Abstract

Background

OCD? Not Me! is a novel, web-based, self-guided intervention designed to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in young people aged 12–18, using the principles of exposure and response prevention. The current paper presents the protocol for the development of the programme and for an open trial that will evaluate the effectiveness of this programme for OCD in young people, and associated distress and symptom accommodation in their parents and caregivers.

Methods

We will measure the impact of the OCD? Not Me! programme on OCD symptoms using the Children's Florida Obsessive Compulsive Inventory (C-FOCI), and both the self-report and parent report of the Children's Obsessional Compulsive Inventory—Revised (ChOCI-R). The impact of the programme on OCD-related functional impairment will be measured using the parent report of the Child Obsessive-Compulsive Impact Scale—Revised (COIS-R). Secondary outcome measures include the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale and the Youth Quality of Life—Short Form (YQoL-SF). The 21-item Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21) will be used to measure the impact of the programme on parent/caregiver distress, while the Family Accommodation Scale (FAS) will be used to measure change in family accommodation of OCD symptoms. Multilevel mixed effects linear regression will be used to analyse the impact of the intervention on the outcome measures.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been approved by the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee. The results of the study will be reported in international peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry: ACTRN12613000152729.

Keywords: PSYCHIATRY

Background

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a significant psychological disorder, affecting 0.5–3% of children and adolescents in the community.1–4 It can significantly disrupt academic, social and family functioning, and is associated with deterioration in school performance and poor peer relationships.5 6 OCD often continues into adulthood7 8 and predicts risk of future psychopathology such as social phobia, depression and poor social adjustment.9 As such, early intervention is considered imperative.

Treatment of young people with OCD

Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) in the form of exposure and response prevention (ERP) is the most evidence-supported psychotherapeutic intervention for youth with OCD.10 11 Moreover, the relative safety of ERP and the robustness of treatment response in comparison to psychopharmacological interventions support it as an appropriate first line of treatment for young people with OCD.11 12 This treatment approach utilises a number of therapeutic strategies that aim to teach young people to confront anxiety-provoking stimuli (exposure) without using safety behaviours to reduce anxiety (response prevention).13

Despite the significant amount of evidence supporting the efficacy of ERP for youth with OCD, there are notable limitations regarding the availability, accessibility and administration of this treatment approach.14 For example, ERP is underutilised by mental health professionals,15 16 potentially due to the fact that it can be time consuming and expensive,17 and individuals often suffer from long delays in accessing effective treatment.18 Timely access to effective treatment is critical in OCD as it has been found that rates of symptom remission decrease as the time between symptom onset and treatment increases.19 Given the suboptimal state of effective treatment delivery, it has been suggested that a stepped-care model is a promising treatment approach that maximises clinical benefits from the available resources.17 20 This approach prioritises the availability of treatment options at a range of levels of intensity, and encourages the utilisation of evidence-based treatment at the least intrusive level appropriate to the severity and complexity of a patient's symptoms.21

Current intervention: development protocol

Internet-delivered CBT (iCBT) has been increasingly investigated as a potential solution to the aforementioned issues with treatment accessibility. Evidence now exists for the effectiveness of iCBT for a number of different psychological disorders.22 The majority of existing programmes are therapist-guided, with clients being contacted usually by email or telephone at least once per week. For young people with OCD, therapist-guided iCBT has been shown to be effective.23 However, fully automated, self-guided iCBT programmes for youth with OCD have yet to be evaluated. In keeping with the stepped-care philosophy, it is important to evaluate the effectiveness of completely self-guided interventions as they offer a widely accessible and more resource-efficient treatment option.

Based on the need to advance the stepped-care approach to early-onset OCD treatment,24 we developed OCD? Not Me!—a self-help OCD treatment programme for young people aged 12–18 years that is administered fully online. The programme involves eight stages, and includes established components of ERP, namely: (1) graded, prolonged and real-life exposure to distress-provoking internal or external stimuli; (2) encouragement to reduce, change or eliminate anxiety-reducing rituals; and (3) challenging dysfunctional beliefs via the provision of corrective psychoeducational information.25 The programme is designed to respond to user input, with a number of different interactive elements. For example, ERP exercises are automatically ordered in a hierarchy based on the anxiety rating the participant assigns to them; details of these exercises are carried through the programme and displayed to participants at the appropriate time, participants are able to view their treatment progress on a map as they complete the programme; real-time extinction graphs are displayed as participants input anxiety ratings during an ERP exercise; and graphical feedback of OCD symptoms over time are displayed when participants complete weekly symptom measures. The treatment framework also incorporates the use of metaphors, which has been found to be a clear and engaging way of expressing complex or abstract concepts in CBT for young people.26 The eight stages of the OCD? Not Me! programme correspond to eight treatment modules, designed to be worked through at the rate of one module per week. An overview of the content covered in each stage is provided in table 1.

