Abstract

Objectives

Current outcome measures in cardiac surgery are largely described in terms of mortality. Given the changing demographic profiles and increasingly aged populations referred for cardiac surgery this may not be the most appropriate measure. Postoperative quality of life is an outcome of importance to all ages, but perhaps particularly so for those whose absolute life expectancy is limited by virtue of age. We undertook a systematic review of the literature to clarify and summarise the existing evidence regarding postoperative quality of life of older people following cardiac surgery. For the purpose of this review we defined our population as people aged 80 years of age or over.

Methods

A systematic review of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, trial registers and conference abstracts was undertaken to identify studies addressing quality of life following cardiac surgery in patients 80 or over.

Results

Forty-four studies were identified that addressed this topic, of these nine were prospective therefore overall conclusions are drawn from largely retrospective observational studies. No randomised controlled data were identified.

Conclusions

Overall there appears to be an improvement in quality of life in the majority of elderly patients following cardiac surgery, however there was a minority in whom quality of life declined (8–19%). There is an urgent need to validate these data and if correct to develop a robust prediction tool to identify these patients before surgery. Such a tool could guide informed consent, policy development and resource allocation.

Keywords: GERIATRIC MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The studies included in our systematic review are largely retrospective in nature.

The majority of studies were of fair or poor quality as assessed by the US Preventative Services Task Force Quality Rating Criteria.

The studies did not provide sufficient quantitative data for meta-analysis.

Introduction

The two essential reasons to offer cardiac surgery are to improve quality of life (QoL) and prognosis. The latter probably becomes less important with increasing age. Useful preoperative risk calculators help surgeons estimate an individual's chance of death as a complication of planned cardiac surgery,1 but there is little to guide the likelihood of an improved QoL following surgery. This suggests that heart surgeons are falling short when seeking informed consent for their planned operations; especially so in the elderly where life's quality is likely to be valued over duration. This paper reviews the current literature on QoL following cardiac surgery in older participants. It provides a synthesis of evidence to identify gaps in our knowledge for new research, which is needed to inform patients as they consider consent for surgery and perhaps for health economists in resource allocation.

Methods

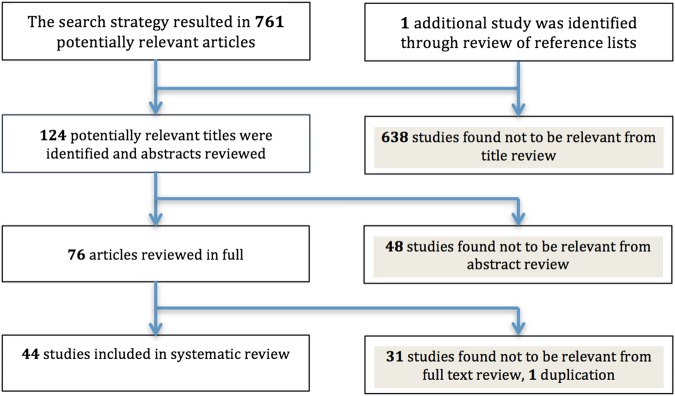

This systematic review was designed and reported following PRISMA criteria.2 Studies addressing QoL and functional status following cardiac surgery in patients aged 80 and over were identified by searching the electronic databases; MEDLINE (1950-22 February 2013, including articles in review stage), EMBASE (1980-22 February 2013) and the Cochrane Library (Issue 1 of 12 January 2013). A broad/sensitive search strategy was employed: truncated free-text searches within titles/abstracts/keywords were paired with exploded subject heading searches (MeSH and EMTREE). Search strategy/search terms used (TERMS IN CAPITALS are subject heading searches, ‘exp’ = exploded, MeSH terms given, equivalent EMTREE headings used in EMBASE): ‘“quality of life” OR qol’ in title/abstracts/keywords OR exp QUALITY OF LIFE/AND ‘(Heart* NEXT surg*) OR (heart* NEXT operat*) OR (cardi* NEXT surg*) OR (cardi* NEXT operat*)’ in title/abstracts/keywords OR exp CARDIAC SURGICAL PROCEDURES/OR THORACIC SURGERY/AND ‘8? NEXT yr? OR 8? NEXT year? OR 8?yr? OR 8?year? OR octagen* OR eighty NEAR/2 year? OR 9? NEXT yr? OR 9? NEXT year? OR 9?yr? OR 9?year? OR nonagen* OR ninety NEAR/2 year?’ OR AGED, 80 AND OVER in title/abstracts/keywords. All searches were completed on 22 February 2013. An advanced Google search, search of the National Health Service (NHS) Evidence portal (http://www.evidence.nhs.uk/), and the reference lists of articles were reviewed to check the rigour of the database search strategy. No language, publication date or publication status restrictions were imposed; however during the article review stage, manuscripts that were not in English language were excluded. Two reviewers (UA/MD) performed eligibility assessments independently in an un-blinded standardised manner. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus. Figure 1 details study selection.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of study selection.

