Abstract

Background

Medical complications after severe traumatic brain injury (S-TBI) may delay or prevent transfer to rehabilitation units and impact on long-term outcome.

Objective

Mapping of medical complications in the subacute period after S-TBI and the impact of these complications on 1-year outcome to inform healthcare planning and discussion of prognosis with relatives.

Setting

Prospective multicentre observational study. Recruitment from 6 neurosurgical centres in Sweden and Iceland.

Participants and assessments

Patients aged 18–65 years with S-TBI and acute Glasgow Coma Scale 3–8, who were admitted to neurointensive care. Assessment of medical complications 3 weeks and 3 months after injury. Follow-up to 1 year. 114 patients recruited with follow-up at 1 year as follows: 100 assessed, 7 dead and 7 dropped out.

Outcome measure

Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended.

Results

68 patients had ≥1 complication 3 weeks after injury. 3 weeks after injury, factors associated with unfavourable outcome at 1 year were: tracheostomy, assisted ventilation, on-going infection, epilepsy and nutrition via nasogastric tube or percutaneous endoscopic gastroscopy (PEG) tube (univariate logistic regression analyses). Multivariate analysis demonstrated that tracheostomy and epilepsy retained significance even after incorporating acute injury severity into the model. 3 months after injury, factors associated with unfavourable outcome were tracheostomy and heterotopic ossification (Fisher's test), infection, hydrocephalus, autonomic instability, PEG feeding and weight loss (univariate logistic regression). PEG feeding and weight loss at 3 months were retained in a multivariate model.

Conclusions

Subacute complications occurred in two-thirds of patients. Presence of a tracheostomy or epilepsy at 3 weeks, and of PEG feeding and weight loss at 3 months, had robust associations with unfavourable outcome that were incompletely explained by acute injury severity.

Keywords: REHABILITATION MEDICINE, TRAUMA MANAGEMENT

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a study of a relatively large cohort with prospective recruitment early after injury unrelated to any later decision on rehabilitation admission, and a high rate of follow-up despite logistical difficulties in this severely injured population.

This study spans all phases of the chain of care after severe traumatic brain injury, from acute to rehabilitation care to long-term follow-up. This is important as data on medical complications spanning acute and rehabilitation care is needed to support development of services to manage medical and rehabilitation needs at all stages of recovery: recent data have shown outcome benefits with early rehabilitation interventions, which may be impossible if rehabilitation units cannot safely care for patients with on-going medical complications.

This study contributes data to support clinical assessment of prognosis, which in the real world is an iterative process whereby the clinician synthesises data on all preceding acute and subacute events in discussions with patients and relatives.

The exclusion of children and older adults due to logistical reasons is a limitation. These groups are prone to traumatic brain injury and should be included in future studies.

Data on occurrence of paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity were limited by the study design and the lack of consensus criteria for diagnosis during the study period.

Introduction

Severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), often defined by acute Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) 3–8, may require a lengthy hospital stay and is an important cause of long-term disability.1 After prehospital care and neurointensive care, most patients require inpatient rehabilitation before discharge to the community. Total length of hospital stay can vary from weeks to several months.2 Some patients with severe TBI recover relatively well and in the long term return to work,3 while for others support at home or continuing institutional care may be necessary.

An understanding of medical complications and needs during the entire pathway of care from injury to rehabilitation discharge is important for care of the individual patient, for healthcare planning and in order to target features where intervention could improve outcome. During initial neurointensive care, close monitoring and management of impaired vital functions are integral components of care and equipment, staffing levels and training are appropriate to the patient's extensive medical needs. Minimising secondary brain injury4 is a central management theme, encompassing optimisation of intracranial pressure, seizure management and avoidance of hypoxia or hypoperfusion. In parallel, efforts are made to prevent, diagnose and manage complications of immobilisation (eg, infections, venous thromboembolism (VTE)).

Subacute complications and initiation of brain injury rehabilitation

Timely transfer to rehabilitation is supported by recent reports demonstrating outcome benefits5 and cost-effectivity6 of a continuous chain of care from the intensive care unit to inpatient rehabilitation to discharge. However, within many current care structures, on-going medical complications and/or a need for medical monitoring are considered to be factors preventing transfer to rehabilitation. Data now emerging7 show that subacute medical complications are common after severe TBI, and as such that this linear concept of medical stability before transfer to rehabilitation is an oversimplification that does not match with patients’ needs. The British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine recently proposed standards for trauma care including definitions of time points for transfer to rehabilitation,8 but international standards are lacking.

