Abstract

Background: Structured abstracts were introduced into medical research journals in the mid 1980s. Since then they have been widely used in this and other contexts.

Aim: The aim of this paper is to summarize the main findings from research on structured abstracts and to discuss the limitations of some aspects of this research.

Method: A narrative literature review of all of the relevant papers known to the author was conducted.

Results: Structured abstracts are typically longer than traditional ones, but they are also judged to be more informative and accessible. Authors and readers also judge them to be more useful than traditional abstracts. However, not all studies use “real-life” published examples from different authors in their work, and more work needs to be done in some cases.

Conclusions: The findings generally support the notion that structured abstracts can be profitably introduced into research journals. Some arguments for this, however, have more research support than others.

INTRODUCTION

Readers of this article will have noted that the abstract is set in a “structured” format. Such abstracts typically contain subheadings and subsections—such as “background,” “aim(s),” “method(s),” “results,” and “conclusions”—and provide rather more detail than do traditional ones. Furthermore, these features are clarified by the typographic layout. Structured abstracts are more common in articles describing experimental research but, as the example above indicates, they can also be used with reviews.

Structured abstracts were introduced into medical journals in the mid 1980s [1], and, since then, their growth has been phenomenal [2]. Indeed, they are now commonplace in all serious medical research journals. Furthermore, their use has been recommended, and indeed is growing, in other scientific areas [3–8]. Structured abstracts can be found in American, European, Australian, Japanese, and Chinese journals [9]. In addition, some academic societies now require contributors to send potential conference submissions in this format. The British Psychological Society, for instance, has dispensed with the need for the three-to-four page summaries previously required from potential participants and now publishes the accepted structured abstracts in their Conference Proceedings [10].

KEY FINDINGS

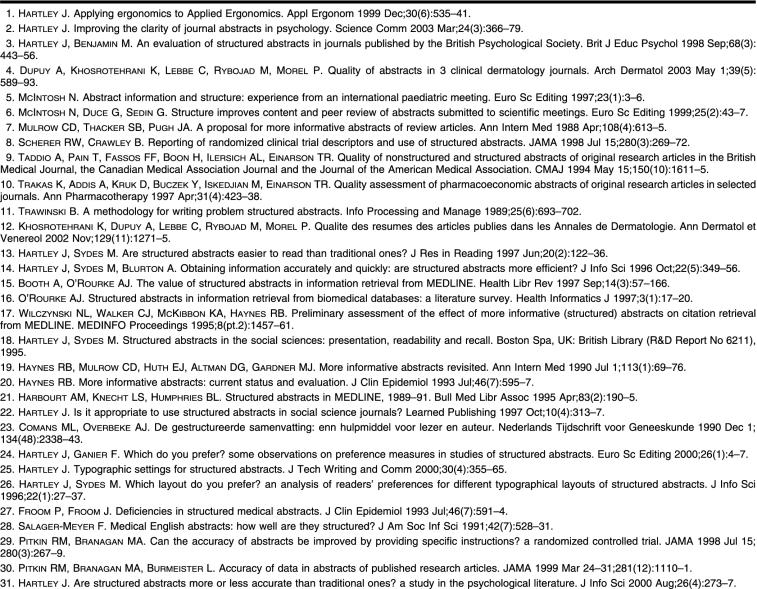

The case for using structured abstracts in scientific journals has been bolstered by research, most of which has taken place in a medical or a psychological context. Table 1 lists all of the research studies on the topic known to the author at the time of writing.

Table 1 List of studies referred to in this paper

The results from these studies suggest that, compared with traditional ones, structured abstracts:

contain more information (studies 1–11), but not always so (study 12);

are easier to read (studies 2, 3, 13);

are easier to search (studies 3, 14), although some authors have questioned this (studies 15–17);

are possibly easier to recall (study 18);

facilitate peer review for conference proceedings (studies 5, 6, 19); and

are generally welcomed by readers and by authors (studies 1–3, 11, 19, 20).

However, there have been some qualifications. Structured abstracts:

usually take up more space (studies 1–4, 7, 11, 13, 21–24);

sometimes have confusing typographic layouts (studies 25, 26); and

may be prone to the same sorts of omissions and distortions that occur in traditional abstracts (studies 8–10, 27–31).

SOME OBSERVATIONS

Although these findings seem clear-cut, some problems with the research in general need to be taken into account. Two main issues exist. First, but possibly not too important, is that many studies have used undergraduate students as participants, rather than postgraduates or fully fledged academics. Such undergraduates, of course, do not have the experience of full-time academics and post-graduates in reading journal abstracts, and thus the requirements of the studies may be rather different for them. Second, and much more important, is that not all of the studies have compared actual, previously published, traditional and structured abstracts, thus reducing the validity of the comparisons.

