Abstract

Efforts to identify meaningful functional imaging-based biomarkers are limited by the ability to reliably characterize inter-individual differences in human brain function. Although a growing number of connectomics-based measures are reported to have moderate to high test-retest reliability, the variability in data acquisition, experimental designs, and analytic methods precludes the ability to generalize results. The Consortium for Reliability and Reproducibility (CoRR) is working to address this challenge and establish test-retest reliability as a minimum standard for methods development in functional connectomics. Specifically, CoRR has aggregated 1,629 typical individuals’ resting state fMRI (rfMRI) data (5,093 rfMRI scans) from 18 international sites, and is openly sharing them via the International Data-sharing Neuroimaging Initiative (INDI). To allow researchers to generate various estimates of reliability and reproducibility, a variety of data acquisition procedures and experimental designs are included. Similarly, to enable users to assess the impact of commonly encountered artifacts (for example, motion) on characterizations of inter-individual variation, datasets of varying quality are included.

Background & Summary

Functional connectomics is a rapidly expanding area of human brain mapping1–4. Focused on the study of functional interactions among nodes in brain networks, functional connectomics is emerging as a mainstream tool to delineate variations in brain architecture among both individuals and populations5–8. Findings that established network features and well-known patterns of brain activity elicited via task performance are recapitulated in spontaneous brain activity patterns captured by resting-state fMRI (rfMRI)3–6,9–12, have been critical to the wide-spread acceptance of functional connectomics applications.

A growing literature has highlighted the possibility that functional network properties may explain individual differences in behavior and cognition4,7,8—the potential utility of which is supported by studies that suggest reliability for commonly used rfMRI measures13. Unfortunately, the field lacks a data platform by which researchers can rigorously explore the reliability of the many indices that continue to emerge. Such a platform is crucial for the refinement and evaluation of novel methods, as well as those that have gained widespread usage without sufficient consideration of reliability. Equally important is the notion that quantifying the reliability and reproducibility of the myriad connectomics-based measures can inform expectations regarding the potential of such approaches for biomarker identification13–16.

To address these challenges, the Consortium for Reliability and Reproducibility (CoRR) has aggregated previously collected test-retest imaging datasets from more than 36 laboratories around the world and shared them via the 1000 Functional Connectomes Project (FCP)5,17 and its International Neuroimaging Data-sharing Initiative (INDI)18. Although primarily focused on rfMRI, this initiative has worked to promote the sharing of diffusion imaging data as well. It is our hope that among its many possible uses, the CoRR repository will facilitate the: (1) Establishment of test-retest reliability and reproducibility for commonly used MR-based connectome metrics, (2) Determination of the range of variation in the reliability and reproducibility of these metrics across imaging sites and retest study designs, (3) Creation of a standard/benchmark test-retest dataset for the evaluation of novel metrics.

Here, we provide an overview of all the datasets currently aggregated by CoRR, and describe the standardized metadata and technical validation associated with these datasets, thereby facilitating immediate access to these data by the wider scientific community. Additional datasets, and richer descriptions of some of the studies producing these datasets, will be published separately (for example, A high resolution 7-Tesla rfMRI test-retest dataset with cognitive and physiological measures19). A list of all papers describing these individual studies will be maintained and periodically updated at the CoRR website (http://fcon_1000.projects.nitrc.org/indi/CoRR/html/data_citation.html).

Methods

Experimental design

At the time of submission, CoRR has received 40 distinct test-retest datasets that were independently collected by 36 imaging groups at 18 institutions. All CoRR contributions were based on studies approved by a local ethics committee; each contributor’s respective ethics committee approved submission of de-identified data. Data were fully deidentified by removing all 18 HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability)-protected health information identifiers, and face information from structural images prior to contribution. All data distributed were visually inspected before release. While all samples include at least one baseline scan and one retest scan, the specific designs and target populations employed across samples vary given the aggregation strategy used to build the resource. Since many individual (uniformly collected) datasets have reasonably large sample sizes allowing stable test-retest estimates, this variability across datasets provides an opportunity to generalize reliability estimates across scanning platforms, acquisition approaches, and target populations. The range of designs included is captured by the following classifications:

Within-Session Repeat.

o Scan repeated on same day

o Behavioral condition may or may not vary across scans depending on sample

Between-Session Repeat.

o Scan repeated one or more days later

o In most cases less than one week

Between-Session Repeat (Serial).

o Scan is repeated for 3 or more sessions in a short time-frame that is believed to be developmentally stable

Between-Session Repeat (Longitudinal developmental).

o Scan repeated at a distant time-point not believed to be developmentally equivalent. There is no exact definition of the minimum time for detecting developmental effects across scans, though designs typically span at least 3–6 months

Hybrid Design.

o Scans repeated one or more times on same day, as well as across one or more sessions

Table 1 presents an overview of the specific samples included in CoRR (Data Citations 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, , 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31). The vast majority included a single retest scan (48% within-session, 52% between-session). Three samples employed serial scanning designs, and one sample had a longitudinal developmental component. Most samples included presumed neurotypical adults; exceptions include the pediatric samples from Institute of Psychology at Chinese Academy of Sciences (IPCAS 2/7), University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine (UPSM) and New York University (NYU) and the lifespan samples from Nathan Kline Institute (NKI 1).

Table 1. CoRR sites and experimental design.

| Site | N | Age Range (Mean) | % Female | Retest Period | DOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Within Session—Single Retest

| |||||

| IPCAS (Liu)—Frames of Reference [IPCAS 4] | 20 | 21–28 (23.1) | 50 | 44 min | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.ipcas4 |

| IPCAS (Zuo)—Intrasession [IPCAS 7] | 74 | 6–17 (11.6) | 57 | 8 min | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.ipcas7 |

| NYU (Castellanos) [NYU 1] | 49 | 19.1–48 (30.3) | 47 | 60 min | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.nyu1 |

| Southwest (Chen)—Stroop [SWU 3] | 24 | 18–25 (20.4) | 34 | 90 min | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.swu3 |

| Southwest (Chen)—Emotion [SWU 2] | 27 | 18–24 (20.9) | 33 | 32 min | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.swu2 |

| Site | N | Age Range (Mean) | % Female | # Retests (Mean) | Retest Period Range (Mean Interval) | DOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Within Session—Multiple Retest

| ||||||

| Beijing Normal (Zang) [BNU 3] | 48 | 18–30 (22.5) | 50 | 2 (2) | 0–8 min (4 min) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.bnu3 |

| Berlin (Margulies) [BMB 1] | 50 | 19.9–59.7 (30.8) | 52 | 1 or 3 (1.4) | 10–25 min (8.3 min) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.bmb1 |

| IPCAS (Wei) [IPCAS 5] | 22 | 18–19 (18.3) | 0 | 1 or 2 (1.5) | 10–40 min (30 min) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.ipcas5 |

| Site | N | Age Range (Mean) | % Female | Retest Period Range (Mean) | DOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Between Sessions—Single Retest

| |||||

| IACAS (Jiang) [IACAS 1] | 28 | 19–43 (26.4) | 55 | 20–343 Days (75.2 Days) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.iacas1 |

| Munich (Blautzik)—Yearly [LMU 3] | 25 | 59–88 (69.8) | 36 | 315–463 Days (399.6 Days) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.lmu3 |

| Beijing Normal (He) [BNU 1] | 57 | 19–30 (23) | 47 | 33–55 Days (40.9 Days) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.bnu1 |

| Beijing Normal (Liu) [BNU 2] | 61 | 19.3–23.3 (21.3) | 46 | 103–189 Days (160.5 Days) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.bnu2 |

| IPCAS (Zuo)—Tai Chi [IPCAS 8] | 13 | 50–62 (57.6) | 46 | 367–810 Days (516 Days) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.ipcas8 |

| Nanjing (Lu) [JHNU 1] | 30 | 20–40 (23.3) | 30 | 0–900 Days (202.6 Days) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.jhnu1 |

| Southwest (Qiu) [SWU 4] | 235 | 17–27 (20) | 49 | 121–653 Days (302.1 Days) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.swu4 |

| NKI (Milham) [NKI 1] | 24 | 19–60 (34.4) | 75 | 14 Days (14 Days) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.nki1 |

| IPCAS (Jiang) [IPCAS 2] | 35 | 11–15 (13.3) | 65 | 7–59 Days (33.6 Days) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.ipcas2 |

| MRN (Mayer, Calhoun) [MRN 1] | 54 | 10–53 (24.9) | 50 | 7–158 Days (109 Days) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.mrn1 |

| Site | N | Age Range (Mean) | % Female | # Retests (Mean) | Retest Period Range (Mean Interval) | DOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Between Sessions—Multiple Retest

| ||||||

| Hangzhou (Weng) [HNU 1] | 30 | 20–30 (24.4) | 50 | 9 (9) | 3–40 Days (3.65 Days) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.hnu1 |

| Pittsburgh (Luna) [UPSM 1] | 100 | 10.1–19.7 (15.1) | 48 | 1 or 2 (1.23) | 473–1,404 Days (521 Days) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.upsm1 |

| Munich (Blautzik)—Young Adult [LMU 1] | 27 | 20–29 (24.3) | 48 | 4 or 5 (4.7) | 120–600 min (120 min) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.lmu1 |

| Munich (Blautzik)—Aging [LMU 2] | 40 | 20–79 (50.8) | 45 | 3 (3) | 150–450 min (150 min) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.lmu2 |

| Xuanwu (Li, Lu) [XHCUMS 1] | 25 | 36–62 (52.05) | 36 | 4 (4) | 12–197 Days (77.6 Days) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.xhcums1 |

| Within + Between Sessions | Within | Between | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | N | Age Range (Mean) | % Female | # Retests (Mean) | Retest Period Range (Mean Interval) | Retest Period Range (Mean Interval) | DOI |

| IPCAS (Zuo)—3 Day [IPCAS 6] | 2 | 21 & 25 | 50 | 44 (44) | 10–22 min (11.3 min) | 83–3,298 min (210 min) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.ipcas6 |

| IBATRT (La Conte) [IBA TRT 1] | 36 | 19–48 (26.8) | 51 | 1 or 3 (1.4) | 10 min (10 min) | 51–183 Days (115.4 Days) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.ibatrt1 |

| IPCAS (Fu) [IPCAS 1] | 30 | 18–24 (20.9) | 30 | 3 (3) | 29 min (29 min) | 5–24 Days (13.9 Days) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.ipcas1 |

| IPCAS (Liu)—Conflict Adaptation [IPCAS 3] | 36 | 17–25 (21) | 34 | 1 or 3 (1.3) | 40 min (40 min) | 1-2 Days (1.4 Days) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.ipcas3 |

| NYU (Di Martino) [NYU 2] | 187 | 6.47–55.03 (20.2) | 38 | 1, 2, 3, or 5 (1.6) | 9–132 min (25.5 min) | 1–203 Days (85.9 Days) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.nyu2 |

| Utah (Anderson)—Longitudinal [Utah 1] | 26 | 8–39 (20.2) | 0 | 2 (2) | 0 min (0 min) | 733–1,187 Days (928.4 Days) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.utah1 |

| Southwest (Chen)—Attentional Blink [SWU 1] | 20 | 19–24 (21.5) | 30 | 5 (5) | 20 min (20 min) | 20–2,900 min (1,460 min) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.swu1 |

| Montreal (Bellec) [UM 1] | 80 | 55–84 (65.4) | 27 | 3 (3) | 1 min (1 min) | 74–194 Days (111.4 Days) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.um1 |

| Utah Single [Utah 2] | 1 | 39 | 0 | 100 (100) | 1 min (1 min) | 0–4 Days (1.75 Days) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.utah2 |

| Wisconsin (Birn) [UWM 1] | 25 | 21–32 (24.9) | 44 | 2 (2) | 30 min (30 min) | 56–314 Days (110.4 Days) | http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.uwm1 |

Data Records

Data privacy

Prior to contribution, each investigator confirmed that the data in their contribution was collected with the approval of their local ethical committee or institutional review board, and that sharing via CoRR was in accord with their policies. In accord with prior FCP/INDI policies, face information was removed from anatomical images (FullAnonymize.sh V1.0b; http://www.nitrc.org/frs/shownotes.php?release_id=1902) and Neuroimaging Informatics Technology Initiative (NIFTI) headers replaced prior to open sharing to minimize the risk of re-identification.

