Abstract

Objectives

To assess whether HOUSES (HOUsing-based index of socioeconomic status (SES)) is associated with risk of and mortality after rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Design

We conducted a population-based case–control study which enrolled population-based RA cases and their controls without RA.

Setting

The study was performed in Olmsted County, Minnesota.

Participants

Study participants were all residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, with RA identified using the 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria for RA from 1 January 1988, to 31 December 2007, using the auspices of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. For each patient with RA, one control was randomly selected from Olmsted County residents of similar age and gender without RA.

Primary and secondary outcome measure

The disease status was RA cases and their matched controls in relation to HOUSES as an exposure. As a secondary aim, post-RA mortality among only RA cases was an outcome event. The associations of SES measured by HOUSES with the study outcomes were assessed using logistic regression and Cox models. HOUSES, as a composite index, was formulated based on a summed z-score for housing value, square footage and number of bedrooms and bathrooms.

Results

Of the eligible 604 participants, 418 (69%) were female; the mean age was 56±15.6 years. Lower SES, as measured by HOUSES, was associated with the risk of developing RA (0.5±3.8 for controls vs −0.2±3.1 for RA cases, p=0.003), adjusting for age, gender, calendar year of RA index date, smoking status and BMI. The lowest quartile of HOUSES was significantly associated with increased post-RA mortality compared to higher quartiles of HOUSES (HR 1.74; 95% CI 1.10 to 2.74; p=0.017) in multivariate analysis.

Conclusions

Lower SES, as measured by HOUSES, is associated with increased risk of RA and mortality after RA. HOUSES may be a useful tool for health disparities research concerning rheumatological outcomes when conventional SES measures are unavailable.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, RHEUMATOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The main strength is a population-based study design in a study setting with a self-contained healthcare environment and the availability of medical records for nearly all residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota.

Another strength is the HOUSES (HOUsing-based index of socioeconomic status) as an individual-level SES measure based on an objective measure derived from real property data rather than self-report.

The main limitation includes an inherent limitation as a retrospective study.

Another limitation is a modest sample size and predominantly Caucasian study participants, which might limit the generalisability of our results in other settings.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) causes a significant morbidity and burden to our society affecting about 1.5 million US adults in 2005. The overall prevalence of RA increased from 0.62% in 1995 to 0.72% in 2005.1 Although the literature has shown that genetic and environmental factors determine the risk of RA,2 3 the cause for RA remains unknown.

Socioeconomic status (SES) is correlated with various health outcomes including RA. Indeed, the impact of SES on RA has been widely reported in the USA and other countries.4–6 For example, Pederson, et al7 reported that individual SES measures, including educational level, were shown to be inversely associated with the risk of developing RA among those with the highest educational level compared with those having the lowest level of education (adjusted OR=0.43, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.76, p=0.001). However, the unavailability of individual-level SES measures in commonly used data sources for clinical research has been a significant impediment to advancing health disparities research concerning a broad range of health outcomes including RA.8 Given the rising trends of utilising large-scale administrative data sets for health outcome or service research, the absence of individual-level SES measures might deter the proper interpretation and application of the results. Census (or area)-level SES measures have been used as a proxy measure for individual SES measures.9–11 However, they often result in misclassification bias,12 13 and area-level SES measures might not be a proxy measure for individual-level SES, given the influence of the neighbourhood environment on health outcomes independent of individual SES.14 15

To address the unavailability of individual SES measures in the common data sources, we recently developed and validated a novel individual-level SES measure based on housing features termed HOUSES (ie, HOUsing-based index of SES measure).16 HOUSES is a composite index derived from individual housing features by linking property address information in a clinical data set to enumerated real property data that are available from local government assessors’ offices. Previous studies have shown HOUSES to be significantly associated with health outcomes in children.16–18 However, it has not been applied to research concerning health outcomes in adults.

The main aims of this study were to assess whether HOUSES is associated with risk of RA and mortality after RA. As a comparison, we assessed the relationship between educational levels as a reference SES measure and RA outcomes. To address these study aims, we conducted a population-based case–control study.

Patients and methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Mayo Clinic and the Olmsted County Medical Center.

