Abstract

Knowledge of concentrations and elemental ratios of suspended particles are important for understanding many biogeochemical processes in the ocean. These include patterns of phytoplankton nutrient limitation as well as linkages between the cycles of carbon and nitrogen or phosphorus. To further enable studies of ocean biogeochemistry, we here present a global dataset consisting of 100,605 total measurements of particulate organic carbon, nitrogen, or phosphorus analyzed as part of 70 cruises or time-series. The data are globally distributed and represent all major ocean regions as well as different depths in the water column. The global median C:P, N:P, and C:N ratios are 163, 22, and 6.6, respectively, but the data also includes extensive variation between samples from different regions. Thus, this compilation will hopefully assist in a wide range of future studies of ocean elemental ratios.

Background & Summary

One of the fundamental tenets of ocean biogeochemistry is the Redfield ratio. Redfield identified a similarity between the N:P ratio of plankton living in the surface ocean and that of dissolved nitrate and phosphate in the deep ocean1,2. He hypothesized that the deep ocean nutrient concentrations were controlled by the elemental requirements of the surface plankton. This concept has been extended to include other elements like carbon and remains a cornerstone for our understanding of ocean biogeochemistry. Despite the importance of this ratio, there is no obvious mechanism for a globally consistent C:N:P ratio of 106:16:1 (i.e., Redfield ratio), and there is substantial elemental variation among ocean taxa3–6. Furthermore, many small plankton are not homeostatic but instead, the cellular elemental content varies depending on growth conditions7. Thus, it has become apparent that changes in biodiversity or cell physiology can lead to variations in marine plankton elemental stoichiometry.

Variations in elemental content and ratios of marine microbial communities have multiple important implications. Broecker and Henderson have proposed that increased plankton C:N:P ratios and thus increased CO2 uptake in the ocean could explain the glacial to inter-glacial variation in atmospheric CO2 concentration8. Rates of N2 fixation as well as competition between phytoplankton and N2-fixers are also dependent upon an assumed N:P ratio (specifically the Redfield ratio). Recently, multiple researchers have argued that our understanding (or lack thereof) of cellular elemental stoichiometry has a large influence on our ability to estimate the global ocean N budget9,10.

It has been observed that specific phytoplankton groups as well as particulate organic matter display regional differences in elemental stoichiometry11–14. For example, the C:P, N:P, and C:N ratios all appear to be above Redfield proportions in the oligotrophic gyres, near Redfield proportions in upwelling regions like the Eastern Equatorial Pacific Ocean, and below Redfield proportions in colder, nutrient rich high latitude environments11,12. The ratios may also vary between the gyres depending on the nutrient supply ratio and the resulting degree of nitrogen versus phosphorus limitation. Thus, rather than globally static C:N:P ratios, differences in environmental conditions and plankton community composition can lead to variations in the elemental composition of plankton and particulate organic material4,11–13,15. In addition, we also observe extensive variations in the ratios of particulate nutrients which cannot be explained with common physio-chemical parameters11,12. Thus, future studies are needed to identify factors causing this variation.

The elemental stoichiometry of ocean plankton communities has also been the focus in many model studies10,15–17. This includes models describing cellular elemental composition in response to changes in light intensity, nutrients, or other environment conditions16,17. Other models focus on identifying regional differences in the elemental stoichiometry15. Thus, models have indicated that the elemental stoichiometry of cells, communities, and ocean regions are not constant but vary depending on biodiversity and environmental conditions. However, we currently do not have global datasets to evaluate the output of such models.

To address this issue, we here present a compilation of measurements of marine particulate organic carbon (POC), nitrogen (PON), and phosphorus (POP) from 70 cruises or time-series during the last 40 years (Table 1 (available online only))12,18–67. The dataset includes a total of 100,605 discrete measurements of particulate organic nutrients including 6940 POP, 46728 PON, and 46937 POC measurements. This leads to 5948 N:P, 5573 C:P, and 45476 C:N observations. Due to the common concurrent and largely automated measurements of PON and POC, these two particulate nutrients are over-represented in comparison to the sparse measurements of POP.