Distribution for use

CoRR data sets can be accessed through either the COllaborative Informatics and Neuroimaging Suite (COINS) Data Exchange (http://coins.mrn.org/dx)20, or the Neuroimaging Informatics Tools and Resources Clearinghouse (NITRC; http://fcon_1000.projects.nitrc.org/indi/CoRR/html/index.html). CoRR datasets at the NITRC site are stored in .tar files sorted by site, each containing the necessary imaging data and phenotypic information. The COINS Data Exchange offers an enhanced graphical query tool, which enables users to target and download files in accord with specific search criteria. For each sharing venue, a user login must be established prior to downloading files. There are several groups of samples which were not included in the data analysis as they were in the data contribution/upload, preparation or correction stage at the time of analysis: Intrinsic Brain Activity, Test-Retest Dataset (IBATRT), Dartmouth College (DC 1), IPCAS 4, Hangzhou Normal University (HNU 2), Fudan University (FU 1), FU 2, Chengdu Huaxi Hospital (CHH 1), Max Planck Institute (MPG 1)19, Brain Genomics Superstruct Project (GSP) and New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT 1) (see more details on these sites at the CoRR website). Table 1 provides a static representation of the samples included in CoRR at the time of submission.

Imaging data

Consistent with its popularity in the imaging community and prior usage in FCP/INDI efforts, the NIFTI file format was selected for storage of CoRR imaging datasets, independent of modalities such as rfMRI, structural MRI (sMRI) and dMRI. Tables 2, 3, 4 (available online only) provide descriptions of the MRI sequences used for the various modalities for each of the imaging data file types.

Table 2. Imaging parameters for sMRI scans in CoRR.

| Site | Manufacturer | Model | Headcoil | Field Strength | Sequence | Flip Angle [Deg] | Inversion Time (TI) [ms] | Echo Time (TE) [ms] | Repetition Time (TR) [ms] | Bandwidth per Voxel (Readout) [Hz] | Parallel Acquisition | Number of Slices | Orientation | Slice Phase Encoding Direction | Slice Acquisition Order | Slice Thickness [mm] | Slice Gap [mm] | Field of View [mm] | Acquisition Matrix | Slice In-Place Resolution [mm2] | Acquisition Time [min:sec] | Fat Suppression | Phase Partial Fourier | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing Normal University 3 (BNU 3) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 7 | 1,100 | 3.39 | 2,530 | 190 | Off | 128 | s | A-P | int+ | 1.33 | 0.6515 | 256 | 256×192 | 1.3×1.0 | 8:07 | None | Off | |

| Berlin Mind and Brain 1 (BMB 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 9 | 900 | 2.98 | 2,300 | 240 | Off | 176 | s | A-P | int+ | 1 | 0.5 | 256 | 256×256 | 1.0×1.0 | 9:50 | None | Off | |

| Hangzhou Normal University 1 (HNU 1) | GE | Discovery MR750 | 8 Chan | 3T | 3D SPGR | 8 | 450 | Min Full | 8.06 | 125 | A2 | 180 | s | A-P | int+ | 1 | 0 | 250 | 250×250 | 1.0×1.0 | 5:01 | None | Off | |

| Dartmouth College (DC 1) | Philips | N/A | 32 Chan | 3T | 3D T1-TFE | 8 | 900 | 3.7 | 2,375 | 191.4 | S2.5 | 220 | a | R-L | N/A | 1 | N/A | 240 | 240×187 | 1.0×1.0 | 3:06 | None | N/A | Reconstructed voxels at .94×.94 |

| Institute of Automation, Chinese Academy of Sciences 1 (IACAS 1) | GE | Signa HDx | 8 Chan | 3T | 3D BRAVO | 7 | 1,100 | 2.984 | 7.788 | 122 | A2 | 192 | s | R-L | seq+ | 1 | 0 | 256 | 256×256 | 1.0×1.0 | 5:02 | None | Off | |

| Intrinsic Brain Activity, Test-Retest Dataset (IBATRT) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 8 | 900 | 3.02 | 2,600 | 130 | G2 | 176 | s | A-P | seq+ | 1 | 0.5 | 256 | 256×256 | 1.0×1.0 | 4:38 | None | 6/8 | |

| Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences 1 (IPCAS 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | 8 Chan | 3T | MPRAGE | 7 | 1,100 | 2.51 | 2,530 | 170 | G2 | 128 | s | A-P | seq+ | 1.3 | 0.65 | 256 | 256×256 | 1.0×1.0 | 5:53 | None | Off | |

| Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences 2 (IPCAS 2) | Siemens | TrioTim | 32 Chan | 3T | MPRAGE | 9 | 900 | 2.95 | 2,300 | 130 | Off | 160 | s | A-P | seq+ | 1.2 | 0.6 | 240 | 240×226 | 0.9×0.9 | 9:14 | None | Off | |

| Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences 3 (IPCAS 3) | Siemens | TrioTim | 8 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 7 | 1,100 | 2.51 | 2,530 | 170 | Off | 128 | s | A-P | int+ | 1.33 | 256 | 256×256 | 1.0×1.0 | 5:24 | None | Off | ||

| Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences 4 (IPCAS 4) | GE | Discovery | 8 Chan | 3T | 3D SPGR | 8 | 450 | 3.136 | 8,068 | 31.25 | A2 | 250 | s | A-P | int+ | 1 | 0 | 250 | 250×250 | 1.0×1.0 | 5:01 | None | Off | |

| Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences 5 (IPCAS 5) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 7 | 1,100 | 3.5 | 2,530 | 190 | G2 | 176 | s | A-P | int+ | 1 | 0.5 | 256 | 256×256 | 1.0×1.0 | 6:03 | None | Off | |

| Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences 7 (IPCAS 7) | Siemens | TrioTim | 8 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 8 | 900 | 3.02 | 2,600 | 180 | Off | 176 | A-P | seq+ | 1 | 0.5 | 256 | 256×256 | 1.0×1.0 | 8:19 | None | 6/8 | ||

| Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences 8 (IPCAS 8) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 7 | 1,100 | 3.39 | 2,530 | 190 | Off | 128 | s | A-P | int+ | 1.3 | 0.65 | 256 | 256×192 | 1.3×1.0 | 8:07 | None | Off | |

| Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences 6 (IPCAS 6) | Siemens | TrioTim | 8 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 9 | 900 | 2.52 | 1,900 | 170 | Off | 176 | s | A-P | seq+ | 1 | 0.5 | 250 | 256×246 | 1.0×1.0 | 4:17 | None | Off | |

| University of Montreal 1 (UM 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 9 | 900 | 2.98 | 2,300 | 240 | G2 | 176 | s | A-P | int+ | 1 | 0.5 | 256 | 256×256 | 1.0×1.0 | 5:12 | None | Off | |

| Mind Research Network (MRN 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | 3D MEMPR | 7 | 1,200 | 1.64/3.5/5.36/7.22/9.08 | 2,530 | 651 | G2 | 192 | s oblique | A-P | int+ | 1 | 0.5 | 256 | 256×256 | 1.0×1.0 | 6:03 | None | Off | |

| Ludwig-Maximilians-University 2 (LMU 2) | Siemens | Verio | 12 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 9 | 900 | 3.06 | 2,400 | 230 | G2 | 160 | s | A-P | int+ | 1 | 0.5 | 256 | 256×246 | 1.0×1.0 | 4:45 | None | 7/8 | |

| Ludwig-Maximilians-University 1 (LMU 1) | Philips | Achieva | 32 Chan | 3T | 3D T1-TFE | 8 | 900 | N/A | 2,375 | 191.5 | S2/2.5 | 220 | a | R-L | seq+ | 1 | 0 | 240 | 240×187 | 1.0×1.0 | 3:06 | None | None | Reconstructed voxels at .94×.94 |

| Ludwig-Maximilians-University 3 (LMU 3) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 9 | 900 | 3.06 | 2,400 | 230 | G2 | 256 | s | A-P | int+ | 1 | 0.5 | 256 | 256×246 | 1.0×1.0 | 4:45 | None | 7/8 | |

| Jinling Hospital, Nanjing University 1 (JHNU 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | 8 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 9 | 900 | 2.98 | 2,300 | 240 | Off | 176 | s | A-P | seq+ | 1 | 0 | 256 | 256×256 | 1.0×1.0 | 9:50 | None | Off | |

| Nathan Kline Institute 1 (NKI 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | 32 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 9 | 900 | 2.52 | 1,900 | 170 | G2 | 176 | s | A-P | seq+ | 1 | 0.5 | 250 | 256×246 | 1.0×1.0 | 4:18 | None | Off | |

| New York University 2 (NYU 2) | Siemens | Allegra | 1 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 7 | 1,100 | 3.25 | 2,530 | 200 | Off | 128 | s | A-P | seq+ | 1.3 | 0.65 | 256 | 256×192 | 1.3×1.0 | 8:07 | None | Off | |

| New York University 1 (NYU 1) | Siemens | Allegra | 1 Chan | 3T | MPRAGE | 8 | 900 | 3.93 | 2,500 | N/A | N/A | 176 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | 256 | 256×256 | 1.0×1.0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine (UPSM) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 8 | 1,050 | 3.43 | 2,100 | 240 | G2 | 192 | a oblique | R-L | int+ | 1 | 0.5 | 256 | 256×256 | 1.0×1.0 | 3:59 | None | Off | |