Study population and settings

Olmsted County, Minnesota, is an excellent setting to conduct a population-based study. The Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP)19–21 links the medical records from all healthcare providers in the county, including Mayo Clinic, Olmsted Medical Center and others for all Olmsted County residents. All diagnoses are electronically indexed and information from every episode of care is contained within detailed patient-based medical records.20

Study design

The study was designed as a population-based case–control study. The primary aim was to determine the association between HOUSES and risk of RA, which was addressed by comparing HOUSES between RA cases and matched controls without a history of RA. The secondary aim was to determine the association between HOUSES and post-RA mortality between the index date of RA and the last follow-up date.

Case ascertainment

Details about the study participants have been reported previously.21 Briefly, all eligible incident RA cases (≥18 years of age) who had fulfilled the 1987 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for RA, between 1 January 1988 and 31 December 2007, were retrospectively identified and assembled using the REP medical records linkage system.19 RA incidence date was defined as the earliest date at which each patient fulfilled ≥4 ACR criteria for RA. Excluded cases are those who were non-Olmsted County, Minnesota, residents during the study time, those who denied authorisation for using medical records for research per Minnesota statute, and those who could not be geocoded to address information and real property data.

Selection of controls

For each patient with RA, one control was randomly selected from all Olmsted County residents of similar age and gender without RA, using the REP medical records linkage system (ie, same source population). Each participant without RA was assigned an index date corresponding to the RA incidence date of the patient with RA.

Mortality after RA

For this secondary outcome, we limited our analysis to only RA cases. All participants were followed until death or 31 December 2008. All death certificates for Olmsted County residents are obtained every year from the county office. In addition, the Mayo Clinic registration office monitors the notice of death in the local newspapers to update the record. Finally, electronic files of death certificates are obtained from the State of Minnesota Department of Vital and Health Statistics.20

Socioeconomic indicators and HOUSES

A demographic questionnaire was used to ascertain self-reported individual-level education status (ie, years of school completed). Educational years were categorised into four groups: less than 12, 12, 13–15 and 16 years or longer. Details about HOUSES have been previously reported.16 Briefly, HOUSES is a composite index that is derived from individual housing features by linking address information at the time of interest (index date of RA or mortality) to enumerated real property data available at most local government assessors’ offices. A factor (construct) that is composed of the number of bedrooms, number of bathrooms, square footage of housing unit and estimated value of housing unit was extracted. HOUSES was formulated by summing a z-score for the number of bedrooms, number of bathrooms, square footage of housing unit and estimated value of housing unit and used as continuous and categorical variables (quartiles): the higher the HOUSES z-score, the higher the SES. It has been recently developed and tested by conducting studies in both Olmsted County, Minnesota, and Jackson County, Missouri. Results for these studies have been reported in previous publications.16–18

Other variables

All factors known to be associated with mortality in RA based on previous work were included in multivariate models for adjustment.21 These factors were ascertained through the review of medical charts and REP by trained nurse abstractors blinded to the original study hypothesis and they include the following: smoking status, rheumatoid factor positivity, history of alcoholism, obesity, cardiovascular disease (including hospitalised or silent myocardial infarction, heart failure, revascularisation, angina or a physician diagnosis of coronary artery disease), renal disease, liver disease, cancer, metastases, dementia, severe extra-articular RA manifestations (ie, pleuritis, pericarditis, Felty's syndrome, RA vasculitis, scleritis, neuropathy or glomerulonephritis), as well as use of glucocorticoids and other RA therapies (ie, methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologicals). The Charlson comorbidity index was assessed using an electronic adaptation developed by Deyo.22 23

Statistical analysis

We first assessed sociodemographic characteristics of participants with and without missing HOUSES. Spearman correlation methods were used to assess the association between HOUSES and educational levels. For the association between HOUSES and risk of RA, we compared sociodemographic and pertinent clinical characteristics of RA cases and their corresponding controls. HOUSES was categorised into quartiles using 604 patients with non-missing data (1st quartile (lowest SES) <−2.0215; 2nd quartile −2.0215 to 0.265; 3rd quartile 0.265–1.81; and 4th quartile (highest SES) ≥1.81)). Logistic regression models were used to determine the association of HOUSES as continuous and categorical (quartiles) variables with risk of RA to adjust for pertinent covariates and confounders. Linearity (or non-linearity) for the association between HOUSES and risk of RA was assessed using smoothing splines.

