levels were analyzed for two independent growth experiments.

Conjugation frequency test.

The pheromone-responsive plasmid pCF10 (37), which carries genes for tetracycline resistance, was used for conjugation frequency tests. Donor and recipient strains were inoculated into BHI broth from single colonies and grown to late exponential phase. An aliquot (900 μl) of the recipient culture was pelleted and resuspended with 100 μl of donor culture. The mixture was spread on a BHI plate and incubated at 37°C overnight. Bacterial growth was recovered with 1× phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with 2 mM EDTA. Cell resuspensions were serially diluted and plated on selective media. Select transconjugants were verified by colony PCR using two sets of primers designed from the pCF10 sequence (38), with one set targeting Tn916 and one set targeting the uvaB gene (data not shown). Transfer efficiency was expressed as the number of pCF10 transconjugants per donor (39). Significance was assessed using the paired t test.

Transformation efficiency test.

Electrocompetent E. faecalis cells were made as described previously (40). The test plasmid pMSP3535 (41) was introduced into either OG1RF or OG1RFΔEfaRFI for propagation and purified using cesium chloride density gradient centrifugation (42). The control plasmid pLZ12 (43) was propagated in E. coli DH5α and purified by use of a column miniprep (Qiagen). During electroporation, 50 ng of pMSP3535 with varied modification status was coelectroporated with 50 ng of pLZ12 into OG1RF competent cells. Electroporation reaction mixtures were divided into equal volumes and plated on appropriate selection media (with chloramphenicol for pLZ12 and erythromycin for pMSP3535) after 1.5 h of outgrowth. The efficiency of transformation (EOT) in this study was defined as the relative number of transformants obtained from the test plasmid versus that from the control plasmid (based on methods described in reference 44). The EOT should not be confused with the conventional definition of transformation efficiency, with which the number of transformants per microgram of DNA is calculated. The EOT from modified pMSP3535 was set to 1, and the EOT from unmodified pMSP3535 was expressed in relation to that. By doing this, we normalized for total transformable cells by using the control plasmid, allowing us to assess the impact of modification status on transformability of the test plasmid. Three independent experiments were performed, and significance was assessed using a paired t test.

Putative DNA MTases in E. faecalis OG1RF and their distributions among 17 E. faecalis strains.

Three DNA MTases are predicted for OG1RF by the NEB REBASE (Table 2). For comparative analysis with V583, genes flanking OG1RF DNA MTase candidates were queried against the V583 genome by using BLASTn until sequence identity was found. Regions of interest in the OG1RF and V583 genomes were aligned using Geneious (Biomatters, Ltd.). To assess the distribution of DNA MTases among a collection of 17 previously sequenced E. faecalis genomes (12, 13), each MTase protein sequence was pairwise aligned against all predicted protein sequences from the 17 E. faecalis strains.

TABLE 2.

Predicted DNA MTases in E. faecalis OG1RF

| MTase name | Locus ID | Annotationb | Function predicted by REBASE | Pfam hitc | REased |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M.EfaRFI | OG1RF_11622 | bbviM DNA cytosine-5 MTase | Putative type II cytosine-5 DNA MTase, probably recognizes GCSGC | DNA methylase (1.8e−73) | R.EfaRFI (Pfam hit: RE_NgoFVII) |

| M.EfaRFII | OG1RF_11823 | MTase | Putative type II N4-cytosine or N6-adenine DNA MTase, probably recognizes CCWGG | Methyltransf_26 (2.7e−11) | R.EfaRFII (Pfam hit: HATPase_c_3) |

| M.EfaRFORF10790Pa | OG1RF_10790 | hpaIIM DNA cytosine-5 MTase | Putative type II cytosine-5 DNA MTase, unknown recognition sequence | DNA methylase (2.0e−87) |

This nomenclature is used in REBASE for putative R-M enzymes.

From the NCBI Gene database.

The expectation value is shown in parentheses.

Potential REases were predicted using REBASE.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Data from the Illumina and SMRT sequence reads generated in this study have been deposited into the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under BioProject record number SRP055177.

RESULTS

Putative DNA MTases in E. faecalis OG1RF.

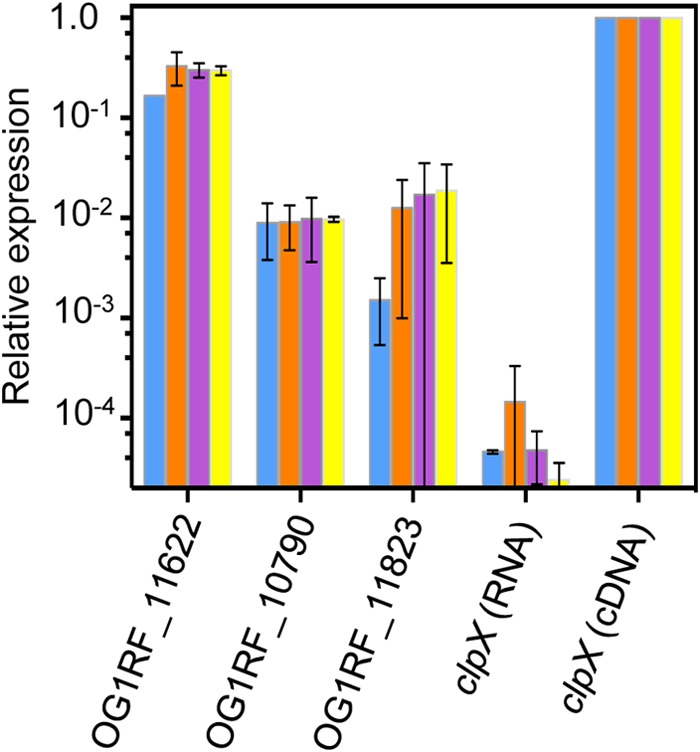

The NEB REBASE (27) predicts 3 DNA MTases for E. faecalis OG1RF (Table 2). To determine whether the putative DNA MTase genes are transcriptionally active, RNA was harvested at four points across the growth curve of OG1RF laboratory cultures. RT-qPCR with primers targeting each of the predicted DNA MTase genes and the housekeeping control gene clpX was performed with cDNA templates, and expression levels of the MTase genes were compared to that of clpX. The clpX gene codes for the ATPase subunit of the housekeeping ClpXP protease (45), and its expression is unaffected by changes in E. faecalis growth rate (46). For negative controls, reactions were performed with clpX primers and RNA templates. Signal was detected for all 3 predicted DNA MTases at all time points, although expression levels relative to clpX varied (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Transcriptional activity of candidate DNA MTases in OG1RF. cDNA was used as the template for RT-qPCR with primers targeting predicted DNA MTases and the control gene, clpX. Expression values were quantified relative to clpX. Negative control reactions were performed with RNA template and clpX primers. Blue bar, OD600 = 0.05; orange bar, OD600 = 0.35; purple bar, OD600 = 1.0; yellow bar, OD600 = 2 to 2.2. Bars represent averages of two independent growth curve experiments, with standard deviations shown.