Table 1.

Stage-by-stage overview of the OCD? Not Me! programme

| Stage | Youth content | Parent content |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction to treatment framework; psychoeducation about OCD and normalisation of symptoms; introduction to self-monitoring; setting goals and planning rewards | Introduction to treatment framework and overview of youth content; psychoeducation about OCD and normalisation of family experiences; understanding habituation; talking to young person about OCD and supporting them through stage 1 |

| 2 | Understanding functional link between obsessions and compulsions; psychoeducation about ERP and rationale for treatment; formulating ERP hierarchy; completing first exposure exercise | Overview of youth content; understanding functional link between obsessions and compulsions; helping young person plan exposure exercises; setting rewards and keeping family motivated |

| 3 | Coping with anxiety; strategies for completing exposure exercises; completing second and third exposure exercises | Overview of youth content; helping young person cope with anxiety; supporting young person through stage 3; psychoeducation around stress within the family and how to manage it |

| 4 | Talking with friends and loved ones about OCD; coping with family stress; psychoeducation around others’ accommodation of OCD symptoms and how to reduce it; coping with self-doubt; completing fourth and fifth exposure exercises | Overview of youth content; helping young person communicate with friends about OCD and address bullying or teasing; psychoeducation around family accommodation of OCD and how to reduce it; coping with own self-doubt and resistance |

| 5 | Receiving planned half-way reward, reflecting on progress in the programme; dealing with setbacks; review of psychoeducational information; completing sixth and seventh exposure exercises | Overview of youth content; motivating young person by celebrating progress; addressing expectations of treatment outcomes; planning for and dealing with setbacks |

| 6 | Psychoeducation around the impact of stress on OCD symptoms; reflecting on goals for treatment and self-appreciation exercise; complete eighth and ninth exposure exercises | Overview of youth content; psychoeducation around the impact of stress on OCD symptoms; strategies for preventing and coping with stress |

| 7 | Review of treatment progress; review of strategies for coping with anxiety; review of motivation for completing treatment; completing final exposure exercise | Overview of youth content; helping young person to consolidate principles of ERP; motivating young person to complete treatment |

| 8 | Receiving planned reward for completing treatment; reflecting on progress in programme; consolidating principles of ERP | Overview of youth content; maintaining treatment progress; celebrating treatment progress; relapse prevention |

ERP, exposure and response prevention; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder.

While the family context of OCD is understudied, extant research suggests that rates of parental OCD, conflict between parents and children, and parental-expressed emotion are higher in families of children who have OCD,27 and that these factors influence treatment outcomes.28 As a result, strategies aimed at addressing family accommodation of a young person's OCD symptoms, reducing parental distress, and improving family communication and problem solving are also considered to be an important aspect of treatment.28 29 In order to assist parents and caregivers to support their young person to complete the OCD? Not Me! programme, a stage-by-stage parent/caregiver resource component was developed for parents and caregivers. In addition to psychoeducational information about OCD and tips on how to help young people to complete each stage of the programme, this component also contains strategies aimed at reducing levels of family distress and accommodation of OCD symptoms. Parents and caregivers are encouraged to read through these resources as their young person completes each stage of the programme, however, they are not required to do so in order for their young person to proceed in the programme. An overview of the content of the parent/caregiver resources that correspond to each stage of the OCD? Not Me! programme is provided in table 1.

In order to ensure that the OCD? Not Me! programme was based on current best practice in OCD treatment for young people, we developed a steering committee consisting of six researchers and practitioners, with known expertise and experience in treating OCD among young people. We asked each member to comment on important aspects of programme development, such as content, length, structure and language, by submitting their feedback via an online questionnaire. The programme protocol was reviewed in line with these recommendations.

A final step in the development of the OCD? Not Me! programme was to adapt the programme protocol for administration online. As online interventions often suffer from low treatment adherence and high attrition rates,30 a number of considerations were taken into account when adapting the programme. In order to maximise treatment and adherence and minimise participant attrition, we aimed to create an accessible and appealing online environment by incorporating elements of persuasive system design found to support behaviour change in internet interventions.30 31 For example, interactive exercises were developed to deliver programme content and personalised feedback, in order to maximise user engagement. The programme was structured so that participants are unable to progress through the programme without completing the previous stage. An automated system of reminder emails (reminding participants to log into the programme after a week of inactivity) was also developed, with the aim of improving programme adherence. Finally, in order to optimise treatment access for users who require more specialised or intensive face-to-face services, we developed a national referral database, which was incorporated into the programme website (http://www.ocdnotme.com.au). This database allows users to search for mental health providers in their local area, and also provides youth mental health crisis and support hotline details.

