Abstract

Objective

To evaluate this impact on male and female English medical graduates by estimating the total time and amount repaid on loans taken out with the UK's Student Loans Company (SLC).

Setting

UK.

Participants

4286 respondents with a medical degree in the Labour Force Surveys administered by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) between 1997 and 2014.

Outcomes

Age-salary profiles were generated to estimate the repayment profiles for different levels of initial graduate debt.

Results

2195 female and 2149 male medical graduates were interviewed by the ONS. Those working full-time (73.1% females and 96.1% males) were analysed in greater depth. Following standardisation to 2014 prices, average full-time male graduates earned up to 35% more than females by the age of 55. The initial graduate debt from tuition fees alone amounts to £39 945.69. Owing to interest charges on this debt the average full-time male graduate repays £57 303 over 20 years, while the average female earns less and so repays £61 809 over 26 years. When additional SLC loans are required for maintenance, the initial graduate debt can be as high as £81 916 and, as SLC debt is written off 30 years after graduation, the average female repays £75 786 while the average male repays £110 644.

Conclusions

Medical graduates on an average salary are unlikely to repay their SLC debt in full. This is a consequence of higher university fees and as SLC debt is written off 30 years after graduation. This results in the average female graduate repaying more when debt is low, but a lower amount when debt is high compared to male graduates.

Keywords: MEDICAL EDUCATION & TRAINING, JOURNALISM (see Medical Journalism)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study reports the lifetime cost to medical graduates of repaying the Student Loans Company under the new £9000 annual fees regime.

Once loans for living costs are factored in, medical graduates are unlikely to repay their debt in full before it is written off at the end of the 30th year after graduation.

If the amount borrowed is more than about £50 000, someone on an average female medical graduate salary will typically repay less than her male counterpart because she earns less and repayments are mainly based on the level of earnings.

However, if the amount borrowed is less than about £50 000, those on the average female graduate salary repay more than their male counterparts as they accrue more interest charges.

The analysis in this study is based on the assumption that the pay scales of medical graduates will rise in line with price inflation and that there will be no changes to the terms of the student loans. Small changes in either of these two sets of assumptions could have huge implications for medical graduates’ actual lifetime repayments over the next 30 years.

Introduction

Over the past decade, annual tuition fees for English students attending UK universities have risen from £1000 when introduced in 1998 to £9000 currently.1 This is mirrored by a rise in graduate debt, which is particularly important for courses that involve prolonged periods of study such as medicine. The British Medical Association (BMA) has suggested that graduate debt for current medical students could be in excess of £70 000.2 Such levels of graduate debt may affect the recruitment of students to a career in medicine in the UK as some may choose alternative careers and others may decide to study medicine abroad.

The Student Loans Company (SLC), under its ‘Plan 2’ scheme introduced in September 2012, changed both the amounts that it will lend to students and the rules governing the repayment of the resulting debt. The SLC will lend students £9000 per annum (pa) for tuition alone plus a separate maintenance loan3 to cover students’ housing costs and food. Means tested grants and bursaries for final year tuition fees are available for selected students.4 Currently, SLC debts are automatically written off 30 years after graduating, regardless of the remaining debt. Repayments are based on 9% of salary above £21 000 (at 2016 prices under the current SLC Plan 2) rather than the amount of debt. Early research5 6 has analysed the implications of the SLC Plan 2 scheme, but was limited to those on average graduate salaries and 3-year degrees. However, to date, there has been no detailed analysis of the implications for the prolonged periods of study and higher debt for courses such as medicine.

To understand how much a medical graduate might repay, an accurate estimation of gross graduate salaries is required. For medical graduates, pay scales7 do not reflect the actual salaries earned as these can depend on additional work hours, sessions worked, flexible working and career breaks. In addition, there are notable differences between the salaries of male and female medical graduates.8 9

To overcome these issues, a representative data set of medical graduates’ actual salaries is required. The Labour Force Survey (LFS) is the largest survey undertaken by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) that records household salaries. The LFS collects data continuously on 1% of the UK population each year and provides official measures on employment rates.10 To ensure an even coverage of the UK population and minimise sources of sampling bias, the ONS samples households randomly using the Royal Mail’s Postcode Address File. Despite the lengthy questionnaire format, the ONS conducts interviews in person or over the telephone to maximise response rates.11

In this study, the LFS was used to calculate salary profiles for the average medical graduate. Using this and the repayment schedules from the SLC, a model for the repayment of graduate debt for English students studying in the UK was developed. Total amounts repaid over the lifetime of these SLC loans were calculated based on different amounts of graduate debt.

