Abstract

Objectives

Policymakers face many decisions when considering public financing for health, including the kind of health interventions to include in a publically financed package. The consequences of these choices will influence health outcomes as well as the financial risk protection provided to different segments of the population. The purpose of this study is to illustrate the size and distribution of benefits due to treatment and prevention of diarrhoea (ie, rotavirus vaccination).

Methods

We use an economic model to examine the impacts of universal public finance (UPF) of diarrhoeal treatment alone, as opposed to diarrhoeal treatment along with rotavirus vaccination in Ethiopia using extended cost-effectiveness analysis (ECEA). ECEA allows us to measure the health gains and financial risk protection provided by these interventions for each wealth quintile. Our model compares a baseline situation with diarrhoeal treatment seeking of 32% (overall) and no rotavirus vaccination, to a situation where UPF increases treatment seeking by 20 percentage points for each quintile and rotavirus vaccination reaches DTP (diphteria, pertussis, tetanus) 2 levels for each quintile (overall rate of 52%). We calculate deaths averted, private expenditures averted and costs incurred by the government under the baseline situation and with UPF.

Results

We find that diarrhoeal treatment paired with rotavirus vaccination is more cost effective than diarrhoeal treatment alone for the metrics we examine in this paper (deaths and private expenditures averted). Per US$1 million invested, diarrhoeal treatment saves 44 lives and averts US$115 000 in private expenditures. For the same investment, diarrhoeal treatment and rotavirus vaccination save 61 lives and avert US$150 000 in private expenditures. The health benefits of these interventions tend to benefit the poor, while the financial benefits favour the better-off.

Conclusions

Policymakers should consider multiple benefit streams as well as their scale and incidence when considering public finance of health interventions.

Keywords: HEALTH ECONOMICS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This paper extends traditional cost-effectiveness analysis to examine the health and financial implications of publically financed health interventions by wealth quintile.

This paper provides insight into the potential consequences of a high-profile policy issue—universal health coverage.

This paper uses extended cost-effectiveness analysis (ECEA) methods.

This is a static model rather than a dynamic model; hence, herd immunity was not included.

This analysis does not address the needs of households which do not seek care from a health facility or provider.

Introduction

Universal health coverage (UHC) continues to receive considerable attention from the global health community.1–6 Powerful health advocates publically support UHC, including WHO Director General Margaret Chan who stated that “universal health coverage [is] the single most powerful concept that public health has to offer.”6 While substantial variation is a hallmark of the UHC movement, UHC is generally viewed along three dimensions: who is covered, what services are covered, and the proportion of the costs that are covered.1 As countries move closer to UHC, potential benefits include improved health outcomes and improved financial risk protection (FRP). Unfortunately, little evidence is available to allow policymakers to examine and compare the potential benefits of UHC in these disparate realms. Recent work provides a tool, extended cost-effectiveness analysis (ECEA), to gain a more complete understanding of the health and financial benefits associated with different health interventions.7 ECEA combines traditional cost-effectiveness with a quantification of the benefits associated with the reduction in risk exposure.7–10 This tool allows policymakers to make decisions based on the joint benefits and tradeoffs associated with different health interventions. The current paper extends previous work through the examination of two child health interventions (diarrhoeal treatment and rotavirus vaccination) in Ethiopia.8 This paper compares the benefits of publically financed diarrhoeal treatment alone, as well as publically financed diarrhoeal treatment and rotavirus vaccination in the health and FRP domains. We selected these interventions as they represent efficacious prevention and treatment options. While diarrhoea has many causes, it is believed that rotavirus is the cause of 27% of severe diarrhoeal episodes and deaths in the African region.11 The efficacy of vaccination and treatment varies by setting, but in contexts such as Ethiopia, vaccination has an efficacy of approximately 50% while treatment efficacy nears 95%.12 13 This analysis also examines these benefits by wealth quintile, so policymakers and the engaged public can better understand how each intervention affects different segments of the population—a critical element of publically financed healthcare.

