Abstract

We examine the prevalence of physical and sexual violence among 1,974 married women from 40 low-income communities in Chennai, India. We found a 99% and 75% lifetime prevalence of physical abuse and forced sex, respectively, while 65% of women experienced more than five episodes of physical abuse in the three months preceding the survey. Factors associated with violence after multivariate adjustment included elementary/middle school education and variables suggesting economic insecurity. These domestic violence rates exceed those in prior Indian reports, suggesting women in slums may be at increased risk for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

Keywords: violence, India, forced sex, HIV/AIDS

INTRODUCTION

Domestic violence is a major public health issue worldwide (Heise et al., 1994), resulting in multiple adverse health consequences including physical trauma, chronic pain, depression, gastrointestinal and reproductive disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Campbell et al., 2000; Campbell, 2002). It may also be a crucial component of gender inequality accelerating the spread of HIV among women in developing countries (Farmer et al., 1996; United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS et al., 2004). Domestic violence can increase HIV risk by limiting a woman’s ability to discuss marital infidelity, negotiate condom use, and refuse sexual intercourse (Go et al., 2003). Numerous studies from both developing and developed countries have shown that women with histories of physical abuse, sexual coercion, and rape have higher rates of HIV (Dunkle et al., 2004a; Irwin et al., 1995; Kimerling et al., 1999; Maman et al., 2002; van der Straten et al., 1995; Wingood & DiClemente, 1998; Wyatt et al., 2002), as well as other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (Kenney et al., 1998; Wingood & DiClemente, 1998).

In India, the HIV epidemic was initially restricted to “high-risk” groups such as female sex workers and truck drivers (Bollinger et al., 1995; Mehendale et al., 1996; Simoes et al., 1987), but more recent studies have noted that an increasing proportion of HIV infected women are married and monogamous (Gangakhedkar et al., 1997; Newmann et al., 2000; Panda et al., 2000; Rodrigues et al., 1995). A report from South India found that 95% of HIV-infected women were currently or previously married, and 88% reported a history of monogamy, implying that most were infected by their husbands (Newmann et al., 2000). In this context, “classic” behaviors associated with HIV transmission (such as multiple sexual partners, injection drug use, or blood transfusions) need to be redefined to capture the social factors such as domestic violence which may increase risk of infection for married women in India today.

Previous studies from India assessing the prevalence of, and risk factors for, domestic violence have focused mostly on rural populations (Jejeebhoy, 1998; Jejeebhoy & Cook, 1997; Koenig et al., 2004; Mahajan, 1990; Rao, 1997). The few available estimates in urban settings (Jeyaseelan et al., 2004) have not specifically evaluated slum-dwelling communities, which comprise an increasing proportion of the urban population in India. Also, while most prior studies evaluate rates of physical abuse, few capture data regarding sexual violence in the household (Koenig et al., 2004), an increasingly important issue in the era of HIV. This paper reports the prevalence of various forms of domestic violence, attitudes of women towards such violence, and factors associated with its occurrence among slum dwellers in Chennai, India.

METHODS

Setting And Study Population

This study was conducted in Chennai, the capital city of Tamil Nadu, and the fourth most populous city in India. While Tamil Nadu’s development indicators are relatively better than many other Indian states, it still has significant levels of socioeconomic deprivation, as more than one-fifth of people are below the poverty line and one-fourth are illiterate (Government of Tamil Nadu, 2003; Tamil Nadu Ministry of Home Affairs, 2001). Tamil Nadu is also one of six high HIV prevalence states in India, as reported by the National AIDS Control Organization of India (National AIDS Control Organization of India, 2006).

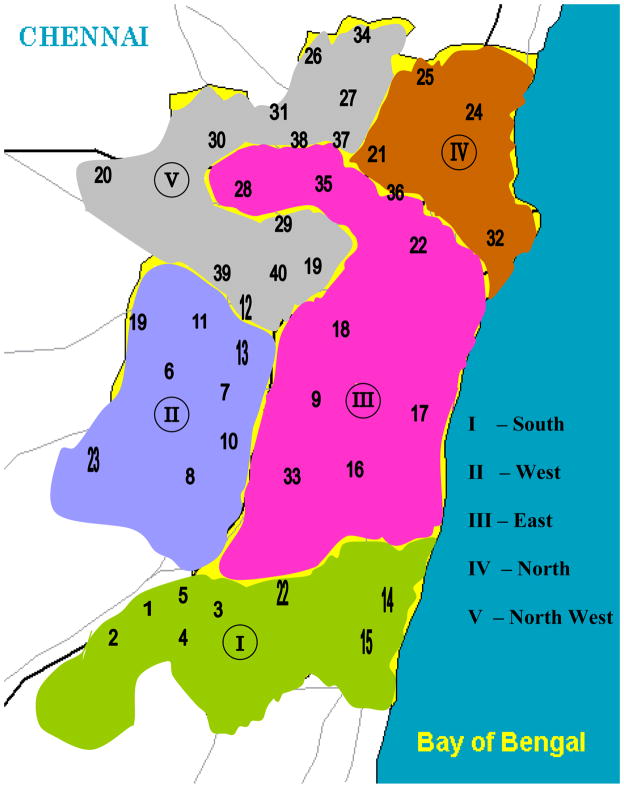

This survey focused on 40 low-income communities with fairly even distribution over the Chennai metropolitan area (Figure 1). The participants live in housing structures ranging from hutments/shacks to chawls (small single room dwellings made of cement) to low-income government housing. Approximately 90% of the study participants had an income less than INR 2000 (USD 44) per month. On a daily basis, many face problems common to the urban poor in India: high-density settlements, cramped living spaces, instability of housing structures, marginal living locations (right next to fetid rivers, railroad tracks, and trash dumps), and lack of frequent access to potable water, electricity and appropriate sanitation facilities.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Survey Implementation Sites Over the Chennai Metropolitan Area