Many of the complications that may occur during neurointensive care (eg, paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity (PSH)9) may persist after discharge, and some (eg, hydrocephalus,10 heterotopic ossification11) may have their onset during this later stage of recovery. Clinicians caring for patients in the subacute phase after injury need to have brain injury expertise in order to ensure timely diagnosis and optimal management of complications. A recent study7 of patients with disorders of consciousness after severe TBI found a high rate of medical complications over an extended period of many weeks after injury. However, that and other7 10 12 recent studies of postacute complications are limited in their generalisability by a focus on selected patients admitted to specialised rehabilitation. An improved evidence base on rates and nature of complications in the subacute period after injury is needed for development of international standards.

Subacute complications and associations with outcome

Outcome prediction after severe TBI is important for patients, relatives, clinicians and healthcare planners, as a foundation for planning of appropriate medical, rehabilitation and social interventions. Previous studies of factors predictive of outcome have focused on recording various markers of acute injury severity with evaluation of outcome months later.13 14 Such studies have value but essentially ignore subacute complications and any rehabilitation interventions between injury and follow-up, and only explain about 35% of the variability in outcome.15

In a previous study,2 we found that, having controlled for acute prognostic variables known to impact on outcome, length of stay in intensive care, time between intensive care and rehabilitation admission, and the presence of any medical complication 3 weeks after injury were all associated with unfavourable outcome 1 year after injury. In this study, we explore further rates of specific complications and associations of these with outcome at 1 year. Medical complications in the subacute phase of recovery could impact on outcome directly (eg, through secondary brain injury) and indirectly (eg, through delayed transfer to rehabilitation), and have the potential to contribute to more nuanced prognostic predictions in the subacute phase after injury.

Methods

This study formed part of a prospective, multicentre, observational study of patients who had sustained severe TBI (the ‘PROBRAIN’ study2).

Inclusion criteria were

Severe, non-penetrating, TBI, with a lowest non-sedated GCS 3–8 or equivalent scores on the Swedish Reaction Level Scale16 in the first 24 h after injury.

Age at injury 18–65 years.

Injury requiring neurosurgical intensive care, or collaborative care with a neurosurgeon in another intensive care unit.

Exclusion criteria were death or expected death within 3 weeks of injury.

Patients were recruited prospectively by rehabilitation physicians from January 2010 until June 2011, with extended recruitment until December 2011 at two centres. Neurosurgical intensive care units at six (out of a possible 7) centres in Sweden and Iceland were contacted on a weekly basis to identify eligible patients. The participating centres provide neurosurgical care to the majority of the population of Sweden, and the population of Iceland. The patient gave informed consent in cases where he/she had the capacity to. In the majority of cases the patient lacked capacity and the patient's nearest relative gave consent to inclusion.

After inclusion, acute and socioeconomic data were obtained from medical records. Patients then underwent prospective clinical assessment at three time points:

Three weeks (18–24 days),

Three months (75–105 days),

One year (350–420 days) after injury.

Assessments took place in the patient's current care setting or in a local outpatient department. Inclusion and follow-up were therefore independent of the patient's clinical course and care setting. Assessments were performed by rehabilitation physicians with assistance from rehabilitation nurses, psychologists, physiotherapists and occupational therapists.

Medical complications were assessed at each time point. Choice of variables was based on medical complications reported in the literature and/or encountered in clinical acute rehabilitation practice and is summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of medical features assessed 3 weeks and 3 months after injury

| Area | Features assessed/recorded |

|---|---|

| Respiration | Tracheostomy tube Ventilator support Oxygen therapy |

| Infection status | Current infection |

| Venous thromboembolism | Pulmonary embolus Deep vein thrombosis |

| Cerebrospinal fluid circulation | Hydrocephalus |

| Autonomic instability | Tachycardia*≥100 Systolic blood pressure* ≥150 Primary temperature dysregulation* |

| Epilepsy | Seizures |

| Heterotopic ossification | Presence of heterotopic ossification (clinical assessment) |

| Nutrition | Weight, length Nasogastric or gastrostomy (PEG) feeding |

*In the absence of on-going infection.

PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy.

