Abstract

Purpose

This research was conducted to compare the management and the outcome of patients with colovesical fistulae of different aetiologies.

Methods

Retrospective data were collected from 2002 to 2012 and analyzed with SPSS ver. 17. Age, gender, aetiology, management, hospital stay, postoperative complications, and mortality were studied and compared among colovesical fistulae of different aetiologies.

Results

A total of 55 patients, 46 males (84%) and 9 females (16%), with a median age of 65 years (interquartile range [IQR], 48-75 years) were studied. Diverticular disease was the most common benign cause and recto-sigmoid cancer the most common malignancy. Anterior resection and bladder repair were the most frequent operations in benign cases, as was total pelvic exenteration in the malignant group. Multiple intestinal loop involvement and subsequent resection were significantly higher in those with Crohn disease than it was in patients of colovesical fistula due to all other causes collectively (60% vs. 6%, P = 0.006). Patients with malignancy had a higher postoperative complication rate than patients who did not (12 [80%] vs. 7 [32%], P = 0.0005). Pelvic collection (11, 22%) was the most frequent early complication (predominantly in the malignant group) whereas incisional hernia (8, 22%) was the most common late complication, with a predominance in the benign group. The median hospital stay was significantly prolonged in the malignant group (32 days; IQR, 17-70 days vs. 16 days; IQR, 11-25 days; P < 0.001).

Conclusion

Despite their having similar clinical presentation, colovesical fistulae of various aetiologies differ significantly in management and outcome.

Keywords: Colovesical fistula, Fistula, Pelvic exenteration, Diverticulitis, Adenocarcinoma

INTRODUCTION

A colovesical fistula is a well-known complication of many different diseases. The first description of a colovesical fistula is attributed to Rufus of Ephesus in AD 200 [1], but it was not until 1888 that Cripps produced his classic monograph on the subject [2]. A large number of causes are described in the literature, of which the most common are diverticular disease, inflammatory bowel disease (predominantly Crohn disease) [3, 4], colorectal cancers, (predominantly recto-sigmoid cancers), and urological and gynecological cancers [5]. Rare causes are laparoscopic and open inguinal hernia repair [6, 7], foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract [8], other laparoscopic and open surgical procedures [9], benign gastrointestinal and urological diseases [10, 11], and various other conditions.

In research literature and surgical textbooks, a colovesical fistula is usually reported as a single pathology, which creates an impression of a single disease in the mind of the reader. A colovesical fistula can be a complication of many diseases, the aetiologies or pathogenesis of whom may be entirely different.

The objective of the study was to discuss the management and outcome of colovesical fistulae on the basis of aetiology.

METHODS

Data were collected retrospectively from electronic and paper records of patients admitted to a tertiary care hospital between 2003 and 2012 with a diagnosis of a colovesical fistula. The inclusion criteria were all patients admitted with a confirmed diagnosis of a colovesical fistula of any nature. Patients with incomplete record were excluded. Data on age, gender, symptoms, preoperative investigations, etiology, operative risk, preoperative therapy, surgical procedures, operative findings, postoperative complications, hospital stay, follow-up, and early and late mortality were collected.

The data were analyzed with SPSS ver. 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For comparison, the data were arranged into groups on the basis of similarities in pathology, management and outcome. The specific features of individual pathological conditions (if any) were discussed separately. Age, hospital stay and follow-up were reported in the form of medians (IQR) and compared between groups by using the Mann-Whitney U test (P < 0.05). Other variables were reported in the form of frequency and were compared between groups by using the chi square or the Fischer exact test (P < 0.05), as appropriate.