Following development of the programme content and website, we implemented a two-stage testing and audit process with two primary aims (1) to evaluate the usability of the website using a participant drawn from our target demographic; and (2) to maximise the security of data collected online. In order to address the first aim, we recruited a young person and parent/caregiver dyad from our target demographic who presented at the Curtin Psychology Clinic seeking treatment for OCD. After providing informed consent to participate in the preliminary trial of the OCD? Not Me! programme, this dyad was invited to work through the programme using a computer located at the Curtin Psychology Clinic. This trial consisted of four sessions over 4 weeks, and was conducted with the assistance of a therapist familiar with the programme, who was available to answer questions regarding programme content or technical issues. Feedback was obtained from both the young person and their parent/caregiver regarding the ease of use of the programme, the relevance of programme content, and the time taken to complete various aspects of the assessment and intervention process. Further revisions to the programme were made in line with the feedback received.

To address the second aim, an independent security and vulnerability audit was undertaken to identify potential security risks associated with the data collection processes enacted in the OCD? Not Me! programme. Areas of risk were addressed in line with recommendations provided by the auditors, and an ongoing vulnerability management plan was developed.

Current intervention: research protocol

Once the programme had been developed and reviewed, and online data security risks had been addressed, a SPIRIT-compliant research protocol (see table 2) was developed to evaluate the effectiveness of the programme for reducing OCD symptoms and related distress in the target population.

Table 2.

Items from the WHO trial registration

| Sources of monetary or material support | Australian Government Department of Health Curtin University |

| Primary sponsor | Australian Government Department of Health |

| Contact for public queries | ocdnotme@curtin.edu.au |

| Contact for scientific queries | ocdnotme@curtin.edu.au |

| Public title | OCD? Not Me! Curtin online OCD treatment for young people |

| Scientific title | An open trial of a fully automated computer self-help cognitive-behavioural intervention for youth with OCD |

| Country of recruitment | Australia |

| Health condition(s) or problem(s) studied | Obsessive-compulsive disorder |

| Intervention(s) | OCD? Not Me! is a self-guided, web-based intervention that involves eight stages |

| Key inclusion and exclusion criteria | Inclusion: 12–18 years of age; Australian resident; current symptoms of OCD (SOCS ≥2) Exclusion: current symptoms of eating disorder (SCOFF questionnaire ≥2); current symptoms of psychosis (APSS ≥4); current self-harm or suicide risk (moderate-high) |

| Study type | Interventional |

| Date of first enrolment | 7 October 2013 |

| Target sample size | 150 |

| Recruitment status | Recruiting |

| Primary outcome(s) | Change in: OCD symptoms (C-FOCI; ChOCI-R self-report; ChOCI-R parent report), OCD-related functional impairment (COIS-R parent report) |

| Key secondary outcomes | Change in: Quality of life (YQoL-SF), self-esteem (RSES), parental distress (DASS-21), family accommodation of OCD symptoms (FAS-SR) |

APSS, Adolescent Psychotic-Like Symptom Screener; C-FOCI, Children's Florida Obsessive Compulsive Inventory; ChOCI-R, Children's Obsessional Compulsive Inventory—Revised; COIS-R, Child Obsessive-Compulsive Impact Scale—Revised; DASS-21, 21-item Depression Anxiety Stress Scales; FAS-SR, Family Accommodation Scale for Obsessive Compulsive Disorder—Self-Rated Version; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; RSES, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; SOCS, Short OCD Screener; YQoL-SF, Youth Quality of Life—Short Form.

Aims and hypotheses

The main aim of the OCD? Not Me! research trial is to investigate whether the OCD? Not Me! treatment programme is effective in reducing obsessive-compulsive symptoms among young Australians aged 12–18 years with a primary diagnosis of OCD. Secondary aims were to investigate the effectiveness of the programme for improving psychological well-being (measured in terms of quality of life and self-esteem) among young people with OCD, and for reducing psychological distress and family accommodation of OCD symptoms among their parents and caregivers.

Our primary hypothesis is that young people will show a significant reduction in OCD symptoms at post-treatment compared with pretreatment. A secondary hypothesis is that young people will show a significant improvement in self-esteem and quality of life at post-treatment compared with pretreatment. In addition, we hypothesise that parents and caregivers will report reductions in their levels of psychological distress, and of family accommodation of OCD symptoms, post-treatment compared with pretreatment.

