Abstract

Hepatitis C virus is the only known RNA virus with an exclusively cytoplasmic life cycle that is associated with cancer. The mechanisms by which it causes cancer are unclear, but chronic immune-mediated inflammation and associated oxidative chromosomal DNA damage are likely to play a role. Nonetheless, compelling data suggest that the path to hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis C shares some important features with human papillomavirus-induced carcinogenesis. Interactions of viral proteins with key regulators of the cell cycle, the retinoblastoma susceptibility protein (Rb), p53, and possibly DDX5 and DDX3 lead to enhanced cellular proliferation and may also compromise multiple cell cycle checkpoints that act to maintain genomic integrity, thus setting the stage for carcinogenesis. Dysfunctional DNA damage and mitotic spindle checkpoints resulting from these viral-host interactions may promote chromosomal instability and leave the hepatocyte incapable of effectively controlling DNA damage arising from the effects of oxidative stress mediated by HCV proteins, alcohol, and immune-mediated inflammation.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, p53, retinoblastoma, cell cycle checkpoint, aneuploidy

INTRODUCTION

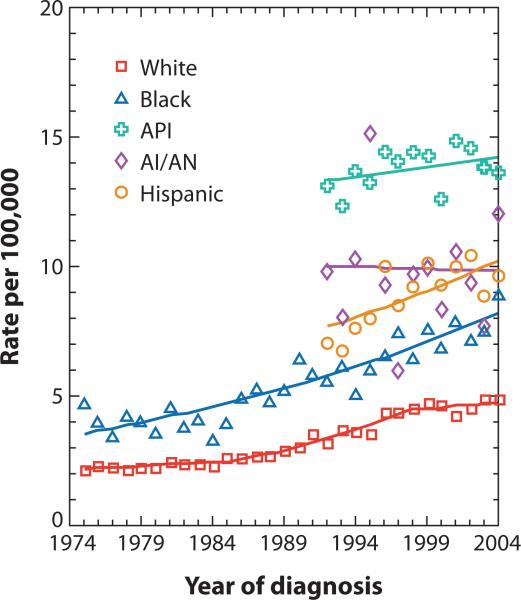

Worldwide, over 170 million people are estimated to be infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) (1), reflecting the unique capacity of this virus to establish long standing, persistent infections. Within the United States, HCV infection is the leading cause of chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis, and an increasingly important factor in the etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (2, 3, 4). Current treatment options are limited to interferon-based therapies, which are expensive, relatively toxic, and suboptimal, resulting in sustained viral clearance in only 40–50% of those infected with the most prevalent viral genotypes (5, 6). Interferon treatment has been suggested to lessen the risk of hepatocellular cancer (7, 8), but it is uncertain whether this is the case in the absence of a sustained antiviral response to therapy. Moreover, access to treatment is limited. Importantly, the incidence of liver cancer has increased dramatically over the past two decades (Fig. 1). The age-adjusted risk for HCV-related liver cancer increased 226% between 1993-1999 among Americans over 65 years of age, compared with only 67% for hepatitis B virus-associated cancer (9). Liver cancer is increasingly found in younger individuals, with African-American and Hispanic males at particularly high risk (Fig. 1). This disparity closely mirrors racial and gender differences in HCV infection prevalence (2).

Figure 1.

Incidence of liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancer by race/ethnicity from 1974-2004, as reported by the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program of the U.S. National Cancer Institute (API = Asian/Pacific Islanders; AI/AN = American Indians/Alaska Natives).

The preponderance of data, both from the U.S. as well as Japan, suggests that increases in the incidence of HCC observed over the past several decades are due to an expansion in the number of individuals who are infected chronically with HCV (10). Liver cancer typically develops only after several decades of infection, and often in the setting of cirrhosis, but the mechanisms underlying the progression of HCV infection to cancer remain ill defined. As a positive-strand RNA virus, most if not all events related to HCV replication are restricted to the cytoplasm (11) , and there is no potential for integration of the viral genome into host chromosomal DNA such as occurs with many other tumor viruses. Indirect mechanisms are thus likely to contribute to the development of carcinoma, including the presence of cirrhosis and longstanding hepatic inflammation with associated oxidative stress and the potential for DNA damage (12, 13, 14). However, strong evidence as outlined below suggests that the proteins expressed by HCV may be directly oncogenic. This review is focused on the role of these proteins in HCV-associated hepatic carcinogenesis, and in particular how multiple interactions between these viral proteins and host cell proteins with tumor suppressor properties may contribute to the development of liver cancer in patients with chronic hepatitis C.

HEPATITIS C VIRUS

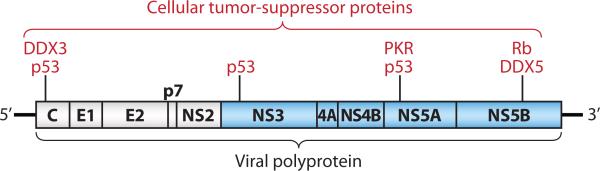

HCV is an enveloped, positive-strand RNA virus, classified within the genus Hepacivirus in the family Flaviviridae. Its 9.6-kb genome encodes a single, large polyprotein that is co- and post-translationally processed by cellular and viral proteases into at least 10 individual structural and nonstructural viral proteins (Fig. 2) (15, 16). Unlike cellular mRNAs that possess a cap structure at the 5’ end, translation of the viral RNA is mediated by an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) located within the 5'-untranslated region (UTR) (17, 18). Sequences in both the 5’-UTR and 3’-UTR are also essential for viral RNA replication (19, 20). Until very recently, no cultured cell type has been shown to be fully permissive for HCV replication. However, stable, G418-resistant cell lines have been successfully established following transfection of autonomously replicating dicistronic subgenomic and genome-length RNA replicons that express neomycin phosphotransferase (21, 22, 23). These cell lines express HCV proteins and faithfully recapitulate the molecular steps involved in viral RNA replication, but they do not produce infectious virus. HuH-7 cells, derived from a human hepatoma (24) have proven uniquely permissive for replication of these RNAs. In the past few years, several groups have shown that these cells, or their derivatives, are fully permissive for replication of certain strains of HCV, including a unique genotype 2a virus isolated from a patient with acute fulminant hepatitis C (a very rare disease) in Japan (25, 26), as well as a genotype 1a virus containing multiple cell culture-adaptive mutations (27). These virus systems have had a catalytic effect on the field, generating new knowledge of the molecular processes involved in the entry and release of virus from cells.

Figure 2.

Organization of the positive-strand RNA genome of HCV, showing the viral polyprotein (box) and individual mature viral proteins. Structural proteins are shown in white, and nonstructural proteins in blue, along with their interactions with cellular tumor suppressor proteins.

Proteins derived from the carboxy-terminal third of the viral polyprotein include the three structural proteins, core protein, which is a basic protein with RNA-binding activity that is thought to comprise the nucleocapsid of the virus, and two heavily glycosylated envelope proteins, E1 and E2 (Fig. 2). Downstream of these proteins are p7, a small transmembrane protein with ion channel activity, and NS2, a nonstructural protein that plays critical roles in polyprotein processing and viral assembly (27). The remaining nonstructural proteins expressed by HCV, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B (Fig. 2), are required for RNA replication (21). NS3 is a serine protease which is responsible for cis- or trans-cleavage at four sites within the HCV polyprotein, generating the amino-termini of NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B (28). NS3 also functions as an RNA helicase and NTPase, and is an essential component of the RNA replicase complex (29, 30). NS4A, a small 54-amino-acid protein forms a stable complex with amino-terminal third of NS3, the protease domain, and is required for full expression of serine protease activity (31). Importantly, the mature NS3/4A protease disrupts cellular signaling pathways leading to virus activation of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3), possibly contributing to the establishment of persistent infections (32, 33, 34). NS4B is an integral membrane protein, mostly localized on the cytoplasmic side of the ER membrane, and implicated in assembly of the replicase complex on lipid rafts (35, 36). NS5A, a phosphoprotein, plays a role in viral resistance to interferon (37, 38). NS5A also plays an ill-defined role in RNA replication, as adaptive mutations in NS5A are associated with increased replication efficiency of HCV replicons in hepatoma cells, and is also involved in virus assembly (22, 39). NS5B is the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and as the catalytic core of the macromolecular replicase complex, is essential for HCV RNA replication (40, 41, 42).

