Introduction

Pheochromocytoma is a catecholamine-producing tumor that is often considered in a differential diagnosis of secondary hypertension but rarely diagnosed. The tumor is composed of chromaffin cells responsible for producing catecholamines. The classic triad (headache, palpitations and diaphoresis) is easily recognized by most clinicians, but catecholamine excess can present in a variety of different contexts. We describe the case of a woman who developed catecholamine excess after receiving glucocorticoids for an allergic reaction, which resulted in non-ketotic lactic acidosis, non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema and progressed into cardiogenic shock and acute renal failure. A summary outlining this patient’s presentation, hospital course and management will be discussed; in addition, to relevant literature supporting the findings, management and teaching points.

Case report

A 50-year-old female presented to an outside emergency department with pruritic urticarial rash on her face, which began 24 h prior to seeking medical attention. She had a past medical history for hypertension, hepatitis C and diabetes mellitus. At presentation, she was normotensive on daily doses of amlodipine 5 mg and metoprolol succinate 50 mg without respiratory compromise. She was diagnosed with allergic reaction to an unknown allergen and was empirically treated with hydrocortisone 125 mg intravenously, antihistamines and discharged home. Two hours later, she returns to the emergency department reporting new onset symptoms of chest pressure, heart palpitations, diaphoresis and respiratory distress. She was afebrile, respiratory rate 23 breaths per minute, heart rate 155 bpm and blood pressure 220/100 mmHg. Physical examination was notable for diffuse crackles at bilateral lung fields (See Table 1). Arterial blood gas indicated an anion gap metabolic acidosis with respiratory acidosis and lactic acid of 14.9 mmol/L. Chest X-ray showed pulmonary edema with bilateral lobe infiltrates. Nitroglycerin and enalaprilat was started but she became hypotensive and both medications were discontinued. The cessation of these medications did not improve her hemodynamics, and therefore, intravenous noriepinephrine and vasopressin were initiated. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast evaluating for the presence of pulmonary embolism and aortic dissection showed bilateral lower lobe consolidation, 1.5 cm liver hemangioma and a 3.6-cm left adrenal gland enlargement. Electrocardiogram (EKG) showed sinus tachycardia with nonspecific ST changes. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed global dysfunction with a decreased ejection fraction of 10%. The patient was life flighted to our cardiac intensive care unit for shock due to presumed myocarditis versus sepsis secondary to pneumonia.

Table 1.

Laboratory values on admission and peak values during acute decompensationa

| Test | Admission labs | Peak labs during CCF admission | Normal range |

| WBC | 12.3 × 103/μL (12.3 × 109/L) | 19.4 × 103/μL (19.4 × 109/L) | 4–11 × 103/μL (4–11 × 109/L) |

| Haemoglobin | 13.2 g/dL (132 g/L) | 7.9 g/dL (79 g/L) | 12–16 g/dL (120–160 g/L) |

| Platelets | 248 × 103/μL (248 × 109/L) | 57 × 103/μL (57 × 109/L) | 150–400 × 103/μL (150–400 × 109/L) |

| Sodium | 140 mEq/L (140 mmol/L) | 134 mEq/L (134 mmol/L) | 132–148 mEq/L (132–148 mmol/L) |

| Potassium | 3 mEq/L (3 mmol/L) | 3.3 mEq/L (3.3 mmol/L) | 3.5–5 mEq/L (3.5–5 mmol/L) |

| Chloride | 98 mEq/L (98 mmol/L) | 97 mEq/L (97 mmol/L) | 98–111 mEq/L (98–111 mmol/L) |

| HCO | 12 mEq/L (12 mmol/L) | 16 mEq/L (12 mmol/L) | 23–32 mEq/L (23–32 mmol/L) |

| BUN | 17 mg/dL (6 mmol/L) | 84 mg/dL (30 mmol/L) | 8–25 mg/dL (2.8–9 mmol/L) |

| Creatinine | 1.8 mg/dL (159 μmol/L) | 8.33 mg/dL (736 μmol/L) | 0.7–1.4 mg/dL (62–124 μmol/L) |