Ethiopia is a fitting country in which to base this analysis. Ethiopia has a population of approximately 92 million and is sub-Saharan Africa's second largest country.14 It is a low-income country with a per capita gross domestic product (GDP) of US$357, a growth rate of 7–8%, and approximately 30% of its population living under the poverty line.14 Approximately one-third of health expenditures are financed out-of-pocket (OOP) in Ethiopia.15 Despite formidable challenges, Ethiopia has made substantial progress in reducing the under-five mortality rate from 204 deaths per 1000 live births in 1990 to 68 in 2012, achieving the Millennium Development Goal 4 3 years early.16 However, there is still substantial need for child health interventions. In 2012, approximately 250 000 Ethiopian children died from preventable causes and treatable diseases before reaching their fifth birthday. Apart from neonatal causes, the two major killers of children in Ethiopia are acute respiratory infections and diarrhoea.17 Even with substantial improvement in the last two decades, coverage of child healthcare services remains very low. According to Ethiopia's 2011 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), coverage of Pentavalent 3 (the 3rd dose of diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, Haemophilus influenzae type b and hepatitis B vaccine), and care seeking for diarrhoea were 35% and 32%, respectively.18 Additionally, inequities in child mortality and access to care, between urban and rural dwellers and across wealth quintiles, remain large. Infant mortality is 29% higher in rural areas (76 deaths per 1000 live births) than in urban areas (59 deaths per 1000 live births). The urban–rural difference is even more pronounced in the case of under-five mortalities (83 and 114 deaths per 1000 live births in urban and rural areas, respectively). Furthermore, wide regional variations were observed in infant and under-five mortality. Under-five mortality rates range from a low of 53 per 1000 live births in Addis Ababa to a high of 169 per 1000 live births in Benishangul-Gumuz in the western part of the country. Despite increased risk of diarrhoeal illnesses among children from the lowest wealth quintile, children from the wealthiest quintiles were considerably more likely to receive care from a health facility or provider.18

The objective of this study is to provide evidence-based information on the expected health and FRP outcomes of various diarrhoea-related interventions. This will allow policymakers to consider both health and financial outcomes when making resource allocation decisions regarding these interventions.

Methods

In this paper, we analyse the implications of universal public finance (UPF)—the government pays for care irrespective of who is receiving it—of diarrhoeal treatment as well as the combination of both rotavirus vaccination and diarrhoeal treatment. Diarrhoeal treatment (which includes ORS (oral rehydration salts) and zinc delivered in an outpatient setting or hospitalisation) and rotavirus vaccination are complementary investments and share similarities in the modelling framework. For purposes of clarity, we discuss the methodology and calculations for diarrhoeal treatment and rotavirus vaccination as though they were standalone interventions. However, our analysis considers the cases of (1) diarrhoeal treatment and (2) rotavirus vaccination and diarrhoeal treatment. We analyse the second case by examining rotavirus vaccination and then reconsidering the effect of diarrhoeal treatment with reduced diarrhoeal incidence and deaths. In our results, we report on the effect of diarrhoeal treatment, and the joint effect of the two interventions. Note that our core analysis does not directly compare the impact of rotavirus vaccination (alone) to diarrhoeal treatment. While this is an interesting comparison, policymakers may consider rotavirus vaccination as a realistic alternative to diarrhoeal treatment. This economically rational decision may be medically inappropriate. As such, we compare treatment alone to prevention and treatment together. The interested reader will find select results of the vaccination-only intervention in the discussion.

In this analysis, we examine the health outcomes (deaths averted) and the financial implications of these interventions. In terms of the financial implications, we include private expenditures averted and the increased costs to the government. This paper takes the under-five population of Ethiopia as the beneficiary population for these interventions.

