Case report

A 26-year-old man presented to the emergency department in a state of collapse. One month prior to the current admission he was seen by a urologist with frank haematuria associated with colicky abdominal pain, increased urinary frequency and dysuria. Although he was initially treated for a urinary tract infection a CT abdomen demonstrated moderate bilateral hydronephrosis. No cause for the hydronephrosis was seen, in particular no calculi. Common bile duct (CBD) was measured at 8 mm. Cystoscopy revealed a diffusely inflamed bladder with marked reduction in capacity (150 cc) but no obstruction at the ureteric orifices. The bladder biopsy showed inflammatory change but no dysplasia or malignancy. No firm diagnosis was reached and the patient was discharged with outpatient follow-up.

For 4 days prior to the current admission the patient had been unwell with increasing flank pain, but had become drowsy and short of breath. On arrival, blood pressure was low at 95/60 mmHg with an associated tachycardia (140 bpm, sinus rhythm) and tachypnoea (60 breaths/min). The Glasgow coma scale was 13/15 with no localizing neurological signs. Initial investigations revealed severe metabolic acidosis (pH 7.2, bicarbonate 6.4 mmol/l, pO2 39.3 kPa, pCO2 2.0 kPa) and acute renal failure (serum potassium 5.4 mmol/l, urea 36.7 mmol/l, creatinine 851 μmol/l). Liver function tests were abnormal with an obstructive pattern (serum bilirubin 58 μmol/l, alkaline phosphatase 294 IU/l, alanine transaminase 106 IU/l, γGT 1045 IU/l). Further history revealed that the patient was a regular user of street ketamine intra-nasally for the past 2 years.

After initial assessment, patient deteriorated quickly with worsening respiratory function requiring intubation. The chest radiograph revealed bilateral basal consolidation consistent with aspiration. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit and vasopressors were required. Continuous haemofiltration (CVVH) and broad-spectrum antibiotics were commenced; blood cultures subsequently grew methicillin-sensitive staphylococcus aureus. A repeat renal ultrasound confirmed hydronephrosis, and bilateral nephrostomies were placed, although the opening pressures were less than expected. Gelatinous debris was aspirated and was present throughout both pelvicalyceal systems, and in the left ureter; this did not have typical appearances of blood clots (Figure 1). Subsequent analysis of this material demonstrated the presence of ketamine metabolites, cannabanoids and lignocaine. A dilated CBD was also observed on ultrasound.

Fig. 1.

Left nephrostogram showing dilated pelvicalyceal systems and proximal ureter. Gelatinous material positive for ketamine metabolites was aspirated from the nephrostomy.

Urine output began to return by Day 2 and bilateral nephrostograms showed free flow of contrast to the bladder with no obstruction. Despite this, CVVH then intermittent dialysis was required until Day 24 when renal function began to recover. Nephrostomies were clamped and then removed, and at discharge serum creatinine was 123 μmol/l. A follow-up ultrasound revealed that the hydronephrosis had completely resolved.

Liver function tests improved spontaneously, and repeat scanning also confirmed resolution of CBD dilatation. The patient required several weeks of rehabilitation and nutritional support following discharge from ITU but had made a full recovery at the point of discharge.