| Glucose | 734 mg/dL (40.7 mmol/L) | 162 mg/dL (8.9 mmol/L) | 65–100 mg/dL (3.6–5.5 mmol/L) |

| Anion gap | 30 mEq/L (30 mmol/L) | 21 mEq/L (21 mmol/L) | 0–15 mEq/L (0–15 mmol/L) |

| Albumin | 4 g/dL (40 g/L) | 4 g/dL (40g/L) | 3.5–5 g/dL (35–50 g/L) |

| AST | 50 U/L | 1141 U/L | 7–40 U/L |

| ALT | 67 U/L | 456 U/L | 0–45 U/L |

| Total bilirubin | 0.3 mg/dL (5.1 μmol/L) | 0.7 mg/dL (12 μmol/L) | 0–1.5 mg/dL (0–25.6 μmol/L) |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 107 U/L | 63 U/L | 40–150 U/L |

| pH, arterial | 7.00 | Ventilated | 7.35–7.45 |

| pCO2, arterial | 45 mmHg | Ventilated | 34–46 mmHg |

| pO2, arterial | 66 mmHg | Ventilated | 85–95 mmHg |

| Lactic acid | 134 mg/dL (14.9 mmol/L) | 25 mg/dL (5.8 mmol/L) | 6.3–22.5 mg/dL (0.7–2.5 mmol/L) |

| Serum ketones | Negative | Unavailable | Negative |

| CK | 1637 U/L | 3397 U/L | 30–220 U/L |

| MB | 126 ng/mL (126 μg/L) | 185 ng/mL (185 μg/L) | 0–8.8 ng/mL (0–8.8 μg/L) |

| Troponin T | 0.35 ng/mL (0.35 μg/L) | 7.06 ng/mL (7.06 μg/L) | 0.00-0.1 ng/mL (0–0.1 μg/L) |

CCF, cleveland clinic; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; HCO, bicarbonate

Chart review indicated that she was a nonsmoker, who socially drank alcohol, and never used recreational drugs. Her blood pressure was well controlled using metoprolol succinate 25 mg twice a day and amlodipine 5 mg daily. She had an unremarkable surgical and family history.