Mortality distribution

Diarrhoea accounts for approximately 10–15% of all under-five deaths in Ethiopia.11 17 19Across Africa, rotavirus is responsible for 27% of all deaths owing to diarrhoea, a proportion that we apply to Ethiopia.11

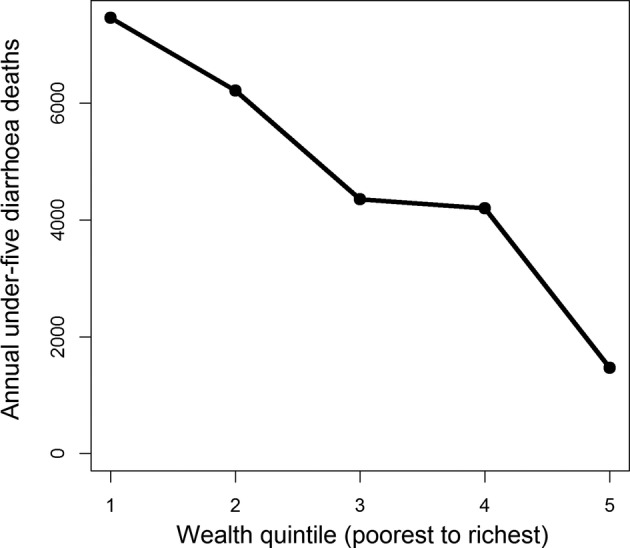

To estimate deaths from diarrhoea and rotavirus by wealth quintile, we begin with the under-five deaths caused by diarrhoea in Ethiopia.11 We then distribute these deaths across the wealth distribution by applying the methodology outlined in Rheingans et al's study.20 Rheingans et al calculate the risk of rotavirus mortality per 1000 births for each quintile by using three proxy measures. One proxy represents access to care (the postneonatal mortality rate), and two represent higher physical susceptibility as measured by weight for age Z scores. Each of these proxies were then used to estimate the quintile share of rotavirus mortality. In the absence of clear evidence as to which proxy best represents the quintile share, an average value was calculated from all three proxies. Rheingans et al report rotavirus deaths per 1000 births. We then adjust their methodology to account for the percentage of women currently pregnant, and the percentage of under-fives with diarrhoea in each wealth quintile as reported in the Ethiopian DHS.18 This establishes a baseline number of deaths owing to diarrhoea, by wealth quintile, and figure 1 presents the resulting distribution of mortality from diarrhoea across the different wealth quintiles.

Figure 1.

Estimated under-five mortality for diarrhoea across wealth quintiles in Ethiopia.

Diarrhoeal treatment: deaths averted

To determine the number of deaths averted by UPF in the diarrhoeal treatment, we assume a 20-percentage point increase in treatment seeking above the level reported for each wealth quintile in the 2011 Ethiopian DHS.18 For example, the overall treatment seeking rate for diarrhoea is 31.8%, though it ranges from just over 20% in the lowest quintile to just over 50% in the highest quintile. After UPF, the overall rate is 51.8% with the 20-percentage point increase in treatment seeking applied to each quintile. We also assume that diarrhoeal treatment is 93% effective in preventing deaths from diarrhoea.12 Deaths averted by wealth quintile are the product of the baseline number of diarrhoeal deaths, the increase in treatment coverage, and the effectiveness of treatment.

Rotavirus vaccine: deaths averted

After determining the baseline number of diarrhoeal deaths by wealth quintile as described above, we attribute 27% of diarrhoeal deaths to rotavirus.11 This yields the number of rotavirus-attributable deaths by wealth quintile. To calculate coverage increases as a result of UPF of rotavirus vaccination, we begin with a baseline of no rotavirus vaccination. UPF of the vaccine is assumed to increase coverage to the level achieved by the second dose of the diphteria, pertussis, tetanus (DPT) vaccine, an achievable level of coverage in the local health system (table 1). While estimates of vaccine efficacy vary in sub-Saharan Africa and by strain, we use an effectiveness of 49% for all strains, and assume that it prevents visits to the health facilities as well as mortality.8 20 21 Specifically, to estimate number of rotavirus deaths averted, the model follows the under-five Ethiopian birth cohort, and rotavirus deaths averted are the product of baseline rotavirus deaths, vaccine coverage and vaccine effectiveness.8 The approach is static and, therefore, is not able to capture epidemiological changes such as herd immunity, which has only been documented in a few countries.21–23

Table 1.

