Abstract

Objectives: For librarians developing a credit course for medical students, the process often involves trial and error. This project identified issues surrounding the administration of a credit course, so that librarians nationally can rely more upon shared knowledge of common practices and less upon trial and error.

Methods: A questionnaire was sent to the education services librarian at each medical school listed in the 2000 AAMC Data Book. A second questionnaire was sent to those librarians who did not return the first one.

Results: Of the 125 librarians surveyed, 82 returned the questionnaire. Of those 82, only 11 offered a credit course for medical students, though 19 more were in the process of developing one. Data were gathered on the following aspects of course administration: credit course offerings, course listing, information learned to administer the course, costs associated with the course, relationships with other departments on campus, preparation for teaching and grading, and evaluation of the course.

Conclusions: Because of small number of respondents offering a credit course and institutional variations, making generalizations about issues surrounding the administration of a credit course is difficult. The article closes with a list of recommendations for librarians planning to develop a course.

INTRODUCTION

The emphasis on the need for medical professionals to maintain professional competence through lifelong learning has provided opportunities for health sciences librarians to work with students and faculty in new ways. While information management education (IME) has long been an important component of information services in academic health sciences libraries, its role has been highlighted by institutional information management exit objectives and suggested by a report from the Association of American Medical Colleges' (AAMC's) Medical School Objectives Project [1]. Existing IME programs include skills such as literature searching, cited reference searching, use of presentation and bibliographic management software, and use of evidence-based practice; one group of the AAMC's objectives, “Role of Life-Long Learner,” fits closely with these existing programs. For example, one objective includes demonstrating knowledge of information sources such as MEDLINE, reference sources, textbooks, and medical Internet sites to support lifelong learning. Another addressed online search techniques such as using controlled vocabulary and Boolean operators when searching online resources. Although it has been left up to each medical school to determine whether or not these objectives would be adopted and to what extent they were adopted, librarians have been able to use this document to their advantage, using relevant objectives when refining existing IME programs and when developing new ones.

Information management education for medical students takes a variety of forms, often depending upon the political climate of the institution. Traditional forms of IME take place in brief, often single, sessions as a part of orientation or a course such as medical decision making, problem-based learning, or evidence-based practice. It may also take place outside of existing courses, as with training sessions that are open to the campus. These types of sessions assume that students can quickly absorb knowledge about information sources and the skills needed to use these sources effectively, with little or no need for follow-up. These “one-shot” sessions, however, are not effective for all students. One way to improve IME and to cover more of the AAMC's informatics objectives in more depth is by offering a credit course, where students and librarians can meet over an extended period (such as a semester or block). The primary benefit offered by credit courses is the “time available for instruction. [They allow] time for a structured and comprehensive approach to learning. Students have time to develop search strategies, to explore alternative approaches, and to practice information-seeking behavior under controlled circumstances” [2].

In 1997, the Raymon H. Mulford Library at the Medical College of Ohio (MCO) first offered a credit course as an elective for fourth-year medical students. Planning for this elective began the previous year with meetings of the assistant director for library services, the head of information services, and the reference/ education librarian. While a number of reports have been published regarding the content of credit courses in information management in medical schools [3–8], no studies were found focusing extensively on the administration of these courses, examining academic medical libraries as a group. For many librarians, setting and teaching the curriculum is only half the battle. The other half is dealing with the complexities of the academic environment. At MCO, the course coordinator struggled to learn to juggle the myriad forms from the registrar, to revise and re-revise the syllabus to help the students produce the desired projects, and to grade projects quickly and fairly. The first year that MCO offered the elective is still referred to as “the big learning experience.”

To improve this process for other librarians, this research project gathered information on issues surrounding the administration of credit courses in information management in US medical schools. Its goal was to assist librarians who are developing or planning to develop a credit course by informing them about the problems that they may face, so that they are better prepared to address them. The study answered the research question: What administrative issues have librarians faced when teaching credit courses in US medical schools? Secondary research questions addressed the issues of how librarians learned to administer a credit course and what could have been done to facilitate the learning process.

METHOD

A questionnaire was developed and mailed to librarians in charge of information management education at all 125 medical schools in the United States, as listed in the 2000 AAMC Data Book [9], which provided the most comprehensive and up-to-date listing of accredited medical schools in the United States. Because there are relatively few medical schools in the United States, compared to the total number of institutions of higher education, and because many of these schools do not offer credit courses in information management, all libraries were surveyed to assure adequate coverage. Academic medical center libraries may also support programs in nursing, dentistry, and allied health fields, as well as graduate programs in the basic sciences (such as biochemistry and anatomy). To minimize the complexity of variations in administrative requirements based on type of program, this survey only gathered information about credit courses offered in medical schools for medical students.