| Southwest University 1 (SWU 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | 8 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 9 | 900 | 2.52 | 1,900 | 170 | G2 | 176 | s | A-P | seq+ | 1 | 0.5 | 250 | 256×246 | 1.0×1.0 | 4:18 | None | Off | |

| Southwest University 3 (SWU 3) | Siemens | TrioTim | 8 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 9 | 900 | 2.52 | 1,900 | 170 | G2 | 176 | s | A-P | seq+ | 1 | 0.5 | 250 | 256×246 | 1.0×1.0 | 4:18 | None | Off | |

| Southwest University 2 (SWU 2) | Siemens | TrioTim | 8 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 9 | 900 | 2.52 | 1,900 | 170 | G2 | 176 | s | A-P | seq+ | 1 | 0.5 | 250 | 256×246 | 1.0×1.0 | 4:18 | None | Off | |

| Southwest University 4 (SWU 4) | Siemens | TrioTim | 8 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 9 | 900 | 2.52 | 1,900 | 170 | G2 | 176 | s | A-P | seq+ | 1 | 0.5 | 256 | 256×256 | 1.0×1.0 | 4:26 | None | Off | |

| Beijing Normal University 1 (BNU 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 7 | 1,100 | 3.39 | 2,530 | 256 | Off | 144 | s | A-P | int+ | 1.3 | 0.65 | 256 | 256×192 | 1.3×1.0 | 8:07 | None | Off | |

| Beijing Normal University 2 (BNU 2) (Test) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 7 | 1,100 | 3.39 | 2,530 | 256 | Off | 128 | s | A-P | int+ | 1.3 | 0.65 | 256 | 256×192 | 1.3×1.0 | 8:07 | None | Off | |

| Beijing Normal University 2 (BNU 2) (Retest) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 7 | 1,100 | 3.45 | 2,530 | 256 | Off | 176 | s | A-P | int+ | 1 | 0.5 | 256 | 256×256 | 1.0×1.0 | 10:49 | None | Off | |

| University of Utah 1 (Utah 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 9 | 900 | 2.91 | 2,300 | 240 | Off | 160 | s | A-P | int+ | 1.2 | 0.6 | 256 | 256×256 | 1.0×1.0 | 9:14 | None | Off | |

| University of Utah 2 (Utah 2) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 9 | 900 | 2.91 | 2,300 | 240 | Off | 160 | s | A-P | int+ | 1.2 | 0.6 | 256 | 256×256 | 1.0×1.0 | 9:14 | None | Off | |

| University of Washington—Madison 1 (UWM 1) | GE | Discovery | 8 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 12 | 450 | 3.18 | 8.13 | 244 | Off | 160 | a | R-L | Simultaneous (3D) | 1 | 0 | 256 | 256×256 | 1.0×1.0 | 7:30 | None | Off | |

| Xuanwu Hospital, Capital University of Medical Sciences 1 (XHCUMS 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | 3D MPRAGE | 9 | 800 | 2.15 | 1,600 | 200 | Off | 176 | s oblique | A-P | seq+ | 1 | 0.5 | 256 | 256×256 | 1.0×1.0 | 5:09 | None | 6/8 |

Table 3. Imaging parameters for rfMRI scans in CoRR.

| Site | Manufacturer | Model | Headcoil | Field Strength | Sequence | Flip Angle [Deg] | Echo Time (TE) [ms] | Repetition Time (TR) [ms] | Bandwidth per Voxel (Readout) [Hz] | Parallel Acquisition | Number of Slices | Orientation | Slice Phase Encoding Direction | Slice Acquisition Order | Slice Thickness [mm] | Slice Gap [mm] | Field of View [mm] | Acquisition Matrix | Slice In-Place Resolution [mm2] | Number of Measurements | Acquisition Time [min:sec] | Fat Suppression | Prospective Motion Correction | Retrospective Motion Correction | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing Normal University 3 (BNU 3) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 2,000 | 2,520 | Off | 34 | a | A-P | int+ | 3.5 | 0.7 | 200 | 64×64 | 3.5×3.5 | 150 | 8:06 | Yes | No | No | |

| Berlin Mind and Brain 1 (BMB 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 2,300 | 2,232 | Off | 34 | a | A-P | int+ | 4 | 0 | 192 | 64×64 | 3.0×3.0 | 200 | 7:45 | Yes | No | No | |

| Hangzhou Normal University 1 (HNU 1) | GE | Discovery MR750 | 8 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 2,000 | 3437.5 | On | 43 | a | A-P | int+ | 3.4 | 0 | 220 | 64×64 | 3.4×3.4 | 300 | 10:00 | Yes | No | No | |

| Dartmouth College (DC 1) | Philips | N/A | 32 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 35 | 2,500 | 3,625 | S2 | 36 | a | A-P | N/A | 3.5 | 0.5 | 240 | 80×80 | 3.0×3.0 | 120 | 5:10 | Yes | No | N/A | |

| Institute of Automation, Chinese Academy of Sciences 1 (IACAS 1) | GE | Signa HDx | 8 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 2,000 | 7812.5 | Off | 32 | N/A | R-L | int+ | 4 | 0.6 | 220 | 64×64 | 3.4×3.4 | 240 | 8:00 | No | N/A | N/A | |

| Intrinsic Brain Activity, Test-Retest Dataset (IBATRT) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 1,750 | 2,442 | Off | 29 | a | A-P | seq+ | 3.6 | 0.36 | 220 | 64×64 | 3.4×3.4 | 343 | 10:04 | Yes | No | No | |

| Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences 1 (IPCAS 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | 8 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 2,000 | 2,232 | Off | 32 | a | A-P | int+ | 4 | 0.8 | 256 | 64×64 | 4.0×4.0 | 205 | 6:54 | Yes | No | N/A | |

| Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences 2 (IPCAS 2) | Siemens | TrioTim | 32 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 2,500 | 2,232 | Off | 32 | a | A-P | int+ | 3 | 0.99 | 240 | 64×64 | 3.8×3.8 | 212 | 8:57 | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences 3 (IPCAS 3) | Siemens | TrioTim | 8 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 2,000 | 2,232 | Off | 64 | a | A-P | int+ | 3 | 0.99 | 220 | 64×64 | 3.4×3.4 | 180 | 6:00 | Yes | No | No | |

| Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences 4 (IPCAS 4) | GE | Discovery MR750 | 8 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 2,000 | 250 | Off | 37 | a | A-P | int+ | 3.5 | 0 | 224 | 64×64 | 3.5×3.5 | 180 | 6:04 | Yes | No | No | |

| Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences 5 (IPCAS 5) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 2,000 | 2,298 | Off | 33 | c | F-H | int+ | 5 | 0 | 200 | 64×64 | 3.1×3.1 | 170 | 5:44 | Yes | No | No | |

| Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences 7 (IPCAS 7) | Siemens | TrioTim | 8 Chan | 3T | EPI | 80 | 30 | 2,500 | 2,240 | Off | 38 | a | A-P | int+ | 3 | 0.33 | 216 | 72×72 | 3.0×3.0 | 184 | 7:45 | Yes | No | No | |

| Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences 8 (IPCAS 8) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 2,000 | 2,520 | Off | 33 | a | A-P | int+ | 3 | 0.9 | 220 | 64×64 | 3.4×3.4 | 240 | 8:06 | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences 6 (IPCAS 6) | Siemens | TrioTim | 8 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 2,500 | 2,298 | Off | 25 | a | A-P | int+ | 3.5 | 3.5 | 224 | 64×64 | 3.5×3.5 | 242 | 10:05 | Yes | No | No | |

| University of Montreal 1 (UM 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 2,000 | 2,442 | Off | 32 | a | A-P | seq- | 4 | 0 | 256 | 64×64 | 4.0×4.0 | 150 | 5:04 | Yes | No | No | |

| Mind Research Network (MRN 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | EPI | 75 | 29 | 2,000 | 2,170 | Off | 33 | a oblique | A-P | int+ | 3.5 | 1.05 | 240 | 64×64 | 3.8×3.8 | 150 | 5:04 | Yes | No | No | |

| Ludwig-Maximilians-University 2 (LMU 2) | Siemens | Verio | 12 Chan | 3T | EPI | 80 | 30 | 3,000 | 2,232 | Off | 28 | a | A-P | int+ | 4 | 0.4 | 192 | 64×64 | 3.0×3.0 | 120 | 6:06 | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Ludwig-Maximilians-University 1 (LMU 1) | Philips | Achieva | 32 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 2,500 | 2,032 | S3 | 52 | a | A-P | seq+ | 3 | 0 | 224×233 | 76×79 | 2.95×2.95 | 180 | 7:35 | Yes | Yes | N/A | Data Reconstructed at 1.65×1.65 in plane resolution |

| Ludwig-Maximilians-University 3 (LMU 3) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | EPI | 80 | 30 | 3,000 | 2,232 | Off | 36 | a | A-P | int+ | 4 | 0.4 | 192 | 64×64 | 3.0×3.0 | 120 | 6:06 | Yes | No | No | |

| Jinling Hospital, Nanjing University 1 (JHNU 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | 8 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 2,000 | 2,230 | 2 | 30 | a | A-P | int+ | 4 | 0.4 | 240 | 64×64 | 3.75×3.75 | 250 | 8:20 | Yes | No | No | |

| Nathan Kline Institute 1 (NKI 1) (2500) | Siemens | TrioTim | 32 Chan | 3T | EPI | 80 | 30 | 2,500 | 2,240 | Off | 38 | a | A-P | int+ | 3 | 0.33 | 216 | 72×72 | 3.0×3.0 | 120 | 5:05 | Yes | No | No | |

| Nathan Kline Institute 1 (NKI 1) (1400) | Siemens | TrioTim | 32 Chan | 3T | EPI | 65 | 30 | 1,400 | 1,786 | Off | 64 | a | A-P | int+ | 2 | 0 | 224 | 112×112 | 2.0×2.0 | 404 | 9:35 | Yes | No | No | |

| Nathan Kline Institute 1 (NKI 1) (645) | Siemens | TrioTim | 32 Chan | 3T | EPI | 60 | 30 | 645 | 2,598 | Off | 40 | a | A-P | int+ | 3 | 0 | 222 | 74×74 | 3.0×3.0 | 900 | 9:46 | Yes | No | No | |

| New York University 2 (NYU 2) | Siemens | Allegra | 1 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 15 | 2,000 | 3,906 | Off | 33 | a oblique | R-L | int+ | 4 | 0 | 240 | 80×80 | 3.0×3.0 | 180 | 6:00 | Yes | No | N/A | |