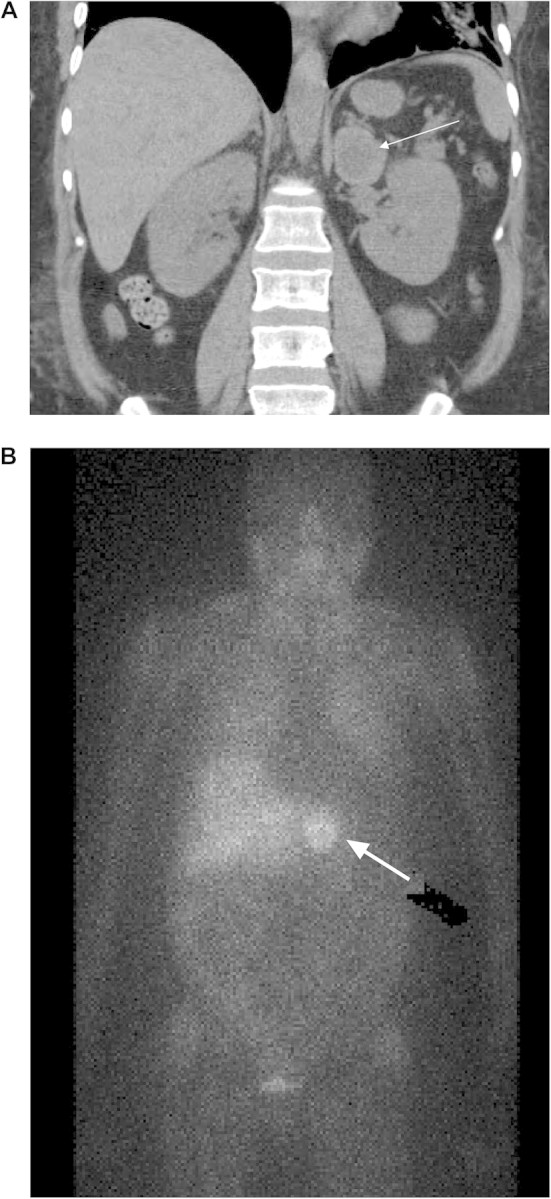

While in the cardiac intensive care unit, the patient remained on vasopressors and required an intra-aortic balloon pump. Workup for hypotension was undertaken and broad spectrum antibiotics were started. All blood and urine cultures showed no growth and cortisol stimulation test was normal (see Table 1). Nephrology was consulted for nonoliguric acute kidney injury (AKI) (baseline creatinine was 1 mg/dL). She was diagnosed with ischemic acute tubular necrosis and contrast-induced nephropathy, which required initiation of renal replacement therapy. After 5 days of supportive care, her hemodynamics improved and her intra-aortic balloon pump and vasopressors were discontinued. Her blood pressure increased to 200/100 mmHg and she required sodium nitropruside drip which was later converted to a four drug oral blood pressure regimen. She was weaned off ventilator support and extubated; her creatinine plateaued at 1.2 mg/dL after dialysis cessasation. The patient was transferred to a regular nursing floor and workup for a functional adrenal mass was initiated. The diagnosis of pheochromocytoma was made on clinical, biochemical and radiographic evidence (See Table 2 and Figure 1).

Table 2.

Pertinent laboratory values for workup of adrenal mass

| Test | Prior to surgery | After adrenalectomy | Normal range |

| Free plasma metanephrine | 1877 pg/mL (9520 pmol/L) | 40 pg/mL (<200 pmol/L) | <40 pg/mL (<200 pmol/L) |

| Free plasma normetanephrine | 4560 pg/mL (24 900 pmol/L) | 137 pg/mL (750 pmol/L) | <165 pg/mL (<900 pmol/L) |

| Plasma epinephrine | 3081 pg/mL (16 822 pmol/L) | <10 pg/mL (<55 pmol/L) | 10–200 pg/mL (55–1092 pmol/L) |

| Plasma noriepinephrine | 8968 pg/mL (53 000 pmol/L) | 401 pg/mL (2300 pmol/L) | 80–520 pg/mL (400–3000 pmol/L) |

| 24-h urine metanephrine | 4462 μg/24 h (22 622 nmol/day) | ND | 52–341 μg/24 h (263–1728 nmol/day) |

| 24-h urine normetanephrine | 2912 μg/24 h (15 900 nmol/day | ND | 88–444 μg/24 h (480–2424 nmol/day) |

| 24-h total urine metanephrine | 7374 μg/24 h (38 787 nmol/day) | ND | 140–785 μg/24 h (736–4129 nmol/day) |

Fig. 1.

(A) Abdominal CT scan showing a cross sectional view of a 3.6 cm left adrenal mass. (B) MIBG scan (123-I- metaiodobenzylguanidine) showing a large focal uptake on the left upper abdomen measuring 3.5 cm.

For blood pressure control before surgery, doxazosin (uptitrated at 2 mg increments every third day up to a maximum of 10 mg/day) was added to daily doses of metoprolol succinate (50 mg) and amlodipine (10 mg). She successfully underwent left adrenalectomy without complications. Final pathology reported a well encapsulated minimally fibroadipose tissue measuring 4.5 × 4.1 × 3.2 cm located in the medulla of the adrenal gland consistent with pheochromocytoma. The patient was screened for multiple endocrine neoplasm 2 (MEN2a and b), which was negative. She continued to improve postoperatively and was discharged home. At 6 months follow-up, she was clinically doing well with good blood pressure control on metoprolol 25 mg twice a day and amlodipine 5 mg daily.