Table 1. Summary of cruises and time-series in this dataset including number of stations and POM samples as well as the mean elemental ratios.

| Cruise | #Sta | Year |

Latitude

|

Longitude

|

POC | PON | POP | C:P * | N:P | C:N | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| min | max | min | max | (#samples) | |||||||||

| AMT1 | 23 | 1995 | −51 | 49 | −57 | −9 | 23 | 23 | — | — | — | 8.0 | 18 |

| AMT10 | 42 | 2000 | −35 | 49 | −49 | −6 | 57 | 57 | — | — | — | 9.5 | 19 |

| AMT12 | 14 | 2003 | −38 | 45 | −38 | −19 | 72 | 72 | — | — | — | 8.3 | 18 |

| AMT13 | 10 | 2003 | −36 | 40 | −34 | −18 | 50 | 50 | — | — | — | 7.7 | 18 |

| AMT14 | 15 | 2004 | −47 | 49 | −50 | −16 | 71 | 78 | — | — | — | 7.0 | 18 |

| AMT15 | 21 | 2004 | −40 | 39 | −25 | 10 | 100 | 100 | — | — | — | 8.7 | 18 |

| AMT16 | 32 | 2005 | −32 | 47 | −46 | 17 | 191 | 191 | — | — | — | 12 | 18 |

| AMT17 | 33 | 2005 | −35 | 49 | −39 | 14 | 178 | 178 | — | — | — | 9.0 | 18 |

| Antares3 | 20 | 1995 | −59 | −48 | 62 | 74 | 146 | 146 | — | — | — | 8.8 | 20 |

| Antares4 | 25 | 1999 | −46 | −43 | 62 | 65 | 364 | 356 | — | — | — | 8.0 | 21 |

| ANTVI | 61 | 1992 | −60 | −47 | −50 | −6 | 582 | 582 | — | — | — | 6.7 | 22 |

| ANTXXIII | 26 | 2005 | −26 | 50 | −21 | 9 | 120 | 120 | — | — | — | 7.6 | 23 |

| Arabesque | 14 | 1994 | 8 | 19 | 58 | 67 | 70 | 52 | — | — | — | 7.0 | 24 |

| Atlantic | 4 | 1973 | 31 | 31 | −10 | −10 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 110 | 17 | 6.6 | 25 |

| Atlantic Ocean | 160 | 1990–95 | 24 | 61 | −65 | −10 | 1174 | 1174 | — | — | — | 10 | 24 |

| ATP3 | 13 | 2006 | 21 | 32 | −66 | −64 | 129 | 129 | 130 | 297 | 56 | 5.3 | 12 |

| BATS | 73 | 2003–10 | 31 | 32 | −64 | −64 | 722 | 722 | 661 | 188 | 36 | 5.2 | 26 |

| Bering Sea | 75 | 2009–10 | 54 | 63 | −179 | −161 | 291 | 272 | 296 | 84 | 9.8 | 8.1 | 12 |

| BIOSOPE | 21 | 2004 | −35 | −8 | −141 | −73 | 162 | 156 | 164 | 171 | 21 | 7.9 | 27 |

| BloomER | 2 | 2007 | 23 | 24 | −159 | −159 | 16 | 16 | — | — | — | 9.7 | 28 |

| Blue Water Zone | 49 | 2004–06 | −64 | −60 | −63 | −53 | 260 | 259 | — | — | — | 7.1 | 29 |

| BULA/CMORE | 9 | 2007 | −16 | 17 | −170 | −159 | 45 | 45 | 48 | 278 | 50 | 5.5 | 30 |

| BV37+39 | 12 | 2007 | 20 | 34 | −66 | −64 | 46 | 46 | 181 | 448 | 60 | 7.1 | 12 |

| CARIACO | 156 | 1995–2010 | 11 | 11 | −65 | −65 | 2893 | 2885 | — | — | — | 7.4 | 31 |

| CCU LTER process | 68 | 2006–08 | 32 | 35 | −124 | −120 | 798 | 798 | — | — | — | 6.1 | 32 |

| CCU LTER survey | 818 | 2004–09 | 30 | 74 | −124 | −117 | 4406 | 4406 | — | — | — | 6.4 | 32 |

| Copin-Montegut | 10 | 1974 | −56 | −26 | 61 | 75 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 80 | 13 | 6.2 | 33 |

| Copin-Montegut | 1 | 1975 | 42 | 42 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 121 | 19 | 6.3 | 25 |