Data collection process

A data extraction sheet was pilot tested on the first 10 studies identified and refined accordingly. Information was extracted from each study on: (1) characteristics of study participants (2) type of operation and (3) QoL outcome measure employed. The quality of evidence was assessed using the US Preventative Services Task Force Quality Rating Criteria3 (USPSTFQR).

Quality of life assessment tools

The primary outcome measure was QoL of octogenarians (>80 years) following cardiac surgery. Assessment tools in the identified studies ranged from established QoL measures to bespoke questionnaires and objective assessments of independence, including physical functioning and activities of daily living. Of the validated tools used, the Medical Outcome Study Short Form-36 questionnaire (SF-36)4 and Karnofsky performance status score5 were most commonly employed. The SF-36 is validated for the assessment of QoL in multiple disease states including cardiovascular disease and elderly populations.6 Introduced in 19907 and upgraded to V.2 in 1996,8 the questionnaire consists of 36 questions covering 8 domains (physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional and mental health), scaled from 0 to 100, a higher score indicates a better QoL. The domains are summarised into physical and mental health scores. The SF-12 is a shortened version covering the same eight domains. The Karnofsky score addresses functional impairment and was originally designed to assess overall performance status in patients with cancer. It is scored in 10% increments; from normal activity (100%), through to death at 0%. Other QoL and functional measures employed throughout the literature include; the Seattle Angina Questionnaire9 and Barthel Index,10 Nottingham Health profile,11 EQ-5D-3L12 Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS),13 Swedish health-related quality of life survey (SWED-QUAL)14 and the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ).15

Results

Forty-four studies were identified that reported the QoL of octogenarians following cardiac surgery. Eight of the studies reported functional status as a measurement of QoL; these studies are included in our results (table 1). Twenty-three studies originated from Europe, 10 from the USA, 7 from Canada, 3 from Australia and 1 from Japan. The mean age of study participants ranged from 81 to 86.5 years and the study size from 21 to 1062 participants. Thirty-six of the 44 studies reported preoperative comorbidities but significant variation of conditions reported prevents meaningful comparison. The majority of studies were retrospective, however, nine studies followed patients prospectively allowing for direct comparison before and after surgery.

Table 1.

Prospective studies

| Reference study type (quality of study: USPSTFQR score) | Surgery: average age | Number in study (survivors, % assessed for QoL) | QoL tool | Length of follow-up | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olsson et al16 Prospective (Fair quality) Stockholm, Sweden |

AVR Mean 83±2 |

32 (25, 96%) | Self-designed questionnaire | 3 and 12 months | Physical ability improved, depression decreased, improvement in self-rated health |

| Deutsch et al17 Prospective (Conference abstract) Munchen, Germany |

All cardiac surgery Median 82.5 (80–91.8) |

87 (Not specified) | SF-36 | 3 months | The SF-36 scores for physical functioning (41.8 vs 48.7, p=0.05), role-physical (25.8 vs 36.4, p=0.05), bodily-pain (51.9 vs 74.4, p=0.001) and vitality (41.2 vs 49.8, p=0.006) increased 3 months postoperatively. No significant differences found for general health (54.3 vs 56.6, p=0.38), mental health (67.9 vs 71.8, p=0.1) role-emotional (59.5 vs 60.5, p=0.9), social functioning (75.4 vs 73.6, p=0.63) scores |

| Ferrari et al18 Group 1: Retrospective Group 2: Prospective (Conference abstract) Modena, Italy |

All cardiac surgery Not documented |

Group 1: 192 Group 2: 21 (Not specified) |

SF-36 HADS SAQ |

Group 1: 5–7 years Group 2: not specified |

Group 1: satisfaction with treatment in 80%, freedom from cardiac symptoms in 62% and overall well-being in 78% of cases. Group 2: improvement of QoL (SF-36 mean total score 57.1 vs 73.5, p=0.001), clinical conditions and anxiety-depressive symptoms (p=0.001 both for HADS-anxiety and HADS-depression) |

| Pontoni et al19 Group 1: Retrospective Group 2: Prospective (Conference abstract) Modena, Italy |

All cardiac surgery Not documented |

Group 1: 86 Group 2: 21 (Not specified) |

SF-36 HADS SAQ |

Group 1: Mean 5.5 years Group 2: 6 months |

Group 1: Retrospective analysis: absence of physical limitation in 50% of patients, treatment satisfaction in 80%, satisfactory well-being and enjoyment of life in 78% Group 2: QoL showed significant improvement in 4 of 5 modified SAQ domains (except of treatment satisfaction), 6 of 8 SF-36 domains (except of Emotional Role Limitation and Vitality) and in depression and anxiety HADS subscales |

| Oldroyd et al20 Prospective (Conference abstract) Victoria, Australia |

All cardiac surgery Mean 83.2±2.5 |

63 (Not specified) | SF-36 | 3 months | 51(81%) felt that cardiac surgery had been worthwhile, despite no significant change in SF-36 scores |