Methods

Male and female medical graduates’ salaries following graduation

LFS data between April 1997 and June 2014 were used10 to obtain a substantial sample of medical graduates on which to base our calculations of average earnings. Their salaries were then grouped by age and gender.

This sample of medical graduates included those who may or may not be practising clinicians or who work in or outside hospital settings. The main analysis considered full-time workers alone, defined as those working more than 30 hours per week,12 while a supplementary analysis included both part-time and full-time workers. Gross salaries and other monetary values were re-indexed to 2014 prices using the retail prices index (code CHAW) from the ONS.13 Caution must be exercised when collecting data over such a long time period because average real salaries change over time, but this was necessary to achieve a reasonably large sample size. Fortunately, from a research standpoint, medical salaries have risen almost in line with Retail Price Inflation (RPI) so that they have hardly risen in real terms (see online supplementary figure S1). It was therefore assumed that future salaries will remain steady in real terms.

Debt from fees for a medical degree

It is assumed here that a medical degree takes 5 years to complete and that most Universities will charge the maximum allowable £9000 pa for tuition fees. It should be realised that this is currently only true for English students who study in the UK. Tuition fees vary within the UK by country of study and student's country of origin. For example, Scottish students studying in Scotland have most of their £9000 fees paid by Student Awards Agency for Scotland and there are varying maximum amounts both Welsh and Northern Irish students are expected to pay.

The BMA and the National Health Service (NHS) provide a bursary for the final year's fees, so this was discounted. Repayment calculations were based on the SLC ‘Plan 2’ scheme that allows loans up to £9000 pa with annual interest at a rate of 3% plus RPI. These interest charges begin when the loan starts and continue thereafter. Therefore, a medical graduate who borrows to cover all tuition fees under the current ‘Plan 2’ system, at 2014 prices, would graduate with a debt of £39 946 (see equation 1 in the online supplementary file).

Debt from maintenance loans for a medical degree

The SLC ‘Plan 2’ also offers maintenance loans of £4375 for students living at home; £7675 for students living in London; and £5500 for students living at universities elsewhere in the UK. Total maintenance debt for a student living at home was therefore calculated as £23 924, for a student living away from home and outside of London as £30 076, and for a student who studies in London and away from home as £41 970 (see equations 2–4 in the online supplementary file).

Repayment of fees (for any level of debt)

Under the terms of the SLC ‘Plan 2’, repayments are based on graduate gross income, not the level of debt. As per these rules, the Pension Contribution Rate (PCR) was subtracted from the gross salary (see online supplementary table S114 15). Models of the yearly repayment schedules were created (see equation 5 in the online supplementary file). This analysis assumed that repayments are made each year rather than each month. It was also assumed that interest is charged at the same rate (3% plus RPI) as is during the degree and for salaries above £41 000, given that medical salaries frequently exceed this. The formula used to calculate the running graduate debt at the end of each year is equation (6) in the online supplementary file.

Analyses

These were conducted using StataCorp Stata Statistical Software (Release V.13. 2013 College Station, Texas, USA: StataCorp LP16). The report was written in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

Results

Sample demographics

The overall LFS response rates varied between 75% and 50% during the period studied.11 There were 2195 female and 2149 male medical graduates identified in the LFS. The proportion of female medical graduates increased from 39.3% to 56.0% over the period despite the female population within the LFS remaining constant at 51.5%. General demographics are shown in table 1. There were significant gender differences in age groups, proportions in hospital practice and numbers working full time. For the rest of the reported analysis, only full-time workers were included. This equated to 1589 females and 2029 males. For this group of full-time workers, there was a greater proportion of females in the 23–29 age range (59.4%) and a greater proportion of males in the 40–64 age range (63.4%). Furthermore, 73.6% of males worked in a hospital setting compared to 66.7% of females.

Table 1.

