Abstract

Patient: Female, 73

Final Diagnosis: Drug induced acute hepatitis

Symptoms: Abdominal pain • diarrhea • vomiting

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Objective:

Unusual or unexpected effect of treatment

Background:

The use of herbal medications to treat various diseases is on the rise. Cinnamon has been reported to improve glycolated hemoglobin and serum glucose levels. When patients consider the benefit of such substances, they are often not aware of potential adverse effects and drug interactions. Cinnamon, via coumarin, can cause liver toxicity. Therefore, its concomitant use with hepatotoxic drugs should be avoided.

Case Report:

A 73-year-old woman was seen in the Emergency Department complaining of abdominal pain associated with vomiting and diarrhea after she started taking cinnamon supplements for about 1 week. The patient had been taking statin for coronary artery disease for many months. The laboratory workup and imaging studies confirmed the diagnosis of hepatitis. The detail workup did not reveal any specific cause. Cinnamon and statin were held. A few weeks after discharge, the statin was resumed without any further complications. This led to a diagnosis of cinnamon-statin combination-induced hepatitis.

Conclusions:

A combination of cinnamon supplement and statin can cause hepatitis, and it should be discouraged.

MeSH Keywords: Cinnamomum aromaticum, Hepatitis, Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA Reductase Inhibitors

Background

Diabetics often resort to herbal remedies as a ‘natural’ alternative to traditional medications in an effort to avoid adverse effects [1]. Definitive efficacy and safety data on herbal medicines for diabetes are lacking. Nevertheless, the use of such treatments is on the rise, and clinicians are advised to ask and educate patients about their potential adverse effects [2]. Cinnamon is considered to increase glucose uptake, glycogen synthesis, and phosphorylation of the insulin receptors [3]. It has been shown to improve glycolated hemoglobin levels. While these studies demonstrate the efficacy of cinnamon on diabetes, they did not describe adverse effects caused by it. One of the contents of cinnamon is coumarin, which has associated health risks [4]. A metabolite of coumarin could cause hepatotoxicity [5], and its concomitant use with other medications that have potential for liver damage should be discouraged. Herein, we report a case of acute hepatitis after the addition of cinnamon to a high-dose regimen of rosuvastatin.

Case Report

A 73-year-old woman was seen in the Emergency Department complaining of abdominal pain associated with vomiting and diarrhea after she started taking cinnamon supplements for about 1 week. The patient’s pain was epigastric, radiating into her right upper quadrant and also into her chest. It was reported to be worse with palpation and deep inspiration, and was quite different from her angina pain, which necessitated her to have 2 stents placed approximately 8 months before this admission. The patient denied having any hematemesis, melena, or hematochezia. The patient’s medical history included coronary artery disease with prior stent placement (8 months ago), hypertension, diabetes, depression, hyperlipidemia, gastroesophageal reflux, and chronic back pain. She also had a history of cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, and exploratory laparotomy for recurrent abdominal pain. She is a social alcohol drinker and current tobacco abuser. She was taking rosuvastatin 40 mg orally once a day for coronary artery disease. Her other medications included paroxetine, amlodipine, aspirin, clopidogrel, insulin, losartan, metoprolol, and pantoprazole. She had started taking a cinnamon supplement to treat her diabetes.

Physical examination revealed a blood pressure of 107/56 mm Hg, a heart rate of 74/min, a temperature of 99.1°F, respiratory rate of 18 breaths/min, and oxygen saturation of 95% on room air. Heart and lung examination results were essentially negative. Her abdomen was tender, with palpation more prominent in the epigastric region and right upper quadrant. She also had a positive Murphy’s sign, but no scleral icterus. There were no signs of trauma to the abdomen and no ecchymoses or rashes. A complete laboratory workup is outlined in Table 1, essentially consistent with acute hepatitis with cholestatic feature.

Table 1.

The complete laboratory workup at the time of admission and discharge.

| Laboratory Test | At Admission | At Discharge | Normal value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspartate transaminase (AST) | 927 units/L | 52 units/L | 10–35 units/L |

| Alanine transaminase (ALT) | 550 units/L | 148 units/L | 10–35 units/L |

| Total Bilirubin | 0.4 mg/dL | 0.4 mg/dL | 0.1–1.0 mg/dL |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | 245 units/L | 144 units/L | 35–129 units/L |

| Creatinine | 0.6 mg/dL | 0.6 mg/dL | 0.5–1.0 mg/dL |

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase | 181 units/L | – | 0–40 units/L |

