Abstract

Context:

Lipodystrophies are extreme forms of metabolic syndrome. Metreleptin was approved in the United States for generalized lipodystrophy (GLD) but not partial lipodystrophy (PLD).

Objective:

The objective of the study was to test metreleptin's efficacy in PLD vs GLD and find predictors for treatment response.

Design:

This was a prospective, single-arm, open-label study since 2000 with continuous enrollment. Current analysis included metreleptin treatment for 6 months or longer as of January 2014.

Setting:

The study was conducted at the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, Maryland).

Participants:

Patients clinically diagnosed with lipodystrophy, leptin less than 8 ng/mL (males) or less than 12 (females), age older than 6 months, and one or more metabolic abnormalities (diabetes, insulin resistance, or hypertriglyceridemia) participated in the study.

Intervention:

The interventions included sc metreleptin injections (0.06–0.24 mg/kg · d).

Main Outcomes and Measures:

Changes in glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and triglycerides after 6 and 12 months of metreleptin were measured.

Results:

Baseline metabolic parameters were similar in 55 GLD [HbA1c 8.4% ± 2.3%; triglycerides, geometric mean (25th, 75th percentile), 467 mg/dL (200, 847)] and 31 PLD patients [HbA1c 8.1% ± 2.2%, triglycerides 483 mg/dL (232, 856)] despite different body fat and endogenous leptin. At 12 months, metreleptin decreased HbA1c (to 6.4% ± 1.5%, GLD, P < .001; 7.3% ± 1.6%, PLD, P = .004) and triglycerides [to 180 mg/dL (106, 312), GLD, P < .001; 326 mg/dL (175, 478), PLD, P = .02]. HbA1c and triglyceride changes over time significantly differed between GLD and PLD. In subgroup analyses, metreleptin improved HbA1c and triglycerides in all GLD subgroups except those with baseline triglycerides less than 300 mg/dL and all PLD subgroups except baseline triglycerides less than 500 mg/dL, HbA1c less than 8%, or endogenous leptin greater than 4 ng/mL.

Conclusions:

In addition to its proven efficacy in GLD, metreleptin is effective in selected PLD patients with severe metabolic derangements or low leptin.

The cluster of conditions that defines metabolic syndrome, namely dyslipidemia with high triglycerides and low high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), dysglycemia, hypertension, and central obesity, has become a worldwide epidemic. Recent criteria define the syndrome as three of five of the above criteria, no longer enforcing an obligatory increased waist circumference or central obesity for diagnosis (1). The characteristic pattern of metabolic syndrome-associated dyslipidemia as well as insulin resistance are also hallmarks of a group of rare disorders called lipodystrophies. These are characterized by either inherited or acquired loss of sc fat, extreme insulin resistance, severe hypertriglyceridemia, and low HDL-C (2, 3) and hence represent an extreme variant of metabolic syndrome.

Generalized lipodystrophy (GLD) is associated with whole-body sc adipose loss, whereas depot-specific adipose loss suggests partial lipodystrophy (PLD). Low adipose storage results in very low levels of the adipokine leptin in GLD, and variably higher leptin in PLD (4), leading to altered hunger-satiety signals to the central nervous system and hyperphagia. The caloric surplus is accumulated as ectopic fat in the liver and muscle, causing severe insulin resistance and diabetes with high insulin requirements, and hypertriglyceridemia, which may be severe enough to induce recurrent pancreatitis (5). Patients with lipodystrophy also present with a characteristic physical appearance, fatty liver disease (6), a spectrum of cardiomyopathies (7), and proteinuric nephropathies (8), and insulin resistance-associated hyperandrogenism (9–11).

Leptin administration in a mouse model of GLD was a turning point in lipodystrophy management (12). It resulted in dramatic improvement in metabolic abnormalities in the mouse, forming a rationale for studying the effects of metreleptin, a recombinant analog of human leptin, in patients. Prior to metreleptin, lipodystrophic patients were treated with conventional high-dose antidiabetic and lipid-lowering drugs, mostly without achieving adequate control of their severe disease. Studies conducted at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center showed that metreleptin treatment reduced food intake (13) and substantially improved most metabolic abnormalities in lipodystrophy patients, studied as a cohort of all forms with no distinction between lipodystrophy subtypes (14, 15). In GLD, metreleptin dramatically decreased hypertriglyceridemia and markedly improved glycemic parameters, including fasting glucose, glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), and insulin resistance (16–19). It also improved ectopic lipid storage (20), hyperfiltration and proteinuria (8), and steatohepatitis (6). In PLD, metreleptin ameliorated hypertriglyceridemia; however, its effects on hyperglycemia have been conflicting (17, 21–23). Of note, due to the rarity of lipodystrophy, all studies have enrolled very small cohorts of patients (n = 7–36 GLD, n = 6–24 PLD). Nevertheless, given the convincing efficacy data in GLD, the US Food and Drug Administration approved metreleptin's use in GLD in February 2014. However, metreleptin was not approved for use in patients with PLD, in whom the benefits were not as well established.