The questionnaire was a six-page document with questions falling into eight categories (Appendix). The first category, “Credit Course Offerings,” gathered information about whether a credit course was offered or not, whether the course was required or elective, how often it was offered, and how long the course ran. The second category, “Course and the Overall Scheme of Courses at the Institution,” looked at where credit courses fall in the curriculum. It was expected that courses have been placed in a variety of departments, so this section also assessed the benefits and drawbacks of the placements as perceived by the librarians. The third component, “Learning to Administer a Credit Course,” gathered information on how librarians learn to administer a course for credit in a medical school. Component four, “Costs Associated with the Course,” looked at time and financial costs associated with offering a credit course. “Relationships with Other Departments” gathered information about which other departments on campus impose requirements on course directors/coordinators.† “Preparation for Teaching” and “Grading” included questions about assigning and coordinating of instructors, syllabus development, and the grading process for the course, including how the students were evaluated and what the process was by which the evaluation took place. “Evaluating the Course” gathered information about who evaluated the course and how often it was evaluated. The questionnaire also gathered the institutional equivalent of demographics, asking about the size of the medical school and the size of the library staff. A second copy of the questionnaire was sent one month later to institutions that did not return the initial questionnaire.

RESULTS

Credit course offerings

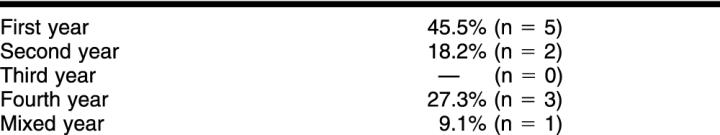

Of the 125 institutions that were surveyed, 82 responded (response rate of 65.6%). Eleven of the respondents offered at least one credit course for medical students, while 71 did not offer such a course. Of those respondents without a course, 15 (21.1%) were thinking about offering a course, 3 (4.2%) have begun to develop the course, and 1 (1.4%) has had the course approved but it has not yet been offered. There was minimal difference in terms of how many librarians were involved in teaching and whether or not a credit course was offered. The mean number of teaching librarians in libraries offering a credit course was 6.00 (SD 2.261), and the mean number of teaching librarians in libraries not offering a credit course was 5.39 (SD 3.297). Likewise, libraries with courses and those without courses did not differ in terms of the size of the medical school or the total number of professional librarians. Credit courses targeted a range of medical school years (Table 1). All years were represented except for the third year, which is not surprising as the third year of medical school tends to be occupied with required clinical rotations. Fifty-five percent of the credit courses were required, with the remaining 45% of courses elective. Variation between credit courses was greater than the variation between required courses-elective courses as groups, so the following results are for all courses. No comparisons can be made between required and elective courses.

Table 1 Medical school years in which credit courses are offered

Course and the overall scheme of courses at the institution

Of the respondents offering a credit course, 63.6% of the courses were sponsored by the library alone, and 18.2% offered the class in conjunction with another department (one respondent was in another arrangement, and another did not answer the question). Only one course sponsored solely by the library was listed in the course catalog under the library. Two were listed under medical informatics, and the others were listed under interdisciplinary studies or another option. The two courses that were cosponsored by the library and another department on campus were listed in the catalog under the cosponsoring department.

One perceived benefit to being listed in the catalog under the library or under medical informatics is that the library received the credit for the course, boosting the library's academic credibility. On the other hand, some respondents reported that these arrangements could antagonize some disciplinary faculty. In addition, the course could be overlooked in the catalog, if the category name was confusing or if the course was the only course in the category. It was also pointed out that courses listed under interdisciplinary studies could be overlooked in the catalog. Respondents whose courses were listed under cosponsoring departments reported no perceived drawbacks and identified benefits such as the course being taken more seriously by students and, in one case, having the cosponsoring department handle the promotion, registration, and course evaluation.