| Albumin | 3.9 g/dL | 4.1 g/dL | 3.5–5.2 g/dL |

| INR | 1.1 | 1.1 | – |

| Hemoglobin | 12.8 g/dL | 13.1 g/dL | 12–16 g/dL |

| White blood cell count | 2.9 g/dL | 4.2 g/dL | 4.8–10.8 g/dL |

| Platelets | 158 K/mcl | 158 K/mcl | 150–400 K/mcl |

| Total Protein | 5.8 g/dL | 6.1 g/dL | 6.6–8.7 g/dL |

| Hepatitis A IgM Antibody | Negative | – | Negative |

| Hepatitis B surface Antigen | Negative | – | Negative |

| Hepatitis B surface Antibody | Negative | – | Negative |

| Hepatits B core IgM Antibody | Negative | – | Negative |

| Hepatitis C Antibody | Negative | – | Negative |

| ANA | Negative | – | Negative |

| Anti–mitochondrial antibody | Negative | – | Negative |

| Anti–smooth muscle antibody | Negative | – | Negative |

A CT scan of the abdomen showed mild biliary ductal dilatation greater than expected for post-cholecystectomy, but an obstructing mass or calculus was not identified. Abdominal ultrasound showed ductal dilation without obstructing mass or evidence of gross injury. A magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) showed ductal dilation suspicious for dilation after previous cholecystectomy without an obstructive mass or calculus.

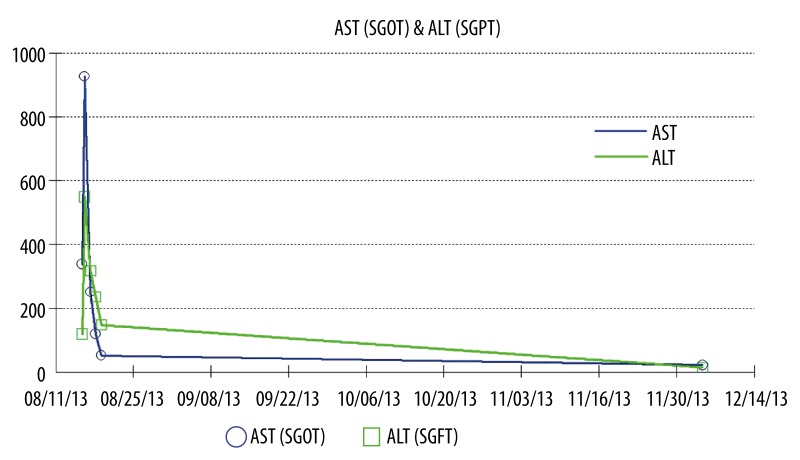

Rosuvastatin and the self-prescribed remedy of cinnamon were held. An endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was not performed because the patient had undergone drug-eluting stent placement approximately 8 months prior to admission and needed to continue dual antiplatelet therapy without interruption. As her hospital course progressed, her abdominal pain slowly resolved and she was discharged home. Since medication-induced hepatitis was higher in the differential diagnosis and the patient was on aspirin and clopidogrel, we decided to manage this patient conservatively. Therefore, liver biopsy was not performed. The statin therapy was restarted as an outpatient without resulting in elevated liver enzymes or abdominal pain (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

AST/ALT trends during the hospital course and outpatient follow up.

Discussion

The diagnosis of acute hepatitis covers a very broad spectrum of diagnoses. The common causes of significantly elevated liver enzymes are viral infection, toxins, and ischemia [6]. In our patient, an elevated level of alkaline phosphatase and marked elevation of GGT suggests hepatobiliary etiologies. The imaging studies essentially ruled out biliary causes. Negative hepatitis viral panel excludes the diagnosis of viral-induced hepatitis. There was no evidence of trauma or hemodynamic compromise that could precipitate ischemic or traumatic hepatitis. Other rare causes of significant elevation of liver enzymes such as Budd-Chiari syndrome and autoimmune hepatitis were ruled out via detailed workup. There were no other medications the patient was taking that could cause the extent of liver damage, except the cinnamon supplement. Table 2 contains lists of diagnosis that could cause significantly elevated liver enzymes (greater than 15 times upper normal limits) [7].

Table 2.

