Abstract

Over the last decade, it has become clear that the role of angiotensin II extends far beyond recognized renal and cardiovascular effects. The presence of an autologous renin-angiotensin system has been demonstrated in almost all tissues of the body. It is now known that angiotensin II acts both independently and in synergy with TGF-beta to induce fibrosis via the angiotensin type 1 receptor (AT1) in a multitude of tissues outside of the cardiovascular and renal systems, including pulmonary fibrosis, intra-abdominal fibrosis, and systemic sclerosis. Interestingly, recent studies have described a paradoxically regenerative effect of the angiotensin system via stimulation of the angiotensin type 2 receptor (AT2). Activation of AT2 has been shown to ameliorate fibrosis in animal models of skeletal muscle, gastrointestinal, and neurologic diseases. Clinical reports suggest a beneficial role for modulation of angiotensin II signaling in cutaneous scarring. This article reviews current knowledge on the role that angiotensin II plays in tissue fibrosis, as well as current and potential therapies targeting this system.

Review

Angiotensin II (AngII) has long been recognized as the principal vasoactive mediator of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS). Over the past 20 years, however, it has become clear that effects of AngII extend beyond systemic cardiovascular and renal actions. Once believed to act only as a circulating hormone, it is now evident that a local ‘tissue RAS’ exists in almost all organs and tissues, including the heart [1], blood vessels [2], brain [2], kidney [2], fat [3], liver [4], and skin [5]. Tissue RASs are functionally autonomous systems that have been shown to play an important role in the development of fibrosis [6,7]. The following is a review of the role of AngII in fibrotic disorders, from cellular signaling to clinical correlation, and potential therapies aimed at modulating the angiotensin pathway beyond the cardiovascular and renal systems.

General mechanisms of fibrosis

The mammalian response to injury occurs in three distinct phases [8]. The initial inflammatory phase occurs immediately following insult and involves activation of the coagulation cascade, fibrin deposition, and infiltration of macrophages and neutrophils [9]. Following this, the proliferative phase is defined by angiogenesis, fibroblast proliferation, and differentiation [10,11]. Finally, in the remodeling phase, fibroblasts and myofibroblasts deposit a collagen-rich extracellular matrix that will ultimately become a scar that replaces the injured functional tissue. This process of healing is highly conserved across tissue types.

Fibrosis also occurs ubiquitously throughout the body as a pathologic response to chronic tissue injury and is essentially a persistence of the normal wound healing response. It is characterized by chronic inflammation and persistence of myofibroblasts ultimately resulting in excess accumulation of extracellular matrix and destruction of the normal tissue architecture. Fibrogenesis is most likely triggered by inflammation, whether or not inflammation leads to tissue repair or to fibrosis depending on the balance between extracellular matrix (ECM) synthesis and degradation [12]. In response to chronic tissue damage, ECM-producing cells, namely fibroblasts, undergo a process of activation characterized by proliferation and differentiation into myofibroblasts, which are the main cellular effectors of fibrosis [13]. These cells deposit large amounts of ECM proteins and express the contractile protein α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), which contributes to the decreased tissue compliance associated with fibrosis. This activation is regulated by several soluble factors including cytokines, growth factors, and products of oxidative stress [14,15]. Although several molecules are involved in this process, transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1) plays a pivotal role in triggering and sustaining fibrogenesis [16].

Renin-angiotensin system

In the classical description, decreased renal perfusion results in renin release from the juxtaglomerular cells of the kidney. This enzyme then cleaves angiotensinogen, produced in the liver, to angiotensin I which is subsequently converted to angiotensin II by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) in the lung. AngII acts systemically to regulate blood pressure as well as water and electrolyte homeostasis [17].

We now know that AngII is expressed and acts on almost all tissues. AngII signals through two main receptors, angiotensin receptor 1 (AT1) and angiotensin receptor 2 (AT2) [7]. AT1 mediates the ‘classical’ effects of AngII, namely regulation of blood pressure as well as sodium and water homeostasis. Locally, AT1 activation stimulates profibrotic downstream effects, namely inflammatory cell recruitment, angiogenesis, cellular proliferation, and accumulation of ECM [6,7].

Until recently, the role of AT2 was less well defined; however, recent research has revealed that AT2 receptor stimulation counteracts the harmful effects of AT1 signaling in fibrotic disease [18-20]. The so-called ‘protective arm’ of RAS has expanded to include the heptapeptide angiotensin 1 to 7 (Ang1-7), its receptor, Mas, and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which produces Ang1-7 from both AngI and AngII [21,22]. Activation of these counterregulatory systems has been shown to decrease inflammation, cell proliferation, and collagen deposition [21,23] and improve healing in experimental models of the cardiovascular, renal, immunologic, and neurologic systems [24]. Although studies have shown that both AT1 and AT2 receptors are upregulated after injury [23], the interplay between the two remains to be elucidated, particularly with regard to AT2. At present, mechanisms responsible for the regenerative effects associated with AT2 remain unclear. There is evidence that the anti-inflammatory effects of AT2 are in part related to inhibition of NF-κΒ-mediated transcription of inflammatory mediators; however, the downstream signaling effects remain a focus of ongoing research [19].