Learning to administer a credit course

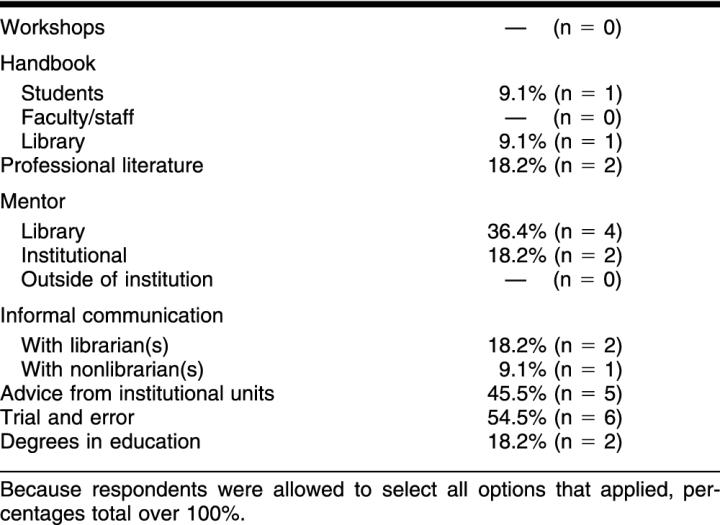

In terms of initially learning how to administer a course for credit, more than half of the respondents offering a course indicated that trial and error played a role in their education, indicating the need for published research in this area. After trial and error, advice from institutional units (such as the registrar or the department of medical education) was the next most commonly reported source of information. One librarian commented on how valuable it was to cultivate relationships with the staff members at her registrar's office, who were always willing to answer her questions. Table 2 provides a summary of how librarians indicated that they learned how to administer a course. When asked what would have made it easier to learn to administer a credit course, respondents gave a wide range of answers. Respondents without a mentor indicated that having one would have helped, while respondents with a mentor would have liked to have had written guidelines or a handbook, a fully developed plan, and a current copy of the academic schedule.

Table 2 Techniques used by librarians to learn to administer a credit course

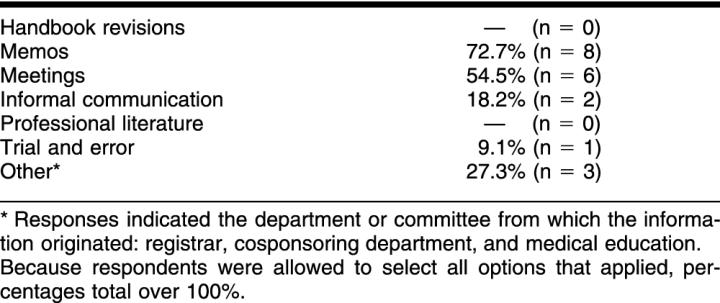

Learning how to administer a credit course is only part of the picture. Course coordinators and directors also need to be aware of policy changes that might affect the course. Most respondents learned about policy and procedure changes from memos and meetings (72.7% and 54.5%, respectively). One respondent found it helpful to attend the meetings of the clinical clerkship coordinators. While much of the discussion at these meetings focused on the required clinical clerkships, some of the information was relevant to her nonclinical elective. In addition, she also learned a great deal about the “inner workings” of her institution and issues affecting medical education. Table 3 summarizes the methods librarians used for learning about policy changes.

Table 3 Techniques used by librarians to learn about changes affecting course administration

Learning to grade was another area that was new to many course administrators, even those who had prior experience in instructional evaluation. Learning to grade has two components. First, there are institutional policies that need to be learned, such as the submission process for grades and the deadlines for grades to be submitted. There is also the act of grading itself. How do librarians learn to assess student performance? Of the respondents, 54.5% indicated that they learned how to grade by trial and error, and 36.4% indicated that they learned how to grade from coursework in education or previous experience. A smaller number of respondents learned how to grade from mentors, the professional literature, and institutional handbooks. Three respondents answered the question about what would have made it easier to grade: a workshop, an institutional handbook, and a mentor were all mentioned.

Costs associated with the course

Of the 11 respondents offering a credit course, only 2 attempted to determine the costs associated with offering a credit course. Eight respondents indicated the number of hours spent in developing the course and the number of hours spent preparing for the course each time it was offered. In terms of staff time devoted to development of the course, values ranged from 12 hours to 180 hours, with a very weak correlation (R = 0.039) between the amount of time to develop the course and the number of contact hours the course meets. There was a moderate correlation (R = 0.595) between the amount of time to prepare for the course each time it was offered and the number of contact hours.