The overall goal of this study was to describe baseline characteristics and response to metreleptin treatment in PLD as compared with GLD. We also looked for predictors of response to metreleptin by asking whether the lipodystrophy type (GLD vs PLD) or the endogenous leptin level better predicts the response to metreleptin and is there a subgroup of patients that best responds to metreleptin.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This was a prospective, one-arm, open-label study evaluating effects of metreleptin in lipodystrophy. The study was conducted at the NIH (number NCT00025883) and was approved by the institutional review board of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Written informed consent was obtained from patients or their legal guardians. Assent was obtained from participants younger than 18 years of age. This study has been ongoing at the NIH since 2000, with continuous enrollment and variable duration of follow-up. The current analysis includes GLD and PLD patients treated with metreleptin for 6 months or longer as of January 2014.

Patients

Inclusion criteria were a clinical diagnosis of lipodystrophy, low serum leptin at study enrollment (<8 ng/mL in males, <12 ng/mL in females), age older than 6 months, and one or more metabolic abnormalities including diabetes mellitus defined per the 2007 American Diabetes Association criteria (24), insulin resistance [fasting insulin ≥ 30 μU/mL (215 pmol/L)], or hypertriglyceridemia (fasting triglyceride > 200 mg/dL). Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, infectious liver disease or alcohol abuse, HIV infection, active tuberculosis, hypersensitivity to Escherichia coli-derived proteins, use of anorexigenic medications, and psychiatric disorders or other diseases impeding competence or compliance.

Study intervention and follow-up

Patients received self-administered sc metreleptin injections in one to two daily doses ranging from 0.06 to 0.24 mg/kg · d. Doses were adjusted to achieve metabolic control and avoid excessive weight loss. Antihyperglycemic and lipid-lowering regimens were modified if clinically indicated. One hundred three patients were enrolled. We excluded from analysis four patients with atypical progeroid lipodystrophy, one patient with no baseline data, one who died from pancreatitis and sepsis 3.5 months after the start of metreleptin treatment, one who was taken off metreleptin for a serious adverse event before any follow-up was obtained, and 10 who had not yet reached 6 months of metreleptin at the time of the data cut.

Outcome measures

Clinical values were collected at baseline, 6 months (range 4–8 mo), and 12 months (range 10–15 mo) after metreleptin initiation. Outcomes included serum leptin, anthropometric parameters [body mass index (BMI) and body fat percentage], glycemic variables (serum glucose, HbA1c, number of antidiabetic and lipid lowering medications, insulin use, and average daily insulin dose among insulin users), and lipids. Blood samples were analyzed using the standard techniques of the NIH Clinical Center laboratory. Leptin was measured by a RIA using a commercial kit (Linco Research). Body fat percentage was measured using whole-body dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA; Hologic QDR 4500; Hologic). The BMI was adjusted for sex and age using SD scores (SDS) derived from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey population normative data (25). For patients younger than age 20 years, SDS are Z-scores (compared with age matched controls). For patients older than age 20 years, SDS are T-scores (compared with 20 y old controls). Compliance was defined as greater than 70% use of metreleptin injections. The following categories were selected for subgroup analysis in GLD and PLD: baseline triglyceride level 300 mg/dL or greater, less than 300, 500 or greater, and less than 500 as well as baseline HbA1c 7% or greater, less than 7, 8 or greater, and less than 8. All GLD patients had leptin levels less than 4 ng/mL except for one with 5.29 ng/mL; therefore, a subgroup analysis for baseline leptin greater than or less than 4 ng/mL was performed in PLD only.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel, GraphPad Prism version 6.01 (GraphPad) and SAS Enterprise Guide version 5.1 (SAS Institute). Baseline characteristics of GLD vs PLD and change in number of antidiabetic medications and insulin use at 0 months vs 12 months on metreleptin were compared using a χ2 test for categorical parameters and unpaired or paired Student's t tests or age- and sex-adjusted analysis of covariance for continuous variables. Triglycerides were log transformed for analyses due to nonnormal distribution in lipodystrophic subjects. The relationship between leptin level and body fat, triglycerides, and HbA1c was assessed by linear regression, with adjustment for age as appropriate. Mixed models were used to analyze the change of selected variables over time in response to metreleptin. Univariate and multivariate analyses were used to assess the influence of lipodystrophy type (generalized vs partial) and baseline leptin as potential predictors of metreleptin response. Results are presented as mean ± SD. Triglycerides are presented as geometric means (25th, 75th percentiles). Values of P < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