For a study to be properly valid in this context, one needs, in effect, to compare, from a particular journal, sets of published traditional abstracts with sets of (different/later) published structured abstracts. What has often happened in practice, however, is that either the structured versions of published traditional abstracts have been written independently by the researchers for the studies in question (studies 1, 2, 11), or the published traditional abstracts have been shortened and simplified for experimental purposes, and then structured versions of these simplified versions have been written by the researchers (studies 13, 14, 18). The main reason for this state of affairs stems from the fact that the researchers in question are often advocating the use of structured abstracts in a particular discipline where none (or very few) are available at the time of writing, and thus they have had to create their own. Such procedures do not destroy the validity of the findings, but they do limit their generality. To be properly valid, the abstracts need to be written by the authors of the articles and not by the researchers.

Applying these considerations to the findings listed above, then:

It is not surprising that most studies find that structured abstracts contain more information than traditional ones. If researchers create structured abstracts from traditional ones, then it is likely that they will increase the amount of information that they provide when they are doing this. The best evidence to support the argument that structured abstracts contain more information than traditional ones comes from studies comparing published abstracts in both formats from the same journal or journals written by independent authors. Such studies that meet these requirements (studies 4, 5, 8–10, 12, 21) all support the view (with the exception of study 12) that structured abstracts are more informative than are traditional ones.

It is also perhaps not so surprising that structured abstracts appear easier to read than traditional ones, if the structured abstracts are revisions of the traditional ones (studies 1, 2, 11). Again, the best test of this readability hypothesis would come from studies comparing separately published abstracts in both formats. But no such studies on this issue have been reported.

Similarly, if the structured abstracts are revisions of simplified traditional ones, then it is perhaps not surprising that they are easier to search (study 14). Studies with the more complicated “real-life” abstracts presented in MEDLINE have not shown an advantage for search speed (studies 15, 17).

Virtually no studies have been done on the recall of traditional and structured abstracts to find out whether or not structured abstracts are remembered any better than traditional ones. Six “miniature” studies outlined by Hartley and Sydes (reported in study 18) suggested that this was the case, when the structured abstracts were longer and were more readable than the traditional ones. However, this was not the case when the abstracts were equated for length and readability. Furthermore, these six studies were done with simplified versions of published abstracts, using students as participants. Research in other contexts suggests that structured text might be better recalled than text in traditional formats [11], although some people have argued that because less well-structured text requires more processing, it might subsequently be remembered better.

Suggestions about the benefits of using structured abstracts for selecting conference papers are rarely evidence based. They simply suggest their usefulness in this respect. One exception is the study by McIntosh, Duc, and Sedin (study 6). These authors reported that referees were less frustrated reviewing the information content and deciding on the suitability of a conference submission when they judged resubmitted structured abstracts compared with traditional ones.

Most studies of readers' reactions to structured versus traditional abstracts have in fact relied on the judgments of academics rather than students (studies 2, 3, 6), but few have been asked to judge independently published versions of both sets.

If structured abstracts do present more information, it is not surprising that they are usually longer than traditional ones. These 2 measures are correlated. The weighted average increase in length for the structured abstracts in the first 11 studies listed in Table 1 is 21%. However, 8 of these studies used simplified and/or especially written abstracts for the purpose of illustration. In the 3 studies that compared independently published abstracts and provided data on this measure, the structured abstracts were 40%, 30%, and 29% (weighted average 35%) longer than the traditional ones, respectively (studies 3, 21, 23).

There is, as yet, no hard information on whether or not structured abstracts contain less—or more—omissions, distortions, and errors than do traditional ones. Nonetheless, several authors have reported omissions in the published structured abstracts in the medical journals that they studied (studies 8–10, 27, 28). Hayes et al. (study 19) argued that structured abstracts might have fewer errors than traditional ones, but Pitkin and his colleagues (studies 29, 30) argued the reverse of this because of their extra length. But none of these authors have made direct comparisons. Hartley (study 31) found no differences in the degrees of distortion or errors between traditional and structured abstracts, but his structured abstracts were rewritten versions of traditional ones. So, to date, no one to the author's knowledge has compared the accuracy of separately published traditional and structured abstracts.