In terms of support provided by the library for the course, all respondents indicated that the library provided preparation and teaching time, with only 45.4% reporting that their other duties were lessened. All but one respondent reported that the library provided materials preparation support. Most libraries (72.7%) provided time for professional development to improve teaching skills, with 75% of those libraries also providing funding for that purpose. One respondent's library provided other support: instructional design, graphic arts or animation, and audio/video production. Nearly all respondents indicated that they did not need to apply for any kind of institutional funding for their courses. In the one library that did need to apply for funding, the funding was for information resources and instructional space.

Relationships with other departments

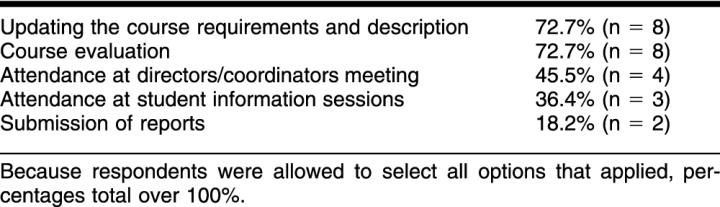

One way in which credit courses differ from other forms of IME is the library's relationships with other departments and handling of those departments' requirements. Of all the forms of IME provided by the author's institution, only the credit course requires regular contact with other departments on campus. Survey respondents varied in terms of the number of departments with which they had regular contact. All but one respondent had contact with either the medical education unit and/or the curriculum unit; these units were similar in their requirements (Table 4). Even the respondent who did not have contact with either unit was required to participate in similar activities by the cosponsoring department.

Table 4 Activities required by the medical education or curriculum unit

Six respondents (54.5%) indicated that the registrar's office required certain activities as well. Approximately 50% of these respondents processed add/drop forms, updated course requirements and descriptions, evaluated the course, and filed reports. One respondent had to handle not only local add/drop forms but also had to process forms (including grade sheets) for off-campus IME clerkships. No respondent indicated that the bursar (student financial accounts) placed requirements on the library. In institutions in which the library offered a credit course in conjunction with another department (45.5%), the cosponsoring department also imposed requirements: all were required to update requirements or descriptions and evaluate the course, with some also being required to attend student information sessions and attend course director/ coordinator meetings. In summary, all respondents offering a credit course had requirements imposed by outside departments.

Preparation for teaching and grading

In addition to dealing with outside pressures, librarians who direct or coordinate credit courses also must deal with organizing the course itself. If librarians are not going to teach classes alone, they must determine who will be teaching the course. In some institutions, the library administration selects the instructors. Two respondents (18.2%) indicated that administration made the choice. One of the two indicated that this was driven by the faculty status recently awarded to the librarians, and the administration wanted to make sure that teaching duties were distributed to assist librarians in this new role. Twenty-seven percent of the respondents indicated that the instructors were self-selected, and 54.5% of institutions relied upon the course director/coordinator to decide. As with all forms of instruction, course director/coordinators must consider that the instructors and the ways the instructors are selected can have an impact on quality of instruction, especially if librarians who do not want to teach (or who may be poor teachers) are forced to teach.

Once instructors are selected, there is the question of who will coordinate the instructors. Not surprisingly, most respondents (90.9%) indicated that the course director/coordinator was responsible for coordinating the instructors. In only one institution did the instructors coordinate themselves. Coordinating multiple instructors can be challenging, especially as they develop and improve their sessions. One respondent reported on a situation in which one librarian inadvertently infringed on another librarian's subject area and commented on the importance of the director/coordinator communicating regularly with the instructors (either individually or in group meetings) to know what changes are being made and how those changes might affect other instructors.

Development of a syllabus (including the selection of readings) often falls on the course director/coordinator (54.5% of respondents), with the instructors also taking on the role (36.4%). Though teaching librarians often have experience writing objectives, their experience with syllabi may only have been as recipients. At one responding institution, the initial syllabus was based on syllabi from courses taken by the course coordinator. The resulting document was barely functional for the course. She and the other librarians involved in creating the elective assumed incorrectly that students would be able to complete the assigned project and write it up as expected. Upon reflection on the syllabus and the submitted projects, the coordinator realized that the syllabus was asking for a type of writing that most students had not previously done. To correct this, the librarians rewrote the description of the project in more detail and included specific questions that the students should address in their projects. Given this extra guidance, the quality of students' projects improved greatly, illustrating an instructional precept: do not make the students play “guess what the teacher is thinking.”

