Abstract

Objectives

The prognostic utility of serum C reactive protein (CRP) alone in sepsis is controversial. We used decision curve analysis (DCA) to evaluate the clinical usefulness of combining serum CRP levels with the CUBR-65 score in patients with suspected sepsis.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Emergency department (ED) of an urban teaching hospital in Japan.

Participants

Consecutive ED patients over 15 years of age who were admitted to the hospital after having a blood culture taken in the ED between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2012.

Main outcome measures

30-day in-hospital mortality.

Results

Data from 1262 patients were analysed for score evaluation. The 30-day in-hospital mortality was 8.4%. Multivariable analysis showed that serum CRP ≥150 mg/L was an independent predictor of death (adjusted OR 2.0; 95% CI 1.3 to 3.1). We compared the predictive performance of CURB-65 with the performance of a modified CURB-65 with that included CRP (≥150 mg/L) to quantify the clinical usefulness of combining serum CRP with CURB-65. The areas under the receiver operating characteristics curves of CURB-65 and a modified CURB-65 were 0.76 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.80) and 0.77 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.81), respectively. Both models had good calibration for mortality and were useful among threshold probabilities from 0% to 30%. However, while incorporating CRP into CURB-65 yielded a significant category-free net reclassification improvement of 0.387 (95% CI 0.193 to 0.582) and integrated discrimination improvement of 0.015 (95% CI 0.004 to 0.027), DCA showed that CURB-65 and the modified CURB-65 score had comparable net benefits for prediction of mortality.

Conclusions

Measurement of serum CRP added limited clinical usefulness to CURB-65 in predicting mortality in patients with clinically suspected sepsis, regardless of the source.

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE, STATISTICS & RESEARCH METHODS, INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Combining serum C reactive protein (CRP) with CURB-65 gave statistically significant values of net reclassification improvement and integrated discrimination improvement. In contrast, decision curve analysis showed that combining serum CRP with CURB-65 was of only limited clinical usefulness.

The limitations of this study are the possibility of selection bias of the eligible patients and the retrospective nature of the study in a single hospital.

Introduction

Sepsis is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with in-hospital mortality still at 18% or more, according to recent surveys in resource-rich countries.1–3 Early identification of high-risk patients and timely intervention for sepsis are therefore crucial to improving outcomes.

Severity assessment is important in the management of patients, including decision-making regarding choice of treatment and patient disposition. To encourage implementation, a clinical prediction rule must be user-friendly.4 While there are a lot of well-known scoring systems for severity of illness such as the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE), Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) and Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score (MODS), they have too many items to use conveniently in the emergency department (ED).5 In addition, these scores have not been well validated in settings other than the intensive care unit (ICU). CURB-65 is a simple prediction rule originally developed as a prognostic scoring system for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).6 The rule has been well validated in patients with CAP, and CURB-65-guided antibiotic therapy has safely reduced broad-spectrum antibiotic use in this population.7 8 In addition to its utility among patients with CAP, CURB-65 has also been correlated with mortality in patients with suspected sepsis, regardless of the source, and in patients admitted for non-surgical illness.9–11

Serum C reactive protein (CRP) is an acute phase protein often evaluated as a marker of systemic inflammation.12 In Japan, serum CRP levels have been used as a diagnostic and prognostic marker of infection in daily clinical practice and clinical trials of new drugs.13 However, evidence demonstrating its value is insufficient at present for the routine application of serum CRP levels to assess the severity of infection. As a prognostic marker, some have reported that serum CRP on admission is associated with mortality.14 15 However, a systematic review reported conflicting findings, noting that serum CRP levels were not significantly different between a survivor and a non-survivor, suggesting that these levels may have limited value in reflecting the severity of sepsis.12 As a diagnostic marker, the sensitivity and specificity of serum CRP for discriminating bacterial from non-infectious inflammation were only 75% and 67%, respectively, according to a meta-analysis.16 However, while the diagnostic performance of serum CRP alone is limited, serum CRP has been reported to contribute some additional information to a prediction rule involving a patient's symptoms and physical examination in the diagnosis of pneumonia.17 In this respect, the additive prognostic value of serum CRP to an existing severity score is unknown.