HCV is known to infect hepatocytes and HCV antigens can be found present within the cytoplasm of small numbers of hepatocytes in patients with chronic infection (43). It has also been suggested to be capable of replication in cells of lymphoid origin, but this remains controversial and not well proven to occur in vivo (44, 45).

HCV AND HEPATOCELLULAR CARCINOMA

Strong epidemiologic evidence links HCV infection to the development of hepatocellular cancer (10, 46). Globally, approximately 25% of HCC has been attributed to HCV infection, or about 155,000 deaths annually (47). HCV is associated with 80 % of HCC cases in Japan, far surpassing hepatitis B virus (HBV) as a risk factor in recent years (48). In the United States, the incidence of HCC is increasing rapidly, especially among disadvantaged African-Americans and Hispanics (Fig. 1) (49). In one recent U.S. series, 42% of patients with HCC had detectable HCV genomic RNA in liver tissue (50). As suggested above, chronic hepatic inflammation and oxidative stress, induced in part by mitochondrial injury associated with expression of the core protein of HCV, seems certain to contribute the pathogenesis of liver cancer due to HCV (13, 14). Studies have shown that the induction of a cellular immune response to HBV-associated antigens can lead to the development of liver cancer in HBV transgenic mice in which transgene expression is otherwise well tolerated (12). Similar immunopathologic mechanisms are likely to play a role in the development of liver cancer in patients with chronic inflammatory liver disease associated with HCV infection. Cirrhosis, the end product of the fibrosis induced by HCV infection, represents a preneoplastic stage in the development of liver cancer, typified by accelerated cycling of dysplastic hepatocytes (51). Nonetheless, compelling evidence indicates that HCV proteins may be intrinsically oncogenic, with their expression leading directly to HCC in the absence of an immune response, inflammation, or cirrhosis.

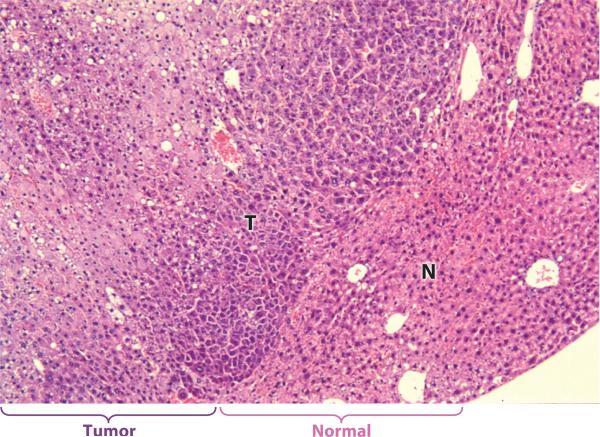

C57BL/6 mice transgenic for the HCV core gene and expressing a high abundance of this protein develop hepatic steatosis as well as HCC (52, 53). While liver cancer was not observed in core transgenic mouse lineages constructed in different genetic backgrounds (54, 55, 56), we also observed a significantly increased risk of hepatocellular cancer in transgenic mice expressing a low abundance of the entire polyprotein encoded by a Japanese genotype 1b virus (57, 58) (Fig. 3). There was neither hepatic inflammation nor fibrosis or cirrhosis, excluding these potential contributing factors in these mice. HCC occurred in 5 of 38 F0-F4 generation mice derived from this lineage, which was produced from a hybrid zygote obtained by a C3H/HeJ × C57BL/6 cross, but occurred less frequently in successive generations of these transgenic mice as they were bred against C57BL/6 (57). HCC occurred exclusively in male animals, and was increased in frequency either by iron loading or by co-expression of the HBV × protein (59, 60). Importantly, a related transgenic lineage expressing a substantially higher abundance of only the structural proteins from this virus (C, E1, E2, and p7) did not display an increased risk for cancer (57). Taken together, these data suggest a role for both the core protein as well as nonstructural proteins in HCV oncogenesis (53, 57). Consistent with the suggestion that nonstructural proteins may also contribute to carcinogenesis, the expression of NS3, NS5A, and NS5B all have been shown to have important interactions with host cell regulatory mechanisms in a variety of experimental settings. For example, NS3 and NS5A repress transcription of p21 by modulating the activity of p53 (61, 62, 63), while NS5A causes cell cycle perturbations by targeting cdk1/2-cyclin complexes (64). NS5B also inhibits cell proliferation in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle, independent of p53 expression (65).

Figure 3.

Well differentiated HCC (T) expanding into and compressing normal liver tissue (N) in an H&E stained section of liver from a 13 month old male FL-N/35 transgenic mouse expressing a low abundance of the entire HCV polyprotein (57).

In summary, although chronic infection with HCV is a major risk factor for HCC, there is considerable uncertainty about the mechanisms by which HCV infection leads to HCC. Chronic inflammation related to immune responses against infected cells is likely to play a role, with oxidative stress and resulting chromosomal DNA damage possibly contributing to carcinogenesis in this setting. However, HCV transgenic mice develop liver cancer in the absence of immunologic recognition of the transgene product, and with no preceding intrahepatic inflammation (53, 57). These data suggest a metabolic or genetic origin for HCV-associated HCC, and roles for both structural and nonstructural viral proteins in hepatocellular carcinogenesis. In the last few years, many previously unrecognized interactions of these proteins with the host cell have been revealed. The following section reviews the specific interactions of HCV proteins with key cellular tumor suppressors and explores how these interactions may promote carcinogenesis by causing hepatocellular proliferation and reduced effectiveness of cell cycle checkpoints.

INTERACTION OF VIRAL PROTEINS WITH TUMOR SUPPRESSORS

The p53 and Rb tumor suppressor proteins are frequently mutated in many cancers, including HCC. In viral infections that are associated with cancer, down-regulation of these key tumor suppressors, either by functional inactivation, as in the case of the simian virus 40 (SV40) T antigen interaction with p53, or by targeting the protein for degradation, as in the interaction of p53 with the E6 protein expressed by high-risk human papillomaviruses (HPVs). HPVs are double-stranded DNA viruses that are strongly implicated in the causation of cervical carcinoma (66, 67). Recent evidence suggesting that both p53 and Rb pathways may be dysregulated by HCV is reminiscent of the situation with HPV, in which two different proteins, E6 and E7, target these pathways in ways that are important to their oncogenic potential.

HCV interactions with the p53 pathway

Loss of function of the p53 tumor suppressor protein is frequently involved in hepatocellular carcinogenesis (68). HCV proteins have been shown to interact with p53 in several studies, as summarized in Table 1. The consequences of these interactions are not clear, but it is likely that the interactions affect the normal functions of p53. For example, while some studies have demonstrated that the core protein interacts with and enhances p53 transcriptional activity (69, 70), others have shown that p53-dependent transcription is either repressed or enhanced, depending upon levels of core expression (71). The NS3 protein also has been shown to interact with wt p53 when both proteins are transiently over-expressed in HeLa cells (72) and NS3 proteins from different HCV isolates were found to interact with p53 and inhibit p53-dependent transcription, with both the level of inhibition and the strength of the interaction with p53 depending upon the NS3 sequence (73).