Study Design And Data Collection

While screening participants for a behavioral intervention trial in the slums of Chennai, intimate partner violence emerged as a critical issue in these communities. Briefly, the intervention trial sought to evaluate the role of a community-based popular opinion leader approach to alter risk-taking behavior among “wine-shop” (bar) patrons and the female sex workers who labor within close proximity of these shops (NIMH Prevention Trial Group, 2007). The plan for a study of domestic violence in these communities was presented and discussed at a meeting of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the YRG Centre for AIDS Research and Education (YRG CARE). This IRB is officially registered, follows international guidelines for human subjects research, and has board members from diverse disciplinary backgrounds, including social scientists, social activists, people living with HIV, and general medicine physicians (YRG Center for AIDS Research and Education, 2007). Following this meeting, staff at YRG CARE conducted an in-depth assessment among members of similar communities in different parts of Chennai to understand this issue in more detail and plan appropriate interventions. Specifically, communities classified as registered slums were selected in collaboration with the state government body, the Tamil Nadu Slum Clearance Board (TNSCB). These areas fulfilled the following criteria: horizontal slums with an average of greater than 1,500 people (approximately 400 to 1,200 households) and prior evidence of alcohol use, injection drug use, community-based sex work, or activity of men who have sex with men in the community. Enumeration and mapping of these communities had been done earlier either by the TNSCB or in preparation for the popular opinion leader intervention trial.

The design and implementation of this study largely follows the ethical principles for domestic violence research outlined by the WHO (World Health Organization, 2001). Specifically, the study methods are designed to minimize under-reporting of violence; data was managed in a way that protects the confidentiality of study subjects; and all field workers received specialized training prior to study implementation.

The survey was performed from June to September 2004 using a structured, interviewer-administered questionnaire by ten uniformly trained interviewers. Verbal informed consent was collected from all interviewees, and ten rupees (USD 0.25) were provided to each participant as compensation for their time. No locator or participant identifier information was collected in the questionnaire. Interviews were predominantly performed by interviewers of the same gender as the study subjects (approximately 70%); all interviewers were not of the same gender as study subjects due to resource limitations. The number of houses surveyed in a given slum was determined based on the estimated size of each community. The survey was performed house-to-house, and these houses were randomly selected and evenly distributed throughout a given slum based on the system of rows or streets that is the standard organizational structure of most slums. Of all women approached, 80% agreed to respond to the survey. A total of 1,136 males and 1,993 females completed the questionnaire. Nineteen women were excluded from analysis due to multiple missing data points; hence, data from 1,974 women were included in the final analysis.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the demographics of the populations and for frequencies of various types of violence experienced by women. All but one woman in this analysis were married and hence their intimate partners are their husbands. “Verbal abuse” was defined as yelling, shouting, or name-calling by one’s intimate partner. “Physical abuse” was defined as slapping, hitting, pushing, strangling, holding down, or kicking by one’s intimate partner. “Forced sex” was defined as being forced by one’s partner to have sex against one’s will. “Hurting with an object” was defined as suffering harm by any object, such as knife-stabbing or cigarette burns inflicted upon them by their intimate partner. A “joint family” was defined as a living situation in which the wife lives with her husband’s parents or other family members, in addition to her husband.

A case-control analysis was performed to compare the demographics and other factors between women who had experienced physical abuse five or fewer times in the last three months versus those who had experienced physical abuse more than five times in the same time period. A second case-control analysis was performed in a similar manner to compare women who had experienced forced sex more than five times in the last three months to those who had experienced it five or fewer times in the same time frame. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression were performed to identify factors associated with a history of domestic violence. All variables with a p-value less than 0.1 and variables of interest (even if not significant) in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. Various models were fit and the most parsimonious model has been reported in this analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using Intercooled STATA version 8.2 for Windows (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Prevalence Of Different Forms Of Violence

Of the 1,974 women who completed the survey, 99.4% and 74.9%, respectively, had ever experienced physical abuse or forced sex against their will at the hands of their male intimate partners (see Table 1). Twenty-five percent had also been hurt with an object by their husbands sometime in their lifetime, while 50% had witnessed threats or violence against family members. Rates of violence in the year preceding the survey were as follows: physical abuse and forced sex were the same as the lifetime prevalence, while 21.2% had been hurt with an object and 47% had threats or violence against their family in this time period.

Table 1.

Lifetime prevalence of various forms of violence against women or their family members perpetrated by their male partners (n=1974)

| Yes | No | Don’t know | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal abuse | 1948 (98.7) | 26 (1.32) | |

| Physical abuse | 1963 (99.44) | 11 (0.6) | |

| Forced sex | 1478 (74.9) | 491 (24.9) | 4 (0.2) |

| Hurting with an object | 491 (24.9) | 1477 (74.8) | 6 (0.3) |

| Threatened or attacked family members | 985 (49.9) | 984 (49.9) | 5 (0.3) |

Women were also asked about forms of violence they had experienced in the three months prior to the survey (Table 2). Almost all women (95.1%) were verbally abused more than five times in the previous three months, while 65.3% experienced episodes of physical abuse more than five times in that time period. Forty-five percent experienced forced sex more than five times in that time period.

Table 2.

Frequency of various forms of violence against women or their family members perpetrated by their male partners in the three months prior to the survey (n=1974)

| =>5 times | <5 times | One time | Not at all | Don’t know | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal abuse | 1878 (95.1) | 63 (3.2) | 3 (0.2) | 30 (1.5) | 0 |

| Physical abuse | 1288 (65.3) | 478 (24.2) | 173 (8.8) | 35 (1.8) | 0 |

| Forced sex | 881 (44.6) | 435 (22.0) | 132 (6.7) | 526 (26.7) | 0 |

| Hurting with an object | 163 (8.3) | 96 (4.9) | 111 (5.6) | 1602 (81.2) | 2 (0.1) |

| Threatened or attacked family members | 476 (24.1) | 168 (8.5) | 135 (6.9) | 1193 (60.5) | 0 |

Detailed questions were also asked about the nature of the episodes of forced sex. Of the entire cohort, 70.5% had succumbed to forced sex due to use of physical force, 68.1% due to verbal threats, and 26.2% due to insults prior to sex. Sixty percent had been treated with greater kindness before or after episodes of forced sex, and 24.8% had been forced to perform specific sexual acts that they would not normally perform.

Precipitating Factors And Risk Factors For Violence

Women were asked their opinions regarding the likelihood various factors would precipitate violence (Table 3). The top reason, drunkenness on the part of the man, was rated by 95.7% of women as “likely” to make a man violent. This was followed by disagreements about money (93.4%). Nine other factors were agreed upon as “likely” to precipitate violence by the majority of the respondents, including arguments over male affairs (88.1%), barrenness on the part of the woman (80.1%), a woman’s refusal to have sex (78.5%), dowry (75.8%), and a woman’s initiation of condom use (55.7%), among others.