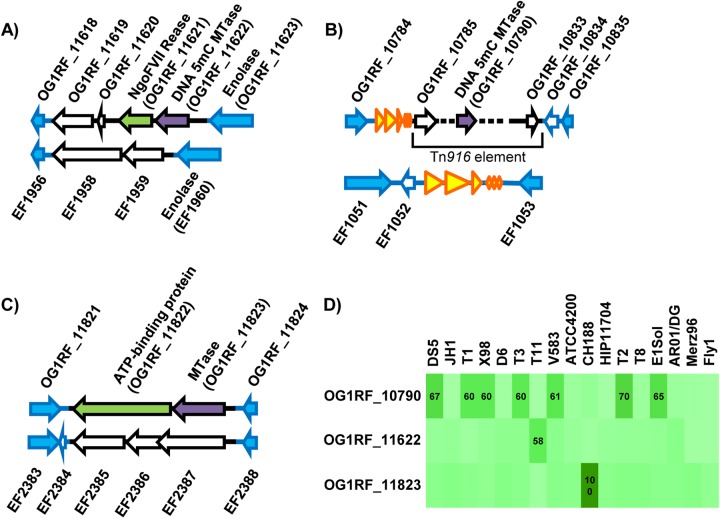

Genomic analysis and conservation of predicted DNA MTases.

We examined the genetic context of the predicted OG1RF DNA MTases relative to E. faecalis V583 (Fig. 2). OG1RF_11622-OG1RF_11619 are encoded between orthologues of the V583 genes EF1960 and EF1956; each of the two strains possess strain-specific genes between those loci (Fig. 2A). OG1RF_11621 is likely cotranscribed with OG1RF_11622 (17-bp intergenic region) and encodes a putative NgoFVII family REase (Pfam family RE_NgoFVII; E value of 3.9e−53) (Table 2). The R-M genes are flanked by 103-bp direct repeat sequences, only one copy of which is present in V583.

FIG 2.

Distributions of OG1RF DNA MTases in previously sequenced E. faecalis strains. (A to C) Analysis of synteny with E. faecalis V583. Genes shared with V583 are shown in blue. Genes with blue outlines and a white interior indicate V583 genes whose sequence is present in OG1RF but not annotated. Genes with black outlines are strain specific. DNA MTases are colored purple, and putative REases are green. Yellow arrows are rRNA and tRNA genes. (A) OG1RF_11622 region; (B) OG1RF_10790 region; (C) OG1RF_11823 region. (D) Occurrence of predicted OG1RF MTases in 17 previously sequenced E. faecalis strains. Pairwise alignments between each predicted OG1RF MTase and the entire protein complement from each of the other strains were performed using ClustalW. The intensity of the green shading indicates the percent amino acid sequence identity between query sequences and best hits, with darker green indicating greater sequence identity. The numbers shown are the percent amino acid sequence identity for best pairwise hits. Only values of ≥50% are shown.

OG1RF_10790 is encoded within a 48.9-kb Tn916-like element inserted downstream of an rRNA-tRNA gene cluster occurring between orthologues of the V583 genes EF1051 and EF1053 (Fig. 2B). Other genes with putative R-M functions are present near OG1RF_10790, including OG1RF_10794, encoding a putative ArdA type I R-M antirestriction protein (Pfam family ArdA; E value, 2.3e−45), and OG1RF_10795, encoding a possible type IV REase (Pfam family Mrr_cat; E value, 2.9e−5). OG1RF_10790 appears to be an orphan MTase, although this is difficult to state conclusively based on sequence analysis alone. The protein sequence of OG1RF_10790 has 61% identity with EF2340 from V583 (Fig. 2D), which is also predicted to be an MTase based on information in REBASE. EF2340 is encoded within a potential pathogenicity island (11), which is consistent with a mobile origin for this MTase.

OG1RF_11823-OG1RF_11822 are likely cotranscribed (2-bp intergenic region) and are present between orthologues of the V583 genes EF2383 and EF2388 (Fig. 2C). OG1RF_11822 is predicted to be an REase by REBASE (Table 2). Pfam analysis indicated that OG1RF_11822 encodes a putative histidine kinase-like, DNA gyrase B-like, and HSP90-like ATPase protein (Pfam HATPase_c_3; E value, 2.1e−28).

The distribution of the 3 predicted DNA MTases among a previously sequenced collection of 17 E. faecalis strains (12, 13) was investigated using pairwise protein sequence alignments. Figure 2D shows the percent amino acid sequence identities for best pairwise hits. Collectively, results of comparative analyses were consistent with the three predicted DNA MTases of OG1RF being horizontally acquired. Therefore, at least when using OG1RF as a reference, we were unable to identify a core R-M system for the E. faecalis species.

SMRT sequencing identified a putative m5C modification motif in OG1RF.

SMRT sequencing has been used to characterize the methylomes of bacteria (47–54). During SMRT sequencing, DNA polymerase kinetics are monitored in real time; modified bases in the sequencing template lead to altered polymerase kinetics relative to those obtained with an unmodified template (55, 56). Because DNA polymerase contacts several nucleotide positions during DNA synthesis, polymerase kinetics can be altered over a range of positions near a modified base, generating secondary kinetic signals (53, 55, 56).

We sequenced native OG1RF DNA and OG1RF WGA control DNA via SMRT sequencing. Sequence reads were aligned to the reference OG1RF genome sequence with greater than 99.99% consensus accuracy. Mean coverage depths for the native and WGA samples were 181× (range, 0 to 534×; 150 nucleotide [nt] positions with <10× coverage) and 295× (range, 0 to 825×; 102 nt positions with ≤10× coverage), respectively. Regions of zero coverage occurred in rRNA operons, presumably because of sequence redundancy in the 4 rRNA operons in E. faecalis OG1RF. Five sequence variations between our OG1RF sequence and the OG1RF GenBank reference sequence were detected in both native and WGA read alignments with >90% confidence and ≥5× coverage (see Table S2A in the supplemental material). Three of the five variations mapped to redundant rRNA genes and are unlikely to be true sequence variations. The remaining two variations are predicted nonsynonymous substitutions that occur within the OG1RF_11594 and OG1RF_10019 (manX2) coding regions. We did not analyze these variations further.

Modification motifs predicted by the SMRT portal analysis pipeline for native OG1RF gDNA are shown in Table 3. m6A and m4C modifications require modest sequencing coverage (25× per strand) for detection by SMRT sequencing; m5C modifications require high coverage (250× per strand). Based on the average fold coverage of the native sample (181×), we expected to detect m6A and m4C but not m5C modifications with high confidence. No A modification motifs were detected; however, C modification motifs containing GCNGC, GCAGC, and GCTGC and one modified G motif containing GCAGC were predicted with low detection rates (Table 3). The modified G could be a spurious prediction resulting from proximity to a GCAGC motif. These data, along with our own analysis of nucleotide positions having the most significant IPD ratios (see text in the supplemental material as well as Fig. S2 and Table S2B), indicated that a 5′-G-m5C-WGC-3′ modification occurred in OG1RF.

TABLE 3.