| New York University 1 (NYU 1) | Siemens | Allegra | 1 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 25 | 2,000 | N/A | N/A | 39 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3 | N/A | 192 | 64×64 | 3.0×3.0 | 197 | 6:34 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine (UPSM) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | EPI | 70 | 29 | 1,500 | 2,694 | G2 | 29 | a oblique | P-A | seq+ | 4 | 0 | 200 | 64×64 | 3.1×3.1 | 200 | 5:06 | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Southwest University 1 (SWU 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | 8 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 2,000 | 2,232 | Off | 33 | a | A-P | int+ | 3 | 0.6 | 200 | 64×64 | 3.1×3.1 | 240 | 8:06 | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Southwest University 3 (SWU 3) | Siemens | TrioTim | 8 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 2,000 | 2,232 | Off | 32 | a oblique | A-P | int+ | 3 | 0.99 | 220 | 64×64 | 3.4×3.4 | 242 | 8:08 | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Southwest University 2 (SWU 2) | Siemens | TrioTim | 8 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 2,000 | 2,232 | Off | 32 | a oblique | A-P | int+ | 3 | 0.99 | 220 | 64×64 | 3.4×3.4 | 300 | 10:04 | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Southwest University 4 (SWU 4) | Siemens | TrioTim | 8 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 2,000 | 2,232 | Off | 32 | a | A-P | int+ | 3 | 1 | 220 | 64×64 | 3.4×3.4 | 242 | 8:06 | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Beijing Normal University 1 (BNU 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 2,000 | 2,520 | Off | 33 | a | A-P | int+ | 3.5 | 0.7 | 200 | 64×64 | 3.1×3.1 | 200 | 6:46 | Yes | No | No | |

| Beijing Normal University 2 (BNU 2) (Test) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 2,000 | 2,520 | Off | 33 | a | A-P | int+ | 3 | 0.6 | 200 | 64×64 | 3.1×3.1 | 240 | 8:06 | Yes | No | No | |

| Beijing Normal University 2 (BNU 2) (Retest) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 1,500 | 2,520 | Off | 25 | a | A-P | int+ | 4 | 0.8 | 200 | 64×64 | 3.1×3.1 | 420 | 10:36 | Yes | No | Yes | |

| University of Utah 1 (Utah 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 28 | 2,000 | 2,894 | Off | 40 | a | A-P | int+ | 3 | 0.3 | 220 | 64×64 | 3.4×3.4 | 240 | 8:06 | Yes | No | Yes | |

| University of Utah 2 (Utah 2) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 28 | 2,000 | 2,894 | Off | 40 | a | A-P | int+ | 3 | 0.3 | 220 | 64×64 | 3.4×3.4 | 240 | 8:06 | Yes | No | Yes | |

| University of Washington—Madison 1 (UWM 1) | GE | Discovery MR750 | 8 chan | 3T | EPI | 60 | 25 | 2,600 | N/A | Off | 40 | N/A | A-P | int+ | 3.5 | 0 | 224 | 64×64 | 3.5×3.5 | 231 | 10:01 | No (Spectral Spatial RF pulse) | N/A | N/A | |

| Xuanwu Hospital, Capital University of Medical Sciences 1 (XHCUMS 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | 12 Chan | 3T | EPI | 90 | 30 | 3,000 | 2,232 | Off | 43 | a oblique | A-P | int+ | 3 | 0.48 | 192 | 64×64 | 3.0×3.0 | 124 | 6:20 | Yes | No | N/A |

Table 4. Imaging parameters for dMRI scans in CoRR.

| Site | Manufacturer | Model | Sequence | Headcoil | Field Strength | Flip Angle [Deg] | Echo Time (TE) [ms] | Repetition Time (TR) [ms] | Bandwidth per Voxel (Readout) [Hz] | Parallel Acquisition | Number of Slices | Orientation | Slice Phase Encoding Direction | Slice Acquisition Order | Slice Thickness [mm] | Slice Gap [mm] | Field of View [mm] | Acquisition Matrix | Slice In-Place Resolution [mm 2 ] | Number of Measurements | Acquisition Time [min:sec] | Fat Suppression | Phase Partial Fourier | Number of Directions | Number of B Zeros | B Value(s) [s/mm 2 ] | Averages | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing Normal University 3 (BNU 3) | Siemens | TrioTim | EPI | 3T | N/A | 104 | 7,200 | 1,396 | G2 | 49 | a | A-P | int+ | 2.5 | 0 | 230 | 128×128 | 1.8×1.8 | 65 | 8:11 | Yes | None | 64 | 1 | 1,000 | 1 | ||

| Hangzhou Normal University 1 (HNU 1) | GE | Min | 8,600 | 68 | R-L | int+ | 1.5 | 0 | 192 | 128×128 | 1.5×1.5 | 33 | Yes | 30 | 1,000 | |||||||||||||

| Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IPCAS 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | 62 | 62 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IPCAS 2) | 39 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IPCAS 8) | Siemens | TrioTim | EPI | 3T | 104 | 6,600 | 1,396 | G2 | 45 | a | A-P | int+ | 3 | 0 | 230 | 128×128 | 1.8×1.8 | 65 | 7:30 | Yes | None | 64 | 1 | 1,000 | 1 | |||

| Mind Research Network 1 (MRN 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | EPI | 3T | N/A | 84 | 9,000 | 1,562 | G2 | 72 | a | A-P | int+ | 2 | 0 | 256 | 128×128 | 2.0×2.0 | 35 | 5:42 | Yes | 6/8 | 35 | 0 | 800 | 1 | ||

| Nathan Kline Institute 1 (NKI 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | EPI | 3T | 90 | 85 | 2,400 | 1,814 | Off | 64 | a | A-P | int+ | 2 | 0 | 212 | 106×106 | 2.0×2.0 | 137 | 5:58 | Yes | 6/8 | 137 | 0 | 1,500 | 1 | ||

| Southwest University 4 (SWU 4) | Siemens | TrioTim | 93 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Beijing Normal University 1 (BNU 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | EPI | 3T | 89 | 8,000 | 1,562 | G2 | 62 | a | A-P | int+ | 2.2 | 0 | 282 | 128×128 | 2.2×2.2 | 31 | 4:34 | Yes | 6/8 | 30 | 1 | 1,000 | 1 | |||

| Xuanwu Hospital, Capital University of Medical Sciences (XHCUMS 1) | Siemens | TrioTim | EPI | 3T | 83 | 8,000 | 1,396 | G2 | 64 | a | A-P | int+ | 2 | 0 | 256 | 128×128 | 2.0×2.0 | 65 | 9:06 | Yes | 6/8 | 64 | 1 | 700 | 1 |

Phenotypic information

All phenotypic data are stored in comma separated value (.csv) files. Basic information such as age and gender has been collected for each site to facilitate aggregation with minimal demographic variables. Table 5 (available online only) depicts the data legend provided to CoRR contributors.

Table 5. Phenotypic protocols in CoRR.

| CoRR Data Legend | COLUMN LABEL | DESCRIPTION | DATA TYPE | REQUIREMENT LEVEL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUBID | INDI Subject ID | integer | core | |

| AGE_AT_SCAN_1 | Age at scan session 1 in years (1 decimal place) | float | core | |

| SEX | sex (1: female, 2: male) | integer | core | |

| DSM_IV_TR | DSM-based Psychiatric Diagnosis (CPT Code) | integer | optional | |

| FIQ | Full-scale IQ | integer | optional | |

| VIQ | Verbal IQ | integer | optional | |

| PIQ | Peformance IQ | integer | optional | |

| BMI | Body Mass Index | float | optional | |

| RESTING STATE_INSTRUCTION | Instruction | string | core | |

| VISUAL_STIMULATION_CONDITION | Visual stimulation for rest (1: fixation, 2: blank screen, 3: word, 4: eyes closed, 5: other) | integer | core | |

| RETEST DESIGN | 1: Within Session, 2: Between Session, 3: Within + Between | integer | core | |

| baseline | PRECEDING_CONDITION | 0: No active task, 1: active task, 2: music listening, 3: video watching, 4: unknown | integer | core |

| TIME_OF_DAY | 0[0-5:59], 1[6:00-11:59], 2[12:00-17:59], 3[18:00-23:59] | integer | preferred | |

| SATIETY | 0: unknown, 1: post-prandial, 2: fasting | integer | preferred | |

| LMP | Number of days since start of last menstrual period (−1: male, 0: unknown) | integer | preferred | |

| retest 1 | RETEST DURATION | Time since baseline | real | core |

| RETEST_UNITS | m: min, d: days | string | core | |

| PRECEDING_CONDITION | 0: No active task, 1: active task, 2: music listening, 3: video watching, 4: unknown | integer | core | |

| TIME_OF_DAY | 0[0-5:59], 1[6:00-11:59], 2[12:00-17:59], 3[18:00-23:59] | integer | preferred | |

| SATIETY | 0: unknown, 1: post-prandial, 2: fasting | integer | preferred | |

| LMP | Number of days since start of last menstrual period (−1: male, 0: unknown) | integer | preferred | |

| retest 2 | RETEST DURATION | Time since baseline | real | core |

| RETEST_UNITS | m: min, d: days | string | core | |

| PRECEDING_CONDITION | 0: No active task, 1: active task, 2: music listening, 3: video watching, 4: unknown | integer | core | |

| TIME_OF_DAY | 0[0-5:59], 1[6:00-11:59], 2[12:00-17:59], 3[18:00-23:59] | integer | preferred | |

| SATIETY | 0: unknown, 1: post-prandial, 2: fasting | integer | preferred | |

| LMP | Number of days since start of last menstrual period (−1: male, 0: unknown) | integer | preferred | |

| retest 3 | RETEST DURATION | Time since baseline | real | core |

| RETEST_UNITS | m: min, d: days | string | core | |

| PRECEDING_CONDITION | 0: No active task, 1: active task, 2: music listening, 3: video watching, 4: unknown | integer | core | |

| TIME_OF_DAY | 0[0-5:59], 1[6:00-11:59], 2[12:00-17:59], 3[18:00-23:59] | integer | preferred | |

| SATIETY | 0: unknown, 1: post-prandial, 2: fasting | integer | preferred | |

| LMP | Number of days since start of last menstrual period (−1: male, 0: unknown) | integer | preferred | |

| retest 4 | RETEST DURATION | Time since baseline | real | core |

| RETEST_UNITS | m: min, d: days | string | core | |

| PRECEDING_CONDITION | 0: No active task, 1: active task, 2: music listening, 3: video watching, 4: unknown | integer | core | |

| TIME_OF_DAY | 0[0-5:59], 1[6:00-11:59], 2[12:00-17:59], 3[18:00-23:59] | integer | preferred | |

| SATIETY | 0: unknown, 1: post-prandial, 2: fasting | integer | preferred | |

| LMP | Number of days since start of last menstrual period (-1: male, 0: unknown) | integer | preferred | |

| retest 5 | RETEST DURATION | Time since baseline | real | core |

| RETEST_UNITS | m: min, d: days | string | core | |

| PRECEDING_CONDITION | 0: No active task, 1: active task, 2: music listening, 3: video watching, 4: unknown | integer | core | |

