Abstract

A National Library of Medicine information access grant allowed for a collaborative project to provide computer resources in fourteen clinical practice sites that enabled health care professionals to access medical information via PubMed and the Internet. Health care professionals were taught how to access quality, cost-effective information that was user friendly and would result in improved patient care. Selected sites were located in medically underserved areas and received a computer, a printer, and, during year one, a fax machine. Participants were provided dial-up Internet service or were connected to the affiliated hospital's network. Clinicians were trained in how to search PubMed as a tool for practicing evidence-based medicine and to support clinical decision making. Health care providers were also taught how to find patient-education materials and continuing education programs and how to network with other professionals. Prior to the training, participants completed a questionnaire to assess their computer skills and familiarity with searching the Internet, MEDLINE, and other health-related databases. Responses indicated favorable changes in information-seeking behavior, including an increased frequency in conducting MEDLINE searches and Internet searches for work-related information.

BACKGROUND

The distribution of health professionals in the United States today plays a critical role in the myriad issues surrounding access to quality health care. In New York State, more than 150 communities have been designated as health professional shortage areas (HPSAs). In response, the New York State Area Health Education Center (AHEC) Program was initiated in 1998 with a mission to

enhance the quality of and access to health care, improve health care outcomes and address health workforce needs of medically underserved communities and populations by establishing partnerships between the institutions that train health professionals and the communities that need them most. [1]

Based at the University at Buffalo's Department of Family Medicine, New York AHEC's strategies included placement opportunities for health sciences students in underserved communities, provision of continuing education and professional support to providers in these communities, and encouragement of local youth to pursue careers in health care. The New York AHEC built upon the previous efforts of the Primary Care Resource Center, which created community-based clinical teaching sites in HPSAs for medical students and residents [2].

Similarly, the Hospital Library Services Program (HLSP) was formed in 1982 by the New York State Legislature to provide medical information services to acute care hospitals throughout the six western New York counties. Its services are offered through two primary programs: the Grant Hospital Program, which provides grant dollars to help defray the costs of library materials and equipment, and the Circuit Hospital Program, which provides onsite medical librarian visits as well as grant dollars. The circuit librarians facilitate interlibrary loans and provide bibliographic instruction, literature searches, collection development, and reference services. The HLSP is administered by the Western New York Library Resources Council and is funded in part by the New York State Department of Education, Division of Library Development, and by hospital participation fees.

Recognizing a synergistic relationship, AHEC and HLSP partnered to secure a National Library of Medicine (NLM) Information Access Grant “Facilitating Access to the Computerized Information Resources of the National Library of Medicine for Health Care Professionals in Underserved Areas of Western New York” (1 G07 LM06847-01). Participants in the project were taught how to search MEDLINE, how to access quality information resources on the Internet, and how to request materials through their HLSP circuit librarian. The project's goals and objectives were to:

ensure that health care professionals in clinical practice sites affiliated with AHEC and HLSP had access to the information they needed to provide quality care to their patients

provide computer resources onsite that enabled health care practitioners to access quality, user-friendly, cost-effective medical information via PubMed and the Internet

develop a cadre of well-trained health care professionals who could serve as mentors and role models to students and residents

create a virtual, community-academic clinical practice network with a mission to support excellence in patient care and multidisciplinary practice

LITERATURE REVIEW

How primary care practitioners working in underserved rural and urban areas accessed the information they needed to deliver quality health care to patients has been of concern to academic health sciences centers and federal, state, and local government agencies for more than fifteen years. Dorsch's review, published in 2000, focused on the lack of access to health information confronted by rural health care professionals [3]. Many of the same issues also were applicable to health care providers practicing in urban underserved communities. With support from NLM, many efforts have been made to redress these discrepancies. Under the umbrella of outreach projects funded by NLM through the National Network of Libraries of Medicine (NN/LM), funds were dispersed across the United States. Pifalo, in her introduction to the symposium “Perspective on Library Outreach to Health Professionals and Citizens in Rural Communities,” provided an excellent overview of the goals and objectives that inspired NN/LM to support these outreach efforts [4].