Modified sequence motifs in E. faecalis OG1RF and E. coli BL21(DE3) detected by the SMRT analysis pipeline

| Strain | Motifa | Total no. of motifs in genome | No. of modified motifs detected (% of total)b | Mean modification QVc | Mean motif coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. faecalis OG1RF | GCNGCAGCd | 377 | 198 (52.5) | 73.6 | 118× |

| GCTGCAANNNNNNNT | 100 | 23 (23) | 51.4 | 120× | |

| GNGCAGCT | 163 | 26 (16) | 58.3 | 119× | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3)(pET28a) | GATC | 37,562 | 37,555 (99.98) | 211.4 | 135× |

| E. coli expressing OG1RF_11823e | CCGG | 47,782 | 21,776 (45.57) | 55.3 | 83× |

| E. coli expressing OG1RF_10790e | None detected | ||||

The predicted modified position is underlined.

The percent motif detection was calculated by dividing the number of modified motifs that were detected by the total number of motifs in the genome.

Mean QV for modified bases in motifs.

Contains overlapping GCNGC motifs.

Dam modifications were removed during postprocessing of data.

Bisulfite sequencing to discriminate common prokaryotic C modifications.

Bisulfite sequencing is commonly used to detect m5C in eukaryotic DNA (57, 58), and has been used to study Dcm methylation (5′-C-m5C-WGG-3′, where underlining indicates the modified position) in E. coli (59). Unmodified Cs are susceptible to deamination by bisulfite, and through a series of chemical treatments, Cs in a DNA template are converted to uracils while m5Cs are protected. Sequencing of bisulfite-converted gDNA reveals protected (C) versus unprotected (T) sites in the DNA template (60).

One potential issue with applying bisulfite sequencing to prokaryotic genomes is discrimination between m5C and m4C. A previous study used small-scale bisulfite sequencing to attempt to distinguish between m5C- and m4C-modified templates, and the researchers found that m5C sites are fully protected from bisulfite conversion while m4C sites are sometimes protected (61). We confirmed these results through independent experimentation. We used dm4CTP, dm5CTP, and dCTP as nucleotide substrates for PCRs targeting the OG1RF clpX gene, bisulfite converted the PCR products, and then amplified and sequenced the bisulfite-converted DNA. dCTP products were fully bisulfite converted, dm5CTP products were fully protected, and dm4CTP products were partially protected (as evidenced by C/T mixed peaks in sequencing chromatograms [see Fig. S3A in the supplemental material]). Partial protection of dm4CTP products was reproducible over 2 independent trials. Alteration of bisulfite conversion reaction conditions may result in complete conversion of m4C, although we did not test this.

We used a similar approach to assess the methylation state of two 5′-GCWGC-3′ motifs occurring within the gene OG1RF_11844. OG1RF gDNA was bisulfite converted, and an internal region of OG1RF_11844 was amplified by PCR and sequenced. Sequencing chromatograms revealed complete bisulfite conversion of all C positions except for the underlined position in the 5′-GCWGC-3′ motifs (see Fig. S3B in the supplemental material). The full protection of these positions from bisulfite conversion suggests that 5′-GCWGC-3′ motifs are modified with m5C in OG1RF.

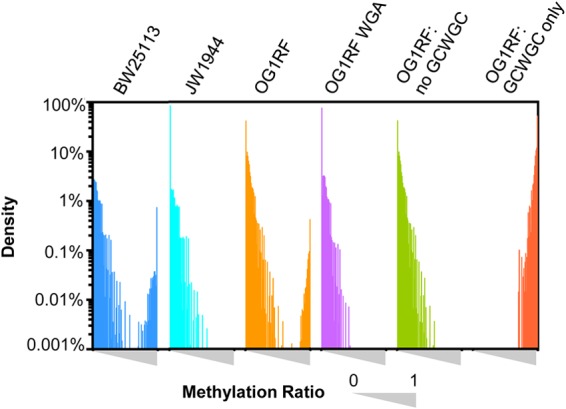

Bisulfite sequencing confirmed 5′-GCWGC-3′ modification in OG1RF.

We used bisulfite sequencing to explore the extent of m5C modification in the OG1RF genome, with OG1RF WGA DNA and E. coli dcm+ and dcm-deficient strains serving as controls. Illumina reads were mapped to reference sequences, and reads were filtered based on bisulfite conversion ratios as described in the supplemental material (see also Table S2C and D and Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Methylation ratios for each C position with a coverage of ≥7× were calculated using the filtered read assemblies. The methylation ratio was calculated by dividing the number of Cs that mapped to a given position by the total coverage at that position. By this calculation, a bisulfite-protected, m5C position would have a methylation ratio value near 1, a partially protected m4C position would have a methylation ratio near 0.5, and unmethylated C positions would have values near 0. Coverage depths and mean methylation ratios calculated for the read assemblies are shown in Table S2C in the supplemental material. Figure 3 compares the distribution of methylation ratios in native OG1RF gDNA and its WGA control. While most of the C positions have low methylation ratios, some C positions have methylation ratios near 1 in native OG1RF, consistent with protection from bisulfite conversion by m5C modification. When examining Cs with high methylation ratios, 5′-GCWGC-3′ motifs are enriched, with the underlined cytosine bisulfite protected. The density plots of methylation ratios were compared between 5′-GCWGC-3′ motifs and all other C positions (Fig. 3). Of the 5′-GCWGC-3′ motifs in the OG1RF genome 83% were bisulfite protected, with the remaining 17% of the motifs not adequately covered by sequence reads (see Table S2D in the supplemental material).

FIG 3.

Distribution of methylation ratios for C positions in bisulfite sequencing assemblies. The distributions of methylation ratios for E. coli BW25113 (dcm+), E. coli JW1944 (dcm-deficient), and E. faecalis OG1RF native and WGA DNA are shown. Within each interval, the methylation ratio of each sample ranged from 0 to 1 (left to right). For OG1RF native gDNA, cytosine positions within the GCWGC motif have methylation ratios near 1 (OG1RF: GCWGC only). If GCWGC motifs are removed from the analysis (OG1RF: no GCWGC), the methylation ratio distribution is similar to that of OG1RF WGA DNA. The y axis represents the density percentage (percentage of total nucleotide positions) on a logarithmic scale.

The detection rate for 5′-GCWGC-3′ modification in OG1RF was compared between SMRT and bisulfite sequencing (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). The detection event was defined as a QV of >40. In bisulfite sequencing, the detection rate is 83.3%; however, this number is likely artificially low due to reduced sequencing coverage in bisulfite-converted read assemblies. For positions meeting our coverage threshold, the detection rate was 100% (see Table S3). Conversely, SMRT sequencing achieved a coverage of >99% for 5′-GCWGC-3′ motifs in the OG1RF genome, but the detection rate for 5′-GCWGC-3′ modifications was only 5.1%. Therefore, in our studies bisulfite sequencing was superior to SMRT sequencing for the detection of m5C modifications.

OG1RF_11622 modifies 5′-GCWGC-3′ motifs in the OG1RF genome.