Table 3.

Women’s Opinions of the Likelihood that Various Factors will make a Man Violent Towards his Wife or Intimate Partner (n=1974)

| Likely | Possible | Unlikely | No | No response | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disagreements about money | 1842 (93.4) | 106 (5.4) | 21 (1.1) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) |

| Arguments over male affairs | 1739 (88.1) | 233 (11.8) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.05) |

| Man’s criticism of woman’s household work | 1196 (60.4) | 711 (35.9) | 71 (3.5) | 0 | 5 (0.2) |

| Women’s desire for greater freedom (i.e., work or venturing in the community) | 996 (50.5) | 870 (44.1) | 93 (4.7) | 0 | 14 (0.7) |

| Disagreements involving relatives | 1067 (54.1) | 793 (40.2) | 96 (4.9) | 7 (0.4) | 11 (0.6) |

| Disagreements involving children | 952 (48.3) | 638 (32.3) | 250 (12.7) | 104 (5.3) | 29 (1.5) |

| Man is drunk | 1889 (95.7) | 79 (4.0) | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.05) | 1 (0.05) |

| Woman’s refusal of sex | 1548 (78.5) | 368 (18.7) | 17 (0.9) | 7 (0.4) | 33 (1.7) |

| Woman initiating condom use | 1099 (55.7) | 211 (10.69) | 105 (5.32) | 76 (3.85) | 482 (24.4) |

| Woman talking back to husband/elders | 881 (44.6) | 1055 (53.4) | 24 (1.2) | 11 (0.6) | 3 (0.2) |

| Man’s work-related tensions | 939 (47.6) | 873 (44.2) | 142 (7.2) | 7 (0.4) | 13 (0.7) |

| Man is tired | 1030 (52.2) | 734 (37.2) | 186 (9.4) | 9 (0.5) | 15 (0.8) |

| Dowry | 1495 (75.8) | 440 (22.3) | 16 (0.8) | 9 (0.5) | 13 (0.7) |

| Barren woman | 1582 (80.1) | 377 (19.1) | 4 (0.2) | 6 (0.3) | 5 (0.3) |

| Only girl child | 957 (48.5) | 818 (41.4) | 162 (8.21) | 18 (0.9) | 19 (1.0) |

| No particular reason | 892 (45.2) | 602 (30.5) | 238 (12.1) | 152 (7.7) | 90 (4.6) |

Factors associated with frequent physical abuse (more than five episodes in the prior three months) are presented in Table 4. In the univariate analysis, women of older age (greater than 43 years), living in joint families, living in rented homes, and living in homes without bathrooms demonstrated an increased likelihood of experiencing physical abuse. Women with a medium level of education (i.e., elementary or middle school) were also more likely to report physical abuse. Spouse’s educational level was strongly associated with inter-partner violence: women whose male partners had elementary and middle school educations had an odds of 1.7 and 1.99, respectively, for experiencing higher rates of violence. Protective factors against violence in univariate analysis were Christian religion, an income of greater than INR 2000 per month, and having two or more rooms in the house. Among women living in joint families, those who had four or more of their spouses’ family members living with them were 6.25 times less likely to experience a higher rate of violence.

Table 4.

Factors associated with frequency of physical abuse in univariate and multivariate logistic regression (n=1974)

| Demographic Characteristics | Frequency of Physical Abuse | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Regression Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| <=5 times in the last 3 months (n=686) | >5 times in the last 3 months (n=1288) | Odds ratio | p-value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI (LL, UL) | |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–25 | 212 (30.9) | 361 (28.0) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| 26–35a | 316 (46.1) | 596 (46.3) | 1.11 | 0.357 | 1.32 | (1.04–1.68) |

| 35–42 | 123 (17.9) | 235 (18.3) | 1.12 | 0.414 | 1.35 | (0.99–1.83) |

| 43 and oldera | 35 (5.1) | 96 (7.5) | 1.61 | 0.03 | 2.29 | (1.44–3.63) |

| Religion | ||||||

| Hindu | 555 (81) | 1104 (86) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Muslim | 12 (2) | 32 (3) | 1.34 | 0.392 | 1.22 | (0.61–2.46) |

| Christiana | 118 (17.2) | 151 (12) | 0.64 | <0.001 | 0.63 | (0.48–0.84) |

| Married for | ||||||

| 0–10 years | 312 (45.6) | 554 (43.1) | 1.0 | |||

| >= 11 years | 373 (54.5) | 733 (57.0) | 1.10 | 0.287 | ||

| Number of children | ||||||

| 0–2 | 391 (57.3) | 731 (56.9) | 1.0 | |||

| >=3 | 291 (42.7) | 553 (43.1) | 1.02 | 0.865 | ||

| Type of family | ||||||

| Nuclear | 602 (88) | 1079 (84) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Jointa | 83 (12) | 209 (15) | 1.4 | 0.015 | 1.94 | (1.42–2.64) |

| Number of spouse’s family members in house (only for those with a joint family)b | ||||||

| 1–3 | 3 (4) | 40 (19) | 1.0 | |||

| 4+ | 80 (96) | 169 (81) | 0.16 | <0.001 | ||

| Family Income | ||||||

| INR 1001–2000 | 595 (87) | 1171 (91.1) | 1 | |||

| INR >2000 | 89 (13) | 114 (8.9) | 0.66 | 0.004 | ||

| Woman’s education level | ||||||

| Illiterate | 264 (38.5) | 407 (31.6) | 1 | 1.0 | ||

| Elementarya | 160 (23.3) | 391 (30.4) | 1.59 | <0.001 | 1.42 | (1.10–1.84) |

| Middle Schoola | 184 (26.8) | 376 (29.2) | 1.33 | 0.019 | 1.31 | (1.01–1.7) |

|

| ||||||

| Higher Secondary or Graduate | 78 (11.4) | 114 (8.9) | 0.95 | 0.749 | 1.10 | (0.76–1.58) |