For the association between HOUSES and mortality after RA as a secondary outcome, overall survival rates after RA among participants with HOUSES in quartiles were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models to allow adjustment for age, gender and calendar year of RA incidence. Estimated survival rates were directly adjusted for the age, gender and calendar year of RA incidence of the RA cohort. The adjusted survival rates were plotted against time since RA incidence is in accordance with quartiles of HOUSES. Association of SES with time to death was evaluated using Cox proportional hazards regression models and summarised with HRs and 95% CIs. Similar to the relationship between HOUSES and risk of RA, non-linearity of the associations between HOUSES and post-RA mortality was examined using smoothing splines. Statistical analyses were performed using the SAS software package V.9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) and R software V.3.0.2 (http://www.r-project.org). All tests were two-sided and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Subject characteristics

The study cohort consisted of 650 RA cases between 1 January 1988, and 31 December 2007. Compared to patients with RA with HOUSES, patients with RA with missing HOUSES were relatively older (mean±SD: 60.0±16.5 years vs 55.5±15.6 years, p=0.042) and had an earlier year of index date (mean±SD: 1993.9±5.8 vs 1999.0±5.4, p<0.001). Otherwise, cases included and those excluded from the study were similar in regard to gender, educational level and marital status. Baseline characteristics of cases and their matched controls are summarised in table 1. Address information was successfully geocoded and HOUSES was formulated for 604 RA cases (93%) and 564 matched controls (87%). The association between HOUSES and educational levels was measured by Spearman correlation coefficient (r=0.40, p<0.001 for controls and r=0.28, p<0.001 for RA cases).

Table 1.

Characteristics of RA cases and their matched controls and the association of HOUSES and each variable with risk of RA

| Controls (N=650) | RA cases (N=650) | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at index date of RA, years, mean (SD) | 55.8 (15.7) | 55.8 (15.7) | 1.00 (0.93 to 1.07)/ 10 year increase | – |

| Gender (female): | 448 (69%) | 448 (69%) | 1.00 (0.79 to 1.27) | – |

| Year of index date, mean (SD) | 1998.6 (5.6) | 1998.6 (5.6) | 1.00 (0.82 to 1.21)/ 10 year increase | 0.97 |

| Race: Caucasian | 618 (96%) | 604 (94%) | 0.59 (0.36 to 0.99) | 0.046 |

| HOUSES | 0.002 | |||

| N | 564 | 604 | 1.06 (1.02 to 1.09)/1 unit | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.5 (3.8) | −0.2 (3.1) | decrease | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.0(−1.9, 2.4) | −0.5 (−2.1, 1.5) | ||

| HOUSES in quartiles | ||||

| Quartile 1 (lowest SES) | 130 (23) | 162 (27) | 1.04 (0.75 to 1.44) | 0.02 |

| Quartile 2 | 128 (23) | 164 (27) | 1.42 (1.02 to 1.98) | |

| Quartile 3 | 151 (27) | 141 (23) | 1.37 (0.98 to 1.91) | |

| Quartile 4 (Highest SES) | 155 (27) | 137 (23) | Referent | |

| Educational level | <0.001 | |||

| Missing | 13 | 22 | ||

| <High school | 60 (9%) | 57 (9%) | 1.92 (1.15 to 3.22) | |

| High school | 192 (30%) | 201 (32%) | 2.13 (1.41 to 3.20) | |

| Technical-school/college | 292 (46%) | 324 (52%) | 2.28 (1.54 to 3.37) | |

| Graduate school | 93 (15%) | 46 (7%) | 1 (reference) | |

| Married in lifetime | 581 (90%) | 590 (91%) | 1.20 (0.82 to 1.74) | 0.35 |

| Body mass index | 0.46 | |||

| Underweight <18.5 kg/m2 | 7 (1%) | 13 (2%) | 1.92 (0.75 to 4.95) | |

| Normal ≥18.5–24.9 kg/m2 | 213 (33%) | 208 (32%) | 1 (reference) | |

| Overweight ≥25–29.9 kg/m2 | 225 (35%) | 212 (33%) | 0.96 (0.73 to 1.26) | |

| Obesity ≥30 kg/m2 | 204 (31%) | 216 (33%) | 1.09 (0.82 to 1.43) | |

| Smoking status | 0.015 | |||

| Current | 104 (16%) | 120 (18%) | 1.36 (1.00 to 1.84) | |

| Former | 194 (30%) | 229 (35%) | 1.41 (1.09 to 1.81) | |

| Never | 352 (54%) | 301 (46%) | 1 (reference) | |

| Pertinent comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 56 (9%) | 61 (9%) | 1.10 (0.75 to 1.62) | 0.62 |