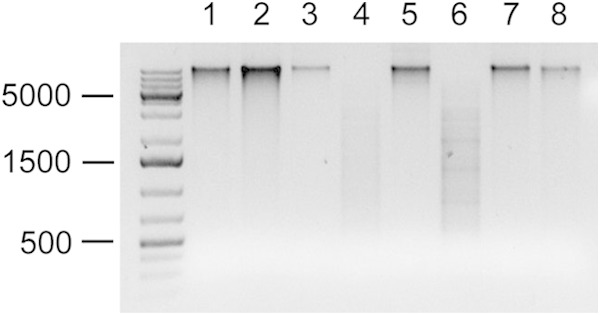

ApeKI and TseI are commercially available REases that recognize 5′-GCWGC-3′ motifs and whose activities are blocked by m5C modification at the underlined position. ApeKI and TseI digested OG1RF WGA DNA (data not shown), while OG1RF native DNA was protected from these enzymes (Fig. 4). We interpret this findings to mean that ApeKI and TseI are also blocked by modification at the internal C position of the 5′-GCWGC-3′ motif. Interestingly, gDNA from E. faecalis T11, a strain that encodes a protein with 58% sequence identity to OG1RF_11622 (Fig. 2D), was also protected from ApeKI and TseI digestion (Table 1).

FIG 4.

OG1RF_11622 (M.EfaRFI) is responsible for 5′-GCWGC-3′ methylation. gDNAs from OG1RF (lanes 1 and 2 for undigested control and digested sample, respectively), OG1RF ΔEfaRFI (lanes 3 and 4), OG1RF ΔEfaRFI pAT28 (lanes 5 and 6), and OG1RF ΔEfaRFI pM.EfaRFI (lanes 7 and 8) were digested with ApeKI. gDNA (600 ng) was digested in a 50-μl reaction volume, and 10-μl samples were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA size standards are shown on the left. TseI digestions yielded identical results (data not shown).

To identify the MTase responsible for 5′-GCWGC-3′ methylation, we deleted the OG1RF_11621 and OG1RF_11622 genes. OG1RF_11622 was chosen because of its high sequence identity with M.BceSIV, a Bacillus cereus DNA MTase that is thought to modify 5′-GCAGC-3′ motifs with m5C (47). OG1RF_11621 was deleted along with OG1RF_11622, under the assumption that OG1RF_11621 encodes an REase that would be toxic to the cell in the absence of its cognate MTase. Protection of 5′-GCWGC-3′ motifs was lost in the OG1RF_11621-2 deletion mutant, and trans complementation with the multicopy vector pAT28 expressing OG1RF_11622 rescued gDNA from digestion (Fig. 4). E. faecalis V583 lacks an OG1RF_11622 orthologue (Fig. 2D), and V583 gDNA is susceptible to cleavage by ApeI and TseI (Table 1). Expression of the OG1RF_11622 MTase in V583 protects V583 gDNA from digestion (Table 1). Collectively, these results demonstrate that OG1RF_11622 is a DNA MTase that modifies 5′-GCWGC-3′ motifs. We have named this system EfaRFI in accordance with nomenclature rules (62).

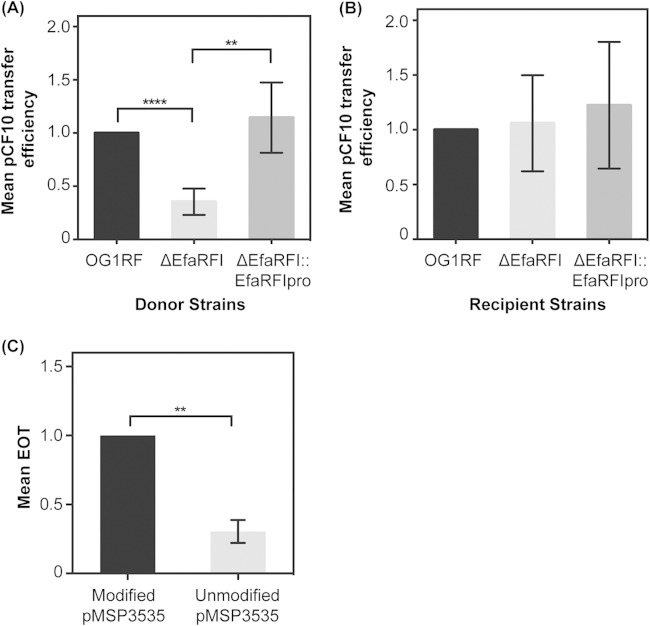

Differential genome modification affects plasmid transfer frequency in E. faecalis.

5′-GCWGC-3′ modification in OG1RF could affect plasmid transfer efficiency and antibiotic resistance gene dissemination. Transfer of the model pheromone response plasmid pCF10, which carries genes for tetracycline resistance and possesses 59 5′-GCWGC-3′ REase recognition motifs, was assessed (37). We used OG1RF and derivative strains as plasmid donors in conjugation reactions with OG1SSp as the recipient. Note that OG1RF and OG1SSp are derivatives of the same parent strain, and like OG1RF, OG1SSp gDNA is protected from ApeKI digestion (Table 1). In this experimental design, modification of pCF10 at 5′-GCWGC-3′ motifs varies with the host strain: pCF10 in OG1RF and OG1SSp is modified similarly at 5′-GCWGC-3′ motifs, while pCF10 in the ΔEfaRFI mutant lacks 5′-GCWGC-3′ modification. Our expectation was that pCF10 lacking 5′-GCWGC-3′ modification would be restricted by OG1SSp, resulting in a lower DNA transfer efficiency from the ΔEfaRFI mutant to OG1SSp. As expected, the pCF10 transfer frequency from the ΔEfaRFI mutant was significantly lower than from the wild type, OG1RF (P = 8e−7) (Fig. 5A). To assess the transfer frequency from a complemented mutant strain, the EfaRFI R-M genes under the control of their native promoter were incorporated into the ΔEfaRFI mutant chromosome at a neutral site (the previously described E. faecalis genomic insertion site for expression [36]). With this strategy, antibiotic selection was not required to maintain the complementation construct during conjugation experiments. The plasmid transfer frequency from the complemented strain ΔEfaRFI::EfaRFIpro to OG1SSp was similar to that observed for the wild type, OG1RF (Fig. 5A). For the reverse experiment, with OG1SSp as donor and the OG1RF strains as recipients, the R-M system should not be a barrier to conjugation. As expected, we observed similar conjugation frequencies for OG1RF and its derivative recipient strains (Fig. 5B).

FIG 5.

Genome modification impacts plasmid transfer efficiency and electrotransformability. (A) OG1RF wild type, the ΔEfaRFI mutant, and the ΔEfaRFI::EfaRFIpro-complemented strain were used as pCF10 donors in conjugation reactions with OG1SSp as the recipient. In this experimental design, the modification status of pCF10 at 5′-GCWGC-3′ motifs varied. For each trial, the pCF10 transfer efficiency (pCF10 transconjugants/donor) from OG1RF to OG1SSp was set to 1. Transfer efficiencies for the other donor strains were expressed relative to this rate. Bars represent mean values, and standard deviations are shown (n = 8 trials for OG1RF and ΔEfaRFI and n = 5 trials for ΔEfaRFI::EfaRFIpro). Significance was assessed by paired t test. (B) Conjugation frequency assessed as described for panel A, but with donor and recipient strains reversed. For these experiments, OG1SSp donated modified pCF10 to OG1RF and its derivatives. The transfer efficiency from OG1SSp to OG1RF was set to 1. Transfer efficiencies for the other recipient strains were expressed relative to this rate. Three independent experiments were performed. (C) EOT assay results. The EOT from modified pMSP3535 was set to 1. The EOT from unmodified pMSP3535 was significantly lower over three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001.

