Abstract

The Probability of Treatment Benefit (PTB) chart (Beidas et al., 2013; Lindhiem, Kolko, & Cheng, 2012) is a decision-support tool that quantifies, in absolute terms, the probability that an individual patient will benefit from a psychological treatment based on the individual's pre-treatment characteristics. The demand for such a tool has increased with the growing emphasis on personalized medicine and the need for selecting a treatment from an expanding list of evidence-based models. This method has the potential to provide clinicians and mental health consumers with a practical and interpretable means of comparing treatment options for individuals whose benefit from a particular treatment may differ substantially. We provide a practice update and demonstrate how to develop a PTB chart using data from a randomized controlled trial examining the efficacy of two approaches for treating posttraumatic stress disorder based on patients’ pre-treatment exposure to multiple types of interpersonal violence. Step-by-step instructions for applying the PTB method are provided.

Keywords: Treatment benefit, decision-support tool, patient-centered treatment

As the list of evidence-based and empirically supported mental health treatment models grows, practitioners and consumers alike face difficult decisions pertaining to treatment selection and little support to guide them. Although there is an emphasis on the personalization of medicine, the field of mental health is dependent on a non-optimal system for classifying disorders – one that allows for significant heterogeneity within classifications and impedes our ability to follow a clear path from diagnosis to treatment (Hyman, 2010). Further, a known limitation of current methods for determining the efficacy of treatment models is the artificial homogeneity of the patient sample that results from stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria and use of highly controlled settings (Chorpita, Bernstein, & Daleiden, 2008). Despite these drawbacks, information that may help to match treatment options to patients based on their individual differences, while limited, is becoming increasingly available through more inclusive treatment outcome and effectiveness studies that purposefully aim to examine potential moderators of treatment outcome and response (Kraemer, Frank, & Kupfer, 2011).

Even so, this information is not readily accessible, nor clinically practical, for many practitioners and consumers. Traditional approaches to describing the effectiveness of treatments are useful, but do not convey the probability that a treatment will benefit an individual patient. Effect sizes, such as Cohen’s d, indicate the magnitude of a treatment’s effect relative to a control condition (treatment-control ES) or the mean of the treatment condition at baseline (pre-post ES). Newer metrics such as the Absolute Risk Reduction (ARR) and Number Needed to Treat (NNT) provide clinical utility, but also describe average benefits relative to another treatment or a control condition. In order to achieve a personalized approach to treating mental health problems, a clinically practical method is needed to supplement these strategies towards informing practitioners and consumers about pre-treatment characteristics associated with treatment response and outcome and potentially relevant in treatment planning. Because moderating variables rarely predict an outcome with absolute certainty, such a method must also provide guidance in probabilistic terms. Herein lies the challenge in designing a method that is empirically useful, yet accessible to clinicians and clinical researchers.

The Probability of Treatment Benefit (PTB) method offers such a method (Beidas et al., 2013; Lindhiem, Kolko, & Cheng, 2012). The PTB approach quantifies, in absolute terms (i.e., not relative to another treatment or control condition), the probability that an individual patient (i.e., not patients in the aggregate) will show a particular response or achieve a particular outcome based on his or her pre-treatment characteristics. Whereas traditional metrics address the question “How big is the average benefit?” the PTB method addresses the question “What is the probability this treatment will benefit this individual based on his or her characteristics?” The PTB method can be applied to data from treatment outcome research to quantify the likelihood that a patient will experience a particular outcome given his or her baseline characteristics or other known moderators of change.

The PTB method is increasingly being promoted as a practical tool for clinicians interested in evidence-based assessment and treatment planning (e.g., Christon, McLeod, & Jensen-Doss, in press; Koster, Defreyne, Putter, & Vanden Bogaerde, 2013; Youngstrom, Choukas-Bradley, Calhoun, & Jensen-Doss, in press). Successful application of the PTB method will depend on collaboration between clinical researchers and practicing clinicians. Clinical researchers who are conducting psychotherapy efficacy or effectiveness research can use the PTB method to organize and communicate their empirical findings in a way that will be tangible to and applicable for clinicians. Clinicians can rely on data prepared using the PTB method to best communicate treatment options to patients. In this practice update we aim to serve both clinical researchers and practicing clinicians who might take advantage of the PTB method. For clinical researchers we provide step-by-step instructions on how to construct a PTB chart using their outcome data. For clinicians we provide a strong rationale for using the PTB method, as well as clinical vignettes to share examples of how the PTB method can be applied to practice. For both the researcher and the clinician, we illustrate the construction and application of a PTB chart based on effectiveness data from a study examining treatments for violence-related psychopathology. Application of the PTB method in the field of interpersonal violence and psychological trauma, specifically, may help researchers and clinicians alike to prepare and communicate information about differential effects of the growing list of trauma-specific interventions based on pre-treatment patient or trauma characteristics.