Angiotensin-TGF-β signaling

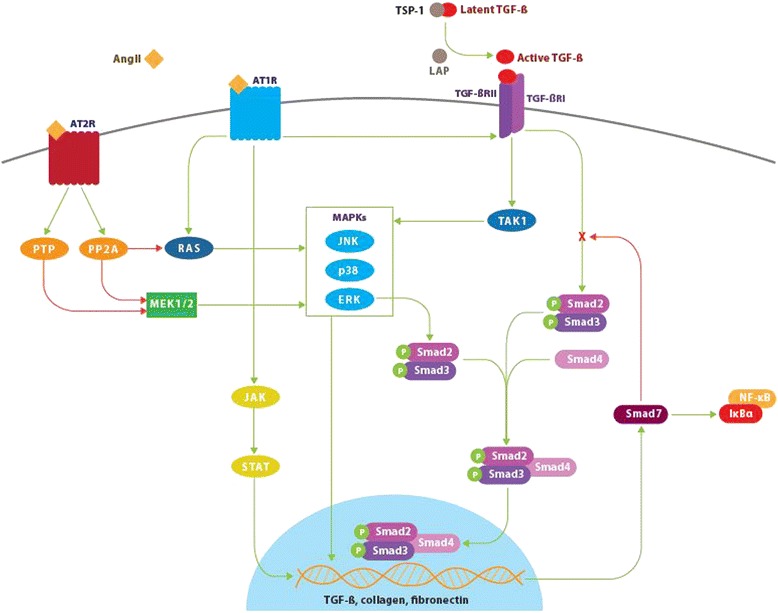

Despite the reported anti-inflammatory effects of the AT2 and Mas counter-regulatory systems, current research has continued to focus on the predominantly profibrotic role of AngII. The fibrogenic effects of AngII have been linked to its activation of TGF-β1 signaling (Figure 1) [25-27]. The TGF-β family has been extensively studied and is known to be involved in a variety of cellular functions, both physiologic and pathologic [28]. They are known to critically regulate tissue homeostasis and repair, immune and inflammatory responses, ECM deposition, cell differentiation and growth [29,30]. In mammals, three isoforms exist, designated TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and TGF-β3, with TGF-β1 being the most prevalent and expressed in almost all tissues [30]. Overexpression of TGF-β1 has been established as a key contributor to fibrosis in almost all tissues [16,25]. It potently stimulates myofibroblast differentiation and synthesis of ECM proteins [31]. TGF-β1 also acts to preserve ECM proteins by inhibiting the activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and inducing synthesis of tissue inhibitor metalloproteinases (TIMPs) [32]. Additionally, it strongly induces connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), a critical profibrotic mediator implicated in fibroblast proliferation, cellular adhesion, and ECM synthesis [33].

Figure 1.

Angiotensin II, transforming growth factor-β, and Smad signaling pathways. Binding of angiotensin II (AngII) to the angiotensin type 1 receptor (AT1) results in Smad2 and Smad3 phosphorylation via the ERK/p38/MAPK pathway. Activated Smad2 and Smad3 complex with Smad4 and translocate into the nucleus resulting in transcription of target genes including transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), procollagen I, procollagen III, and fibronectin. AngII-AT1 binding also directly activates TGF-β, which in turn activates Smad signaling in a similar manner. The P-Smad2/3-Smad4 complex induces transcription of Smad7, which has an inhibitory effect on TGF-β by targeting TGF-β receptor I (TGF-βR1) and Smads for ubiquitin-dependent degradation. Smad7 also inhibits NF-κB-driven inflammation via induction of the NF-κB inhibitor, IκBα. Conversely, activation of the AngII type 2 receptor (AT2) signaling has an inhibitory effect on both Smad and MAPK signaling pathways via dephosphorylating actions of phosphotyrosine phosphatase and protein phosphatase 2A. This produces antiproliferative and survival-promoting effects that oppose AT1-mediated fibrotic changes. Green lines indicate positive regulation. Red lines indicate negative regulation. Latent TGF-β binding protein (LTBP), TGF-β receptor 2 (TGF-βIIR), thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1), extracellular signal-relate kinase (ERK), nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), inhibitor of kappa B alpha (IκBα), protein serine/threonine phosphatase 2A (PP2A), phosphotyrosine phosphatase (PTP).

TGF-β1 is secreted as a latent precursor, bound to TGF-β1 latency-associated peptide (LAP), and requires proteolytic cleavage to become active [34]. Significant amounts of latent TGF-β1 are stored in the ECM of most tissues; however, activation of just a small fraction of latent TGF-β1 elicits maximal cellular response [35]. Following activation, TGF-β1 binds to the TGF-β1 type II receptor (TβRII), which subsequently complexes with and transphosphorylates the TGF-β1 type I receptor (TβRI), also known as ALK5 [36]. Active TβRI in turn activates the intracellular Smad signaling cascade by phosphorylating Smad2 and Smad3. Smad2 and Smad3 complex with Smad4 and translocate to the nucleus where they activate genes which code for extracellular matrix proteins including type I collagen and fibronectin. Activation of Smad3 also induces expression of Smad7, which inhibits TGF-β1-mediated effects, forming a negative feedback loop [30].