Methods/design

Study design and data analysis

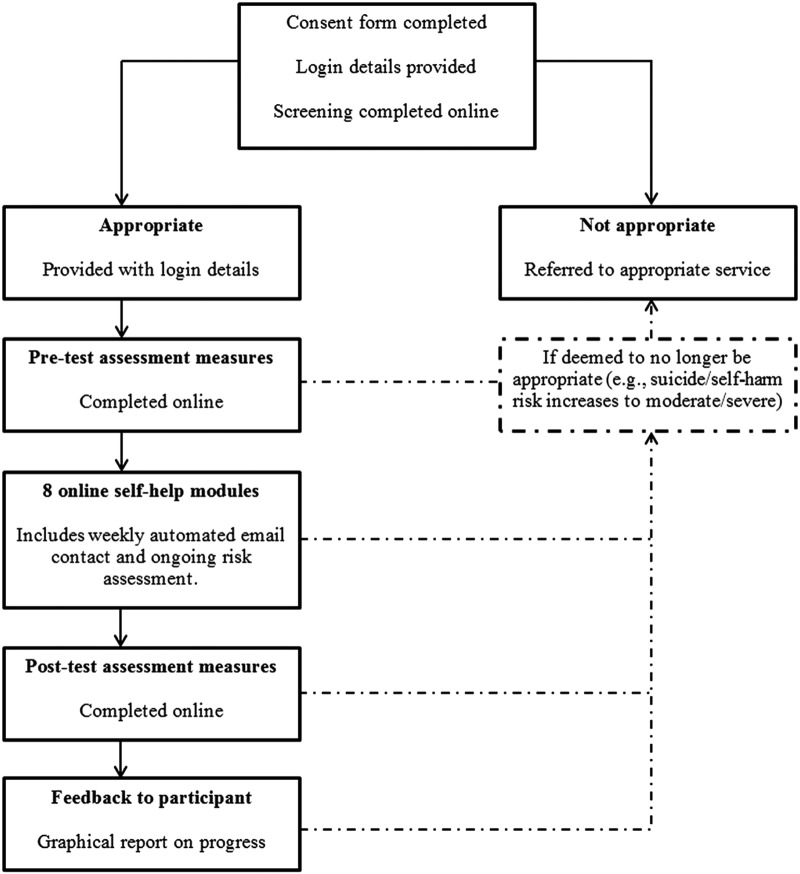

We will conduct an open trial, using a pretest post-test within-groups design to evaluate change on outcome measures. This research design is recommended when conducting preliminary research on the effectiveness and feasibility of novel treatments.32 Following screening, eligible participants will complete the outcome measures at time 1 and then again following completion of the programme at time 2 (post-test). The flow of participants through the study is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through study.

Sample size

Sample size calculations were based on a moderate effect size at the conventional α level of 0.05. A moderate effect size was estimated on the basis of results from a review of self-help treatments for anxiety disorders in young people.33 Based on this, it was calculated that a minimum of 45 participants is required to adequately power the study. The literature on which to base estimated attrition rates was limited, however, a randomised controlled study of internet-based CBT for child anxiety disorders indicated a screening exclusion/dropout rate of 38% and a further 25% dropout rate from the treatment condition.34 It should be noted that in this study, screening and pretesting assessments were conducted with trained interviewers via telephone. Based on this estimate, and taking into account the fully automated nature of the screening and pretesting process in the current trial, we aimed to recruit 150 participants to the screening process to account for participants lost to screening, pretesting and later attrition during treatment.

Participants

We aim to evaluate the effectiveness of the programme in a sample of young people (aged 12–18) residing in Australia. Eligible participants are Australian residents aged 12–18 years who are currently exhibiting symptoms of OCD, as determined by their score on the Short OCD Screener (SOCS),35 who speak English and who have internet access and an email address. In addition, participants are not eligible if they report current moderate-high self-harm or suicide risk as measured by the suicide risk module of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID).36 This module contains 14 yes/no questions that produce a dichotomous suicide risk rating (present or not present) as well as a numeric suicide risk score with identified anchors for ‘low’, ‘moderate’ and ‘high’ suicide risk. This module has shown good to excellent inter-rater and retest reliabilities for current and lifetime suicidality (area under the curve=0.89–0.99, κ=0.81–0.96).36 Further exclusion criteria include elevated symptoms of eating disorder or psychosis, as measured by the SCOFF questionnaire37 and the Adolescent Psychotic-Like Symptom Screener (APSS).38

Recruitment

Recruitment of participants to the OCD? Not Me! programme is via existing referral networks of general practitioners mental health professionals, as well as through advertising in print media and on social networking sites. As part of the referral process, information about the programme is provided via conference/workshop presentations and direct communication with specialist healthcare providers.