Constructing a PTB Chart

Step One: Identify and select a known pre-treatment moderator of treatment outcome

The PTB method begins with the choice of a pre-treatment variable that is known to be associated with treatment response or outcome, often based on a review of relevant research. This variable is used to stratify the dataset. This is straightforward for categorical variables. For continuous variables (e.g., perceived social support), established cut-off scores may be used, or consider categorizing the sample according to percentiles.

Step Two: Selecting meaningful measures of treatment response and outcome

Because treatment response reflects the magnitude of a patient’s improvement across treatment, psychometrically sound dimensional measures of symptom severity or functional impairment must be selected. In contrast, treatment outcome reflects post-treatment status (e.g., whether the patient’s score on the outcome measure exceeds a threshold level for clinically significant severity) regardless of pre-treatment status. Since the goal is to achieve individualized predictions of outcome in probabilistic terms, categorical or dichotomous measures (or a variable that can be converted from continuous to categorical) should be chosen. It is important that the outcome measure reflects the clinical significance of a patient’s impairment at post-treatment.

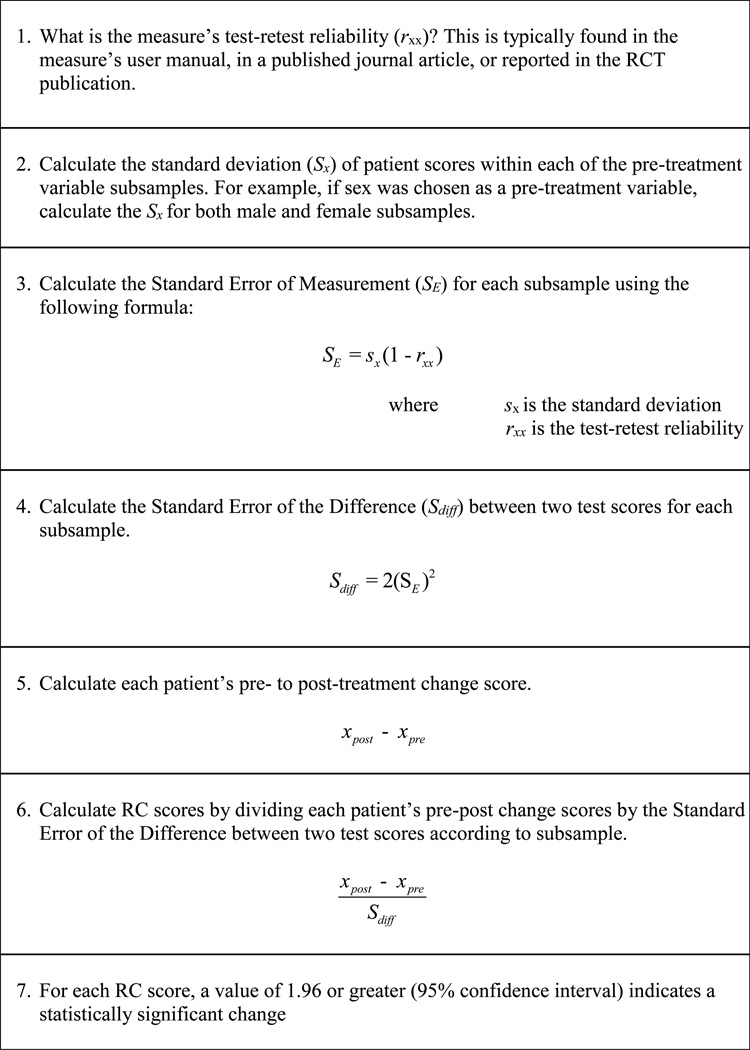

Treatment response measures, in contrast, communicate the degree of clinically significant change across treatment. Determining whether a patient demonstrates a reliable and clinically significant improvement in or worsening of symptoms (i.e., deterioration) from pre- to post-treatment can be achieved using the reliable change index (RCI; Jacobson & Truax, 1991), the most frequently used statistical formula for assessing the reliability of individual change scores. Figure 1 provides steps for calculating reliable change (RC) scores.