| CYCLOPS | 66 | 1971–72 | −35 | 56 | −18 | 142 | 66 | 66 | — | — | — | 9.4 | 34 |

| DCM | 17 | 1996 | 7 | 34 | −54 | −23 | 119 | 113 | — | — | — | 14 | 35 |

| DIAPAZON | 62 | 2002–03 | −24 | −20 | 166 | 168 | 202 | 203 | 305 | 238 | 27 | 8.8 | 36 |

| EDT1 2004 | 17 | 2004 | 30 | 31 | −66 | −64 | 259 | 259 | — | — | — | 6.8 | 37 |

| EDT2 2004 | 8 | 2004 | 30 | 32 | −66 | −64 | 244 | 244 | — | — | — | 6.8 | 37 |

| EDT3 2005 | 12 | 2005 | 30 | 32 | −67 | −64 | 231 | 231 | — | — | — | 5.4 | 37 |

| EDT4 2005 | 15 | 2005 | 30 | 30 | −69 | −68 | 224 | 224 | — | — | — | 5.5 | 37 |

| EUMELI | 18 | 1991–92 | 18 | 21 | −31 | −21 | — | 318 | 327 | — | 18 | — | 38 |

| FLUPAC | 42 | 1994 | −14 | 6 | −179 | −149 | 374 | 375 | 400 | 132 | 16 | 8.2 | 39 |

| FRUELA 95 | 35 | 1995–96 | −65 | −63 | −66 | −59 | 306 | 306 | — | — | — | 6.1 | 40 |

| Gulf of St Lawrence | 36 | 1992–94 | 43 | 50 | −66 | −60 | 397 | 398 | — | — | — | 6.1 | 24 |

| HOT | 195 | 1989–2009 | 23 | 23 | −158 | −158 | 1632 | 1632 | 1581 | 161 | 25 | 6.5 | 41 |

| IronEx II | 11 | 1995 | −7 | −4 | −111 | −105 | 114 | 114 | — | — | — | 5.9 | 42 |

| JGOFS Arabian Sea | 120 | 1995 | 10 | 24 | 57 | 69 | 1229 | 1217 | — | — | — | 4.9 | 43 |

| JGOFS EqPac | 99 | 1992 | −12 | 12 | −141 | −135 | 803 | 1468 | — | — | — | 7.3 | 44 |

| JGOFS S. Ocean | 175 | 1996–98 | −78 | −53 | −178 | 180 | 2150 | 2135 | — | — | — | 8.8 | 45 |

| Kahler | 10 | 2002 | 18 | 32 | −30 | −30 | 59 | 59 | 60 | 152 | 22 | 7.0 | 46 |

| Keycop | 12 | 1999–2000 | 39 | 40 | 25 | 26 | 70 | 59 | — | — | — | 1.1 | 47 |

| Latitud-II | 11 | 1995 | −33 | 25 | −45 | −18 | 16 | 16 | — | — | — | 12.3 | 48 |

| Line P | 100 | 1992–97 | 49 | 50 | −145 | −127 | 997 | 970 | — | — | — | 6.8 | 49 |

| Loh and Bauer | 4 | 1996 | −54 | 36 | −176 | −122 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 255 | 34 | 7.5 | 50 |

| MD03/ICHTYO | 123 | 1974 | −56 | −24 | 26 | 78 | 159 | 159 | 159 | 93 | 15 | 6.4 | 33 |

| MEDAR | 97 | 1991 −2001 | 41 | 45 | 5 | 14 | 1256 | 1160 | 190 | 165 | 21 | 8.1 | 51 |

| Meteor 36–2 | 32 | 1996 | 33 | 60 | −22 | −20 | 96 | 96 | — | — | — | 5.9 | 52 |

| Meteor 36–6 | 8 | 1996 | 46 | 48 | −20 | −18 | 73 | 73 | — | — | — | 6.9 | 53 |

| MOOGLI | 10 | 1997–99 | 43 | 43 | 5 | 5 | 114 | 121 | 123 | 182 | 22 | 8.1 | 54 |

| NABE | 20 | 1989 | 18 | 34 | −31 | −21 | 237 | 236 | 239 | 72 | 11 | 6.6 | 55 |

| NOPACCS | 110 | 1992–95 | −36 | 48 | 143 | 175 | 1405 | 1405 | — | — | — | 7.0 | 56 |

| OLIPAC | 13 | 1994 | −16 | 1 | −150 | −150 | — | 152 | 152 | — | 20 | — | 57 |

| OMEX | 228 | 1993–95 | 47 | 50 | −16 | −7 | 2216 | 1261 | 735 | 294 | 25 | 9.7 | 58 |

| OPEREX | 8 | 2008 | 22 | 26 | −160 | −157 | 58 | 58 | — | — | — | 6.1 | 59 |

| PALLTER Seasonal | 650 | 1991–2010 | −65 | −64 | −65 | −64 | 5775 | 5743 | — | — | — | 7.2 | 60 |

| PALLTER Survey | 679 | 1991–2010 | −70 | −79 | 7278 | 7232 | — | — | — | 6.6 | 60 | ||