Certain features were considered to be markers of impaired function (eg, the presence of a tracheostomy tube) and as such were included in the broad definition of medical complications. Specifically, the following were assessed: presence of a tracheostomy tube, on-going ventilator treatment, oxygen therapy, pulmonary embolus or deep vein thrombosis; and the presence of hydrocephalus and any treatment for this, current infections, nutrition via nasogastric (NG) tube or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube, epilepsy, heterotopic ossification. Primary temperature dysregulation in the absence of on-going infection and/or raised pulse or blood pressure at the time of assessment (pulse ≥100, systolic blood pressure ≥150), were considered indicators of possible autonomic instability or PSH.12 Length and weight were recorded at each time point. Epilepsy was recorded as present if the patient had experienced seizures requiring treatment with antiepileptic medication in the period prior to the current assessment. The diagnoses of absence of heterotopic ossification was a clinical judgment, based on clinical assessment and review of the notes.

Other features that may occur after brain injury were not included in this analysis for the following reasons: evaluation of association of continence with outcome was not possible as more than half of the patients had an indwelling catheter at the time of the 3 week assessment. Pressure sores are considered avoidable, and reflect inadequate nursing care rather than a medical complication per se. Endocrine function could not be assessed at all centres for logistical reasons.

In order to control for acute injury severity, an acute injury composite was calculated representing risk of unfavourable outcome at 6 months. Acute GCS, pupillary reaction, presence of major extracranial injury, age, country and five CT-brain features contribute to this composite, which was calculated using the online calculator for the Corticosteroid Randomisation After Significant Head Injury (CRASH) acute prognostic model.13

Outcome at 1 year was measured using the Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended (GOSE),17 which has good inter-rater reliability17 and validity,18 and is an established measure of global outcome after TBI. For evaluation of associations with age and gender, and for logistic regression analyses, GOSE was dichotomised into ‘good’ (GOSE 5–8) and ‘unfavourable’ (GOSE 1–4) outcome, in accordance with the definition of ‘good’ and ‘unfavourable’ outcome used in the CRASH study,13 reflecting independence at home.

Statistical methods

Data are presented as frequencies or median and IQR. Analysis was performed with SPSS V.22. Univariate binary logistic regression analyses were performed where statistically appropriate, to explore associations with outcome. Fisher's exact test was used for variables where a logistic regression model was unresolvable due to a nominator of zero. Variables found to be significant (p<0.05) with univariate analyses were incorporated into a multivariate model using a backwards method, with a cut-off for rejection of variables from the model of p=0.10. Interaction between tracheostomy and body mass index (BMI) was evaluated with a quadratic interaction model.

Results

One hundred and fourteen patients were recruited, of whom 100 (88%) were alive and followed up to 1 year. Seven patients died during follow-up (1 before the 3 week assessment, another 4 before the 3 month assessment, 2 after that). A further seven patients were lost to follow-up (2 before the 3 week assessment, another 2 before the 3 month assessment, 3 after that). Patient characteristics were (median, IQR): age, 42 years (24–52), lowest unsedated GCS during the first 24 h, 5 (4–7), duration of ventilation 12 days (6.75–20). Eighty-six were men and 28 were women. Gender (χ2 p=0.81) and age (Mann-Whitney U test, p=0.26) were not associated with outcome. Medical complications were present for 68 patients when assessed 3 weeks after injury and for 45 patients 3 months after injury. Data are summarised in table 2 and figure 1.

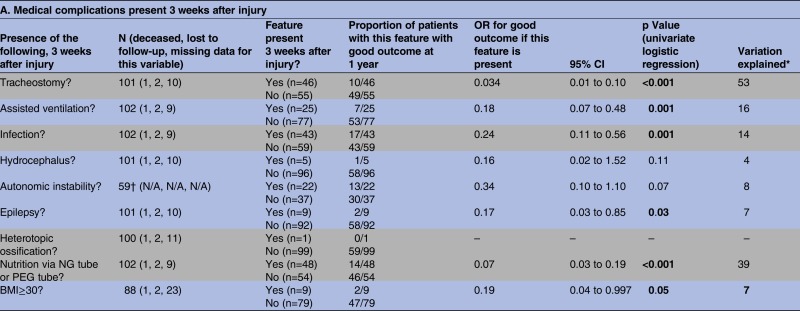

Table 2.

Variables negatively associated with good outcome 1 year after injury (Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended >4): univariate logistic regression analyses

|

*Variation explained=amount of variation explained by the model. (Model summary, Nagelkerke R2 SPSS ©).

†Assessable for patients without on-going infections, possible autonomic instability, see text.

–, No solution for logistic regression model due to nominator of 0; BMI, body mass index; N/A, not applicable; NG, nasogastric; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy.

Bold typeface indicates statistical significance at p<0.05.

