Sir,

We describe a 30-year-old woman who presented with a progressively enlarging anterior neck mass with pain, local warmth and skin erythema. The patient had been on haemodialysis because of a 3-month history of renal failure due to lupus nephritis. She was also on monthly cyclophosphamide pulse therapy and daily prednisolone (30 mg daily). Her vital signs were as follows: temperature, 37.6°C; blood pressure, 130/80 mmHg; pulse rate, 95–105/min; and respiratory rate, 20/min. Her laboratory results, including thyroid studies, are shown in Table 1. A thyroid scan revealed large defects bilaterally. Initially, subacute thyroiditis was considered the most probable diagnosis, and the daily dose of oral prednisolone was increased to 60 mg. The patient complained of nervousness, irritability, hyperactivity and palpitation, and a β-adrenergic blocker and propylthiouracil were prescribed. When the patient revisited our clinic 3 weeks later, she complained of a progressively enlarging thyroid and respiratory distress. Her chest X-ray revealed tracheal compression and deviation. Because of respiratory failure, she required endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation followed by emergency total thyroidectomy.

Table 1.

Results of the patient’s laboratory tests

| Test | Normal range (unit) | Result |

|---|---|---|

| White blood cell count | 50 000–10 000 (/mm3) | 4440 |

| Neutrophils | 55–75 (%) | 93.4 |

| Lymphocytes | 20–44 (%) | 3.3 |

| Monocytes | 2–8 (%) | 3.0 |

| Haemoglobin | 12–16.0 (g/dL) | 10.0 |

| Haematocrit | 37.0–47.0 (%) | 28.6 |

| Platelet count | 150 000–450 000 (/mm3) | 103 000 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 0–20 (mm/h) | 65 |

| C-reactive protein | 0.1–5.0 (mg/L) | 265.04 |

| Total triiodothyronine (T3) | 0.8–2.0 (ng/mL) | 0.94 |

| Total thyroxine (T4) | 4.5–12.0 (μg/dL) | 16.24 |

| Free T4 | 0.78–1.94 (ng/dL) | 4.05 |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) | 0.3–4.0 (mIU/L) | 0.02 |

| TSH receptor antibody | 0.0–9.0 (U/L) | 0.73 |

| Anti-thyroglobulin antibody | 0.0–70.0 (IU/dL) | 2.47 |

| Anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody | 0.0–100.0 (IU/dL) | 6.67 |

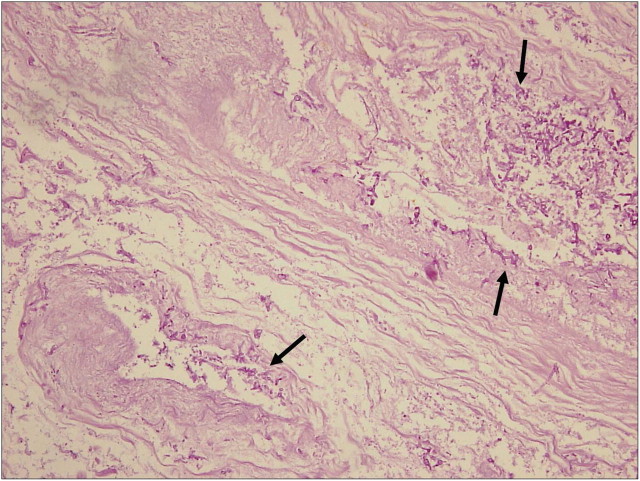

Microscopy of the thyroid revealed infectious thyroiditis with suppurative inflammation, abscess formation, and considerable tissue destruction throughout the gland. Septate hyphae, < 5 μm in thickness, with branching at acute angles were identified. These findings were consistent with a fungal thyroiditis caused by Aspergillus. Blood vessels were invaded by the hyphae of the fungus (Figure 1). A culture of the aspirated fluid showed no growth. The results of repeated tests with an Aspergillus antigen (galactomannan) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) were negative. There was no evidence of aspergillosis in the other organs. Blood and sputum cultures were negative. Intravenous liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg daily) was initiated, and later switched to oral voriconazole (200 mg twice a day for 2 days, and then 100 mg twice a day) on the day of discharge, 2 weeks after the initiation of amphotericin B, and was continued for the following 12 weeks. Because tests showed a decreasing thyroid function, hormone replacement was begun 10 days after surgery.

Fig. 1.

Periodic acid–Schiff stain demonstrates numerous fungal profiles (arrows) in the thyroid stroma with angio-invasion (original magnification, × 200).

Discussion

Isolated fungal infections of the thyroid are uncommon because of its rich vascular and lymphatic supply, well-developed capsule, and high iodine content [1]. Although involvement of the thyroid gland has been detected at autopsy in 9–15% of patients with disseminated fungal disease, there are few reports of isolated infections of the gland without signs of disseminated disease in a living patient [1]. Biopsy, direct microscopy and culture of fine-needle aspirate are still essential for obtaining a diagnosis because systemic antigenaemia (as measured by galactomannan screening) may not develop in patients with localized cases [2].

It is clear that the introduction of the serum Aspergillus galactomannan antigen detection test has made earlier diagnosis possible in high-risk patients. Nonetheless, a major problem with the galactomannan test is that its sensitivity varies greatly, reportedly ranging from 30% to 100%, and its specificity 38% to 98% [3]. Such wide variation in the levels of circulating galactomannan may be attributable to the administration of antifungal drugs, a low frequency of sampling, or a low fungal burden [3,4]. One clinical study suggests that the lesser sensitivity of galactomannan in some patients, especially patients with airway-invasive aspergillosis, might be a result of the minor intravascular fungal burden in these patients [4]. Hence, the cut-off value in the galactomannan assay may need to be set differently for different risk populations [5]. Another possibility is that Aspergillus could be secreting a galactomannan antigen with only one galactofuranose epitope not detected by some ELISA methods. Finally, already formed antibody to Aspergillus might influence the result of the galactomannan test [6].

In conclusion, we report a rare case describing the successful treatment of serum galactomannan-negative isolated Aspergillus thyroiditis in a haemodialysis patient with end-stage renal disease due to lupus nephritis.

Acknowledgments

This case report was approved by the Catholic University of Korea Yeouido St. Mary’s Hospital Institutional Review Board (No. SC10ZZZZ0042).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Goldani LZ, Zavascki AP, Maia AL. Fungal thyroiditis: an overview. Mycopathologia. 2006;161:129–139. doi: 10.1007/s11046-005-0239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guetgemann A, Brandenburg VM, Ketteler M, et al. Unclear fever 7 weeks after renal transplantation in a 56-year-old patient. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2325–2327. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hachem RY, Kontoyiannis DP, Chemaly RF, et al. Utility of galactomannan enzyme immunoassay and (1, 3) beta-D-glucan in diagnosis of invasive fungal infections: low sensitivity for Aspergillus fumigatus infection in hematologic malignancy patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:129–133. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00506-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hidalgo A, Parody R, Martino R, et al. Correlation between high-resolution computed tomography and galactomannan antigenemia in adult hematologic patients at risk for invasive aspergillosis. Eur J Radiol. 2009;71:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guinea J, Jensen J, Peláez T, et al. Value of a single galactomannan determination (Platelia) for the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in non-hematological patients with clinical isolation of Aspergillus spp. Med Mycol. 2008;46:575–579. doi: 10.1080/13693780801978968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saito T, Shime N, Itoh K, et al. Disseminated aspergillosis following resolution of Pneumocystis pneumonia with sustained elevation of beta-glucan in an Intensive Care Unit: a case report. Infection. 2009;37:547–550. doi: 10.1007/s15010-009-8108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]