RESULTS

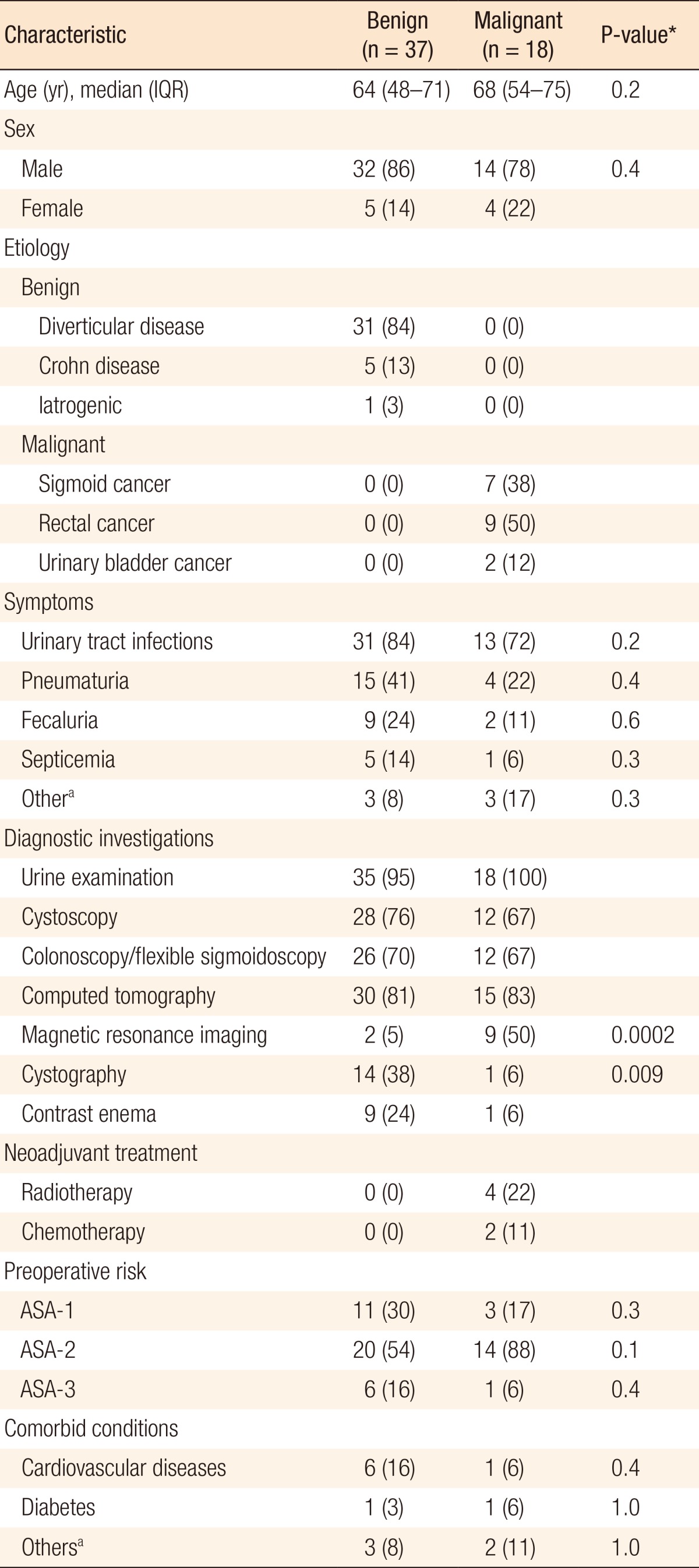

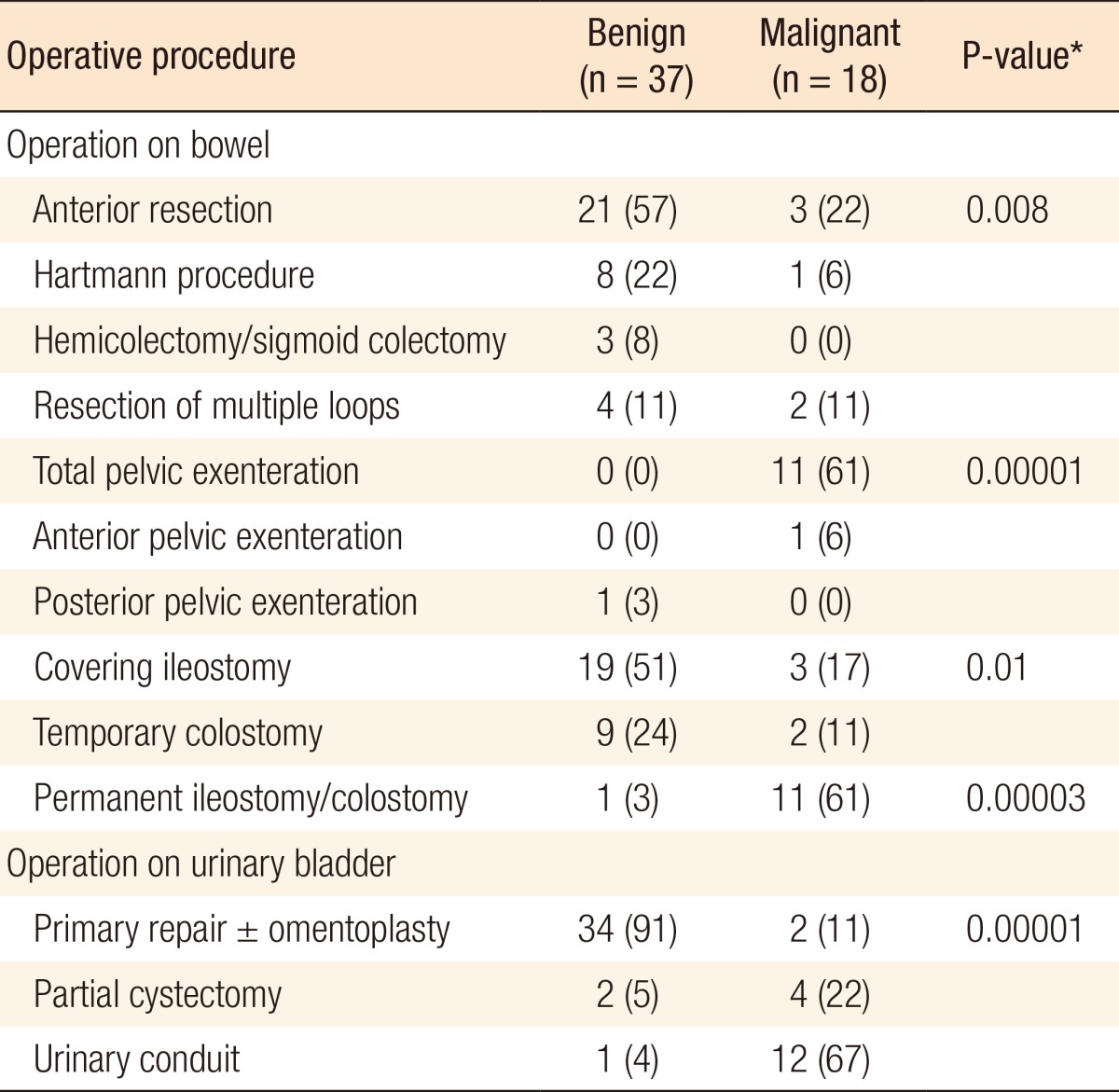

A total of 57 patients were admitted between 2003 and 2012 with a diagnosis of a colovesical fistula. Two patients were excluded due to incomplete records, and 55 patients were finally included in this study. The mean age of the 55 patients was 65 years (IQR, 48-75 years), with a male preponderance (46, 84%). For the sake of practicality, patients were divided in two major categories, benign and malignant colovesical fistulae, on the basis of similarities in pathology. The characteristics of patients in these groups are compared in Table 1. Comparisons of the sites of fistulae are given in Table 2, and comparisons of operative findings and procedures are given in Table 3. The outcomes for the patients in the benign and the malignant colovesical fistula groups are compared in Table 4. Some additional features of these groups and individual pathological conditions are discussed below.

Table 1. Characteristics of patients with benign and malignant colovesical fistulae.

Values are presented as number (%) unless otherwise indicated.

IQR, interquartile range; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologist.

aBleeding from rectum, hematuria, altered bowel habit, urine in stools.

*P < 0.05, statistically significance.

Table 2. Difference in involved sites between benign and malignant colovesical fistulae.

Values are presented as number (%).

aBenign colovesical fistula excluding Crohn disease; details of Crohn disease are in the text.

*P < 0.05, statistically significance.

Table 3. Operative findings and procedures in benign and malignant colovesical fistulae.

Values are presented as number (%).

*P < 0.05, statistically significance.

Table 4. Comparison of outcomes between benign and malignant colovesical fistulae.

Values are presented as number (%) unless otherwise indicated.