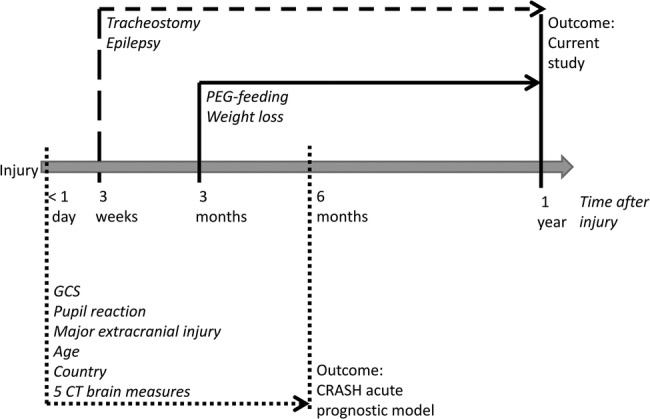

Figure 1.

Predicting outcome after severe traumatic brain injury (TBI): prognostic factors significant in multivariate models (CRASH, Corticosteroid Randomisation After Significant Head Injury; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastroscopy).

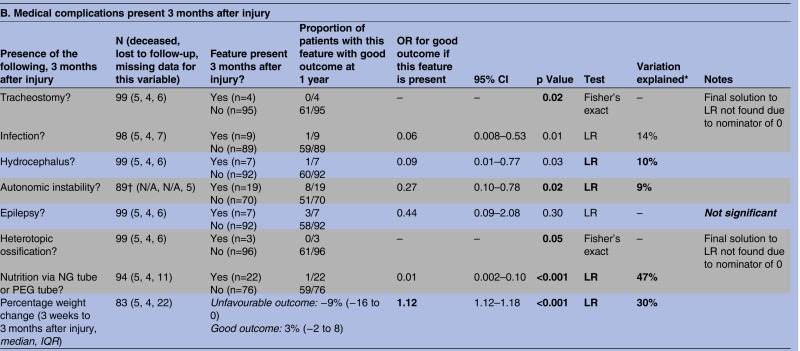

Table 2.

Continued

|

*Variation explained=amount of variation explained by the model. (Model summary, Nagelkerke R2 SPSS ©).

†Possible autonomic instability, patients without on-going infections, see text.

LR, logistic regression; N/A, not applicable; NG, nasogastric tube; PEG, percutaneous gastrostomy tube.

Bold typeface indicates statistical significance at p<0.05.

Medical complications present 3 weeks after injury

Univariate logistic regression analyses demonstrated that the following factors 3 weeks postinjury were associated with unfavourable outcome at 1 year: presence of a tracheostomy, assisted ventilation, infection, epilepsy, artificial nutrition via NG tube or PEG tube, BMI ≥30 (table 2A).

In order to explore further the possible association of early weight change on outcome at 1 year, we went on to attempt to extract BMI on admission from medical records. However, due to variability in timing of measurement of first weight after injury, and incomplete data on fluid balance at time of measurement, it was not possible to obtain reliable data for analysis.

For patients without on-going infection, markers of possible PSH at 3 weeks (in the form of tachycardia, hypertension or fever) showed a trend towards association with outcome at 1 year. Hydrocephalus was not significantly associated with outcome. Venous thromboembolism (no cases of pulmonary embolus and 2 cases of deep vein thrombosis) and heterotopic ossification (3 patients) occurred so rarely that associations with outcome could not be evaluated.

Medical features present 3 months after injury

Univariate logistic regression analyses demonstrated that the following factors 3 months postinjury were associated with unfavourable outcome at 1 year: infection, hydrocephalus, autonomic instability (possible PSH), artificial nutrition via PEG feeding tube, weight loss between 3 weeks and 3 months postinjury. Logistic regression models for presence of a tracheostomy tube and heterotopic ossification could not be resolved due to a nominator of zero. Fisher's exact test was therefore used, and demonstrated a significant association between these variables and unfavourable outcome. Only one patient remained on a ventilator at 3 months, so it was not possible to evaluate possible association with outcome for this variable (table 2B).

Multivariate logistic regression models

Model 1: associations between medical complications at 3 weeks and outcome

Those medical features at 3 weeks that had been shown with univariate analyses to have a significant association with unfavourable outcome were then incorporated into a multivariate model. Variables retained in the model were presence of a tracheostomy tube and epilepsy. OR for good outcome was 0.05 (CI 0.015 to 0.16, p<0.001) in the presence of a tracheostomy tube and 0.89 (CI 0.007 to 1.07, p=0.06) in the presence of epilepsy. Forty-eight per cent of the variation in the multivariate model was explained by these two variables.

