Abstract

Background and objectives

The primary goals were to re-examine whether sevelamer carbonate (SC) reduces advanced glycation end products (AGEs) (methylglyoxal and carboxymethyllysine [CML]), increases antioxidant defenses, reduces pro-oxidants, and improves hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and diabetic kidney disease (DKD). Secondary goals examined albuminuria, age, race, sex, and metformin prescription.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

This two-center, randomized, intention-to-treat, open-label study evaluated 117 patients with T2DM (HbA1c >6.5%) and stages 2–4 DKD (urinary albumin/creatinine ratio ≥200 mg/g) treated with SC (1600 mg) or calcium carbonate (1200 mg), three times a day, without changing medications or diet. Statistical analyses used linear mixed models adjusted for randomization levels. Preselected subgroup analyses of sex, race, age, and metformin were conducted.

Results

SC lowered serum methylglyoxal (95% confidence interval [CI], −0.72 to −0.29; P<0.001), serum CML (95% CI, −5.08 to −1.35; P≤0.001), and intracellular CML (95% CI, −1.63 to −0.28; P=0.01). SC increased anti-inflammatory defenses, including nuclear factor like-2 (95% CI, 0.58 to 1.29; P=0.001), AGE receptor 1 (95% CI, 0.23 to 0.96; P=0.001), NAD-dependent deacetylase sirtuin-1 (95% CI, 0.20 to 0.86; P=0.002), and estrogen receptor α (95% CI, 1.38 to 2.73; P ≤0.001). SC also decreased proinflammatory factors such as TNF receptor 1 (95% CI, −1.56 to −0.72; P≤0.001) and the receptor for AGEs (95% CI, −0.58 to 1.53; P≤0.001). There were no differences in HbA1c, GFR, or albuminuria in the overall group. Subanalyses showed that SC lowered HbA1c in women (95% CI, −1.71 to −0.27; P=0.01, interaction P=0.002), and reduced albuminuria in those aged <65 years (95% CI, −1.15 to −0.07; P=0.03, interaction P=0.02) and non-Caucasians (95% CI, −1.11 to −0.22; P=0.003, interaction P≤0.001), whereas albuminuria increased after SC and calcium carbonate in Caucasians.

Conclusions

SC reduced circulating and cellular AGEs, increased antioxidants, and decreased pro-oxidants, but did not change HbA1c or the albumin/creatinine ratio overall in patients with T2DM and DKD. Because subanalyses revealed that SC may reduce HbA1c and albuminuria in some patients with T2DM with DKD, further studies may be warranted.

Keywords: diabetic nephropathy, advanced glycation end product, albuminuria, ethnicity, oxidative stress

Introduction

Because CKD among patients with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is associated with increased mortality, early detection and management of diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is critical (1,2). The risk factors for the induction and progression of DKD are multifactorial and include hyperglycemia, inflammation, and oxidative stress (OS) (3,4). Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are important contributors to these risk factors because they induce both inflammation and OS (5). These changes significantly contribute to DKD and its complications in both humans and animal models (6–8). Although hyperglycemia promotes AGE formation, several clinical studies show that dietary AGEs are also significant contributors to AGEs in patients with diabetes (9,10). These data suggest that reducing the amount of AGEs in the diet could be a useful strategy for improving the management of diabetic complications. This concept was confirmed in studies showing that ingestion of foods with high AGE levels was a significant determinant of insulin resistance, increased inflammation, and reduced key antioxidant defenses, including NAD-dependent protein deacetylase surtuin-1 (SIRT1), advanced glycation end product receptor 1 (AGER1), and adiponectin in T2DM (11–13).

Because dietary modifications have often proven difficult to implement, we previously sought a drug that might prevent the uptake of AGEs from the diet (14). We found that sevelamer carbonate (SC) bound AGEs and reduced hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), serum and cellular AGE levels, and markers of inflammation in an 8-week crossover intention-to-treat trial of T2DM patients with DKD (14). On the basis of these data and studies showing that close control of glycemia reduces the risk of DKD progression (15) and that inflammation correlates with DKD (4), we hypothesized that a longer and larger trial might show that SC could also reduce albuminuria. Finally, because age (2), sex (16), and race (17) have been shown to affect DKD, these factors were chosen for secondary analysis.

Therefore, this study had the primary goals of re-examining whether the addition of SC to existing diabetes management reduces AGEs, increases antioxidant defenses, reduces pro-oxidants, and improves HbA1c. Secondary goals included determination of whether SC would improve albuminuria and if age, race, sex, and metformin prescription affect these responses.

Materials and Methods

Patients with T2DM treated with one or more diabetes medications, HbA1c>6.5%, with albuminuria (>200 mg urinary albumin/g creatinine; albumin/creatinine ratio [ACR]), and stages 2–4 DKD were recruited from the Mount Sinai Health System clinics and one private practice site. Exclusion criteria included hypophosphatemia (<2.4 mg/dl), hyperphosphatemia (>4.5 mg/dl), hypercalcemia (>10.5 mg/dl), biopsy-proven renal disease other than DKD, symptomatic gastrointestinal disorders, significant gastrointestinal surgery, and concomitant inflammatory diseases. Fasting blood, anthropometric parameters, 3-day food records, and a first morning urine sample were obtained at randomization and at 3 and 6 months. As a safety measure, blood samples were obtained at 1 and 2 weeks to assess serum calcium and phosphate. The study (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01493050) was approved by the Mount Sinai and Beth Israel Medical Center Institutional Review Boards and all patients signed informed consent forms, consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study Design

This two-center, randomized, single-blinded (patients and laboratory personnel were blinded) intention-to-treat study did not alter diet or medical care. Most patients received insulin, metformin (48%), other oral antidiabetic drugs, statins, aspirin, and one or more antihypertensive drugs. Daily multivitamin supplements, containing 400 IU cholecalciferol (Nature’s Bounty Inc, Bohemia, NY), were provided.