| Congestive heart failure | 19 (3%) | 17 (3%) | 0.89 (0.45 to 1.75) | 0.73 |

| Alcohol misuse | 42 (6%) | 43 (7%) | 1.03 (0.66 to 1.60) | 0.91 |

| Hypertension | 337 (52%) | 412 (63%) | 1.82 (1.42 to 2.34) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 348 (54%) | 373 (57%) | 1.20 (0.95 to 1.51) | 0.14 |

| Charlson comorbidity index† | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 429 (66%) | 259 (40%) | 1 (reference) | |

| 1–2 | 150 (23%) | 281 (43%) | 3.20 (2.46 to 4.17) | |

| ≥3 | 71 (11%) | 110 (17%) | 2.61 (1.79 to 3.18) |

*Adjusted for age, gender and calendar year of RA incidence/index date.

†Excluding rheumatological disorders for comparability.

HOUSES, HOUsing-based index of socioeconomic status; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

HOUSES and risk of RA

HOUSES was significantly lower among RA cases compared to their matched controls (p=0.003; table 1). Age, gender and calendar year of index date were all significantly associated with HOUSES (data not shown). HOUSES was inversely associated with the odds of RA (adjusted OR 1.06/1 unit decrease in HOUSES; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.09; p=0.022), adjusting for age, gender and calendar year of RA incidence/index date. This association persisted after additional adjustment for smoking status and body mass index (adjusted OR 1.06/1 unit decrease in HOUSES; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.09; p=0.003) (data now shown). Non-linearity for the association between HOUSES and risk of RA was examined using smoothing splines. Non-linearity component was not statistically significant (p=0.38). When we examined the association of HOUSES in quartiles with odds of RA, we observed similar findings. Controlling for the same variables as above, HOUSES in quartiles was inversely associated with the risk of RA (p value for trend=0.02, table 1). As a reference SES measure, when we examined the association between educational levels and odds of RA, we found that educational levels as a discrete variable was similarly associated with odds of RA, adjusting for age, gender, calendar year of RA, smoking status and body mass index (p=0.002) (data not shown). Controlling for the same variables, educational levels in categorical variables were associated with the risk of RA (table 1).

HOUSES and mortality after RA

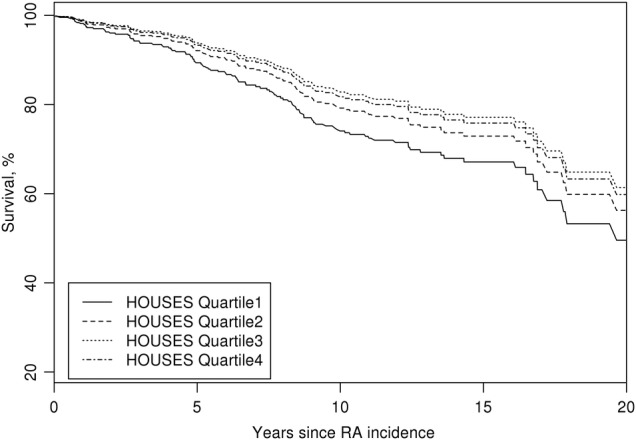

During the follow-up period, 109 of the patients with RA with available HOUSES had died. The cumulative mortality rates at 20 years following RA were 50% (95% CI (32% to 69%), 44% (25% to 62%), 39% (20% to 57%) and 40% (22% to 59%) for patients in the first (lowest SES), second, third and fourth quartiles (highest SES) of HOUSES, respectively, adjusted for age, gender and calendar year. The results are summarised in figure 1. Overall comparisons of the four quartiles of HOUSES summarised in table 2 only approached statistical significance. However, when patients in the lowest quartile of HOUSES (≤−2.1) were compared with patients with higher HOUSES values (the other 3 quartiles combined), there was a significant association for the lowest quartile of HOUSES with an increased risk of mortality (HR 1.58; 95% CI 1.05 to 2.36; p=0.027) adjusted for age, gender and calendar year of RA incidence. This association remained significant following an additional adjustment for all factors (ie, comorbid conditions, RA therapies, smoking history and BMI) associated with post-RA mortality listed in the Method section (HR; 1.74; 95% CI 1.10 to 2.74; p=0.017). None of the risk factors, such as RA therapy or extra-articular manifestations of RA, accounted for the association of HOUSES with mortality after RA. HOUSES, as a continuous variable, was not linearly associated with the outcome of mortality in patients with RA (HR 1.03/1 unit decrease of HOUSES, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.11, p=0.37) following adjustment to age, gender and calendar year of RA incidence/index date. A significant non-linear (inverse) association between HOUSES and post-RA mortality was found after adjusting for the same variables (p=0.010) (data not shown). This finding is consistent with the significant findings by quartiles. No significant association between educational level and mortality after RA was found (p=0.98, table 2).