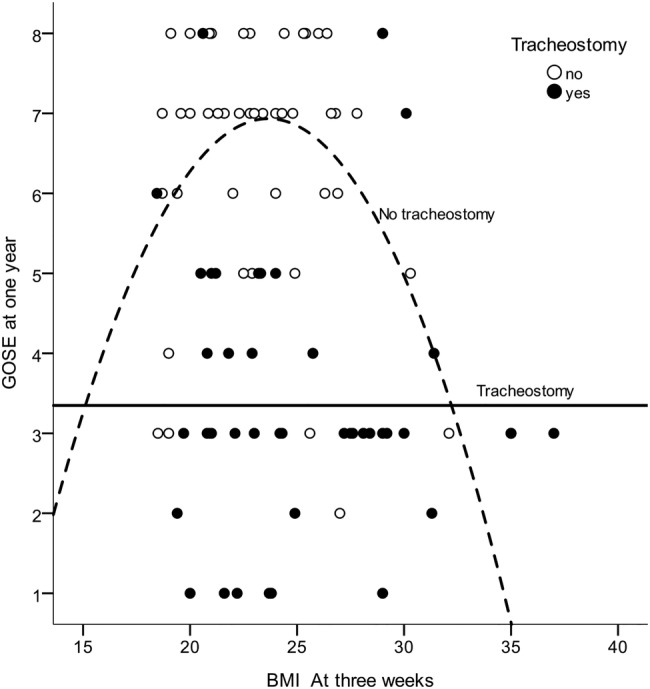

The effect of tracheostomy on outcome did not interact with the effect of ventilation (ie, the effect of tracheostomy was not significantly different for patients who had on-going ventilation). BMI was significantly different for patients with (mean BMI=25, SD=4.8) and without (mean BMI=23, SD=3.3) a tracheostomy (Student t test, equal variances not assumed, t=2.4, p=0.02), and as noted above, tracheostomy had a negative association with outcome. We went on to test for a possible mediation effect using a Sobel test, and found that the effect of BMI on outcome was in part mediated by presence of a tracheostomy (23%, p=0.05). It was also of interest to explore a possible interaction between BMI and tracheostomy, that is, whether the effect of BMI on outcome was different for patients with and without a tracheostomy. For this analysis, GOSE was treated as a continuous outcome measure (representing as it does a hierarchy of recovery, treatment of this categorical variable as continuous was judged reasonable). For patients with a tracheostomy there was no association, either linear, R2adj=−0.020, p=0.694, or curvilinear, R2adj=−0.044, p=0.888, between BMI and outcome. For patients without a tracheostomy, the association between BMI and outcome was curvilinear, R2adj=0.123, p=0.025 (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Association between body mass index (BMI) and outcome (Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended (GOSE)) at 1 year for patients who had (solid line) and did not have (dotted line) a tracheostomy at 3 weeks after injury.

In a previous study2 of the same cohort we found that within this group of severely injured patients, a relatively nuanced differentiation of prognosis based on acute injury variables (summarised by the CRASH composite incorporating acute GCS, pupillary reactions, extracranial injury, age, country and 5 acute CT-brain variables) did not significantly contribute to outcome prediction. As this finding was unexpected, and to avoid missing an important associations between acute injury severity and epilepsy or need for tracheostomy, we ran a further multivariate model incorporating acute injury severity (CRASH composite), tracheostomy at 3 weeks and epilepsy at 3 weeks. Findings were unchanged and acute injury severity was not retained in the model.

Model 2: relationships between medical features at 3 months and outcome

Features present later in the clinical course also have the potential to give prognostic information. Those medical features at 3 months that had been found to have a significant impact on outcome at 1 year with univariate logistic analyses were therefore incorporated into a separate multivariate model assessing later postacute prognostic factors. Variables present at 3 months that were entered into the model were thus: on-going infection, hydrocephalus, autonomic instability, nutrition via PEG feeding tube, percentage weight change. Features retained in the multivariate model were: on-going PEG feeding at 3 months and weight change from 3 weeks to 3 months together explaining 49% of the variation in the model. ORs for good outcome were for PEG feeding 0.04 (CI 0.004 to 0.31, p=0.002) and for weight change 1.07 (CI 1.0 to 1.13, p=0.048).