Figure 1.

How to Calculate Reliable Change Scores using the Reliable Change Index.

Step Three: Creating the PTB Chart

Calculating the probabilities that will make up the PTB Chart will depend on how many predictors are in the model and how many levels there are in each predictor. The simplest model is one in which there is just one predictor with two levels. In this case, probabilities can be derived from observing proportions in a crosstab analysis of the predictor and outcome variables.

These probabilities are identical to what would be produced if derived from log odds ratios generated from a logistic regression analysis. The latter is considered a saturated model because the expected counts and observed counts are identical. However, when a model has a predictor with more than two levels or has multiple predictors, one must conduct a logistic regression analysis, and then convert the log odds ratios to probabilities. Ordinal predictors with more than two levels can be entered into a logistic regression as is; however, for categorical pre-treatment variables with more than two levels, it will be necessary to create dichotomous dummy variables coded as 0 or 1. After running the model, the log odds of each outcome are calculated for each subsample and converted to probabilities. The log odds can be computed by summing the unstandardized beta weights multiplied by their respective codes (i.e., 0 or 1):

The log odds is then converted to a probability using the following equation:

The final columns of the PTB Chart present expected responses, both improvement and deterioration, which are simply the median change scores of the dimensional treatment response measure for each subsample, and expected outcome, which is the median post-treatment score.

An Illustration

For illustration we applied the PTB method to data from a randomized clinical trial (RCT) demonstrating the effectiveness of an affect regulation treatment for PTSD in comparison to a social problem-solving treatment or a waitlist control condition with a sample of mothers with extensive but variable histories of interpersonal violence (Ford, Steinberg, & Zhang, 2011). Consistent with prior evidence with violence-exposed families (Samuelson, Krueger, & Wilson, 2012), enhanced maternal emotion regulation was found to contribute to positive parenting outcomes as well as to the mothers’ recovery from PTSD. However, the question of whether women with more extensive histories of violence exposure—which has been shown to be associated with poorer life outcomes (Song, 2012)—benefited as much as those with less extensive interpersonal violence histories from the emotion regulation therapy was not addressed.

Therapies with the strongest research evidence-base for the treatment of PTSD (Cahill, Rothbaum, Resick, & Folette, 2009) are designed to help patients to process trauma memories in order to reduce avoidance and associated re-experiencing, emotional numbing, and hyperarousal. However, the rationale for testing an emotion regulation therapy that does not include a required trauma memory processing component is that patients with extensive interpersonal violence, associated with severe emotion dysregulation (i.e., high levels of anger, interpersonal problems, guilt, and shame), tend to respond less well to trauma memory processing therapies (Jaycox & Foa, 1996) and to be more likely to drop out from trauma memory processing therapy than therapy designed to directly address affect regulation and relational problems in treatment (McDonagh et al., 2005).

Although the Ford et al. (2011) RCT did not compare these therapies to trauma memory processing, results supported the effectiveness of both the affect-regulation and social problem solving therapies in reducing trauma-related symptoms relative to a waitlist control group (Ford et al., 2011). Applying these data to the PTB method illustrates these results in a form that is arguably more clinically useful to clinicians and consumers. Specifically, the PTB method presents these results in a probabilistic way that highlights the benefit of patients participating in one of these therapies as opposed to receiving nothing at all, and especially for patients with high levels of interpersonal violence. For illustration purposes, we chose severity of interpersonal violence as the pre-treatment variable. Patients were classified as having either high or low exposure to interpersonal violence following a median split (i.e., 4 types) of the number of types of interpersonal violence they reported. Although using a median split on continuous data is a suboptimal way of determining the threshold at which to form subgroups, the PTB method relies on categorical data. Despite this limitation, using a median split can still be an effective way to illustrate complex relationships between continuous variables and treatment response. Below we summarize the Ford et al. (2011) sample and methods prior to describing the steps towards creating the PTB chart. Please refer to the original article for a complete description of the study sample and methodology.