Parameters used for the economic evaluation of UPF for rotavirus vaccination and diarrhoeal treatment in Ethiopia

| Parameter | Value | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Epidemiology | ||

| Under-5 deaths due to diarrhoea in 2011 | 23 700 | Walker et al11 |

| Proportion of under-5 diarrhoeal deaths attributed to rotavirus | 27% | Walker et al11 |

| Percentage of mortality, from poorest to richest (wealth quintile 1–5) | 31, 26, 18, 18, 6 | Authors’ calculations based on EDHS18 Rheingans et al;20 see online supplemental material |

| Interventions | ||

| Diarrhoeal treatment effectiveness | 0.93 | Munos et al12 |

| Rotavirus vaccine effectiveness (per 2-dose course) | 0.49 | Madhi et al*13 |

| Coverage of diarrhoeal treatment, from poorest to richest (wealth quintile 1–5), before UPF Coverage of diarrhoeal treatment, from poorest to richest (wealth quintile 1–5), after UPF |

22%; 25%; 35%; 33%; 53% 42%; 45%; 55%; 53%; 73% |

EDHS18 |

| Coverage of vaccine (DTP2 rates), from poorest to richest (wealth quintile 1–5), before UPF Coverage of vaccine (DTP2 rates), from poorest to richest (wealth quintile 1–5), after UPF |

0%; 0%; 0%; 0%; 0% 42%; 45%; 47%; 57%; 78% |

EDHS18 |

| Costs (2011) | ||

| Hospitalisation costs for diarrhoea | US$49 | Stack et al;24 WHO-CHOICE25 |

| Outpatient clinic visit costs for diarrhoea | US$9 | Stack et al;24 WHO-CHOICE25 |

| Transportation costs for inpatient visit | US$8 | Authors’ calculations based on;14 26 see online supplementary material |

| Transportation costs for outpatient visit | US$4 | Authors’ calculations based on;14 26 see online supplementary material |

| Probability of hospitalisation for diarrhoea, from poorest to richest (wealth quintile 1–5) | 0.02; 0.02; 0.01; 0.02; 0.01 | Authors’ calculations based on EDHS18 and Lamberti et al;27 see online supplementary material |

| Probability of outpatient visit for diarrhoea, from poorest to richest (wealth quintile 1–5) | 0.22; 0.25; 0.35; 0.33; 0.53 | EDHS18 |

| Vaccine price (per vial, 2 doses needed) | GAVI28 | |

| Base case | US$1.0 | |

| No GAVI subsidy | US$2.5 | |

| With GAVI subsidy | US$0.2 | |

| Vaccination system cost (per vial, 2 doses needed) | US$0.5 | Griffiths et al 29 |

| Ethiopia's gross domestic product per capita | US$360 | World Bank14 |

*Based on data from Malawi.

DPT, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus; UPF, universal public finance.

Diarrhoeal treatment: private expenditure averted

In addition to averting deaths, publically financed diarrhoeal treatment can also avert private medical expenditures. Private expenditures averted are based on the number of diarrhoeal episodes, the probability of seeking treatment (either inpatient or outpatient), inpatient and outpatient treatment costs (including transportation), and the percentage of total health expenditure paid OOP. In calculating private expenditures averted, we assume that UPF averts the copays (OOP expenditure) paid by individuals seeking treatment for diarrhoea. In this analysis, OOP expenditures include formal or informal copays as well as other drug costs incurred by the household prior to receiving formal care. Transportation costs are considered separately. For a small group of individuals (those who are newly encouraged to seek treatment as a result of the publically financed intervention), public finance leads to new (transportation) costs which are not averted through UPF.

Rotavirus vaccine: private expenditure averted

Private expenditures averted through publically financed rotavirus vaccination are calculated differently than for diarrhoeal treatment, because vaccination prevents a subset of the diarrhoeal cases and their related expenditures. That is, the vaccine averts diarrhoeal expenditures for cases that did not occur but would have, in the absence of the vaccine. Private expenditures averted depends on number of cases of rotavirus (a subset of total diarrhoeal cases), vaccine coverage, the effectiveness of the vaccine, the probability of seeking either inpatient or outpatient care in the absence of the vaccine, and the cost of inpatient and outpatient care including transportation costs.