Patients were randomized to receive either SC (1600 mg three times daily with meals) or calcium carbonate (CC) (1200 mg three times daily with meals) based on the study design of the previous crossover trial (14).

On the basis of previous studies of patients with T2DM in whom the effects of lowering AGEs in the diet were evaluated (11), several markers were assessed at 3 and 6 months. These included ACR, GFR, plasma HbA1c and fibroblast growth factor 23, serum AGEs and AGEs in PBMCs (intracellular AGEs), mRNA levels of cellular antioxidants (SIRT1, AGER1, estrogen receptor α [ERα], and nuclear factor like-2 [Nrf2]) and inflammation (TNF receptor 1 [TNFR1] and receptor for advanced glycation endproducts [RAGE]), and serum antioxidants (adiponectin) and oxidants (plasma 8-isoprostanes, vascular adhesion molecule 1, and serum leptin).

Compliance was checked by pill count on a weekly basis. A research coordinator contacted patients at least weekly.

Dietary Intake

Detailed dietary assessments were obtained at randomization and at 3 and 6 months. Study patients were encouraged to maintain their usual diet. Nutrient, mineral, and AGE intake was estimated from food records using a nutrient software program (Food Processor version 10.1; Esha Research, Salem, OR) and a food-AGE database (18,19). AGE intake was expressed as equivalents (1 equivalent=1×106 units).

Blood and Urine Tests

The Mount Sinai Medical Center laboratory performed clinical measurements as well as plasma HbA1c and fibroblast growth factor 23 and serum cystatin C measurements. Leptin, adiponectin, 8-isoprostanes, and vascular adhesion molecule 1 were tested in duplicate by commercial ELISA kits in the laboratory of H.V. (14). All analyses were performed on blinded samples. The ACR was calculated from values measured by the Mount Sinai Medical Center laboratory. eGFR was determined using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration cystatin C-creatinine equation (20–22).

Measurement of AGEs

Serum, urine, and intracellular carboxymethyllysine (CML) and methylglyoxal (MG) were quantified by ELISA using two non–cross-reactive mAbs that recognize lipid and protein AGEs (interassay coefficients of variation, 2.8% and 5.2% for CML and MG, respectively; intra-assay coefficients of variation, 2.6% and 4.1% for CML and MG, respectively) (23).

Quantitative RT-PCR Assay

PBMCs were separated by Ficoll-Hypaque Plus gradient (American Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden) and lysed, and proteins were extracted (14). Total RNA was extracted using Trizol (Molecular Probes Inc) (RNA OD280/260 ratio, 1.8–2.0). RNA was reverse transcribed using Superscript III RT (Invitrogen). Nrf2, AGER1, SIRT1, TNFR1, and RAGE mRNA expression was analyzed by quantitative SYBR Green RT-PCR, as described (14). The transcript copy number of target genes was determined based on cycle threshold (Ct) values.

Western Blot Analyses

PBMC lysates were sonicated in 500 μl lysis buffer (New England Biolabs) and proteins were separated on 8% SDS-PAGE gels, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and visualized by chemiluminescence (Roche) (14). Bound immune complexes in radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer were used for immunoblotting after SDS-PAGE and transfer to nitrocellulose membranes.

Statistical Analyses

Data were initially cleaned to identify and remove extreme outliers (two values [one for SIRT1, and one for ACR], which exceeded more than four times the next largest value were deleted). Variables that were approximately symmetric in distribution were summarized using their mean and SD. Highly skewed variables were summarized using their three quartiles. Binary variables were summarized by percentages. Linear mixed models were used to estimate and test the difference between treatments in results averaging over the 3- and 6-month visits, adjusting for initial levels at baseline. Prespecified secondary analyses were subgroup analyses by age (split at the median, 65 years), sex, race (Caucasian versus non-Caucasian), and use of metformin at randomization. Subgroup by treatment interactions were tested by adding interaction terms to the linear mixed models. Only variables for which there was evidence of an interaction between subgroup and treatment are reported. Analysis was by intention to treat. A priori, it was decided that no correction should be made for multiple significance testing, nor adjustment made for confounders; significance was to be reported when the P value was ≤0.05 in all cases. Because adjustment for multiple testing is controversial, we made an a priori decision that it not be included in our statistical analysis plan. However, because some may be interested in this, we did perform standard Bonferroni adjustments for multiple significance testing. There were 20 tests done in the primary analysis and 80 tests of interactions. Therefore, one should expect at least one result to be significant, even if the null hypothesis were true. Analyses were performed with SAS (version 9.3) and Stata (version 12) software.