Discussion

Our patient experienced an acute hypertensive crisis followed by cardiovascular collapse precipitated by the administration of intravenous glucocorticoids for an allergic reaction. Glucocorticoids increase circulating catecholamines through a variety of mechanisms, which include inhibition of catechol O-methyl transferase[1], induction of pheylethanolamine-N-methyltrasnferase[2] and increase tyrosine hydroxylase kinase activation[3] (See Figure 2). The patient returned to the emeregency department, in a hypertensive crisis requiring intravenous blood pressure medications, pulmonary edema and type A non-ketotic lactic acidosis which is a presenting feature of pheochromoctyoma. Our patient had a mixed tumor which produced both epinephrine and norepinephrine, both which are equally responsible for an elevated systolic blood pressure. The production of lactic acid is the direct result of the norepinephrine causing peripheral vasoconstriction, in the presence of epinephrine which increases the metabolic needs of the target tissue. The discordance between oxygen supply and demand results in tissue anoxia, glycogenolyis and pyruvate metabolism leading to the generation of lactic acid [4]. Glycogenolyis and increased resistance to insulin from catecholamine excess also explains her glucose level of 734 mg/dL.

Fig. 2.

Catecholamine metabolism

Our patient developed a non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema prior to her cardiovascular collapse which required intubation. Pheochromocytoma has been shown to cause cardiogenic and non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema in case reports [5]. Non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema is due to catecholamine excess leading to increased total peripheral resistance and pulmonary venous hypertension, which leads to increased pulmonary capillary wedge pressure [6]. Cardiogenic pulmonary edema is seen with a depressed left ventricular dysfunction which are patient eventually developed.

Cardiomyopathies which include dilated or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [7], myocarditis [8] and takotsubo [9] (apical ballooning of the left ventricle) have all been described in pheochromocytoma which often are reversible with treatment. Our patient initially presented to the emergency department in a hypertensive crisis, and later developed global cardiac dysfunction from myocarditis. Catecholamine excess causes cardiotoxicity through a variety of mechanisms which include increase in cell membrane permeability, increase in oxygen consumption, free radical formation and consumption of intracellular adenosine triphosphate resulting in ischemia and myocyte necrosis [10]. Interesting, our patient was diagnosed with myocardial infarction at another facility in the setting of elevated troponins prior to this admission. Unfortunately, no creatine kinase EKG, creatine kinase mb or EKG was available, but on cardiac catheterization, she had normal coronary arteries and an ejection fraction of 60%. High circulating levels of norepinephrine and epinephrine have been implicated in myocardial ischemia from acute coronary artery vasospasm [10, 11].

Most AKI in the setting of catastrophic pheochromocytoma crisis resulting in global cardiac dysfunction is due to ischemic acute tubular necrosis. There are case reports of AKI from pheochromocytoma causing hemolytic anaemia and rhabdomylysis [12]. Our patient presented with an elevated creatinine 1.8 mg/dL (baseline serum creatinine 2 mg/dL) prior to the potential of developing AKI from contrast-induced nephropathy and ischemic acute tubular necrosis. After her potential renal insults, she had a urinalysis with microscopy which confirmed ischemic acute tubular necrosis. Excessive adrenergic stimulation of the alpha-receptors on the basolateral surface of the proximal tubules has been shown to cause preferential afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction and a decrease in renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate [13].

The incidence of pheochromocytoma in the general population is 0.8% per 100 000 people and is often not diagnosed or managed by many internists, endocrinologist and nephrologists [14]. We describe a case of a woman who develops an adrenergic crisis precipitated by glucocorticoid administration for an allergic reaction. Excess catecholamine release caused hypertension, type A non-ketotic lactic acidosis and non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema. After initiation of intravenous antihypertensive medications and suspected catecholamine depletion, the patient developed cardiogenic shock from myocarditis. Ischemic acute tubular necrosis was diagnosed after the above events occurred, however, it is postulated that she could have experience a decreased glomerular filtration rate from intense vasoconstriction of afferent arterioles due to excessive norepinephrine release. Fortunately, the patient made a full recovery but there are several teaching points that can be highlighted from this case report.