Figure 1.

Estimated survival curves adjusted for age, gender and calendar year of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) incidence according to quartiles of HOUsing-based index of socioeconomic status (HOUSES) (the numbers in parentheses are the range of HOUSES for each group).

Table 2.

Association of HOUSES and other variables with post-RA mortality during the study period

| Adjusted HRs* (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) at RA incidence date | 2.76 (2.35 to 3.22)/10 year increase | <0.001 |

| Gender: male | 1.13 (0.78 to 1.64) | 0.50 |

| Year of RA incidence date | 0.90 (0.57 to 1.43) | 0.67 |

| Race: Caucasian | 0.64 (0.28 to 1.49) | 0.30 |

| HOUSES as a continuous variable | 1.03 (0.96 to 1.11) | 0.37 |

| HOUSES in quartiles | ||

| Quartile 1 (lowest SES) | 1.73 (0.91 to 3.30) | 0.09 |

| Quartile 2 | 1.21 (0.63 to 2.35) | |

| Quartile 3 | 0.92 (0.44 to 1.91) | |

| Quartile 4 (highest SES) | 1 (reference) | |

| Educational level | ||

| <High school | 1.25 (0.47 to 3.32) | 0.98 |

| High school | 1.21 (0.48 to 3.07) | |

| Technical school/college | 1.21 (0.48 to 3.06) | |

| Graduate school | 1 (reference) | |

| Married in lifetime (vs never married) | 0.67 (0.34 to 1.36) | 0.27 |

| Body mass index | 0.020 | |

| Underweight <18.5 kg/m2 | 2.84 (1.30 to 6.20) | |

| Normal ≥18.5–24.9 kg/m2 | 1 (reference) | |

| Overweight ≥25–29.9 kg/m2 | 0.89 (0.59 to 1.34) | |

| Obesity ≥30 kg/m2 | 0.78 (0.48 to 1.27) | |

| Smoking status | 0.001 | |

| Current | 2.48 (1.51 to 4.05) | |

| Former | 1.42 (0.94 to 2162) | |

| Never | 1 (reference) | |

| Charlson comorbidity Index† | <0.001 | |

| 0 | 1 (reference) | |

| 1–2 | 1.65 (1.02 to 2.68) | |

| ≥3 | 2.89 (1.66 to 5.02) |

*Adjusted for age, gender and calendar year of RA incidence/index date.

†Excluding rheumatological disorders.

HOUSES, HOUsing-based index of socioeconomic status; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Discussion

Our study results showed that lower SES, as measured by HOUSES, was independently associated with increased risk of RA and mortality after RA. However, educational levels as a reference SES measure were only associated with the risk of RA.

As we previously reported, HOUSES and educational levels of participants showed a moderate correlation (r=0.28–0.40), and this finding is consistent with the literature (r=0.33 for education and income, r=0.40 for occupation and income, and r=0.61 for occupation and education).8 16 These results not only confirm our previous study findings but also suggest that HOUSES might measure a different construct of SES, which is not captured by other SES measures such as education levels. Despite the moderate correlation with educational levels, HOUSES showed a significant inverse association with risk of RA both as a continuous variable and as a categorical variable (quartiles). This association persisted after adjustment for pertinent covariates and confounders. Educational levels were similarly associated with risk of RA. There was a linear inverse relationship between HOUSES and risk of RA based on linearity testing using a smoothing spline, suggesting no specific cut-offs or threshold for the impact of HOUSES on risk of RA.