IQR, interquartile range.

aWound hematoma, lymphedema, jaundice.

*P < 0.05, statistically significance.

Benign colovesical fistula

A total of 37 patients had colovesical fistula due to benign causes, including 31 cases with diverticular disease, five cases with Crohn disease and one case with iatrogenic causes. Patients with Crohn disease had some unique characteristics; the terminal ileum and the proximal colon were involved more frequently (ileum [40%], caecum [20%], sigmoid [40%]) whereas the distal colon was involved more frequently in patients with other benign conditions (sigmoid [91%], rectum [9%]). Multiple intestinal loop involvement and subsequent resection were significantly higher in patients with Crohn disease than in patients without it (60% vs. 6%, P = 0.006).

Malignant colovesical fistula

A total of 18 patients had a colovesical fistula due to a malignant cause, which included sigmoid cancer (7), rectal cancer (9), and squamous cell cancer of the urinary bladder (2). A moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma (T4N0Mx) was the most common histo-pathological type in patients with recto-sigmoid cancer (13/18, 72%) whereas a squamous cell carcinoma featured prominently in patients with urinary bladder cancer.

Pelvic exenteration with a urinary conduit was the most frequently performed operation (11 patients) in the group of patients with a malignant colovesical fistula. In the patients with recto-sigmoid cancers, an R0 resection could be achieved in nine patients whereas R1 and R2 resections were achieved in four and three patients, respectively. A higher number of R0 resections (7/11 [64%] vs. 2/4 [50%], P = 0.3) with pelvic exenteration was achieved compared with an anterior resection and Hartmann procedure with primary repair of the urinary bladder. Pelvic exenteration was also associated with a lower five-year mortality (41% vs. 50%, P = 1.0) in recto-sigmoid cancer. Involvement of the posterior wall of the urinary bladder was significantly higher in patients with a malignant colovesical fistula than in patients with a benign fistula (9/18 [50%] vs. 3/37 [9%], P = 0.004) and was associated with a higher urinary conduit rate (12/18 [68%] vs. 1/37 [4%]; P = 0.00).

DISCUSSION

Many studies have discussed the different aspects of colovesical fistulae [12, 13, 14]; however, no previous study has compared the management and the outcome of this condition on the basis of aetiology. A colovesical fistulae can be a complication of injury, inflammation and malignancy, all of which share a similar presentation. Conservative treatment and laparoscopic procedures have been suggested for the treatment of a colovesical fistula; however, these are applicable to selected cases only [15, 16, 17]. Open surgical procedures are still the mainstay of treatment for this condition. In this study, we divided these conditions into two major categories, benign and malignant, on the basis of similarities in management and outcome. Minor differences in individual pathologies existed; however, significant differences were observed only between these two broad categories.

No significant differences in age, gender, symptoms, preoperative risk and comorbidities, factors that could influence outcome, were observed between these two groups. The median age in the malignant group was slightly higher than it was in the benign group (68 years; IQR, 45-75 years vs. 64 years; IQR, 48-71 years), but this difference was not statistically significant. The patients with Crohn disease were slightly younger (47 years). Most patients were male, which can be explained by the close proximity of the urinary bladder to the bowel in male patients, as female reproductive organs have a protective role against this complication. The same findings have been described in previous studies [4, 5].

Urine examination, cystoscopy and colonoscopy/flexible sigmoidoscopy were performed in more than 80% of the patients. These investigations diagnosed the colovesical fistula in more than 60% of the patients in both groups. Colonoscopy was also performed for patients with malignancies to rule out synchronous lesions. A computed tomography (CT) scan was done primarily as an adjunct to rule out other abdominal pathologies. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was done more frequently in patients with malignancies than in patients without malignancies (50% vs. 5%) due to its primary importance in the staging of pelvic cancer whereas cystography was used more frequently used in the benign group than it was in the malignant group (38% vs. 6%) primarily because of the difficulty of diagnosis with other modalities. Garcea et al. [4] reported that endoscopy and barium enema could used for the successful diagnosis of with diverticular disease in up to 94% of patients; however, contrast enema was used only in 24% of patients in the present study. Najjar et al. [18] reported that CT scan, cystography and barium enema were superior to cystoscopy and colonoscopy in the diagnosis of colovesical fistulae.