Gender and age composition of LFS respondents with a medical degree: April 1997–June 2014

| Male | Female | Test for difference in gender proportions |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 test | p Value | |||

| Age range | ||||

| 23–29 | 327 (15) | 519 (24) | 39.6 | <0.001 |

| 30–39 | 734 (34) | 791 (36) | 1.1 | 0.294 |

| 40–64 | 1088 (51) | 885 (40) | 25.4 | <0.001 |

| Total | 2149 (100%) | 2195 (100%) | 66.1 | <0.001 |

| Place of work | ||||

| Hospital | 1565 (73) | 1333 (61) | 23.8 | <0.001 |

| Non-hospital | 584 (27) | 862 (39) | 47.7 | <0.001 |

| Total | 2149 (100%) | 2195 (100%) | 71.5 | <0.001 |

| Type of work | ||||

| Part-time | 82 (4) | 586 (27) | 366.4 | <0.001 |

| Full-time | 2029 (96) | 1589 (73) | 67.5 | <0.001 |

| Total | 2111 (100%) | 2175 (100%) | 432.9 | <0.001 |

| t test | p Value | |||

|

Average weekly hours among full-time workers |

£48.95 [11] | £44.50 [10] | 12.5 | <0.001 |

|

Average hourly wage among full-time workers |

£30.74 [15] | £24.48 [12] | 13.5 | <0.001 |

Values in parentheses () are column percentages.

Values in square brackets [ ] are standard deviations.

LFS, Labour Force Survey.

Age-salary profiles

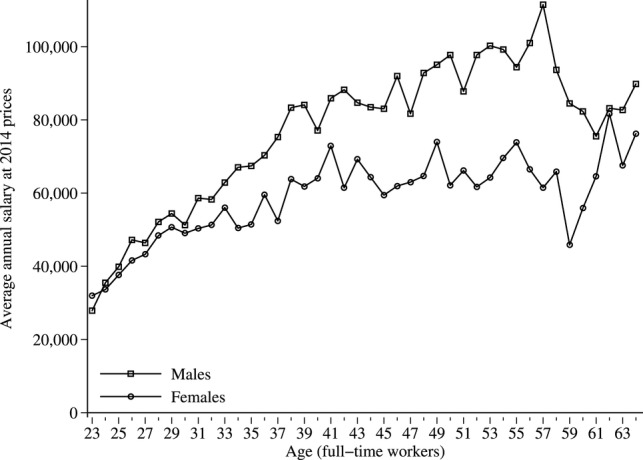

Average full-time salaries increased with age and then gradually decreased after the age of 55 (figure 1). Though female and male graduate salaries were initially similar, they gradually diverged such that at the age of 55, males earned 35% more than females. The gender difference in annual earnings is mainly due to differences in hourly wage rates rather than number of hours worked (table 1).

Figure 1.

Average salaries for medical graduates working full-time (over 30 basic hours per week).

Graduate debt and repayments

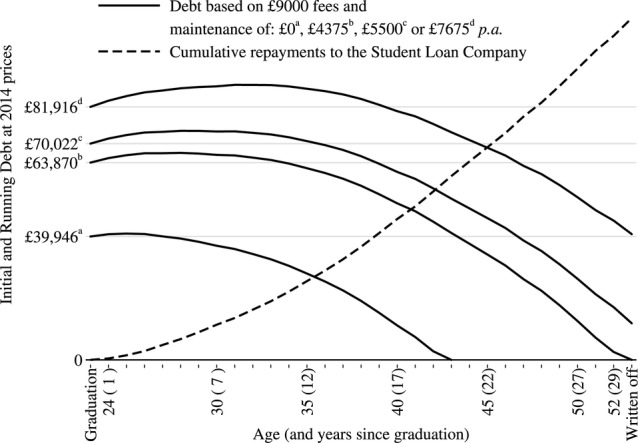

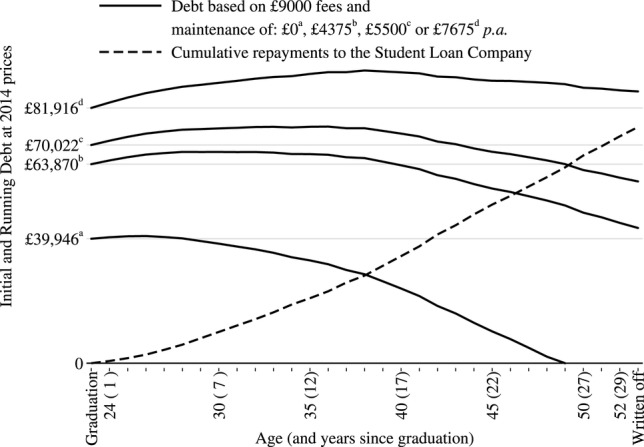

Using the resulting average age-salary profiles, projected future repayments and cumulative debt for male and female medical graduates who work full-time were generated, as shown in figures 2 and 3 (see online supplementary tables S2 and S3). Considering the repayments of those who borrowed £39 945.69 for tuition fees alone, full-time male graduates would repay a total of £57 303 and clear their debt over 20 years. Full-time female graduates would repay a total of £61 809 and clear their debt over 26 years for the same initial debt as males.