In addition to activation of Smad signaling, TGF-β1 can also activate several noncanonical mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways, namely extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK), p38 MAPK, and c-Jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK) [37,38]. These signaling cascades are activated in response to extracellular mitogenic and stress stimuli and act to further regulate Smad signaling as well as differentiation, proliferation, cell survival, and apoptosis. Activation of ERK has been shown to increase [39] or decrease [40] Smad signaling depending on the cell type. Conversely, activation of p38 MAPK and JNK typically potentiates TGF-β/Smad effects [41,42]. TGF-β also induces G0/G1 cell cycle arrest independent of Smad proteins via p38 MAPK [43] and has been shown to activate PI3 kinase/Akt, c-Abl, and Rho GTPase signaling cascades [37].

Although the cell signaling underlying AT2 activation is less well defined, there is evidence that AT2 activation results in attenuation of both canonical (Smad-dependent) and noncanonical (MAPK) TGF-β1 signaling cascades, particularly ERK signaling [44].

Angiotensin II and AT1 expression in fibrosis outside the heart and kidney

Both AT1 and AT2 have been shown to be upregulated after injury in the heart [45], blood vessels [46], brain [47], nerves [48], and skin [5]. This occurs as early as 24 h after injury and persists for up to 3 months [23].

Enhanced signaling of AngII via AT1 in injured tissue has been established in cardiovascular and renal disease as well as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and stroke [20,45,49]. Additionally, AngII blockade by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or AngII receptor blockers (ARBs) has been shown to significantly improve or reverse fibrosis in the skeletal muscle, heart, kidney, liver, and lung [50-55].

Angiotensin II-mediated AT1 activation has been shown to play an important role in the development of pulmonary fibrosis. Abdul-Hafez et al. demonstrated that the transition of normal lung fibroblasts to myofibroblasts by TGF-β1 in vitro is accompanied by robust expression of angiotensin mRNA, protein, and AngII peptide [56]. In addition, the increased contractility of lung fibroblasts isolated from fibrotic lungs has been shown to be dependent on angiotensin signaling [57].

Paizis et al. demonstrated that following liver injury, there is a marked increase in AT1 localized to areas of active fibrogenesis [58]. Expression of AT1 has been documented on activated, but not quiescent, hepatic stellate cells which are the key mediator of hepatic fibrosis, suggesting an important role of RAS in chronic liver disease [4]. Suekane et al. conducted a phenotypic analysis of colonic strictures isolated from Crohn’s patients and found that the fibromuscular cells accumulated within strictures strongly expressed AT1 [59].

In 2005, Steckelings et al. characterized the distribution of angiotensin receptor within normal and wounded human skin [23]. In normal, unwounded skin, AT1 and AT2 receptors are expressed on keratinocytes throughout the epidermis but not on dermal fibroblasts, despite the fact that both cell types have comparable levels of mRNA for both receptor subtypes. After wounding, AT1 and AT2 are upregulated in both epidermis and dermis within 48 h and persist within the scar for up to 3 months.

Hypertrophic scars, keloids, and scleroderma are pathologic fibrotic cutaneous conditions. Although histologically distinct, they all demonstrate increased expression of TGF-β1 and AngII activity [60-62]. Patients with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis (SSc) have significantly elevated serum levels of AngII and cutaneous angiotensinogen expression, which is not expressed in healthy skin [62]. In fact, subcutaneous infusion of AngII has been shown to induce dermal fibrosis in mice, opening up potential for a novel animal model of skin fibrosis [63].

Antifibrotic effects of AT1 inhibition

As previously stated, AngII exerts profibrotic effects via AT1 receptor signaling. Over nearly three decades, research has established the therapeutic efficacy of RAS blockade for management of hypertension, heart failure, and renal disease. The body of research focusing on targeting AngII in cardiac and renal fibrosis is extensive, and several thorough reviews have been written on this topic [64-66].

Experimental and clinical studies have provided evidence that targeting angiotensin may be of therapeutic benefit in the management of pulmonary fibrosis. In animal models, inhibition of AT1 signaling has been shown to attenuate experimental pulmonary fibrosis induced by bleomycin [67], radiation [68], and hyperoxia [69]. In a pilot clinical study, Couluris et al. evaluated the effect losartan, an AT1 antagonist, on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis progression over 12 months [34]. Preliminary data demonstrated stable or improved pulmonary function testing in 12 of the 17 patients treated with losartan. The authors concluded that losartan is a promising low-toxicity agent for treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis that requires more extensive evaluation in a placebo-controlled multicenter trial.

The literature also supports a beneficial effect of ACEI/ARBs in preventing or attenuating peritoneal fibrosis that occurs in long-term peritoneal dialysis patients [70]. Recently, losartan was shown to improve fibrosis in a rat model of Crohn’s disease [71]. Despite the large number of animal studies, there is a relative paucity of clinical data. There have been a number of small prospective human studies that have demonstrated a benefit of ACEI/ARB therapy in the treatment of liver fibrosis associated with hepatitis C [69-73]. While a number of clinical studies have demonstrated decreased liver fibrosis with losartan therapy [74,75], the multicenter HALT-C trial showed no significant reduction in the liver fibrosis score in patients on ACEI/ARB therapy [76]. This finding runs counter to the majority of available literature. As suggested by the authors of a recent review on the subject [77], the finding of the HALT-C analysis may be attributable to an increased proportion of diabetics in the ACEI/ARB treatment, a population known to experience more rapid progression of hepatitis C infection.