Eight of the respondents (72.7%) indicated that their courses were graded pass/fail, satisfactory/unsatisfactory, or some other dichotomous structure, while the remaining respondents used letter grades or a similar multilevel structure. There was no consistent pattern in the questionnaire responses as to how student grades are determined. Most respondents (81.8%) considered a variety of aspects such as attendance, participation, homework, quizzes and exams, and capstone projects. One relied solely on midterms and finals and one solely on the capstone project. In only 18.2% of institutions was the course director/coordinator alone responsible for grading students. The remaining respondents indicated that grading was done by some combination of the course instructors.

Evaluation of course

Of the respondents offering a credit course, 90.9% indicated that evaluation of the course was required by departments outside of the library. Even the respondent who was not required by an outside department to evaluate the course did so. Eighty-one percent of the respondents utilized multiple information sources for evaluation, such as students, instructors, or course directors/coordinators, as well as people outside of the course, such as other librarians. Overall, institutions evaluated the course at least once a year, with institutions that offered the course more than once a year evaluating it each time the course was offered. The most complex evaluation scheme reported was a combination of the instructor evaluating each class, the students evaluating it at the end of the course, and the instruction team (director/coordinator and instructors) meeting once a year to evaluate the course and discuss modifications for the upcoming year. All respondents reported evaluating the content of the course, the practicality of the content, and the course assignments, with 72.7% also evaluating the instructors. Evaluation of the grading scheme and classroom environment were each indicated by 36.4% of respondents.

DISCUSSION

Because of the small number of respondents that offer a course for credit and the wide variation in institutional policies, requirements, and politics, it is difficult to make generalizations. Two important issues were highlighted by this research project. First, credit courses offered by libraries involve a great deal more work than traditional forms of information management education, not only in the preparation for teaching and the teaching itself, but also in learning how to administer a course and dealing with responsibilities imposed by other units on campus. Secondly, course directors/coordinators must be prepared to navigate the institutional and/or medical school politics that come hand-in-hand with providing educational opportunities outside of traditional library-based information management education. Some recommendations for librarians thinking about or planning a credit course were generated by this project.

Consider the obvious and not-so-obvious goals of offering a credit course

The obvious goals of such a course are the ability to provide students with knowledge and skills that will serve them in their careers and to provide students with the opportunity to earn credit toward graduation. Not-so-obvious goals may be to increase the campus visibility of the library, to support the teaching roles of faculty librarians, and to provide librarians with another avenue of interacting with disciplinary faculty. Take advantage of the knowledge of library administration when attempting to identify the not-so-obvious goals of a credit course.

Work within the political confines as best you can

Carefully assess the institutional or medical school climate to determine if there are multiple ways of situating a credit course. Should the library offer it alone or together with another department? If there are options, consider the pros and cons of each. Which will give the greatest return on investment of time and effort? If there is only one way to offer it and it is not optimum, should the course be developed and offered anyway, with hopes that a better method or other opportunities might open up in the future?

Gather information from a variety of sources

When it is decided to pursue the development of a credit course, gather information from a wide range of sources—from both the institution and the greater community of librarians. Seek ideas, feedback, and support from others. As one respondent stated, “It would have been nice to know ahead of time that feeling crazy was a normal part of the process.” It is impossible to avoid all trial-and-error learning, but it can be minimized. Take advantage of other librarians' experience. Two useful mailing lists are the Information Management Education Special Interest Group's imesig@yahoogroups.com (a currently quiet group sponsored by a special interest group of the MLA Public Services Section, consisting of health sciences librarians interested in an assortment of information management education activities‡) and the Instruction Services List at ILI-L@ala.org (an information literacy instruction list sponsored by the Instruction Section of the Association of College and Research Libraries, with members providing information management education at a wide range of institutions, including health sciences libraries§).

Know what information and tasks are required by which campus units by what deadlines

Some institutions clearly describe the requirements to course directors and coordinators, while others are less forthcoming. Some provide information for clinical courses, which may or may not be relevant for nonclinical courses. Take advantage of all forms of communication to learn what is needed and to keep abreast of policy and procedure changes: memos, handbooks (including student handbooks), emails, meetings, and informal communications. Make friends in other departments; when directing or coordinating a course, there is nothing better than having an understanding colleague in the registrar's office, for example, to turn to for guidance.

If multiple instructors are teaching the course, they should be in regular contact with one another

A meeting of all instructors should be held at least once a year to provide a time when they can evaluate the course, share problems and solutions, report on improvements made to content, share ideas for revisions, and discuss other course-related issues. In addition to the meetings, the director/coordinator should serve as the clearinghouse of course information and be informed of all changes when they occur. This will help minimize problems with instructors encroaching on other instructors' content areas.