Procedure

Young people and their parents and caregivers are invited to register for the study by accessing the website (http://www.ocdnotme.com.au), and are able to provide informed consent to participate in the programme by following an online consent procedure. Once informed consent has been provided, participants receive secure login details that enable them to log into the screening assessments and, if eligible, to access the programme. To determine whether the OCD? Not Me! programme is appropriate for the young person's current symptoms, they are invited to complete the screening measures described above. These measures are administered online via the website and are automatically scored to immediately determine programme suitability. If the programme is deemed suitable, the young person is then invited to complete the young person pre-programme assessment battery described below. In addition, parents and caregivers receive an email notification informing them that the OCD? Not Me! programme has been deemed suitable for their young person's current needs. Parents and caregivers are also required to complete the parent/caregiver pre-programme assessment battery described below, by clicking on a link provided in the email. As with the screening measures, the pre-programme assessments are administered and scored entirely online, via the website. Once eligible participants and their parents/caregivers have completed the pre-programme assessment batteries, young people then receive cumulative access to the eight-stage online programme. As participants begin each stage, an automated email is sent to parents/caregivers with a link to the supporting resources for that stage. As the programme is fully automated, no clinician contact is utilised throughout the assessment or treatment process, or in the follow-up of idle accounts. Participants who do not log into their account for a week receive an automated email reminding them to login. Should the participant's account remain idle, this email is resent once a week for 3 weeks. At the end of this period, participants who have not logged into the programme in the preceding month are locked out of their account. They are able to access the programme if they complete the registration and pretesting period again. A participant is considered a dropout if their account is idle for 1 month.

If the programme is not deemed suitable for the young person, they are immediately notified, and their parent/caregiver will receive an email informing them of the outcome of the screening assessment. In addition, if young people indicate during the screening assessment that they are currently experiencing moderate-high risk of self-harm or suicide, their parents/caregivers will receive a separate email informing them of this risk, with information and resources on how to manage it. Parents and caregivers are invited to seek out more intensive and specialised services using the national referral database.

Diagnostic assessment

In order to establish a diagnosis of OCD and to determine the presence of other comorbid diagnoses, we developed the Youth Online Diagnostic Assessment (YODA). The YODA is an online self-report measure designed to assess psychiatric symptoms in young people according to the diagnostic criteria outlined in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V).39 Development of the YODA for the purpose of this study was necessary because there were no comprehensive psychiatric assessments available for young people that were (A) self-report format; (B) designed for online administration and (C) available free or at minimal cost. The YODA covers the following disorders: OCD, separation anxiety disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, panic disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, major depressive episode, dysthymia, post-traumatic stress disorder, bulimia, anorexia, tic disorders, Tourette's disorder, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder and pervasive developmental disorder.

Outcome measures—young people

To capture detailed data on young people's OCD symptoms and their well-being before and after the programme, we constructed a comprehensive assessment battery from a number of extant measures. These measures are described in detail below.

The Children's Florida Obsessive Compulsive Inventory

The Children's Florida Obsessive Compulsive Inventory (C-FOCI)40 was selected to assess OCD symptoms. This measure is a brief self-report measure of OCD symptoms in children and adolescents, comprising a 17-item symptom checklist and a 5-item severity scale. The C-FOCI was selected because it has been validated for internet administration and is suitable to compare with the Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS).35 While the clinician-administered version of the CY-BOCS is often cited as the gold standard measure of OCD symptoms in young people, the self-report version performs less well—as a result, it has been argued that this measure is not feasible for use outside clinical settings.40 The C-FOCI has demonstrated adequate internal consistency, and convergent and discriminant validity.40 In addition to pretest and post-test administration, participants are asked to complete the C-FOCI prior to starting each stage of the programme.

Children's Obsessive Compulsive Inventory—Revised

The self-reported Children's Obsessive Compulsive Inventory—Revised (ChOCI-R)41 was selected as a secondary measure of OCD symptoms. This 32-item measure comprises 20 questions that evaluate the presence of specific obsessions and compulsions in children and adolescents, and 12 questions that assess severity of OCD symptoms and associated impairment. The ChOCI-R has demonstrated excellent internal consistency, and good convergent and discriminant validity.41

The Youth Quality of Life Instrument—Short Form

The Youth Quality of Life Instrument—Short Form (YQoL-SF)42 was chosen to measure quality of life. The YQoL-SF is a 16-item self-report scale that provides a multidimensional assessment of quality of life among children and adolescents. Psychometric data for the longer version of the scale (the Youth Quality of Life Instrument—Revised) support the reliability and validity of this instrument.42

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES)43 was chosen to measure self-esteem. This 10-item measure was designed to assess self-esteem among children and adolescents, and is the most widely used measure of self-esteem available. The RSES has adequate internal reliability and evidence supports the construct validity of this measure.43–45

Feedback questionnaire

A 10-item online feedback questionnaire was developed to assess participants’ experience of the OCD? Not Me! programme. This self-report questionnaire uses a combination of Likert-type response scales and open-ended questions to assess various dimensions of participant experience including enjoyment, relevance, satisfaction and degree of completion. This survey is automatically issued via email link when participants exit the programme (subsequent to withdrawal, dropout or completion).