Etiology of significantly elevated AST/ALT (>15× upper normal limit).

| Acute viral hepatitis |

| Medications and toxins |

| Ischemic hepatitis |

| Autoimmune hepatitis |

| Wilson’s disease |

| Acute bile duct obstruction |

| Budd-Chiari syndrome |

| Hepatic artery ligation |

The combination of cinnamon supplementation and a high dose statin therapy was the likely etiology of the patient’s acute hepatitis. It is possible that the high-dose Rosuvastatin (40 mg) may be an obvious culprit, but this occurs in the early course of therapy [8]. Our patient had been taking rosuvastatin for months prior to the episode of acute hepatitis; therefore, it is unlikely the responsible agent. The overall risk of marked elevation of transaminases with statin is very small [9]. Several studies have reported that the coumarin in cinnamon is associated with acute liver damage [10,11]. Its concomitant use in patients taking statins is a concern [12]. While the exact mechanism of hepatotoxic effect is not known, o-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (o-HPAA), a metabolite of coumarin, was found to be hepatotoxic in animal studies [5]. Our patient had started taking cinnamon supplements along with a higher dose of rosuvastatin within a week of admission, and this combination may have caused an acute hepatitis-like syndrome with abdominal pain and significant liver enzyme elevation. This quickly resolved after the medications were held.

Naranjo et al. have devised a well-established algorithm to determine whether a medication is the cause of an adverse event or whether it is due to other confounding factors [13]. When applying the Naranjo algorithm to the patient in question, the adverse drug reaction would be considered probable for this patient (Table 3).

Table 3.

The Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction (ADR) Probability Scale for our patient.

| Questions | Yes | No | Do not know | Our patient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Are there previous conclusive reports on this reaction? | +1 | 0 | 0 | +1 |

| 2. Did the adverse event appear after the suspected drug was administered? | +2 | −1 | 0 | +2 |

| 3. Did the adverse reaction improve when the drug was discontinued or a specific antagonist was administered? | +1 | 0 | 0 | +1 |

| 4. Did the adverse reaction reappear when the drug was re-administered? | +2 | −1 | 0 | 0 |

| 5. Are there alternative causes (other than the drug) that could on their own have caused the reaction? | −1 | +2 | 0 | 0 |

| 6. Did the reaction reappear when a placebo was given? | −1 | +1 | 0 | 0 |

| 7. Was the drug detected in the blood (or other fluids) in concentrations known to be toxic? | +1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8. Was the reaction more severe when the dose was increased, or less severe when the dose was decreased? | +1 | 0 | 0 | +1 |

| 9. Did the patient have a similar reaction to the same or similar drugs in any previous exposure? | +1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10. Was the adverse event confirmed by any objective evidence? | +1 | 0 | 0 | +1 |

| Cumulative score | +6 |

Score of: 0=doubtful ADR, 1–4=possible ADR, 5–8=probable ADR, greater than 9=definitive

Conclusions

Patients with coronary artery disease often have other conditions such as diabetes, and their medication regimen includes statin therapy. Our case report shows that the combination of cinnamon and statins has the potential for significant liver damage. Therefore, patients should be warned against the use of these medications in combination.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None.

References:

- 1.Wang Z, Wang J, Chan P. Treating type 2 diabetes mellitus with traditional chinese and Indian medicinal herbs. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:343594. doi: 10.1155/2013/343594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeh GY, Eisenberg DM, Kaptchuk TJ, Phillips RS. Systematic Review of Herbs and Dietary Supplements for Glycemic Control in Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1277–94. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.4.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan A, Safdar M, Ali Khan MM, et al. Cinnamon Improves Glucose and Lipids of People With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3215–18. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.12.3215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ranasinghe P, Pigera S, Premakumara GA, et al. Medicinal properties of ‘true’ cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum): a systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13:275. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abraham K, Wohrlin F, Lindtner O, et al. Toxicology and risk assessment of coumarin: focus on human data. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2010;54:228–39. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aragon G, Younossi ZM. When and how to evaluate mildly elevated liver enzymes in apparently healthy patients. Clev Clinic J Med. 2010;77:195–204. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.77a.09064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green RM, Flamm S. AGA technical review on the evaluation of liver chemistry tests. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1367–84. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Famularo G, Miele L, Minisola G, Grieco A. Liver toxicity of rosuvastatin therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1286–88. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i8.1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kashani A, Phillips CO, Foody JM, et al. Risks associated with statin therapy: a systematic overview of randomized clinical trials. Circulation. 2006;114:2788–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.624890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell AP. Diabetes and Dietary Supplements. Clinical Diabetes. 2010;28:35–39. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen RW, Schwartzman E, Baker WL, et al. Cinnamon Use in Type 2 Diabetes: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:452–59. doi: 10.1370/afm.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ulbricht C, Seamon E, Windsor RC, et al. An evidence-based systematic review of cinnamon (Cinnamomum spp.) by the Natural Standard Research Collaboration. J Diet Suppl. 2011;8:378–454. doi: 10.3109/19390211.2011.627783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239–45. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]