| Spouse’s education level | ||||||

| Illiterate | 214 (31.3) | 294 (22.8) | 1 | 1.0 | ||

| Elementarya | 148 (21.6) | 346 (26.9) | 1.70 | <0.001 | 1.61 | (1.22–2.12) |

| Middle Schoola | 168 (24.6) | 459 (35.6) | 1.99 | <0.001 | 1.91 | (1.46–2.49) |

| Higher Secondary and Graduate | 154 (22.5) | 189 (14.7) | 0.89 | 0.423 | 0.91 | (0.67–1.23) |

| Residence | ||||||

| Owned | 468 (68.2) | 787 (61.1) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Renteda | 218 (31.8) | 501 (38.9) | 1.37 | 0.002 | 1.57 | (1.26–1.95) |

| Number of rooms in home | ||||||

| 1 | 586 (85.4) | 1235 (95.9) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| 2 or morea | 100 (14.6) | 53 (4.1) | 0.25 | <0.001 | 0.24 | (0.17–0.35) |

| Bathroom in house shared with people outside the family | ||||||

| Yes | 130 (19.01) | 131 (10.2) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Noa | 554 (81) | 1150 (89.8) | 2.1 | <0.001 | 2.27 | (1.71–3.00) |

| How do you rate your family life?b | ||||||

| Very cordial | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Cordial | 7 (1.02) | 6 (0.47) | 1 | --- | --- | |

| Somewhat cordial | 552 (80.5) | 826 (64.2) | 1.75 | 0.319 | --- | --- |

| Unhappy | 102 (14.9) | 293 (22.8) | 3.35 | 0.033 | --- | --- |

| Miserable | 13 (1.9) | 37 (2.9) | 3.32 | 0.062 | --- | --- |

| Violent | 12 (1.75) | 125 (9.71) | 12.2 | <0.001 | --- | --- |

Statistically significant associations after multivariate logistic regression analysis

Not included in multivariate regression analysis

In the multivariate analysis, all significant associations in the univariate analysis except income retained their significance in the multivariate model (Table 4). Of note, all women older than 25 years of age had an increased risk of physical abuse on multivariate analysis. Women older than 42 years of age had an odds ratio of 2.29 for experiencing physical violence more than five times in the three months prior to the survey.

Women living in joint families were more likely to be subject to frequent physical abuse, while those in homes without bathrooms had an elevated odds of 2.27. Having a spouse with a medium level of education remained strongly associated with violence (odds ratios of 1.61 and 1.91, respectively), while a medium level education on the part of the woman was also associated with elevated violence, though to a lesser extent. Living in a home with two or more rooms was associated with a 4.2 times decreased likelihood of extreme physical abuse.

Results of univariate and multivariate analyses examining risk factors for frequent forced sex (greater than five times in the last three months) are reported in Table 5. In the univariate analysis, elementary or middle school education on the part of the woman or her male partner, a rented house, and not having a bathroom in the house were all positively associated with frequent forced sex, while having two or more rooms in the house significantly decreased the odds. Similar to the situation of frequent physical abuse, of women living in joint families, those with four or more of the spouse’s family member’s living in the household had a decreased likelihood of frequent forced sex.

Table 5.

Factors associated with frequency of forced sex in univariate and multivariate logistic regression (n=1974)

| Demographic Characteristics | Frequency of Forced Sex | Univariate Regression | Multivariate Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| <=5 times in the last 3 months (n=1093) | >5 times in the last 3 months (n=881) | Odds ratio | p-value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI (LL, UL) | |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–25 | 312 (28.6) | 261 (29.6) | 1.0 | |||

| 26–35 | 508 (46.5) | 404 (45.9) | 0.95 | 0.64 | ||

| 35–42 | 202 (18.5) | 156 (17.7) | 0.92 | 0.56 | ||

| 43 and older | 71 (6.5) | 60 (6.8) | 1.01 | 0.96 | ||

| Religion | ||||||

| Hindu | 917 (84) | 742 (84.3) | 1.0 | |||

| Muslim | 22 (2.01) | 22 (2.5) | 1.2 | 0.49 | ||

| Christian | 153 (14.01) | 116 (13.2) | 0.9 | 0.62 | ||

| Married for | ||||||

| 0–10 years | 482 (44.1) | 384 (43.7) | 1.0 | |||

| >= 11 years | 611 (55.9) | 495 (56.3) | 1.0 | 0.98 | ||

| Number of children | ||||||

| 0–2 | 633 (58.0) | 489 (55.9) | 1.0 | |||

| >=3 | 458 (42.0) | 386 (44.1) | 1.09 | 0.34 | ||

| Type of family | ||||||

| Nuclear | 931 (85.3) | 750 (85.3) | 1.0 | |||

| Joint | 161 (14.7) | 131 (14.8) | 1.0 | 0.94 | ||

| Number of spouse’s family members in house (only for those with a joint family)b | ||||||

| 1–3 | 10 (6.21) | 33 (25.2) | 1.0 | |||

| 4+ | 151 (93.79) | 98 (74.8) | 0.2 | <0.001 | ||

| Family Income | ||||||

| INR 1001–2000 | 966 (88.7) | 800 (90.9) | 1.0 | |||

| INR >2000 | 123 (11.3) | 80 (9.1) | 0.79 | 0.110 | ||

| Woman’s education level | ||||||

| Illiterate | 407 (37.2) | 264 (30) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Elementarya | 265 (24.3) | 286 (32.5) | 1.66 | <0.001 | 1.46 | (1.15–1.86) |

| Middle Schoola | 296 (27.1) | 264 (30) | 1.38 | 0.006 | 1.32 | (1.04–1.68) |

| Higher Secondary or Graduate | 125 (11.4) | 67 (7.6) | 0.87 | 0.264 | 0.88 | (0.62–1.25) |

| Spouse’s education level | ||||||

| Illiterate | 321 (29.4) | 187 (21.2) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Elementarya | 228 (20.9) | 266 (30.2) | 2.0 | <0.001 | 1.86 | (1.43–2.41) |

| Middle Schoola | 324 (29.7) | 303 (34.4) | 1.61 | <0.001 | 1.53 | (1.19–1.97) |

| Higher Secondary or Graduate | 218 (20.0) | 125 (14.2) | 0.98 | 0.913 | 1.01 | (0.74–1.36) |