McDuffee, writing in the same symposium, described the model library services program developed and maintained throughout North Carolina by the AHEC Library and Information Services Network based at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Not only did North Carolina fund statewide library services through its AHEC program, but also, in more recent years, it supported the creation of a statewide digital library network for rural practitioners. The work of McDuffee and colleagues strongly influenced the conceptual framework of the project reported here [5]. While North Carolina's network was under development before the Internet had reached its full potential, the New York AHEC information access project benefited significantly from having ease of access to the Internet, even in rural settings.

In a 1999 publication, Westberg and Miller provided an extensive review of the information needs of primary care providers in all work settings and described their efforts to empower primary care physicians by providing a three-tiered system for accessing health information. The first level used a “Web-based secure interface” to reach digital information resources housed at the health sciences library. Levels two and three provided a sophisticated triage system for evaluating and responding to a practitioner's more complex information requests. An important component of the project was the availability of a human gatekeeper at level three [6].

The information-seeking behavior of primary care practitioners has been widely studied and reported in the literature; however, evaluations of these efforts have been more limited. Richwine and McGowan offered interesting outcome data. They employed similar strategies as the present study to ascertain prior experience in using medical information systems, and they found that, although the intent of their study “was to provide information at the point of clinical decision making, the majority of survey respondents indicated that they used the system from home” [7]. That finding was not duplicated in this study.

The AHEC program at the Medical College of Ohio at Toledo developed MedReach, an outreach effort for health care professionals practicing in underserved areas of northwestern Ohio. MedReach enabled providers to search medical databases and textbooks via the Internet. Users of MedReach received personalized help with the search process by telephoning or emailing the outreach librarian. In addition, the Medical College of Ohio library offered formal training sessions for MedReach users [8].

METHODOLOGY

The project initially involved ten clinical practice sites located in HPSAs that were affiliated with HLSP member hospitals and served as training venues for New York AHEC students. By enhancing the sites with computers and Internet access, it was hoped students would be more inclined to rotate in HPSAs, furthering the New York AHEC mission. Additionally, as HLSP affiliates, clinicians were able to request journal articles generated from their PubMed searches through the circuit librarian. Sites were located throughout five predominantly rural counties in western New York. According to the US Census Bureau, Census 2000, an average of 12% of the population in these counties lived below the poverty level [9]. The composition of the sites varied greatly. The number of staff per site decreased as the sites became more rural and more remote from Buffalo. The sole urban clinical practice site was located in inner city Buffalo and had a staff of 20. The urban site was well staffed when compared to the site in Amish country (located approximately 40 miles south of Buffalo) that consisted of 1 physician, 1 nurse, and 1 receptionist. On average there were 3 nurses, 1 mid-level provider, and 2 physicians per site.

During year one, the grant provided half of the salary of the project coordinator as well as a computer, Internet access for one year, a printer, and a fax machine at each site. The computers were installed by the project coordinator. The fax machine was intended to facilitate interlibrary loan requests that could be sent to the HLSP circuit librarian. Dial-up Internet service was budgeted for all sites; however, those sites that were affiliated with a networked hospital were placed on their networks and benefited from high-speed connections. The information access grant was intended to be a one-year effort; however, delays occurred due to the closing of several planned sites. As a result, the project team needed to identify alternate sites. A one-year, no-cost extension was received, and, with unspent funds, four additional sites were enlisted to participate. Due to budgetary restraints, the four sites added during year two of the project did not receive fax machines.

All clinical staff—including physicians, mid-level providers (nurse practioners and physician assistants), and nurses—participated in the project. Demographically, a majority were female (64%) and full-time employees (73%). Seventy-two percent of the participants were between the ages of 35 and 54. Sixty-one percent characterized themselves as regular computer users, and 59% rated themselves as “good” or “very good or excellent” in regard to their confidence in using a computer.