Results

Study Population

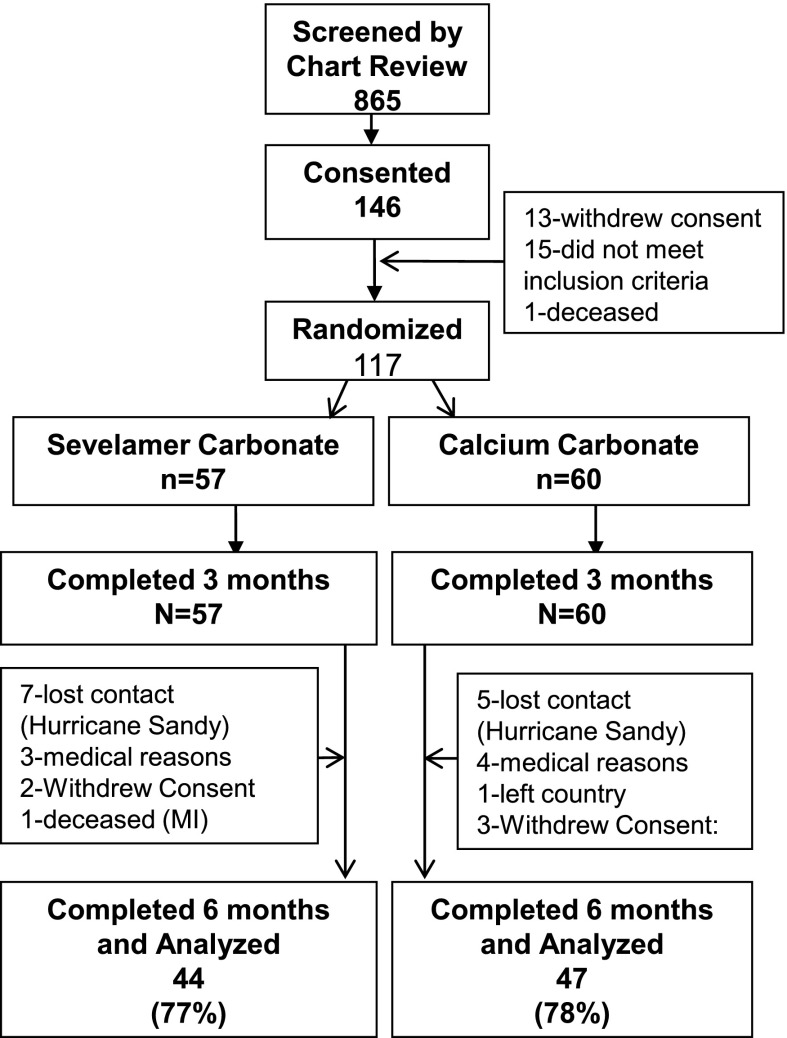

Of 865 clinic records screened, 146 patients met the inclusion criteria, 120 were invited to participate, and 117 agreed and were randomized (Figure 1). This number was calculated to give an 85% chance of finding a 20% change in AGEs with 5% type I error based on the crossover study. There were 117 patients who completed the 3-month follow-up, but Hurricane Sandy contributed to a reduced number and 91 patients completed the 6-month follow-up. At randomization, 56% of patients were men, 45% were Caucasian (24), and the mean age was 63.4 years (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study design. MI, myocardial infraction.

Table 1.

Baseline summary statistics

| Variable | All Study Patients (N=117) | Sevelamer Carbonate Arm (n=57) | Calcium Carbonate Arm (n=60) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 56 | 51 | 62 |

| Caucasian race | 45 | 49 | 38 |

| Metformin use (yes) | 48 | 50 | 48 |

| Age (yr) | 63.4 (9.8) | 63.5 (10.2) | 63.2 (9.6) |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 137 (18) | 137 (18) | 138 (18) |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 75.9 (10.8) | 73.5 (9.9) | 78.3 (11.1) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 171 (50) | 175 (49) | 166 (51) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 155 (94, 181) | 172 (94, 208) | 140 (90, 179) |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 51.6 (17.0) | 54.0 (17.4) | 49.4 (16.5) |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 89.5 (42.6) | 90.1 (38.6) | 88.9 (46.4) |

| Waist/hip circumference | 0.977 (0.069) | 0.976 (0.070) | 0.978 (0.069) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 33.2 (7.4) | 34.0 (7.2) | 32.5 (7.2) |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.68 (1.92) | 8.87 (1.65) | 8.50 (2.08) |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 153 (71) | 161 (76) | 145 (66) |

| Cystatin C (mg/dl) | 1.63 (0.64) | 1.61 (0.66) | 1.64 (0.63) |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 48.6 (21.5) | 50.1 (22.3) | 47.2 (20.9) |

| ACR (µg/mg) | 615 (48, 1003) | 683 (66, 1222) | 550 (45, 799) |

| FGF-23 (µg/dl) | 23.4 (8.2, 22.5) | 27.6 (7.9, 21.0) | 19.2 (8.9, 23.0) |

| Adiponectin (µg/ml) | 9.82 (7.94) | 10.03 (7.38) | 9.63 (7.16) |

| Leptin (ng/ml) | 15.0 (3.7, 17.6) | 13.9 (3.7, 16.8) | 10.1 (3.7, 20.9) |

| Nrf2 (mRNA) | 0.36 (0.06, 0.34) | 0.30 (0.04, 0.33) | 0.42 (0.08, 0.36) |

| SIRT1 (mRNA) | 0.20 (0.03, 0.14) | 0.13 (0.02, 0.12) | 0.27 (0.04, 0.16) |

| AGER1 (mRNA) | 0.20 (0.04, 0.16) | 0.12 (0.03, 0.14) | 0.28 (0.05, 0.19) |

| ERα (mRNA) | 0.30 (0.005, 0.193) | 0.25 (0.003, 0.209) | 0.34 (0.005, 0.143) |

| Serum CML (U/ml) | 36.2 (8.4) | 36.1 (5.9) | 36.3 (10.3) |

| Serum MG (nmol/ml) | 3.58 (0.72) | 3.60 (0.61) | 3.58 (0.81) |

| Intracellular CML (U/mg protein) | 6.89 (2.35) | 6.96 (2.37) | 6.82 (2.35) |

| Intracellular MG (nmol/mg protein) | 0.516 (0.233) | 0.519 (0.212) | 0.514 (0.255) |