Diverticular disease and Crohn disease are the two major causes of benign colovesical fistulae, as has been mentioned in a previous study [4]. Diverticular disease was the most common cause in all types of colovesical fistulae in the present study, as well as in previous studies [19, 20]. Benign colovesical fistulae involved the sigmoid colon more frequently (91%) than malignant fistulae did (55%) whereas malignant colovesical fistulae more frequently involved the rectum than benign colovesical fistulae did (45% vs. 9%, P = 0.009). Similarly, involvement of the posterior wall of the urinary bladder was significantly higher in patients with a malignant colovesical fistula than it was in patients with a benign colovesical fistula (50% vs. 9%, P = 0.004). Anterior resection, partial colectomy, and Hartmann procedure were done in the majority (87%) of patients with benign conditions with no recurrence of the fistula and no mortality within three months following the surgery.

Crohn disease was found to involve multiple intestinal loops with subsequent resections more frequently than rest of the conditions (60% vs. 6%), which can be explained by the involvements of multiple segments of the intestines by inflammatory processes. The Hartmann procedure was performed more frequently for patients with benign colovesical fistulae than for patients with malignant colovesical fistulae (22% vs. 6%) and was primarily performed on patients in emergency situations or with inflammatory conditions and to reduce the operative time in high-risk patients with an intention to reverse it at a later stage; however, the majority of patients (88%) could not have reversal either because of higher operative risk, patient preference to live with a stoma, or surgeon's preference not to reoperate due to previous complicated surgeries. A low rate of reversal of the Hartmann procedure has also been previously reported [21]. Early postoperative complications in patients with benign colovesical fistulae included wound infection (14%), anastomotic dehiscence (11%), pelvic collection (11%) and ileus (8%). The majority (90%) of leaks and collections were managed conservatively or with ultrasound or CT guided drainage. Only one patient needed a reoperation and covering ileostomy. Incisional and parastomal hernias were significantly higher in patients with benign colovesical fistulae, particularly for fistulae associated with diverticular disease, than they were in patients with malignant colovesical fistulae (30% vs. 6%). The likely cause for this could be collagen defects in patients of diverticular disease [22].

The present study reports the largest series of patients with malignant colovesical fistulae to date, with all the patients having been treated by a single surgeon. This was primarily because the center at which it was performed is a specialized tertiary care referral center for colorectal cancer. Before this study, Holmes et al. [5], in 1992, had reported the largest number of malignant colovesical fistulae. They reported pelvic exenteration in three cases (27%) only, with recurrence in three and mortality in two cases. Garcea et al. [4] reported 11 cases with cancers and only one exenteration, with similar results.

In the present series, 11 patients (67%) with cancers had a pelvic exenteration with permanent stoma. No patient had a recurrence of a fistula and there were no mortalities within three months of surgery; however, the five-year mortality due to all causes was significantly higher in patients with malignant colovesical fistulae than it was in patients with benign colovesical fistulae. In addition, in comparison to limited resections, pelvic exenteration had a higher (64% vs. 50%) rate of tumor-free margins (R0 resections) and a lower five-year mortality rate (41% vs. 50%, P = 1.0); however, these differences were not statistically significant, which was most likely due to the small sample size.

Patients with malignant colovesical fistulae had a significantly higher early postoperative complication rate as compared to those with benign colovesical fistulae (P = 0.0005). The major difference was in pelvic collection (39% vs. 11%), wound dehiscence (17% vs. 0%) and thrombo-embolism (17% vs. 0%). The higher rate of pelvic collection was likely due to preoperative chemo-radiotherapy and extensive resections, especially pelvic exenteration (46% vs. 29%); congruently, a malignant colovesical fistulae was associated with a higher incidence of thrombo-embolism and wound breakdown [23].