| PROSOPE | 22 | 1999 | 31 | 43 | −10 | 22 | 217 | 221 | 223 | 115 | 16 | 7.1 | 61 |

| SBC LTER | 307 | 2000–10 | 34 | 35 | −121 | −119 | 4594 | 4593 | — | — | — | 6.3 | 62 |

| SEED | 12 | 2001 | 49 | 49 | 164 | 165 | 129 | 129 | 57 | 140 | 17 | 8.4 | 63 |

| SOIREE | 13 | 1999 | −61 | −61 | 140 | 141 | 102 | 102 | — | — | — | 5.9 | 64 |

| SUPER-HI-CAT | 13 | 2008 | 28 | 35 | −155 | −138 | 83 | 83 | 81 | 250 | 35 | 7.2 | 65 |

| Tuamotu | 15 | 1985–96 | −18 | −15 | −148 | −141 | 16 | 16 | 14 | 158 | 21 | 7.6 | 66 |

| WCSI | 18 | 2007–08 | 16 | 74 | 68 | 68 | — | — | — | 5.9 | 67 | ||

| X0705 | 29 | 2007 | 27 | 38 | −66 | −56 | 215 | 213 | 238 | 161 | 29 | 5.6 | 12 |

| X0804 | 34 | 2008 | 20 | 32 | −66 | −45 | 1256 | 1160 | 190 | 107 | 24 | 4.5 | 12 |

*Geometric means of elemental molar ratios.

It is worth noting that this represents an aggregated dataset collected by many independent researchers (Table 1 (availale online only)). Even though most studies utilize the same techniques and sample volumes, there are likely many small deviations in the technical approach. As a result, some care should be taken when comparing values.

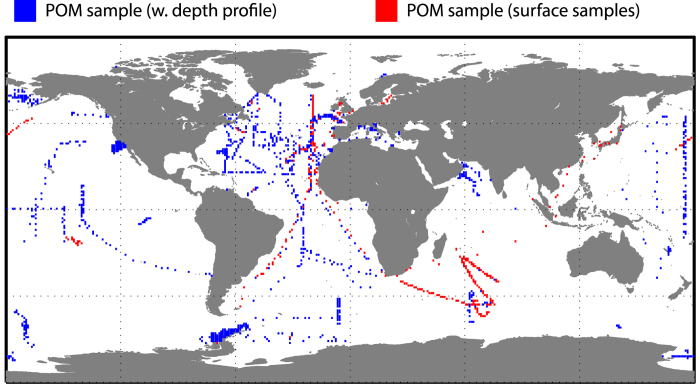

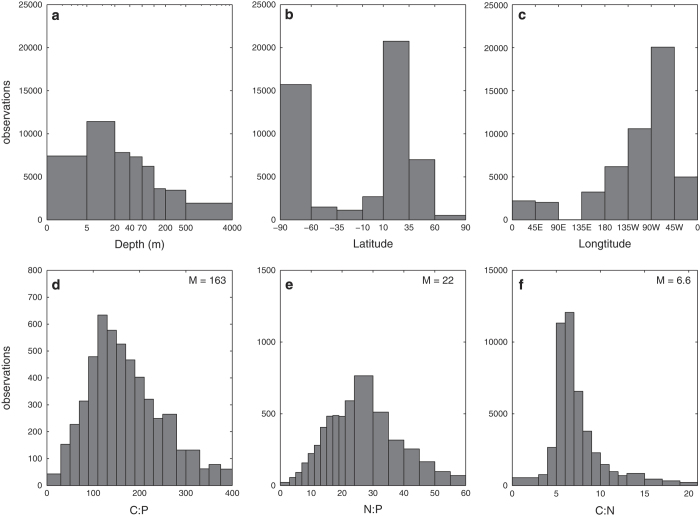

The data covers 5336 unique stations from all major ocean regions (Figure 1). 89% of the samples originate from the top 200 m of the water and thus the dataset is skewed towards processes occurring in or near the euphotic zone (Figure 2a). The data is also biased towards regions of oceanographic research. This includes samples near the Palmer Station in the Southern Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and Eastern North Pacific Ocean (including the HOT site and California Current) (Figure 2b and Figure 2c). Thus, this compilation of data identifies regions where we currently have very sparse data (e.g., the South Pacific, South Atlantic, and Eastern Indian Ocean). Overall, the median C:P, N:P, and C:N ratios are 163, 22, and 6.6, respectively, in this dataset but the data span a wide range for all three ratios (Figure 2d–f). Combined with the wide geographic extent of the data, this compilation will enable a range of analyses of elemental concentrations or ratios in particulate organic matter.