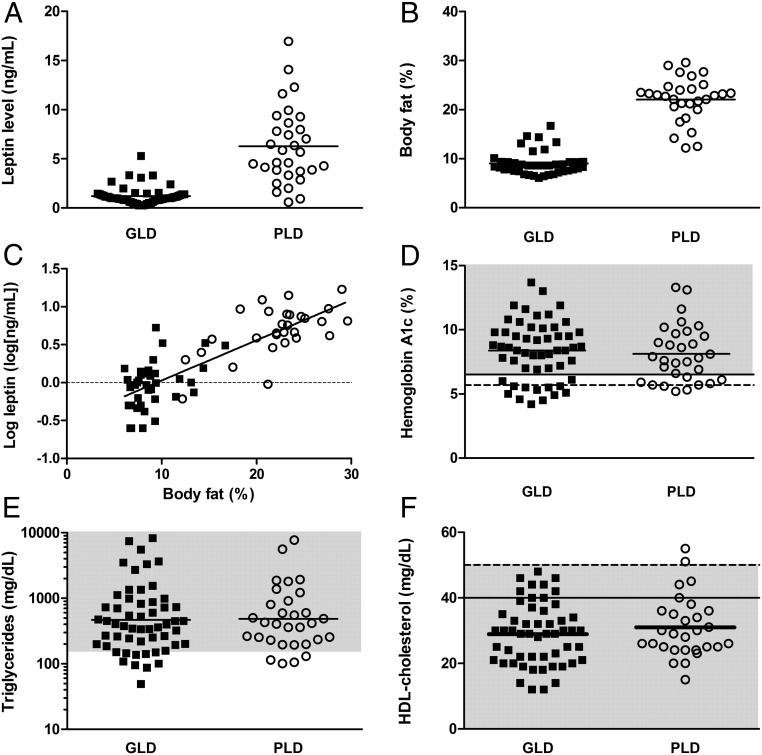

Patients' baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. Fifty-five GLD (39 congenital, 16 acquired) and 31 PLD patients (25 congenital, six acquired) were included in the analysis. There were different sex and age distributions in GLD vs PLD [76% vs 100% females, P = .003, age 18 ± 12 y (range 1.6–68 y) in GLD vs 35 ± 14 (range 11–64 y) in PLD, P < .001]. BMI-SDS and percentage body fat were significantly lower in GLD. Endogenous leptin was lower in GLD (1.13 ± 0.74 ng/mL, range 0.25–5.29 ng/mL) vs PLD (6.23 ± 3.96 ng/mL, range 0.61–16.93 ng/mL) (P < .001), but there was considerable overlap between the two groups. In GLD, leptin levels were similar in males and females (males, 1.08 ± 0.80 ng/mL, n = 13, normal 3.8 ± 1.8 for lean men; females, 1.24 ± 0.93, n = 42, normal 7.4 ± 3.7 for lean women; P = .55) (26). In the full cohort (PLD + GLD), leptin correlated with body fat (r2 = 0.7, P < .001), similar to the general population (27).

Table 1.

Baseline Values in Patients With Generalized vs Partial Lipodystrophy

| Clinical Values | Generalized Lipodystrophy (n = 55) | Partial Lipodystrophy (n = 31) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic parameters | |||

| Females | 42 (76%) | 31 (100%) | .003 |

| Age, y | 18 (12) | 35 (14) | <.001 |

| Pediatric patients, aged <20 y, % | 42 (76%) | 7 (23%) | <.001 |

| Anthropometric parameters | |||

| BMI-SDS | 0.26 (0.98) | 0.66 (0.70) | .004 |

| Percentage body fat | 9 (2) | 22 (4) | <.001 |

| Leptin, ng/mL | 1.13 (0.74) | 6.23 (3.96) | <.001 |

| Glycemic parameters | |||

| Glucose, mg/dL | 180 (80) | 182 (87) | .50 |

| HbA1c, % | 8.4 (2.3) | 8.1 (2.2) | .65 |

| Fasting insulin, μU/mLa | 122 (318) | 82 (157) | .46 |

| C-peptide, ng/mL | 5.61 (4.03) | 3.56 (2.27) | .21 |

| Antidiabetic medications per patient | 1.13 (0.70) | 1.79 (0.68) | <.001 |

| Insulin users | |||

| Yes | 30 (56%) | 15 (52%) | .82 |

| No | 24 (44%) | 14 (48%) | |

| Daily total insulin units per patient | 625 (1099) | 278 (214) | .12 |

| Lipid parameters | |||

| Lipid-lowering medications per patient | 0.61 (0.84) | 1.07 (1.04) | .05 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 214 (110) | 235 (147) | .18 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 467 (200 847) | 483 (232, 856) | .23 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 29 (9) | 31 (9) | .33 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 104 (50) | 101 (36) | .73 |

| Fat-soluble vitamins | |||

| Vitamin A, μg/dL | 57 (33) (n = 19) | 73 (20) (n = 13) | .34 |

| Vitamin E, mg/L | 26 (32) (n = 20) | 34 (21) (n = 13) | .25 |

| 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, ng/mL | 16 (11) (n = 46) | 23 (13) (n = 29) | .41 |

| PT, sec | 14.2 (1.2) (n = 30) | 13.2 (0.6) (n = 21) | .003 |

| INR | 1.10 (0.14) (n = 22) | 0.98 (0.06) (n = 16) | .01 |

Abbreviations: BMI-SDS, body mass index SD-score; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PT, prothrombin time. Data are mean (SD) or n (percentage). Data are geometric mean (25th, 75th percentiles) for triglycerides.

Fasting insulin levels in both insulin users and nonusers.

Figure 1.

Baseline values in patients with generalized vs partial lipodystrophy. Baseline subject-level data and means in patients with GLD (black squares) and PLD (open circles). Leptin levels (A) and body fat (B) were lower in GLD, and leptin was correlated with body fat (C) in both groups. HbA1c (D), triglycerides (E, geometric mean), and HDL-C were similar in both groups (high risk ranges shown in gray shading). Cutoffs for diabetes (solid line), prediabetes (dashed line) (C), and high-risk HDL-C in men (dashed line) and women (solid line) (F) are shown as horizontal lines.