Keep careful records of course materials as they evolve

Copies of older syllabi, handouts, lesson plans, and so on are useful in evaluating credit courses: what changes were beneficial and which were not? Which improved student learning and what types of students did they help? When evaluating student outcomes, it can also be helpful to keep copies of student work, so that old syllabi can be matched up with sample student projects. Finally, it is recommended that librarians take time to create and maintain an in-library manual about the credit course for use by their successors.

CONCLUSIONS

When the institutional and medical school climate is appropriate, librarians may feel that adding a credit course to their repertoire of information management education for medical students is worth the time and effort administering such a course takes. It is important for librarians seeking this opportunity to be prepared to learn a new way of interacting with other departments on campus. It is also important to remember that credit courses are not the be-all and end-all of information management education. They offer benefits to both the students and the librarians, but they are only one part of a wide range of educational activities that can be provided by librarians. There are many avenues for providing information management education to medical students.

APPENDIX

Questionnaire for identifying issues surrounding the administration of a credit course in schools of medicine

Instructions: For each question, unless otherwise instructed, circle the option that best reflects your answer. Following a set of questions, there is space for you to add written comments. In addition, there is an option on the final page of the survey for you to indicate if you are interested in being contacted by the researcher to share your experiences in depth.

Institutional information

How many medical students are enrolled in the first year of your medical school? ____________

How many professional librarians (those with master's degrees) are on your staff? ____________

-

How many of these professional librarians teach in a structured setting, such as a class or training session? (Do not include those librarians who only provide point-of-service instruction at a service desk.) ____________

Credit course offerings.

-

Does your library offer a credit course for medical students at your institution?

a. Yes, go to question 6

b. No, go to question 5

-

If not, what are your plans for the future in terms of offering a credit course?

a. No plans to offer any credit course

b. Thinking about offering such a course

c. Have begun to develop such a course

d. Course proposal has been submitted to an institutional curriculum committee for approval

e. Course has been approved but not yet offered

Thank you for your time. Please go to the final page of this questionnaire.

What is the name of the credit course for medical students offered by your library? (Please print.) ________________________________________________________________________

-

What level(s) of medical students are enrolled in the course? (Circle all that apply.)

a. First year

b. Second year

c. Third year

d. Fourth year

e. Other (Please specify __________________)

-

Is the course required or elective?

a. Required

b. Elective

-

How long has your library offered a credit course?

a. Less than 1 year

b. 1–2 years

c. 3–4 years

d. 5–10 years

e. Over 10 years

-

What is the duration of the course?

a. 1 week

b. 2–3 weeks

c. 4–6 weeks

d. Quarter

e. Semester

f. Other (Please specify __________________)

How many contact hours does the course meet each time it is offered? ____________

How many times per academic year is the course offered? ____________

-

Who determines when the course will be offered?

a. Course coordinator/director

b. Registrar's office

c. The school or department in which the course is listed

d. Other (Please specify __________________)

Course and the overall scheme of courses at the institution.

-

Does your library offer the credit course alone or in conjunction with another department?

a. Alone

b. In conjunction with another department (Please specify __________________)

c. Other arrangement (Please specify __________________)

-

Under which department is your course listed in the course catalog?

a. Library

b. Medical informatics

c. Cosponsoring department

d. Interdisciplinary studies

e. Other (Please specify __________________)

What benefits are there to having the course listed here? ____________

-

What drawbacks are there to having the course listed here? ____________

Learning to administer a credit course.

-

How did you first learn about administering a credit course? (Circle all that apply.)

a. Workshop held by the institution for students

b. Workshop held by the institution for faculty/staff

c. Workshop held outside the institution

d. Handbook produced by the institution for students

e. Handbook produced by the institution for faculty/staff

f. Handbook produced by the library

g. Professional literature

h. Mentor within the library

i. Mentor within the institution, outside the library

j. Mentor outside of the institution

k. Informal communication with other librarians who administer a credit course

l. Informal communication with nonlibrarians who administer a credit course

m. Advice from institutional units (registrar, curriculum committee, student affairs, etc.)

n. Trial and error

o. Other (Please specify __________________)

-

How do you learn about policy and procedure changes regarding credit courses at your institution? (Circle all that apply.)

a. Handbook revisions

b. Memos

c. Meetings

d. Informal discussion with others who administer credit courses

e. Professional literature

f. Trial and error

g. Other (Please specify __________________)

What would have made it easier for you to learn how to administer a credit course? ____________

-

What is your role in relation to the credit course offered by your library? (Circle all that apply.)

a. Course director

b. Course coordinator

c. Course developer

d. Instructor

e. Other (Please specify __________________)

-

Because the responsibilities for these roles vary among institutions, list the your main duties related to administration of the course.