The potential role of ARB and ACEI in managing cutaneous fibrosis has not been extensively investigated. Marut et al. reported decreased Smad2/3, collagen concentration, and α-SMA expression in a mouse model of systemic sclerosis among animals treated with the ARB irbesartan [78]. In the clinical literature, a handful of case reports describe a subjective incidental improvement in the appearance of keloids or hypertrophic scars following initiation of ACEI or ARB therapy for hypertension [79,80]. Uzun et al. recently compared the effect the oral ACEI enalapril with intralesional triamcinolone in a rabbit ear hypertrophic scar model [81]. They found a modest reduction in scar elevation index in the enalapril group, with a greater reduction in the steroid group.

A number of animal studies have examined the effect of AngII blockade on skeletal muscle fibrosis. Losartan has been shown to reduce fibrosis and restore skeletal muscle strength in animal models of congenital muscular dystrophy and Marfan syndrome, primarily via inhibition of TGF-β1 signaling [55,82]. AT1 blockade was also shown to improve muscle regeneration after injury in a mouse gastrocnemius laceration model [83]. Although encouraging, many of these studies employed dosages that were well in excess of the human equivalent dose prescribed for hypertension management [55,83]. To this end, the clinical practicality of AT1 blockade for treatment of muscle injury remains unclear.

Antifibrotic effects of AT2 and ACE2/Ang-(1-7)/Mas axis stimulation

Currently, much of the research attention regarding angiotensin has been devoted to exploring function of AT2 and the Mas receptor, which, along with ACE2 and angiotensin 1 to 7, comprise the protective arm of the RAS. The recent availability of specific AT2 agonists has provided greater momentum in this area, with a number of drugs currently in preclinical or clinical development [18,24].

Stimulation of the ACE2/Ang-(1-7)/Mas axis has been shown to protect against bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, aspiration-induced lung injury, and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) [84-86]. Wagenaar et al. demonstrated that agonists of Mas and AT2 protect against cardiopulmonary disease in rats with neonatal hyperoxia-induced lung injury [87]. Fibroblasts isolated from human fibrotic lung produce significantly more collagen in vitro when compared to normal fibroblasts. Uhal et al. demonstrated that this phenomenon is abolished by administration of an ARB [88].

Ang-(1-7) has also been shown to play a protective role in hepatic fibrosis [89]. Infusion of Ang-(1-7) has been shown to reduce fibrosis and proliferation by inhibiting activation of hepatic stellate cells, which are a major fibrogenic cell type in the liver [90].

In skeletal muscle, Ang-(1-7) was shown to decrease fibrosis and increase muscle strength in an animal model of muscular dystrophy [91]. Morales et al. recently demonstrated that this effect was related to attenuation of AngII-induced TGF-β1 expression by Ang-(1-7)/Mas activation [92].

AT2 signaling has garnered considerable attention for its potential role in improving peripheral nerve regeneration. Both AT1 and AT2 receptors are expressed on Schwann cells [93], with a dramatic upregulation of AT2 expression observed following injury [94]. Subsequent animal experiments demonstrated that AT2 stimulation accelerates axonal regeneration and myelination [94,95]. In addition, the axonal recovery resulted in gain of function in a sciatic nerve injury model in the rat [94]. Most recently, AT2 stimulation has been shown to have a beneficial effect in a mouse spinal cord injury model [96].

The beneficial effects of AT2 stimulation have also been demonstrated in models of stroke and Alzheimer’s [97], McCarthy et al. demonstrated that AT2 stimulation in a rat prior to stroke reduced the severity of neuronal injury in a dose-dependent manner [98].

Conclusions

The presence of an autologous renin-angiotensin system extends beyond the classically recognized renal and cardiovascular systems and has been demonstrated in almost all tissues of the body. It is now recognized that AngII acts both independently and in synergy with TGF-β to induce fibrosis via the AT1 in a multitude of conditions including tubulointerstitial nephritis, myocardial infarction, and systemic sclerosis. Interestingly, recent research has described a paradoxically regenerative effect of the angiotensin system via stimulation of AT2. Activation of AT2 has been shown to ameliorate fibrosis in animal models of cardiovascular, renal, and neurologic diseases. Manipulation of AngII signaling via AT1 blockade and AT2 stimulation represent promising therapeutic approaches for inhibiting tissue fibrosis.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by an IWK Health Center Establishment Grant (MB) and through the Nova Scotia Ministry of Health (AM).

Abbreviations

- AngII

Angiotensin II

- RAS

Renin-angiotensin system

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- α-SMA

Alpha-smooth muscle actin

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor-beta

- ACE

Angiotensin-converting enzyme

- AT1

Angiotensin II type 1 receptor

- AT2

Angiotensin II type 2 receptor

- Ang1-7

Angiotensin (1-7)

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- MMP

Matrix metalloproteinase

- TIMPs

Tissue inhibitor metalloproteinase

- CTGF

Connective tissue growth factor

- LAP

Latency-associated peptide

- TβRII

TGF-β1 type II receptor

- TβRI

TGF-β1 type I receptor

- ERK

Extracellular signal-related kinase

- JNK

c-Jun-N-terminal kinase

- ARBs

AngII receptor blockers

- ACEi

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AM designed the concept, carried out the literature search, and drafted the manuscript. AW designed the figure, participated in the literature search, and helped draft the manuscript. MB performed an independent literature search and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Amanda M Murphy, Email: amurphy.dal@gmail.com.