TABLE 1.

Interactions of HCV proteins with the tumor suppressor p53.

| HCV protein interacting with p53 | Experimental System | Cell type | Observations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| core | Proteins expressed in vitro | Not applicable | Interaction detected by GST pulldown using in vitro translated proteins or by “far-western” blot using proteins expressed in bacteria. | (69) |

| core | Transient over-expression of core with GST-p53 fusions. | COS-7 | Interaction detected by GST pulldown. | (70) |

| core | Proteins expressed in vitro | Not applicable | Interaction detected by GST pulldown using in vitro translated proteins. | (71) |

| core | Transient over-expression with wt p53 | HepG2, HeLa | Co-localization of core and p53 detected by immunofluorescence analysis. | (71) |

| NS3 | Transient over-expression with wt p53 | HeLa, BHK-21 | Interaction detected by co-immunoprecipitation. | (72) |

| NS5A | Proteins expressed in vitro | Not applicable | Interaction detected by GST pulldown using in vitro translated NS5A and either p53 expressed from bacteria or HepG2 nuclear extracts. | (62) |

| NS5A | Transient over-expression | HepG2 | Interaction detected by co-immunoprecipitation or mammalian two-hybrid. Co-localization of NS5A and p53 detected by immunofluorescence . | (62) |

NS5A has been shown to interact with and sequester p53 at the perinuclear membrane when transiently expressed in HepG2 cells (62), in COS-7 cells or in the p53 negative cell line Hep3B when co-transfected with p53 (63). NS5A expression inhibited p53-activated transcription in reporter gene assays in the p53 wild-type cell lines HCT116 (74) and HepG2 cells (62, 75) as well as in p53 null Hep3B cells when co-transfected with wild type p53 (63). NS5A expression inhibited p53-mediated apoptosis in Hep3B cells (63) and promoted anchorage-independent growth in NIH3T3 cells (75). However, NS5A expressed from liver-specific promoters did not promote cancer in transgenic mice suggesting that NS5A is not intrinsically oncogenic (62).

Much of these data should be interpreted with caution because of their use of cell lines in which the p53 pathway may be abnormal, such as Huh7-derived cell lines in which p53 is mutated (76), or HeLa, COS-7 and NIH3T3 cells, where p53 activity is already modulated by viral proteins such as HPV E6 or the SV40 T antigen. This highlights a continuing difficulty in developing relevant experimental systems in the HCV field, as replication of the virus can be reproduced only in certain types of cultured cells, such as Huh-7 cells, which are derived from malignantly transformed hepatocytes.

HCV interactions with the Rb pathway

The Rb tumor suppressor plays a critical role in controlling cellular proliferation and apoptosis through its regulation of E2F transcription factors . It is targeted by oncoproteins expressed by several important DNA tumor viruses, but until recently has not been shown to be regulated by RNA viruses. A compelling body of data now suggests that HCV regulates the Rb pathway. Although no specific mechanism was suggested, Cho et al. (77) reported that conditional expression of the core protein resulted in a decreased half-life and reduced abundance of Rb in immortalized rat embryo fibroblasts, resulting in enhanced E2F transcription factor activity. Tsukiyama-Kohara et al. (78) described an initially positive, then negative effect on Rb activity following conditional expression of the complete HCV genome in HepG2 cells. After approximately 1.5 months in culture, cells expressing HCV RNA demonstrated increased anchorage independent growth, associated with enhanced cdk2 kinase activity, an increased abundance of phosphorylated Rb, and activation of E2F transcription factors.

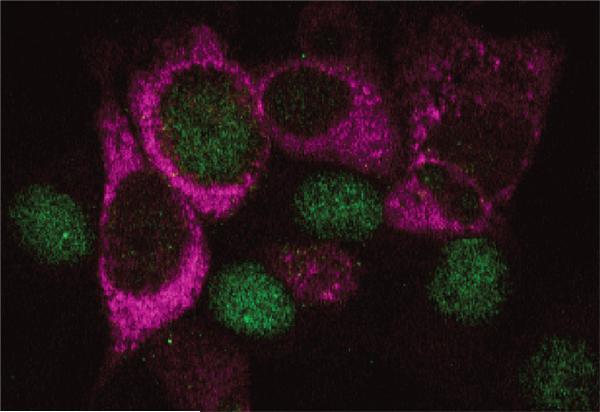

Other data derived from experimental systems that may be more physiologically relevant indicate that the abundance of Rb is significantly down-regulated in Huh7 cells supporting replication of HCV RNA (79, 80). Rb abundance is strongly down-regulated, and its normal nuclear localization altered to include a major cytoplasmic component, both in HCV replicon cells as well as in cultured hepatoma cells infected with either genotype 1a or 2a HCV (80) (Fig. 4). This occurs as a result of an interaction between the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, NS5B, and Rb (79). NS5B contains a conserved Leu-x-Cys/Asn-x-Asp motif that is homologous to Rb-binding domains in the oncoproteins of DNA viruses. This domain overlaps the polymerase active site, and mutations within it abrogate Rb binding and reverse the effects of NS5B on Rb abundance (79). NS5B-dependent down-regulation of Rb leads to both activation of E2F-dependent transcription, as well as increased cellular proliferation (79). Recent work in our laboratory has defined the underlying molecular mechanisms of Rb regulation by the HCV polymerase and shown that NS5B forms a cytoplasmic complex with Rb in infected cells (80). While Rb shows primarily nuclear and NS5B primarily cytoplasmic localization in normal cells, the ability of NS5B to form a complex with Rb may be facilitated by nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of Rb (81). Alternatively, NS5B may interact with Rb following its synthesis and prior to its transport to the nucleus. The E3 ubiquitin ligase, E6-associated protein (E6AP), is recruited to the NS5B-Rb complex, leading to NS5B-dependent ubiquitination of pRb and subsequent degradation of Rb via the proteasome. Thus, the decreased abundance of Rb observed in HCV replicon cells can be restored either by siRNA knockdown of E6AP, or by overexpression of a dominant-negative E6AP mutant (80). The disruption of Rb/E2F regulatory pathways in cells infected with HCV is likely to promote hepatocellular proliferation and chromosomal instability, as described in greater detail below, factors important for the development of liver cancer.

Figure 4.

Rb (green) and HCV antigen (red) expression in Huh-7.5 cells infected 96 hr previously with the JFH1 strain of HCV at a low multiplicity of infection. Cells infected with the virus show cytoplasmic viral antigen associated with depletion of nuclear Rb.

HCV and other emerging tumor suppressor functions

The previous sections show how the HCV core, NS3 and NS5A proteins all appear to interact with or modulate the activity of p53 (61, 62, 71), while NS5B, the viral polymerase, binds to Rb, targeting it for degradation and increasing the activity of E2F-responsive promoters (79, 80). The functional effects of these interactions may be enhanced by other interactions of HCV proteins with additional cellular tumor suppressor proteins, either by direct modulation of their activity or by sequestering them for the purpose of replicating the HCV genome. The core protein appears to sequester DDX3 (82), a cytoplasmic DExD/H helicase that is required for HCV RNA replication and recently recognized to have tumor suppressor properties (83, 84). In addition, the NS5B protein causes intracellular re-localization of DDX5 (a.k.a. p68) (85), another DExD/H helicase that acts as a transcriptional co-activator of p53 (86). The functional impact of this particular interaction is uncertain, but is the focus of current research in our laboratory.