In conclusion, the present study has discussed the management of and the outcome for patients with colovesical fistulae in relation to aetiology. These results can help surgeons dealing with colovesical fistulae to develop appropriate management strategies based on aetiology. The findings of this study can also be helpful in the counseling and consent process to assist patients in making better decisions. The limitation of this study was the retrospective nature of the data. This study concluded that despite similar clinical presentation, the management of and the outcome for patients with colovesical fistulae varied significantly with the aetiology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are thankful to Miss Sabeena Malik for her contribution in preparing the manuscript.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Kellogg WA. Vesico-enteric fistula. Am J Surg. 1938;41:136. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cripps H. Passage of air and faeces from the urethra. Lancet. 1888;2:619. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao PN, Knox R, Barnard RJ, Schofield PF. Management of colovesical fistula. Br J Surg. 1987;74:362–363. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800740511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcea G, Majid I, Sutton CD, Pattenden CJ, Thomas WM. Diagnosis and management of colovesical fistulae; six-year experience of 90 consecutive cases. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:347–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holmes SA, Christmas TJ, Kirby RS, Hendry WF. Management of colovesical fistulae associated with pelvic malignancy. Br J Surg. 1992;79:432–434. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rieger N, Brundell S. Colovesical fistula secondary to laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal polypropylene (TAPP) mesh hernioplasty. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:218–219. doi: 10.1007/s004640041004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barreto SG, Schoemaker D, Siddins M, Wattchow D. Colovesical fistula following an open preperitoneal "Kugel" mesh repair of an inguinal hernia. Hernia. 2009;13:647–649. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0496-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan MS, Bryson C, O'Brien A, Mackle EJ. Colovesical fistula caused by chronic chicken bone perforation. Ir J Med Sci. 1996;165:51–52. doi: 10.1007/BF02942805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daoud F, Awwad ZM, Masad J. Colovesical fistula due to a lost gallstone following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2001;31:255–257. doi: 10.1007/s005950170181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abbas F, Memon A. Colovesical fistula: an unusual complication of prostatomegaly. J Urol. 1994;152(2 Pt 1):479–481. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32770-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cockell A, McQuillan T, Doyle TN, Reid DJ. Colovesical fistula caused by appendicitis. Br J Clin Pract. 1990;44:682–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tonolini M, Bianco R. Multidetector CT cystography for imaging colovesical fistulas and iatrogenic bladder leaks. Insights Imaging. 2012;3:181–187. doi: 10.1007/s13244-011-0145-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smeenk RM, Plaisier PW, van der Hoeven JA, Hesp WL. Outcome of surgery for colovesical and colovaginal fistulas of diverticular origin in 40 patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1559–1565. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1919-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker KG, Anderson JH, Iskander N, McKee RF, Finlay IG. Colonic resection for colovesical fistula: 5-year follow-up. Colorectal Dis. 2002;4:270–274. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2002.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solkar MH, Forshaw MJ, Sankararajah D, Stewart M, Parker MC. Colovesical fistula: is a surgical approach always justified? Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:467–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartus CM, Lipof T, Sarwar CM, Vignati PV, Johnson KH, Sardella WV, et al. Colovesical fistula: not a contraindication to elective laparoscopic colectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:233–236. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0849-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsivian A, Kyzer S, Shtricker A, Benjamin S, Sidi AA. Laparoscopic treatment of colovesical fistulas: technique and review of the literature. Int J Urol. 2006;13:664–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Najjar SF, Jamal MK, Savas JF, Miller TA. The spectrum of colovesical fistula and diagnostic paradigm. Am J Surg. 2004;188:617–621. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carvajal Balaguera J, Camunas Segovia J, Pena Gamarra L, Oliart Delgado de Torres S, Martin Garcia-Almenta M, Viso Ciudad S, et al. Colovesical fistula complicating diverticular disease: one-stage resection. Int Surg. 2006;91:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vasilevsky CA, Belliveau P, Trudel JL, Stein BL, Gordon PH. Fistulas complicating diverticulitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1998;13:57–60. doi: 10.1007/s003840050135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen PC, Lin SC, Lin BW, Lee JC. A comparison between Hartmann's procedure and primary anastomosis with defunctioning stoma in complicated left-sided colonic perforation. J Soc Colon Rectal Surgeon (Taiwan) 2012;23:13–18. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hobson KG, Roberts PL. Etiology and pathophysiology of diverticular disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2004;17:147–153. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-832695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Payne WG, Naidu DK, Wheeler CK, Barkoe D, Mentis M, Salas RE, et al. Wound healing in patients with cancer. Eplasty. 2008;8:e9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]