Discussion

Subacute complications occurred in two-thirds of patients. Presence of a tracheostomy tube and epilepsy at 3 weeks were associated with unfavourable outcome at 1 year, as were PEG feeding at 3 months, and weight loss between 3 weeks and 3 months. These were not simply later markers of acute brain injury severity or (for tracheostomy) need for ventilation. It remains to be elucidated as to whether these factors are primarily markers of later development of secondary brain injury (with resultant prolonged inability to maintain the airway or to feed orally), or of secondary systemic complications due to immobilisation and non-specific responses to severe injury.

Assessment of long-term prognosis after severe TBI could be considered an iterative process throughout the disease course, whereby past and current clinical data are continuously synthesised in order to make and update predictions of the likely long-term outcome. Ongoing refinements of predictions first made immediately after severe TBI could be possible on the basis of secondary insults and complications, variations in spontaneous recovery and response to rehabilitation. At the time of writing, such a continuous synthesis of information remains largely a matter of clinical experience and the accuracy of such prognostic predictions at different time points later after injury is largely unknown. Development of objective tools for refined outcome prediction at various points postinjury should be a focus for future studies.

The negative association of the presence of a tracheostomy at 3 weeks with outcome at 1 year, if confirmed by future studies, could be a simple clinical marker of use to guide rehabilitation and discharge planning, and also in discussions with families. A persistent need for a tracheostomy is a major sign of impairment of vital function and this finding thus has face validity. Possible explanations for this association remain speculative but encompass the following: (1) patients with tracheostomy at 3 weeks could have had more severe injuries initially, despite this not being captured by known acute prognostic markers summarised by the CRASH model; (2) continued presence of a tracheostomy could be a marker of secondary brain injury, possibly affecting the brain stem, and/or circuits mediating awareness and arousal,19 these affecting the patients’ ability to maintain an airway and clear secretions; and (3) a tracheostomy could be a marker of systemic effects of severe brain injury, related to both the need for ventilation, with associated risk for pneumonia, which may be recurrent, and via the effects of immobilisation and metabolic stress on respiratory muscle function. Impaired vital function and care logistics may both contribute to a delay in initiation of rehabilitation interventions. In short, a plethora of interacting factors could contribute to our findings. Multicentre studies are needed to analyse these further.

Patients noted to be obese at 3 weeks postinjury had less favourable outcomes, an effect mediated by the presence of a tracheostomy. Obese patients have an increased risk for sleep apnoea, and when immobilised have an increased risk for atelectasis and difficulty mobilising secretions. Association between high BMI and the need for tracheostomy thus has face validity.

Within the study design it was not possible to elucidate reasons for the association of epilepsy at 3 weeks on outcome, or to ascertain causality. The finding has, however, face validity: epilepsy could be a marker of continuing insults to the brain in the subacute period, such as difficulties controlling intracranial pressure. Alternatively, seizures during the first 3 weeks could themselves cause additional brain damage during a critical period of recovery. Further studies are needed.

Unfavourable outcome was very frequent in patients being fed via PEG tube 3 months post injury. PEG feeding at 3 months may thus be of value as a simple clinical prognostic marker in the postacute phase after injury. A prolonged need for PEG feeding likely reflects prolonged swallowing difficulties, and as such may be a postacute marker of brain injury severity. According to European guidelines,20 PEG feeding should be considered if the expected nutritional intake is likely to be qualitatively or quantitatively inadequate for 2–3 weeks. These guidelines seem reasonable in the absence of specific guidelines for patients after TBI.

Weight loss during the subacute period was also associated with unfavourable outcome. The importance of nutrition after TBI has previously been recognised, particularly regarding the hypercatabolic state that has been demonstrated to occur in many patients in the first 2 weeks after injury.21 Early feeding has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality,22 possibly by minimising effects of hypercatabolism on respiratory and other muscles. However, fewer data are available on time frames for recovery from this hypercatabolic state, on mechanisms leading to its possible persistence, or on the potential impact of interventions to optimise nutrition in the subacute phase on outcome.

Rates of VTE were low, based on clinically diagnosed VTE. Possible undiagnosed VTE cannot be ruled out. Use of low-molecular-weight heparin prophylaxis was widespread. A recent prospective study23 (n=36) using twice weekly ultrasound found VTE in a similar proportion of patients (6%), while a larger retrospective study24 found rates of 0.4–15%, with higher rates in patients with delayed initiation of VTE prophylaxis.

Limitations

Rehabilitation medicine in Sweden has traditionally focused on adults of working age, which is why we recruited patients aged 18–65 years. Recent reports25 have, however, emphasised the high rate of TBI in the elderly, and TBI is also an important cause of disability in children. Future studies should include these age groups.