| Lam et al21 Prospective (Poor quality) Ontario, Canada |

AVR±CABG Mean 83.7±3.4 (80–96) |

58 (20, 35%) | SF-36 | 6 months | Better scores for bodily pain, vitality, social functioning and mental health than patients <80. Better scores for bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning and mental health than the general population >75 |

| Wilson et al22 Prospective (Fair quality) New York, USA |

CABG Mean 82 (80–88) |

73 (71, 97%) | Karnofsky performance score | Up to 5 years | Karnofsky performance score improved from a mean 67 to 78 (p<0.05), median of 50–80. 83% independent of ADLs. 97% living at home |

| Khan et al23 Prospective (Fair quality) San Francisco, USA |

Valve surgery±CABG Mean 83.5 (80–89) |

61 (54, 100%) | Karnofsky performance score | 1 and 3 months | Median Karnofsky score increased from 30% to 80% 1 month post-operatively, sustained at 3-month follow-up |

| Glower et al24 Prospective (Fair quality) North Carolina, USA |

CABG Mean 81±2 (80–93) |

86 (74, 100%) | Karnofsky performance score | QoL data at discharge Mean 17±17 months | Median Karnofsky score improved from 20% to 70% (p=0.0001) Mean Karnofsky score improved from 27±15 preoperatively to 60±27% |

ADL, activities of daily living; AVR, aortic valve replacement; CABG, coronory artery bypass graft; HADS, Hospital anxiety and depression scale; QoL, quality of life; SAQ, Seattle Angina Questionnaire; SF-36, Short Form 36.

Prospective studies

Nine prospective studies were identified, five studies employed the SF-36, three the Karnofsky score and one used a self-designed questionnaire (table 1). These studies included 780 patients, with an age range of 80–96. Length of follow-up varied from 3 months to 7 years. Those studies employing the SF-36 and one self-designed questionnaire16 found generally an overall improvement after surgery,17–19 with one study demonstrating no significant difference at 3 months.20 Domains that significantly improved varied between studies. Superior SF-36 scores were also found when comparing octogenarians to a younger cohort and an age-matched general population.21 The three studies using Karnofsky score22–24 found significant improvement in functional status following surgery.

Retrospective studies

Thirty-five retrospective studies were identified and five used multiple QoL tools (table 2). These studies included 8456 patients, with an age range of 80–99 and length of follow-up that varied from 6 months to 11.8 years. The tools employed in these studies included SF-36 in 10 studies, SF-12 in 3, self-designed questionnaires in 11, Karnofsky performance score in 4, SAQ in 4, Barthel index in 3, SWED-QAL 2, EQ-5D in 1, Nottingham Health Index in 1 and MLHFQ in 1. Eleven studies compared QoL following cardiac surgery to an age-matched cohort of the general population. Nine studies found comparable or superior QoL scores for the study population in most domains.25–33 One study found lower scores in the physical domains of the study population.34 Two studies reported poorer outcomes in women,35 36 however a third paper revealed the opposite.29 Three studies compared postoperative QoL in octogenarians against a younger patient cohort. While the first found superior SF-36 scores in the majority of domains37 the second found inferior SF-12 summary scores in the octogenarian cohort38 and the third found significantly lower physical function and the physical component summary scores in octogenarians.39 Two studies asked patients for their subjective comparison of QoL following surgery with that before. Both found a general improvement in QoL after surgery,40 although the second found a 33% reduction in physical fitness.41 The Seattle Angina Questionnaire was used to report QoL in three studies41–43 and reported that the majority of patients had a good functional status following surgery and were satisfied with their QoL. Eleven studies employed self-designed questionnaires, reporting an improvement in QoL in the majority of patients.44–54 However, in a small but significant minority QoL decreased following surgery. One study reported that QoL worsened in 12%,46 a second found a reduction in 15%,47 a third study reported that 17.8% felt their autonomy was worse following surgery48 and a forth reported that 13.2% felt their dependence on social support had increased. Interestingly, at 1 month following surgery 43% would not recommend surgery. This fell to 14% at 1 year.49 In one study multivariate analysis revealed female gender to be the only predictor of impaired autonomy50 and a second found poor left ventricular ejection fraction was an independent factor reducing QoL.44 Lower QoL scores in females were also demonstrated in one study employing the Nottingham Health profile54 Five studies employed the Karnofsky and/or Barthel Index to report the functional status of octogenarians following cardiac surgery and found an improvement in the majority of patients.55–59

Table 2.