Differential genome modification affects electrotransformability of E. faecalis OG1RF.

The EfaRFI R-M system in OG1RF could affect the plasmid transformation efficiency. E. faecalis OG1RF possesses competence genes (10), but natural transformation has not been demonstrated. We therefore tested transformation efficiency via electroporation. The plasmid pMSP3535, containing 12 5′-GCWGC-3′ REase recognition motifs, was modified by M.EfaRFI when propagated in OG1RF (data not shown); pMSP3535 was propagated in OG1RF ΔEfaRFI to obtain unmodified plasmid. The control plasmid pLZ12, propagated in E. coli DH5α, was used to normalize the total number of transformable cells. The EOT was calculated for three independent experiments as described in Materials and Methods. When comparing the EOT of 5′-GCWGC-3′-modified pMSP3535 to that of unmodified pMSP3535, we observed that unmodified pMSP3535 had a statistically significantly lower EOT than modified pMSP3535 when electroporated into OG1RF (Fig. 5C).

Expression of OG1RF_11823 and OG1RF_10790 in E. coli.

Having determined that the EfaRFI system is an active R-M system in OG1RF, we turned our attention to the other two REBASE-predicted DNA MTases for OG1RF. Our qRT-PCR analysis showed low transcriptional activities of these genes in OG1RF under laboratory growth conditions (Fig. 1). To determine whether the two genes encode DNA MTase activities, we expressed the genes in the heterologous host E. coli BL21(DE3), using an IPTG-inducible promoter to control expression. E. coli BL21(DE3), E. coli BL21(DE3) expressing OG1RF_11823, and E. coli BL21(DE3) expressing OG1RF_10790 were analyzed by SMRT sequencing. An expanded analysis of these data is detailed in the text in the supplemental material. Sequence reads from all three samples were aligned to the BL21(DE3) reference genome with greater than 99.99% consensus accuracy. Mean coverage depths were 277×, 86×, and 164× for the three strains, respectively. Modification motifs predicted by the SMRT portal are listed in Table 3. For E. coli BL21(DE3) carrying the pET28a plasmid, 5′-G-m6A-TC-3′ was detected. This was expected, as this E. coli strain is dam+. We used this strain as a reference control to determine whether genome modification occurred in the two OG1RF MTase-expressing strains. A cytosine modification motif, 5′-CCGG-3′, was detected in the strain expressing OG1RF_11823; no modification was detected in the strain expressing OG1RF_10790 (Table 3). Considering the mean coverage depth for the strain expressing OG1RF_10790 (164×), we cannot fully exclude the presence of an m5C modification, which requires 250× coverage depth.

To confirm that 5′-CCGG-3′ methylation occurs in E. coli expressing OG1RF_11823, we used the methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme HpaII, which recognizes 5′-CCGG-3′ but is blocked by cytosine methylation. While gDNA extracted from an uninduced (no-IPTG) culture was fully digested by HpaII, IPTG induction of OG1RF_11823 expression protected E. coli gDNA from HpaII cleavage (data not shown).

Since targeted bisulfite sequencing can distinguish between m4C and m5C (Fig. S3A in the supplemental material), we performed targeted bisulfite sequencing to determine whether OG1RF_11823 is an m4C or an m5C MTase. The partial conversion of cytosine to thymidine within 5′-CCGG-3′ motifs was observed, supporting the existence of m4C methylation (see Fig. S3C). From these data, along with the SMRT sequencing data, we concluded that OG1RF_11823 modifies 5′-CCGG-3′ motifs with m4C. We have named this enzyme M.EfaRFII (Table 2).

OG1RF gDNA is not protected from HpaII digestion (data not shown). This is consistent with our qRT-PCR results that showed that transcriptional activity of OG1RF_11823 is low in laboratory culture. An orthologue of OG1RF_11823 is present in E. faecalis strain CH188 (Fig. 2D), and gDNA from CH188 was also fully digested by HpaII (data not shown). Expression of EfaRFII may be induced in environments other than our standard laboratory culture conditions.

DISCUSSION

Motivated by our interest in E. faecalis genome defense and horizontal gene transfer, in this study we used a combination of sequencing-based approaches to assess genome modification in the model E. faecalis strain, OG1RF. DNA modification has important functional roles in organisms across the tree of life. In prokaryotes, DNA modification allows for the discrimination of self from nonself DNA and contributes to housekeeping functions, such as chromosome replication, mismatch repair, and the regulation of gene expression (63). Despite its biological relevance, methods to assess DNA modification on a genome-wide scale have been limited, until recently. Bisulfite sequencing is commonly used for the identification of m5C sites in eukaryotic genomes (reviewed in reference 58). SMRT sequencing is a relatively recently developed method of hypothesis-independent identification of genome modification sites (55, 56). Each of these techniques has strengths and weaknesses. Analysis of bisulfite sequence data is complicated by the harshness and inconsistency of bisulfite conversion and the reduction in sequence complexity occurring as a result of bisulfite conversion, which effectively necessitates a preexisting reference genome (64). SMRT sequencing, on the other hand, combines de novo sequencing with methylation detection. It is a very effective technique for the identification of m6A and m4C sites in bacterial genomes but is less effective at identifying m5C sites. This is because only subtle changes in polymerase kinetics are generated by m5C (53, 55). Tet1 oxidation has been utilized to convert m5C to 5-carboxylcytosine, which enhances detection of m5C sites in bacterial genomes (49, 52–54). This protocol amendment was not utilized in our study.

Both SMRT and bisulfite sequencing detected modification occurring at 5′-GCWGC-3′ motifs in the E. faecalis OG1RF genome, but the efficacy of the two techniques differed. While bisulfite sequencing detected m5C with an ∼100% detection rate, SMRT sequencing required that we take secondary peaks into account. Different from the previously reported secondary peaks occurring 2 and 6 bases upstream of m5C positions (53), here we found secondary peaks 3 and 6 bases upstream of the modified position in native OG1RF gDNA (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The presence of GCWGCWGC sequences (overlapping GCWGC motifs) improved detection by SMRT sequencing (see Table S2B in the supplemental material). Note that the default SMRT pipeline identified a modified G motif (Table 3), a spurious prediction resulting from kinetic signals secondary to m5C. This observation may be of interest to other biologists using SMRT sequencing in their research.

The NEB REBASE database predicted three putative DNA MTases in E. faecalis OG1RF, only one of which was active in OG1RF under the growth conditions used here. The expression level of OG1RF_11622 was robust compared to clpX, while expression levels of the other two DNA MTase genes were lower (≤1% of clpX levels) (Fig. 1). It is unclear what expression level would be sufficient to detect methylation activity. Functional linkage between OG1RF_11622 (M.EfaRFI) and 5′-GCWGC-3′ modification of the OG1RF genome was confirmed by digestion with the methylation-sensitive REases ApeKI and TseI (Fig. 4 and Table 1).