Performance of a prediction model has traditionally been evaluated by discrimination and calibration. However, having good discrimination and calibration alone is not sufficient to show that a model would improve decision-making.18 As metrics of reclassification, net reclassification improvement (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) have enjoyed increasing usage in evaluating improvement in prediction models. However, these improvements quantified as NRI and IDI are also not sufficient for evaluating clinical usefulness.19–21 Decision curve analysis (DCA), which was first described by Vickers and Elkin, can be used to incorporate the clinical consequences of a decision into evaluations of diagnostic tests or prediction models.22 To the best of our knowledge, there have been no studies in which DCA is employed to evaluate the clinical usefulness of serum CRP levels and CURB-65 score in patients with suspected sepsis.

Here, our objective was to use DCA to evaluate the clinical usefulness of combining serum CRP levels with the CURB-65 score in patients with suspected sepsis, regardless of the source of infection.

Materials and methods

Study design, setting and patients

We performed a retrospective cohort study at Kyoto City Hospital, an urban teaching hospital with 548 beds in Japan. Consecutive ED patients over 15 years of age admitted to the hospital after having a blood culture taken in the ED between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2012 were included. The doctor’s decision to order a blood culture was used as a surrogate marker for suspected sepsis as in previous studies.11 23 To facilitate data independence, only the index admission was included for patients with multiple admissions during the study period. Patients transferred from another hospital or who had cardiopulmonary arrest on arrival at the hospital were excluded.

Data collection

The following data were extracted from electronic medical records for each patient: age, gender, underlying disease, vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate (RR), and mental confusion and body temperature), laboratory findings (white cell count, platelet count, and blood urea nitrogen and serum CRP levels) and outcome. For vital signs and laboratory data, initial values at the hospital visit were recorded. Blood pressure was measured with a non-invasive cuff. Serum CRP was measured with a latex turbidimetric immunoassay. The items of the CURB-65 score were as follows: mental confusion (present/absent), BUN>7 mmol/L (20 mg/dL), RR ≥30/min, either or both systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≤60 mm Hg, and age ≥65 years.6 Mental confusion was defined as disorientation in a person, place or time or being in a stupor or coma as with a previous study.6

The main outcome measure was 30-day in-hospital mortality. Patients who were discharged or transferred from the hospital within 30 days of admission or who remained in the hospital for more than 30 days were considered alive in this analysis.24

Statistical analysis

First, we validated the CURB-65 model. We graphically assessed the calibration of the CURB-65 model with a calibration plot and tested it with the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. A p value <0.05 indicates a lack of good fit for the model. Regarding the model discrimination, we also computed the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) with a 95% CI using 500 bootstrap resampling.25 The predicted mortalities with 95% CI were calculated by introducing the CURB-65 score as a continuous variable into a univariable logistic regression.

Second, we examined the additional value of serum CRP. We graphically checked whether or not the relationship between the serum CRP level and mortality was linear in the logit with a smoothing curve using a locally weighted least squares (Lowess) regression.26 We conducted logistic regression analysis after adding CRP as a continuous variable to the CURB-65 system. User-friendliness is important for clinical prediction rules and dichotomised test results (normal vs abnormal) are easy to use and interpret. We explored the cut-off point of the serum CRP level for prediction of death in patients with suspected sepsis because the optimal cut-off point was unknown. Serum CRP results were first divided into quartiles and rounded to the nearest 10. Each patient was then assigned to one of four categories corresponding to the CRP quartiles. We assessed the most optimal cut-off point from the AUC. We conducted multivariable logistic regression analysis to adjust predictors of death by introducing prespecified variables: items of CURB-65. We assessed multicollinearity using the variance inflation factor (VIF). VIFs greater than 2.5 may be problematic.27 We also computed the unadjusted OR of covariates using univariable logistic regression to show the influence of adjustment for predictors.