Figure 1. Global distribution of POM measurements in the dataset.

A depth profile was defined as at least two unique depths from the same station.

Figure 2. Summary of POM measurements and ratios in the aggregated dataset.

Histogram of the number of observations across depths (a), latitude (b), and longitude (c) as well as the range of C:P (d), N:P (e), and C:N (f) elemental ratios. M represents the median value. Please note a difference in the total number of observations for each elemental ratio.

Methods

Nearly all POC and PON measurements were done by collecting seawater particles onto glass-fibers filters (i.e., GF/F) and quantified using an combustion GC-IR based elemental analyzer68. The only exceptions were ‘EUMELI’ and ‘OLIPAC’, where PON was measured using a chemical oxidation technique38. Particulate phosphorus was quantified using the ash-hydrolysis method26,69. We operationally defined station IDs as samples taken within a 1°×1° area on the same day11.

The data was gathered by searching available databases (i.e., PANGAEA, BCO-DMO, JGOFS, and IFREMER) as well as published literature. We aggregated all available datasets in order to create the most exhaustive global description of particulate organic nutrients and thus did not exclude any specific cruises or time-series. The only data excluded were samples subjected to a prior manipulation or incubation.

Data Records

The dataset includes the following fields for each record:

Cruise

Year

Month

Day

Latitude (−90 to 90)

Longitude (−180 to 180)

Sampling depth (m)

Particulate organic Carbon (μM)

Particulate organic Nitrogen (μM)

Particulate organic Phosphorus (μM)

Data Record 1

The database files (June 20, 2014 version) in csv format were uploaded to Dryad (Data Citation 1). A file containing all the fields listed above is available. ‘−9999’ denotes missing data.

Data Record 2

The particulate nutrient data were also uploaded to the Biological and Chemical Oceanography Data Management Office system (BCO-DMO) (Data Citation 2) with all the fields listed above. The database is organized at level 0 by cruise dataset (Table 1 (availale online only)), level 1 by stations, and level 2 with the POM data. ‘−9999’ describes missing data. This dataset will be updated if new data becomes available.

Technical Validation

In our experience, when all precautions are taken, variance between replicate samples for elemental analysis can be <5%, assuming the actual sample is above the analytical blank. However, not all precautions are always taken, for example it is rare that when sampling for POC that the entire Niskin bottle is drained, well mixed and then subsampled. It is known that as the sample sits in the bottle, large particles sink to the bottom and often below the spigot resulting in an underestimation of particulate matter concentrations in the seawater sample70. There is also the question of limit of detection. For particulate analyses, this depends in part upon the volume you are filtering, the concentration of your analyte of interest and overall cleanliness of your procedures71. For example, in the Sargasso Sea, where particulate nutrients are very low, we filter 4 liters of seawater for particulate organic phosphorus26 to ensure that the sample well exceeds the blank. In our experience making these measurements using the methods reported here, reasonable blank measurements for POC, PON and POP are ~0.5 μM, ~0.04 μM and ~3 nM, respectively. It is common practice to subtract blanks from analyzed samples, and we assume that has been done for all reported data however, we cannot be fully confident in how that blank correction was conducted. Whether blank-corrected samples are significantly different than zero is a different question and depends upon the actual value and variability of the blank which is not commonly reported in published works or available datasets. However, we are confident that blank-corrected particulate organic matter concentrations greater than ~0.5 μM POC, ~0.05 μM PON and 5 nM POP are valid numbers to report. This benchmark may change between ocean regimes and with specific protocols. We should also note that some samples give either very high or low elemental ratios. These could arise from analytical artifacts, for example, one or both values in the ratio being close to the analytical detection limit, as well as other sampling artifacts. However, we currently do not have a good handle on the spatio-temporal variation in particulate nutrient concentrations and ratios and thus, it is difficult to give precise guidelines for flagging possible artifacts and thus really high/low values should be examined more closely and used with caution.

Usage Notes

The dataset can be used to identify novel regional or environmentally driven patterns in both the concentration of particulate organic matter as well as the ratios of different elements. Within this dataset are observations from time-series stations and thus temporal analysis of particulate organic matter concentrations and ratios can also be evaluated. Further, the data can be utilized to evaluate outputs from ocean biogeochemical models.

Additional information

Table 1 is only available in online version of this paper.