Diarrhoeal treatment: cost to government

The government incurs increased costs by providing public finance for diarrhoeal treatment. For those who already seek treatment at baseline, the increased cost is the copay for treatment (34%) that the government would assume. The total cost for this population is influenced by the number of episodes, the probability of seeking treatment, the relative distribution between inpatient and outpatient treatment, and the costs of each treatment option. Treatment costs are based on international estimates rather than an Ethiopia-specific unit cost analysis. These cost estimates include both the cost of the visit and medications (ie, ORS, zinc). The same factors are important in estimating costs for those newly crowded into diarrhoeal treatment through UPF. However, for the 20-percentage point increase in treatment seeking, the government's cost increase includes the total cost of care rather than only the 34% copay.

Rotavirus vaccine: cost to government

Government costs for UPF of the rotavirus vaccine also differ from the case of diarrhoeal treatment. Costs for the rotavirus vaccine are based on the size of the vaccinated population, vaccine coverage (assuming DTP2 rates), the costs of the vaccine, and the associated costs of delivery. Because the rotavirus vaccine also averts future costs of rotavirus treatment, the averted treatment costs are subtracted from the cost of delivering the vaccine.

Table 1 provides a summary of the parameters and sources used in the analysis described above. Additional details on the calculations discussed above can be found in online supplementary table S1. All analyses were carried out using the R statistical software (http://www.r-project.org). Additionally, the model structure (decision tree) is available for illustrative purposes in online supplementary figure S1.

Results

At a summary level, the interventions described above lead to the following outcomes for the Ethiopian under-five cohort. On an annual basis, UPF for diarrhoeal treatment averts 4400 deaths and US$12 million of household private expenditures at the cost of approximately US$100 million to the government. Rotavirus vaccination and diarrhoeal treatment together avert 5600 deaths and US$13.5 million in private expenditures at a net cost of US$93 million to the government (gross government expenditure for rotavirus vaccination and diarrhoeal treatment is approximately US$102 million). Without factoring in the benefits of averting private health expenditures, diarrhoeal treatment saves lives at a cost of approximately US$23 000 to the government, whereas, rotavirus vaccination and diarrhoeal treatment jointly avert deaths at an approximate cost of US$18 000.