| Residence | ||||||

| Owned | 736 (67.3) | 519 (58.9) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Renteda | 357 (32.6) | 362 (41.1) | 1.44 | <0.001 | 1.43 | (1.18–1.74) |

| Number of rooms in home | ||||||

| 1 | 966 (88.4) | 855 (97.1) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| 2 or morea | 127 (11.6) | 26 (3.0) | 0.23 | <0.001 | 0.26 | (0.17–0.40) |

| Bathroom in house shared with people outside the family | ||||||

| Yes | 174 (15.9) | 87 (9.9) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Noa | 916 (84.04) | 788 (90.1) | 1.72 | <0.001 | 1.87 | (1.4–2.49) |

| How do you rate family life?b | ||||||

| Very cordial | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Cordial | 12 (1.1) | 1 (0.11) | 1 | --- | --- | |

| Somewhat cordial | 791 (72.4) | 587 (66.7) | 8.91 | 0.04 | --- | --- |

| Unhappy | 219 (20.0) | 176 (20.0) | 9.64 | 0.03 | --- | --- |

| Miserable | 21 (1.9) | 29 (3.3) | 16.57 | 0.009 | --- | --- |

| Violent | 50 (4.6) | 87 (9.9) | 20.88 | 0.004 | --- | --- |

Statistically significant associations after multivariate regression analysis

Not included in multivariate regression analysis

In the multivariate analysis, all of these associations remained significant. Of note, having two or more rooms in one’s home decreased the odds of frequent forced sex by 3.85 times, while not having a bathroom in the house increased the odds of frequent forced sex 1.87 times. A woman whose spouse has an elementary school education had a 1.86 times increased odds of frequent forced sex compared to women with illiterate spouses.

Attitudes Of Women Toward Violence

Women were asked whether they considered the following acts to be “violence”: verbal abuse (yelling, shouting, and name-calling), suspicion, threats to cause injury, slapping, hitting, kicking, pushing/pulling, dragging or holding a person down, burning, strangling, attacking with a weapon, and forcing sex upon another person. All of these acts were considered by greater than 85% of women to constitute “violence.”

Tables 4 and 5 also contain data regarding women’s views of their family life stratified by frequency of physical abuse or forced sex. Of women who experienced less frequent physical abuse (less than five times in the prior three months), 80.5% rated their family life as “somewhat cordial,” while less than 2% rated it as “violent.” By contrast, 64.2% of women who experienced physical abuse greater than five times in the prior three months rated their family life as “somewhat cordial,” while almost 10% rated it as “violent.” When examining women who experienced different frequencies of forced sex, a similar trend was observed (Table5).

DISCUSSION

The most striking finding in this study is the extremely high prevalence of all forms of domestic violence in these communities of the urban poor in south India. The 99.4% lifetime prevalence of physical abuse in this study is higher than in prior reports from south India (with rates ranging from 22–43%) (Jejeebhoy, 1998; Jeyaseelan et al., 2004; Rao, 1997) and, indeed, than in previous studies from all of South Asia (with rates ranging from 24–75%) (Bates et al., 2004; Jejeebhoy, 1998; Jeyaseelan et al., 2004; Koenig et al., 2006; Mahajan, 1990; Martin et al., 1999; Martin et al., 2002). These rates also exceed reports of physical violence in recent studies from Africa and the Middle East (13–50%) (Blanc et al., 1996; Deyessa et al., 1998; Diop-Sidibe et al., 2006; Dunkle et al., 2004b; Heise et al., 1999; Jeyaseelan et al., 2004; Maman et al., 2002), Latin America (10–69%) (Heise et al., 1999; Jeyaseelan et al., 2004), other Asian countries (10–67%) (Heise et al., 1999; Jeyaseelan et al., 2004), Europe (14–58%) (Heise et al., 1999), and North America (22–29%) (Rodgers, 1994; Tjaden & Thoennes, 1998). Even the rate of physical abuse experienced by women in the three months prior to the survey is higher than the lifetime prevalence of violence in most Indian and international reports. Similarly, the lifetime prevalence of women who had been forced to have sex against their will by their partners is higher than in recent Indian studies (26–32%) (Koenig et al., 2006; Martin et al., 1999; Waldner et al., 1999), as well as those from other developing countries (15–54%) (Abrahams et al., 2004; Dunkle et al., 2004b; Koenig et al., 2004; Maman et al., 2002; Smith-Fawzi et al., 2005).

The near universal response that a man’s drunkenness is a major precipitating factor for violence is consistent with many other studies implicating alcohol use as a, if not the, major factor leading to domestic violence (Jejeebhoy, 1998; Jewkes et al., 2001; Koenig et al., 2003; Koenig et al., 2004; Rao, 1997). Two other precipitating factors rated by a large proportion of women as likely to make a man violent—childlessness and arguments over dowry—are also prominent in other studies from India, reflecting the role of specific cultural norms in instigating violence (Jejeebhoy, 1998; Koenig et al., 2006; Rao, 1997). Dowry is the transfer of money or gifts from the wife’s to the husband’s family at the time of marriage, and it may be come a source of conflict in the marriage when the husband or his family perceives this sum to have been inadequate (Rao, 1997).

Several interrelated findings in this survey highlight the vulnerability of women in these communities to HIV and other STIs: the high prevalence of forced sex, the view of many women that refusal of sex and attempts to initiate condom use are likely to instigate violence, and the high rate of women indulging their husbands in sex to avoid physical assault. Studies from south India (Go et al., 2003), Brazil (Goldstein, 1994), South Africa (Karim, 2001), and the US (Wingood & DiClemente, 1997) similarly highlight the difficulties of negotiating condom use among abused women. Married women specifically are more likely to face violence when requesting that husbands use condoms, as it is often seen as an admission of marital infidelity (Go et al., 2003; Pallikadavath & Stones, 2003). Moreover, the high rate of female sterilization for contraception among married couples in India may further limit the ability to negotiate condom use for disease prevention (International Institute for Population Sciences & ORC Macro, 2000; Pallikadavath & Stones, 2003). Indeed, married women in India have been shown to have very low rates of condom use (3%) (International Institute for Population Sciences & ORC Macro, 2000). Such data highlight weaknesses in prevailing HIV prevention strategies focusing primarily on monogamy and condom use in the absence of social interventions to reduce domestic violence.