How to cite this article: Martiny, A. C. et al. Concentrations and ratios of particulate organic carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus in the global ocean. Sci. Data 1:140048 doi: 10.1038/sdata.2014.48 (2014).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the researchers for sharing their data with us and making this compilation possible as well as Cyndy Chandler and Steve Gegg for enabling the posting of the data at The Biological and Chemical Oceanography Data Management Office (BCO-DMO). We would like to acknowledge the NSF Dimensions of Biodiversity and Biological Oceanography programs (A.C.M. and M.W.L.) and the UCI Environment Institute (A.C.M. and J.A.V.) for supporting our research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Data Citations

- Martiny A. C., Vrugt J. A., Lomas M. W. 2014. Dryad. http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.d702p [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Martiny A. C., Vrugt J. A., Lomas M. W. 2014. The Biological and Chemical Oceanography Data Management Office. http://www.bco-dmo.org/dataset/526747

References

- Redfield A. C. On The Proportions Of Organic Derivatives In Sea Water And Their Relation To The Composition Of Plankton. James Johnstone Memorial Volume, 176–192 (Liverpool University Press, 1934). [Google Scholar]

- Redfield A. C. The biological control of the chemical factors in the environment. Am. Sci. 46, 1–18 (1958). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geider R. J. & La Roche J. Redfield revisited: variability of C : N : P in marine microalgae and its biochemical basis. Eur. J. Phycol. 37, 1–17 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Klausmeier C. A., Litchman E., Daufresne T. & Levin S. A. Optimal nitrogen-to-phosphorus stoichiometry of phytoplankton. Nature 429, 171–174 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman A. E., Allison S. D. & Martiny A. C. Phylogenetic constraints on elemental stoichiometry and resource allocation in heterotrophic marine bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 16, 1398–1410 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertilsson S., Berglund O., Karl D. M. & Chisholm S. W. Elemental composition of marine Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus: Implications for the ecological stoichiometry of the sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 48, 1721–1731 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Rhee G.-Y. A continuous culture study of phosphate uptake, growth rate and polyphosphate in Scenedesmus sp. J. Phycol. 9, 495–506 (1973). [Google Scholar]