Despite differences in body fat and leptin levels, metabolic parameters including glycemic values and lipids were similar in GLD and PLD. In the full cohort, age-adjusted linear regression showed no correlation between baseline leptin and triglycerides (P = .96) or between leptin and HbA1c (P = .92).

Mean levels of the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, and E were higher in PLD, consistent with higher fat storage; however, these differences were not statistically significant. The prothrombin time and international ratio (INR), representing vitamin K function, were significantly lower in PLD, also consistent with more adipose storage.

Response to treatment with metreleptin

Changes in metabolic parameters and use of antidiabetic or lipid-lowering medications in response to metreleptin are shown in Table 2, Figure 2, and Supplemental Table 1. Over 12 months of metreleptin treatment, BMI-SDS significantly decreased in both GLD and PLD but remained within the normal range. Body fat was similar at baseline and 12 months in GLD but showed a nonsignificant downward trend in PLD. Eighty-eight percent and 82% of GLD patients were compliant to treatment at 6 and 12 months, respectively. Eighty percent and 75% of PLD patients were compliant to treatment at 6 and 12 months, respectively. HbA1c fell from 8.4% ± 2.3% at baseline to 6.4% ± 1.5% at 12 months in GLD (P < .001 for change in HbA1c over time) and from 8.1% ± 2.2% to 7.3% ± 1.6% in PLD (P = .004). Improvements in HbA1c with metreleptin were significantly greater in GLD compared with PLD. Similarly, fasting glucose decreased in both GLD and PLD (180 ± 80 mg/dL to 121 ± 60 mg/dL in GLD, 182 ± 87 mg/dL to 132 ± 54 mg/dL in PLD, P < .001).

Table 2.

Clinical Values in Generalized and Partial Lipodystrophy Patients Treated With Metreleptin

| Clinical Values | Generalized Lipodystrophy |

Partial Lipodystrophy |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 mo (n = 55) | 6 mo (n = 49) | 12 mo (n = 52) | P Value | 0 mo (n = 31) | 6 mo (n = 25) | 12 mo (n = 28) | P Value | |

| Anthropometric parameters | ||||||||

| BMI-SDS | 0.26 (0.98) | −0.24 (1.35) | −0.33 (1.20) | <.001 | 0.66 (0.70) | 0.49 (0.76) | 0.50 (0.76) | .01 |

| Percentage body fat | 9 (2) | 8 (2) | 8 (2) | .09 | 22 (4) | 20 (4) | 18 (3) | .07 |

| Glycemic parameters | ||||||||

| Glucose, mg/dL | 180 (80) | 124 (50) | 121 (60) | <.001 | 182 (87) | 137 (43) | 132 (54) | <.001 |

| HbA1c, % | 8.4 (2.3) | 6.6 (1.7) | 6.4 (1.5) | <.001 | 8.1 (2.2) | 7.2 (1.2) | 7.3 (1.6) | .004 |

| C-peptide, ng/mL | 5.61 (4.03) | 4.23 (2.77) | 4.48 (3.09) | .01 | 3.56 (2.27) | 3.76 (1.96) | 3.41 (1.94) | .26 |

| Antidiabetic medications per patient | 1.13 (0.70) | 0.65 (0.62) | <.001 | 1.79 (0.68) | 1.74 (0.81) | .42 | ||

| Insulin use | ||||||||

| Yes | 28 (55%) | 11 (21%) | <.001 | 14 (52%) | 14 (52%) | 1.00 | ||

| No | 23 (45%) | 41 (79%) | 13 (48%) | 13 (48%) | ||||

| Daily total insulin units per patient | 625 (1099) | 103 (398) | .009 | 278 (214) | 175 (131) | .07 | ||

| Lipid parameters | ||||||||

| Lipid-lowering medications per patient | 0.61 (0.84) | 0.27 (0.53) | <.001 | 1.07 (1.04) | 1.08 (1.09) | 1.00 | ||

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 214 (110) | 146 (58) | 146 (38) | <.001 | 235 (147) | 188 (45) | 196 (73) | .06 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 467 (200 847) | 198 (122, 283) | 180 (106, 312) | <.001 | 483 (232, 856) | 339 (211, 530) | 326 (175, 478) | .02 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 29 (9) | 30 (8) | 30 (7) | .78 | 31 (9) | 33 (7) | 32 (9) | .32 |

Abbreviation: BMI-SDS, body mass index SD-score. Data are mean (SD), or n (percentage). Data are geometric mean (25th, 75th percentiles) for triglycerides. P value is for the effect of metreleptin over time.