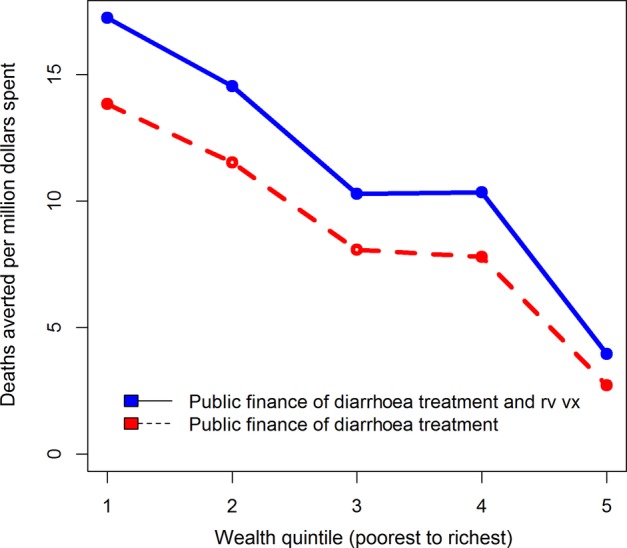

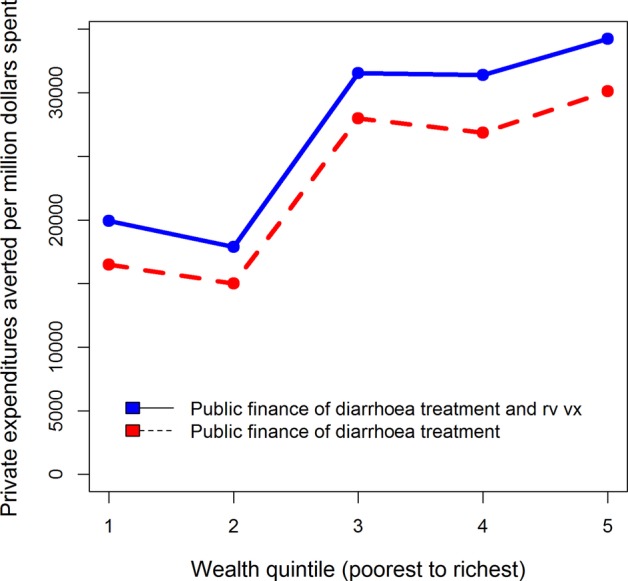

If we view these results per US$1 million spent, diarrhoeal treatment averts approximately 44 deaths and US$115 000 in private expenditures (figures 2 and 3). Rotavirus vaccination and diarrhoeal treatment avert 61 deaths and US$150 000 in private expenditures per US$1 million spent (figures 2 and 3). These summary results provide one outstanding message about these interventions. Rotavirus vaccination with diarrhoeal treatment ‘dominates’ diarrhoeal treatment alone, according to the two measures discussed (lives saved and private expenditures averted).

Figure 2.

Deaths averted, per US$1 000 000 spent, with universal public finance (UPF) of diarrhoeal treatment at a 20-percentage point coverage increase over the current level and rotavirus vaccination at current DTP (diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus) 2 coverage level with diarrhoeal treatment, in Ethiopia.

Figure 3.

Private expenditures averted, per US$1 000 000 spent, with universal public finance (UPF) of diarrhoeal treatment at a 20-percentage point coverage increase over the current level and rotavirus vaccination at current DTP (diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus) 2 coverage level with diarrhoeal treatment, in Ethiopia.

The numbers given above provide important information on the overall impacts of these interventions. However, it is also critical to view results through the equity lens to understand the effects of UPF. Figures 2 and 3 also illustrate how a US$1 million investment in UPF of these interventions is distributed throughout the population. In terms of deaths averted (figure 2), the interventions provide greater benefits to the poor, and the scale of these benefits favours rotavirus vaccination along with diarrhoeal treatment over diarrhoeal treatment alone. Per US$1 million spent across the entire population, about five times as many deaths are averted in the lowest quintile relative to the wealthiest due to UPF of diarrhoeal treatment. The corresponding ratio for UPF of rotavirus vaccination with diarrhoeal treatment is greater than 4. A major reason that both interventions benefit the poorest is the higher burden of diarrhoeal disease among these groups. Examining private expenditures averted demonstrates a different trend (figure 3). For diarrhoeal treatment alone, and diarrhoeal treatment along with rotavirus vaccination, the wealthy tend to experience the greatest gains in private expenditures averted.

Discussion

This paper helps exhibit the potential benefits of providing UPF for two child health interventions in Ethiopia: rotavirus vaccination and diarrhoeal treatment. More specifically, we examine the benefits of UPF of diarrhoeal treatment as well as UPF of both diarrhoeal treatment and rotavirus vaccination. Given the continued focus on equity and UHC, this paper also demonstrates how UPF could provide different benefits across the wealth distribution.

There are three clear messages that result from this work. First, rotavirus vaccination and diarrhoeal treatment together are a better buy than diarrhoeal treatment alone by the two metrics examined in this analysis. Per dollar invested, rotavirus vaccination along with diarrhoeal treatment averts more deaths and more private health expenditures than diarrhoeal treatment alone. Second, the scale of the health benefits is large relative to the financial benefits associated with UPF of these interventions. This does not suggest that OOP expenditures are not large and important for the welfare of the poor. It does, however, indicate that it may be unwise to give equal weight to the health and financial benefits provided by UPF when the scale of the benefits differs. That is, health and financial benefits should be considered by policymakers, and intervention choice should recognise the potential tradeoff between health and financial benefit. Policy choices should then reflect society's preferences for improved health relative to poverty reduction. Third, the health benefits of these interventions are progressive while the financial benefits accrue to wealthier populations. If an objective of UHC or UPF is to improve the equity of the health system, a disproportionate focus on financial risk protection may serve to exacerbate rather than alleviate these inequalities if the relative distribution of benefits is similar for other interventions.