Outcome measures—parents and caregivers

The aim of including outcome measures for parents and caregivers was threefold: (A) to collect parent/caregiver reports of their young person's OCD symptoms; (B) to assess parent/caregiver involvement in their young person's OCD rituals and (C) to assess parent/caregiver distress. The measures included in the parent/caregiver assessment battery are described below.

ChOCI-R (parent report)

The parent-report version of the ChOCI-R was selected to corroborate the self-report version of the ChOCI-R administered to the young person. Similar to the self-report version of this scale, the parent report comprises 20 questions that evaluate the presence of specific obsessions and compulsions in children and adolescents, and 12 questions that assess severity of OCD symptoms and associated impairment. Psychometric evaluation of this scale has indicated that it displays good internal consistency, and convergent and divergent validity, and that item and scale scores share strong correlations with scores on the self-report scale.41

Child Obsessional Impact Scale—Revised

The parent-report version of the Child Obsessional-Compulsive Impact Scale—Revised (COIS-R)46 was selected to assess the degree to which OCD symptoms were causing functional impairment in the young person. This 33-item measure assesses OCD-specific functional impairment across four domains (daily living skills, school, social, family/activities) and has good internal consistency, concurrent validity and test-retest reliability.46

Family Accommodation Scale for Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

The Family Accommodation Scale for Obsessive Compulsive Disorder—Self-Rated Version (FAS-SR)47 was chosen to measure the degree to which family members facilitate or participate in a young person's OCD-related rituals and/or avoidance. This 19-item measure has demonstrated excellent internal consistency and strong convergence with criterion measures.47

21-Item Depression Anxiety Stress Scales

The 21-item version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21)48 was selected to measure parental distress. This scale is designed to measure psychophysiological symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress, in clinical and non-clinical populations. Psychometric evaluation of this scale has indicated that it demonstrates adequate internal consistency and concurrent validity.

Data analyses

Multilevel mixed effects linear regression will be used to evaluate change on the outcome measures. A generalised linear mixed model (GLMM) procedure will be used to test for the effect of time in the context of a hierarchical design, with time treated as a fixed effect, and participants treated as a random effect. The primary benefit associated with using the GLMM maximum likelihood procedure is that it maximises statistical power and reduces the impact of sampling bias due to participant attrition, as it does not rely on all participants providing data at each time point.49 In addition, GLMM can account for unequally spaced data collection points and correlations between repeated measurements.50 Because this procedure uses all available data at each time point, it is particularly useful for conducting intent-to-treat analyses.50

Significant main effects for time will be followed up with pairwise contrasts to compare pretreatment to post-treatment scores on each of the outcomes measures. Effect sizes will be calculated within groups, using the formula provided by Cohen.51 In addition, we will calculate the proportion of participants who report reliable and clinically significant change on the C-FOCI and ChOCI, using the methodology proposed by Jacobson and Truax.52

Data collection and monitoring

Data will be collected and managed in line with the Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research.53 As part of the intervention development, software was developed to automatically and securely monitor, score and download data collected online. Members of the research team are responsible for overseeing and monitoring data collection, and for providing progress reports to the Australian Government Department of Health.

To motivate participants to engage with the programme and to promote participant retention, participants are offered one entry into a prize draw for a gift card valued at $A30 when they reach the halfway point of the programme. Identifying data collected from participants for the purpose of notifying them about the results of the prize draw is automatically separated from other data collected.

Ethics

The Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee approved the study protocol, and the trial was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12613000152729).

Methodological considerations

The current study has several strengths, including the repeated measurement of OCD symptoms, and suicide and self-harm risk at the beginning of each stage of the OCD? Not Me! programme. The use of repeated measurements allows us to monitor and respond to risk, as well as to analyse trajectories of change in OCD symptoms over the course of the programme. In addition, the inclusion of a broad range of outcome measures, such as self-esteem, family accommodation and family distress, allows us to evaluate the impact of the programme on clinically meaningful outcomes relating to quality of life and family functioning. Some limitations must also be acknowledged. First, the validity of the study may be affected by the use of a diagnostic measure (YODA) that has not yet been validated, and the reliance on self-report measures.

Second, the absence of a control condition due to the open trial design limits conclusions about the efficacy of the programme.

Discussion

This paper presents the protocol of a study designed to assess the effectiveness of a novel, online, self-guided programme for the treatment of young people with OCD. While CBT with ERP is currently considered the first-line treatment for youth with OCD,10 considerable issues in the dissemination and take up of this treatment in its face-to-face format have given rise to a call for a stepped-care approach.54 Internet-based self-help interventions are an important contribution to the stepped-care approach, and there is growing evidence to support the effectiveness of such interventions in treating a range of mental health problems.55 56 Despite this, there are few studies that have evaluated the effectiveness of such programmes for treating youth with OCD.