Retrospective studies

| Reference study type (quality of study: USPSTFQR score) | Surgery: average age | Number in study (survivors, % assessed for QoL) | QoL tool | Length of follow-up | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruitman et al25 Retrospective (Fair quality) Nova Scotia, Canada |

All cardiac surgery Mean 83±2.5 (80–92) |

127 (103, 96.1%) | SF-36 SAQ |

Mean 15.7 (4.7–27.7) months | SF-36 scores were equal to or better than those for the general population 83.7% living in their own home, 74.8% rated their health, as good or excellent, 82.5% would undergo operation again |

| Kurlansky et al26 Retrospective (Good quality) Florida, USA |

CABG Mean 83.1±2.8 (80–99) |

1062 (555, 98.2%) | SF-36 | Mean 3.4 (0.1–12.6) years | SF-36 scores comparable to age-adjusted norms in mental and physical summary scores |

| Sjogren et al27 Retrospective (Fair quality) Lund, Sweden |

All cardiac surgery Mean 81.8±2.3 (80–91) |

117 (41, 95%) | SF-36 | Mean 8.3 ±1.9 years | QoL comparable to age-matched population, lower physical function, but less bodily pain in study population |

| Vicchio et al

28 Retrospective (Fair quality) Naples, Italy |

AVR± CABG BP: Mean 82.9±2.7 MP: Mean 81.8±1.8 |

160 (125, 97.6%) | SF-36 | Mean 3.4±2.8 years | Scores higher than age-matched and sex-matched Italian population in all domains other than vitality |

| Collins et al29 Retrospective (Fair quality) Stockholm, Sweden |

All cardiac surgery Mean 81.9±1.3 (80–84) |

183 (155, 94.2%) | SWED-QUAL | 1–6 years | Patients had significantly better physical functioning, satisfaction with physical functioning, relief of pain and emotional well-being (p=0.01) compared to the normal population |

| Kurlansky et al30 Retrospective (Good quality) Florida, USA |

CABG (Arterial vs SVG) SVG: Mean 83.5±3.0 (80–99) ART+SVG: Mean 82.5±2.5 (80–92) |

987 Arterial (247/97%) SVG (247/98.8%) |

SF-36 | Arterial 3.8 years (0.4–12.6) SVG 3.1 (0.2–11.2) |

Patients with arterial grafts scored significantly higher than SVG patients and age-adjusted normal participants |

| Ghanta et al31 Retrospective (Good quality) Massachusetts, USA |

CABG, AVR±CABG Mean 82 (80–94) |

459 (158, 72%) | SF-12 | Median 7.9 years | Survivors’ median quality of life mental health score was higher (55.2 vs 48.9; p<0.05) and physical health score was equivalent (39.3 vs 39.8; p=0.66) to the general elderly population |

| Krane et al32 Retrospective (Fair quality) Munich, Germany |

CABG, AVR±CABG Mean 82.3 (80–94) |

1003 (514, 75.1%) | SF-36 | Mean 3.62±2.42 years | Physical functioning 49.7; role-emotional 58.5; social functioning 76.2; mental health 69.7, bodily pain 70.5, vitality 48.7, role-physical 43.6, general health 55.5. Bodily pain, general health higher than age-matched population (p<0.01). Role-physical and role-emotional lower (p<0.02) Summarised physical health score increased (p<0.05) compared with the general population, the mental health summarised scores showed no difference |

| Sundt et al33 Retrospective (Fair quality) St Louis, USA |

AVR±other cardiac procedure Mean 83.5±2.6 (80.1–90.6) |

133 (65, 98%) | SF-36 | Up to 5 years | SF-36 scores comparable to general population >75. Participants scored higher than the control population in 5 areas; bodily pain, general health, social functioning, role-emotional and mental health |

| Schonebeck et al34 Retrospective (Conference abstract) Hamberg, Germany |

All cardiac surgery Mean 82±2.5 |

107 (Not specified) | SF-36 | Not specified | Lower scores for physical functioning (37±10.5), general health (44.1±11.0), physical role (41.0±7.8), and physical component summary (44.7±9.3) compared to the normal population (p=0.001) |

| Ghosh et al35 Retrospective (Fair quality) Salzburg, Austria |

All cardiac surgery Mean 82.2±1.8 |

212 (186, not specified) | EQ-5D | Mean 40.2 (2–144) months | Concluded excellent postoperative QoL. Mean EQ-5D score of 6.5. Score slightly poorer in women (6.7), than men (6.2) |

| Spaziano et al36 Retrospective (Fair quality) Quebec, Canada |

Valve replacement Mean 82 (80–89) |

133 (118, 64.4%) | SF-12v2 MLHFQ |

Mean 2.0±1.1 years | Men similar to age-matched population. Women similar in physical component scale but lower mental component. Data from MLHFQ revealed worse QoL in females than in males, both on the physical and emotional scales |

| Aboud et al37 Retrospective (Fair quality) Jena, Germany |

AVR Not documented |

<53 (Not specified) | SF-36 | Mean 21.4 months (18–24) |

SF-36 scores better in bodily pain, mental health, social functioning, role emotional in patients >80 |

| Sen et al38 Retrospective (Good quality) Giessen, Germany |

CABG Mean 82.3±2.13 |

240 (97.1%) | SF-12 | Mean 53 months | Four years after surgery, 95.2% of the octogenarians lived alone, with a partner or with relatives, and only 4% required permanent nursing care. 83.9% of the octogenarians would recommend surgery to their friends and relatives for relief of symptoms. Mental component scores higher than physical component scores and overall summary scores lower than in a younger age group |