Participants

Participants were 146 women (ages 18–45; M = 30.7, SD = 6.9) recruited from health clinics, family service centers, community centers, and residential treatment centers in the Hartford Connecticut area and randomized to waitlist control (N = 45), affect regulation therapy (N = 48), or social problem solving therapy (N = 53). Ethnicity was 40% African American, 18% Latina, 41% White (Non-Hispanic), and 1% other. Most participants lived without a partner (63%) and had never married or were divorced, separated, or widowed. More than half (57%) had not completed high school or had a terminal high school degree. Almost half (48%) had been homeless. Most had family incomes below $30,000 per year (94%) with a median annual income of $5,361. All participants had full/partial PTSD and most had a comorbid Axis I disorder (72%). A total of 100 (67.8%) completed post-treatment or post-wait interviews. Of those assigned to the control condition, 20% did not respond or withdrew and 2.2% moved out of state. Of those assigned to PCT, 35.8% did not respond or withdrew, and of those assigned to TARGET, 33.3% did not respond or withdrew. See Ford et al. (2011) for a full sample description.

Measures

The Traumatic Events Screening Inventory (TESI; Ford & Smith, 2008) was used to assess violence experiences including accident/illness, separation/loss, family violence, community violence, physical assault, and sexual assault/molestation. Independent inter-rater reliability for the presence/absence of a traumatic event was strong, ranging from κ = .84 to .91. High and low interpersonal violence was defined by a median cut of 4 types of this trauma, including several types of family or community physical or sexual violence.

PTSD was assessed with the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; Blake et al., 1995; Weathers, Keane, & Davidson, 2001), a reliable and well-validated structured interview for DSM-IV diagnoses of full and partial PTSD that also yields symptom severity scores defined by the intensity (0 “none” to 4 “extreme distress”) and frequency (0 “none” to 4 “daily or almost daily”) of symptoms. Independent inter-rater reliability for the CAPS total score (intraclass correlation = .97 at baseline and .94 at posttest/follow-up) and detecting full/partial PTSD (92% agreement, K = .77) was strong in the current sample. Severity scores > 40 are in the clinical range, with > 70 reflecting severe PTSD (Weathers et al., 2001).

Therapy Interventions

Trauma Affect Regulation: Guide for Education and Therapy (TARGET; Ford & Russo, 2006) is a manualized 12-session therapy that teaches affect regulation skills designed to reduce PTSD and associated impairment without requiring trauma memory re-telling. Present Centered Therapy (PCT; McDonagh-Coyle et al., 2005), is a manualized 12-session skills-based therapy that focuses on problems in relationships due to the betrayal, stigma, powerlessness, and sexualization associated with exposure to interpersonal violence and also does not require trauma memory re-telling (McDonagh-Coyle et al., 2005).

PTB Analytic Procedure

Step One

The sample was stratified according to treatment condition (Waitlist Control vs. PCT vs. TARGET) and interpersonal violence (low vs. high), which resulted in six subsamples: Waitlist Control/High Violence (n = 21), Waitlist Control/Low Violence (n = 14), PCT/High Violence (n = 21), PCT/Low Violence (n = 13), TARGET/High Violence (n = 17), and TARGET/Low Violence (n = 14).

Step Two

The CAPS was chosen as a measure of treatment response and outcome. Three dichotomous outcomes were created: (a) falling below clinical threshold at post-treatment, (i.e., positive treatment outcome), (b) showing reliable improvement on the CAPS per the RCI (i.e., positive treatment response), and (c) showing reliable deterioration on the CAPS per the RCI (i.e., negative treatment response).

Step Three

A logistic regression analysis was conducted for each of the three outcome measures. Two dummy variables were created to reflect treatment condition: TARGET (0 = no, 1 = yes) and PCT (0 = no, 1 = yes). The dummy variables and the interpersonal violence variable made up the three predictors, each with two levels. Log odds were calculated by taking the sum of the unstandardized beta weights in the regression analysis, multiplied by their respective codes (i.e., 0 or 1):

Log odds were then converted to probabilities using the following equation.

Interpretation

The following predictive statements can be made based on the PTB Chart (see Table 1):

A PTSD patient who does not receive treatment is unlikely to fall below clinical threshold on the CAPS (< 30% probability) or to show reliable improvement on the CAPS (< 40% probability) during a 3-month time frame.