Figure 2.

Average debt repayment profiles for full-time male medical graduates.

Figure 3.

Average debt repayment profiles for full-time female medical graduates.

Calculation of future repayments for full-time medical graduates who also required loans for maintenance costs showed that the yearly repayments and the total repaid over 30 years will remain the same, regardless of the level of debt at graduation (figures 2 and 3 and online supplementary tables S2 and S3), with the caveat that the average male graduate who borrows £4375 p.a. for maintenance may repay all his debt in the 30th year of work. The total repaid, however, varies by gender with the average female repaying less than the average male. This is linked to a lower average female medical graduate salary.

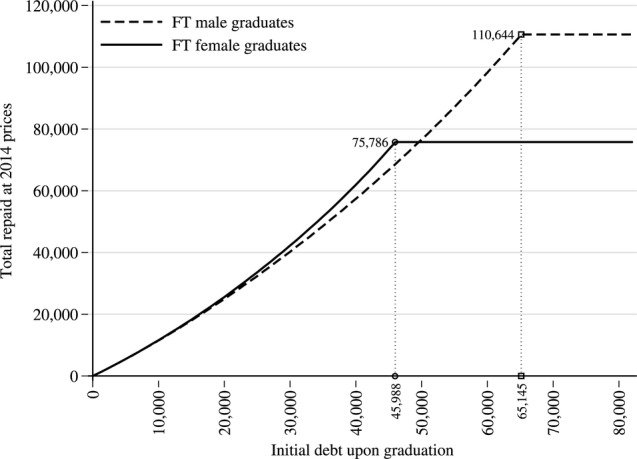

For full-time medical graduates, figure 4 illustrates the total repaid for any level of initial debt. The total repaid increases with the initial level of debt, but only up to a certain level as any remaining debt is written off after 30 years. The repayment profiles for full-time female and male medical graduates are different because females typically earn less. For full-time female graduates, the maximum total repayment is £75 786 for any initial debt above £45 988. For full-time male graduates, this maximum repayment is £110 644 for any initial debt above £65 145, again as any debt is written off after 30 years. As demonstrated by the ‘crossover point’ in figure 4, for an initial debt below almost exactly £50 000, female graduates repay more despite earning less because their debt lasts longer and accrues more interest charges. For graduates with initial debt above £50 000, male graduates typically repay more because their average yearly salaries are higher.

Figure 4.

Initial debt to total repayment profiles for full-time medical graduates.

Repayment models were also created to include both part-time and full-time medical graduates, as some graduates will have periods of part-time work during their careers (see online supplementary figures S2 and S3). As female graduates now have even lower average yearly salaries, the maximum total repayment falls to £61 410, and therefore more debt is written off in the 30th year. For very low levels of initial debt, female graduates who earn less may repay more compared to higher earning females as they accrue more interest charges. This is less obvious for male graduates due to the low proportion of part-time workers in this group.

Discussion

This is the first analysis concentrating on UK LFS respondents with a medical degree. It confirms that medical graduate salaries are correlated with gender. This gender difference has an impact on the repayment of potential graduate debt. For those graduates who are able to repay the debt in the 30-year period, a higher yearly salary is advantageous as early repayment means fewer interest charges are accrued. Curiously, for those who do not repay their total debt within the 30-year period, as is the case for the average female medical graduates, a lower salary means they repay less because yearly repayments are lower and the residual debt is written off.

While the overall LFS response rate is 50–70%, the specific response rate for medical graduates is not known.11 Though it is unclear if the LFS represents a true cross section of the 250 000 doctors registered with the General Medical Council (GMC), the observed rise in the number of female medical graduates within the LFS is similar to that seen by official GMC statistics.17 This is despite a constant 51.5% of females in the entire LFS sample. In addition, the proportions of LFS respondents working in hospital and non-hospital settings are similar to those reported by the GMC specialist and general practice (ie, family doctor) registers. Taken together, this suggests that the sampling of medical graduates by the ONS is representative.