Conclusion

We believe that this is the first study to evaluate a fully automated, self-guided iCBT intervention for OCD among youth. The intervention described in the current study is an innovative, fully online programme that utilises the principles of ERP to address the symptoms of OCD in young people. In addition, the programme provides psychoeducational resources and support for family members, with the aim of reducing levels of family accommodation of OCD symptoms, and alleviating psychological distress among parents and caregivers. This intervention represents a viable low-intensity treatment for young people with OCD.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Amy Finlay-Jones at @amyfinlayjones

Contributors: CSR helped conceive of the study, developed the intervention, participated in the design of the study and helped draft the manuscript. RAA helped conceive of the study, developed the intervention and participated in the design of the study. AF-J helped develop the intervention, participated in the design of the study and drafted the manuscript.

Funding: This work was support by the Australian Government Department of Health, grant number DoHA/279/1112.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: As the study is still recruiting participants, data are currently being collected, and is at present only available to the researchers. The data are downloaded directly from the online programme described in this article, using software that de-identifies the data from any personal information associated with it.

References

- 1.Moore PS, Mariaskin A, March J et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents: diagnosis, comorbidity, and developmental factors. In: Storch EA, Geffken GR, Murphy TK, eds. Handbook of child and adolescent obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc., 2007:17–45. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rapoport J, Inoff-Germain G, Weismann MM et al. Childhood Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in the NIMH MECA study: parent versus child identification of cases. J Anxiety Disord 2000;14:535–48. 10.1016/S0887-6185(00)00048-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heyman I, Fombonne E, Simmons H et al. Prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the British nationwide survey of child mental health. Int Rev Psychiatry 2003;15:178–84. 10.1080/0954026021000046146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walitza S, Melfsen S, Jans T et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents. Deutsches Arzteblatt 2011;108:173–9. 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piacentini J, Bergman RL, Keller MB et al. Functional impairment in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2003;13(Suppl 1):61–9. 10.1089/104454603322126359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valderhaug R, Ivarsson T. Functional impairment in clinical samples of Norwegian and Swedish children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur J Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005;14:164–73. 10.1007/s00787-005-0456-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leonard HL, Swedo SE, Lenane MC et al. A 2- to 7-year follow-up study of 54 obsessive-compulsive children and adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993;50:429–39. 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820180023003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stewart SE, Geller DA, Jenike M et al. Long-term outcome of pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis and qualitative review of the literature. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2004;110:4–13. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00302.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wewetzer C, Jans T, Müller B et al. Long-term outcome and prognosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder with onset in childhood or adolescence. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;10:37–46. 10.1007/s007870170045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrett PM, Farrell L, Pina AA et al. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent obsessive compulsive disorder. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2008;37:131–55. 10.1080/15374410701817956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman J, Garcia A, Frank H et al. Evidence base update for psychosocial treatments for pediatric obsessive compulsive disorder. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2014;43:7–26. 10.1080/15374416.2013.804386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watson H, Rees CS. Meta-analysis of randomized, controlled treatment trials for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2008;49:489–98. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01875.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Himle MB, Franklin ME. The more you do it, the easier it gets: exposure and response prevention for OCD. Cogn Behav Pract 2009;16:29–39. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2008.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodwin R, Koenen KC, Hellman F et al. Helpseeking and access to mental health treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2002;106:143–9. 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.01221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valderhaug R, Gotestam KG, Larsson B. Clinicians’ views on management of obsessive-compulsive disorders in children and adolescents. Nord J Psychiatry 2004;58:125–32. 10.1080/08039480410005503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krebs G, Isomura K, Lang K et al. How resistant is ‘treatment-resistant’ obsessive-compulsive disorder in youth? Br J Clin Psychol 2015;54:63–75. 10.1111/bjc.12061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maltby N, Tolin DF. Overview of treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorder and spectrum conditions: conceptualization, theory, and practice. Brief Treat Crisis Interv 2003:127–44. 10.1093/brief-treatment/mhg011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krebs G, Heyman I. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents. Arch Dis Child 2014;100:1–5. 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mancebo MC, Boisseau CL, Garnaat SL et al. Long-term course of pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: three years of prospective follow-up. Compr Psychiatry 2014;55:1498–504. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bower P, Gilbody S. Stepped care in psychological therapies: access, effectiveness and efficiency. Br J Psychiatry 2005;186:11–17. 10.1192/bjp.186.1.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Obsessive-compulsive disorder: core interventions in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersson G, Cuijpers P, Calbring P et al. Guided internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 2014;13:288–95. 10.1002/wps.20151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lenhard F, Vigerland S, Andersson E et al. Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: An open trial. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e100773 10.1371/journal.pone.0100773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wootton BM, Titov N. Distance treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Change 2010;27:112–18. 