Due to the extremely high prevalence of violence in these communities, in the case-control analyses, we had to use as the control group women who had experienced relatively less frequent violence (i.e., physical abuse or forced sex less than five times in the last three months) rather than women who had never experienced violence, as the latter experience was rarely encountered. This makes the results of these analyses difficult to compare with other such studies (Jejeebhoy, 1998; Koenig et al., 2006; Smith-Fawzi et al., 2005). Nevertheless, factors associated with high levels of both physical abuse and forced sex emerge from the multivariate regression analyses.

Of these factors, the effects of the educational status of both partners and household status are of particular interest. While some studies suggest that higher levels of education among women are protective against domestic violence (Jejeebhoy & Cook, 1997), other studies from India report counterintuitive findings (similar to our data) that some levels of education confer little protection or actually increase the likelihood of violence. One study from rural Uttar Pradesh found a decreased risk of physical abuse with greater than seven years of education among both husbands and wives; however, this same level of education among husbands actually increased the risk of sexual violence (Koenig et al., 2006). Jejeebhoy and colleagues found that both primary and secondary education on the part of women were protective against physical abuse in Tamil Nadu, while in Uttar Pradesh, primary education alone offered no protection to women (Jejeebhoy, 1998). This same study also found that women whose educational levels exceeded that of their husbands experienced less violence, a trend not observed in our analysis. Our data, as well as the conflicting results from these prior epidemiological studies, suggest that the complex relationship between education and domestic violence may require more nuanced ethnographic and qualitative studies for better clarification.

Some of the strongest associations in our analyses were seen with indicators of household economic status: owning one’s home, having more than one room in the house, and having a bathroom in the house shared with outsiders (in communities where most people cannot afford to have bathrooms in their homes) all conferred strong protection against both physical abuse and forced sex. Since 90% of families fell into the lowest income group recorded in this survey (INR 1001–2000), it was not possible to effectively control for income in the multivariate analysis. Therefore, these indicators of household status may actually be surrogate markers for differences in income, and the protective effects conferred by these indicators may be due to greater economic security. Greater economic security may decrease the incidence of violence by reducing the daily stress faced by families and increasing the autonomy of women. Many other studies similarly report that economic security in the form of higher incomes and greater household assets is protective against physical or sexual violence (Coker & Richter, 1998; Jejeebhoy, 1998; Koenig et al., 2006; Nagy et al., 1994; Smith-Fawzi et al., 2005).

The higher violence associated with a joint family (in which the woman lives with members of her husband’s family) may be due to the role of the mother-in-law. In south India, mothers-in-law often retain control of the household and place pressure for greater dowry from the woman’s family, putting them at odds with their daughters-in-law (Rao, 1997; Panchanadeswaran & Koverola, 2005).

The above data highlight factors that increase the likelihood of violence for some women within these communities, but they do not explain why these communities in Chennai in particular have the highest burden of domestic violence recorded in India and, perhaps, internationally. Since previous studies from India have focused on rural areas (Jejeebhoy, 1998; Jejeebhoy & Cook, 1997; Koenig et al., 2006; Martin et al., 1999; Martin et al., 2002; Rao, 1997) and non-slum dwelling urban populations (Jeyaseelan et al., 2004), much of the increased violence in this study may be attributable to the particular socioeconomic circumstances of the urban poor in south India. In addition to poverty, slum dwellers face multiple forms of marginalization and social deprivation, including high population density, risk of property loss due to housing demolitions and natural disasters, and poor or non-existent access to potable water, electricity, and sanitation (with its associated high burden of infectious diseases). They are often forced to occupy locations in the city such as trash dumps, spaces next to sewer ditches and rivers, and areas immediately adjacent to railroad tracks. While we can only speculate on reasons for the high domestic violence rates in these communities, these multiple forms of “structural violence” faced by the urban poor are likely to contribute to this problem.

Moreover, our data suggest that the pervasiveness of violence in these communities leads to its tolerance as normative behavior. For instance, 64.2% of women who experienced the most extreme rates of violence (i.e., physical abuse more than five times in the last three months) still rated their family life as “somewhat cordial,” while only 12.6% rated their family life as “miserable” or “violent.” Other studies also report findings suggesting that domestic violence is at least partially accepted as “normal” behavior (Karim, 2001; Go et al., 2003; Jejeebhoy, 1998; Maman et al., 2002; Rao, 1997). Jejeebhoy found that 93% of women from a sample in rural Tamil Nadu believe that a man might be justified in beating his wife in certain circumstances (such as neglect of household duties, disobedience, or use of alcohol), and only 6% believed that a woman is justified in leaving her husband if he beats her frequently (Jejeebhoy, 1998). In a study of south Indian villages, Rao observed that while communities could occasionally intervene to stop wife-beating, there was generally a high tolerance for such behavior that usually prevented intervention (Rao, 1997). In one South African study, nearly half of women did not believe that they had the right to refuse sex with their partners or insist on condom use, while 62% thought their partner had a right to multiple partners (Karim, 2001).

In light of these findings, education focused on transforming social attitudes and beliefs surrounding domestic violence may be an important means of intervention, so that such behavior is no longer considered normative. Community mobilization to create safe spaces for women and for collective action against domestic violence may reduce its prevalence. Increasing access to substance abuse programs should be a crucial component of these interventions, as alcohol use is almost universally implicated as a major factor precipitating violence. Such programs at both the community level and in clinical settings may be crucial for HIV/AIDS prevention, especially in India, where most infected women are married and monogamous (Newmann et al., 2000). Evidence suggests such interventions can produce behavior change: a Rwandan study found that an intensive, male-focused counseling program reduced rates of coercive sex and dramatically increased condom use among serodiscordant couples (Roth et al., 2001). At the same time, preventing the spread of HIV/AIDS and other STIs among women cannot rely on behavior change alone: the development of effective vaginal microbicides and greater distribution of female condoms may be critical strategies to help women covertly protect themselves from infection, since most cannot negotiate condom use due to the threat of violence.