| Nydegger et al39 Retrospective (Conference abstract) Zurich, Switzerland |

All cardiac surgery Mean 82.2±2.7 |

53 (Not specified) | SF-36 | 1 year | Physical function (p=0.002) and the physical component summary (p=0.03) were lower in patients >80. The mental component summary was similar between both groups (compared with patients <80) |

| Levin et al40 Retrospective (Poor quality) Lund, Sweden |

AVR±CABG >85 Mean 86.5±1.5 (85–91) |

21 (13, 100%) | SWED-QUAL | 9–83 months | Significant improvement in physical functioning, satisfaction with physical ability, sleep, health status and perception of general health |

| Folkman et al41 Retrospective (Fair quality) Vienna, Austria |

AVR±CABG Mean 82.9±2.5 |

154 (126, 100%) | SAQ | 1 year | Improvement in QoL in 96% reduction in physical fitness in 33% |

| Huber et al42 Retrospective (Fair quality) Inselspital, Switzerland |

CABG, AVR±CABG Mean 82.3±2.1 (80–91) |

136 (120, 100%) | SAQ | Mean 890 (69–1853) days | 81% had no or ‘little’ disability in ADL, 65% very satisfied with QoL |

| Graham et al43 Retrospective (Fair quality) Calgary, Canada |

CABG (compared with PCI and medical mx) Median 81.8 |

66 at 1 year 55 at 3 years |

SAQ | At 1 and 3 years | All domains (angina stability, angina frequency, QoL, treatment satisfaction) other than exertional capacity significantly better with CABG than medical management, at both 1 and 3 years |

| Kamiya et al44 Retrospective (Poor quality) Tokyo, Japan |

CABG+PCI Mean 82.1±2.1 |

28 (15, 100%) | Self-designed based on SAQ | Mean 39.9±30.1 months | 80% no limitation dressing, 66.7% no or little limitation walking 300 m, 86.7% satisfied with their treatment |

| Nikolaidis et al45 Retrospective (Fair quality) Southampton, UK |

AVR±CABG Mean 82.9±2.3 |

345 (279, 62%) | Self-designed questionnaire | Mean 39.3±29 months | 83.7% satisfied with operation outcome, 82% independent personal care, 88.3% had positive feelings about life |

| Tsai et al46 Retrospective (Fair quality) California, USA |

All cardiac surgery Mean 83.1±2.7 (80–94) | 528 (Not specified) | Self-designed questionnaire | 6 months | 70% improved QoL, 18% same, 12% worse. 38% active lives, 26% sedentary, 35% restricted |

| Schmidtler et al47 Retrospective (Good quality) Munich Germany |

All cardiac surgery Mean 82.6±2.9 (80–93) |

641 (227/90%) | Self-designed questionnaire | Mean 3.6 (0.1–11.8) years | At mid-term follow-up QoL had improved in 54%, there was no difference in 31% and was impaired in 15%. 80% of all surviving patients lived in their own home |

| Maillet et al48 Retrospective (Fair quality) Saint-Denis, France |

AVR±CABG Mean 83.7±3.3 (80–94) |

84 (51/100%) | Self-designed questionnaire | Mean 723±404 days | 91.1% living in their own homes, Self-rated health ‘excellent’ or ‘good’ in 76.8%, 66.1% reported health had improved postoperatively, 60.7% would have operation again, 26.7% required help for ADL. 17.8% felt autonomy was worse postoperatively |

| Goyal et al49 Prospective (Fair quality) Victoria, Australia |

All cardiac surgery Mean 82.4 (80–94) |

100 (80,85%) | Self-designed questionnaire | 6–60 months | 86.76% were less dependent on others, 13.23% felt their dependence on social support had increased, 80.9% were feeling well and looking positively to the future, 94.2% patients would have the procedure again, in retrospect, 41.2% lived alone |

| Kirsch et al50 Retrospective (Fair quality) Creteil, France |

All cardiac surgery Mean 83±2.7 (80–91) |

191 (129, 97%) | Self-designed questionnaire | Mean 22.24 (0–73.3) months | 64% of long-term survivors fully autonomous, female sex only independent predictor of impaired autonomy, 83% satisfied with QoL |

| Kolh et al51 Retrospective (Fair quality) Liege, Belgium |

AVR Mean 82.8±2.4 (80–94) |

220 (59%) | Self-designed questionnaire | Mean 58.2 months | 91% believed that having heart surgery after age 80 years was a good choice, and similarly 88% felt as good as or better than they had preoperatively |

| Hewitt et al52 Retrospective (Fair quality) Perth, Australia |

All cardiac surgery Mean 8.13±1.2 (80–88) |

64 (44/100%) | Modified SF-36 (16 questions) | 1 month, 1 year, final+mean 2.8±0.8 years | 98% thought surgery was worthwhile and would recommend to a friend and 86% were living independently |