An untreated PTSD patient classified as having a high level of interpersonal violence, compared to a patient with a low level of interpersonal violence, is less likely to fall below clinical threshold on the CAPS (15.6% vs. 26.7% probabilities, respectively) or to show reliable improvement on the CAPS relative to baseline (24.4% vs. 34.9% probabilities, respectively) during a 3-month period.

A PTSD patient who receives PCT or TARGET has an approximately 50% probability of achieving a positive treatment outcome or response.

A PTSD patient classified as having a high level of interpersonal violence is less likely, compared to a patient with a low level of interpersonal violence, to have a positive treatment outcome after receiving PCT (43.5% vs. 60.4%, respectively) or TARGET (50.6% vs. 67.1%, respectively) or a positive response to receiving PCT (54.3% vs. 66.3%, respectively) or TARGET (55.9% vs. 67.8%, respectively).

Regardless of degree of violence or involvement in treatment, it is highly unlikely for a patient to show deterioration in PTSD symptoms. However, patients classified as having severe interpersonal violence are slightly more likely than other patients to experience deterioration in PTSD symptoms.

In comparison to a PTSD patient with low interpersonal violence, who is expected to show a reduction of 19 points on the CAPS with an estimated final score of 50 over the 3-month period, a patient with high interpersonal violence is expected to show a negligible reduction of points on the CAPS, with an estimated final score of 78.

Table 1.

Probability of Treatment Benefit for Treatment Completers Using Pre- to Post-Treatment CAPS

| Probability of Falling Below Clinical Threshold at Post-treatment |

Probability of Reliable Improvement per the RCI |

Probability of Reliable Deterioration per the RCI |

Expected Responsea |

Expected Deteriorationb |

Expected Outcomec |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | ||||||

| High Interpersonal Violence (n = 21) | 15.6% | 24.4% | 4.8% | 0 pts | 5 pts | 78 |

| Low Interpersonal Violence (n = 14) | 26.7% | 34.9% | 0.0% | 19 pts | 0 pts | 50 |

| PCT | ||||||

| High Interpersonal Violence (n = 21) | 43.5% | 54.3% | 4.8% | 23 pts | 0 | 36 |

| Low Interpersonal Violence (n = 13) | 60.4% | 66.3% | 0.0% | 21 pts | 0 | 34 |

| TARGET | ||||||

| High Interpersonal Violence (n = 17) | 50.6% | 55.9% | 0.0% | 19 pts | 0 | 36 |

| Low Interpersonal Violence (n = 14) | 67.1% | 67.8% | 0.0% | 33 pts | 0 | 34 |

Expected reduction in PTSD symptom level on the CAPS (i.e., median change score when positive)

Expected increase in PTSD symptom level on the CAPS (i.e., median change score when negative)

Expected CAPS score post-treatment (i.e., median post-treatment score)

How Does the PTB Output Compare to Other Effect Size Metrics?

For comparison, Table 2 presents effect size metrics including Cohen’s d, NNT, and ARR. Cohen’s d indicates that the mean post-treatment CAPS score of patients in each treatment condition is about one standard deviation lower than the mean of patients in the waitlist control condition. The NNT indicates that two patients receiving TARGET and three patients receiving PCT would have to be treated before one patient has a better post-treatment outcome on the CAPS relative to the control patients. For both treatments, three patients would need to be treated in order for one patient to evidence a better pre-post response to treatment (as defined using the RCI) compared to patients in the control condition. Finally, the absolute arithmetic difference in the rate of clinical outcome (i.e., falling below clinical threshold or showing reliable improvement) between treatment and control participants is .30 for PCT versus a somewhat higher level of .33–.38 for TARGET according to the ARR metrics.

Table 2.

Effect Size Metrics Using Pre- to Post-Treatment CAPS

| Cohen’s d | NNT Below Clinical Threshold |

NNT Reliably Better |

ARR Below Clinical Threshold |

ARR Reliably Better |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCT | 1.03 | 3 | 3 | .30 | .30 |

| TARGET | 1.01 | 2 | 3 | .38 | .33 |

Note. NNT = Number Needed to Treat, ARR = Absolute Risk Reduction

Using the PTB Output to Answer Patient Questions and to Support Clinical Decisions

Consider the following vignettes in which a clinician might respond to a patient’s questions using output from the PTB Method. We answer the questions first for a patient with PTSD who has experienced severe interpersonal violence in the past, and then for a patient who has PTSD but has had less severe interpersonal violence in the past.