Third, we assessed the model performance of the modified CURB-65 score, which was made by incorporating CRP information into the CURB-65 model, using a calibration plot and Hosmer-Lemeshow test for calibration and AUC for discrimination. Additive information of CRP was evaluated by category-free NRI and IDI.28 With regard to clinical usefulness, we examined the net benefit using DCA.22 Briefly, the method is based on the principle that the relative harms of false positives and false negatives can be expressed in terms of a probability threshold.29 The net benefit is obtained by subtracting the proportion of patients who are false positive from the proportion who are true positive, weighting by the relative harm of a false-positive and a false-negative result. The net benefit of making a decision based on the model can be calculated with the following formula:

|

where n is the total number of patients in the study and Pt is a given threshold probability.22 29 30

With regard to sample size estimation, at least 8–10 events per variable are required for reliable multiple logistic regression analysis,31 32 and 100 events and 100 non-events are required for an external validation study.33 We assumed 30–40 deaths per year among eligible patients, collecting 3 years’ worth of data (90–120 estimated deaths) to appropriately conduct multiple logistic regressions with 11 variables and ensure adequate statistical power.

In terms of handling missing values, we planned to perform a complete case analysis if missing values were below 5%, as such an analysis might then be feasible.34 If missing values were above 5%, we planned to apply an appropriate imputation method.

Data were analysed with R software V.3.0.1 (http://www.r-project.org) and Stata software, V.13 (StataCorp., College Station, Texas, USA) including programmes of Decision Curve Analysis provided by Vickers.35

Results

Patient characteristics

Among 1310 eligible patients over 3 years of study, 108 deaths (8.2% mortality) were recorded. Demographics, underlying diseases, vital signs, laboratory findings and chief diagnosis for admission were presented in table 1. Diagnosis was unclear in 92 patients (7.3%). RRs data were missing for 21 patients, and CRP data were missing for 28 patients (table 3). Overall cases with any missing predictor were 48 in number (3.7%), so we conducted a complete case analysis, leaving 1262 patients (106 deaths, 8.4% mortality) for model evaluation analyses.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics, chief diagnosis for admission and outcome

| Characteristics | n=1262 |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 76 (64–83) |

| Female, n (%) | 560 (44.4) |

| Nursing home resident, n (%) | 37 (2.9) |

| Underlying diseases, n (%) | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 156 (12.4) |

| Congestive heart failure | 101 (8.0) |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 155 (12.3) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 100 (7.9) |

| Chronic liver disease | 77 (6.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 243 (19.3) |

| Malignancy | 222 (17.6) |

| Dementia | 121 (9.6) |

| Autoimmune disorder | 63 (5.0) |

| HIV positive | 3 (0.2) |

| Vital signs | |

| Heart rate (beats/min), median (IQR) | 98 (85–156) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg), median (IQR) | 131 (113–150) |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/min), median (IQR) | 20 (18–24) |

| Body temperature (°C), median (IQR) | 38.1 (37.1–39) |

| Mental confusion, n (%) | 215 (17.0) |

| Laboratory data | |

| White blood cell count (109/L), median (IQR) | 10.5 (7.6–14.6) |

| Platelet count (×109/L), median (IQR) | 196 (150–256) |

| C reactive protein (mg/L), median (IQR) | 72.3 (18.2–149.2) |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mmol/L), median (IQR) | 6.9 (5.0–10.2) |

| Chief diagnosis for admission | |

| Pneumonia | 393 (33.6) |

| Urinary tract infection | 188 (16.1) |

| Skin and Soft tissue infection | 62 (5.3) |

| Acute cholangitis | 47 (4.0) |

| Acute cholecystitis | 33 (2.8) |

| Bowel perforation | 21 (1.8) |

| Other bacterial infection | 150 (12.8) |

| Non-bacterial infection | 103 (8.8) |

| Non-infection | 174 (14.9) |

| Unclear | 92 (7.3) |

| Bacteraemia, n (%) | 210 (16.6) |

| 30-day in-hospital mortality, n (%) | 106 (8.4) |

Table 3.

