Abstract

Pre-emptive living donor transplantation should always be promoted as the first-line treatment for kidney failure. Where that is not possible, patients must receive timely information and advice regarding all dialysis options available, including home-based peritoneal dialysis and haemodialysis. Where a dialysis unit enables and actively encourages self-management, patients will tend to select themselves, and if well motivated may overcome significant difficulties to exceed the expectations or predictions of dialysis staff. Patients then become advocates themselves and can provide other patients with the necessary motivation to consider a home treatment, such that they approach staff, rather than vice versa. For staff to be able to talk to patients with confidence requires direct experience of home dialysis, but in units which do not have a full range of home therapies, this may initially be difficult. Visiting patients in their home environment is an essential part of training for both medical and nursing staff. Before a patient is able to begin to engage in discussion about any dialysis therapy, they must have reached a point of acceptance that dialysis is necessary. If they are not at this point, then any attempt at ‘education’ will be largely futile. Once a patient has arrived at the point of choosing a home therapy, the pathway to their first dialysis at home must be as smooth and problem-free as possible.

Keywords: Home haemodialysis, patient choice, peritoneal dialysis, pre-dialysis, patient participation

Introduction

While it is true that not all patients are able to dialyse themselves at home, it is a sad fact that many are never given the chance, despite the fact that ‘Patient Choice’ has never been more discussed as an answer to almost any health care problem. Although studies suggest that renal physicians and nurses regard home dialysis as the best treatment [1], it is in decline in most European countries, yet ‘in-centre’ hospital-based dialysis is the most expensive and most disempowering option available. The practical barriers to home therapy vary from unit to unit but need to be identified and overcome if patients are to benefit from self-management. However, it can be difficult to convince both staff and patients if they have no direct experience or training in this aspect of renal replacement therapy. Winning ‘hearts and minds’ is the first step in this ‘patient pathway’ to (relative) freedom—a step which can be made much easier if staff are familiar with the ‘Stages of Change’ model [2] and have a basic understanding of motivational interviewing.

Patient selection and patient choice

Pre-emptive living donor transplantation should always be promoted as the first-line treatment for kidney failure. However, where that is not possible, patients must receive timely, adequate and unbiased information and advice regarding the complete array of dialysis options available, including home-based peritoneal dialysis (PD) and haemodialysis (HD). Interestingly, a comparison of survival in Canadian patients treated with nocturnal HD or deceased donor kidney transplantation showed no difference between the two treatments, suggesting that this intensive dialysis modality may be a bridge to transplantation, or even a suitable alternative, in the absence of an available living donor [3].

Traditionally around the world, medical and nursing staff, sometimes in conjunction with a social worker, will ‘select’ and approach patients whom they feel may be capable of dialysing at home. However, dialysis choices are generally limited to those modalities a unit currently offers. A clear example of this was evident in the 1990s, when the UK had a large PD population simply because space in hospital HD facilities was limited at that time, and home HD had shrunk to the extent that most UK units no longer had viable programmes. Since that time, in-centre HD facilities in the UK have expanded enormously, such that in some areas supply exceeds demand and the PD population has approximately halved in number. Therefore, many patients currently are not able to choose home HD and patient selection presumably does not generally occur.

Staff are unlikely to be able to advocate a therapy of which they have no experience and are even less likely to advocate one which they perceive to be unavailable. Therefore, health service managers and commissioners also have an enabling role and must embrace the value of self-care by providing the practical resources required. Understandably, a patient may never be adequately informed about home HD or assisted automated peritoneal dialysis if these modalities are not operating in the unit concerned. Many patients will assume that they are not suitable for a home therapy if it is not offered to them, without realizing why it has not been offered. Ideally, every patient should learn about every dialysis modality, accepting that it is probably pointless to discuss PD with a patient who has previously had major abdominal surgery. If this were done, then some patients would inevitably demand the creation of home services where none currently exists, and in one or two UK units, this has already happened.

Experience within our own service suggests that where a dialysis unit enables and actively encourages self-management, patients will tend to select themselves, and if well motivated may overcome significant difficulties, such as needle phobia, housing problems and literacy issues, to exceed the expectations or predictions of even quite experienced dialysis staff. Patients then become advocates themselves and can provide other patients with the necessary motivation to consider a home treatment, such that they approach staff, rather than vice versa.

Staff education

Interestingly, the general consensus among nephrologists in Canada, USA and UK in 2006 was that ∼45% of patients are suitable for a home therapy [4], and if you question the staff in your local HD unit, very few would wish themselves to be dialysed ‘in-centre’ if the need arose. Despite this, the reality is that PD numbers are in decline and home HD is virtually non-existent in many areas. This would suggest that leaving patient ‘selection’ to medical and nursing staff simply does not work and that many capable patients are not finding their way through ‘the system’ to the advantages and relative freedom of home dialysis. Why is this? Clearly, various factors are at play.