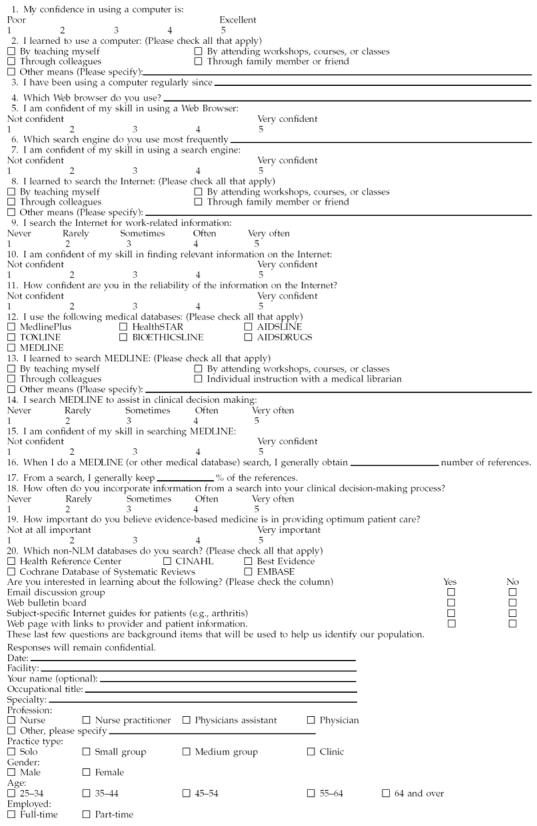

A comprehensive self-assessment questionnaire (Appendix A) that examined prior computer use including bibliographic databases searched as well as the individual's confidence level in using a computer was developed by a research analyst in the Department of Family Medicine. The perceived importance of evidence-based medicine (EBM) was measured as well as how often information seeking was integrated into clinical decision making. The objective was to determine the short- and long-term effectiveness of providing access to, and individualized training with, PubMed and the Internet in clinical practice settings. The self-assessment questionnaire was administered pre-intervention, immediate post-intervention, and three months post-intervention. Results of the pre-intervention questionnaire enabled the project team to understand participants' knowledgebase prior to the intervention, while the post-intervention questionnaires measured learning and use of the systems over time. Pre-intervention questionnaires were sent to participants and mailed back or were distributed at the time of installation. The immediate post-intervention questionnaire was handed out at the training, but not all were completed at that time. The three months post-intervention questionnaire was mailed and returned by mail to the project coordinator. A training evaluation questionnaire (Appendix B) was given to assess the effectiveness of the training session.

The results of the pre-intervention questionnaire demonstrated substantial variance in the knowledge, skills, and abilities of participants. Thus, a multifaceted training program tailored to accommodate the varying skill sets of participants was held at each site. The training program focused on using PubMed as a tool for practicing EBM for both physicians and mid-level providers. A review of EBM and PubMed search strategies for keywords, authors and journals was included, as well as more advanced features such as the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) browser and the clinical queries filter. Nursing staff also were trained to use MedlinePlus to locate patient-education materials. The nurses were taught searching by keyword, browsing by system, and using features such as the directory and additional links. The sessions also discussed how to assess the authority of a Website for provider and patient information. The important role of the HLSP circuit librarian was emphasized, including how to request journal articles identified through PubMed searches. Participants were given a PubMed “cheat sheet” outlining basic search strategies. The cheat sheet ensured that participants had ready access to follow-up training materials after the intervention was completed.

The project coordinator was always available via telephone or email. In addition, site visits could be arranged to assist with hardware problems or to provide additional instruction. Because many of the participating health care professionals practiced in remote locations, it became apparent that the Internet could serve as a tool to decrease the sense of isolation many rural providers experienced. The training program was amended to ensure that participants maximized the benefits of Internet access, including access to continuing education resources and email discussion groups to communicate with colleagues.

RESULTS

Data collection proved to be the most challenging aspect of the project. Approximately seventy clinicians participated at all of the sites. Pre-intervention responses numbered fifty-six, while post-intervention responses decreased to thirty-three. The project team attributed this to a lack of time and motivation to complete the forms as well as the lengthy nature of the forms. As stated previously, many participants did not complete the immediate post-intervention assessment on the day of the training due to time constraints, which may also have affected the response rate to the third questionnaire.