| Diegeler et al53 Retrospective (Fair quality) Gottingen, Germany |

All cardiac surgery Mean 82.2±1.79 (80–87) |

54 (43, 100%) | Self-designed questionnaire | Mean 26.2±16.54 (6–91) months | Of 43 survivors 41 lived independently, 38 capable of ADLs without help. 40 of the 43 survivors described significant improvement in their QoL |

| Ennker et al54 Retrospective (Fair quality) Baden, Germany |

Stentless AVR Mean 82±2 |

76 (Not specified) | Nottingham health profile | Mean 35±23 months | QoL equal to or better than general population. Women had slightly lower QoL than men |

| Kumar et al55 Retrospective (Fair quality) Baltimore, USA |

All cardiac surgery Group 1 Mean 83.2±2.2 (80–87) Group 2 Mean 83.0±2.0 (80–89) |

Group 1:15 (8/100%) Group 2: 52 (38/100%) |

Karnofsky performance score Self-designed questionnaire |

Mean 1.5 years | Improvement in QoL, 75% group 1 and 84% group 2, would have operation in retrospect. Mean Karnofsky dependency category decreased from 2.0±0.4 to 1.5±0.5 p<0.01 |

| NNwaejike et al56 Retrospective (Fair quality) Maryland, USA |

All cardiac surgery Mean 82.4±1.28 (80–88) |

66 (Not specified) | Barthel Index | Not specified | Mean Barthel Index 17.7 (min 0, max 20) |

| Chaturvedi et al57 Retrospective (Good quality) Quebec, Canada |

All cardiac surgery Mean 82.5 (80–92) |

300 (188, 100%) | Barthel Index Karnofsky performance score |

Up to 5 years | At 3.6 years: 64.9% autonomous, 28.1% semiautonomous, and 9.2% dependent. 71.8% were at home, 21.2% in a residence, and 6.9% in a supervised setting |

| Leung et al58 Retrospective (Fair quality) Quebec, Canada |

Valve surgery±CABG Mean 8.5 (80–92) |

185 (110, 100%) | Karnofsky performance score Barthel Index |

Mean 38 (7–78) months | 66% autonomous, 26% semiautonomous, 8% dependent 72% living at home, 19% in residence, 9% in a supervised nursing facility |

| Caus et al59 Retrospective (Fair quality) Ottawa, Canada |

AVR Not documented |

101 (61, not specified) | Karnofsky performance score | Mean 2.7 years per patient | Mean Karnofsky score 61 |

ADL, activities of daily living; AVR, aortic valve replacement; CABG, coronory artery bypass graft; MLHFQ, Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; QoL, quality of life; SAQ, Seattle Angina Questionnaire; SF-36, Short Form 36; SVG, Saphenous vein grafts; SWED-QUAL, The Swedish health-related quality of life survey.

Discussion

This systematic review was constructed according to the PRISMA guidelines. A comprehensive search strategy of the key medical electronic databases identified 44 studies. These included 9236 patients in total and all studies were retrospective but for 9. There was marked heterogeneity between studies. In general both prospective and retrospective series indicated an improvement in postoperative QoL for the majority of patients or a postoperative QoL comparable to an age-matched general population. Established tools used in measurement of QoL and functional status are validated and well designed. Self-designed questionnaires, though not validated, identified a significant minority in whom QoL fell after surgery (8–19%). Variable results may reflect different populations studied and individual centre's selection bias for surgery, as well as disparities in measurement methods. One key difference is the inclusion of a value for death, as overall results will differ if death is accounted for rather than excluded. The Karnofsky Performance Score and EQ-5D include a score for death. Only one of the seven studies employing these tools attributed a score for death.22 Another key factor affecting QoL after surgery is the time at which it was measured. It is inevitable that QoL worsens immediately following surgery and hopefully improves as the patient recovers. However, while there is evidence of improvement over the first postoperative year,49 a number of studies detailing QoL at multiple time points found no significant interval change.16 23 In our analysis there is insufficient evidence to describe the postoperative pattern of QoL. The key finding of this review is the apparent decrease in QoL in 8–19% of octogenarians following cardiac surgery. It is essential to validate this finding and to identify these patients so that at worst, harm to their well-being can be avoided and at best, we can better understand who these individuals are. A prediction model for postoperative QoL is required to allow clinicians to select and help patients better understand the consequences of their heart surgery and hence improve the quality of patients’ informed consent.

Conclusion

QoL following cardiac surgery in octogenarians improves in the majority of patients. However some 8%–19% appear to experience a fall in QoL and regret their decision to go forward with heart surgery. Considering the expanding numbers of elderly patients in contemporary practice, it is desirable to identify patients who will not enjoy an improvement in QoL. At a population level such work may also inform the appropriate provision of limited healthcare resources. A prediction model for postoperative QoL is required to help patients better understand the consequences of surgery, and hence improve the quality of their informed consent.