| TIME_OF_DAY | 0[0-5:59], 1[6:00-11:59], 2[12:00-17:59], 3[18:00-23:59] | integer | preferred | |

| SATIETY | 0: unknown, 1: post-prandial, 2: fasting | integer | preferred | |

| LMP | Number of days since start of last menstrual period (−1: male, 0: unknown) | integer | preferred | |

| retest 6 | RETEST DURATION | Time since baseline | real | core |

| RETEST_UNITS | m: min, d: days | string | core | |

| PRECEDING_CONDITION | 0: No active task, 1: active task, 2: music listening, 3: video watching, 4: unknown | integer | core | |

| TIME_OF_DAY | 0[0-5:59], 1[6:00-11:59], 2[12:00-17:59], 3[18:00-23:59] | integer | preferred | |

| SATIETY | 0: unknown, 1: post-prandial, 2: fasting | integer | preferred | |

| LMP | Number of days since start of last menstrual period (−1: male, 0: unknown) | integer | preferred | |

| retest 7 | RETEST DURATION | Time since baseline | real | core |

| RETEST_UNITS | m: min, d: days | string | core | |

| PRECEDING_CONDITION | 0: No active task, 1: active task, 2: music listening, 3: video watching, 4: unknown | integer | core | |

| TIME_OF_DAY | 0[0-5:59], 1[6:00-11:59], 2[12:00-17:59], 3[18:00-23:59] | integer | preferred | |

| SATIETY | 0: unknown, 1: post-prandial, 2: fasting | integer | preferred | |

| LMP | Number of days since start of last menstrual period (-1: male, 0: unknown) | integer | preferred | |

| retest 8 | RETEST DURATION | Time since baseline | real | core |

| RETEST_UNITS | m: min, d: days | string | core | |

| PRECEDING_CONDITION | 0: No active task, 1: active task, 2: music listening, 3: video watching, 4: unknown | integer | core | |

| TIME_OF_DAY | 0[0-5:59], 1[6:00-11:59], 2[12:00-17:59], 3[18:00-23:59] | integer | preferred | |

| SATIETY | 0: unknown, 1: post-prandial, 2: fasting | integer | preferred | |

| LMP | Number of days since start of last menstrual period (−1: male, 0: unknown) | integer | preferred | |

| retest 9 | RETEST DURATION | Time since baseline | real | core |

| RETEST_UNITS | m: min, d: days | string | core | |

| PRECEDING_CONDITION | 0: No active task, 1: active task, 2: music listening, 3: video watching, 4: unknown | integer | core | |

| TIME_OF_DAY | 0[0-5:59], 1[6:00-11:59], 2[12:00-17:59], 3[18:00-23:59] | integer | preferred | |

| SATIETY | 0: unknown, 1: post-prandial, 2: fasting | integer | preferred | |

| LMP | Number of days since start of last menstrual period (−1: male, 0: unknown) | integer | preferred |

Technical Validation

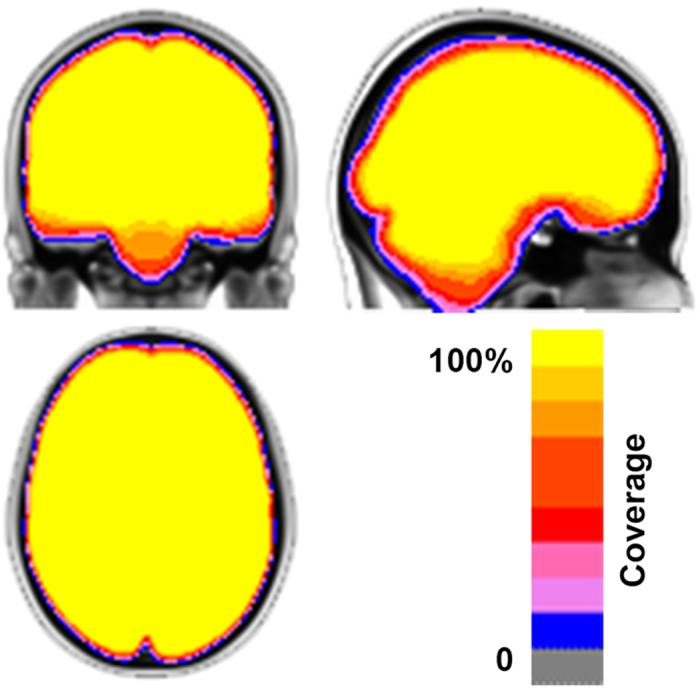

Consistent with the established FCP/INDI policy, all data contributed to CoRR was made available to users regardless of data quality. Justifications for this decision include the lack of consensus within the functional imaging community on criteria for quality assurance, and the utility of ‘lower quality’ datasets for facilitating the development of artifact correction techniques. For CoRR, the inclusion of datasets with significant artifacts related to factors such as motion are particularly valuable, as it enables the determination of the impact of such real-world confounds on reliability and reproducibility21,22. However, the absence of screening for data quality in the data release does not mean that the inclusion of poor quality datasets in imaging analyses is routine practice for the contributing sites. Figure 1 provides a summary map describing the anatomical coverage for rfMRI scans included in the CoRR dataset.

Figure 1. Summary map of brain coverage for rfMRI scans in CoRR (N=5,093).

The color indicates the coverage ratio of rfMRI scans.

To facilitate quality assessment of the contributed samples and selection of datasets for analyses by individual users23, we made use of the Preprocessed Connectome Project quality assurance protocol (http://preprocessed-connectomes-project.github.io), which includes a broad range of quantitative metrics commonly used in the imaging literature for assessing data quality, as follows. They are itemized below:

Spatial Metrics (sMRI, rfMRI)

o Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) 24. The mean within gray matter values divided by the standard deviation of the air values.

o Foreground to Background Energy Ratio (FBER)

o Entropy Focus Criteria (EFC) 25. Shannon’s entropy is used to summarize the principal directions distribution.

o Smoothness of Voxels 26. The full-width half maximum (FWHM) of the spatial distribution of image intensity values.

o Ghost to Signal Ratio (GSR) (only rfMRI) 27. A measure of the mean signal in the ‘ghost’ image (signal present outside the brain due to acquisition in the phase encoding direction) relative to mean signal within the brain.

o Artifact Detection (only sMRI) 28. The proportion of voxels with intensity corrupted by artifacts normalized by the number of voxels in the background.

o Contrast-to-Noise Ratio (CNR) (only sMRI) 24. Calculated as the mean of the gray matter values minus the mean of the white matter values, divided by the standard deviation of the air values.

Temporal Metrics (rfMRI)

o Head Motion

▪Mean framewise displacement (FD) 29. A measure of subject head motion, which compares the motion between the current and previous volumes. This is calculated by summing the absolute value of displacement changes in the x, y and z directions and rotational changes about those three axes. The rotational changes are given distance values based on the changes across the surface of a 50 mm radius sphere.

▪Percent of volumes with FD greater than 0.2 mm

▪Standardized DVARS. The spatial standard deviation of the temporal derivative of the data (D referring to temporal derivative of time series, VARS referring to root-mean-square variance over voxels)29, normalized by the temporal standard deviation and temporal autocorrelation (http://blogs.warwick.ac.uk/nichols/entry/standardizing_dvars).

o General

▪Outlier Detection. The mean fraction of outliers found in each volume using 3dTout command in the software package for Analysis of Functional NeuroImages (AFNI: http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/afni).

▪Median Distance Index. The mean distance (1-spearman’s rho) between each time-point’s volume and the median volume using AFNI’s 3dTqual command.

▪Global Correlation (GCOR) 30. The average of the entire brain correlation matrix, which is computed as the brain-wide average time series correlation over all possible combinations of voxels.

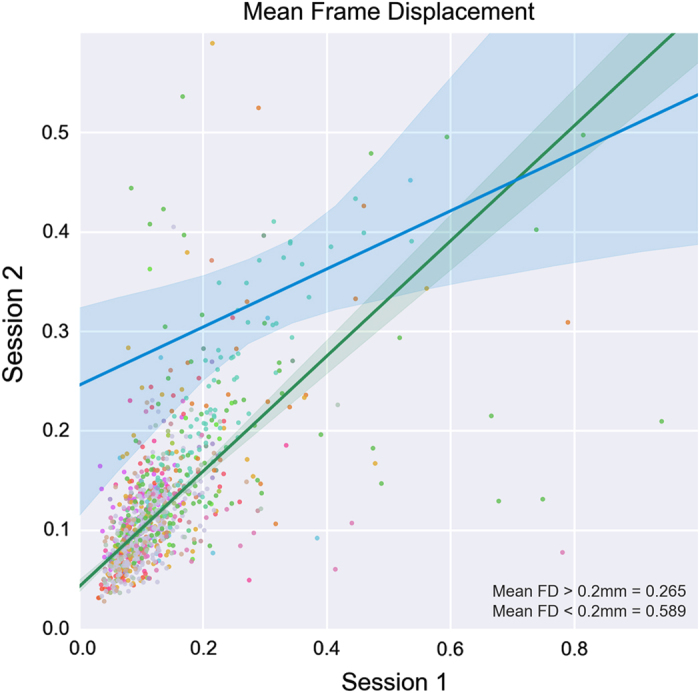

Imaging data preprocessing was carried out with the Configurable Pipeline for the Analysis of Connectomes (C-PAC: http://www.nitrc.org/projects/cpac). Results for the sMRI images (spatial metrics) are depicted in Supplementary Figure 1, for the rfMRI scans in Supplementary Figure 2 (general spatial and temporal metrics) and Supplementary Figure 3 (head motion). For both sMRI and rfMRI, the battery of quality metrics revealed notable variations in image properties across sites. It is our hope that users will explore the impact of such variations in quality on the reliability of data derivatives, as well as potential relationships with acquisition parameters. Recent work examining the impact of head motion on reliability suggests the merits of such lines of questioning. Specifically, Yan and colleagues found that motion itself has moderate test-retest reliability, and appears to contribute to reliability when low, though it compromises reliability when high31–33. Although a comprehensive examination of this issue is beyond the scope of the present work, we did verify that motion does have moderate test-retest reliability in the CoRR datasets (see Figure 2) as previously suggested. Interestingly, this relationship appeared to be driven by the lower motion datasets (mean FD<0.2mm). Future work will undoubtedly benefit from further exploration of this phenomena and its impact of findings.

Figure 2. Test-retest plots of in-scanner head motion during rfMRI.

Total 1019 subjects who have at least two rfMRI sessions are selected. The green line indicates the correlation between the two sessions within the lower motion datasets (mean FD<0.2 mm). The blue line indicates the correlation for the higher motion datasets (mean FD >0.2 mm).