High Interpersonal Violence

PATIENT 1: I hear that therapy doesn’t often work– is it even worth my time?

CLINICIAN: Studies show that it is worth your time. Without receiving treatment it is highly unlikely that your PTSD symptoms will get better naturally. By participating in treatment you are two to three times more likely to show a significant reduction in symptoms and to no longer meet criteria for PTSD. However, some symptoms may still remain and additional treatment may be warranted in the future.

PATIENT 2: What kind of improvement can I expect after receiving treatment?

CLINICIAN: On this measure of PTSD symptom severity you scored a 71, which is considered to reflect severe PTSD. Research suggests that after receiving treatment, you can reduce this by as much as 24 points, bringing this score down closer to what is considered mild to moderate severity. This means that while treatment may not make all of the symptoms go away, you should experience a significant improvement.

PATIENT 3: Which treatment is better, PCT or TARGET?

CLINICIAN: The research suggests that either of these treatments can reduce your symptoms by as much as 50%, with a good chance of no longer having a diagnosis of PTSD. However, some symptoms may still remain and additional treatment may be warranted in the future.

Low Interpersonal Violence

PATIENT 4: This is a really tough time for me right now. My schedule is very hectic. Is it imperative that I receive treatment for these symptoms now – or could I wait this out a bit?

CLINICIAN: Without treatment, your symptoms are expected to decrease by about a quarter over the course of a few months. We call this natural recovery. However, there is still a good chance (about 75%) that you will still have PTSD. You can double the odds of recovering from PTSD if you choose to receive therapy.

PATIENT 5: Based on the research, which treatment gives me the greatest odds of recovery, PCT or TARGET?

CLINICIAN: Although PCT and TARGET both are expected to significantly improve your symptoms, research suggests that TARGET can lead to about a 50% greater symptom reduction and a 10% greater likelihood of no longer having PTSD compared to PCT.

Discussion

Using the PTB method with the dataset from an RCT study of PTSD treatment provided a more nuanced picture than did effect sizes alone. For example, we see that patients with histories of multiple types of interpersonal violence show negligible natural recovery in PTSD without treatment, but show a substantial amount of change when receiving treatment that addresses either emotion regulation (TARGET) or interpersonal relationships (PCT). This finding is consistent with prior results showing that receiving professional services (Song, 2012), and specifically those that are associated with a strong working alliance (Smith et al., 2012)–as was shown to be the case for both TARGET and PCT (Ford et al., 2011)—is related to successful recovery from the sequelae of severe interpersonal violence.

Also interesting is that patients with low interpersonal violence in the waitlist control condition showed comparable improvement rates to those receiving treatment; however, a greater proportion were expected to be in the clinical range post-treatment, suggesting that treatment may be necessary to achieve clinically significant outcomes with patients who have experienced some—but not multiple types of—interpersonal violence despite their tendency to improve naturally (Song, 2012).

Furthermore, the PTB method provides output that is potentially more relevant to patients and clinicians than traditional estimates of effect sizes. Cohen’s d, NNT, and ARR, while useful metrics in some contexts (such as comparative effectiveness studies), are aggregate statistics of therapeutic outcome or treatment response in general, relative to a control group of patients, and do not readily lend themselves to personalized applications. PTB output, on the other hand, provides a probability estimate that an individual patient will achieve a particular outcome in absolute terms. One advantage of this is that local clinics that routinely track patient outcomes can use the PTB method to disclose the expected benefit of their services.

The PTB method has the potential to provide researchers and clinicians with a practical and interpretable means of comparing treatment options for individuals whose response and outcome to treatment may differ substantially. Applied on a larger scale, the PTB method could provide a way to gauge the value of providing a range of treatments to patients with PTSD or other mental health problems and different prognostic characteristics including but not limited to the severity of interpersonal violence variable used in the current example. For example, the PTB method may be instrumental in capturing the differential effects of treatments based on differences in culture, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, all characteristics with potential to moderate treatment response and/or outcome. PTB results could provide a basis for empirically predicting different patients’ likely response to and outcome in a variety of psychotherapeutic treatments. In future studies, therefore, it will be important to collect data on the ease with which patients are able to understand PTB output and its acceptability and utility as a patient-centered decision-support tool. Finally, it will also be important to apply the PTB method to outcomes other than symptom reduction (e.g., days of missed work, quality of life) that may be important to patients and their families.