HCV proteins also interact with and down-regulate a number of host proteins that contribute to cellular antiviral defenses but also have anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic functions. NS5A functionally represses the double-stranded RNA-activated kinase PKR (38, 87), a tumor protein that suppresses cellular proliferation and promotes apoptosis through its control of protein translation (88). The NS3/4A protease disrupts the pathways that control activation of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3) (32), yet another host protein with significant tumor suppressor properties. HCV proteins also modulate cellular signal transduction pathways that control growth and proliferation. For example, NS5A has been shown to interact with the phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulatory subunit p85 (89), resulting in activation of a signaling cascade that blocks apoptosis and leads to stabilization of the proto-oncogene β-catenin (90). β-catenin is a component of the Wnt pathway that is frequently deregulated in HCC (91). Another signal transduction pathway that is regulated by HCV is the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) pathway. The core protein interacts with Smad3, a component of the TGF-β pathway, disrupting signaling to inhibit the anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects of TGF-β (92, 93).

Functional importance of HCV interactions with tumor suppressors

Despite fundamental differences in the replication mechanisms and genome structures of HCV and HPVs, interesting parallels can be drawn between the interactions of HCV and HPV with these tumor suppressor pathways. HPVs rely on host DNA replication machinery in order to replicate their genomes. The HPV E6 and E7 proteins likely evolved interactions with the p53 and Rb regulators in order to disrupt normal cell cycle controls and stimulate expression of cellular genes required for viral replication (reviewed in 66). Similarly, there is good evidence that the synthesis of HCV RNA is increased during the S phase of the cell cycle, and that HCV RNA replication is enhanced in proliferating cells (94, 95). However, the cell cycle is normally tightly controlled in adult liver, in which the hepatocytes are typically quiescent. It is also important to note that interferon, produced by host cells in response to infection, can signal cells to arrest in the G1 phase (96, 97, 98, 99). This has likely resulted in evolutionary pressure for HCV, like HPV, to interact with and modulate the activity of cellular proteins that control proliferation.

The aggregate effect of the HCV-host interactions described above is likely to be enhanced proliferation of the hepatocyte, a cell type with a normally low rate of division, and disruption of pathways controlling apoptosis. However, as with the HPV E6 and E7 proteins in epithelial cells, these interactions may also impair the effectiveness of important cell cycle checkpoints. Strong evidence suggests that HPV E6 and E7 may promote cellular genomic instability, including structural chromosomal changes and numerical chromosomal imbalances, by abrogating specific cell cycle checkpoints (reviewed in 100). It seems likely that HCV infection may have similar effects on the hepatocyte.

DISRUPTION OF CELL CYCLE CHECKPOINT CONTROL AND VIRUS-INDUCED CHROMOSOMAL INSTABILITY

The transitions from G1 to S phase, and from G2 to mitosis, are normally delayed by checkpoints in response to DNA damage. These DNA damage checkpoints are critical controls in prevention of cancer, as they allow cells to repair chromosomal damage before DNA replication or cell division. Importantly, they require active p53 and Rb pathways (101, 102). Expression of the E6 and E7 proteins from high risk HPVs can over-ride DNA damage-induced G1 arrest (103). Furthermore, E6 proteins from high risk HPVs are also able to compromise the G2/M DNA damage checkpoint (104). Unlike E6 from high risk HPV, HCV proteins do not target p53 for degradation. However, as discussed above, HCV proteins have been shown to associate with p53, affecting its activity. The modulation of p53 activity by HCV proteins may have consequences for the cell similar to the effects of p53 modulation by the large T antigen of the polyoma virus SV40, another DNA tumor virus (105). T antigen interactions with p53 impair DNA damage checkpoints (106), allowing infected cells to continue through the cell cycle in the presence of DNA damage and thus leading to the accumulation of mutations.

Another cell cycle checkpoint, the mitotic spindle checkpoint (MSC), arrests mitotic cells at the metaphase-anaphase transition until the kinetochores of all sister chromosomes are occupied by microtubules attached to opposite poles of the spindle (reviewed in 107). The MSC prevents aneuploidy by ensuring the correct segregation of chromosomes before cytokinesis. The HPV E7 protein, which interacts with and inactivates Rb, thereby inducing cellular proliferation, also disrupts the MSC (108). Although the impact of E7 on the MSC may not be entirely dependent upon its ability to interact with Rb (109), Rb dysfunction alone can disrupt the MSC and promote aneuploidy (110). Down-regulation of Rb enhances expression of E2F-responsive genes, including Mad2, a protein involved in the MSC. Aberrant expression (knockout or overexpression) of Mad2 impairs the MSC, causing genomic instability and aneuploidy (111). The interaction of the HCV polymerase, NS5B, with Rb results in the degradation of Rb and activates the Mad2 promoter (79). Significantly, the integrity of Rb appears to be particularly important in the normally quiescent hepatocyte, as liver-specific loss of Rb has been shown to promote ectopic cell cycle entry and aberrant ploidy (112). Taken together, these data suggest that infection with HCV, like HPV, may lead to a loss of host cell genomic stability due to defects in the MSC, related to NS5B-mediated deregulation of the Rb pathway.

Disruption of the MSC and chromosomal mis-segregation during mitosis is likely to produce daughter cells containing gross chromosomal rearrangements and deletions. Lacking essential genes, such cells would have reduced viability. However, random chromosomal mis-segregation (such as might result from the NS5B-Rb interaction) has the potential to produce more subtle mutations, and occasionally, by chance, allow a daughter cell containing mutations in a tumor suppressor gene to survive and multiply. The acquisition of further mutations may allow these cells to proliferate, suppress apoptosis and acquire a selective growth advantage. Such a scenario is congruent with a “multi-hit” mechanism for HCV oncogenesis, and is consistent with the genetic heterogeneity that is evident in individual HCCs from different patients as well as the frequent presence of structural genomic changes (51).

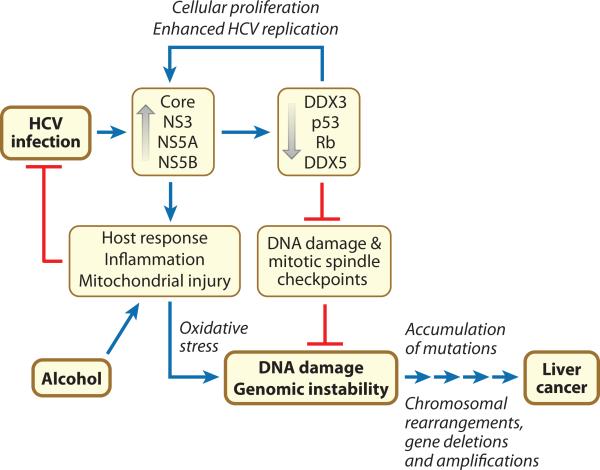

AN INTEGRATED MODEL FOR DEVELOPMENT OF HCV-ASSOCIATED HCC

Considered in the context of the inflammation that typically accompanies chronic hepatitis C, these recent findings suggest a model for development of HCV-associated HCC in which inflammation arising from infection promotes chromosomal DNA damage while specific interactions of viral proteins with key cell cycle regulators impair the capacity of the hepatocyte to recognize and properly respond to such DNA damage (Fig. 5). Viral replication is enhanced by interactions of multiple viral proteins with cellular regulators like Rb and DDX3 that promote proliferation of the hepatocyte. Immune recognition of the products of viral replication typically fails to eliminate the virus (11), but these host responses cause significant inflammation, promote accelerated cycling of infected hepatocytes, and result in the production of reactive oxygen species. Independent of inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction related directly to expression of the HCV core protein adds to this oxidative stress (113, 114). In a setting of increased cellular proliferation, this increases the risk of oxidative DNA damage. However, DNA damage checkpoints are compromised by viral modulation of Rb and p53 functions, allowing mutations to accumulate within proliferating hepatocytes. Deregulation of Mad2 expression due to NS5B-mediated down-regulation of Rb also impairs the MSC, and further promotes chromosomal instability. Viral modulation of p53 activity suppresses apoptotic pathways that normally respond to chromosomal mis-segregation and DNA damage, allowing aneuploid cells to survive. Indeed, mouse embryo fibroblasts in which both Mad2 and p53 are deleted are viable, but display a high level of chromosomal instability (115). The end result is an hepatocyte that has accumulated sufficient mutations and structural chromosome damage to no longer be capable of properly regulating its cell cycle, at which point the continuing influence of the viral proteins becomes irrelevant to its future.