Costs associated with the course.

-

Has your library attempted to determine the cost of offering a credit course?

a. Yes

b. No

c. I don't know

-

How much staff time (in hours) do you estimate it took to develop this course? (Consider the time of all librarians involved.) ____________

Don't know ____________

-

How much staff time (in hours) do you estimate is needed each time the course is taught? (Consider preparation and teaching time for all librarians involved.) ____________

Don't know ____________

-

What types of support does your library provide for the course? (Circle all that apply.)

a. Preparation time for librarians

b. Teaching time for librarians

c. Lessening of other duties

d. Materials preparation (photocopying, spiral binding, overheads, etc.)

e. Time for professional development sessions to improve skills such as teaching, assessment, etc.

f. Financial support for to take professional development sessions

g. Other (Please specify __________________)

-

At any time, did the library have to apply for institutional funding for this course?

a. Yes, go to question 28

b. No, go to question 29

c. I don't know, go to question 29

-

For what aspects of the course was funding required? (Circle all that apply.)

a. Hardware (computers, projection equipment)

b. Software (productivity software, bibliographic management software)

c. Information resources (books, online resources)

d. Staff time (preparation, teaching)

e. Instructional space (classrooms, computer labs)

f. Other (Please specify __________________)

Relationships with other departments.

-

With which departments outside of the library do you have regular contact regarding your course? (Regular contact is defined as at least one contact per academic year.)

a. Medical education unit (department, office, etc.)

b. Curriculum unit (committee, office, etc.)

c. Registrar

d. Bursar (student financial accounts)

e. Academic department(s) with which the course is offered (cosponsoring department)

f. Other (Please specify __________________)

-

What activities does the medical education unit require of you in relation to the course?

a. Update course descriptions/requirements

b. Attend student information sessions to promote course

c. Evaluate the course

d. Attend course coordinator/director meetings

e. File reports

f. Other (Please specify __________________)

g. The medical education unit does not impose any required activities

-

What activities does the curriculum unit require of you in relation to the course?

a. Update course descriptions/requirements

b. Attend student information sessions to promote course

c. Evaluate the course

d. Attend course coordinator/director meetings

e. File reports

f. Other (Please specify __________________)

g. The curriculum unit does not impose any required activities

-

What activities does the registrar require of you in relation to the course?

a. Processing add/drop forms

b. Processing paperwork for off-campus courses similar to the one you offer (away clerkships)

c. Update course descriptions/requirements

d. Attend student information sessions to promote course

e. Evaluate the course

f. Attend course coordinator/director meetings

g. File reports

h. Other (Please specify __________________)

i. The registrar does not impose any required activities

-

What activities does the bursar (student financial accounts) require of you in relation to the course?

a. Update course descriptions/requirements

b. Attend student information sessions to promote course

c. Evaluate the course

d. Attend course coordinator/director meetings

e. File reports

f. Other (Please specify __________________)

g. The bursar does not impose any required activities

-

What activities does the cosponsoring academic department require of you in relation to the course?

a. Update course descriptions/requirements

b. Attend student information sessions to promote course

c. Evaluate the course

d. Attend course coordinator/director meetings

e. File reports

f. Other (Please specify __________________)

g. The cosponsoring academic department does not impose any required activities

h. There is no cosponsoring department for this course

-

Describe requirements imposed by any other campus department(s).

Preparation for teaching.

-

Who was primarily responsible for selecting the instructors for the course?

a. Course coordinator/director

b. Library administration

c. Self-selected

d. I am the only instructor for this course

e. Other (Please specify __________________)

-

Who is responsible for coordinating the instructors?

a. Course coordinator

b. Course director

c. Course instructor(s)

d. Other (Please specify __________________)

-

Who was responsible for selecting the textbook/ readings for the course?

a. Course coordinator

b. Course director

c. Course instructor(s)

d. Other (Please specify __________________)

-

Who was responsible for creating the syllabus?

a. Course coordinator

b. Course director

c. Course instructor(s)

d. Other (Please specify __________________)

Grading.