| RAGE (mRNA) | 0.20 (0.05, 0.20) | 0.28 (0.06, 0.42) | 0.13 (0.05, 0.15) |

| TNFR1 (mRNA) | 0.20 (0.02, 0.11) | 0.31 (0.03, 0.13) | 0.09 (0.01, 0.07) |

| 8-isoprostanes (pg/ml) | 74.3 (64.6) | 89.3 (67.8) | 60.2 (538.5) |

| VCAM-1 (ng/ml) | 986 (702, 1291) | 1022 (774, 1304) | 952 (672, 1186) |

Data are given as the percentage, mean (SD), or median (first quartile, third quartile) unless otherwise indicated. Transcript copy numbers were counted for mRNA. BMI, body mass index; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; ACR, albumin/creatinine ratio; FGF-23, fibroblast growth factor 23; Nrf2, nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2; SIRT1, NAD-dependent deacetylase sirtuin-1; AGER1, advanced glycation end product receptor 1; ERα, estrogen receptor α; CML, carboxymethyllysine; MG, methylglyoxal; RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation endproducts; TNFR1, TNF receptor 1; VCAM-1, vascular adhesion molecule 1.

Effect of SC on AGEs and Inflammation

Pro-oxidants.

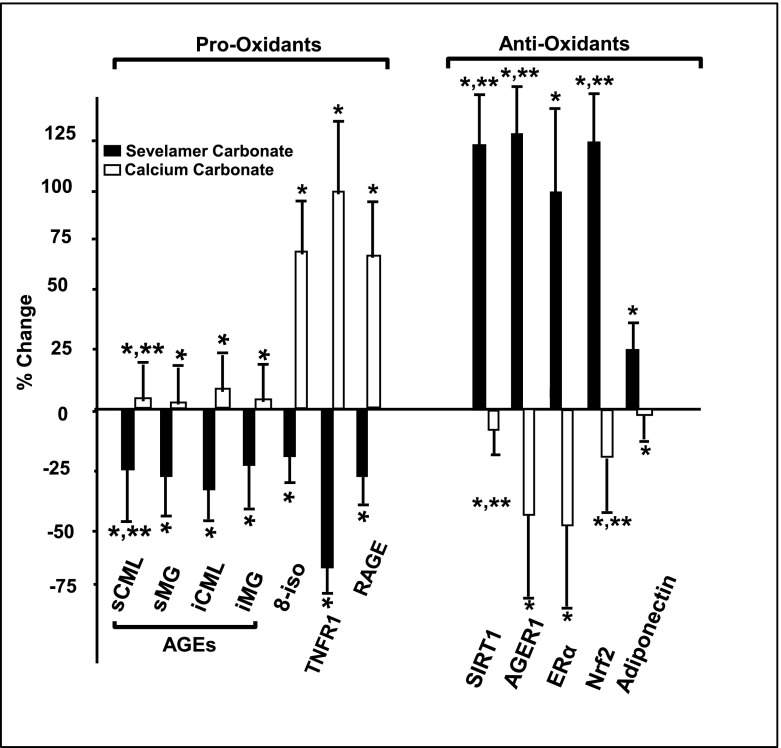

Most pro-oxidant factors, including serum CML (U/ml) (mean difference [MD] −3.21; 95% confidence interval [CI], −5.08 to −1.35; P<0.001), MG (nmol/ml) (MD −0.51; 95% CI, −0.72 to −0.29; P<0.001), intracellular CML (MD −0.95; 95% CI, −1.63 to −0.28; P=0.01), and mRNAs including full-length RAGE and TNFR1 were lower in the SC cohort, but they either remained stable or were higher in the CC cohort (transcript copy number of target genes was determined based on Ct values) (Figure 2, Table 2, Supplemental Table 1). Although intracellular MG and 8-isoprostanes were not changed in the overall SC cohort, both were lower in the patients aged <65 years (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Effect of sevelamer carbonate and calcium carbonate on circulating and intracellular AGEs and pro-oxidant and inflammatory factors and antioxidant/anti-inflammatory factors in type 2 diabetes mellitus with diabetic kidney disease. After 6 months on sevelamer carbonate (closed bars) or calcium carbonate (open bars), changes are shown as the percentage from randomization levels (mean±SD). *P≤0.05, statistical significance in percent changes between sevelamer carbonate (SC) and calcium carbonate (CC) groups; **P≤0.05, significance between randomization and mean of the 3- and 6-month values within each group. s, serum; CML, carboxymethyllysine; MG, methylglyoxal; i, intracellular; 8-iso, 8-isoprostane; TNFR1, TNF receptor 1; RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation end products; AGE, advanced glycation end product; SIRT1, NAD-dependent deacetylase sirtuin-1; AGER1, advanced glycation end product receptor 1; ERα, estrogen receptor α; Nrf2, nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2.

Table 2.