Assumptions were made in the construction of the model and projected salaries. These calculations focused on the patterns of debt repayment for a medical graduate on an average salary. The impact of voluntary early repayments or non-SLC bank loans were not analysed here, but it has been estimated that non-SLC loans (eg, credit cards, overdraft and bank loans) constitute only 17% of the overall debt for individual medical graduates.2 It is unclear if this is the case for all medical graduates or whether this is limited to certain groups, for example, graduates from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. The models in this analysis assumed that medical graduate salaries will rise in line with inflation as they have done between 1999 and 2014 (see online supplementary figure S1) Finally, it should be noted that this study investigated the salaries and repayments of debt for medical graduates and no attempt was made to analyse the costs of failing to complete a degree or estimate the net returns of investing in a medical degree.

The disparity between male and female salaries is well documented across different careers and countries18 19 and similar patterns have been documented in medicine.7 20 21 Reports based on non-selected samples of less than a thousand UK medical respondents again suggest that gender differences in salaries exist despite rigid pay scales.7 In the LFS data presented here, this gender gap in salaries begins at age 30, widens subsequently and is largely the result of a significant hourly wage difference between the genders. A range of factors have been cited as an explanation for these gender-wage differences which not only include discrimination but also career breaks, career choices, part-time work and motherhood.22 23

University tuition fees have risen since they were introduced in 1998, as has graduate debt. Prior to the substantial 2012 rise in tuition fees, the Push National Debt Survey 2011 calculated average yearly student debt at £5681 from a poll of over 2000 university students in England.21 The BMA has estimated that medical graduates could owe £70 000 in loans despite NHS bursaries. The present calculations suggest that the typical debt for medical students living away from home could be nearly £82 000 at 2014 prices when one includes the projected interest charges accrued during the time at university.

The National Audit Office24 (NAO) presented a single simulation for a doctor graduating with an initial debt of £71 000, suggesting that they would clear the debt 25 years after graduating. However, in the simulations presented here, neither a male nor a female medical graduate with an initial debt of £70 022 (see column 9 in online supplementary tables S2 and S3) would ever repay the debt before it is written off. This difference is because the NAO analysis is based on salaries from doctors’ pay scales while our analysis is based on survey data on the earnings of all medical graduates.

Furthermore, gender differences in medical salaries highlight an inconsistent relationship between salaries and total repayments of debt. The complexities of the SLC loan contract mean that the effects on total repayments of lower female salaries vary with the level of initial graduate debt. For low levels of initial graduate debt, females will typically end up repaying more than males because their debt accrues more interest charges. For high levels of initial graduate debt, females could end up repaying less because their salaries are typically lower and the debt is written off after the 30th year. This possibility of an inverse relationship between lifetime repayments and earnings, at higher levels of earnings, does not seem to have been documented elsewhere.

Student debt is a particularly emotive issue in many countries and has been widely discussed in the UK press25 26 and academic research.27 28 It seems reasonable that these repayment variations may actually exist across many graduate careers in the UK. It is also apparent that at the current level of fees, even small changes in the student loan contract will have substantial implications for lifetime wealth across different income groups, across male and female graduates, and on the sustainability of the student loans system.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge access to the Labour Force Surveys produced by the Office for National Statistics and distributed by the UK Data Service under usage number 74764. The authors thank attendees at the 2014 Work and Pensions Economics Group conference at the University of Sheffield, sponsored by the Department of Work and Pensions, for their comments. In addition, the authors thank Professor Peter Davies (Professor of Education Policy Research at the University of Birmingham), Mr Mike Hallissey (Deputy Medical Director at University Hospital Birmingham) and Professor Shervanthi Homer-Vanniasinkam (Professor of Surgery at University of Warwick Medical School) for their comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: MGE and RSV participated in the conception, design, analysis, writing and editing of this study. FC, KM and DA participated in the design and writing of the manuscript. MGE participated in the statistical analysis. MGE and RSV are the guarantors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data including supplementary data have been submitted. All original data can be accessed from the Labour Force Surveys produced by the Office for National Statistics and distributed by the UK Data Service under usage number 74764.

References

- 1.Great Britain. Department of Education. Higher Education Act (2004). London: The Stationery Office.

- 2.British Medical Association. Medical Students’ Finance Survey Academic year 2010/11 (p.41, Fig.30). http://bma.org.uk/search?query=mscfinancesurvey2011 (accessed 12 Aug 2014).