CONCLUSIONS

The literature reviewed in the first part of this paper suggests that structured abstracts are an improvement over traditional ones. However, as argued in the second part, the evidence used to support these claims is sometimes not as good as we might wish. In particular, we have to judge the applicability of the findings from this research to the “real world.” The explosion in the use of structured abstracts, particularly in the medical context, suggests that these judgments have already been made.

Some editors have complained that structured abstracts “take up too much space.” Indeed, the data reviewed in this paper from the more valid studies suggest that the extra space required by introducing structured abstracts may be quite considerable. But we have to remember here that we are only talking about the extra line-space required by the abstract and not the article as a whole. Indeed, setting a word limit (such as 200 words as in the Journal of the Medical Library Association) could control this amount. Whatever the case, introducing structured abstracts into a journal is unlikely to require changes in the overall pagination. There is often “free” space at the ends of articles, and typesetters are skilled at fitting text to appropriate page dimensions [12]. Such concerns, of course, do not arise with electronic journals and databases.

Some authors—and some editors too—have also complained that the formats for structured abstracts are too rigid and that they present them with a straightjacket that is inappropriate for all journal articles. Undoubtedly, this may be true in some circumstances, but it is remarkable how in fact the subheadings used in this present article can cover a variety of research styles. The Research Results Dissemination Task Force of the Medical Library Association's Research Section, for example, provides suggested subheadings for experimental studies, qualitative studies, case reports, and reviews, all of which follow to some degree or other the basic format used here [13]. Furthermore, if readers care to examine current practice (or Table 4 in Hartley's 2000 Bulletin of the Medical Library Association paper [14]), they will find that even though the subheadings used here are typical, they are not rigidly adhered to. Editors normally allow authors leeway in the subheadings that they use.

Finally, we might note that the research on structured abstracts is limited in two other ways. First, it is not clear in many studies whether or not the titles of the journal articles have been presented along with the abstracts, and clearly a title might help the reader to recall and possibly interpret the text under study [15]. Second, no one to the author's knowledge has studied complete articles with either traditional or structured abstracts. Here, where the abstract plays a small, but nonetheless important, role, it would be of interest to see if the format of the abstract affects the readers' judgments of the quality of an article (or even of a journal) as a whole.

Despite these limitations, and the ones discussed earlier, the conclusions of this review are that the data discussed above do support the claim that structured abstracts are an improvement over traditional ones. Not only is more information presented, which is helpful for the reader, but also the format requires that the authors organize and present their findings in a systematic way. Furthermore, this consistency is made more obvious by the typographic layout. Advances in “text mining,” “research profiling,” and computer-based document retrieval systems can only profit from the use of these more informative abstracts.

REFERENCES

- Ad Hoc Working Group for Critical Appraisal of the Medical Literature. A proposal for more informative abstracts of clinical articles. Ann Intern Med. 1987 Apr; 106(4):598–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbourt AM, Knecht LS, and Humphries BL. Structured abstracts in MEDLINE, 1989–91. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1995 Apr; 83(2):190–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley J. Is it appropriate to use structured abstracts in social science journals? Learned Publishing. 1997 Oct; 10(4):313–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley J. Is it appropriate to use structured abstracts in non-medical science journals? J Info Sci. 1998 Oct; 24(5):359–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley J. Applying ergonomics to Applied Ergonomics. Appl Ergonom. 1999 Dec; 30(6):535–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley J. Clarifying the abstracts of systematic reviews. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000 Oct; 88(4):332–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley J. Improving the clarity of journal abstracts in psychology. Science Comm. 2003 Mar; 24(3):366–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kostoff N, Hartley J.. Open letter to technical journal editors. J Info Sc. 2002;28(3):257–61. [Google Scholar]

- Liu XL, Qiano HC, Bo-Rong P, Jun D, and Su-Juan W. Structured abstracts in Chinese biomedical journals: the current situation and perspective. Euro Sci Editing. January1993 (48). 20. [Google Scholar]

- British Psychological Society. Centenary Annual Conference: final programme and abstracts. Leicester, UK: British Psychological Society, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley J. Recalling structured text. does what goes in determine what comes out? Brit J Ed Technol. 1993 May; 24(2):84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley J. Do structured abstracts take up more space? and does it matter? J Info Sci. 2002 Oct; 28(5):417–22. [Google Scholar]

- Evidence Based Librarianship Implementation Committee. Research results dissemination task force recommendations. Hypothesis. 2002 Spring; 16(1):6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley . 2000. op. cit. [Google Scholar]

- For the record: titles and introductions. Teachers College Record 2000 102(3):447–79. [cited 18 Jun 2003]. <http://www.tcrecord.org>. [Google Scholar]