Mean differences after treatment: Sevelamer carbonate minus calcium carbonate, averaged over visits 3 and 6 and adjusted for baseline values

| Variable | Mean (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic factor | ||

| HbA1c (%) | −0.22 (−0.64 to 0.21) | 0.32 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | −0.004 (−0.14 to 0.13) | 0.95a |

| Renal function related | ||

| Cystatin C (mg/L) | 0.090 (−0.19 to 0.28) | 0.35 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | −0.048 (−0.16 to 0.07) | 0.40a |

| ACR (μg/mg) | −0.11 (−0.49 to 0.27) | 0.58a |

| FGF-23 (mg/ml) | −0.14 (−0.37 to 0.10) | 0.26a |

| Advanced glycation end product | ||

| Serum CML (U/ml) | −3.21 (−5.08 to −1.35) | <0.001 |

| Serum MG (nmol/ml) | −0.51 (−0.72 to −0.29) | <0.001 |

| Intracellular CML (U/mg protein) | −0.95 (−1.63 to −0.28) | 0.01 |

| Intracellular MG (nmol/mg protein) | −0.065 (−0.14 to 0.01) | 0.08 |

| Antioxidant | ||

| AGER1 (mRNA) | 0.60 (0.23 to 0.96) | 0.001a |

| ERα (mRNA) | 2.05 (1.38 to 2.73) | <0.001a |

| Nrf2 (mRNA) | 0.93 (0.58 to 1.29) | <0.001a |

| SIRT1 (mRNA) | 0.53 (0.20 to 0.86) | 0.002a |

| Leptin (ng/dl) | −0.008 (−0.26 to 0.24) | 0.95a |

| Pro-Oxidant | ||

| RAGE (mRNA) | −1.00 (−1.43 to −0.58) | <0.001a |

| TNFR1 (mRNA) | −1.14 (−1.56 to −0.72) | <0.001a |

| Adiponectin (mg/ml) | 1.35 (0.25 to 2.46) | 0.02 |

| 8-isoprostanes (pg/ml) | −0.10 (−0.41 to 0.20) | 0.50a |

| VCAM-1 (ng/ml) | −0.061 (−0.18 to 0.05) | 0.30a |

Results are shown as the mean of the values at 3 and 6 months in the sevelamer carbonate group minus the mean of the values of calcium carbonate adjusted for the baseline values of the index. Transcript copy numbers were counted for mRNA.

Difference and associated P value after a logarithmic transformation.

Table 3.

Significant subgroups (age, sex, race, and metformin use at baseline) by biomarker interactions

| Variable and Subgroup | Mean (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value for Interactiona |

|---|---|---|

| HbA1c (%) | ||

| Men | 0.36 (−0.11 to 0.84) | 0.002 |

| Women | −0.99 (−1.71 to −0.27) | |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | ||

| Men | 0.12 (−0.06 to 0.30) | 0.05 |

| Women | −0.15 (−0.35 to 0.05) | |

| ACR (μg/mg) | ||

| Age <65 y | −0.61 (−1.15 to −0.07) | 0.01 |

| Age ≥65 y | 0.37 (−0.21 to 0.94) | |

| Not Caucasian | −0.67 (−1.11 to −0.22) | 0.004 |

| Caucasian | 0.65 (0.02 to 1.28) | |

| ERα (mRNA) | ||

| No metformin | 1.47 (0.66 to 2.29) | 0.05 |

| Metformin | 2.96 (1.79 to 4.13) | |

| Intracellular MG (nmol/mg protein) | ||

| Age <65 y | −0.15 (−0.24 to −0.05) | 0.02 |

| Age ≥65 y | 0.02 (−0.08 to 0.12) | |

| 8-isoprostanes (pg/ml) | ||

| Not Caucasian | 0.14 (−0.17 to 0.46) | 0.01 |

| Caucasian | −0.53 (−1.00 to −0.07) |

Antioxidants.

Of the antioxidants tested, adiponectin (mg/ml) (MD 1.35; 95% CI, 0.25 to 2.46; P=0.02) and PBMC mRNAs including Nrf2 (MD 0.93; 95% CI, 0.58 to 1.29; P<0.001), AGER1 (MD 0.61; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.96; P<0.001), and ERα (MD 2.05; 95% CI, 1.38 to 2.73; P<0.001) were higher in the SC cohort (transcript copy number of target genes was determined based on Ct values) (Figure 2, Table 2, Supplemental Table 1). These factors were not changed in patients by CC. Interestingly, ERα mRNA levels were higher in the SC group in both sexes compared with randomization levels.

Substudy Analyses of Outcomes Showing Significant Interactions: HbA1c, ACR, and 8-Isoprostanes.

There were no differences in the overall population with respect to HbA1c, ACR, or 8-isoprostanes after SC or CC treatment. There were three differences detected based on sex, age, and race. First, HbA1c (%) was lower in women in the SC treatment arm compared with CC (mean −0.99; CI, −1.71 to −0.27), but not in men (interaction P=0.002) (Table 3, Supplemental Table 1). Second, ACR (μg/mg) levels were lower in patients aged <65 years (mean −0.61; CI, −1.15 to −0.61) than in patients aged >65 years (interaction P=0.01) and were lower in non-Caucasians (mean −0.67; CI, −1.11 to 0.22) than in Caucasians (interaction P=0.004) in the SC arm, whereas ACR increased in Caucasians (Tables 2 and 3). Finally, 8-isoprostanes (pg/ml) were lower in Caucasians compared with non-Caucasians (mean 0.53; CI, −1.00 to −0.07; interaction P=0.01) (Supplemental Table 1).