By expressing predicted DNA MTases in E. coli BL21(DE3), we determined that OG1RF_11823 encodes a DNA MTase that modifies 5′-CCGG-3′ with m4C, thereby providing protection from the methylation-sensitive REase HpaII. However, OG1RF gDNA is not protected from HpaII, most likely because of low expression of the OG1RF_11823 gene under laboratory growth conditions. Expression of OG1RF_11823 may be induced under certain growth conditions (stress, polymicrobial environments, etc.). The regulation of OG1RF_11823 is of interest for future study.

We did not find evidence for DNA MTase activity for OG1RF_10790, which is predicted to be an m5C DNA MTase (Table 2). It is possible that the depth of coverage attained by SMRT sequencing was not sufficient to detect m5C modification in the E. coli heterologous host, although we noted that a similar level of coverage detected 5′-G-m5C-WGC-3′ modification in OG1RF gDNA, albeit at a low frequency. While we confirmed overexpression of OG1RF_10790 in the E. coli host (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), it is possible that the protein is inactive in this background because of misfolding or the absence of required cofactors.

We found that the presence or absence of 5′-G-m5C-WGC-3′ modification in E. faecalis OG1RF significantly affected conjugative transfer of the model pheromone-responsive plasmid pCF10, albeit the magnitude of the effect was low (3-fold reduction in transconjugant yields). R-M system activity can reduce conjugation efficiency by <1 to >4 logs, the magnitude of which can depend on the type of R-M system involved, the number of recognition sites present on the plasmid, the methylation state of the DNA motif (full, hemi-, or no methylation), whether the motif is single or double stranded, and whether antirestriction strategies are employed by the plasmid (19, 65–70). During conjugation, a single plasmid strand is typically transferred, and a complementary strand is synthesized in the new host. For pCF10 conjugation in E. faecalis OG1RF, the relative timing of pCF10 complementary strand synthesis, M.EfaRFI methylation of new motifs, and R.EfaRFI recognition of unmodified or perhaps hemimethylated motifs could influence outcomes for individual recipient cells in the population. Activities of the EfaRFI system against single-stranded DNA and hemimethylated DNA are as yet unknown, and further studies will be required to assess its spectrum of biochemical activities. We note also that pCF10 harbors genes for a predicted ArdA protein within a Tn925 element and that ArdA proteins inhibit type I REases by acting as a DNA mimic (71–74). Whether the pCF10 ArdA has any impact on EfaRFI, a type II system, remains to be determined. As for whether the EfaRFI system would influence antibiotic resistance transfer outside laboratory conditions, the best tests would be in gastrointestinal tract colonization and infection models. We will address this point in the future.

Future work will also assess the distributions and diversity of R-M systems across the E. faecalis species by using the techniques described here. Lineage-specific systems could impact plasmid transfer efficiencies among enterococci and the bacteria with which they exchange DNA, contributing to the evolution of multidrug-resistant strains. OG1RF also possesses a type II CRISPR-Cas locus (10), and CRISPR-Cas and an R-M defense may act synergistically to protect OG1RF from MGE acquisition. Furthermore, genome modification influences gene expression patterns and mutation frequencies in bacteria (63), and this can now be assessed for E. faecalis OG1RF.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants K22AI099088 to K.L.P. and U01ES017166 to M.Q.Z.