Alison L Wong, Email: alison.martin@dal.ca.

Michael Bezuhly, Email: mbezuhly@dal.ca.

References

- 1.Lindpaintner K, Jin M, Wilhelm MJ, Suzuki F, Linz W, Schoelkens BA, et al. Intracardiac generation of angiotensin and its physiologic role. Circulation. 1988;77:I18–I23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bader M, Peters J, Baltatu O, Müller DN, Luft FC, Ganten D. Tissue renin-angiotensin systems: new insights from experimental animal models in hypertension research. J Mol Med (Berl) 2001;79:76–102. doi: 10.1007/s001090100210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engeli S, Negrel R, Sharma AM. Physiology and pathophysiology of the adipose tissue renin-angiotensin system. Hypertension. 2000;35:1270–1277. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.35.6.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bataller R, Sancho-Bru P, Ginès P, Lora JM, Al-Garawi A, Solé M, et al. Activated human hepatic stellate cells express the renin-angiotensin system and synthesize angiotensin II. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:117–25. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(03)00695-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steckelings UM, Wollschläger T, Peters J, Henz BM, Hermes B, Artuc M. Human skin: source of and target organ for angiotensin II. Exp Dermatol. 2004;13:148–54. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2004.0139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaschina E, Unger T. Angiotensin AT1/AT2 receptors: regulation, signalling and function. Blood Press. 2003;12:70–88. doi: 10.1080/08037050310001057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Gasparo M, Catt KJ, Inagami T, Wright JW, Unger T. International union of pharmacology. XXIII. The angiotensin II receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:415–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singer AJ, Clark RA. Cutaneous wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:738–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark RA, Lanigan JM, DellaPelle P, Manseau E, Dvorak HF, Colvin RB. Fibronectin and fibrin provide a provisional matrix for epidermal cell migration during wound reepithelialization. J Invest Dermatol. 1982;79:264–269. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12500075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Witte M, Barbul A. General principles of wound healing. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:509–528. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6109(05)70566-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nissen NN, Polverini PJ, Koch AE, Volin MV, Gamelli RL, DiPietro LA. Vascular endothelial growth factor mediates angiogenic activity during the proliferative phase of wound healing. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1445–1452. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pucilowska JB, Williams KL, Lund PK. Fibrogenesis. IV. Fibrosis and inflammatory bowel disease: cellular mediators and animal models. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G653–G659. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.279.4.G653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, Galli A, Bochaton-Piallat M-L, Gabbiani G. The myofibroblast: one function, multiple origins. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1807–1816. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rieder F, Fiocchi C. Intestinal fibrosis in inflammatory bowel disease: progress in basic and clinical science. CurrOpinGastroenterol. 2008;24:462–468. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3282ff8b36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powell DW, Mifflin RC, Valentich JD, Crowe SE, Saada JI, West AB. Myofibroblasts. I. Paracrine cells important in health and disease. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:C1–C9. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.001af.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biernacka A, Dobaczewski M, Frangogiannis NG. TGF-β signaling in fibrosis. Growth Factors. 2011;29:196–202. doi: 10.3109/08977194.2011.595714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall JE. Historical perspective of the renin-angiotensin system. Mol Biotechnol. 2003;24:27–39. doi: 10.1385/MB:24:1:27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bader M, Santos RA, Unger T, Steckelings UM. New therapeutic pathways in the RAS. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2012;13:505–8. doi: 10.1177/1470320312466519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rompe F, Artuc M, Hallberg A, Alterman M, Stroder K, Thone-Reineke C, et al. Direct angiotensin II type 2 receptor stimulation acts anti-inflammatory through epoxyeicosatrienoic acid and inhibition of nuclear factor kappaB. Hypertension. 2010;55:924–931. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.147843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meffert S, Stoll M, Steckelings UM, Bottari SP, Unger T. The angiotensin II AT2 receptor inhibits proliferation and promotes differentiation in PC12W cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1996;122:59–67. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(96)03873-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sumners C, Horiuchi M, Widdop RE, McCarthy C, Unger T, Steckelings UM. Protective arms of the renin-angiotensin-system in neurological disease. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2013;40:580–8. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santos RAS, Ferreira AJ, Verano-Braga T, Bader M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, angiotensin-(1-7) and Mas: new players of the renin-angiotensin system. J Endocrinol. 2013;216:R1–R17. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steckelings UM, Henz BM, Wiehstutz S, Unger T, Artuc M. Differential expression of angiotensin receptors in human cutaneous wound healing. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:887–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steckelings UM, Paulis L, Namsolleck P, Unger T. AT2 receptor agonists: hypertension and beyond. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2012;21:142–6. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328350261b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dobaczewski M, Chen W, Frangogiannis NG. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling in cardiac remodeling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:600–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schultz JEJ, Witt SA, Glascock BJ, Nieman ML, Reiser PJ, Nix SL, et al. TGF-beta1 mediates the hypertrophic cardiomyocyte growth induced by angiotensin II. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:787–796. doi: 10.1172/JCI0214190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun Y, Zhang J, Zhang JQ, Ramires FJA. Local angiotensin II and transforming growth factor-beta1 in renal fibrosis of rats. Hypertension. 