(1)Hyperadrenergic states can be precipitated by glucocorticoid administration, anesthesia, surgery, certain foods containing tyrosine and monoamine oxidase inhibitor. Patients who develop paroxysmal hypertension or experience a cardiovascular event after exposure to the above should be assessed for pheochromocytoma.

(2)Headache, diaphoresis and palpitations are not always present and other manifestations need to be considered. A diagnosis of pheochromocytoma should be considered in patients presenting with type A non-ketotic lactic acidosis in the setting of a hypertensive crisis.

(3)Catecholamine excess has been shown to cause myocarditis, takotsubo, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy from direct cardiotoxicity leading to cardiogenic shock. Non-cardiogenic and cardiogenic pulmonary edema are caused by pheochromocytoma.

(4)Doxazosin, a specific antagonist of post synaptic α1 receptor, combined with a calcium channel antagonist is efficacious and safe in the preoperative preparation of patients with pheochromocytoma.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Lindley SE, She X, Schatzberg AF. Monoamine oxidase and catechol-o-methyltransferase enzyme activity and gene expression in response to sustained glucocorticoids. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;8:785–790. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharara-Chami RI, Joachim M, Pacak K, et al. Glucocorticoid treatment—effect on adrenal medullary catecholamine production. Shock. 2009;34:40–43. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181af0633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodman R, Edgar H, Thoenen H, et al. Glucocorticoid induction of tyrosine hydroxylase in a continuous cell line of rat pheochromocytoma. Metabolism. 2002;51:11–14. doi: 10.1083/jcb.78.1.r1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madias NE, Goorno WE, Herson S. Severe lactic acidosis as a presenting feature of pheochromocytoma. Am J Kidney Dis. 1987;3:250–253. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(87)80182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeshita T, Shima H, Oishi S, et al. Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema as the first manifestation of pheochromocytoma: a case report. Radiat Med. 2005;2:133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rassler B. The role of catecholamines in formation and resolution of pulmonary edema. Cardiovasc Haematol Disord Drug Targets. 2007;7:27–53. doi: 10.2174/187152907780059038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jategaonkar SR, Butz T, Burchert W, et al. Echocardiac features simulating hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy in a patient with pheochromocytoma. Clin Res Cardiol. 2009;98:195–198. doi: 10.1007/s00392-009-0748-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu XM, Chen JJ, Wu CK, et al. Pheochromocytoma presenting as acute myocarditis with cardiogenic shock in two cases. Intern Med. 2008;47:2151–2155. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossi AP, Bing-You RG, Thomas LR. Recurrent tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy associated with pheochromocytoma: a case report. Endocr Pract. 2009;2:1–11. doi: 10.4158/EP09005.CRR1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Behonick GS, Novak MJ, Nealley EW, et al. Toxicology update: the cardiotoxicity of the oxidative stress metabolites of catecholamines (aminochromes) J Appl Toxicol. 2001;21:15–22. doi: 10.1002/jat.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boulmier D, Bazin P. Myocardial pseudo-infarction: “stress”-associated catecholamine-induced acute cardiomyopathy or coronary spasm? Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris) 2000;49:449–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anaforoglu I, Ertorer ME, Haydardedeoglu FE, et al. Rhabdomyolysis and acute myoglobinuric renal failure in a patient with bilateral pheochromocytoma following open pyelolithotomy. South Med J. 2008;101:354–355. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318167ab4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiBona G. Neural control of the kidney. Past, present and future. Hypertension. 2003;43:147–150. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000047205.52509.8A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golden S, Robinson K, Saldanha I, et al. Prevalence and incidence of endocrine and metabolic disorders in the United States: a comprehensive review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1853–1879. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]