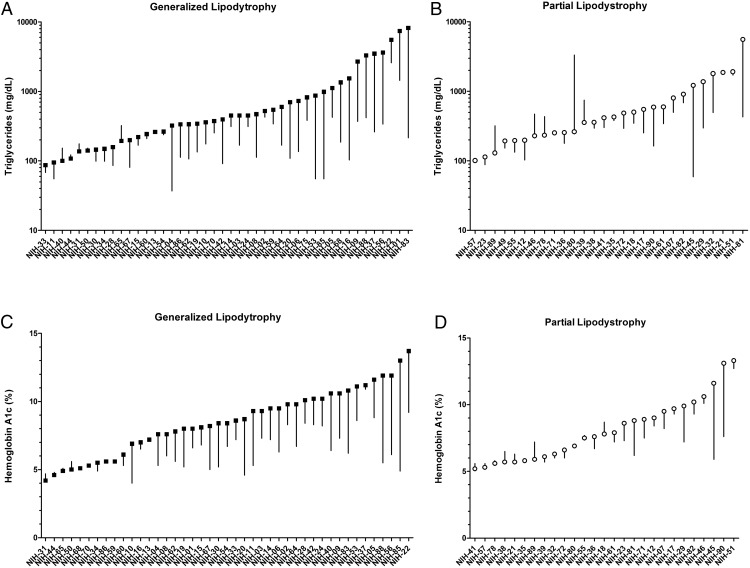

Figure 2.

Clinical values in generalized and partial lipodystrophy patients treated with metreleptin. Waterfall plots showing change in triglycerides and HbA1c in individual subjects (subject identifier on x-axis) after 1 year of metreleptin in GLD (A and C, black squares) and PLD (B and D, open circles) patients.

The number of antidiabetic and lipid-lowering medications per patient, rate of insulin users, and total daily insulin dose were significantly lower in GLD after 12 months on metreleptin. These measures did not change in PLD, although there was a trend for lower daily insulin dosing (278 ± 214 U at 0 mo to 175 ± 131 at 12 mo, P = .07). In GLD, 14 patients stopped or reduced the dose of lipid-lowering medications, six had no change, and none increased the dose or number of medications. In PLD, two patients stopped or reduced the dose of lipid-lowering medications, 12 had no change, and two added a lipid-lowering medication to their baseline regimen. Metreleptin resulted in significant reductions in triglycerides in GLD [geometric mean (25th, 75th percentiles), 467 mg/dL (200, 847) at baseline to 180 mg/dL (106, 312) at 12 mo, P < .001] and PLD (483 mg/dL (232, 856) at baseline to 326 mg/dL (175, 478) at 12 months, P = .02). There was a decrease in total cholesterol in GLD (P < .001) and PLD (P = .06), whereas HDL-C did not change. Most of the change in HbA1c and triglycerides was already noted after 6 months of treatment. Neither of these outcomes was different at 6 vs 12 months on post hoc testing in both GLD and PLD. Both HbA1c change and triglyceride change over time were significantly different in PLD vs GLD patients treated with metreleptin (P = .0004 and P = .0272, respectively).

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses are shown in Tables 3 and 4. The decrease in HbA1c and in triglycerides in response to metreleptin was statistically significant in PLD patients with the following characteristics: baseline triglycerides 300 mg/dL or greater or 500 mg/dL or greater, baseline HbA1c 7% or greater or 8% or greater, and baseline leptin less than 4 ng/mL. In contrast, metreleptin did not lower HbA1c or triglycerides in PLD patients with baseline triglycerides less than 300 mg/dL or less than 500 mg/dL, baseline HbA1c less than 8%, or baseline leptin 4 ng/mL or greater.

Table 3.

Subgroup Analysis of the Change in HbA1c in Response to Metreleptin Treatment in GLD and PLD Patients

| Subgroup | Generalized Lipodystrophy |

Partial Lipodystrophy |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 mo HbA1c, % | 6 mo HbA1c, % | 12 mo HbA1c, % | P Value | 0 mo HbA1c, % | 6 mo HbA1c, % | 12 mo HbA1c, % | P Value | |

| Baseline HbA1c > 8% (GLD, n = 34; PLD, n = 14) | 9.8 (1.4) | 7.1 (1.8) | 6.9 (1.5) | <.001 | 10.1 (1.6) | 7.9 (1.2) | 8.3 (1.9) | <.001 |

| Baseline HbA1c > 7% (GLD, n = 40; PLD, n = 20) | 9.4 (1.6) | 7.0 (1.7) | 6.8 (1.5) | <.001 | 9.3 (1.8) | 7.8 (1.1) | 8.1 (1.7) | .002 |

| Baseline HbA1c < 8% (GLD, n = 22; PLD, n = 17) | 6.1 (1.2) | 5.6 (1.1) | 5.5 (0.8) | .002 | 6.5 (0.9) | 6.8 (1.2) | 6.5 (0.9) | .81 |

| Baseline leptin < 4 ng/mL (PLD, n = 10) | 8.8 (2.6) | 7.1 (1.7) | 7.3 (2.2) | .04 | ||||

| Baseline leptin > 4 ng/mL (PLD, n = 21) | 7.8 (2.0) | 7.3 (1.1) | 7.3 (1.4) | .15 | ||||

Data are mean (SD). P value is for the effect of metreleptin over time.

Table 4.