Our definition of epilepsy did not expressly distinguish between early seizures (in the 1st week) and later seizures. Study clinicians were, however, familiar with the definition of post-traumatic epilepsy as recurrent late seizures (after the 1st week), and the risk that some patients recorded as having epilepsy at 3 weeks may have only had early seizures is considered low.

Within our study design, with assessments on single occasions, 3 weeks, 3 months and 1 year after brain injury, it was not possible to fully capture all aspects of PSH12 (hyperhidrosis, episodes of hypertension, rigidity, tachypnoea, tachycardia, decerebrate posture) optimally, due to their episodic occurrence. To establish a diagnosis of PSH also necessitates exclusion of other possible causes (eg, pain, other underlying medical complication). The absence of consensus regarding clinical diagnostic criteria made it impossible to ensure sufficiently high inter-rater reliability for diagnosis of PSH. Indeed, a recent review identified nine different diagnostic criteria for PSH in recent use.26 We did record pulse, blood pressure, temperature and muscle tone at each assessment, but not hyperhidrosis, tachypnoea or decerebrate posturing. Within the study design, and to keep the number of variables within practical limits for data collection, a complete assessment of all possible aspects of PSH was not possible. Recent publication of consensus diagnostic criteria9 and an assessment measure are important developments that await validation.

Conclusions

Subacute complications occurred in two-thirds of patients. Presence of a tracheostomy or epilepsy at 3 weeks had associations with unfavourable outcome at 1 year that were not explained by acute injury severity, as did PEG feeding and weight loss 3 months after injury. Further studies are recommended on larger cohorts to confirm these findings and to identify pathophysiological mechanisms that may be amenable to intervention. Data will also inform clinicians and healthcare planners developing optimal care pathways for patients after severe TBI.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and their relatives, the PROBRAIN collaborators, the clinical staff of their units, and their neurosurgical colleagues who allowed recruitment of their patients. They also thank Dr Anna Tölli, Danderyd Hospital and Karolinska Institute; Dr Kristina Lindgren, Karlstad Hospital; Dr Björn Johansson, University Hospital Uppsala, and Dr Christer Tengvar, University Hospital Uppsala, who assisted in assessment of patients. Paramedical staff contributing to the study included Stina Gunnarsson and Marina Byström Odhe, (Linköping), Anna-Lisa Nilsson (Umeå), Marie Sandgren (Stockholm), Staffan Stenson (Uppsala), and Siv Svensson (Gothenburg). Seija Lund was nurse coordinator in Stockholm and Ingrid Morberg in Gothenburg. Lisbet Broman gave previous advice on statistical aspects. Professor Richard Levi organised financial support in the Northern Region of Sweden. PROBRAIN collaborators: AKG, CND, Profesor Jörgen Borg, Department of Clinical Sciences, Karolinska Institute and University Department of Rehabilitation Medicine Stockholm, Danderyd Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden; Dr Marie Lindgren, Department of Clinical Rehabilitation Medicine, County Council, Linköping, Sweden; Dr Gudrun Karlsdottir, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Landspitalinn, University Hospital, Reykjavik, Iceland; Dr Maud Stenberg, Dr Britt-Marie Stålnacke and Professor Richard Levi, Norrlands University Hospital Umeå, Sweden; Dr Trandur Ulfarsson, MD, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden; and Dr Marianne Lannsjö, Department of Neuroscience, Uppsala University and Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Gävle and Sandviken Hospital, Sweden.

Footnotes

Contributors: AKG, MS, B-MS, KK and CND contributed to the design. AKG, MS, B-MS and CND contributed to the acquisition of data. AKG, CND, JJ, KK and KS contributed to the analysis and interpretation. AKG drafted the manuscript and all the authors revised it and approved the final version.

Funding: This study was supported by grant 060833 from AFA insurance (to Professor Jörgen Borg). AKG has received support from ALF-grants from Uppsala University Hospital and Danderyd Hospital. MS and B-MS have received ALF-grants from Umeå University Hospital.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was reviewed by the regional ethical review board in Stockholm, diary number 2009/1644–31/3.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available