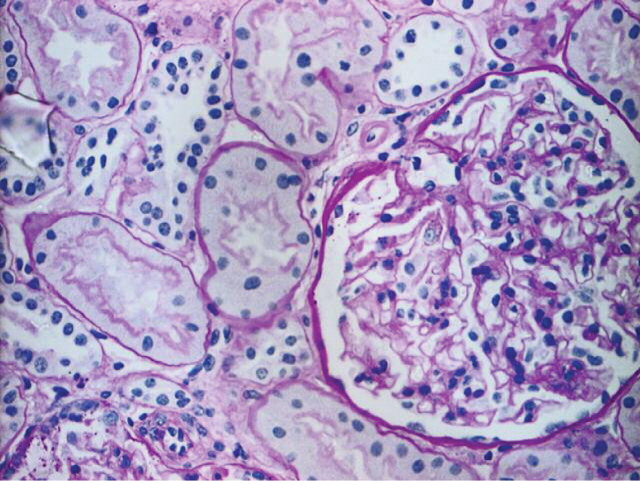

Unfortunately, the patient was readmitted 6 weeks later with right upper quadrant pain and marked derangement of liver function tests (serum bilirubin 7 μmol/l, alkaline phosphatase 1503 IU/l, alanine transaminase 482 IU/l, γGT 561 IU/l). A repeat ultrasound showed that the biliary dilatation had recurred but that the renal tract appeared normal. Serum creatinine had risen again to 294 μmol/l. Urine analysis was positive for ketamine metabolites but negative for other illicit drugs, proving that the patient was abusing this drug again. He was treated for biliary sepsis with improvement of symptoms and subsequently underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). No strictures or stones were seen in the CBD, and a stent was placed. Unfortunately, the patient developed pancreatitis post-procedure. Eight weeks subsequent to this, liver function tests had only partially improved (serum bilirubin 21 μmol/l, alkaline phosphatase 770 IU/l, alanine transaminase 326 IU/l, γGT 1554 IU/l), and after initial improvement, serum creatinine had risen to 309 μmol/l (eGFR 21 ml/min). A further ultrasound showed no evidence of hydronephrosis, so a renal biopsy was performed (Figure 2). The main abnormality was of tubular injury and regeneration with normal vasculature and interstitium. Twenty-two glomeruli were present, all of which were normal apart from one that contained amorphous PAS positive material. Immunofluorescence and electron microscopy were normal. The acute tubular necrosis was felt to be secondary to the sepsis and pancreatitis.

Fig. 2.

Renal biopsy showing a normal glomerulus but with some loss and sloughing of tubular cells consistent with acute tubular necrosis.

Discussion

Ketamine is an anaesthetic agent that is still used extensively in veterinary medicine and in trauma situations. It is increasingly used as a drug of abuse [1] as in lower doses it produces mood elevation, visual hallucinations and feelings of derealization or dissociation [2]. This is the first case report to suggest a mechanism by which ketamine abuse may cause urinary tract abnormalities, and the first in which the patient has required dialysis.

There have been two previous case reports linking ketamine abuse to the development of inflammatory cystitis with low volume bladders [3,4]. In the latter series of 10 patients, 7 had bilateral hydronephrosis and 4 had abnormal serum creatinine values at presentation [4]. Interestingly, all but one of these patients had abnormal liver function tests with an obstructive picture, similar to our patient. No mechanism for the hydronephrosis was identified in this case series.

In our patient, we observed that the gelatinous material formed from ketamine metabolites precipitated in the pelvicalyceal systems and caused obstructive renal failure. The subsequent renal biopsy proved that there was no intrinsic renal pathology. Ketamine is metabolized by the hepatic microsomal system to norketamine and subsequently to hydoxynorketamine, before conjugation with glucuronate and excretion in the urine. However, ketamine does not usually precipitate in the pelvicalyceal systems; the presence of cannabanoid metabolites or the repeated administration with a higher cumulative dose may therefore be crucial. Importantly, the hydronephrosis resolved during the patient's hospital stay when ketamine administration stopped. It is also possible that a similar process occurs in the biliary system to explain the CBD dilatation and abnormal liver function tests, particularly as there was no other cause seen for the CBD dilatation at ERCP. However, ketamine hepatotoxicity would be an alternative explanation [5].

There have been no manufacturers’ reports of ketamine used in a medical setting leading to abnormalities of the renal tract, nor any such findings in animal studies. The mechanism by which street ketamine leads to bladder dysfunction remains obscure although possibilities include direct effects of the drug or its metabolites, an immunological reaction to contaminants used to cut the drug or an interaction between ketamine and other drugs of abuse.

In conclusion, we report for the first time a case of ketamine abuse associated with inflammatory cystitis, reversible hydronephrosis due to precipitation of ketamine metabolites in the ureters and acute renal failure requiring dialysis. Abuse of ketamine should be considered by nephrologists and urologists as a potential cause of unexplained hydronephrosis and bladder inflammation, especially when liver function tests are also abnormal. Some if not all of these effects appear to be reversible upon cessation of the drug.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful for the assistance given by Dr Ivan Robinson in preparing the photographs of the renal biopsy.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.McCambridge J, Winstock A, Hunt N, et al. 5-year trends in use of hallucinogens and other adjunct drugs among UK dance drug users. Eur Addict Res. 2007;13:57–64. doi: 10.1159/000095816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zacny JP, Galinkin JL. Psychotropic drugs used in anesthesia practice: abuse liability and epidemiology of abuse. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:269–288. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199901000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shahani R, Streutker C, Dickson B, et al. Ketamine-associated ulcerative cystitis: a new clinical entity. Urology. 2007;69:810–812. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu PS, Kwok SC, Lam KM, et al. ‘Street ketamine’-associated bladder dysfunction: a report of ten cases. Hong Kong Med J. 2007;13:311–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan WH, Sun WZ, Ueng TH. Induction of rat hepatic cytochrome P-450 by ketamine and its toxicological implications. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2005;68:1581–1597. doi: 10.1080/15287390590967522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]