It is interesting to note the equity consequences related to health and financial risk protection for these child health interventions, because diarrhoeal episodes are relatively evenly distributed across wealth quintiles.18 For health conditions where burden or ability to access care is more concentrated among the wealthy, we would likely see a more dramatic distribution of financial benefits in favour of the wealthy. While this analysis does not analyse a case of this type, it does illustrate a potential unintended consequence of UHC. In striving for universality (and including interventions such as tertiary care), policymakers could inadvertently deliver a regressive set of benefits. While this is not the intention of UHC, it does highlight the political economy constraints policymakers face when considering pathways to UHC.

While the bulk of this analysis compares treatment alone, as against treatment along with prevention intervention, there is value in briefly considering the impacts of a vaccination-only policy if only to better understand the outcomes associated with rotavirus vaccination. Per US$1 million spent, rotavirus vaccination averts 685 deaths and US$960 000 in private expenditures. Relative to either treatment alone or treatment paired with rotavirus vaccination, rotavirus vaccination saves more than 10 times as many lives and averts nearly 10 times as many private expenditures per dollar spent. The health impact tends to favour the poor while the financial benefits tend to favour the wealthier. Diarrhoeal treatment is an important life-saving intervention. However, this analysis clearly demonstrates the impressive health and financial outcomes associated with rotavirus vaccination in Ethiopia.

There are several limitations to this analysis. First, this is a static model rather than a dynamic model; hence, herd immunity was not included in the model, though evidence on herd immunity has only been documented in a few countries.21–23 On a related note, this model uses inputs available from the recent past. As newer data becomes available, it would alter the results presented here, but we do not believe that this would dramatically change our results. Second, we have not completed a comprehensive accounting of household medical payments. This analysis does include transport costs but excludes indirect costs associated with time loss and loss of earnings for caregivers. If we were to include additional costs as associated with the loss of earnings, we would expect this to increase the financial risk-protection benefits for both interventions, and make prevention interventions even more attractive per dollar invested. Third, this analysis does not address the needs of households which do not seek care from a health facility or provider.

Conclusion

Using extended cost-effectiveness analysis (ECEA), this paper seeks to inform the debate around publically financed healthcare and UHC by examining the health and financial implications of diarrhoeal treatment as a stand-alone intervention and paired with rotavirus vaccination. We also examine the effects of these interventions by wealth quintile. We find that universal public finance of rotavirus vaccination with diarrhoeal treatment is more ‘cost-effective’ than diarrhoeal treatment on the two metrics we examined. These metrics include deaths averted and private expenditures averted. We also find that most of the health benefits accrue to the poorest wealth quintiles, while the financial benefits favour the wealthy. This result helps illustrate the tradeoffs, both in terms of health versus financial risk protection, as well as across wealth quintiles faced by policymakers when considering reforms towards UHC.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Carol Levin, Robert Black and participants at a Disease Control Priorities 3 authors and editors meeting for valuable comments.

Footnotes

Contributors: DTJ, SV, CP and KAJ conceptualised the study. CP, KAJ, STM and SV contributed to data gathering and analysis. CP and SV wrote the manuscript. All authors have reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Funding: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation funded this work through the Disease Control Priorities Network grant to the University of Washington. CP was an employee of the Gates Foundation at the time this work was undertaken. He was not involved in Gates Foundation funding decisions related to this grant. KAJ and STM were funded through the project Priorities 2020 by a grant from NORAD/the Norwegian Research Council.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. World Health Report 2010—Health Systems Financing, the path to universal coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Universal health coverage . Lancet. Theme issue, published 7 September 2012. http://www.thelancet.com/themed-universal-health-coverage (accessed Feb 2014).