Adjusted ORs for mortality in multivariable logistic regression analyses

| Variables | Unadjusted ORs (95% CI) | Adjusted ORs* (95% CI) | Missing n, (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRP≥150 mg/L | 2.5 (1.6 to 3.7) | 2.0 (1.3 to 3.1) | 28 (2.1) |

| Age≥65 years | 3.7 (1.9 to 7.3) | 2.3 (1.1 to 4.6) | 0 (0) |

| Mental confusion | 2.9 (1.9 to 4.5) | 2.1 (1.3 to 3.4) | 0 (0) |

| Hypotension (SBP<90 or DBP≤60 mm Hg) | 3.0 (2.0 to 4.5) | 2.1 (1.3 to 3.2) | 0 (0) |

| Tachypnoea (RR≥30/min) | 3.1 (2.0 to 4.8) | 2.4 (1.5 to 3.9) | 21 (1.6) |

| BUN>7 mmol/L | 4.7 (2.9 to 7.6) | 2.7 (1.6 to 4.5) | 0 (0) |

| Overall | – | – | 48 (3.7) |

*Adjusted for items of CURB-65.

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CRP, C reactive protein; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; RR, respiratory rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Validation of CURB-65 in our population

Observed 30-day in-hospital mortalities and predicted mortalities computed by the CURB-65 score are shown in table 4. CURB-65 showed good calibration for mortality, with a Hosmer-Lemeshow test of 4.08 (df=5, p=0.538), indicating good fit. The calibration plot is shown in online supplementary figure S1A. The AUC for CURB-65 was 0.76 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.80; online supplementary figure S2).

Table 4.

Observed mortality, predicted mortality and net benefit in CURB-65 and modified CURB-65*

| CURB-65 score | Observed 30-day mortality, % (death/total) | Predicted mortality† (95% CI) % |

Net benefit‡ | Modified CURB-65 score |

Observed 30-day mortality, % (death/total) | Predicted mortality† (95% CI) % |

Net benefit‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 (0/190) | 1 (0.7 to 2.1) | 0.075 | 0 | 0 (0/152) | 1 (0.6 to 2.0) | 0.075 |

| 1 | 3 (9/334) | 3 (2.0 to 4.2) | 0.061 | 1 | 2 (7/287) | 2 (1.6 to 3.6) | 0.068 |

| 2 | 8 (33/409) | 7 (5.2 to 8.3) | 0.034 | 2 | 6 (23/381) | 5 (4.0 to 6.9) | 0.048 |

| 3 | 13 (34/254) | 14 (11.9 to 17.2) | 0.015 | 3 | 12 (32/265) | 11 (9.2 to 13.3) | 0.024 |

| 4 | 30 (25/84) | 28 (22.5 to 35.2) | 0.004 | 4 | 17 (22/129) | 22 (17.7 to 26.5) | 0.012 |

| 5 | 39 (7/18) | 48 (37.0 to 60.1) | 0 | 5 | 44 (18/41) | 38 (29.9 to 47.8) | 0.005 |

| 6 | 57 (4/7) | 58 (45.2 to 70.4) | 0 |

*The modified CURB-65 score was made by the addition of 1 point if CRP≥150 mg/L.

†Predicted mortality was calculated by introducing CURB-65 and the modified CURB-65 score as a continuous variable into univariable logistic regression.

‡Net benefits were calculated for each predicted mortality as a threshold probability.

CRP, C reactive protein.