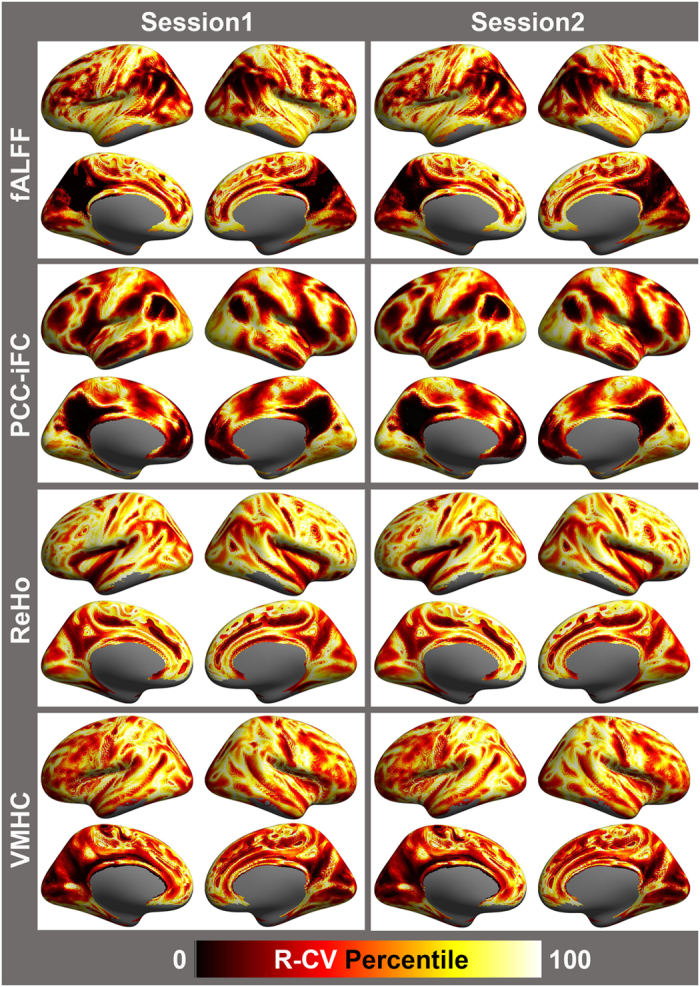

Beyond the above quality control metrics, a minimal set of rfMRI derivatives for the datasets were calculated for the datasets included in CoRR to further facilitate comparison of images across sites:

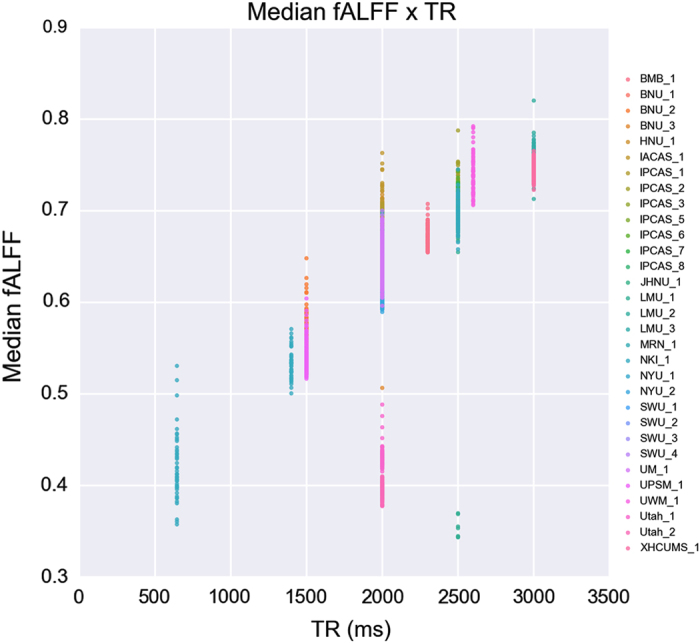

o Fractional Amplitude of Low Frequency Fluctuations (fALFF) 34,35. The total power in the low frequency range (0.01–0.1 Hz) of an fMRI image, normalized by the total power across all frequencies measured in that same image.

o Voxel-Mirrored Homotopic Connectivity (VMHC) 36,37. The functional connectivity between a pair of geometrically symmetric, inter-hemispheric voxels.

o Regional Homogeneity (ReHo) 38–40. The synchronicity of a voxel’s time series and that of its nearest neighbors based on Kendall’s coefficient of concordance to measure the local brain functional homogeneity.

o Intrinsic Functional Connectivity (iFC) of Posterior Cingulate Cortex (PCC) 41. Using the mean time series from a spherical region of interest (diameter=8 mm) centered in PCC (x=−8, y=−56, z=26)42, functional connectivity with PCC is calculated for each voxel in the brain using Pearson’s correlation (results are Fisher r-to-z transformed).

To enable rapid comparison of derivatives, we: (1) calculated the 50th, 75th, and 90th percentile scores for each participant, and then (2) calculated site means and standard deviations for each of these scores (see Table 6 (available online only)). We opted to not use increasingly popular standardization approaches (for example, mean-regression, mean centering +/− variance normalization) in the calculation of derivative values, as the test-retest framework provides users a unique opportunity to consider the reliability of site-related differences. As can be seen in Supplementary Figure 4, for all the derivatives, the mean value or coefficient of variation obtained for a site was highly reliable. In the case of fALFF, site-specific differences can be directly related to the temporal sampling rate (that is, TR; see Figure 3), as lower TR datasets include a broader range of frequencies in the denominator—thereby reducing the resulting fALFF scores (differences in aliasing are likely to be present as well). This note of caution about fALFF raises the general issue that rfMRI estimates can be highly sensitive to acquisition parameters7,13. Specific factors contributing to differences in the other derivatives are less obvious (it is important to note that the correlation-based derivatives have some degree of standardization inherent to them). Interestingly, the coefficient of variation across participants also proved to be highly reliable for the various derivatives; while this may point to site-related differences in the ability to detect differences across participants, it may also be some reflection of the specific populations obtained at a site (or the sample size). Overall, these site-related differences highlight the potential value of post-hoc statistical standardization approaches, which can be used to handle unaccounted for sources of variation within-site as well43.

Table 6. Descriptive statistics for common derivatives.

| site | falff_50_mean | falff_50_std | falff_75_mean | falff_75_std | falff_90_mean | falff_90_std | reho_50_mean | reho_50_std | reho_75_mean | reho_75_std | reho_90_mean | reho_90_std | vmhc_50_mean | vmhc_50_std | vmhc_75_mean | vmhc_75_std | vmhc_90_mean | vmhc_90_std |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMB_1 | 0.67187915 | 0.01095439 | 0.71275284 | 0.01375119 | 0.75674746 | 0.01764103 | 0.11483976 | 0.02234383 | 0.17367675 | 0.03054432 | 0.23555456 | 0.03477065 | 0.40005245 | 0.05349399 | 0.59060775 | 0.05345469 | 0.74120895 | 0.04415967 |

| UPSM_1 | 0.53848629 | 0.01365502 | 0.58279827 | 0.01723196 | 0.63421968 | 0.02156525 | 0.10928463 | 0.01861684 | 0.15879749 | 0.02548246 | 0.21595553 | 0.03151972 | 0.36652558 | 0.08059337 | 0.55897114 | 0.07633087 | 0.72308106 | 0.05822021 |

| LMU_1 | 0.68131285 | 0.07205763 | 0.71701862 | 0.07185605 | 0.75380735 | 0.07318461 | 0.19503535 | 0.01811093 | 0.26123735 | 0.02698287 | 0.34628153 | 0.0460762 | 0.36543758 | 0.08438397 | 0.57967558 | 0.10305263 | 0.75077383 | 0.07739737 |

| LMU_2 | 0.75128582 | 0.01154888 | 0.78492683 | 0.01157899 | 0.81470764 | 0.01302299 | 0.08188113 | 0.07398937 | 0.11549643 | 0.07391351 | 0.15802806 | 0.07467288 | 0.27874734 | 0.09491569 | 0.47506016 | 0.09555446 | 0.6654087 | 0.07868861 |

| LMU_3 | 0.75300309 | 0.01130565 | 0.78767158 | 0.01167477 | 0.81832079 | 0.0126824 | 0.08800187 | 0.01217619 | 0.12622061 | 0.020186 | 0.17269627 | 0.02807193 | 0.3391815 | 0.06357559 | 0.53838804 | 0.06600959 | 0.70707509 | 0.05175325 |

| HNU_1 | 0.65986927 | 0.02010203 | 0.72070762 | 0.02451698 | 0.77651227 | 0.02363225 | 0.2038152 | 0.03514323 | 0.29749165 | 0.04497476 | 0.38325751 | 0.05052365 | 0.4588192 | 0.05497453 | 0.63538063 | 0.04934746 | 0.77230292 | 0.03885562 |

| IPCAS_1 | 0.67044235 | 0.016092 | 0.73265578 | 0.02054316 | 0.78949274 | 0.02176515 | 0.16103934 | 0.01787039 | 0.23594238 | 0.02272643 | 0.30939742 | 0.0268952 | 0.46294367 | 0.04570625 | 0.64824828 | 0.03803198 | 0.7883282 | 0.0275335 |

| IPCAS_8 | 0.62967971 | 0.01925352 | 0.67052505 | 0.02387977 | 0.71691484 | 0.02876108 | 0.09530096 | 0.01353402 | 0.14184759 | 0.02166288 | 0.1948324 | 0.02725064 | 0.36661959 | 0.07089762 | 0.55197346 | 0.07581143 | 0.70837986 | 0.06042681 |

| IPCAS_3 | 0.63595724 | 0.01076589 | 0.68743886 | 0.01482221 | 0.74423368 | 0.01892027 | 0.11979874 | 0.01402373 | 0.18396178 | 0.01845976 | 0.24977681 | 0.02327644 | 0.40684854 | 0.06845373 | 0.60042805 | 0.06228979 | 0.75188672 | 0.04717628 |

| BNU_2 | 0.60229242 | 0.02920188 | 0.65412869 | 0.02554877 | 0.71380426 | 0.02530338 | 0.11757821 | 0.02282137 | 0.17708686 | 0.03426596 | 0.23930029 | 0.04184171 | 0.39161112 | 0.06085424 | 0.57577467 | 0.06092372 | 0.72323258 | 0.05214133 |

| Utah_2 | 0.39387042 | 0.00795506 | 0.43954022 | 0.01013165 | 0.48927946 | 0.01422875 | 0.09003811 | 0.0073556 | 0.13869799 | 0.01255276 | 0.199258 | 0.01605418 | 0.29095939 | 0.03879641 | 0.51411575 | 0.04272958 | 0.696097 | 0.03564367 |

| IPCAS_2 | 0.72243191 | 0.0181438 | 0.7615492 | 0.02058029 | 0.799527 | 0.02245114 | 0.11424405 | 0.01332137 | 0.17020604 | 0.01854308 | 0.22841676 | 0.02230091 | 0.38997572 | 0.0479311 | 0.57226243 | 0.04429783 | 0.72028097 | 0.03543431 |