10.1375/bech.27.2.112 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franklin ME, Foa EB. Treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2011;7:229–43. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ronen T. Using metaphors in therapy. The positive power of imagery: harnessing client imagination in CBT and related therapies. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2011:123–35. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waters T, Barrett P. The role of the family in childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2000;3:173–84. 10.1023/A:1009551325629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piacentini J, Langley A. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for children who have obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychol 2004;60:1181–94. 10.1002/jclp.20082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barrett PM, Healy-Farrell L, March JS. Cognitive-behavioral family treatment of childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder: a controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004;43:46–62. 10.1097/00004583-200401000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelders SM, Kok RN, Van Gemert-Pijnen JEWC. Persuasive system design does matter: a systematic review of adherence to web-based interventions. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:e152 10.2196/jmir.2104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ritterband LM, Thorndike FP, Cox DJ et al. A behavior change model for internet interventions. Ann Behav Med 2009;38:18–27. 10.1007/s12160-009-9133-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chambless DL, Hollon SD. Defining empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998;66:7–18. 10.1037/0022-006X.66.1.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rickwood D, Bradford S. The role of self-help in the treatment of mild anxiety disorders in young people: an evidence-based review. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2012;5:25–36. 10.2147/PRBM.S23357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.March S, Spence SH, Donovan CL. The efficacy of an internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention for child anxiety disorders. J Pediatr Psychol 2009;34:474–87. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uher R, Heyman I, Mortimore C et al. Screening young people for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry 2007;191:353–4. 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.034967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheehan D, Sheehan K, Shytle D et al. Reliability and validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for children and adolescents. J Clin Psychiatry 2009;71:313–26. 10.4088/JCP.09m05305whi [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacey JH. The SCOFF questionnaire: assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ 1999;319:1467–8. 10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelleher I, Harley M, Murtagh A et al. Are screening instruments valid for psychotic-like experiences? A validation study of screening questions for psychotic-like experiences using in-depth clinical interview. Schizophr Bull 2011;37:362–9. 10.1093/schbul/sbp057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Storch EA, Khanna MS, Merlo LJ et al. Children's Florida Obsessive Compulsive Inventory: psychometric properties and feasibility of a self-report measure of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in youth. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2009;40:467–83. 10.1007/s10578-009-0138-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uher R, Heyman I, Turner CM et al. Self-, parent-report and interview measures of obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents. J Anxiety Disord 2008;22:979–90. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patrick DL, Edwards TC, Topolski TD. Adolescent quality of life, part 11: initial validation of a new instrument. J Adolesc 2002;25:287–300. 10.1006/jado.2002.0471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whiteside-Mansell L, Corwyn RF. Mean and covariance structure analyses: an examination of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale among adolescents and adults. Educ Psychol Meas 2003;63:163–73. 10.1177/0013164402239323 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bagley C, Mallick K. Normative data and mental health construct validity for the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in British adolescents. Int J Adolesc Youth 2001;9:117–26. 10.1080/02673843.2001.9747871 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piacentini J, Peris TS, Bergman RL et al. BRIEF REPORT: functional impairment in childhood OCD: development and psychometric properties of the Child Obsessive-Compulsive Impact Scale-Revised (COIS-R). J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2007;36:645–53. 10.1080/15374410701662790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pinto A, Van Noppen B, Calvocoressi L. Development and preliminary psychometric evaluation of a self-rated version of the Family Accommodation Scale for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord 2013;2:457–65. 10.1016/j.jocrd.2012.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lovibond S, Lovibond P. Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales. Sydney: Psychology Foundation, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garson GD. Fundamentals of hierarchical linear (multilevel) modeling. In: Garson GD. ed. Hierarchical linear modeling: guide and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2013:3–25. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kwok O-M, Underhill AT, Berry JW et al. Analyzing longitudinal data with multilevel models: an example with individuals living with lower extremity intra-articular fractures. Rehabil Psychol 2008;53:370–86. 10.1037/a0012765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992;112:155–9. 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991;59:12–19. 10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.National Health and Medical Research Counsel. Australian code for the responsible conduct of research. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government 2007:s2.1–2.2. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rees C, Anderson RA. New approaches to the psychological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder in adults. In: Durbano F. ed. New insights into anxiety disorders. InTech, 2013. http://www.intechopen.com/books/new-insights-into-anxiety-disorders/new-approaches-to-the-psychological-treatment-of-obsessive-compulsive-disorder-in-adults [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mataix-Cols D, Marks D. Self-help with minimal therapist contact for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a review. Eur Psychiatry 2006;21:75–80. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tumur U, Kaltenthaler E, Ferriter M et al. Computerised cognitive behaviour therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review. Psychother Psychosom 2007;76:196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]