Evaluation of CRP as a predictor of mortality

The relationship between the serum CRP level and mortality was almost linear in the logit (see online supplementary figure S3). An unadjusted OR for mortality was 1.05 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.07) per 10 mg/L rise in the serum CRP level. The addition of a continuous serum CRP level to the CURB-65 system revealed that an adjusted OR for mortality was 1.04 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.06) per 10 mg/L increase in concentration. Since the optimal cut-off point was unknown, the serum CRP results were divided into quartiles: the quartile points were 18.2, 72.3 and 149.2 mg/L. Then they were rounded to the nearest 10, and we set interim cut-off points as 20, 70 and 150 mg/L. Observed mortality and unadjusted ORs for mortality of each CRP group are shown in table 2. We repeated regression analyses adding serum CRP as a dichotomised variable with each interim cut-off point. We found 150 mg/L to be the most optimal threshold to dichotomise serum CRP levels.

Table 2.

Observed mortality and unadjusted ORs for mortality stratified by serum CRP categories

| Variables, mg/L | Observed 30-day mortality, % (death/total) | Unadjusted OR* (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| CRP | ||

| 0.1–19.9 | 4.0 (13/326) | 1 (reference) |

| 20–69.9 | 6.6 (19/289) | 1.7 (0.8 to 3.5) |

| 70–149.9 | 8.7 (29/335) | 2.3 (1.2 to 4.5) |

| ≥150 | 14.4 (45/312) | 4.1 (2.1 to 7.7) |

*Calculated by univariable logistic regression.

CRP, C reactive protein.

Adjusted ORs for mortality are shown in table 3. We found no evidence of multicollinearity because the VIFs for predictors in the model in table 3 were less than 1.2. We identified a serum CRP level ≥150 mg/L as an independent predictor of death in patients with clinically suspected sepsis.

Additive information of CRP to CURB-65

Since the adjusted OR (ie, regression coefficient) of CRP was comparable to each item in CURB-65, we made a modified CURB-65 score by adding one point to the CURB-65 score when the serum CRP level was ≥150 mg/L. Table 4 shows observed the 30-day in-hospital mortalities and predicted mortalities stratified by the modified CURB-65 score. The modified CURB-65 also showed good calibration for mortality, with a Hosmer-Lemeshow test of 4.52 (df=6, p=0.607). The calibration plot is shown in online supplementary figure S1B. The AUC for the modified CURB-65 was 0.77 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.81; online supplementary figure S2). By incorporating CRP into CURB-65, event NRI was −0.151 and non-event NRI was 0.538, giving an overall category-free NRI of 0.387 (95% CI 0.193 to 0.582, p<0.0001). Further, IDI for events was 0.014 and IDI for non-events was 0.001, giving an overall IDI of 0.015 (95% CI 0.004 to 0.027, p<0.01). These findings were statistically significant.

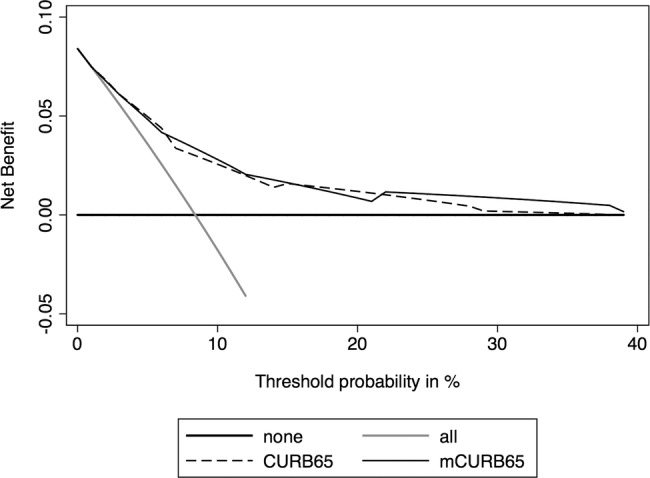

Decision curve analysis

Figure 1 demonstrates the decision curves for CURB-65 and modified CURB-65 to predict 30-day in-hospital mortality in patients with clinically suspected sepsis. Both CURB-65 and the modified CURB-65 are useful between threshold probabilities of 0–30%. However, both curves cross and depict little difference in net benefit. The net benefits at each point of the CURB-65 score and the modified CURB-65 score are shown in table 4. The comparison of discrimination, calibration, reclassification metrics and clinical usefulness between CURB-65 and modified CURB-65 are summarised in table 5.