Subgroup Analysis of the Change in Triglycerides in Response to Metreleptin Treatment in GLD and PLD Patients

| Subgroup | Generalized Lipodystrophy |

Partial Lipodystrophy |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 mo Triglycerides, mg/dL | 6 mo Triglycerides, mg/dL | 12 mo Triglycerides, mg/dL | P Value | 0 mo Triglycerides, mg/dL | 6 mo Triglycerides, mg/dL | 12 mo Triglycerides, mg/dL | P Value | |

| Baseline triglycerides > 300 mg/dL (GLD, n = 34; PLD, n = 19) | 912 (449, 1347) | 257 (148, 334) | 208 (113, 341) | <.001 | 926 (457, 1590) | 410 (238, 596) | 396 (295, 498) | .002 |

| Baseline triglycerides > 500 mg/dL (GLD, n = 22; PLD, n = 13) | 1455 (728, 3153) | 308 (150, 597) | 264 (144, 410) | <.001 | 1309 (598, 1863) | 429 (223, 623) | 405 (285, 545) | .001 |

| Baseline triglycerides < 300 mg/dL (GLD, n = 21; PLD, n = 12) | 158 (137, 220) | 131 (97, 205) | 135 (93, 193) | .28 | 179 (126, 239) | 254 (173, 287) | 241 (118, 377) | .51 |

| Baseline triglycerides < 500 mg/dL (GLD, n = 33; PLD, n = 18) | 219 (149, 343) | 150 (123, 230) | 138 (99, 201) | <.001 | 235 (194, 359) | 290 (206, 409) | 277 (148, 392) | .71 |

| Baseline leptin < 4 ng/mL (PLD, n = 10) | 978 (513, 1848) | 429 (215, 629) | 342 (179, 498) | .04 | ||||

| Baseline leptin > 4 ng/mL (PLD, n = 21) | 345 (198, 503) | 297 (209, 380) | 318 (200, 432) | .42 | ||||

Data are geometric mean (25th, 75th percentiles). P value is for the effect of metreleptin over time.

In GLD, the decrease in HbA1c with metreleptin was statistically significant in all subgroups. The metreleptin-induced decrease in triglycerides was statistically significant in all subgroups except in patients with baseline triglycerides less than 300 mg/dL.

Predictors of response to metreleptin

Univariate analyses in the full cohort showed that both lipodystrophy type (generalized vs partial) and the baseline endogenous leptin level predicted the triglyceride response to metreleptin (P = .006 for lipodystrophy type, P < .001 for baseline leptin). Lipodystrophy type was significant (P = .001) and baseline leptin was borderline significant (P = .05) in predicting the HbA1c response to metreleptin. Sex, age, race, compliance to metreleptin, baseline BMI-Z, and BMI-Z change on treatment were not significant predictors of either triglyceride or HbA1c response to metreleptin. Multivariate analyses including both lipodystrophy type and baseline leptin as predictors showed that lipodystrophy type was significant in predicting HbA1c response (P = .02 for lipodystrophy type, P = .57 for baseline leptin), whereas baseline leptin predicted triglyceride response to metreleptin (P = .20 for lipodystrophy type, P = .03 for baseline leptin).

Adverse events

During 12 months of treatment with metreleptin, 275 adverse events (AEs) occurred, including 21 serious AEs (SAEs) in 10 patients. All SAEs were judged to be unrelated to metreleptin treatment. AEs occurring in at least 5% of patients, and all SAEs, are summarized in Supplemental Table 2. The most common AEs were gastrointestinal (GI) (38% of patients), musculoskeletal (22%), and infections (15%).

Discussion

This work shows that metreleptin is an effective treatment in PLD patients with severe metabolic abnormalities or low endogenous leptin in addition to its proven efficacy in GLD. We have demonstrated this effect in the largest cohort of lipodystrophy patients (both PLD and GLD) studied to date. Specifically, the PLD patients most likely to respond are those with triglycerides greater than 500 mg/dL or HbA1c greater than 8%. There were also significant improvements in HbA1c and triglycerides in PLD patients with endogenous leptin less than 4 ng/mL (comparable with leptin levels seen in GLD), regardless of the severity of their lipid or glucose abnormalities. In addition, there were individual patients who did not meet these criteria who nonetheless showed metabolic improvement with metreleptin.

Patients with lipodystrophy have extreme manifestations of the common, obesity-associated metabolic syndrome. Studies of insulin resistance in patients with obesity-associated metabolic syndrome are hampered by the heterogeneous nature of this condition, which is contributed to by hundreds of genes as well as environmental factors. Lipodystrophy patients, by virtue of their more extreme phenotype, as well as a defined target for intervention (leptin deficiency), serve as models to understand the role of leptin in human energy metabolism. By advancing our understanding of pathways regulating energy metabolism in rare diseases, we can not only develop therapeutics for these rare conditions but also elucidate pathways that may serve as drug targets for more common disorders of insulin resistance. Metreleptin has not been effective in reducing insulin resistance in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes (28), likely due to insensitivity to added, recombinant leptin in patients with already high endogenous leptin produced by large adipose tissue depots. However, metreleptin may have clinical utility in other common disorders, such as patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and relatively low leptin levels (29).

At baseline, PLD patients were older than GLD patients, presumably because metabolic complications of lipodystrophy present at a younger age in GLD. By the time of study enrollment, both groups had comparable metabolic disease severity, showing that, over time, PLD manifestations may be as severe as those seen in GLD. The similarity in baseline metabolic disease is particularly notable, given that, as expected, PLD patients had higher BMI, body fat, and leptin levels than GLD patients. Moreover, there was no correlation between the severity of metabolic disease at baseline and endogenous leptin levels. Of note, our cohort is biased toward more severe metabolic disease in both GLD and PLD due to study inclusion criteria; however, the PLD cohort is likely to be more biased because it is not uncommon for PLD patients to present with the characteristic physical phenotype but only minimal metabolic derangements.