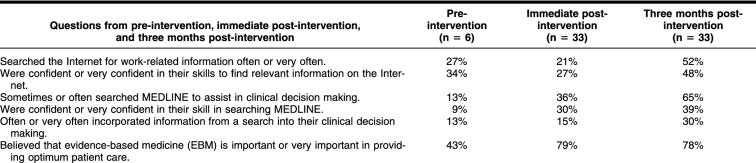

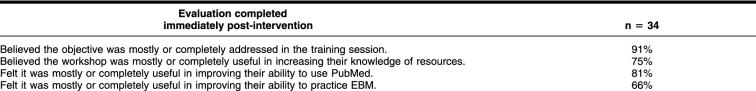

Respondents indicated favorable changes in information-seeking behavior as a result of the training. The number of respondents who searched the Internet for work-related information “often” or “very often” increased 25%. While those who searched MEDLINE “sometimes” or “often” increased by 52%. Only 9% rated themselves as “confident” or “very confident” in searching MEDLINE prior to the intervention. When the three months post-intervention questionnaire was administered, the confidence level of respondents increased to 39%. By the conclusion of the project, the perceived importance of EBM in providing quality patient care increased by 35%. The level of perceived confidence in finding relevant information on the Internet decreased slightly between the pre-intervention and immediate post-intervention questionnaire. The investigators believed this response was the result of the emphasis placed on instructing participants how to distinguish between reliable and untrustworthy Internet sites. In regard to the training session itself, a vast majority (91%) felt the training “mostly” or “completely” addressed the stated learning objectives of the program, while 81% felt it was “mostly” or “completely” useful in improving their ability to use PubMed. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the results obtained from the questionnaires.

Table 1 Self-assessment questionnaire results

Table 2 Training evaluation results

DISCUSSION

The project met its goals of ensuring that site-based health care professionals had access to the information they needed to provide quality care to their patients and were appropriately trained in how to access quality, reliable health care information. The project had the most significant impact on the sites that previously lacked Internet access. For those sites that were already connected to the Internet, the project served to reinforce search skills and further integrate EBM into the individuals' clinical practice.

One of the major obstacles confronted by the project team was getting sites connected to the Internet. Insufficient telephone lines, lack of funds to pay for an additional telephone line (which was considered an in-kind contribution to the project), or lack of support from the hospitals' information systems departments caused some of the delays. Although half of the sites already had access to the Internet, the computers were typically located in physicians' offices where other clinical staff did not have easy access to them. Overall, sites that received strong support from the hospitals' information systems departments were wired in a more efficient and timely manner.

The location of the computer in the practice was a key factor in ensuring that it was well used for clinical decision making. The process of selecting a site for the computer proved to be challenging at times. When possible the computer was placed in the nurses' station due to its centralized location. Out of the fourteen sites, eight computers were placed in the doctor's office, four were placed at the nurses' stations, and two were placed in other common areas. Despite the intention that the computer be dedicated to information access and searching, the computer was often used for other purposes, an indication perhaps of how great the need for technology was at the sites. For example, when the computer was placed in the reception area, it was sometimes used for billing.

Many of the physicians lacked the time needed to participate in the training program. Physicians frequently arrived late for their training sessions or could devote only a fraction of the time planned for instruction. Two of the original sites decided they were not interested in participating in the project. One site was unwilling to allocate any training time for the clinicians, and the other site was unwilling to install an additional telephone line to establish Internet service. Despite numerous attempts to contact these sites and explain the value of participating in the training, the project team was unable to persuade the sites to follow the protocol. As a result, both sites were eliminated from the program.

An unexpected result of the project was the enthusiasm of the nursing staff in integrating information-seeking behavior into their daily practice. Despite the fact that this project was often the nurses' first exposure to formal bibliographic training or computer training in general, the nurses tended to use the computer more often than the physicians and mid-level providers. The ease of integrating information-seeking behavior into the nurses' practice might be attributed to a variety of factors. The nurses had more discrete clinical questions, such as, “Is there an updated height and weight chart available from the Centers for Disease Control?” Additionally, nurses might have had more time available to use the computer than physicians. The utilization of information by nursing staff in outpatient practices warrants further study.