Figure 1.

Decision curves for the CURB-65 and modified CURB-65 (mCURB-65) to predict 30-day mortality in patients with suspected sepsis. The thick black line is the net benefit of treating no patients, assuming that all would be alive; the thin grey line is the net benefit of treating all patients similarly regardless of their severity, assuming that all would die; the long dashed line is the net benefit of treating patients according to the CURB-65 score; and the thin black line is the net benefit of treating patients based on the modified CURB-65 score.

Table 5.

Comparison of discrimination, calibration, reclassification metrics and clinical usefulness between CURB-65 and modified CURB-65

| CURB-65 | Modified CURB-65 | |

|---|---|---|

| Discrimination | ||

| AUC | 0.76 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.80) | 0.77 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.81) |

| Calibration | ||

| Hosmer-Lemeshow test and calibration plot | Good | Good |

| Reclassification | ||

| Overall category-free NRI | 0.387 (95% CI 0.193 to 0.582, p<0.0001) | |

| Overall IDI | 0.015 (95% CI 0.004 to 0.027, p<0.01) | |

| Clinical usefulness | ||

| NB examined by DCA | Comparable | |

AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; DCA, decision curve analysis; IDI, integrated discrimination improvement; NB, net benefit; NRI, net reclassification improvement.

To assess the robustness of our findings, we repeated DCA with changing the cut-off level of serum CRP as 20 and 70 mg/L, respectively, in sensitivity analyses. Similarly, we found that the additive clinical usefulness of serum CRP was unremarkable.

Discussion

We determined that having high CRP levels was independently associated with high mortality in our population. We also confirmed geographical and domain validation of CURB-65 in our patients, which comprised an external validation in a different geographical area and in a population including a different category of patients from CAP.4

The utility of serum CRP as a prognostic marker has been found to vary.12 In Japan, universal health coverage allows people to consult a doctor soon after they recognise any symptoms, with no particular limitations.36 Given that the secretion of CRP peaks at 36–50 h after inflammatory stimulus,12 the serum CRP level might be useful as a surrogate marker of duration from disease onset to consulting a doctor as well as a marker reflecting the intensity of inflammation. We believe that the association between the serum CRP level and mortality will be more easily identified in countries such as Japan where the population has easy access to hospitals, due to the wide distribution in duration from disease onset to visiting a hospital. Although reclassification metrics such as NRI and IDI were statistically improved on incorporation of the CRP level, the additive clinical usefulness of CRP to CURB-65 was admittedly limited (table 5).

Strengths and limitations of the study

A major strength of this study is our evaluation using DCA. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study which examined the clinical usefulness of serum CRP and the CURB-65 score in septic patients using DCA. DCA can take into account risk threshold, weighting benefits and harms, and is useful in evaluating the clinical utility of a prediction model.21 22 37 For instance, the net benefit of 0.061 at a threshold probability of 3% in the CURB-65 score can be interpreted as meaning that making a decision based on the prediction model, compared to assuming that all patients would be alive, leads to the equivalent of a net 6.1 true-positive results per 100 patients with no corresponding increase in the number of false-positive results (table 4).22 In our population, an 8.4% overall 30-day in-hospital mortality means a maximum net benefit of 0.084, which is calculated if we use a threshold probability of 0%. There are no universally accepted criteria on the patient’s risk threshold for suspected sepsis to make a decision about patient disposition or therapeutic indication. If we extrapolate the data on CAP, low, intermediate and high risk of mortality are considered to be about 1–2%, 8–9% and 20–30%, respectively.6 The ability to make better decisions with serum CRP than without was considered to be unremarkable in this range of risk threshold.