Figure 5.

Hypothetical cellular pathways leading to liver cancer in persons who are chronically infected with HCV. See the text for details.

This is the point at which the HCV and HPV tumorigenesis models diverge, as malignant transformation by high-risk HPVs typically entails integration of the HPV genome segments encoding E6 and E7 and high level expression of these viral oncogenes (66). This is not the case with HCV, as the relevant viral proteins merely set the stage for cancer, promoting proliferation when expressed and preventing the actively infected cell from recognizing and responding appropriately to chromosomal damage.

This model, while speculative and in need of further proof, is attractive in that it accounts for the uniquely strong association between persistent HCV infection and liver cancer. It explains why cancer develops in the absence of hepatic inflammation in HCV transgenic animals, and why HCV RNA is not always present in malignant cells. It is consistent with the multi-step progression of dysplastic hepatocytes to carcinoma, and the wide variety of structural genetic defects that have been observed in individual HCCs (51). With malignant transformation, the hepatocyte may lose its ability to support HCV replication due to the loss of expression of one or more essential host factors. HepG2 cells, for example, are human hepatoma cells that are non-permissive for HCV infection because they do not express CD81, an essential factor for viral entry that is expressed by normal hepatocytes (26). Because there is no chromosomal integration of the HCV genome, all traces of the virus could be lost from a malignant cell clone under such circumstances. This hypothesis also explains the slow and uncertain progression to cancer in the typical patient with hepatitis C, and why the risk of cancer is significantly increased by regular ingestion of even small amounts of alcohol (49). Alcohol adds to the mitochondrial injury, exacerbates oxidative stress, and promotes DNA damage in the face of damage response pathways impaired by viral proteins (116).

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

In the absence of an animal model in which HCV infection leads to cancer, proof for this hypothesis will not be secured easily. However, one can ask whether the rate of hepatocellular proliferation is increased in chronic hepatitis C, and, in particular, whether mitosis occurs more frequently in HCV-infected cells. Such measurements are complicated, however, by strong interferon responses induced during chronic hepatitis C, and the ability of type 1 interferons to suppress cellular proliferation (97, 98, 99). Nonetheless, a case-control study suggested that an increased frequency of hepatocytes staining positively for Ki-67, a marker of hepatocyte proliferation, precedes the development of HCC in chronic hepatitis C (117). However, it will be important to determine whether the cells that are proliferating are those that are actively infected with HCV. Such data would confirm the biological relevance of the laboratory observations described above. Recent advances in imaging, including multi-photon microscopy and the use of quantum dot probes, coupled with laser-capture microdissection and microarray analyses, should permit quantitative single cell analyses of the relationship between HCV proteins, hepatocellular proliferation, and the status of Rb, DDX3, DDX5 and possibly p53.

It will also be important to determine whether HCV proteins that interfere with the Rb or p53 pathways abrogate specific cell cycle checkpoints, as the HPV E6 and E7 proteins do (103, 104, 106, 108). Cells bearing autonomously replicating subgenomic HCV replicons (21) have provided a great deal of information on molecular aspects of HCV RNA replication. In addition, recent successes in propagating the virus in cell culture (25, 26, 27) are providing new opportunities for examining the interaction of HCV proteins with cellular pathways in in vitro infection models. Most of these replication and infection models utilize Huh7 cells, a human hepatoma cell line that expresses an over-abundance of a mutant p53 (76). While the malignant origin of these cells precludes definitive studies of the impact of HCV infection on cell cycle regulation and checkpoint functionality, continuing progress in this field will almost certainly provide additional permissive cell substrates in which these questions can be addressed. Recent studies have shown that NS5A over-expression can lead to chromosomal instability by disruption of a mitotic checkpoint (118). However, these studies used cells that express mutant p53 (Huh7 cells) or that contain HPV genomes (Chang liver cells). A critical question will be whether the interactions of HCV proteins with Rb and p53 affect cell cycle checkpoints in cells with normal ploidy and intact cell cycle regulation. Such studies are likely to provide valuable insight into mechanisms of hepatocellular carcinogenesis in chronic hepatitis C. Moreover, they may point toward new strategies for the treatment HCV infection and the prevention of HCV-associated HCC.

SUMMARY POINTS.

HCV-associated liver cancer typically develops after decades of infection within a background of cirrhosis and chronic inflammation.

Chronic inflammation related to immune responses to viral proteins promotes hepatocyte destruction and regeneration, disturbs the normal homeostasis of the liver, and likely contributes to cancer, but the occurrence of HCC in HCV transgenic mice suggests that HCV proteins are also intrinsically oncogenic.

Multiple HCV-encoded proteins interact with and modulate the activity of host cell tumor suppressors and regulatory proteins that control apoptosis and cell proliferation.

The interactions of HCV proteins with host tumor suppressor proteins such as Rb and p53 may lead to defects in key cell cycle checkpoints that act to maintain the integrity of the host genome.

HCV-associated carcinogenesis is a multi-step process in which virus-induced defects in regulation of the cell cycle and associated mitotic checkpoints are likely to compound the effects of host DNA damage resulting from oxidative stress induced by HCV proteins and immune-mediated inflammation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (U19-AI40035) and a Jeanne B. Kempner Postdoctoral Fellowship to DRM. The authors are grateful to Drs. Steven A. Weinman, Cornelis J. Elferink, and Shu-Yuan Xiao for helpful discussions and Ms. Yuqiong Liang for expert technical assistance.