Sensitivity Analyses.

If the standard Bonferroni adjustments for multiple significance testing are followed, Nrf2, SIRT1, AGER1, ERα, serum CML, serum MG, RAGE, and TNFR1 show significant differences between treatments.

Dietary Intake.

There were no differences in the amount or type of nutrients or levels of AGEs in the patients’ diets from randomization to study end, within or between cohorts.

Compliance.

Pill count did not differ by drug assignment, and compliance was 55% in the SC arm and 60% in the CC arm at study end, a finding similar to other studies of these interventions (25,26).

Drug-Related Complications and Study Participant Removal/Loss.

Mild constipation and occasional cramping were present in approximately 10% of patients and did not differ between the SC and CC arms, consistent with previous clinical trials (26,27). There were no serious adverse events in either the SC or CC treatment arm. Of 117 randomized patients, all finished 3 months and 91 patients finished 6 months. Among those lost to follow-up, 12 were dislocated by Hurricane Sandy. The number lost to follow-up did not differ by drug assignment or randomization characteristics.

Discussion

Reducing AGEs in food lowers circulating AGEs and inflammation, restores key antioxidant host defenses, and improves glucose/insulin metabolism in humans and animals (11,28). This study confirmed that adding a nonabsorbed oral drug that binds AGEs (SC) to the management of fully treated patients with T2DM with DKD can reduce the levels of systemic and cellular AGEs, restore levels of several innate defenses, improve inflammation, and reduce chronic OS compared with CC treatment (14). Because dietary AGE consumption did not vary during the trial, the effect of SC appeared to result from reducing intestinal absorption of AGEs.

HbA1c was not reduced by SC in the overall population, but was reduced in women with T2DM and DKD. This suggests that adding SC to current treatment regimens may improve glucose metabolism in women. Although the mechanism is unclear, previous studies suggest that reduction of AGEs is associated with decreased insulin resistance that could result in better glucose homeostasis in T2DM (11).

Albuminuria is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and an all-cause mortality risk factor in progressive DKD, and directly correlates with albuminuria and inversely with eGFR in T2DM (29,30). Thus, although a reduction of ACR was not found in the overall study, the reduction of albuminuria found herein in patients aged <65 years and in non-Caucasians is of interest and should be examined in a larger study.

We previously found that AGEs and OS increase and innate antioxidant defenses decrease with age (23). Because the mean age of the cohort was 65 years, we compared the responses to SC and CC in patients aged <65 years with those aged >65 years. SC improved antioxidant defenses (AGER1, Nrf2, ERα, and SIRT1) and decreased inflammation (RAGE and TNFR1) in both age groups compared with CC. The relevance of these data to patients with T2DM and CKD is that increased inflammation, in particular TNFR1, is directly correlated with the progressive decline of renal function in T2DM with CKD (3,4,31).

Reducing AGEs by dietary AGE restriction protects against the loss of host defenses such as SIRT1 and AGER1 in T2DM (32). The effects of SC on AGEs in this study, compared with CC, confirms previously demonstrated relationships between AGEs and host defenses among older patients with T2DM and DKD (33). SC was also associated with a modest increase in the levels of ERα, a component of the anti-OS system (16)—a change that was greater in women than men, regardless of age. The reasons underlying sex-related differences in SC responses are unknown but lend support to evidence suggesting that elevated AGEs contribute to the loss of ERα function (34).

The incidence of diabetes and its complications, including DKD, differs among races (35,36). Although AGE levels were lower after SC treatment compared with CC treatment, the ACR was not reduced in the whole population in the overall study but was lower in non-Caucasians. The mechanism for this difference in response is unclear, but the incidence and rate of progression of DKD are higher in non-Caucasians with T2DM (17,36). Thus, changes in factors favoring DKD progression, such as AGE-induced chronic inflammation, might be more easily detectable in non-Caucasians.

Among the limitations of this study is the loss of patients, in part due to displacement after Hurricane Sandy. Other limitations include the short duration of intervention, the development of medical conditions requiring withdrawal such as ESRD, and the fact that subgroup analyses are likely to find false positives due to the high number of comparisons performed. Thus, statistical values need to be interpreted with caution and considered only when the biologic effects are consistent across different mechanisms. Finally, this study underlines the need to consider age, race, and sex in the design, conduct, and analysis of studies of patients with T2DM and DKD.

In summary, the addition of SC, a drug with a favorable benefit/risk profile, to the treatment plan of patients with T2DM and DKD results in decreased AGE levels and an improvement in innate defense homeostasis compared with adding CC to their treatment. SC had no effect on ACR or HbA1c in the overall group, but subgroup analyses did reveal significant changes. Thus, reducing the amount of AGEs delivered to the gut, by SC, may be an effective additive to current strategies for reducing AGEs and inflammation in patients with T2DM. These results must be validated in a larger and longer trial.

Disclosures

This independent investigator-initiated trial was funded by a contract (to provide drugs, laboratory tests, and support for study staff) between G.E.S. and H.V. and Genzyme Corporation, a Sanofi Company. Ronal Tamler and G.E.S. consult for Sanofi, Jaime Uribarri consults for Salix Pharmaceuticals, and M.W. is a consultant for Novartis and Amgen. All financial interests were reported to and approved by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the faculty of several departments and divisions as well as many residents, fellows, staff, and faculty within the Mount Sinai Health System who assisted in the conduct of this study. We also acknowledge the invaluable assistance of the Clinical Research Unit and the members of the Data Monitoring Committee.