Our study is a type of external validation study with model updating to assess whether the serum CRP level has additive value to CURB-65 or not.4 Another strength of this study might be our sample size with adequate statistical power for an external validation study.33

Several limitations to the present study warrant mention. We cannot rule out the possibility of selection bias, as only inpatients who had a blood culture taken were included. We may therefore have missed patients with infection who did not undergo blood culture in the ED; again, contrarily, some patients without infection were included in the study. However, clinicians must routinely make decisions in the ED despite being unsure as to whether or not a patient is actually infected; we therefore considered it important to evaluate a clinical prediction rule accounting for such clinical uncertainty. Inclusion of patients without infectious diseases, we feel, reflects a real-world scenario. Another limitation is the retrospective nature of the study and the fact that it was conducted in a single hospital. Given the study's retrospective design, patients with a high CRP might have received more intensive therapy than those with a relatively low CRP. Such bias might have lowered the predictive ability of CRP.

Conclusions

While the serum CRP level ≥150 mg/L was found to be associated with high mortality, its additive clinical usefulness to CURB-65 was limited based on DCA. CURB-65 correlated well with 30-day in-hospital mortality in patients with clinically suspected infection, and it was useful among threshold probabilities in the range of 0–30%. Measurement of serum CRP may contribute little to making decisions regarding the management of patients with clinically suspected sepsis.