Abbreviations/acronyms

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- MSC

mitotic spindle checkpoint

- Rb

retinoblastoma susceptibility protein

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Global burden of disease (GBD) for hepatitis C J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2004;44:20–9. doi: 10.1177/0091270003258669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alter MJ, Kruszon-Moran D, Nainan OV, McQuillan GM, Gao F, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1988 through 1994. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;341:556–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908193410802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma: recent trends in the United States. Gastro. 2004;127:S27–S34. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vong S, Bell BP. Chronic liver disease mortality in the United States, 1990-1998. Hepatology. 2004;39:476–83. doi: 10.1002/hep.20049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis GL, Esteban-Mur R, Rustgi V, Hoefs J, Gordon SC, et al. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin for the treatment of relapse of chronic hepatitis C. International Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group [see comments]. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;339:1493–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811193392102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McHutchison JG, Fried MW. Current therapy for hepatitis C: pegylated interferon and ribavirin. Clin. Liver Dis. 2003;7:149–61. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(02)00077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishiguchi S, Kuroki T, Nakatani S, Morimoto H, Takeda T, et al. Randomised trial of effects of interferon-α on incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic active hepatitis C with cirrhosis. Lancet. 1995;346:1051–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91739-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazzella G, Accogli E, Sottili S, Festi D, Orsini M, et al. Alpha interferon treatment may prevent hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV-related liver cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 1996;24:141–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(96)80022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davila JA, Morgan RO, Shaib Y, McGlynn KA, El Serag HB. Hepatitis C infection and the increasing incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma: a population-based study. Gastro. 2004;127:1372–80. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiyosawa K, Umemura T, Ichijo T, Matsumoto A, Yoshizawa K, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: recent trends in Japan. Gastro. 2004;127:S17–S26. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lemon SM, Walker C, Alter MJ, Yi M. Hepatitis C viruses. In: Knipe D, Howley P, Griffin DE, Martin MA, Lamb RA, et al., editors. Fields Virology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2007. pp. 1253–1304. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamoto Y, Guidotti LG, Kuhlen CV, Fowler P, Chisari FV. Immune pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp. Med. 1998;188:341–50. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartsch H, Nair J. Oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation-derived DNA-lesions in inflammation driven carcinogenesis. Cancer Detect. Prev. 2004;28:385–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okuda M, Li K, Beard MR, Showalter LA, Scholle F, et al. Mitochondrial injury, oxidative stress, and antioxidant gene expression are induced by hepatitis C virus core protein. Gastro. 2002;122:366–75. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.30983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pawlotsky JM. Pathophysiology of hepatitis C virus infection and related liver disease. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindenbach BD, Rice CM. Molecular biology of flaviviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 2003;59:23–61. 23–61. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(03)59002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rijnbrand RC, Lemon SM. Internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation in hepatitis C virus replication. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2000;242:85–116. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-59605-6_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsukiyama-Kohara K, Iizuka N, Kohara M, Nomoto A. Internal ribosome entry site within hepatitis C virus RNA. J. Virol. 1992;66:1476–83. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1476-1483.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friebe P, Lohmann V, Krieger N, Bartenschlager R. Sequences in the 5' nontranslated region of hepatitis C virus required for RNA replication. J Virol. 2001;75:12047–57. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.24.12047-12057.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yi M, Lemon SM. 3' nontranslated RNA signals required for replication of hepatitis C virus RNA. J Virol. 2003;77:3557–68. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.6.3557-3568.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lohmann V, Korner F, Koch J, Herian U, Theilmann L, Bartenschlager R. Replication of subgenomic hepatitis C virus RNAs in a hepatoma cell line. Science. 1999;285:110–3. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5424.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blight KJ, Kolykhalov AA, Rice CM. Efficient initiation of HCV RNA replication in cell culture. Science. 2000;290:1972–4. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5498.1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ikeda M, Yi M, Li K, Lemon SM. Selectable subgenomic and genome-length dicistronic RNAs derived from an infectious molecular clone of the HCV-N strain of hepatitis C virus replicate efficiently in cultured Huh7 cells. J Virol. 2002;76:2997–3006. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.6.2997-3006.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakabayashi H, Taketa K, Miyano K, Yamane T, Sato J. Growth of human hepatoma cells lines with differentiated functions in chemically defined medium. Cancer Res. 1982;42:3858–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wakita T, Pietschmann T, Kato T, Date T, Miyamoto M, et al. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nature Med. 2005;11:791–6. doi: 10.1038/nm1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindenbach BD, Evans MJ, Syder AJ, Wolk B, Tellinghuisen TL, et al. Complete replication of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. Science. 2005;309:623–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1114016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yi M, Villanueva RA, Thomas DL, Wakita T, Lemon SM. Production of infectious genotype 1a hepatitis C virus (Hutchinson strain) in cultured human hepatoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:2310–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510727103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tomei L, Failla C, Santolini E, De Francesco R, La Monica N. NS3 is a serine protease required for processing of hepatitis C virus polyprotein. J. Virol. 1993;67:4017–26. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4017-4026.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzich JA, Tamura JK, Palmer-Hill F, Warrener P, Grakoui A, et al. Hepatitis C virus NS3 protein polynucleotide-stimulated nucleoside triphosphatase and comparison with the related pestivirus and flavivirus enzymes. J Virol. 1993;67:6152–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6152-6158.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gosert R, Egger D, Lohmann V, Bartenschlager R, Blum HE, et al. Identification of the hepatitis C virus RNA replication complex in Huh-7 cells harboring subgenomic replicons. J. Virol. 2003;77:5487–92. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.9.5487-5492.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin C, Thomson JA, Rice CM. A central region in the hepatitis C virus NS4A protein allows formation of an active NS3-NS4A serine proteinase complex in vivo and in vitro. J. Virol. 1995;69:4373–80. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4373-4380.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foy E, Li K, Wang C, Sumter R, Ikeda M, et al. Regulation of interferon regulatory factor-3 by the hepatitis C virus serine protease. Science. 2003;300:1145–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1082604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li K, Foy E, Ferreon JC, Nakamura M, Ferreon ACM, et al. Immune evasion by hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease-mediated cleavage of the TLR3 adaptor protein TRIF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:2992–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408824102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meylan E, Curran J, Hofmann K, Moradpour D, Binder M, et al. Cardif is an adaptor protein in the RIG-I antiviral pathway and is targeted by hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2005;437:1167–72. doi: 10.1038/nature04193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao L, Aizaki H, He JW, Lai MM. Interactions between viral nonstructural proteins and host protein hVAP-33 mediate the formation of hepatitis C virus RNA replication complex on lipid raft. J Virol. 2004;78:3480–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3480-3488.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hugle T, Fehrmann F, Bieck E, Kohara M, Krausslich HG, et al. The hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 4B is an integral endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein. Virology. 2001;284:70–81. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Enomoto N, Sakuma I, Asahina Y, Kurosaki M, Murakami T, et al. Interferon sensitivity determining sequence of the hepatitis C virus genome. Hepatology. 1996;24:460. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1996.v24.ajhep0240460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gale MJ, Jr., Korth MJ, Tang NM, Tan SL, Hopkins DA, et al. Evidence that hepatitis C virus resistance to interferon is mediated through repression of the PKR protein kinase by the nonstructural 5A protein. Virology. 1997;230:217–27. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyanari Y, Atsuzawa K, Usuda N, Watashi K, Hishiki T, et al. The lipid droplet is an important organelle for hepatitis C virus production. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:1089–97. doi: 10.1038/ncb1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Behrens SE, Tomei L, De Francesco R. Identification and properties of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of hepatitis C virus. EMBO J. 1996;15:12–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kolykhalov AA, Mihalik K, Feinstone SM, Rice CM. Hepatitis C virus-encoded enzymatic activities and conserved RNA elements in the 3' nontranslated region are essential for virus replication in vivo. J. Virol. 2000;74:2046–51. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.4.2046-2051.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lohmann V, Roos A, Korner F, Koch JO, Bartenschlager R. Biochemical and kinetic analyses of NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of the hepatitis C virus. Virology. 1998;249:108–18. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lau DT, Fish PM, Sinha M, Owen DM, Lemon SM, Gale M., Jr Patterns of IRF-3 activation, hepatic interferon-stimulated gene expression and immune cell infiltration in patients with chronic hepatitis C . Hepatology. 2008 doi: 10.1002/hep.22076. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sung VM, Shimodaira S, Doughty AL, Picchio GR, Can H, et al. Establishment of B-cell lymphoma cell lines persistently infected with hepatitis C virus in vivo and in vitro: the apoptotic effects of virus infection. J Virol. 2003;77:2134–46. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.3.2134-2146.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimizu YK, Igarashi H, Kiyohara T, Shapiro M, Wong DC, et al. Infection of a chimpanzee with hepatitis C virus grown in cell culture. J. Gen. Virol. 1998;79:1383–6. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-6-1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bosch FX, Ribes J, Cleries R, Diaz M. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Liver Dis. 2005;9:191–211. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perz JF, Armstrong GL, Farrington LA, Hutin YJ, Bell BP. The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide. J Hepatol. 2006;45:529–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshizawa H. Hepatocellular carcinoma associated with hepatitis C virus infection in Japan: projection to other countries in the foreseeable future. Oncology. 2002;62(Suppl 1):8–17. doi: 10.1159/000048270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seeff LB, Hoofnagle JH. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in areas of low hepatitis B and hepatitis C endemicity. Oncogene. 2006;25:3771–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abe K, Edamoto Y, Park YN, Nomura AM, Taltavull TC, et al. In situ detection of hepatitis B, C, and G virus nucleic acids in human hepatocellular carcinoma tissues from different geographic regions. Hepatology. 1998;28:568–72. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thorgeirsson SS, Grisham JW. Molecular pathogenesis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Genet. 2002;31:339–46. doi: 10.1038/ng0802-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moriya K, Nakagawa K, Santa T, Shintani Y, Fujie H, et al. Oxidative stress in the absence of inflammation in a mouse model for hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4365–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moriya K, Fujie H, Shintani Y, Yotsuyanagi H, Tsutsumi T, et al. The core protein of hepatitis C virus induces hepatocellular carcinoma in transgenic mice. Nat. Med. 1998;4:1065–7. doi: 10.1038/2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kawamura T, Furusaka A, Koziel MJ, Chung RT, Wang TC, et al. Transgenic expression of hepatitis C virus structural proteins in the mouse. Hepatology. 1997;25:1014–21. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pasquinelli C, Shoenberger JM, Chung J, Chang KM, Guidotti LG, et al. Hepatitis C virus core and E2 protein expression in transgenic mice. Hepatology. 1997;25:719–27. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wakita T, Taya C, Katsume A, Kato J, Yonekawa H, et al. Efficient conditional transgene expression in hepatitis C virus cDNA transgenic mice mediated by the Cre/loxP system. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:9001–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.9001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lerat H, Honda M, Beard MR, Loesch K, Sun J, et al. Steatosis and liver cancer in transgenic mice expressing the structural and nonstructural proteins of hepatitis C virus. Gastro. 2002;122:352–65. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.31001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lemon SM, Lerat H, Weinman SA, Honda M. A transgenic mouse model of steatosis and hepatocellular carcinoma associated with chronic hepatitis C virus infection in humans. Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 2000;111:146–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Furutani T, Hino K, Okuda M, Gondo T, Nishina S, et al. Hepatic iron overload induces hepatocellular carcinoma in transgenic mice expressing the hepatitis C virus polyprotein. Gastro. 2006;130:2087–98. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keasler VV, Lerat H, Madden CR, Finegold MJ, McGarvey MJ, et al. Increased liver pathology in hepatitis C virus transgenic mice expressing the hepatitis B virus X protein. Virology. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kwun HJ, Jung EY, Ahn JY, Lee MN, Jang KL. p53-dependent transcriptional repression of p21(waf1) by hepatitis C virus NS3. J Gen. Virol. 2001;82:2235–41. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-9-2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Majumder M, Ghosh AK, Steele R, Ray R, Ray RB. Hepatitis C virus NS5A physically associates with p53 and regulates p21/waf1 gene expression in a p53-dependent manner. J Virol. 2001;75:1401–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.3.1401-1407.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lan KH, Sheu ML, Hwang SJ, Yen SH, Chen SY, et al. HCV NS5A interacts with p53 and inhibits p53-mediated apoptosis. Oncogene. 2002;21:4801–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arima N, Kao CY, Licht T, Padmanabhan R, Sasaguri Y, Padmanabhan R. Modulation of cell growth by the hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein NS5A. J Biol. Chem. 2001;276:12675–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008329200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Siavoshian S, Abraham JD, Kieny MP, Schuster C. HCV core, NS3, NS5A and NS5B proteins modulate cell proliferation independently from p53 expression in hepatocarcinoma cell lines. Arch. Virol. 2004;149:323–36. doi: 10.1007/s00705-003-0205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hebner CM, Laimins LA. Human papillomaviruses: basic mechanisms of pathogenesis and oncogenicity. Rev. Med. Virol. 2006;16:83–97. doi: 10.1002/rmv.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Munger K, Baldwin A, Edwards KM, Hayakawa H, Nguyen CL, et al. Mechanisms of human papillomavirus-induced oncogenesis. J Virol. 2004;78:11451–60. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.11451-11460.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hussain SP, Schwank J, Staib F, Wang XW, Harris CC. TP53 mutations and hepatocellular carcinoma: insights into the etiology and pathogenesis of liver cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:2166–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lu W, Lo SY, Chen M, Wu K, Fung YK, Ou JH. Activation of p53 tumor suppressor by hepatitis C virus core protein. Virology. 1999;264:134–41. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Otsuka M, Kato N, Lan K, Yoshida H, Kato J, et al. Hepatitis C virus core protein enhances p53 function through augmentation of DNA binding affinity and transcriptional ability. J Biol. Chem. 2000;275:34122–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000578200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kao CF, Chen SY, Chen JY, Wu Lee YH. Modulation of p53 transcription regulatory activity and post-translational modification by hepatitis C virus core protein. Oncogene. 2004;23:2472–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ishido S, Hotta H. Complex formation of the nonstructural protein 3 of hepatitis C virus with the p53 tumor suppressor. FEBS Lett. 1998;438:258–62. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01312-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Deng L, Nagano-Fujii M, Tanaka M, Nomura-Takigawa Y, Ikeda M, et al. NS3 protein of Hepatitis C virus associates with the tumour suppressor p53 and inhibits its function in an NS3 sequence-dependent manner. J Gen. Virol. 2006;87:1703–13. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81735-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Qadri I, Iwahashi M, Simon F. Hepatitis C virus NS5A protein binds TBP and p53, inhibiting their DNA binding and p53 interactions with TBP and ERCC3. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1592:193–204. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ghosh AK, Steele R, Meyer K, Ray R, Ray RB. Hepatitis C virus NS5A protein modulates cell cycle regulatory genes and promotes cell growth. J. Gen. Virol. 1999;80:1179–83. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-5-1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bressac B, Galvin KM, Liang TJ, Isselbacher KJ, Wands JR, Ozturk M. Abnormal structure and expression of p53 gene in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U. S. A. 1990;87:1973–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cho J, Baek W, Yang S, Chang J, Sung YC, Suh M. HCV core protein modulates Rb pathway through pRb down-regulation and E2F-1 up-regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1538:59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(00)00137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tsukiyama-Kohara K, Tone S, Maruyama I, Inoue K, Katsume A, et al. Activation of the CKI-CDK-Rb-E2F pathway in full genome hepatitis C virus-expressing cells. J Biol. Chem. 2004;279:14531–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312822200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Munakata T, Nakamura M, Liang Y, Li K, Lemon SM. Down-regulation of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor by the hepatitis C virus NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:18159–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505605102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Munakata T, Liang Y, Kim S, McGivern DR, Huibregtse JM, et al. Hepatitis C virus induces E6AP-dependent degradation of the retinoblastoma protein. PLoS. Pathog. 