The Writing Committee (E.M.Y.S., M.W., L.P., H.V., and G.E.S.) accepts full responsibility for the content of this report and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

The following investigators comprise the AGE-less Study Group: Elena M. Yubero-Serrano, Mark Woodward, Leonid Poretsky, Helen Vlassara, Gary E. Striker, Agustin Busta, Nikolas B. Harbord, Kobena Dadzie, Julie Islam, Usman Ali, Ronald Tamler, Grishma Parikh, Eliot Rayfield, Luba Rakhlin, Jaime Uribarri, Rebecca Kent, Kamala Mantha-Thaler, Lynn Polmanteer, Megan Fendt, Anita Kalaj, Elizabeth McKee, Elizabeth Tripp, Renata A. Pyzik, Lauren Tirri, Johanna F. Kruckelmann, Shobha M. Swamy, Xue Chen, Weijing Cai, and Sharon J. Elliot.

Footnotes

Present address: Dr. Elena M. Yubero-Serrano, Lipid and Atherosclerosis Research Unit, Maimonides Institute of Biomedical Research of Cordoba, Reina Sofia University Hospital, University of Cordoba, Cordoba, Spain.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.07750814/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Afkarian M, Sachs MC, Kestenbaum B, Hirsch IB, Tuttle KR, Himmelfarb J, de Boer IH: Kidney disease and increased mortality risk in type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 302–308, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hallan SI, Matsushita K, Sang Y, Mahmoodi BK, Black C, Ishani A, Kleefstra N, Naimark D, Roderick P, Tonelli M, Wetzels JF, Astor BC, Gansevoort RT, Levin A, Wen CP, Coresh J, Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium : Age and association of kidney measures with mortality and end-stage renal disease. JAMA 308: 2349–2360, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gohda T, Niewczas MA, Ficociello LH, Walker WH, Skupien J, Rosetti F, Cullere X, Johnson AC, Crabtree G, Smiles AM, Mayadas TN, Warram JH, Krolewski AS: Circulating TNF receptors 1 and 2 predict stage 3 CKD in type 1 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 516–524, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skupien J, Warram JH, Niewczas MA, Gohda T, Malecki M, Mychaleckyj JC, Galecki AT, Krolewski AS: Synergism between circulating tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 and HbA(1c) in determining renal decline during 5-18 years of follow-up in patients with type 1 diabetes and proteinuria. Diabetes Care 37: 2601–2608, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai W, Ramdas M, Zhu L, Chen X, Striker GE, Vlassara H: Oral advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) promote insulin resistance and diabetes by depleting the antioxidant defenses AGE receptor-1 and sirtuin 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: 15888–15893, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bucala R, Makita Z, Vega G, Grundy S, Koschinsky T, Cerami A, Vlassara H: Modification of low density lipoprotein by advanced glycation end products contributes to the dyslipidemia of diabetes and renal insufficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91: 9441–9445, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makita Z, Radoff S, Rayfield EJ, Yang Z, Skolnik E, Delaney V, Friedman EA, Cerami A, Vlassara H: Advanced glycosylation end products in patients with diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med 325: 836–842, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai W, He JC, Zhu L, Chen X, Zheng F, Striker GE, Vlassara H: Oral glycotoxins determine the effects of calorie restriction on oxidant stress, age-related diseases, and lifespan. Am J Pathol 173: 327–336, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koschinsky T, He CJ, Mitsuhashi T, Bucala R, Liu C, Buenting C, Heitmann K, Vlassara H: Orally absorbed reactive glycation products (glycotoxins): An environmental risk factor in diabetic nephropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94: 6474–6479, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He C, Sabol J, Mitsuhashi T, Vlassara H: Dietary glycotoxins: Inhibition of reactive products by aminoguanidine facilitates renal clearance and reduces tissue sequestration. Diabetes 48: 1308–1315, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uribarri J, Cai W, Ramdas M, Goodman S, Pyzik R, Chen X, Zhu L, Striker GE, Vlassara H: Restriction of advanced glycation end products improves insulin resistance in human type 2 diabetes: Potential role of AGER1 and SIRT1. Diabetes Care 34: 1610–1616, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vlassara H, Striker GE: AGE restriction in diabetes mellitus: A paradigm shift. Nat Rev Endocrinol 7: 526–539, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward MS, Fortheringham AK, Cooper ME, Forbes JM: Targeting advanced glycation endproducts and mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol 13: 654–661, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vlassara H, Uribarri J, Cai W, Goodman S, Pyzik R, Post J, Grosjean F, Woodward M, Striker GE: Effects of sevelamer on HbA1c, inflammation, and advanced glycation end products in diabetic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 934–942, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perkovic V, Heerspink HL, Chalmers J, Woodward M, Jun M, Li Q, MacMahon S, Cooper ME, Hamet P, Marre M, Mogensen CE, Poulter N, Mancia G, Cass A, Patel A, Zoungas S, ADVANCE Collaborative Group : Intensive glucose control improves kidney outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int 83: 517–523, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doublier S, Lupia E, Catanuto P, Elliot SJ: Estrogens and progression of diabetic kidney damage. Curr Diabetes Rev 7: 28–34, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tuttle KR, Bakris GL, Bilous RW, Chiang JL, de Boer IH, Goldstein-Fuchs J, Hirsch IB, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Narva AS, Navaneethan SD, Neumiller JJ, Patel UD, Ratner RE, Whaley-Connell AT, Molitch ME: Diabetic kidney