Addressing domestic violence also requires changes at the institutional and legal levels, following a human rights-based approach (Jewkes, 2002; United Nations General Assembly, 1993; United Nations, 1995). While the Indian government is obliged both by its Constitution and its affirmation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women to take effective steps to eliminate violence against women, the government has had little accountability for the massive gap between legal clauses and the reality of pervasive domestic violence (Bhattacharya, 2004; Jejeebhoy & Cook, 1997). Important steps that could be taken at the public policy level include reforming public institutions (for example, by making policemen more receptive to the needs of victimized women (Bhattacharya, 2004)) and enforcing existing legislation (for instance, laws restricting dowry practices).

The major limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, which limits the ability to infer a causal relationship between domestic violence and the associated factors. In addition, while the frequency of forced sex suggests that women in these communities may be at high risk of acquiring HIV and other STIs, additional behavioral and biological data that would have helped understand this association better were not collected.

Our data suggest a connection between socioeconomic factors and domestic violence. Therefore, structural interventions aimed at uplifting the overall socioeconomic situation of slum communities, and the economic situation of women in particular, may help mitigate violence in these communities. Indeed, in light of the extreme violence in these communities, perhaps the most important implication of this study is the urgent need for further research into the way the “structural violence” faced by the Indian urban poor (in the forms of poverty, social exclusion, lack of access to basic amenities, etc.) may manifest itself in high rates of sexual and physical violence against women.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Ford Foundation. Ramnath Subbaraman was supported by a Fogarty-Ellison Overseas Fellowship in Global Health and Clinical Research (grant # 3 D43 TW000237-13S1) and by a Yale University School of Medicine short-term research fellowship. Sunil Solomon was supported, in part, by a grant from the Fogarty International Center/USNIH (grant # 2 D 43 TW000010-19-AITRP). The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the data entry team and the field staff, who conducted all the interviews, for their efforts. We would also like to thank the participants for volunteering their time to respond to the questionnaire.

References

- Abrahams N, Jewkes R, Hoffman M, Laubsher R. Sexual violence against intimate partners in Cape Town: Prevalence and risk factors reported by men. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2004;82:330–337. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates LM, Schuler SR, Islam F, Islam K. Socioeconomic factors and processes associated with domestic violence in rural Bangladesh. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2004;30:190–199. doi: 10.1363/3019004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya R, editor. Behind closed doors: Domestic violence in India. New Delhi: Sage Publications, India; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Blanc AK, Wolff B, Gage AJ, Ezeh A, Neema S, Ssekamatte-Ssebuliba J. Negotiating reproductive outcomes in Uganda. Calverton, MD: Macro International; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bollinger RC, Tripathy SP, Quinn TC. The human immunodeficiency virus epidemic in India. Current magnitude and future projections. Medicine: Analytical Reviews of General Medicine, Neurology, Psychiatry, Dermatology, and Pediatries. 1995;74:97–106. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199503000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359:1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC, Woods AB, Chouaf KL, Parker B. Reproductive health consequences of intimate partner violence. A nursing research review. Clinical Nursing Research. 2000;9:217–237. doi: 10.1177/10547730022158555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Richter DL. Violence against women in Sierra Leone: Frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence and forced sexual intercourse. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 1998;2:61–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyessa N, Kassaye M, Demeke B, Taffa N. Magnitude, type and outcomes of physical violence against married women in Butajira, southern Ethiopia. Ethiopian Medical Journal. 1998;36:83–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diop-Sidibe N, Campbell JC, Becker S. Domestic violence against women in Egypt--Wife beating and health outcomes. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62:1260–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, Gray GE, McIntryre JA, Harlow SD. Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Lancet. 2004a;363:1415–1421. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, Yoshihama M, Gray GE, McIntyre JA, Harlow SD. Prevalence and patterns of gender-based violence and revictimization among women attending antenatal clinics in Soweto, South Africa. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004b;160:230–239. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer PE, Connors M, Simmons J, editors. Women, poverty, and AIDS: Sex, drugs, and structural violence. Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gangakhedkar RR, Bentley ME, Divekar AD, Gadkari D, Mehendale SM, Shepherd ME, et al. Spread of HIV infection in married monogamous women in India. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278:2090–2092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go VF, Sethulakshmi CJ, Bentley ME, Sivaram S, Srikrishnan AK, Solomon S, et al. When HIV-prevention messages and gender norms clash: The impact of domestic violence on women’s HIV risk in slums of Chennai, India. AIDS and Behavior. 2003;7:263–272. doi: 10.1023/a:1025443719490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DM. AIDS and women in Brazil: The emerging problem. Social Science and Medicine. 1994;39:919–929. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Tamil Nadu. Tamil Nadu human development report 2003. Chennai: Social Science Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottemoeller M. Ending violence against women. Population Reports Series L: Issues in World Health. 1999;11:1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heise L, Pitanguy J, Germain A. Violence against women: The hidden health burden. Washington, D.C: World Bank; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences, & ORC Macro. National family health survey, India, 1998–1999. Mumbai: IIPS; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin KL, Edlin BR, Wong L, Faruque S, McCoy HV, Word C, et al. Urban rape survivors: Characteristics and prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus and other sexually transmitted infections. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;85:330–336. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00425-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jejeebhoy SJ. Wife beating in rural India: A husband’s right? Evidence from survey data. Economic and Political Weekly. 1998;33:855–862. [Google Scholar]