2007;3:1335–47. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jiao W, Datta J, Lin HM, Dundr M, Rane SG. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein via Cdk phosphorylation-dependent nuclear export. J Biol. Chem. 2006;281:38098–108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605271200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Owsianka AM, Patel AH. Hepatitis C virus core protein interacts with a human DEAD box protein DDX3. Virology. 1999;257:330–40. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chang PC, Chi CW, Chau GY, Li FY, Tsai YH, et al. DDX3, a DEAD box RNA helicase, is deregulated in hepatitis virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma and is involved in cell growth control. Oncogene. 2006;25:1991–2003. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ariumi Y, Kuroki M, Abe K, Dansako H, Ikeda M, et al. DDX3 DEAD-box RNA helicase is required for hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J. Virol. 2007;81:13922–6. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01517-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Goh PY, Tan YJ, Lim SP, Tan YH, Lim SG, et al. Cellular RNA helicase p68 relocalization and interaction with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS5B protein and the potential role of p68 in HCV RNA replication. J Virol. 2004;78:5288–98. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5288-5298.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bates GJ, Nicol SM, Wilson BJ, Jacobs AM, Bourdon JC, et al. The DEAD box protein p68: a novel transcriptional coactivator of the p53 tumour suppressor. EMBO J. 2005;24:543–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gale M, Jr., Kwieciszewski B, Dossett M, Nakao H, Katze MG. Antiapoptotic and oncogenic potentials of hepatitis C virus are linked to interferon resistance by viral repression of the PKR protein kinase. J. Virol. 1999;73:6506–16. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6506-6516.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sadler AJ, Williams BR. Structure and function of the protein kinase R. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2007;316:253–92. 253–92. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-71329-6_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Street A, Macdonald A, Crowder K, Harris M. The Hepatitis C virus NS5A protein activates a phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent survival signaling cascade. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:12232–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312245200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Street A, Macdonald A, McCormick C, Harris M. Hepatitis C virus NS5A-mediated activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase results in stabilization of cellular beta-catenin and stimulation of beta-catenin-responsive transcription. J Virol. 2005;79:5006–16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.8.5006-5016.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.de La Coste A, Romagnolo B, Billuart P, Renard CA, Buendia MA, et al. Somatic mutations of the beta-catenin gene are frequent in mouse and human hepatocellular carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U. S. A. 1998;95:8847–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cheng PL, Chang MH, Chao CH, Lee YH. Hepatitis C viral proteins interact with Smad3 and differentially regulate TGF-beta/Smad3-mediated transcriptional activation. Oncogene. 2004;23:7821–38. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pavio N, Battaglia S, Boucreux D, Arnulf B, Sobesky R, et al. Hepatitis C virus core variants isolated from liver tumor but not from adjacent non-tumor tissue interact with Smad3 and inhibit the TGF-beta pathway. Oncogene. 2005;24:6119–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Scholle F, Li K, Bodola F, Ikeda M, Luxon BA, Lemon SM. Virus-host cell interactions during hepatitis C virus RNA replication: impact of polyprotein expression on the cellular transcriptome and cell cycle association with viral RNA synthesis. J Virol. 2004;78:1513–24. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1513-1524.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pietschmann T, Lohmann V, Rutter G, Kurpanek K, Bartenschlager R. Characterization of cell lines carrying self-replicating hepatitis C virus RNAs. J. Virol. 2001;75:1252–64. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.3.1252-1264.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Thomas NS, Burke LC, Bybee A, Linch DC. The phosphorylation state of the retinoblastoma (RB) protein in G0/G1 is dependent on growth status. Oncogene. 1991;6:317–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Burke LC, Bybee A, Thomas NS. The retinoblastoma protein is partially phosphorylated during early G1 in cycling cells but not in G1 cells arrested with alpha-interferon. Oncogene. 1992;7:783–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chin YE, Kitagawa M, Su WC, You ZH, Iwamoto Y, Fu XY. Cell growth arrest and induction of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 WAF1/CIP1 mediated by STAT1. Science. 1996;272:719–22. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5262.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tiefenbrun N, Melamed D, Levy N, Resnitzky D, Hoffman I, et al. Alpha interferon suppresses the cyclin D3 and cdc25A genes, leading to a reversible G0-like arrest. Mol. Cell Biol. 1996;16:3934–44. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Duensing S, Munger K. Mechanisms of genomic instability in human cancer: insights from studies with human papillomavirus oncoproteins. Int. J Cancer. 2004;109:157–62. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Agarwal ML, Agarwal A, Taylor WR, Stark GR. p53 controls both the G2/M and the G1 cell cycle checkpoints and mediates reversible growth arrest in human fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U. S. A. 1995;92:8493–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Harrington EA, Bruce JL, Harlow E, Dyson N. pRB plays an essential role in cell cycle arrest induced by DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U. S. A. 1998;95:11945–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Demers GW, Foster SA, Halbert CL, Galloway DA. Growth arrest by induction of p53 in DNA damaged keratinocytes is bypassed by human papillomavirus 16 E7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U. S. A. 1994;91:4382–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Thompson DA, Belinsky G, Chang TH, Jones DL, Schlegel R, Munger K. The human papillomavirus-16 E6 oncoprotein decreases the vigilance of mitotic checkpoints. Oncogene. 1997;15:3025–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Deppert W, Steinmayer T, Richter W. Cooperation of SV40 large T antigen and the cellular protein p53 in maintenance of cell transformation. Oncogene. 1989;4:1103–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chang TH, Ray FA, Thompson DA, Schlegel R. Disregulation of mitotic checkpoints and regulatory proteins following acute expression of SV40 large T antigen in diploid human cells. Oncogene. 1997;14:2383–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kops GJ, Weaver BA, Cleveland DW. On the road to cancer: aneuploidy and the mitotic checkpoint. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:773–85. doi: 10.1038/nrc1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Thomas JT, Laimins LA. Human papillomavirus oncoproteins E6 and E7 independently abrogate the mitotic spindle checkpoint. J Virol. 1998;72:1131–7. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1131-1137.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Duensing S, Munger K. Human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein can induce abnormal centrosome duplication through a mechanism independent of inactivation of retinoblastoma protein family members. J Virol. 2003;77:12331–5. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.22.12331-12335.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lentini L, Pipitone L, Di LA. Functional inactivation of pRB results in aneuploid mammalian cells after release from a mitotic block. Neoplasia. 2002;4:380–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hernando E, Nahle Z, Juan G, Diaz-Rodriguez E, Alaminos M, et al. Rb inactivation promotes genomic instability by uncoupling cell cycle progression from mitotic control. Nature. 2004;430:797–802. doi: 10.1038/nature02820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mayhew CN, Bosco EE, Fox SR, Okaya T, Tarapore P, et al. Liver-specific pRB loss results in ectopic cell cycle entry and aberrant ploidy. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4568–77. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Korenaga M, Wang T, Li Y, Showalter LA, Chan T, et al. Hepatitis C virus core protein inhibits mitochondrial electron transport and increases reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. J Biol. Chem. 2005;280:37481–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506412200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wang T, Weinman SA. Causes and consequences of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation in hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006;21(Suppl 3):S34–7. S34–S37. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Burds AA, Lutum AS, Sorger PK. Generating chromosome instability through the simultaneous deletion of Mad2 and p53. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U. S. A. 2005;102:11296–301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505053102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Otani K, Korenaga M, Beard MR, Li K, Qian T, et al. Hepatitis C virus core protein, cytochrome P450 2E1, and alcohol produce combined mitochondrial injury and cytotoxicity in hepatoma cells. Gastro. 2005;128:96–107. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Dutta U, Kench J, Byth K, Khan MH, Lin R, et al. Hepatocellular proliferation and development of hepatocellular carcinoma: a case-control study in chronic hepatitis C. Hum. Pathol. 1998;29:1279–84. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90257-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Baek KH, Park HY, Kang CM, Kim SJ, Jeong SJ, et al. Overexpression of hepatitis C virus NS5A protein induces chromosome instability via mitotic cell cycle dysregulation. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;359:22–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]