For successful application of the PTB method to the mental health field, it will be necessary to achieve buy-in from both clinical researchers and practitioners and to cultivate a working bridge between research and practice that can facilitate dissemination of PTB charts from clinical trials to working clinics. While publication in scientific journals is one way for clinical researchers to disseminate this information, other means may also prove viable and successful and may emerge from the fast growing field of implementation science.

References

- Beidas RS, Lindhiem O, Brodman DM, Swan A, Carper M, Cummings C, Sherrill J. A probabilistic and individualized approach for predicting treatment gains: An extension and application to anxiety disordered youth. Behavior Therapy. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, et al. The development of a Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8(1):75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill SP, Rothbaum BO, Resick PA, Folette V. Cognitive behavior therapy for adults. In: Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen JA, editors. Effective treatments for PTSD. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2009. pp. 139–222. [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Bernstein A, Daleiden EL. Driving with roadmaps and dashboards: Using information resources to structure the decision models in service organizations. Adminstration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. Special Issue: Improving mental health services. 2008;35(1–2):114–123. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0151-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christon LM, McLeod BD, Jensen-Doss A. Evidence-based assessment meets evidence-based treatment: An approach to science-informed case conceptualization. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Cook J, Schnurr PP, Foa EB. Bridging the gap between posttraumatic stress disorder research and clinical practice: the example of exposure therapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2004;41(4):374–387. [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Russo E. A trauma-focused, present-centered, emotion self-regulation approach to integrated treatment for PTSD and addiction. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 2006;60:335–355. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2006.60.4.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Smith SF. Complex PTSD in trauma-exposed adults receiving public outpatient substance abuse disorder treatment. Addiction Research & Theory. 2008;16:193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Elhai JD, Connor DF, Frueh BC. Poly-victimization and risk of posttraumatic, depressive, and substance use disorders and involvement in delinquency in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46(6):545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Steinberg KL, Zhang W. A randomized clinical trial comparing affect regulation and social problem-solving psychotherapies for mothers with violence-related PTSD. Behavior Therapy. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SE. The diagnosis of mental disorders: the problem of reification. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:155–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59(1):12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaycox LH, Foa EB. Obstacles in implementing exposure therapy for PTSD: Case discussions and practical solutions. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 1996;3:176–184. [Google Scholar]

- Koster EHW, Defreyne K, Putter L, Vanden Bogaerde A. Een nieuwe methode om de slaagkans van therapie bespreekbaar te maken [A new method for the success rate of therapy] Psychopraktijk. 2013;5(3):14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Frank E, Kupfer DJ. How to assess the clinical impact of treatments on patients, rather than the statistical impact of treatments on measures. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2011;20(2):63–72. doi: 10.1002/mpr.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindhiem O, Kolko DJ, Cheng Y. Predicting Psychotherapy Benefit: A Probabilistic and Individualized Approach. Behavior Therapy. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonagh A, Friedman M, McHugo G, Ford J, Sengupta A, Mueser K, Descamps M. Randomized trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in adult female survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(3):515–524. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonagh-Coyle A, Friedman MJ, McHugo GJ, Ford JD, Sengupta A, Mueser KT, et al. Randomized trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic PTSD in adult female survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:515–524. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson KW, Krueger CE, Wilson C. Relationships between maternal emotion regulation, parenting, and children's executive functioning in families exposed to intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2012;27(17):3532–3550. doi: 10.1177/0886260512445385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PN, Gamble SA, Cort NA, Ward EA, He H, Talbot NL. Attachment and alliance in the treatment of depressed, sexually abused women. Depression and Anxiety. 2012;29(2):123–130. doi: 10.1002/da.20913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song LY. Service utilization, perceived changes of self, and life satisfaction among women who experienced intimate partner abuse: the mediation effect of empowerment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2012;27(6):1112–1136. doi: 10.1177/0886260511424495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Keane TM, Davidson JR. Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;13:132–115. doi: 10.1002/da.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngstrom EA, Choukas-Bradley S, Calhoun CD, Jensen-Doss A. Clinical guide to the evidence-based assessment approach to diagnosis and treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. (in press). [Google Scholar]