-

How is this course graded?

a. Pass/fail; credit/no credit; pass/no pass

b. Letter grades or similar structure (honors, high pass, pass, fail)

c. Other (Please specify __________________)

-

On what basis are students graded in this course? (Circle all that apply.)

a. Attendance

b. Participation

c. In-class activities

d. Homework

e. Quizzes or midterm examinations

f. Midterm papers or projects

g. Final examination

h. Final/capstone paper or project

i. Other (Please specify __________________)

-

How was the grading scheme determined?

a. By the course developer(s)

b. By the course coordinator/director

c. By the course instructors

d. Determined by the cosponsoring department

f. Other (Please specify __________________)

-

Who determines the overall grades of the students?

a. Course coordinator/director

b. All of the faculty teaching the course

c. Some of the faculty teaching the course

d. Other (Please specify __________________)

-

If you take part in the grading, how did you learn to grade? (Circle all that apply.)

a. Workshop held by the institution

b. Workshop held by the library

c. Workshop held outside of the institution

d. Handbook produced by the institution

e. Handbook produced by the library

f. Handbook produced outside the institution

g. Professional literature

h. Mentor within the institution

i. Mentor within the library

j. Mentor outside of the institution

k. Trial and error

l. Other (Please specify __________________)

-

What would have made it easier for you to learn how to grade student performance?

Evaluating the course.

-

Who evaluates the course? Circle all that apply.

a. Course coordinator/director

b. Instructors

c. Students

d. Someone outside of the course

e. No one

f. Other (Please specify ____________)

-

How often is the course evaluated? (Circle all that apply.)

a. At every class session

b. At the end of the course

c. Twice a year

d. Once a year

e. Every couple of years

f. Never

g. Other (Please specify ____________)

-

What components of the course are evaluated? Circle all that apply.

a. Course content (in general)

b. Practicality of course content

c. Assignments

d. Grading scheme

e. Classroom environment

f. Instructor(s)

Written comments (please use additional paper if necessary).

________________________________________________________________________

Optional: If you are interested in speaking with the researcher about your experiences as a librarian administering a credit course, please fill out this section:

Name: _____________________________ Phone: _____________________

Library: ___________________________ Fax: ________________________

Institution: _______________________ Email: _____________________

Please return this questionnaire in the enclosed self-addressed stamped envelope to Jolene M. Miller, MLS, Reference/Education Librarian, Raymon H. Mulford Library, Medical College of Ohio, 3045 Arlington Avenue, Toledo, OH 43614-58005.

Footnotes

* This project was supported by a Medical Library Association Research, Development, and Demonstration Project Grant.

† Because of institutional differences in the roles of course directors and course coordinators, “director/coordinator” is used to refer to those individuals who are responsible for managing the course, regardless of their titles.

‡ More information about the Information Management Education Special Interest Group's list is available at http://groups.yahoo.com/group/imesig/.

§ More information about the Instruction Services List is available at http://www.ala.org/ala/acrlbucket/is/ilil.htm.

REFERENCES

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical school objectives project: medical informatics objectives. [Web document]. Washington, DC: The Association, 1998. [rev. Jan 1998; cited 28 Jun 2002]. <http://www.aamc.org/meded/msop/start.htm>. [Google Scholar]

- Adams MS, Morris JM. Teaching library skills for academic credit. Phoenix, AZ: Oryx Press, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bradigan PS, Mularski CA. End-user searching in a medical school curriculum: an evaluated modular approach. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1989 Oct; 77(4):348–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahmi F, London S, Emmett T, Barclay A, and Kaneshiro K. Teaching life-long learning skills in a fourth-year medical curriculum. Med Ref Serv Q. 1999 Sum; 18(2):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman GE, Mueller MH. Credit course for medical students. Med Ref Serv Q. 1985 Fall; 4:61–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hannigan GG, Bartold SP, and Browne BA. Computers and medical information: an elective for fourth-year medical students. Med Ref Serv Q. 1996 Win; 15(4):81–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman C, Conway S, and Gallagher K. Health information resources: tradition and innovation in a medical school curriculum. Med Ref Serv Q. 1999 Spr; 18(1):11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller MH, Foreman G. Library instruction for medical students during a curriculum elective. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1987 Jul; 75(3):253–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association of American Medical Colleges. AAMC data book. Washington, DC: The Association, 2000. [Google Scholar]