- Jejeebhoy SJ, Cook RJ. State accountability for wife-beating: The Indian challenge. Lancet. 1997;349(Suppl 1):sI10–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)90004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R. Preventing sexual violence: A rights-based approach. Lancet. 2002;360:1092–1093. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Penn-Kekana L, Levin J, Ratsaka M, Schrieber M. Prevalence of emotional, physical and sexual abuse of women in three South African provinces. South African Medical Journal. 2001;91:421–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyaseelan L, Sadowski LS, Kumar S, Hassan F, Ramiro L, Vizcarra B. World studies of abuse in the family environment--risk factors for physical intimate partner violence. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion. 2004;11:117–124. doi: 10.1080/15660970412331292342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim QA. Barriers to preventing human immunodeficiency virus in women: Experiences from KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association. 2001;56:193–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney JW, Reinholtz C, Angelini PJ. Sexual abuse, sex before age 16, and high-risk behaviors of young females with sexually transmitted diseases. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing: JOGNN/NAACOG. 1998;27:54–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1998.tb02591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimerling R, Armistead L, Forehand R. Victimization experiences and HIV infection in women: Associations with serostatus, psychological symptoms, and health status. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1999;12:41–58. doi: 10.1023/A:1024790131267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig MA, Lutalo T, Zhao F, Nalugoda F, Kiwanuka N, Wabwire-Mangen F, et al. Coercive sex in rural Uganda: Prevalence and associated risk factors. Social Science and Medicine (1982) 2004;58(4):787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00244-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig MA, Lutalo T, Zhao F, Nalugoda F, Wabwire-Mangen F, Kiwanuka N, et al. Domestic violence in rural Uganda: Evidence from a community-based study. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2003;81:53–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig MA, Stephenson R, Ahmed S, Jejeebhoy SJ, Campbell J. Individual and contextual determinants of domestic violence in North India. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:132–138. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan A. Instigators of wife-battering. In: Sood S, editor. Violence against women. Jaipur, India: Arihant Publishers; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Maman S, Mbwambo JK, Hogan NM, Kilonzo GP, Campbell JC, Weiss E, et al. HIV-positive women report more lifetime partner violence: Findings from a voluntary counseling and testing clinic in Dar es salaam, Tanzania. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:1331–1337. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SL, Kilgallen B, Tsui AO, Maitra K, Singh KK, Kupper LL. Sexual behaviors and reproductive health outcomes: Associations with wife abuse in India. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:1967–1972. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.20.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SL, Moracco KE, Garro J, Tsui AO, Kupper LL, Chase JL, et al. Domestic violence across generations: Findings from northern India. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;31:560–572. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.3.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehendale SM, Shepherd ME, Divekar AD, Gangakhedkar RR, Kamble SS, Menon PA, et al. Evidence for high prevalence and rapid transmission of HIV among individuals attending STD clinics in Pune, India. The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 1996;104:327–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy S, Adcock AG, Nagy MC. A comparison of risky health behaviors of sexually active, sexually abused, and abstaining adolescents. Pediatrics. 1994;93:570–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS Control Organization of India. An Overview of the Spread and Prevalence of HIV/AIDS in India. 2006 Retrieved 6/14, 2006 from http://www.nacoonline.org/facts_overview.htm.

- Newmann S, Sarin P, Kumarasamy N, Amalraj E, Rogers M, Madhivanan P, et al. Marriage, monogamy and HIV: A profile of HIV-infected women in South India. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2000;11:250–253. doi: 10.1258/0956462001915796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group. Formative study conducted in five countries to adapt the community popular opinion leader intervention. AIDS. 2007;21(suppl 2):S91–98. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000266461.33891.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallikadavath S, Stones RW. Women’s reproductive health security and HIV/AIDS in India. Economic and Political Weekly. 2003;38:4173–4181. [Google Scholar]

- Panchanadeswaran S, Koverola C. The voices of battered women in India. Violence Against Women. 2005;11:736–758. doi: 10.1177/1077801205276088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda S, Chatterjee A, Bhattacharya SK, Manna B, Singh PN, Sarkar S, et al. Transmission of HIV from injecting drug users to their wives in India. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2000;11:468–473. doi: 10.1258/0956462001916137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao V. Wife-beating in rural South India: A qualitative and econometric analysis. Social Science and Medicine. 1997;44:1169–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers K. Wife assault: The findings of a national survey. Juristat. 1994;14:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues JJ, Mehendale SM, Shepherd ME, Divekar AD, Gangakhedkar RR, Quinn TC, et al. Risk factors for HIV infection in people attending clinics for sexually transmitted diseases in India. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed) 1995;311:283–286. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth DL, Stewart KE, Clay OJ, van Der Straten A, Karita E, Allen S. Sexual practices of HIV discordant and concordant couples in Rwanda: Effects of a testing and counselling programme for men. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2001;12:181–188. doi: 10.1258/0956462011916992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoes EA, Babu PG, John TJ, Nirmala S, Solomon S, Lakshminarayana CS, et al. Evidence for HTLV-III infection in prostitutes in Tamil Nadu (India) The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 1987;85:335–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Fawzi MC, Lambert W, Singler JM, Tanagho Y, Leandre F, Nevil P, et al. Factors associated with forced sex among women accessing health services in rural Haiti: Implications for the prevention of HIV infection and other sexually transmitted diseases. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;60:679–689. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamil Nadu Ministry of Home Affairs. Tamil Nadu census 2001. 2001 Retrieved 4/25, 2006 from http://www.census.tn.nic.in/

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Prevalence, incidence, and consequences of violence against women: Findings from the national violence against women survey. Washington, D.C: National Institute of Justice; 1998. No. 718-A-03. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Report of the fourth world conference on women. New York: United Nations; 1995. Document A/conf 177/20. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women. New York: United Nations; 1993. No. 48/104. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS, United Nations Population Fund, & United Nations Development Fund for Women. Women and HIV/AIDS: Confronting the crisis. 2004 Retrieved 03/15, 2006 from http://www.unfpa.org/hiv/women/docs/women_aids.pdf.

- van der Straten A, King R, Grinstead O, Serufilira A, Allen S. Couple communication, sexual coercion and HIV risk reduction in Kigali, Rwanda. AIDS. 1995;9:935–944. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199508000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldner LK, Vaden-Goad L, Sikka A. Sexual coercion in India: An exploratory analysis using demographic variables. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1999;28:523–538. doi: 10.1023/a:1018717216774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Rape among African American women: Sexual, psychological, and social correlates predisposing survivors to risk of STD/HIV. Journal of Women’s Health: The Official Publication of the Society for the Advancement of Women’s Health Research. 1998;7:77–84. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1998.7.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. The effects of an abusive primary partner on the condom use and sexual negotiation practices of African-American women. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:1016–1018. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Putting women first: ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women. 2001 (WHO/FCH/GWH/01.1). Retrieved 10/17, 2007 from http://www.who.int/gender/violence/womenfirtseng.pdf.

- Wyatt GE, Myers HF, Williams JK, Kitchen CR, Loeb T, Carmona JV, et al. Does a history of trauma contribute to HIV risk for women of color? Implications for prevention and policy. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:660–665. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YRG Center for AIDS Research and Education. Information on YRG CARE Review and Advisory Boards. 2007 Retrieved 10/17, 2007 from http://www.yrgcare.org/overview/boards.htm.