There is much in our health care culture that expects care and treatment to be administered by caring and expert professionals, and this expectation is present in the providers of health care as much as it is in the recipients. There are of course individual differences in both staff and patients’ willingness to embrace self-care, but if we assume that cultures and individual preferences are not fixed, then we may find ways to move people along the self-care continuum.

Often, patients contemplating the need for renal replacement therapy are understandably and predictably hoping that dialysis will be ‘done for them’ and will probably shy away from the thought of ‘doing it at home’. Clearly, it is easier and quicker to point them in the direction of in-centre HD than to embark on a difficult and time-consuming discussion around self-care home dialysis and training. To undertake this task, the staff must first be themselves totally convinced that home treatment is in the patient’s best interest—if not, the patient will rapidly detect any hint of uncertainty and further discussion is probably futile. This also means that all members of staff with whom the patient comes into contact must be equally capable of espousing some or all of the benefits of home therapy, from nurse, to doctor, to social worker, to dietician and others. In other words, the unit’s ‘ethos’ must be that home therapy is not only viable but preferable and beneficial for those who are able to pursue it.

For a unit’s staff to be able to talk to patients with confidence requires direct experience of home dialysis, but obviously in many units which do not have a full range of home therapies, this may initially be impossible. Under these circumstances, collaboration with another unit may enable staff to gain the training and experience required to be able to talk with authority and instill confidence in the patient. Visiting patients in their home environment is an essential part of training for both medical and nursing staff.

Patient education

It is known that patients who start dialysis after adequate preparation tend to select a home therapy [5, 6]. This is encouraging, but in some instances, education can default to telling the patient a series of facts, and once the full list of facts is ticked off, the patient is expected to make a choice. Yet, we all know from our own educational experiences that this approach alone is insufficient.

On the face of it, it seems plausible that suitable patients would accept the benefits of a home therapy, once they have been ‘educated’ as to the reasons for the recommendation, and staff may be bemused when they do not do so. This aspect of everyday human behaviour has been most extensively studied in the field of smoking cessation, where it is recognized that someone who has accepted the need to ‘quit’ is much more likely to be successful than someone who has not, despite both being aware of the future health benefits. The Stages of Change model [2] suggests that, for most people, a change in behaviour occurs gradually, with the patient moving from being uninterested, unaware or unwilling to make a change (pre-contemplation), to considering a change (contemplation), to deciding and preparing to make a change (preparation then action). Therefore, before a patient is able to begin to engage in discussion about any dialysis therapy, they must have reached a point of acceptance that dialysis is necessary. If they are not at this point, then any attempt at ‘education’ will be largely futile, especially if it is simply repeated when it may be counter productive and alienating. Even once they have accepted, the need to change a patient may still not be able to engage in the process of change due to real and significant hindrances, such as needle phobia, general anxiety, low mood or fatigue. These issues must be identified and tackled as soon as possible.

5The goal for chronic kidney disease patients at the pre-contemplation stage is to begin to think about the likely 5need for dialysis in the future and where the dialysis should take place. The task for physicians is to empathetically engage the patient in contemplating this change to their life. During this stage, patients may appear argumentative, hopeless or in ‘denial’, and the natural tendency is for physicians to try to ‘convince’ them with more facts, which usually engenders resistance.

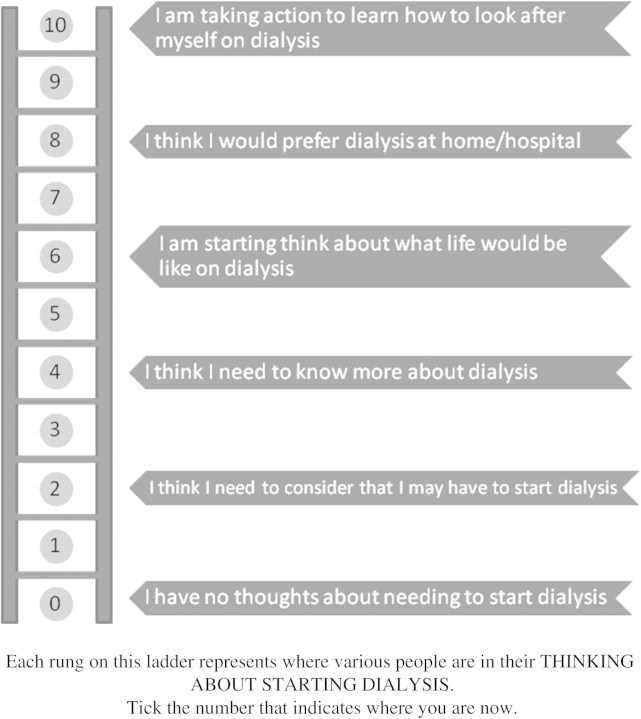

Figure 1 describes the Stages of Change which anyone confronting a life changing event, such as the need to start dialysis, must pass through in order to come to terms with their new situation. Asking the patient to indicate which rung of they ladder they feel they are on can be a helpful first step. Bringing a patient to the stage of taking action in a defined timescale is of great importance since progressive renal disease will not wait, and it is clear that those who start dialysis in an unplanned fashion fare less well. On the other hand, a patient who has reached the action stage may be able to select themselves for either home or hospital therapy as they begin to understand what is, and is not, desirable and possible given their specific circumstances.