Given the inherent differences in body fat in GLD and PLD, we hypothesized that fat-soluble vitamins would be lower in GLD. Consistent with this, all vitamin levels were higher in PLD patients, although only prothrombin time and INR (markers of vitamin K) achieved statistical significance. The failure to detect significant differences in vitamins A, D, and E may be attributable to small sample size; however, none of the differences in fat-soluble vitamins appeared to be clinically significant. In fact, prior studies have shown elevated bone mineral content despite low vitamin D stores in congenital generalized lipodystrophy (30).

In studying predictors of response to metreleptin, we focused on hypertriglyceridemia and diabetes, which are major sources of morbidity and mortality in this population and are difficult to control with conventional treatments. Our findings indicate significant improvements in these values in response to metreleptin in both GLD and PLD, with much of the effect seen after 6 months of treatment. With metreleptin, GLD patients required significantly less pharmacological intervention to achieve better control of diabetes, whereas PLD patients achieved better control on the same antidiabetic regimen. The dramatic 73% reduction in triglycerides and 2% point reduction in HbA1c in GLD are consistent with prior reports (14–19, 21–23). In PLD, metreleptin decreased triglycerides by 54% and HbA1c by 0.8%. Two prior small studies of PLD [n = 6 from the NIH, a subgroup of the current analyses (22) and n = 24 from University of Texas Southwestern (23)] showed improvements in hypertriglyceridemia but no change in HbA1c with metreleptin. The Texas cohort had much milder metabolic abnormalities at baseline compared with the NIH subjects (mean HbA1c 6.5% ± 1.7%, median triglycerides 287 mg/dL), likely explaining the lack of significant metreleptin response. Moreover, a post hoc analysis of the Texas cohort revealed significant HbA1c lowering in patients with HbA1c greater than 6.5%, supporting the idea that patients with more severe baseline disease are more likely to improve with metreleptin. Overall, our findings indicate significant improvements in hypertriglyceridemia and diabetes in response to metreleptin in both GLD and PLD, with much of the effect seen after 6 months of treatment. The metreleptin-induced 0.8%–2% reduction in HbA1c is comparable with the extent of HbA1c improvement by conventional antidiabetic medications.

In our analysis, metreleptin was not effective in PLD patients with mild disease, namely triglycerides less than 500 mg/dL or HbA1c less than 8%. In contrast, in GLD, metreleptin was effective across a wider range of severity of baseline metabolic derangements. It reduced HbA1c in all analyzed subgroups and ameliorated hypertriglyceridemia in all cases except patients with baseline triglycerides less 300 mg/dL. These findings attest to the need for proper selection of patient populations in whom metreleptin would be effective. In other words, metreleptin is effective not only in GLD but also may be of benefit for PLD patients with severe metabolic abnormalities.

Another predictor for HbA1c and triglyceride response to metreleptin in PLD was the endogenous leptin level at baseline because metreleptin was effective only in patients with very low leptin (<4 ng/mL), comparable with that found in GLD. This brought about a question of the significance of the lipodystrophy type (generalized vs partial) vs the endogenous leptin level in predicting effects of metreleptin on metabolic disease. Univariate and multivariate analyses suggested that lipodystrophy type is significant in predicting HbA1c but not triglyceride response, whereas baseline leptin predicts triglyceride but not HbA1c response to metreleptin. These results should be interpreted cautiously because lipodystrophy type and leptin levels partially cosegregate (GLD overlapping with low leptin and PLD with higher leptin).

Despite the difference in compliance rates between GLD and PLD patients, it was not found to predict the response to treatment. The categorical measurement of compliance (>70% of doses taken) may not have been sensitive enough to detect effects of compliance on metabolic response.

An analysis of risks and benefits must be considered prior to any medication's approval by the US Food and Drug Administration. No SAEs that were judged to be related to treatment occurred in this cohort. During long-term uncontrolled studies of metreleptin in lipodystrophy, the occurrence of three cases of T-cell lymphoma and four cases of neutralizing antibodies to leptin (P.G. and R.J.B., unpublished data) resulted in black box warnings on the metreleptin package insert.

To conclude, we clearly show a beneficial effect of metreleptin on glycemic and lipid measures in both GLD and PLD, especially in a selected cohort of PLD patients with significant metabolic abnormalities. The absolute improvement in metabolic abnormalities in PLD patients should be regarded independently, without a comparison with the somewhat higher efficacy of metreleptin in GLD. Due to the rarity of lipodystrophy, long-term studies powered to detect changes in mortality, cardiovascular, and microvascular disease end points are unlikely to be performed. The clinically and statistically significant effects of metreleptin in PLD shown here will likely affect patient outcomes in long-term surveillance.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the patients with lipodystrophy, the clinical fellows, and the nursing staff at the Clinical Center involved in the care of these patients, and Bristol Myers Squibb and Astra Zeneca for the metreleptin used in this study.

This study had a clinical trial registration number of NCT00025883 registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and by the Inter-Institute Endocrinology Fellowship Program at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AE

- serious adverse event

- GLD

- generalized lipodystrophy

- HbA1c

- glycated hemoglobin A1c

- HDL-C

- high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol

- INR

- international ratio

- PLD

- partial lipodystrophy

- SAE

- serious adverse event

- SDS

- SD score.