The sites were distinct microcosms of clinical practice, and each site reacted differently to the project. In general, the training was more positively received at the more remote sites, because the project gave both nurses and physicians a sense of empowerment in finding quality health care information for both their patients and themselves and in being connected to other health care providers. As one participant stated, “This is vital for us remote rural MDs. I may spend 4 weeks at a time without a face to face conversation with another doctor, so this type of informal communication makes a big difference.” An ideal expansion of the project would be to implement telemedicine services at the remote clinical practice sites. Many participants expressed the need for access to telemedicine equipment to decrease the number of referrals that they were required to make to specialists. For example, a physician whose patient population was predominantly Amish was unable to refer patients to specialists due to transportation and financial constraints.

Several additional positive results of the project were also noted, including an improved awareness of services furnished by hospital libraries as evidenced by an increase in interlibrary loans and requests for mediated literature searches. Overall the project was successful in educating clinicians about the importance of information-seeking behavior and incorporating EBM into clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Thomas C. Rosenthal, chair of the University at Buffalo Department of Family Medicine, for his support of the project. The authors also acknowledge Robin Graham and B. Lauren Young for assistance in designing the questionnaires and Andrew Danzo for his editorial assistance.

APPENDIX A

Self-assessment questionnaire, New York Area Health Education Center Program, Hospital Library Services Program, National Library of Medicine Information Access Project

APPENDIX B

Training evaluation, New York Area Health Education Center Program, Hospital Library Services Program, Information Access Project

Objective: Participants will receive an overview of PubMed and other Internet resources for obtaining up-to-date clinical information to support patient care.

-

How adequately was this objective addressed in the training session?

Not at all In part Mostly completely

-

How useful overall was the workshop in increasing your knowledge of computerized medical information resources?

Not at all In part Mostly completely

-

How useful was this workshop in improving your ability to use:

Internet:

Not at all In part Mostly completely

PubMed:

Not at all In part Mostly completely

Evidence-based medicine:

Not at all In part Mostly completely

Overall, what is least clear to you about accessing information on the Internet to support patient care? (Please write response) _______________________________________

Footnotes

* This program was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant no. 1 G07 LM06847-01 from the National Library of Medicine.

† Based on a presentation at MLA '02, the 102nd Annual Meeting of the Medical Library Association; Dallas, Texas; May 2002.

Contributor Information

Jennifer A. Byrnes, Email: jennifer_byrnes@urmc.rochester.edu.

Tracy A. Kulick, Email: takulick@wnylrc.org.

Diane G. Schwartz, Email: dschwartz@Kaleidahealth.org.

REFERENCES

- New York State Area Health Education Center System. About us. [Web document]. Buffalo, NY: The System. [cited 1 Apr 2004]. <http://www.ahec.buffalo.edu/about.htm>. [Google Scholar]

- James PA, Schwartz DG, Rosenthal TC, and Feather JN. Community academic practices: a model for ambulatory-based training at the State University of New York at Buffalo. Manual on Community Based Teaching. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians, 1997:186–96. [Google Scholar]

- Dorsch JL. Information needs of rural health professionals: a review of the literature. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000 Oct; 88(4):346–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pifalo V. The evolution of rural outreach from Package Library to Grateful Med: introduction to the symposium. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000 Oct; 88(4):339–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDuffee DC. AHEC library services: from circuit rider to virtual librarian. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000 Oct; 88(4):362–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westberg EE, Miller RA. The basis for using the Internet to support the information needs of primary care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1999 Jan–Feb; 6(1):6–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richwine MP, McGowan JJ. A rural virtual health sciences library project: research findings with implications for next generation library services. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2001 Jan; 89(1):37–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner V, Hartmann J, and Ronau T. MedReach: building an Area Health Education Center medical information outreach system for northwest Ohio. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002 Jul; 90(3):317–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. [Web document]. Washington, DC: The Bureau. [cite 23 Jun 2003]. <http://www.census.gov>. [Google Scholar]