2000;35:1078–1084. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.35.5.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gabriel VA. Transforming growth factor-beta and angiotensin in fibrosis and burn injuries. J Burn Care Res. 2009;30:471–81. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181a28ddb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang L, Pang Y, Moses HL. TGF-beta and immune cells: an important regulatory axis in the tumor microenvironment and progression. Trends Immunol. 2010;31:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schiller M, Javelaud D, Mauviel A. TGF-beta-induced SMAD signaling and gene regulation: consequences for extracellular matrix remodeling and wound healing. J Dermatol Sci. 2004;35:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Desmoulière A, Geinoz A, Gabbiani F, Gabbiani G. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 induces alpha-smooth muscle actin expression in granulation tissue myofibroblasts and in quiescent and growing cultured fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:103–111. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mauviel A. Transforming growth factor-beta: a key mediator of fibrosis. Methods Mol Med. 2005;117:69–80. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-940-0:069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rupérez M, Lorenzo O, Blanco-Colio LM, Esteban V, Egido J, Ruiz-Ortega M. Connective tissue growth factor is a mediator of angiotensin II-induced fibrosis. Circulation. 2003;108:1499–505. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000089129.51288.BA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koli K, Saharinen J, Hyytiäinen M, Penttinen C, Keski-Oja J. Latency, activation, and binding proteins of TGF-β. Microsc Res Tech. 2001;52:354–362. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20010215)52:4<354::AID-JEMT1020>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Annes JP, Munger JS, Rifkin DB. Making sense of latent TGFbeta activation. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:217–224. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Massagué J. How cells read TGF-beta signals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:169–178. doi: 10.1038/35043051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature. 2003;425:577–584. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang YE. Non-Smad pathways in TGF-beta signaling. Cell Res. 2009;19:128–139. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Funaba M, Zimmerman CM, Mathews LS. Modulation of Smad2-mediated signaling by extracellular signal-regulated kinase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41361–41368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kretzschmar M, Doody J, Timokhina I, Massague J. A mechanism of repression of TGF b / Smad signaling by oncogenic Ras. Genes Dev. 1999;13:804–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Furukawa F, Matsuzaki K, Mori S, Tahashi Y, Yoshida K, Sugano Y, et al. p38 MAPK mediates fibrogenic signal through Smad3 phosphorylation in rat myofibroblasts. Hepatology. 2003;38:879–89. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshida K, Matsuzaki K, Mori S, Tahashi Y, Yamagata H, Furukawa F, et al. Transforming growth factor-β and platelet-derived growth factor signal via c-Jun N-terminal kinase-dependent Smad2/3 phosphorylation in rat hepatic stellate cells after acute liver injury. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1029–1039. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62324-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seay U, Sedding D, Krick S, Hecker M, Seeger W, Eickelberg O. Transforming growth factor - NL-dependent growth inhibition in primary vascular smooth muscle cells is p38-dependent. 2005, 315:1005–1012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Habashi J, Doyle J, Holm T, Aziz H, Schoenhoff F, Bedja D, et al. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor signaling attenuates aortic aneurysm in mice through ERK antagonism. Science. 2011;332:361–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Busche S, Gallinat S, Bohle RM, Reinecke A, Seebeck J, Franke F, et al. Expression of angiotensin AT(1) and AT(2) receptors in adult rat cardiomyocytes after myocardial infarction. A single-cell reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction study. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:605–611. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64571-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Viswanathan M, Strömberg C, Seltzer A, Saavedra JM. Balloon angioplasty enhances the expression of angiotensin II AT1 receptors in neointima of rat aorta. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:1707–1712. doi: 10.1172/JCI116043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Makino I, Shibata K, Ohgami Y, Fujiwara M, Furukawa T. Transient upregulation of the AT2 receptor mRNA level after global ischemia in the rat brain. Neuropeptides. 1996;30:596–601. doi: 10.1016/S0143-4179(96)90043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gallinat S, Yu M, Dorst A, Unger T, Herdegen T. Sciatic nerve transection evokes lasting up-regulation of angiotensin AT2 and AT1 receptor mRNA in adult rat dorsal root ganglia and sciatic nerves. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;57:111–122. doi: 10.1016/S0169-328X(98)00079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wright JW, Kawas LH, Harding JW. A role for the brain RAS in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson's diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2013;4:158. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2013.00158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tzanidis A, Lim S, Hannan RD, See F, Ugoni AM, Krum H. Combined angiotensin and endothelin receptor blockade attenuates adverse cardiac remodeling post-myocardial infarction in the rat: possible role of transforming growth factor beta(1) J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:969–981. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lim DS, Lutucuta S, Bachireddy P, Youker K, Evans A, Entman M, et al. Angiotensin II blockade reverses myocardial fibrosis in a transgenic mouse model of human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2001;103:789–791. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.6.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Agarwal R, Siva S, Dunn SR, Sharma K. Add-on angiotensin II receptor blockade lowers urinary transforming growth factor-beta levels. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:486–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Boffa J-J, Lu Y, Placier S, Stefanski A, Dussaule J-C, Chatziantoniou C. Regression of renal vascular and glomerular fibrosis: role of angiotensin II receptor antagonism and matrix metalloproteinases. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1132–1144. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000060574.38107.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Couluris M, Kinder BW, Xu P, Gross-King M, Krischer J, Panos RJ. Treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with losartan: a pilot project. Lung. 2012;190:523–7. doi: 10.1007/s00408-012-9410-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elbaz M, Yanay N, Aga-Mizrachi S, Brunschwig Z, Kassis I, Ettinger K, et al. Losartan, a therapeutic candidate in congenital muscular dystrophy: studies in the dy(2 J) /dy(2 J) mouse. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:699–708. doi: 10.1002/ana.22694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abdul-Hafez A, Shu R, Uhal BD. JunD and HIF-1α mediate transcriptional activation of angiotensinogen by TGF-β1 in human lung fibroblasts. FASEB J. 2009;23:1655–1662. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-114611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Uhal BD, Li X, Piasecki CC, Molina-Molina M. Angiotensin signalling in pulmonary fibrosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44:465–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paizis G, Cooper ME, Schembri JM, Tikellis C, Burrell LM, Angus PW. Up-regulation of components of the renin-angiotensin system in the bile duct-ligated rat liver. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1667–1676. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suekane T, Ikura Y, Watanabe K, Arimoto J, Iwasa Y, Sugama Y, et al. Phenotypic change and accumulation of smooth muscle cells in strictures in Crohn’s disease: relevance to local angiotensin II system. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:821–30. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0232-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang K, Garner W, Cohen L, Rodriguez J, Phan S. Increased types I and III collagen and transforming growth factor-beta 1 mRNA and protein in hypertrophic burn scar. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:750–754. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12606979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tang H-T, Cheng D-S, Jia Y-T, Ben D-F, Ma B, Lv K-Y, et al. Angiotensin II induces type I collagen gene expression in human dermal fibroblasts through an AP-1/TGF-beta1-dependent pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;385:418–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kawaguchi Y, Takagi K, Hara M, Fukasawa C, Sugiura T, Nishimagi E, et al. Angiotensin II in the lesional skin of systemic sclerosis patients contributes to tissue fibrosis via angiotensin II type 1 receptors. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:216–26. doi: 10.1002/art.11364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stawski L, Han R, Bujor AM, Trojanowska M. Angiotensin II induces skin fibrosis: a novel mouse model of dermal fibrosis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R194. doi: 10.1186/ar4028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Varagic J, Ahmad S, Nagata S, Ferrario CM. ACE2: angiotensin II/angiotensin-(1-7) balance in cardiac and renal injury. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2014;16:420. doi: 10.1007/s11906-014-0420-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wysocki J, González-Pacheco FR, Batlle D. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: Possible role in hypertension and kidney disease. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2008;10:70–77. doi: 10.1007/s11906-008-0014-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Batlle D, Soler MJ, Wysocki J. New aspects of the renin-angiotensin system: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 - a potential target for treatment of hypertension and diabetic nephropathy. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2008;17:250–7. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3282f945c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Meng Y, Li X, Cai S-X, Tong W-C, Cheng Y-X. Perindopril and losartan attenuate bleomycin A5-induced pulmonary fibrosis in rats. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2008;28:919–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Molteni A, Moulder JE, Cohen EF, Ward WF, Fish BL, Taylor JM, et al. Control of radiation-induced pneumopathy and lung fibrosis by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and an angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker. Int J Radiat Biol. 2000;76:523–532. doi: 10.1080/095530000138538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li J-J, Xue X-D. Protection of captopril against chronic lung disease induced by hyperoxia in neonatal rats. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2007;9:169–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kolesnyk I, Noordzij M, Dekker FW, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT. A positive effect of AII inhibitors on peritoneal membrane function in long-term PD patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:272–7. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wengrower D, Zanninelli G, Latella G, Necozione S, Metanes I, Israeli E, et al. Losartan reduces trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid-induced colorectal fibrosis in rats. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26:33–9. doi: 10.1155/2012/628268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yoshiji H, Kuriyama S, Noguchi R, Yoshii J, Ikenaka Y, Yanase K, et al. Combination of interferon-beta and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, perindopril, attenuates the murine liver fibrosis development. Liver Int. 2005;25:153–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yoshiji H, Noguchi R, Kojima H, Ikenaka Y, Kitade M, Kaji K, et al. Interferon augments the anti-fibrotic activity of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor in patients with refractory chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6786–6791. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i42.6786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Colmenero J, Bataller R, Sancho-Bru P, Domínguez M, Moreno M, Forns X, et al. Effects of losartan on hepatic expression of nonphagocytic NADPH oxidase and fibrogenic genes in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297:G726-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Sookoian S, Fernandez MA, Castano G. Effects of six months losartan administration on liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C patients: a pilot study. World J Gastroenterol WJG. 2005;11:7560–7563. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i48.7560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Abu Dayyeh BK, Yang M, Dienstag JL, Chung RT. The effects of angiotensin blocking agents on the progression of liver fibrosis in the HALT-C Trial cohort. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:564–568. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1507-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Grace JA, Herath CB, Mak KY, Burrell LM, Angus PW. Update on new aspects of the renin-angiotensin system in liver disease: clinical implications and new therapeutic options. Clin Sci (Lond) 2012;123:225–39. doi: 10.1042/CS20120030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Marut W, Kavian N, Servettaz A, Hua-Huy T, Nicco C, Chéreau C, et al. Amelioration of systemic fibrosis in mice by angiotensin II receptor blockade. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1367–77. doi: 10.1002/art.37873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Iannello S, Milazzo P, Bordonaro F, Belfiore F. Low-dose enalapril in the treatment of surgical cutaneous hypertrophic scar and keloid - two case reports and literature review. MedGenMed. 2006;8:60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ardekani GS, Aghaei S, Nemati MH, Handjani F, Kasraee B. Treatment of a postburn keloid scar with topical captopril: report of the first case. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:112e–113e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31819a34db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Uzun H, Bitik O, Hekimoğlu R, Atilla P, Kaykçoğlu AU. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor enalapril reduces formation of hypertrophic scars in a rabbit ear wounding model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:361e–71e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31829acf0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cohn RD, van Erp C, Habashi JP, Soleimani AA, Klein EC, Lisi MT, et al. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade attenuates TGF-beta-induced failure of muscle regeneration in multiple myopathic states. Nat Med. 2007;13:204–10. doi: 10.1038/nm1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bedair HS, Karthikeyan T, Quintero A, Li Y, Huard J. Angiotensin II receptor blockade administered after injury improves muscle regeneration and decreases fibrosis in normal skeletal muscle. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:1548–54. doi: 10.1177/0363546508315470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Imai Y, Kuba K, Rao S, Huan Y, Guo F, Guan B, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature. 2005;436:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature03712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kuba K, Imai Y, Rao S, Gao H, Guo F, Guan B, et al. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat Med. 2005;11:875–879. doi: 10.1038/nm1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shenoy V, Ferreira AJ, Qi Y, Fraga-Silva RA, Díez-Freire C, Dooies A, et al. The angiotensin-converting enzyme 2/angiogenesis-(1-7)/Mas axis confers cardiopulmonary protection against lung fibrosis and pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1065–72. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1840OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wagenaar GTM, Laghmani EH, Fidder M, Sengers RMA, de Visser YP, de Vries L, et al. Agonists of MAS oncogene and angiotensin II type 2 receptors attenuate cardiopulmonary disease in rats with neonatal hyperoxia-induced lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;305:L341–51. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00360.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Uhal BD, Kim JK, Li X, Molina-Molina M. Angiotensin-TGF-beta 1 crosstalk in human idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: autocrine mechanisms in myofibroblasts and macrophages. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:1247–1256. doi: 10.2174/138161207780618885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.De Macêdo SM, Antunes Guimarães T, Feltenberger JD, Santos SHS. The role of renin-angiotensin system modulation on treatment and prevention of liver diseases. Peptides. 2014;62C:189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pereira RM, Dos Santos RAS, Teixeira MM, Leite VHR, Costa LP, da Costa Dias FL, et al. The renin-angiotensin system in a rat model of hepatic fibrosis: evidence for a protective role of Angiotensin-(1-7) J Hepatol. 2007;46:674–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Acuña MJ, Pessina P, Olguin H, Cabrera D, Vio CP, Bader M, et al. Restoration of muscle strength in dystrophic muscle by angiotensin-1-7 through inhibition of TGF-β signalling. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:1237–49. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Morales MG, Abrigo J, Meneses C, Simon F, Cisternas F, Rivera JC, et al. The Ang-(1-7)/Mas-1 axis attenuates the expression and signalling of TGF-β1 induced by AngII in mouse skeletal muscle. Clin Sci (Lond) 2014;127:251–64. doi: 10.1042/CS20130585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bleuel A, de Gasparo M, Whitebread S, Püttner I, Monard D. Regulation of protease nexin-1 expression in cultured Schwann cells is mediated by angiotensin II receptors. J Neurosci. 1995;15:750–761. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00750.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Reinecke K, Lucius R, Reinecke A, Rickert U, Herdegen T, Unger T. Angiotensin II accelerates functional recovery in the rat sciatic nerve in vivo: role of the AT2 receptor and the transcription factor NF-kappaB. FASEB J. 2003;17:2094–6. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1193fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lucius BR, Gallinat S, Rosenstiel P, Herdegen T, Sievers J, Unger T. Axonal regeneration in the optic nerve of adult rats. J Exp Med. 1998;188:661–670. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.4.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Namsolleck P, Boato F, Schwengel K, Paulis L, Matho KS, Geurts N, et al. AT2-receptor stimulation enhances axonal plasticity after spinal cord injury by upregulating BDNF expression. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;51:177–91. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jing F, Mogi M, Sakata A, Iwanami J, Tsukuda K, Ohshima K, et al. Direct stimulation of angiotensin II type 2 receptor enhances spatial memory. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:248–55. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.McCarthy CA, Vinh A, Callaway JK, Widdop RE. Angiotensin AT2 receptor stimulation causes neuroprotection in a conscious rat model of stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:1482–1489. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.531509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]