Acknowledgments

Adam Tocock and Jessica Wilkin.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Andrew Cook at @ajcook

Contributors: SL, UA contributed to the conception and design of the work and acquisition of data. UA, SL, MD are responsible for the initial drafting of the manuscript. AC, CB, SH, LV contributed to data analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and provided final approval of version to be published.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Nashef SA, Roques F, Sharples LD et al. EuroSCORE II. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012;41:734–44; discussion 744–5 10.1093/ejcts/ezs043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. , The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:1006–12. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH et al. , Methods Work Group, Third U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Current Methods of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; a review of the process. Am J Prev Med 2001;20:21–35. 10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00261-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short form health survey (SF- 36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83. 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In: MacLeod CM, ed. Evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents. New York: Columbia University Press, 1949:196. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner-Bowker DM, Bartley PJ, Ware JE. SF-36® Health Survey & “SF” Bibliography: Third Edition (1988–2000). Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart AL, Ware JE. Measuring functioning and well-being: the medical outcomes study approach. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE. How to score version two of the SF-36 health survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric, Incorporated, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spertus JA, Winder JA, Dewhurst TA et al. Development and evaluation of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire: a new functional status measure for coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995;25:333–41. 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00397-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel index. Md State Med J 1965;14:61–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunt SM, McEwen J, McKenna SP. Measuring health status: a new tool for clinicians and epidemiologists. J R Coll Gen Pract 1985;35:185–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.EuroQol Group. EuroQol––a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brorsson B, Ifver J, Hays RD. The Swedish health-related quality of life survey (SWED-QUAL). Qual Life Res 1993;2:33–45. 10.1007/BF00642887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rector TS.2005. Overview of the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire. Internet. http://www.mlhfq.org/