For the association between HOUSES and post-RA mortality during the follow-up period, there was no significant linear relationship, but a significant non-linear relationship between HOUSES and post-RA mortality suggesting an inverse association was found. Although overall comparisons among HOUSES in quartiles only approached statistical significance, when we compared post-RA mortality between the lowest quartile and the rest, we found a significant association of HOUSES with post-RA mortality after adjusting all potential factors associated with outcomes of RA (HR; 1.74 for the lowest quartile of HOUSES; 95% CI 1.10 to 2.74; p=0.017). However, educational levels were not associated with post-RA mortality. Therefore, despite the moderate concordance between HOUSES and educational levels, HOUSES is a more suitable SES measure in predicting post-RA mortality than educational levels. Also, HOUSES was originally developed from a sample of young families with children in Olmsted County, Minnesota, and Jackson County, Missouri. Given the mean age of study participants, the present study findings suggest that HOUSES is potentially generalisable to adult populations highlighting external validity in terms of age of study participants.

Previous studies have shown a similar inverse association of SES with risk of developing RA and post-RA health outcomes. For example, Bengtsson et al24 reported that high SES, defined as individuals with high education and less manual work, was associated with a decreased risk of developing RA. In addition, in a prospective study conducted in the West of Scotland which evaluated 200 patients with RA, Maiden et al25 reported that the 12-year mortality percentage was higher in deprived areas compared to more affluent areas, according to the level of male unemployment, overcrowding, car ownership and distribution of social class within the area's population (61% vs 36% death percentage).

The mechanisms underlying the association of HOUSES with risk of and mortality after RA have not been fully elucidated and need to be studied in the future, using the suggested framework for health disparities (genetic model, fundamental pathway model and gene-environmental interaction model).26 To reduce the gap in differential mortality after RA among individuals with different SES, clinicians or healthcare systems need to consider their preventive and therapeutic strategies in the patients’SES. In understanding and addressing heterogeneity of outcomes among patients with RA, in addition to immunogenetic factors, one's SES may provide additional and important information; in this respect, HOUSES index may be helpful in clinical research, which identifies patients with a mismatch between medical needs (greater medical needs) and access to resources (decreased availability of resources). Also, research efforts should be made to determine the extent to which SES modifies the effect of RA therapies on its outcomes.

Baldassari et al27 recently reported that home ownership is associated with a lower risk of significant clinical activity of RA. In our study, home ownership was not categorised into the same factor as housing features resulting in HOUSES in our original study. Owing to a high home ownership rate in Olmsted County (∼75% or so), it might not necessarily measure the same construct underlying the current HOUSES (primarily housing size and features).

Our study has several limitations. Although the sample size was relatively modest in this study, we were able to address the study aims. Another limitation is that the study sample participants were predominantly Caucasian, which might limit the generalisability of our results in other settings. Moreover, despite excluding RA cases with missing HOUSES, due to the retrospective nature of this study, a comparison of excluded cases with those with non-missing HOUSES has shown that they have similar baseline characteristics.

The main strength of this study is the population-based study design. Another important strength is the epidemiological advantages of the study setting including a self-contained healthcare environment with availability of comprehensive medical records of nearly all residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, under the auspices of REP. Also, HOUSES has the advantage of being an individual-level SES measure that consists of available objective measures based on real property data rather than self-reported subjective measures. In addition, housing data are publicly available and are maintained and updated because they are the basis of real property assessment and taxation. Also, given that the median duration of residence in the USA was only 4.7 and 1.9 years for people aged 25–34,28 HOUSES can capture changes in individual SES over time.29