- 3.McIntyre D, Mills A. Research to support universal coverage reforms in Africa: the SHIELD project. Health Policy Plan 2012;27(Suppl 1):i1–3. 10.1093/heapol/czs017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Second global symposium on health systems research. Inclusion and innovation towards universal health coverage. Beijing, 31 October–3 November 2012.

- 5.World Health Organization. World Health Report 2013—Research for Universal Health Coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Margaret Chan. 65th World Health Assembly. 26 May 2012. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2012/wha65_closes_20120526/en/ (accessed Feb 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verguet S, Laxminarayan R, Jamison DT. Universal public finance of tuberculosis treatment in India: an extended cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Econ 2015;24:318–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verguet S, Murphy S, Anderson B et al. . Public finance of rotavirus vaccination in India and Ethiopia: an extended cost-effectiveness analysis. Vaccine 2013;31:4902–10. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70346-8. Verguet S, Olson ZD, Babigumira JB, et al. Health gains and financial risk protection afforded by public financing of selected interventions in Ethiopia: an extended cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet Global Health 2015;3:e288–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70095-1. Verguet S, Gauvreau CL, Mishra S, et al. The consequences of tobacco tax on household health and finances in rich and poor smokers in China: an extended cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet Global Health 2015;3:e206–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker CL, Rudan I, Liu L et al. . Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet 2013;381:1405–16. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60222-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munos MK, Walker CL, Black RE. The effect of oral rehydration solution and recommended home fluids on diarrhea mortality. Int J Epidemiol 2010;39(Suppl 1):i75–87. 10.1093/ije/dyq025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madhi SA, Cunliffe NA, Steele D et al. . Effect of rotavirus vaccine on severe diarrhea in African infants. New Eng J Med 2010;362:289–98. 10.1056/NEJMoa0904797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Bank. World Development Indicators. Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2013. http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators (accessed Feb 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Global health expenditure database. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012. http://www.who.int/nha/country/en/index.html (accessed Feb 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 16.UNICEF. Levels and trends in child mortality. Report 2011. Estimates developed by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation New York: UNICEF, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD 2010 patterns by broad cause group: What diseases and injuries cause the most death and disability globally? http://www.healthmetricsandevaluation.org/gbd/visualizations/gbd-2010-patterns-broad-cause-group

- 18.Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia], ICF International. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, MD: Central Statistical Agency and ICF International, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S et al. . Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet 2012;379: 2151–61. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rheingans RD, Atherly D, Anderson J. Distributional impact of rotavirus vaccination in 25 GAVI countries: estimating disparities in benefits and cost-effectiveness. Vaccine 2012;30S:A15–23. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tate JE, Cortese MM, Payne DC et al. . Uptake, impact, and effectiveness of rotavirus vaccination in the United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011;30:S56–60. 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181fefdc0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yen C, Guardado JAA, Alberto P et al. . Decline in rotavirus hospitalizations and health care visits for childhood diarrhea following rotavirus vaccination in El Salvador. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011;30:S6–10. 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181fefa05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buttery JP, Lambert SB, Grimwood K et al. . Reduction in rotavirus-associated acute gastroenteritis following introduction of rotavirus vaccine into Australia's national childhood vaccine schedule. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011;30:S25–9. 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181fefdee [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stack ML, Ozawa S, Bishai DM et al. . Estimated economic benefits during the ‘decade of vaccines’ include treatment savings, gains in labor productivity. Health Aff 2011;30:1021–8. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization. WHO-CHOICE. http://www.who.int/choice/costs/en (accessed Feb 2014).

- 26.World Bank. Ethiopia: a country status report on health and poverty, Volume 2, Main Report Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamberti LM, Walker CL, Black RE. Systematic review of diarrhea duration and severity in children and adults in low- and middle-income countries. BMC Public Health 2012;12:276 10.1186/1471-2458-12-276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.GAVI alliance. http://www.gavi.org/support/nvs/rotavirus/ (accessed Feb 2014).

- 29.Griffiths UK, Korczak VS, Ayalew D et al. . Incremental system costs of introducing combined DTwP-hepatitis B-Hib vaccine into national immunization services in Ethiopia. Vaccine 2009;27:1426–32. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.12.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]