- 16.Olsson M, Janfjall H, Orth-Gomer K et al. Quality of life in octogenarians after valve replacement due to aortic stenosis: a prospective comparison with younger patients. Eur Heart J 1996;17:583–9. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a014912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deutsch MA, Krane M, Schneider L et al. Prospective assessment of quality of life in patients aged 80 years and older undergoing cardiac surgery. Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgeon. 58. (conference abstract), 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrari S, Pontoni G, Gabbieri D et al. Feasibility of assessing quality of life in over-80 patients undergoing cardio-surgery. J Psychosom Res 2011;70:591–2. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pontoni G, Ferrari S, Gabbieri D et al. Quality of life assessment after cardiac surgery in octogenarians: is it really feasible? Eur Psychiatry 2011;26(Suppl 1):1974. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oldroyd J, Levinson M, Stephenson G et al. Cardiac surgery in octogenarians results in subjective gains but no objective improvements in quality of life or functional status after three months. Heart Lung Circ 2011;20:S224 10.1016/j.hlc.2011.05.550 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lam BK, Hendry PJ. Patients over 80 years: quality of life after aortic valve replacement. Age Ageing 2004;33:307–14. 10.1093/ageing/afh014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson MF, Baig MK, Ashraf H. Quality of life in octogenarians after coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol 2005;95:761–4. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan JH, McElhinney DB, Hall TS et al. Cardiac valve surgery in octogenarians: improving quality of life and functional status. Arch Surg 1998;133:887–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glower DD, Christopher TD, Milano CA et al. Performance status and outcome after coronary artery bypass grafting in persons aged 80 to 93 years. Am J Cardiol 1992;70:567–71. 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90192-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fruitman DS, MacDougall CE, Ross DB. Cardiac surgery in octogenarians: can elderly patients benefit? Quality of life after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;68:2129–35. 10.1016/S0003-4975(99)00818-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurlansky PA, Williams DB, Traad EA et al. Eighteen-year follow-up demonstrates prolonged survival and enhanced quality of life for octogenarians after coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;141:394–9. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sjogren J, Thulin LI. Quality of life in the very elderly after cardiac surgery: a comparison of SF-36 between long- term survivors and an age-matched population. Gerontology 2004;50:407–10. 10.1159/000080179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vicchio M, Della Corte A, De Santo LS et al. Tissue versus mechanical prostheses: quality of life in octogenarians. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:1290–5. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.12.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collins SM, Brorsson B, Svenmarker S et al. Medium-term survival and quality of life of Swedish octogenarians after open-heart surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2002;22:794–801. 10.1016/S1010-7940(02)00330-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurlansky PA, Williams DB, Traad EA et al. Arterial grafting results in reduced operative mortality and enhanced long-term quality of life in octogenarians. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;746:418–27. 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)00551-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghanta RK, Shekar PS, McGurk S et al. Long-term survival and quality of life justify cardiac surgery in the very elderly patient. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;92:851–7. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.04.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krane M, Voss B, Hiebinger A et al. Twenty years of cardiac surgery in patients aged 80 years and older: risks and benefits. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;91:506–13. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.10.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sundt TM, Bailey MS, Moon MR et al. Quality of life after aortic valve replacement at the age of >80 years. Circulation 2000;102:70–4. 10.1161/01.CIR.102.suppl_3.III-70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schonebeck J, Baustian S, Gulbins H et al. Quality of life of octogenarians after cardiac surgery. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;59:V102. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghosh P, Djordjevic M, Schistek R et al. Does gender affect outcome of cardiac surgery in octogenarians? Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2003;11:28–32. 10.1177/021849230301100108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spaziano M, Carrier M, Pellerin M et al. Quality of life following heart valve replacement in the elderly. J Heart Valve Dis 2010;19:524–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aboud A, Breuer M, Bossert T et al. Quality of life after mechanical vs. biological aortic valve replacement. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2009;17:35–8. 10.1177/0218492309102522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sen B, Niemann B, Attmann T et al. Long term outcomes and quality of life in octogenarians after coronary artery surgery. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;59:V103 10.1055/s-0030-1250635 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nydegger M, Boltres A, Graves K et al. Quality of life after cardiac surgery in an octogenarian population. Crit Care 2011;15:S4–5. 10.1186/cc9432 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levin II, Olivercrona GK, Thulin LI et al. Aortic valve replacement in patients older than 85 years: outcomes and the effect on their quality of life. Coron Artery Dis 1998;9:373–80. 10.1097/00019501-199809060-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Folkman S, Gorlitzer M, Weiss G et al. Quality-of-life in octogenarians one year after aortic valve replacement with or without coronary artery bypass surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2010;11:750–3. 10.1510/icvts.2010.240085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huber CH, Goeber V, Berdat P et al. Benefits of cardiac surgery in octogenarians—a postoperative quality of life assessment. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007;31:1099–105. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.01.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Graham MM, Norris CM, Galbraith PD et al. Quality of life after coronary revascularization in the elderly. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1690–8. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kamiya M, Takayama M, Takano H et al. Clinical outcome and quality of life of octogenarian patients following percutaneous coronary intervention or surgical coronary revascularization. Circ J 2007;71:847–54. 10.1253/circj.71.847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nikolaidis N, Pousios D, Haw MP et al. Long-term outcomes in octogenarians following aortic valve replacement. J Card Surg 2011;26:466–71. 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2011.01299.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsai T, Chaux A, Matloff JM et al. Ten-year experience of cardiac surgery in patients aged 80 years and over. Ann Thorac Surg 1994;58:445–51. 10.1016/0003-4975(94)92225-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmidtler FW, Tischler I, Lieber M et al. Cardiac surgery for octogenarians-a suitable procedure? Twelve-year operative and post-hospital mortality in 641 patients over 80 years of age. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008;56:14–19. 10.1055/s-2007-965642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maillet JM, Somme D, Hennel E et al. Frailty after aortic valve replacement (AVR) in octogenarians. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2009;48:391–6. 10.1016/j.archger.2008.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goyal S, Henry M, Mohajeri M. Outcome and quality of life after cardiac surgery in octogenarians. ANZ J Surg 2005;75:429–35. 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03390.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kirsch M, Guesnier L, LeBesnerais P et al. Cardiac operations in octogenarians: perioperative risk factors for death and impaired autonomy. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;66:60–7. 10.1016/S0003-4975(98)00360-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kolh P, Kerzmann A, Honore C et al. Aortic valve surgery in octogenarians: predictive factors for operative and long-term results. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007;31:600–6. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hewitt TD, Santa PL, Alvarez JM. Cardiac surgery in Australian octogenarians: 1996–2001. ANZ J Surg 2003;73:749–54. 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02754.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Diegeler A, Autschbach R, Falk V et al. Open heart surgery in the octogenarians—a study on long-term survival and quality of life. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1995;43:265–70. 10.1055/s-2007-1013225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ennker J, Dalladaku F, Rosendahl U et al. The stentless freestyle bioprosthesis: impact of age over 80 years on quality of life, perioperative, and mid-term outcome. J Card Surg 2006;21:379–85. 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2006.00249.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kumar P, Zehr KJ, Chang A et al. Quality of life in octogenarians after open heart surgery. Chest 1995;108:919–26. 10.1378/chest.108.4.919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nwaejike N, Breen N, Bonde P et al. Long term results and functional outcomes following cardiac surgery in octogenarians. Aging Male 2009;12:54–7. 10.1080/13685530903033224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chaturvedi RK, Blaise M, Verdon J et al. Cardiac surgery in octogenarians: long-term survival, functional status, living arrangements, and leisure activities. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;89:805–10. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leung Wai Sang S, Chaturvedi RK, Iqbal S et al. Functional quality of life following open valve surgery in high-risk octogenarians. J Card Surg 2012;27:408–14. 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2012.01468.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Caus T, Calon D, Collart F et al. Parsonnet's risk score predicts late survival but not late functional results after aortic valve replacement in octogenarians. J Heart Valve Dis 2002;11:498–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]