- 3.Student Loans Company, “Student Loan Repayment Interest Rates”. http://www.studentloanrepayment.co.uk/portal/page?_pageid= 93,6678755&_dad=portal&_schema=portal (accessed 20 Jul 2014).

- 4.NHS Business Services Authority, Student Bursaries. http://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/Students/816.aspx (accessed 20 Jul 2014).

- 5.Chowdry H, Dearden L, Goodman A et al. The distributional impact of the 2012–13 higher education funding reforms in England. Fiscal Stud 2012;33:211–36. 10.1111/j.1475-5890.2012.00159.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper S. It is a Graduate Tax 2011. http://www.physics.ox.ac.uk/Users/scooper/StudentFees (accessed 25 Aug 2014).

- 7.British Medical Association, Pay Scales. http://bma.org.uk/practical-support-at-work/pay-fees-allowances/pay-scales (accessed 20 Jul 2014).

- 8.Appleby J. Is there equal pay in healthcare? Not if you are a doctor. BMJ 2012;345:e6191 10.1136/bmj.e6191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dresler CM, Padgett DL, Mackinnon SE et al. Experiences of women in cardiothoracic surgery: a gender comparison. Arch Surg 1996;131:1128–34. 10.1001/archsurg.1996.01430230010002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Office for National Statistics, Labour Force Survey. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/method-quality/specific/labour-market/labour-market-statistics/index.html (accessed 20 Jul 2014).

- 11.Office for National Statistics, Labour Force Survey. Performance and Quality Monitoring Report, October to December 2011. London: Office for National Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gannon B, Roberts J. Part-time work and health among older workers in Ireland and Britain. Appl Econ 2011;43:4749–57. 10.1080/00036846.2010.498354 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Office for National Statistics, Datasets and Reference Tables. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/datasets-and-tables/index.html (accessed 13 Jan 2014).

- 14.The National Health Service Pension Scheme and Injury Benefits (Amendment) Regulations 2012. Statutory Instruments 2012 No. 610 London: HMSO. [Google Scholar]

- 15.NHS Employers Newsletter, January 2014. http://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/Documents/Pensions/TN01_-_2014_-_Employer_Newsletter.pdf (accessed 29 Sep 2014).

- 16.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.General Medical Council. List of Registered Medical Practitioners—statistics. http://www.gmc-uk.org/doctors/register/search_stats.asp (accessed 20 Jul 2014).

- 18.Gerhart B. Gender differences in current and starting salaries: the role of performance, college major, and job title. Ind Labor Relations Rev 1990;43:418–33. 10.2307/2524131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ginther DK, Hayes KJ. Gender differences in salary and promotion for faculty in the humanities 1977–1995. J Hum Resour 2003;38: 34–73. 10.2307/1558755 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Stewart A et al. Gender differences in salary in a recent cohort of early-career physician-researchers. Acad Med 2013;88:1689–99. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a71519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laine C, Turner BJ. Unequal pay for equal work: the gender gap in academic medicine. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:238–40. 10.7326/0003-4819-141-3-200408030-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardill I, Watson R. Career priorities within dual career households: an analysis of the impact of child rearing upon gender participation rates and earnings. Ind Relat J 2004;35:19–37. 10.1111/j.1468-2338.2004.00298.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waldfogel J. Understanding the “family gap” in pay for women with children. J Econ Perspect 1998;12:137–56. 10.1257/jep.12.1.137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Audit Office, Student loan repayments, Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General, (Fig.2) 2013;HC 818 London: The Stationery Office. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gardner R. Tuition fees: Three quarters of students won't be able to pay off their debt. The Independent 2014. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/education/higher/tuition-fees-three-quarters-of-students-wont-be-able-to-pay-off-their-debt-9866446.html (accessed 18 Nov 2014).

- 26.Weale S. Student loan system ‘worst of all worlds’ 2014. http://www.theguardian.com/education/2014/nov/18/higher-education-commission-funding-challenges-sustainability (accessed 18 Nov 2014).

- 27.The Higher Education Commission. Too Good to Fail: The financial sustainability of higher education in England 2014. http://www.policyconnect.org.uk/hec/sites/site_hec/files/report/391/fieldreportdownload/hecommissionreport-toogoodtofail.pdf (accessed 22 Nov 2014).

- 28.Crawford C, Jin WM. Payback time? Student debt and loan repayments: what will the 2012 reforms mean for graduates? IFS Reports (R93). 2014. http://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/7165 (accessed 20 Nov 2014).