We thank Lawrence Reitzer, Tamiko Oguri, and Richa Goel for assistance with Keio Collection E. coli strains, Juan Gonzalez and Corey Manley for assistance with RT-qPCR experiments, Valerie Price for assistance with cesium chloride density gradient centrifugation, Zhixing Feng for assistance with SMRT sequencing analysis, and Zhenyu Xuan for assistance with empirical modeling. We thank Rich Roberts and two anonymous reviewers for critical feedback on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.00130-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lebreton F, Willems RJL, Gilmore MS. 2 February 2014. Enterococcus diversity, origins in nature, and gut colonization. In Gilmore MS, Clewell DB, Ike Y, Shankar N (ed), Enterococci: from commensals to leading causes of drug resistant infection. Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston, MA: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK190427/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agudelo Higuita NI, Huycke MM. 4 February 2014. Enterococcal disease, epidemiology, and implications for treatment. In Gilmore MS, Clewell DB, Ike Y, Shankar N (ed), Enterococci: from commensals to leading causes of drug resistant infection. Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston, MA: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK190429/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sievert DM, Ricks P, Edwards JR, Schneider A, Patel J, Srinivasan A, Kallen A, Limbago B, Fridkin S, National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Team and Participating Facilities. 2013. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009-2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 34:1–14. doi: 10.1086/668770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kristich CJ, Rice LB, Arias CA. 6 February 2014. Enterococcal infection—treatment and antibiotic resistance. In Gilmore MS, Clewell DB, Ike Y, Shankar N (ed), Enterococci: from commensals to leading causes of drug resistant infection. Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston, MA: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK190420/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clewell DB, Weaver KE, Dunny GM, Coque TM, Francia MV, Hayes F. 9 February 2014. Extrachromosomal and mobile elements in enterococci: transmission, maintenance, and epidemiology. In Gilmore MS, Clewell DB, Ike Y, Shankar N (ed), Enterococci: from commensals to leading causes of drug resistant infection. Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston, MA: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK190430/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weigel LM, Clewell DB, Gill SR, Clark NC, McDougal LK, Flannagan SE, Kolonay JF, Shetty J, Killgore GE, Tenover FC. 2003. Genetic analysis of a high-level vancomycin-resistant isolate of Staphylococcus aureus. Science 302:1569–1571. doi: 10.1126/science.1090956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jasni AS, Mullany P, Hussain H, Roberts AP. 2010. Demonstration of conjugative transposon (Tn5397)-mediated horizontal gene transfer between Clostridium difficile and Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:4924–4926. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00496-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gold OG, Jordan HV, van Houte J. 1975. The prevalence of enterococci in the human mouth and their pathogenicity in animal models. Arch Oral Biol 20:473–477. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(75)90236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sahm DF, Kissinger J, Gilmore MS, Murray PR, Mulder R, Solliday J, Clarke B. 1989. In vitro susceptibility studies of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 33:1588–1591. doi: 10.1128/AAC.33.9.1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourgogne A, Garsin DA, Qin X, Singh KV, Sillanpaa J, Yerrapragada S, Ding Y, Dugan-Rocha S, Buhay C, Shen H, Chen G, Williams G, Muzny D, Maadani A, Fox KA, Gioia J, Chen L, Shang Y, Arias CA, Nallapareddy SR, Zhao M, Prakash VP, Chowdhury S, Jiang H, Gibbs RA, Murray BE, Highlander SK, Weinstock GM. 2008. Large scale variation in Enterococcus faecalis illustrated by the genome analysis of strain OG1RF. Genome Biol 9:R110. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-7-r110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McBride SM, Fischetti VA, Leblanc DJ, Moellering RC Jr, Gilmore MS. 2007. Genetic diversity among Enterococcus faecalis. PLoS One 2:e582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paulsen IT, Banerjei L, Myers GS, Nelson KE, Seshadri R, Read TD, Fouts DE, Eisen JA, Gill SR, Heidelberg JF, Tettelin H, Dodson RJ, Umayam L, Brinkac L, Beanan M, Daugherty S, DeBoy RT, Durkin S, Kolonay J, Madupu R, Nelson W, Vamathevan J, Tran B, Upton J, Hansen T, Shetty J, Khouri H, Utterback T, Radune D, Ketchum KA, Dougherty BA, Fraser CM. 2003. Role of mobile DNA in the evolution of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Science 299:2071–2074. doi: 10.1126/science.1080613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palmer KL, Godfrey P, Griggs A, Kos VN, Zucker J, Desjardins C, Cerqueira G, Gevers D, Walker S, Wortman J, Feldgarden M, Haas B, Birren B, Gilmore MS. 2012. Comparative genomics of enterococci: variation in Enterococcus faecalis, clade structure in E. faecium, and defining characteristics of E. gallinarum and E. casseliflavus. mBio 3(1):e00318-11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00318-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shankar N, Baghdayan AS, Gilmore MS. 2002. Modulation of virulence within a pathogenicity island in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Nature 417:746–750. doi: 10.1038/nature00802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galloway-Pena JR, Bourgogne A, Qin X, Murray BE. 2011. Diversity of the fsr-gelE region of the Enterococcus faecalis genome but conservation in strains with partial deletions of the fsr operon. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:442–451. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00756-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solheim M, Brekke MC, Snipen LG, Willems RJ, Nes IF, Brede DA. 2011. Comparative genomic analysis reveals significant enrichment of mobile genetic elements and genes encoding surface structure-proteins in hospital-associated clonal complex 2 Enterococcus faecalis. BMC Microbiol 11:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palmer KL, Gilmore MS. 2010. Multidrug-resistant enterococci lack CRISPR-cas. mBio 1(4):e00227-10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00227-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiedenheft B, Sternberg SH, Doudna JA. 2012. RNA-guided genetic silencing systems in bacteria and archaea. Nature 482:331–338. doi: 10.1038/nature10886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tock MR, Dryden DT. 2005. The biology of restriction and anti-restriction. Curr Opin Microbiol 8:466–472. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janulaitis A, Petrusyte M, Maneliene Z, Klimasauskas S, Butkus V. 1992. Purification and properties of the Eco57I restriction endonuclease and methylase–prototypes of a new class (type IV). Nucleic Acids Res 20:6043–6049. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.22.6043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis BM, Chao MC, Waldor MK. 2013. Entering the era of bacterial epigenomics with single molecule real time DNA sequencing. Curr Opin Microbiol 16:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duerkop BA, Palmer KL, Horsburgh MJ. 11 February 2014. Enterococcal bacteriophages and genome defense. In Gilmore MS, Clewell DB, Ike Y, Shankar N (ed), Enterococci: from commensals to leading causes of drug resistant infection. Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston, MA: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK190419/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu R, King CT, Jay E. 1978. A new sequence-specific endonuclease from Streptococcus faecalis subsp. zymogenes. Gene 4:329–336. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(78)90049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okhapkina SS, Netesova NA, Golikova LN, Seregina EV, Sosnovtsev SV, Abdurashitov MA, Degtiarev S. 2002. Comparison of the homologous SfeI and LlaBI restriction-modification systems. Mol Biol (Mosk) 36:432–437. (In Russian.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radlinska M, Piekarowicz A, Galimand M, Bujnicki JM. 2005. Cloning and preliminary characterization of a GATC-specific β2-class DNA:m6A methyltransferase encoded by transposon Tn1549 from Enterococcus spp. Pol J Microbiol 54:249–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts RJ. 1982. Restriction and modification enzymes and their recognition sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 10:r117–r144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts RJ, Vincze T, Posfai J, Macelis D. 2010. REBASE, a database for DNA restriction and modification: enzymes, genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 38:D234–D236. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manson JM, Keis S, Smith JMB, Cook GM. 2003. A clonal lineage of VanA-type Enterococcus faecalis predominates in vancomycin-resistant enterococci isolated in New Zealand. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:204–210. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.1.204-210.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, Frith M, Grant CE, Clementi L, Ren J, Li WW, Noble WS. 2009. MEME Suite: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res 37:W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li LC, Dahiya R. 2002. MethPrimer: designing primers for methylation PCRs. Bioinformatics 18:1427–1431. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.11.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio Collection. Mol Syst Biol 2:2006.0008. doi: 10.1038/msb4100050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krueger F, Andrews SR. 2011. Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for bisulfite-Seq applications. Bioinformatics 27:1571–1572. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thurlow LR, Thomas VC, Hancock LE. 2009. Capsular polysaccharide production in Enterococcus faecalis and contribution of CpsF to capsule serospecificity. J Bacteriol 191:6203–6210. doi: 10.1128/JB.00592-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shepard BD, Gilmore MS. 1995. Electroporation and efficient transformation of Enterococcus faecalis grown in high concentrations of glycine. Methods Mol Biol 47:217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trieu-Cuot P, Carlier C, Poyart-Salmeron C, Courvalin P. 1990. A pair of mobilizable shuttle vectors conferring resistance to spectinomycin for molecular cloning in Escherichia coli and in gram-positive bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res 18:4296. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.14.4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Debroy S, van der Hoeven R, Singh KV, Gao P, Harvey BR, Murray BE, Garsin DA. 2012. Development of a genomic site for gene integration and expression in Enterococcus faecalis. J Microbiol Methods 90:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dunny GM. 2007. The peptide pheromone-inducible conjugation system of Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pCF10: cell-cell signalling, gene transfer, complexity and evolution. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 362:1185–1193. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirt H, Manias DA, Bryan EM, Klein JR, Marklund JK, Staddon JH, Paustian ML, Kapur V, Dunny GM. 2005. Characterization of the pheromone response of the Enterococcus faecalis conjugative plasmid pCF10: complete sequence and comparative analysis of the transcriptional and phenotypic responses of pCF10-containing cells to pheromone induction. J Bacteriol 187:1044–1054. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.3.1044-1054.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manson JM, Hancock LE, Gilmore MS. 2010. Mechanism of chromosomal transfer of Enterococcus faecalis pathogenicity island, capsule, antimicrobial resistance, and other traits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:12269–12274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000139107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bae T, Kozlowicz B, Dunny GM. 2002. Two targets in pCF10 DNA for PrgX binding: their role in production of Qa and prgX mRNA and in regulation of pheromone-inducible conjugation. J Mol Biol 315:995–1007. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bryan EM, Bae T, Kleerebezem M, Dunny GM. 2000. Improved vectors for nisin-controlled expression in gram-positive bacteria. Plasmid 44:183–190. doi: 10.1006/plas.2000.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garger SJ, Griffith OM, Grill LK. 1983. Rapid purification of plasmid DNA by a single centrifugation in a two-step cesium chloride-ethidium bromide gradient. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 117:835–842. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(83)91672-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perez-Casal J, Caparon MG, Scott JR. 1991. Mry, a trans-acting positive regulator of the M protein gene of Streptococcus pyogenes with similarity to the receptor proteins of two-component regulatory systems. J Bacteriol 173:2617–2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kasarjian JK, Iida M, Ryu J. 2003. New restriction enzymes discovered from Escherichia coli clinical strains using a plasmid transformation method. Nucleic Acids Res 31:e22. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baker TA, Sauer RT. 2012. ClpXP, an ATP-powered unfolding and protein-degradation machine. Biochim Biophys Acta 1823:15–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mehmeti I, Faergestad EM, Bekker M, Snipen L, Nes IF, Holo H. 2012. Growth rate-dependent control in Enterococcus faecalis: effects on the transcriptome and proteome, and strong regulation of lactate dehydrogenase. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:170–176. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06604-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murray IA, Clark TA, Morgan RD, Boitano M, Anton BP, Luong K, Fomenkov A, Turner SW, Korlach J, Roberts RJ. 2012. The methylomes of six bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res 40:11450–11462. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fang G, Munera D, Friedman DI, Mandlik A, Chao MC, Banerjee O, Feng Z, Losic B, Mahajan MC, Jabado OJ, Deikus G, Clark TA, Luong K, Murray IA, Davis BM, Keren-Paz A, Chess A, Roberts RJ, Korlach J, Turner SW, Kumar V, Waldor MK, Schadt EE. 2012. Genome-wide mapping of methylated adenine residues in pathogenic Escherichia coli using single-molecule real-time sequencing. Nat Biotechnol 30:1232–1239. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krebes J, Morgan RD, Bunk B, Sproer C, Luong K, Parusel R, Anton BP, Konig C, Josenhans C, Overmann J, Roberts RJ, Korlach J, Suerbaum S. 2014. The complex methylome of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nucleic Acids Res 42:2415–2432. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lluch-Senar M, Luong K, Llorens-Rico V, Delgado J, Fang G, Spittle K, Clark TA, Schadt E, Turner SW, Korlach J, Serrano L. 2013. Comprehensive methylome characterization of Mycoplasma genitalium and Mycoplasma pneumoniae at single-base resolution. PLoS Genet 9:e1003191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bendall ML, Luong K, Wetmore KM, Blow M, Korlach J, Deutschbauer A, Malmstrom RR. 2013. Exploring the roles of DNA methylation in the metal-reducing bacterium Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. J Bacteriol 195:4966–4974. doi: 10.1128/JB.00935-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kozdon JB, Melfi MD, Luong K, Clark TA, Boitano M, Wang S, Zhou B, Gonzalez D, Collier J, Turner SW, Korlach J, Shapiro L, McAdams HH. 2013. Global methylation state at base-pair resolution of the Caulobacter genome throughout the cell cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:E4658–E4667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319315110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clark TA, Lu X, Luong K, Dai Q, Boitano M, Turner SW, He C, Korlach J. 2013. Enhanced 5-methylcytosine detection in single-molecule, real-time sequencing via Tet1 oxidation. BMC Biol 11:4. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-11-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang T, Muraih JK, Tishbi N, Herskowitz J, Victor RL, Silverman J, Uwumarenogie S, Taylor SD, Palmer M, Mintzer E. 2014. Cardiolipin prevents membrane translocation and permeabilization by daptomycin. J Biol Chem 289:11584–11591. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.554444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Flusberg BA, Webster DR, Lee JH, Travers KJ, Olivares EC, Clark TA, Korlach J, Turner SW. 2010. Direct detection of DNA methylation during single-molecule, real-time sequencing. Nat Methods 7:461–465. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clark TA, Murray IA, Morgan RD, Kislyuk AO, Spittle KE, Boitano M, Fomenkov A, Roberts RJ, Korlach J. 2012. Characterization of DNA methyltransferase specificities using single-molecule, real-time DNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res 40:e29. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kobayashi H, Kono T. 2012. DNA methylation analysis of germ cells by using bisulfite-based sequencing methods. Methods Mol Biol 825:223–235. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-436-0_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lister R, Ecker JR. 2009. Finding the fifth base: genome-wide sequencing of cytosine methylation. Genome Res 19:959–966. doi: 10.1101/gr.083451.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kahramanoglou C, Prieto AI, Khedkar S, Haase B, Gupta A, Benes V, Fraser GM, Luscombe NM, Seshasayee AS. 2012. Genomics of DNA cytosine methylation in Escherichia coli reveals its role in stationary phase transcription. Nat Commun 3:886. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Frommer M, McDonald LE, Millar DS, Collis CM, Watt F, Grigg GW, Molloy PL, Paul CL. 1992. A genomic sequencing protocol that yields a positive display of 5-methylcytosine residues in individual DNA strands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89:1827–1831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vilkaitis G, Klimasauskas S. 1999. Bisulfite sequencing protocol displays both 5-methylcytosine and N4-methylcytosine. Anal Biochem 271:116–119. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roberts RJ, Belfort M, Bestor T, Bhagwat AS, Bickle TA, Bitinaite J, Blumenthal RM, Degtyarev S, Dryden DT, Dybvig K, Firman K, Gromova ES, Gumport RI, Halford SE, Hattman S, Heitman J, Hornby DP, Janulaitis A, Jeltsch A, Josephsen J, Kiss A, Klaenhammer TR, Kobayashi I, Kong H, Kruger DH, Lacks S, Marinus MG, Miyahara M, Morgan RD, Murray NE, Nagaraja V, Piekarowicz A, Pingoud A, Raleigh E, Rao DN, Reich N, Repin VE, Selker EU, Shaw PC, Stein DC, Stoddard BL, Szybalski W, Trautner TA, Van Etten JL, Vitor JM, Wilson GG, Xu SY. 2003. A nomenclature for restriction enzymes, DNA methyltransferases, homing endonucleases and their genes. Nucleic Acids Res 31:1805–1812. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vasu K, Nagaraja V. 2013. Diverse functions of restriction-modification systems in addition to cellular defense. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 77:53–72. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00044-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Krueger F, Kreck B, Franke A, Andrews SR. 2012. DNA methylome analysis using short bisulfite sequencing data. Nat Methods 9:145–151. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wilkins BM. 2002. Plasmid promiscuity: meeting the challenge of DNA immigration control. Environ Microbiol 4:495–500. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ohtani N, Sato M, Tomita M, Itaya M. 2008. Restriction on conjugational transfer of pLS20 in Bacillus subtilis 168. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 72:2472–2475. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Possoz C, Ribard C, Gagnat J, Pernodet JL, Guerineau M. 2001. The integrative element pSAM2 from Streptomyces: kinetics and mode of conjugal transfer. Mol Microbiol 42:159–166. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Read TD, Thomas AT, Wilkins BM. 1992. Evasion of type I and type II DNA restriction systems by IncI1 plasmid CoIIb-P9 during transfer by bacterial conjugation. Mol Microbiol 6:1933–1941. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]