disease: A report from an ADA Consensus Conference. Diabetes Care 37: 2864–2883, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldberg T, Cai W, Peppa M, Dardaine V, Baliga BS, Uribarri J, Vlassara H: Advanced glycoxidation end products in commonly consumed foods. J Am Diet Assoc 104: 1287–1291, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uribarri J, Woodruff S, Goodman S, Cai W, Chen X, Pyzik R, Yong A, Striker GE, Vlassara H: Advanced glycation end products in foods and a practical guide to their reduction in the diet. J Am Diet Assoc 110: 911–, e12., 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waheed S, Matsushita K, Astor BC, Hoogeveen RC, Ballantyne C, Coresh J: Combined association of creatinine, albuminuria, and cystatin C with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular and kidney outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 434–442, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, Eckfeldt JH, Feldman HI, Greene T, Kusek JW, Manzi J, Van Lente F, Zhang YL, Coresh J, Levey AS, CKD-EPI Investigators : Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med 367: 20–29, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fan L, Levey AS, Gudnason V, Eiriksdottir G, Andresdottir MB, Gudmundsdottir H, Indridason OS, Palsson R, Mitchell G, Inker LA: Comparing GFR estimating equations using cystatin C and creatinine in elderly individuals [published online December 19, 2014]. J Am Soc Nephrol 10.1681/ASN.2014060607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vlassara H, Cai W, Goodman S, Pyzik R, Yong A, Chen X, Zhu L, Neade T, Beeri M, Silverman JM, Ferrucci L, Tansman L, Striker GE, Uribarri J: Protection against loss of innate defenses in adulthood by low advanced glycation end products (AGE) intake: Role of the antiinflammatory AGE receptor-1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94: 4483–4491, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bryc K, Durand EY, Macpherson JM, Reich D, Mountain JL: The Genetic Ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States. Am J Hum Genet 96: 37–53, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Block GA, Spiegel DM, Ehrlich J, Mehta R, Lindbergh J, Dreisbach A, Raggi P: Effects of sevelamer and calcium on coronary artery calcification in patients new to hemodialysis. Kidney Int 68: 1815–1824, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raggi P, Vukicevic S, Moysés RM, Wesseling K, Spiegel DM: Ten-year experience with sevelamer and calcium salts as phosphate binders. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5[Suppl 1]: S31–S40, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ketteler M, Rix M, Fan S, Pritchard N, Oestergaard O, Chasan-Taber S, Heaton J, Duggal A, Kalra PA: Efficacy and tolerability of sevelamer carbonate in hyperphosphatemic patients who have chronic kidney disease and are not on dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 1125–1130, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cai W, Uribarri J, Zhu L, Chen X, Swamy S, Zhao Z, Grosjean F, Simonaro C, Kuchel GA, Schnaider-Beeri M, Woodward M, Striker GE, Vlassara H: Oral glycotoxins are a modifiable cause of dementia and the metabolic syndrome in mice and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: 4940–4945, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Astor BC, Hallan SI, Miller ER, 3rd, Yeung E, Coresh J: Glomerular filtration rate, albuminuria, and risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in the US population. Am J Epidemiol 167: 1226–1234, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta J, Mitra N, Kanetsky PA, Devaney J, Wing MR, Reilly M, Shah VO, Balakrishnan VS, Guzman NJ, Girndt M, Periera BG, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Joffe MM, Raj DS, CRIC Study Investigators : Association between albuminuria, kidney function, and inflammatory biomarker profile in CKD in CRIC. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1938–1946, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niewczas MA, Gohda T, Skupien J, Smiles AM, Walker WH, Rosetti F, Cullere X, Eckfeldt JH, Doria A, Mayadas TN, Warram JH, Krolewski AS: Circulating TNF receptors 1 and 2 predict ESRD in type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 507–515, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vlassara H, Striker GE: Advanced glycation endproducts in diabetes and diabetic complications. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 42: 697–719, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vlassara H, Cai W, Chen X, Serrano EJ, Shobha MS, Uribarri J, Woodward M, Striker GE: Managing chronic inflammation in the aging diabetic patient with CKD by diet or sevelamer carbonate: A modern paradigm shift. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 67: 1410–1416, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng F, Zeng YJ, Plati AR, Elliot SJ, Berho M, Potier M, Striker LJ, Striker GE: Combined AGE inhibition and ACEi decreases the progression of established diabetic nephropathy in B6 db/db mice. Kidney Int 70: 507–514, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parsa A, Kao WH, Xie D, Astor BC, Li M, Hsu CY, Feldman HI, Parekh RS, Kusek JW, Greene TH, Fink JC, Anderson AH, Choi MJ, Wright JT, Jr, Lash JP, Freedman BI, Ojo A, Winkler CA, Raj DS, Kopp JB, He J, Jensvold NG, Tao K, Lipkowitz MS, Appel LJ, AASK Study Investigators. CRIC Study Investigators : APOL1 risk variants, race, and progression of chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 369: 2183–2196, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhalla V, Zhao B, Azar KM, Wang EJ, Choi S, Wong EC, Fortmann SP, Palaniappan LP: Racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of proteinuric and nonproteinuric diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes Care 36: 1215–1221, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.