In conclusion, while educational levels were only associated with the risk of RA, lower SES, as measured by HOUSES, is associated with both increased risk of RA and mortality after RA. HOUSES may be a useful tool for epidemiological research concerning rheumatological disease outcomes among adults when conventional SES measures are unavailable in commonly used data sets.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Chung Wi for his comments and suggestions and Denise Chase for administrative assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: HG participated in the study design and interpretation of results, drafted the manuscript and approved the manuscript; CSC participated in the study design, performed the data analysis, interpreted the results and reviewed and approved the manuscript; JR-W participated in the study design and data collection, interpreted the results and reviewed and approved the manuscript; EK participated in the study design and data collection, and reviewed and approved the manuscript; SEG, YJJ participated in the study design and interpretation of results, and reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Funding: The study was supported by the Office of Health Disparities Research Award from Mayo Foundation. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) of the National Institute of Health under Award Number R01AR046849 and the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG034676. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Boards of the Mayo Clinic and the Olmsted County Medical Center.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Kremers HM et al. . Is the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis rising?: results from Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1955–2007. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:1576–82. 10.1002/art.27425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacGregor AJ, Snieder H, Rigby AS et al. . Characterizing the quantitative genetic contribution to rheumatoid arthritis using data from twins. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:30–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoovestol RA, Mikuls TR. Environmental exposures and rheumatoid arthritis risk. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2011;13:431–9. 10.1007/s11926-011-0203-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massardo L, Pons-Estel BA, Wojdyla D et al. . Early rheumatoid arthritis in Latin America: low socioeconomic status related to high disease activity at baseline. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:1135–43. 10.1002/acr.21680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parks CG, D'Aloisio AA, DeRoo LA et al. . Childhood socioeconomic factors and perinatal characteristics influence development of rheumatoid arthritis in adulthood. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:350–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marra CA, Lynd LD, Esdaile JM et al. . The impact of low family income on self-reported health outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis within a publicly funded health-care environment. Rheumatology 2004;43:1390–7. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pedersen M, Jacobsen S, Klarlund M et al. . Socioeconomic status and risk of rheumatoid arthritis: a Danish case-control study. J Rheumatol 2006;33:1069–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liberatos P, Link BG, Kelsey JL. The measurement of social class in epidemiology. Epidemiol Rev 1988;10:87–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon AE, Lukacs SL, Mendola P. Emergency department laboratory evaluations of fever without source in children aged 3 to 36 months. Pediatrics 2011;128:e1368–75. 10.1542/peds.2010-3855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster SB, Paul ME, Kozinetz CA et al. . Prevalence of asthma in children and young adults with HIV infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;119:750–2. 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lang DM, Polansky M, Sherman MS. Hospitalizations for asthma in an urban population: 1995–1999. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2009;103:128–33. 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60165-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pardo-Crespo MR, Narla NP, Williams AR et al. . Comparison of individual-level versus area-level socioeconomic measures in assessing health outcomes of children in Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Epidemiol Community Health 2013;67:305–10. 10.1136/jech-2012-201742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marra CA, Lynd LD, Harvard SS et al. . Agreement between aggregate and individual-level measures of income and education: a comparison across three patient groups. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:69 10.1186/1472-6963-11-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Juhn YJ, Sauver JS, Katusic S et al. . The influence of neighborhood environment on the incidence of childhood asthma: a multilevel approach. Soc Sci Med 2005;60:2453–64. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim D, Diez Roux AV, Kiefe CI et al. . Do neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation and low social cohesion predict coronary calcification?: the CARDIA study. Am J Epidemiol 2010;172:288–98. 10.1093/aje/kwq098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juhn YJ, Beebe TJ, Finnie DM et al. . Development and initial testing of a new socioeconomic status measure based on housing data. J Urban Health 2011;88:933–44. 10.1007/s11524-011-9572-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butterfield MC, Williams AR, Beebe T et al. . A two-county comparison of the HOUSES index on predicting self-rated health. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:254–9. 10.1136/jech.2008.084723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson MD, Urm SH, Jung JA et al. . Housing data-based socioeconomic index and risk of invasive pneumococcal disease: an exploratory study. Epidemiol Infect 2013;141:880–7. 10.1017/S0950268812001252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA et al. . The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1988;31:315–24. 10.1002/art.1780310302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melton LJ., III History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc 1996;71:266–74. 10.4065/71.3.266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Nicola PJ et al. . The influence of rheumatoid arthritis disease characteristics on heart failure. J Rheumatol 2011;38:1601–6. 10.3899/jrheum.100979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL et al. . A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:613–19. 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bengtsson C, Nordmark B, Klareskog L et al. . Socioeconomic status and the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis: results from the Swedish EIRA study. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:1588–94. 10.1136/ard.2004.031666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maiden N, Capell HA, Madhok R et al. . Does social disadvantage contribute to the excess mortality in rheumatoid arthritis patients? Ann Rheum Dis 1999;58:525–9. 10.1136/ard.58.9.525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diez Roux AV. Conceptual approaches to the study of health disparities. Annu Rev Public Health 2012;33:41–58. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baldassari AR, Cleveland RJ, Jonas BL et al. . Socioeconomic disparities in the health of African Americans with rheumatoid arthritis from the Southeastern United States. Arthritis Care Res 2014;66:1808–17. 10.1002/acr.22351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schachter JP, Kuenzi JJ. Seasonality of moves and the duration and tenure of residence: 1996. The US Bureau of Census, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dunn JR. Housing and health inequalities: review and prospects for research. Housing Stud 2000;15:341–66. 10.1080/02673030050009221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]