References

- 1.Polinder S, Meerding WJ, Van Baar ME et al. Cost estimation of injury-related hospital admissions in 10 European countries. J Trauma 2005;59:1283–90. 10.1097/01.ta.0000195998.11304.5b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godbolt AK, Stenberg M, Lindgren M et al. Associations between care pathways and outcome 1 year after severe traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2014 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000050 [Epub ahead of print 4 Jun 2014]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katz DI, Polyak M, Coughlan D et al. Natural history of recovery from brain injury after prolonged disorders of consciousness: outcome of patients admitted to inpatient rehabilitation with 1–4 year follow-up. Prog Brain Res 2009;177:73–88. 10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17707-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenfeld JV, Maas AI, Bragge P et al. Early management of severe traumatic brain injury. Lancet 2012;380:1088–98. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60864-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andelic N, Bautz-Holter E, Ronning P et al. Does an early onset and continuous chain of rehabilitation improve the long-term functional outcome of patients with severe traumatic brain injury? J Neurotrauma 2012;29:66–74. 10.1089/neu.2011.1811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andelic N, Ye J, Tornas S et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) of an early-initiated, continuous chain of rehabilitation after severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2014;31:1313–20. 10.1089/neu.2013.3292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whyte J, Nordenbo AM, Kalmar K et al. Medical complications during inpatient rehabilitation among patients with traumatic disorders of consciousness. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013;94:1877–83. 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Specialist rehabilitation in the trauma pathway: BSRM core standards: British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine, 2013.

- 9.Baguley IJ, Perkes IE, Fernandez-Ortega JF et al. Paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity after acquired brain injury: consensus on conceptual definition, nomenclature, and diagnostic criteria. J Neurotrauma 2014;31:1515–20. 10.1089/neu.2013.3301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kammersgaard LP, Linnemann M, Tibaek M. Hydrocephalus following severe traumatic brain injury in adults. Incidence, timing, and clinical predictors during rehabilitation. NeuroRehabilitation 2013;33:473–80. 10.3233/NRE-130980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dizdar D, Tiftik T, Kara M et al. Risk factors for developing heterotopic ossification in patients with traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 2013;27:807–11. 10.3109/02699052.2013.775490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perkes I, Baguley IJ, Nott MT et al. A review of paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity after acquired brain injury. Ann Neurol 2010;68:126–35. 10.1002/ana.22066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perel PA. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: Practical prognostic models based on large cohort of international patients. Bmj 2008;336:425–9. 10.1136/bmj.39461.643438.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray GD, Butcher I, McHugh GS et al. Multivariable prognostic analysis in traumatic brain injury: results from the IMPACT study. J Neurotrauma 2007;24:329–37. 10.1089/neu.2006.0035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lingsma HF, Roozenbeek B, Steyerberg EW et al. Early prognosis in traumatic brain injury: from prophecies to predictions. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:543–54. 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70065-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Starmark JE, Stalhammar D, Holmgren E. The Reaction Level Scale (RLS85). Manual and guidelines. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1988;91:12–20. 10.1007/BF01400521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson JT, Pettigrew LE, Teasdale GM. Structured interviews for the Glasgow Outcome Scale and the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale: guidelines for their use. J Neurotrauma 1998;15:573–85. 10.1089/neu.1998.15.573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levin HS, Boake C, Song J et al. Validity and sensitivity to change of the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale in mild to moderate traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2001;18:575–84. 10.1089/089771501750291819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laureys S, Schiff ND. Coma and consciousness: paradigms (re)framed by neuroimaging. Neuroimage 2012;61:478–91. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loser C, Aschl G, Hebuterne X et al. ESPEN guidelines on artificial enteral nutrition—percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). Clin Nutr 2005;24:848–61. 10.1016/j.clnu.2005.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krakau K, Omne-Ponten M, Karlsson T et al. Metabolism and nutrition in patients with moderate and severe traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. Brain Inj 2006;20:345–67. 10.1080/02699050500487571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scrimgeour AG, Condlin ML. Nutritional treatment for traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2014;31:989–99. 10.1089/neu.2013.3234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Praeger AJ, Westbrook AJ, Nichol AD et al. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolus in patients with traumatic brain injury: a prospective observational study. Crit Care Resusc 2012;14:10–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reiff DA, Haricharan RN, Bullington NM et al. Traumatic brain injury is associated with the development of deep vein thrombosis independent of pharmacological prophylaxis. J Trauma 2009;66:1436–40. 10.1097/TA.0b013e31817fdf1c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Socialstyrelsen. Rehabilitering för personer med traumatisk hjärnskada (Rehabilitation for people with traumatic brain injury)—Landstingens rehabiliteringsinsatser, 2012:Report of the Swedish Board of Health and Welfare (in Swedish).

- 26.Perkes IE, Menon DK, Nott MT et al. Paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity after acquired brain injury: a review of diagnostic criteria. Brain Inj 2011;25:925–32. 10.3109/02699052.2011.589797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]