| IPCAS_7 | 0.70453551 | 0.01044921 | 0.74220274 | 0.01239562 | 0.78069057 | 0.01499633 | 0.11302486 | 0.01391228 | 0.16486068 | 0.01887637 | 0.22047912 | 0.02306602 | 0.44019481 | 0.05222028 | 0.61713186 | 0.04193198 | 0.75632372 | 0.0310469 |

| IPCAS_4 | 0.61859584 | 0.00500133 | 0.67050929 | 0.00733894 | 0.73398443 | 0.00864194 | 0.15711392 | 0.01341702 | 0.24042446 | 0.01581406 | 0.32192849 | 0.01555375 | 0.33438623 | 0.04830237 | 0.53106513 | 0.03968627 | 0.70159497 | 0.02432706 |

| IBA_TRT | 0.61697087 | 0.01698959 | 0.67181163 | 0.02379427 | 0.73267667 | 0.02564145 | 0.15428888 | 0.01943454 | 0.22296525 | 0.02621619 | 0.28959599 | 0.03162183 | 0.49319222 | 0.06024092 | 0.66792044 | 0.05406984 | 0.79630123 | 0.04112627 |

| NYU_1 | 0.60403584 | 0.00560845 | 0.63578872 | 0.00704961 | 0.66602103 | 0.01062687 | 0.06655346 | 0.00876404 | 0.08898365 | 0.01330434 | 0.11775377 | 0.01752209 | 0.24062456 | 0.06428724 | 0.4098162 | 0.07451068 | 0.58509115 | 0.06925713 |

| SWU_3 | 0.64630782 | 0.01126605 | 0.69593592 | 0.0152442 | 0.75454278 | 0.01890379 | 0.124959 | 0.01111077 | 0.18522821 | 0.01390574 | 0.24769718 | 0.01560898 | 0.42335421 | 0.05311485 | 0.59702631 | 0.05107783 | 0.73650282 | 0.04191661 |

| JHNU_1 | 0.65301786 | 0.01257395 | 0.70823791 | 0.01853576 | 0.7656215 | 0.02257707 | 0.14548168 | 0.01738676 | 0.21816082 | 0.02548086 | 0.29086169 | 0.03104211 | 0.43962768 | 0.04908573 | 0.62718721 | 0.04797892 | 0.76920497 | 0.04042416 |

| IPCAS_6 | 0.70658553 | 0.0123221 | 0.74488307 | 0.01826713 | 0.78379522 | 0.02078967 | 0.10545752 | 0.01273462 | 0.15660753 | 0.02326668 | 0.21339069 | 0.03337394 | 0.34452537 | 0.04373743 | 0.53229765 | 0.04768446 | 0.69326661 | 0.04242879 |

| IPCAS_5 | 0.64256233 | 0.01487854 | 0.69059087 | 0.02347256 | 0.74449512 | 0.02796 | 0.11943758 | 0.0155287 | 0.17868678 | 0.02501478 | 0.23846551 | 0.03047227 | 0.4077564 | 0.05064864 | 0.59247696 | 0.05081532 | 0.73817232 | 0.04471268 |

| SWU_2 | 0.64974047 | 0.01289791 | 0.70310073 | 0.0188145 | 0.76135469 | 0.02277764 | 0.12797104 | 0.01927335 | 0.19042776 | 0.02500273 | 0.25444691 | 0.03008468 | 0.45193177 | 0.05525688 | 0.63140079 | 0.05077888 | 0.76819185 | 0.04285344 |

| BNU_1 | 0.63211946 | 0.00972767 | 0.67600309 | 0.01378115 | 0.72653647 | 0.01881311 | 0.10428446 | 0.01308989 | 0.15421598 | 0.01991249 | 0.21087879 | 0.02547435 | 0.35300216 | 0.05553608 | 0.53670762 | 0.05706393 | 0.69495155 | 0.04838126 |

| SWU_4 | 0.64154444 | 0.01429541 | 0.69082036 | 0.0203162 | 0.74711214 | 0.02426893 | 0.11653525 | 0.01383388 | 0.17615494 | 0.01984331 | 0.2391432 | 0.02410923 | 0.39455079 | 0.06615914 | 0.58018861 | 0.06404032 | 0.73106233 | 0.0485205 |

| XHCUMS_1 | 0.74545799 | 0.0078227 | 0.77938982 | 0.0088829 | 0.81059326 | 0.0107497 | 0.07256239 | 0.01079506 | 0.10624958 | 0.01963938 | 0.1511244 | 0.02958381 | 0.30188529 | 0.06824965 | 0.50331368 | 0.08017147 | 0.68419305 | 0.07082655 |

| IACAS_1 | 0.6895231 | 0.0300066 | 0.75245037 | 0.03322049 | 0.8018579 | 0.0332941 | 0.24198074 | 0.02482892 | 0.33039185 | 0.03241646 | 0.41397883 | 0.04006509 | 0.52029517 | 0.06943379 | 0.69257685 | 0.05949973 | 0.81463929 | 0.0401705 |

| UWM_1 | 0.73885091 | 0.02085548 | 0.78182404 | 0.0217158 | 0.82110711 | 0.02122855 | 0.18033792 | 0.02375627 | 0.26637009 | 0.03235537 | 0.34847208 | 0.03830241 | 0.43066953 | 0.06329518 | 0.62068197 | 0.05952193 | 0.76718269 | 0.04542059 |

| Utah_1 | 0.43180294 | 0.01134049 | 0.47441855 | 0.01467621 | 0.52603847 | 0.02023981 | 0.09954567 | 0.01276878 | 0.14814368 | 0.01833839 | 0.20506961 | 0.02249829 | 0.32673934 | 0.06492514 | 0.53635086 | 0.06411349 | 0.71313155 | 0.04848159 |

| MRN_1 | 0.65478119 | 0.01662275 | 0.7120571 | 0.02363398 | 0.76604944 | 0.02670331 | 0.15111643 | 0.02284248 | 0.2216864 | 0.02877418 | 0.29443578 | 0.03425655 | 0.48563286 | 0.06569892 | 0.67372623 | 0.0542015 | 0.80905918 | 0.0375586 |

| BNU_3 | 0.62995743 | 0.01655295 | 0.6739848 | 0.02082506 | 0.72541729 | 0.02575076 | 0.1084434 | 0.01530951 | 0.16294329 | 0.02273817 | 0.222565 | 0.02686687 | 0.36913241 | 0.0628315 | 0.5559278 | 0.06363683 | 0.71159108 | 0.05368372 |

| NYU_2 | 0.60924566 | 0.00834139 | 0.64618221 | 0.01101985 | 0.68359507 | 0.01529646 | 0.09548649 | 0.01852433 | 0.13417889 | 0.02440248 | 0.17756895 | 0.02930165 | 0.31585856 | 0.07920283 | 0.5005881 | 0.07993809 | 0.66899026 | 0.06534853 |

| UM_1 | 0.64465695 | 0.01904965 | 0.69641997 | 0.02274992 | 0.7489135 | 0.02579444 | 0.18495672 | 0.0263751 | 0.25570424 | 0.03319021 | 0.32440271 | 0.03714822 | 0.5210892 | 0.06289882 | 0.7000433 | 0.05041404 | 0.8275942 | 0.03329554 |

| SWU_1 | 0.63444905 | 0.01143149 | 0.6768667 | 0.01638089 | 0.72632754 | 0.02163575 | 0.12247162 | 0.01482465 | 0.17643713 | 0.02030604 | 0.23413699 | 0.02418896 | 0.38041606 | 0.05010822 | 0.55571521 | 0.0510355 | 0.70154697 | 0.04606569 |

| nki_rest_645 | 0.42075741 | 0.03601592 | 0.51325902 | 0.04760785 | 0.62189991 | 0.05329492 | 0.16792067 | 0.02582188 | 0.26346495 | 0.03860451 | 0.35137484 | 0.04565719 | 0.53317793 | 0.08586873 | 0.72076799 | 0.07001122 | 0.83808126 | 0.04968654 |

| nki_rest_1400 | 0.5329489 | 0.0157548 | 0.58441685 | 0.02376856 | 0.6584884 | 0.03356512 | 0.13901774 | 0.01651447 | 0.21431023 | 0.03082392 | 0.30258362 | 0.04254909 | 0.47995716 | 0.08000626 | 0.68036714 | 0.06892006 | 0.81266311 | 0.05198713 |

| nki_rest_2500 | 0.69885965 | 0.01782518 | 0.74602209 | 0.02094921 | 0.78988815 | 0.02365705 | 0.10835936 | 0.01536915 | 0.16690148 | 0.02466222 | 0.23075883 | 0.0325903 | 0.45334 | 0.06787562 | 0.65129144 | 0.05635185 | 0.79011133 | 0.03912288 |

Figure 3. Individual differences in fALFF and the temporal sampling rate (TR).

Median fALFF values across each individual whole brains are plotted against the corresponding TR for each site. Different colors indicate labels of different sites.

Finally, in Figure 4, we demonstrate the ability of the CoRR datasets to: (1) replicate prior work showing regional differences in inter-individual variation for the various derivatives that occur at ‘transition zones’ or boundaries between functional areas (even after mean-centering and variance normalization), and (2) show them to be highly reproducible across imaging sessions in the same sample. It is our hope that this demonstration will spark future work examining inter-individual variation in these boundaries and their functional relevance. These surface renderings and visualizations are carried out with the Connectome Computation System (CCS) documented at http://lfcd.psych.ac.cn/ccs.html and will be released to the public via github soon (https://github.com/zuoxinian/CCS).

Figure 4. Test-retest plots of individual variation-related functional boundaries.

Detection of functional boundaries was achieved via examination of voxel-wise coefficients of variation (CV) for fALFF, PCC, ReHo and VMHC maps. For the purpose of visualization, coefficients of variation were rank-ordered, whereby the relative degree of variation across participants at a given voxel, rather than the actual value, was plotted to better contrast brain regions. Ranking coefficients of variation (R-CV) efficiently identified regions of greatest inter-individual variability, thus delineating putative functional boundaries.

To facilitate replication of our work, for each of Figures 1, 2,3 and Supplementary Figures 1–4, we include a variable in the COINS phenotypic data that indicates whether or not each dataset was included in the analyses depicted. We also included this information in the phenotypic files on NITRC.

Usage Notes

While formal test-retest reliability or reproducibility analyses are beyond the scope of the present data description, we illustrate the broad range of potential questions that can be answered for rfMRI, dMRI and sMRI using the resource. These include the impact of:

Image quality13

Image processing decisions13,30,38,43,46–48 (for example, nuisance signal regression for rfMRI, spatial normalization algorithms, computational space)

Standardization approaches43

Age51–53

Of note, at present, the vast majority of studies do not collect physiological data, and this is reflected in the CoRR initiative. With that said, recent advances in model-free correction (for example, ICA-FIX54,55, CORSICA56, PESTICA57, PHYCAA58,59) can be of particular value in the absence of physiological data.