- Broecker W. S. & Henderson G. M. The sequence of events surrounding Termination II and their implications for the cause of glacial-interglacial CO2 changes. Paleoceanography 13, 352–364 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Mills M. M. & Arrigo K. R. Magnitude of oceanic nitrogen fixation influenced by the nutrient uptake ratio of phytoplankton. Nat. Geosci. 3, 412–416 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Weber T. & Deutsch C. Oceanic nitrogen reservoir regulated by plankton diversity and ocean circulation. Nature 489, 419–422 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martiny A. C., Vrugt J. A., Primeau F. W. & Lomas M. W. Regional variation in the particulate organic carbon to nitrogen ratio in the surface ocean. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 27, 723–731 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Martiny A. C. et al. Strong latitudinal patterns in the elemental ratios of marine plankton and organic matter. Nat. Geosci. 6, 279–283 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Weber T. S. & Deutsch C. Ocean nutrient ratios governed by plankton biogeography. Nature 467, 550–554 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrigo K. R. et al. Phytoplankton community structure and the drawdown of nutrients and CO2 in the Southern Ocean. Science 283, 365–367 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daines S. J., Clark J. R. & Lenton T. M. Multiple environmental controls on phytoplankton growth strategies determine adaptive responses of the N: P ratio. Ecol. Lett. 17, 414–425 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonachela J. A., Allison S. D., Martiny A. C. & Levin S. A. A model for variable phytoplankton stoichiometry based on cell protein regulation. Biogeosciences 10, 4341–4356 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Geider R. J., MacIntyre H. L. & Kana T. M. A dynamic regulatory model of phytoplanktonic acclimation to light, nutrients, and temperature. Limnol. Oceanogr. 43, 679–694 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Aiken J. et al. The Atlantic Meridional Transect: overview and synthesis of data. Prog. Oceanogr. 45, 257–312 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Mahaffey C., Williams R. G., Wolff G. A. & Anderson W. T. Physical supply of nitrogen to phytoplankton in the Atlantic Ocean. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 18, GB1034 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Mengesha S., Dehairs F., Fiala M., Elskens M. & Goeyens L. Seasonal variation of phytoplankton community structure and nitrogen uptake regime in the Indian Sector of the Southern Ocean. Polar Biol. 20, 259–272 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc K. et al. Particulate biogenic silica and carbon production rates and particulate matter distribution in the Indian sector of the Subantarctic Ocean. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II 49, 3189–3206 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Smetacek V., DeBaar H. J. W., Bathmann U. V, Lochte K. & VanderLoeff M. M. R. Ecology and biogeochemistry of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current during austral spring: A summary of Southern Ocean JGOFS cruise ANT X/6 of RV Polarstern. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II 44, 1–21 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Provost C. in Berichte zur Polar- und Meeresforsch 68 (Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- Sathyendranath S. et al. Carbon-to-chlorophyll ratio and growth rate of phytoplankton in the sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 383, 73–84 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Copin-Montegut C. & Copin-Montegut G. Stoichiometry of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus in marine particulate matter. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. I 30, 31–46 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- Lomas M. W. et al. Sargasso Sea phosphorus biogeochemistry: an important role for dissolved organic phosphorus (DOP). Biogeosciences 7, 695–710 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Moutin T. et al. Phosphate availability and the ultimate control of new nitrogen input by nitrogen fixation in the tropical Pacific Ocean. Biogeosciences 5, 95–109 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Karl D. M. et al. Aerobic production of methane in the sea. Nat. Geosci. 1, 473–478 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Hopkinson B. M. et al. Iron limitation across chlorophyll gradients in the southern Drake Passage: Phytoplankton responses to iron addition and photosynthetic indicators of iron stress. Limnol. Oceanogr. 52, 2540–2554 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Hewson I., Paerl R. W., Tripp H. J., Zehr J. P. & Karl D. M. Metagenomic potential of microbial assemblages in the surface waters of the central Pacific Ocean tracks variability in oceanic habitat. Limnol. Oceanogr. 54, 1981–1994 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Karger F. et al. Annual cycle of primary production in the Cariaco Basin: Response to upwelling and implications for vertical export. J. Geophys. Res. 106, 4527–4542 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Ohman M. D., Powell J. R., Picheral M. & Jensen D. W. Mesozooplankton and particulate matter responses to a deep-water frontal system in the Southern California Current System. J. Plankton Res. 34, 815–827 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Copin-Montegut C. & Copin-Montegut G. Chemistry of particulate matter from South Indian and Antarctic Oceans. Deep. Res 25, 911–931 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- Krom M. D. et al. Summary and overview of the CYCLOPS P addition Lagrangian experiment in the Eastern Mediterranean. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II 52, 3090–3108 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis M. J. W. & Kraay G. W. Phytoplankton in the subtropical Atlantic Ocean: towards a better assessment of biomass and composition. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. I 51, 507–530 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Broeck N., Moutin T., Rodier M. & Le Bouteiller A. Seasonal variations of phosphate availability in the SW Pacific Ocean near New Caledonia. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 268, 1–12 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Buesseler K. O. et al. Particle fluxes associated with mesoscale eddies in the Sargasso Sea. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II 55, 1426–1444 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Pujopay M. & Raimbault P. Improvement of the wet-oxidation procedure for simultaneous determination of particulate organic nitrogen and phosphorus collected on filters. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 105, 203–207 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Rodier M. & Le Borgne R. Export flux of particles at the equator in the western and central Pacific ocean. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II 44, 2085–2113 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Bode A., Castro C. G., Doval M. D. & Varela M. New and regenerated production and ammonium regeneration in the western Bransfield Strait region (Antarctica) during phytoplankton bloom conditions in summer. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II 49, 787–804 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Karl D. M. et al. Ecological nitrogen-to-phosphorus stoichiometry at station ALOHA. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II 48, 1529–1566 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Coale K. H., Fitzwater S. E., Gordon R. M., Johnson K. S. & Barber R. T. Control of community growth and export production by upwelled iron in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Nature 379, 621–624 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Buesseler K. et al. Upper ocean export of particulate organic carbon in the Arabian Sea derived from thorium-234. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II 45, 2461–2487 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Buesseler K. O., Andrews J. A., Hartman M. C., Belastock R. & Chai F. Regional estimates of the export flux of particulate organic-carbon derived from Th-234 during the Jgofs Eqpac Program. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II 42, 777–804 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Cochran J. K. et al. Short-lived thorium isotopes (Th-234, Th-228) as indicators of POC export and particle cycling in the Ross Sea, Southern Ocean. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II 47, 3451–3490 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Dietze H., Oschlies A. & Kahler P. Internal-wave-induced and double-diffusive nutrient fluxes to the nutrient-consuming surface layer in the oligotrophic subtropical North Atlantic. Ocean Dyn. 54, 1–7 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Karageorgis A. P. et al. Comparison of particulate matter distribution, in relation to hydrography, in the mesotrophic Skagerrak and the oligotrophic northeastern Aegean Sea. Cont. Shelf Res. 23, 1787–1809 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Gasol J. M., Vazquez-Dominguez E., Vaque D., Agusti S. & Duarte C. M. Bacterial activity and diffusive nutrient supply in the oligotrophic Central Atlantic Ocean. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 56, 1–12 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Harrison P. J. Station papa time series: Insights into ecosystem dynamics. J. Oceanogr. 58, 259–264 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Loh A. N. & Bauer J. E. Distribution, partitioning and fluxes of dissolved and particulate organic C, N and P in the eastern North Pacific and Southern Oceans. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. I 47, 2287–2316 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Fichaut M. et al. MEDAR/MEDATLAS 2002: A Mediterranean and Black Sea database for operational oceanography. Elsevier Oceanogr. Ser 69, 645–648 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Kortzinger A., Koeve W., Kahler P. & Mintrop L. C : N ratios in the mixed layer during the productive season in the northeast Atlantic Ocean. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. I 48, 661–688 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Mienert J. et al. Nordatlantik 1996, Cruise No. 36, 6 June 1996—4 November 1996 (ed. Mienert, J.) 98 (METEOR-Berichte, 1998). [Google Scholar]