References

- 1. Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Joseph J, Shamburek RD, Cochran EK, Gorden P, Brown RJ. Lipid regulation in lipodystrophy versus the obesity-associated metabolic syndrome: the dissociation of HDL-C and triglycerides. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014:jc20141878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Garg A. Clinical review: lipodystrophies: genetic and acquired body fat disorders. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:3313–3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haque WA, Shimomura I, Matsuzawa Y, Garg A. Serum adiponectin and leptin levels in patients with lipodystrophies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moon HS, Dalamaga M, Kim SY, et al. Leptin's role in lipodystrophic and nonlipodystrophic insulin-resistant and diabetic individuals. Endocr Rev. 2013;34:377–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Safar Zadeh E, Lungu AO, Cochran EK, et al. The liver diseases of lipodystrophy: the long-term effect of leptin treatment. J Hepatol. 2013;59:131–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lupsa BC, Sachdev V, Lungu AO, Rosing DR, Gorden P. Cardiomyopathy in congenital and acquired generalized lipodystrophy: a clinical assessment. Medicine (Baltimore). 2010;89:245–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Javor ED, Moran SA, Young JR, et al. Proteinuric nephropathy in acquired and congenital generalized lipodystrophy: baseline characteristics and course during recombinant leptin therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3199–3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lungu AO, Zadeh ES, Goodling A, Cochran E, Gorden P. Insulin resistance is a sufficient basis for hyperandrogenism in lipodystrophic women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:563–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Musso C, Cochran E, Javor E, Young J, Depaoli AM, Gorden P. The long-term effect of recombinant methionyl human leptin therapy on hyperandrogenism and menstrual function in female and pituitary function in male and female hypoleptinemic lipodystrophic patients. Metabolism. 2005;54:255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Musso C, Shawker T, Cochran E, Javor ED, Young J, Gorden P. Clinical evidence that hyperinsulinaemia independent of gonadotropins stimulates ovarian growth. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2005;63:73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shimomura I, Hammer RE, Ikemoto S, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Leptin reverses insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus in mice with congenital lipodystrophy. Nature. 1999;401:73–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McDuffie JR, Riggs PA, Calis KA, et al. Effects of exogenous leptin on satiety and satiation in patients with lipodystrophy and leptin insufficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4258–4263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chan JL, Lutz K, Cochran E, et al. Clinical effects of long-term metreleptin treatment in patients with lipodystrophy. Endocr Pract. 2011;17:922–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oral EA, Simha V, Ruiz E, et al. Leptin-replacement therapy for lipodystrophy. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:570–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Beltrand J, Beregszaszi M, Chevenne D, et al. Metabolic correction induced by leptin replacement treatment in young children with Berardinelli-Seip congenital lipoatrophy. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e291–e296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chong AY, Lupsa BC, Cochran EK, Gorden P. Efficacy of leptin therapy in the different forms of human lipodystrophy. Diabetologia. 2010;53:27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ebihara K, Kusakabe T, Hirata M, et al. Efficacy and safety of leptin-replacement therapy and possible mechanisms of leptin actions in patients with generalized lipodystrophy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:532–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Javor ED, Cochran EK, Musso C, Young JR, Depaoli AM, Gorden P. Long-term efficacy of leptin replacement in patients with generalized lipodystrophy. Diabetes. 2005;54:1994–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Simha V, Szczepaniak LS, Wagner AJ, DePaoli AM, Garg A. Effect of leptin replacement on intrahepatic and intramyocellular lipid content in patients with generalized lipodystrophy. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:30–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guettier JM, Park JY, Cochran EK, et al. Leptin therapy for partial lipodystrophy linked to a PPAR-γ mutation. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2008;68:547–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Park JY, Javor ED, Cochran EK, DePaoli AM, Gorden P. Long-term efficacy of leptin replacement in patients with Dunnigan-type familial partial lipodystrophy. Metabolism. 2007;56:508–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Simha V, Subramanyam L, Szczepaniak L, et al. Comparison of efficacy and safety of leptin replacement therapy in moderately and severely hypoleptinemic patients with familial partial lipodystrophy of the Dunnigan variety. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:785–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes, 2007. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(suppl 1):S4–S41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cole TJ. The LMS method for constructing normalized growth standards. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1990;44:45–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ma Z, Gingerich RL, Santiago JV, Klein S, Smith CH, Landt M. Radioimmunoassay of leptin in human plasma. Clin Chem. 1996;42:942–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Considine RV, Sinha MK, Heiman ML, et al. Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:292–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moon HS, Matarese G, Brennan AM, et al. Efficacy of metreleptin in obese patients with type 2 diabetes: cellular and molecular pathways underlying leptin tolerance. Diabetes. 2011;60:1647–1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Trial identifier. Recombinant Leptin Therapy for Treatment of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH). Accessed February 19, 2015 NCT01679197. www.clinicaltrials.gov.

- 30. Christensen JD, Lungu AO, Cochran E, et al. Bone mineral content in patients with congenital generalized lipodystrophy is unaffected by metreleptin replacement therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E1493–E1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]