Additional questions may include:

How reliable are image quality metrics?

How does reliability and reproducibility impact prediction accuracy?

How do imaging modalities (for example, rfMRI, dMRI, sMRI) differ with respect to reproducibility and reliability? And within modality, are some derivatives more reliable than others?

Can reliability and reproducibility be used to optimize imaging analyses? How can such optimizations avoid being driven by artifacts such as motion?

How much information regarding inter-individual variation is shared and distinct among imaging metrics?

Which features best differentiate one individual from another?

One example analytic framework that can be used with the CoRR test-retest datasets is Non-Parametric Activation and Influence Reproducibility reSampling (NPAIRS60). By combining prediction accuracy and reproducibility, this computational framework can be used to assess the relative merits of differing image modalities, image metrics, or processing pipelines, as well as the impact of artifacts61–63.

Open access connectivity analysis packages that may be useful (list adapted from http://RFMRI.org):

Brain Connectivity Toolbox (BCT; MATLAB)64

BrainNet Viewer (BNV; MATLAB)65

Configurable Pipeline for the Analysis of Connectomes (C-PAC; PYTHON)66

CONN: functional connectivity toolbox (CONN; MATLAB)67

Dynamic Causal Model (DCM; MATLAB) as part of Statistical Parameter Mapping (SPM)68,69

Data Processing Assistant for Resting-State FMRI (DPARSF; MATLAB)70

Functional and Tractographic Connectivity Analysis Toolbox (FATCAT; C) as part of AFNI71,72

Seed-based Functional Connectivity (FSFC; SHELL) as part of FreeSurfer73

Graph Theory Toolkit for Network Analysis (GRETNA; MATLAB)74

Group ICA of FMRI Toolbox (GIFT; MATLAB)75

Multivariate Exploratory Linear Optimized Decomposition into Independent Components (MELODIC; C) as part of FMRIB Software Library (FSL)76,77

Neuroimaging Analysis Kit (NIAK: MATLAB/OCTAVE)78

Ranking and averaging independent component analysis by reproducibility (RAICAR; MATLAB)79,80

Resting-State fMRI Data Analysis Toolkit (REST; MATLAB)81

Additional information

Tables 2,3,4,5,6 are only available in the online version of this paper.

How to cite this article: Zuo, X.-N. et al. An open science resource for establishing reliability and reproducibility in functional connectomics. Sci. Data 1:140049 doi: 10.1038/sdata.2014.49 (2014).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is partially supported by the National Basic Research Program (973) of China (2015CB351702, 2011CB707800, 2011CB302201, 2010CB833903), the Major Joint Fund for International Cooperation and Exchange of the National Natural Science Foundation (81220108014, 81020108022) and others from Natural Science Foundation of China (11204369, 81270023, 81171409, 81271553, 81422022, 81271652, 91132301, 81030027, 81227002, 81220108013, 31070900, 81025013, 31070987, 31328013, 81030028, 81225012, 31100808, 30800295, 31230031, 91132703, 31221003, 30770594, 31070905, 31371134, 91132301, 61075042, 31200794, 91132728, 31271079, 31170980, 81271477, 31070900, 31170983, 31271087), the National Social Science Foundation of China (11AZD119), the National Key Technologies R&D Program of China (2012BAI36B01, 2012BAI01B03), the National High Technology Program (863) of China (2008AA02Z405, 2014BAI04B05), the Key Research Program (KSZD-EW-TZ-002) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the NIH grants (BRAINS R01MH094639, R01MH081218, R01MH083246, R21MH084126, R01MH081218, R01MH083246, R01MH080243, K08MH092697, R24-HD050836, R21-NS064464-01A1, 3R21NS064464-01S1), the Stavros Niarchos Foundation and the Phyllis Green Randolph Cowen Endowment. Dr Xi-Nian Zuo acknowledges the Hundred Talents Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Dr Michael P. Milham acknowledges partial support for FCP/INDI from an R01 supplement by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA; PAR-12-204), as well as gifts from Joseph P. Healey, Phyllis Green and Randolph Cowen to the Child Mind Institute. Dr Jiang Qiu acknowledges the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (2011) by the Ministry of Education. Dr Antao Chen acknowledges the support from the Foundation for the Author of National Excellent Doctoral Dissertation of PR China (201107) and the New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-11-0698). Dr Qiyong Gong would like to acknowledge the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University of China (IRT1272) and his Visiting Professorship appointment in the Department of Psychiatry at the School of Medicine, Yale University. The Department of Energy (DE-FG02-99ER62764) supported the Mind Research Network. Drs Xi-Nian Zuo and Michael P. Milham had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Data Citations

- Liu X., Nan W. Z., Wang K. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.ipcas4

- Zuo X. N. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.ipcas7

- Castellanos F. X., Di Martino A., Kelly C. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.nyu1

- Chen A. T., Lei X. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.swu3

- Chen A. T., Chen J. T. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.swu2

- Zang Y. F. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.bnu3

- Margulies D. S., Villringer A. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.bmb1

- Jiang T. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.iacas1

- Blautzik J., Meidl T. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.lmu3

- He Y., Lin Q. X., Gong G., Xia M. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.bnu1

- Liu J., Zhen Z. L. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.bnu2

- Wei G. X., Xu T., Luo J., Zuo X. N. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.ipcas8

- Lu G. M., Zhang Z. Q. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.jhnu1

- Qiu J., Wei D. T., Zhang Q. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.swu4

- Milham M. P., Colcombe S. J. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.nki1

- Li H. J., Hou X. H., Xu Y., Jiang Y., Zuo X. N. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.ipcas2

- Chen B., Ge Q., Zuo X. N., Weng X. C. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.hnu1

- Hallquist M., Paulsen D., Luna B. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.upsm1

- Blautzik J., Meindl T. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.lmu1

- Blautzik J., Meindl T. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.lmu2

- Yang Z. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.ipcas6

- LaConte S., Craddock C. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.ibatrt1

- Zhao K., Qu F., Chen Y., Fu X. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.ipcas1

- Liu X., Wang K. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.ipcas3

- Di Martino A., Castellanos F. X., Kelly C. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.nyu2

- Anderson J. S. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.utah1

- Chen A. T., Liu Y. J. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.swu1

- Bellec P. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.um1

- Anderson J. S., Nielsen J. A., Ferguson M. A. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.utah2

- Birn R. M., Prabhakaran V., Meyerand M. E. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.uwm1

- Mayer A. R., Calhoun V. D. 2014. Functional Connectomes Project International Neuroimaging Data-Sharing Initiative. http://dx.doi.org/10.15387/fcp_indi.corr.mrn1

References

- Alivisatos A. P. et al. The brain activity map project and the challenge of functional connectomics. Neuron 74, 970–974 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seung H. S. Neuroscience: Towards functional connectomics. Nature 471, 170–172 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. M. et al. Functional connectomics from resting-state fMRI. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17, 666–682 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner R. L., Krienen F. M. & Yeo B. T. Opportunities and limitations of intrinsic functional connectivity MRI. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 832–837 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporns O. Contributions and challenges for network models in cognitive neuroscience. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 652–660 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswal B. B. et al. Toward discovery science of human brain function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 4734–4739 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly C., Biswal B. B., Craddock R. C., Castellanos F. X. & Milham M. P. Characterizing variation in the functional connectome: promise and pitfalls. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16, 181–188 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk K. R. et al. Intrinsic functional connectivity as a tool for human connectomics: theory, properties, and optimization. J. Neurophysiol. 103, 297–321 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswal B., Yetkin F. Z., Haughton V. M. & Hyde J. S. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 34, 537–541 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo X. N. et al. Network centrality in the human functional connectome. Cereb. Cortex 22, 1862–1875 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. M. Correspondence of the brain’s functional architecture during activation and rest. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 13040–13045 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo B. T. et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 106, 1125–1165 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo X. N. & Xing X. X. Test-retest reliabilities of resting-state FMRI measurements in human brain functional connectomics: A systems neuroscience perspective. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 45, 100–118 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos F. X., Di Martino A., Craddock R. C., Mehta A. D. & Milham M. P. Clinical applications of the functional connectome. Neuroimage 80, 527–540 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S., Phillips A. G. & Insel T. R. Why has it taken so long for biological psychiatry to develop clinical tests and what to do about it? Mol. Psychiatry 17, 1174–1179 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh I. & Rose N. Biomarkers in psychiatry. Nature 460, 202–207 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennes M., Biswal B. B., Castellanos F. X. & Milham M. P. Making data sharing work: The FCP/INDI experience. Neuroimage 82, 683–691 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milham M. P. Open neuroscience solutions for the connectome-wide association era. Neuron 73, 214–218 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorgolewski J. K. et al. A high resolution 7-Tesla resting-state fMRI test-retest dataset with cognitive and physiological measures. Sci. Data 1, 140053 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott A. et al. COINS: An innovative informatics and neuroimaging tool suite built for large heterogeneous datasets. Front. Neuroinform 5, 33 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power J. D. et al. Methods to detect, characterize, and remove motion artifact in resting state fMRI. Neuroimage 84, 320–341 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo H. J. et al. Effective preprocessing procedures virtually eliminate distance-dependent motion artifacts in resting state FMRI. J. Appl. Math 13, 935154 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover G. H. et al. Function biomedical informatics research network recommendations for prospective multicenter functional MRI studies. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 36, 39–54 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnotta V. A. & Friedman L. Measurement of signal-to-noise and contrast-to-noise in the fBIRN multicenter imaging study. J. Digit. Imaging 19, 140–147 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzinfar M. et al. Entropy based DTI quality control via regional orientation distribution. Proc. IEEE Int. Symp. Biomed. Imaging 9, 22–26 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman L. et al. Test-retest and between-site reliability in a multicenter fMRI study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 29, 958–972 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davids M. et al. Fully-automated quality assurance in multi-center studies using MRI phantom measurements. Magn. Reson. Imaging 32, 771–780 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortamet B. et al. Automatic quality assessment in structural brain magnetic resonance imaging. Magn. Reson. Med 62, 365–372 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power J. D., Barnes K. A., Snyder A. Z., Schlaggar B. L. & Petersen S. E. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage 59, 2142–2154 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad Z. S. et al. Correcting brain-wide correlation differences in resting-state FMRI. Brain Connect 3, 339–352 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan C. G. et al. A comprehensive assessment of regional variation in the impact of head micromovements on functional connectomics. Neuroimage 76, 183–201 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk K. R., Sabuncu M. R. & Buckner R. L. The influence of head motion on intrinsic functional connectivity MRI. Neuroimage 59, 431–438 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L. L. et al. Neurobiological basis of head motion in brain imaging. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 6058–6062 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]