Fig. 1.

Thinking about starting dialysis—the ladder of contemplation. Rung 0—pre-contemplation. Rung 1 upwards—contemplation. Rungs 8 and 9—preparation. Rung 10—action.

NICE guidance

The UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) produced guidance on home compared to hospital HD for patients with end-stage renal failure in 2002 [7]. It recommended all patients who are ‘suitable’ for home HD should be offered the choice of having HD in the home or in a renal unit. The definition of ‘suitable’ is expanded in Table 1.

Table 1.

Suggested ‘practical’ characteristics of patients suitable for home HD according to NICE Guidance 2002

| Able and willing to learn to carry out the procedure and to continue with the treatment |

| Have remained in a stable condition while on dialysis |

| Do not have particular problems associated with their kidney disease or do not have other diseases that would make it too difficult or unsafe to carry out HD at home |

| Have blood vessels that are suitable for inserting the catheters (tubes) that carry the blood to and from the dialysis machine |

| Have a carer (or more than one carer) who has decided, after discussing all the issues, to help with the HD (this does not apply to patients who can carry out the HD on their own) |

| Have a home that already has enough space and facilities to setup and use the kidney machine or whose home could be adapted to provide the space and facilities needed |

Although these guidelines are entirely clear and sensible, the Manchester experience is that the definition of ‘suitable’ broadens as the programme expands and staff confidence grows. Enthusiastic and determined patients who might initially have been deemed unsuitable are found to be not only capable but successful home dialysers. Indeed, the current feeling is that very few physical disabilities preclude home treatment if the patient is keen to proceed, and level of enthusiasm is a more reliable guide.

Enabling training

Once a patient has arrived at the point of choosing a home therapy, the pathway to their first dialysis at home must be as smooth and pot-hole free as possible. This requires some resources and infrastructure to be already in place, and if they are not, then all but the most determined patient is likely to be put off. Many patients’ commitment at this stage is fragile and if the path is too rough or steep, or not well signposted, they may understandably decide to turn back. Therefore, from this point on, communication, planning and action must be slick and efficient in order to build the patient’s confidence. The experience and confidence of the staff is crucial so that even if the patient is unsure of the process, they feel fully able to trust the team around them and to know who to turn to for reassurance or answers. It requires staff to engage with patients in conversations about what is important to them and what they value in more general terms (e.g. freedom, independence, safety, quality and quantity of life) and about what the complex hindrances to self-care may be—so that an individualized response to these sorts of questions can move patients along the self-care continuum.

Conclusions

When faced with the spectre of dialysis treatment, most of us would not naturally opt for a home therapy. Traditional methods of patient selection have not prevented a steady decline in home therapies over the past two decades, yet most dialysis unit staff say they would opt for a home therapy for themselves. The Stages of Change model coupled with basic motivational interviewing techniques can enable staff and patients to engage with each other in a more meaningful way such that many patients will be better able to understand the benefits of self-management and treatment at home. Practical infrastructure barriers must also be tackled in order to smooth the pathway to home dialysis.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Ledebo I, Ronco C. The best dialysis therapy? Results from an international survey among nephrology professionals. NDT Plus. 2008;1:403–408. doi: 10.1093/ndtplus/sfn148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psychol. 1992;47:1102–1114. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pauly RP, Gill JS, Rose CL, et al. Survival among nocturnal home haemodialysis patients compared to kidney transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:2915–2919. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nesrallah G, Mendelssohn DC. Modality options for renal replacement therapy: the integrated care concept revisited. Hemodial Int. 2006;10:143–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2006.00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goovaerts T, Jadoul M, Goffin E. Influence of a pre-dialysis education programme (PDEP) on the mode of renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1842–1847. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marron B, Ortiz A, de SP, et al. Impact of end-stage renal disease care in planned dialysis start and type of renal replacement therapy—a Spanish multicentre experience. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(Suppl 2):ii51–ii55. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dillon A. London, UK: National Institute for Clinical Excellence; 2002. Guidance on Home Compared with Hospital Haemodialysis for Patients with End-Stage Renal Failure (TA48) [Google Scholar]