- De Madron X. D. et al. Nutrients and carbon budgets for the Gulf of Lion during the Moogli cruises. Oceanol. Acta 26, 421–433 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Passow U. & Peinert R. The role of plankton in particle-flux—2 case-studies from the Northeast Atlantic. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II 40, 573–585 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Tsubota H., Ishizaka J., Nishimura A. & Watanabe Y. W. Overview of NOPACCS (Northwest Pacific Carbon Cycle Study). J. Oceanogr. 55, 645–653 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Claustre H. et al. Variability in particle attenuation and chlorophyll fluorescence in the tropical Pacific: Scales, patterns, and biogeochemical implications. J. Geophys. Res. 104, 3401–3422 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Bode A. et al. Planktonic carbon and nitrogen cycling off northwest Spain: variations in production of particulate and dissolved organic pools. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 37, 95–107 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Guidi L. et al. Does eddy-eddy interaction control surface phytoplankton distribution and carbon export in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre? J. Geophys. Res. 117 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Karl D. M., Christian J. R., Dore J. E. & Letelier R. M. in Foundations for Ecological Research West of the Antarctic Peninsula 70 (American Geophysical Union, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- Van Wambeke F., Christaki U., Giannokourou A., Moutin T. & Souvemerzoglou K. Longitudinal and vertical trends of bacterial limitation by phosphorus and carbon in the Mediterranean Sea. Microb. Ecol. 43, 119–133 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halewood E. R., Carlson C. A., Brzezinski M. A., Reed D. C. & Goodman J. Annual cycle of organic matter partitioning and its availability to bacteria across the Santa Barbara Channel continental shelf. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 67, 189–209 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura T. et al. Dynamics and elemental stoichiometry of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus in particulate and dissolved organic pools during a phytoplankton bloom induced by in situ iron enrichment in the western subarctic Pacific (SEEDS-II). Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II 56, 2863–2874 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Buesseler K. O., Andrews J. E., Pike S. M. & Charette M. A. The effects of iron fertilization on carbon sequestration in the Southern Ocean. Science 304, 414–417 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente T. M. et al. SUPER HI-CAT: Survey of Underwater Plastic and Ecosystem Response between Hawaii and California. Proc. from 2010 AGU Ocean Sci. Meet (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Charpy L., Dufour P. & Garcia N. Particulate organic matter in sixteen Tuamotu atoll lagoons (French Polynesia). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 151, 55–65 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Maya M. V. et al. Intra-annual variability of carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes in suspended organic matter in waters of the western continental shelf of India. Biogeosciences 8, 3441–3456 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Sharp J. H. Improved analysis for “particulate” organic carbon and nitrogen from seawater. Limnol. Oceanogr. 19, 984–989 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- Solorzano L. & Sharp J. H. Determination of total dissolved phosphorus and particulate phosphorus in natural-waters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 25, 754–757 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen K., Orcutt K. M., Purdie D. A., Michaels A. F. & Knap A. H. Particulate organic carbon mass distribution at the Bermuda Atlantic Time-series Study (BATS) site. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II 48, 1697–1718 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Moran S. B., Charette M. A., Pike S. M. & Wicklund C. A. Differences in seawater particulate organic carbon concentration in samples collected using small- and large-volume methods: the importance of DOC adsorption to the filter blank. Mar. Chem. 67, 33–42 (1999). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Martiny A. C., Vrugt J. A., Lomas M. W. 2014. Dryad. http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.d702p [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Martiny A. C., Vrugt J. A., Lomas M. W. 2014. The Biological and Chemical Oceanography Data Management Office. http://www.bco-dmo.org/dataset/526747