Footnotes

Contributors: SY had full access to all of the data in the study; he takes responsibility for integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis and wrote the first draft. TS, KT, YT and KS collected and interpreted the data, and drafted the paper. SY, TT, SF, YY and SF supervised the research, interpreted the data and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kyoto University Graduate School and the Faculty of Medicine and Kyoto City Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Kumar G, Kumar N, Taneja A et al. . Nationwide trends of severe sepsis in the 21st century (2000–2007). Chest 2011;140:1223–31. 10.1378/chest.11-0352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaukonen K-M, Bailey M, Suzuki S et al. . Mortality related to severe sepsis and septic shock among critically ill patients in Australia and New Zealand, 2000–2012. JAMA 2014;311:1308–16. 10.1001/jama.2014.2637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujishima S, Gando S, Saitoh D et al. . A multicenter, prospective evaluation of quality of care and mortality in Japan based on the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines. J Infect Chemother 2014;20:115–20. 10.1016/j.jiac.2013.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toll DB, Janssen KJM, Vergouwe Y et al. . Validation, updating and impact of clinical prediction rules: a review. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:1085–94. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calle P, Cerro L, Valencia J et al. . Usefulness of severity scores in patients with suspected infection in the emergency department: a systematic review. J Emerg Med 2012;42:379–91. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R et al. . Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax 2003;58:377–82. 10.1136/thorax.58.5.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chalmers JD, Singanayagam A, Akram AR et al. . Severity assessment tools for predicting mortality in hospitalised patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2010;65:878–83. 10.1136/thx.2009.133280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chalmers JD, Singanayagam A, Akram AR et al. . Safety and efficacy of CURB65-guided antibiotic therapy in community-acquired pneumonia. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011;66:416–23. 10.1093/jac/dkq426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howell MD, Donnino MW, Talmor D et al. . Performance of severity of illness scoring systems in emergency department patients with infection. Acad Emerg Med 2007;14:709–14. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2007.tb01866.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armiñanzas C, Velasco L, Calvo N et al. . CURB-65 as an initial prognostic score in Internal Medicine patients. Eur J Intern Med 2013;24:416–19. 10.1016/j.ejim.2013.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marwick CA, Guthrie B, Pringle JE et al. . Identifying which septic patients have increased mortality risk using severity scores: a cohort study. BMC Anesthes 2014;14:1 10.1186/1471-2253-14-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitaka C. Clinical laboratory differentiation of infectious versus non-infectious systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Clin Chim Acta 2005;351:17–29. 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saito A, Miki F, Oizumi K et al. . Clinical evaluation methods for new antimicrobial agents to treat respiratory infections: Report of the Committee for the Respiratory System, Japan Society of Chemotherapy. J Infect Chemother 1999;5:110–23. 10.1007/s101560050020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chalmers JD, Singanayagam A, Hill AT. C-reactive protein is an independent predictor of severity in community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med 2008;121:219–25. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lobo SMA, Lobo FRM, Bota DP et al. . C-reactive protein levels correlate with mortality and organ failure in critically ill patients. Chest 2003;123:2043–9. 10.1378/chest.123.6.2043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simon L, Gauvin F, Amre DK et al. . Serum procalcitonin and C-reactive protein levels as markers of bacterial infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39:206–17. 10.1086/421997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Vugt SF, Broekhuizen BDL, Lammens C et al. . Use of serum C reactive protein and procalcitonin concentrations in addition to symptoms and signs to predict pneumonia in patients presenting to primary care with acute cough: diagnostic study. BMJ 2013;346:f2450–f50. 10.1136/bmj.f2450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmberg L, Vickers A. Evaluation of prediction models for decision-making: beyond calibration and discrimination. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001491 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steyerberg EW, Vickers AJ, Cook NR et al. . Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology 2010;21:128–38. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c30fb2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leening MJG, Vedder MM, Witteman JCM et al. . Net reclassification improvement: computation, interpretation, and controversies: a literature review and clinician's guide. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:122–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vickers AJ, Pepe M. Does the net reclassification improvement help us evaluate models and markers? Ann Intern Med 2014;160:136–7. 10.7326/M13-2841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vickers AJ, Elkin EB. Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med Decis Making 2006;26:565–74. 10.1177/0272989X06295361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shapiro NI, Wolfe RE, Moore RB et al. . Mortality in Emergency Department Sepsis (MEDS) score: a prospectively derived and validated clinical prediction rule. Crit Care Med 2003;31:670–5. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000054867.01688.D1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graham PL, Cook DA. Prediction of risk of death using 30-day outcome: a practical end point for quality auditing in intensive care. Chest 2004;125:1458–66. 10.1378/chest.125.4.1458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steyerberg EW, Bleeker SE, Moll HA et al. . Internal and external validation of predictive models: a simulation study of bias and precision in small samples. J Clin Epidemiol 2003;56:441–7. 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00047-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hosmer DW. 4 Independent variables in multivariable analysis. Applied Logistic Regression. 3rd edn. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katz MH. Multivariable Analysis: A Practical Guide for Clinicians and Public Health Researchers. 3rd edn. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cook NR, Paynter NP. Performance of reclassification statistics in comparing risk prediction models. Biom J 2011;53:237–58. 10.1002/bimj.201000078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Elkin EB et al. . Extensions to decision curve analysis, a novel method for evaluating diagnostic tests, prediction models and molecular markers. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2008;8:53 10.1186/1472-6947-8-53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vickers AJ. Decision analysis for the evaluation of diagnostic tests, prediction models and molecular markers. Am Stat 2008;62: 314–20. 10.1198/000313008X370302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E et al. . A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 1996;49:1373–9. 10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00236-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cepeda MS, Boston R, Farrar JT et al. . Comparison of logistic regression versus propensity score when the number of events is low and there are multiple confounders. Am J Epidemiol 2003;158:280–7. 10.1093/aje/kwg115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vergouwe Y, Steyerberg EW, Eijkemans MJC et al. . Substantial effective sample sizes were required for external validation studies of predictive logistic regression models. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:475–83. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Royston P, Moons KGM, Altman DG et al. . Prognosis and prognostic research: Developing a prognostic model. BMJ 2009;338:b604 10.1136/bmj.b604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vickers AJ. Decision Curve Analysis. Secondary Decision Curve Analysis 2013. http://www.mskcc.org/research/epidemiology-biostatistics/health-outcomes/decision-curve-analysis-0 (accessed 19 Apr 2014).

- 36.Ikegami N, Yoo B-K, Hashimoto H et al. . Japanese universal health coverage: evolution, achievements, and challenges. Lancet 2011;378:1106–15. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60828-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Localio AR, Goodman S. Beyond the usual prediction accuracy metrics: reporting results for clinical decision making. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:294–5. 10.7326/0003-4819-157-4-201208210-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]